Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

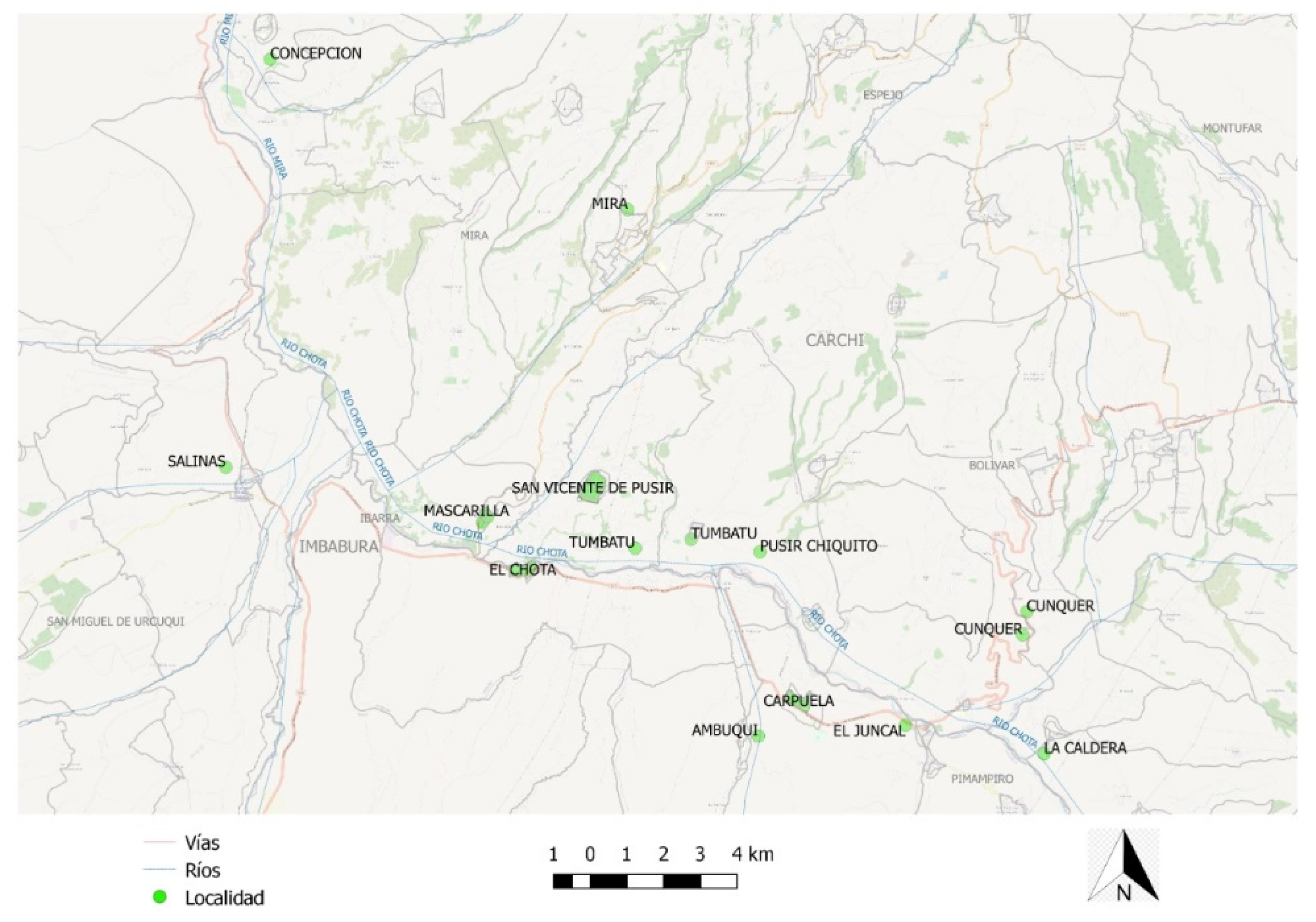

2. A look at the Chota Valley

3. Poverty and Climate Change

Poverty

- The dwelling has inadequate physical characteristics

- The house has inadequate services

- The household has high economic dependence

- In the home there are children who do not attend school

- The household is critically overcrowded

Climate Change and Poverty

“…changes in agricultural production models, derived from climate change, will affect food security in two ways. First, the food supply locally and globally will be affected. In many low-income countries, with limited financial capacity to trade and relying largely on their own production to meet their food needs, it may be impossible to make up for the decline in local supply without increasing their reliance on food aid. Second, all traditional forms of agricultural production will be affected and the ability to access food will be reduced.

It is important to mention that in addition to agricultural production, other processes of the food system are equally important with respect to food security and poverty, such as the processing, distribution, acquisition, preparation and consumption of food. With climate change, the risk of damage to transport by storms and distribution infrastructure increases with the consequent disorganization in food production chains. In addition to the above, current projections for 2030 show that the share of groceries in the average expenditure of a family will continue to increase, due, among other factors, to the growing scarcity of water, land and fuel that exert progressive pressure on food prices generating higher levels of poverty”.

- Methodology

- Quantitative Approach:

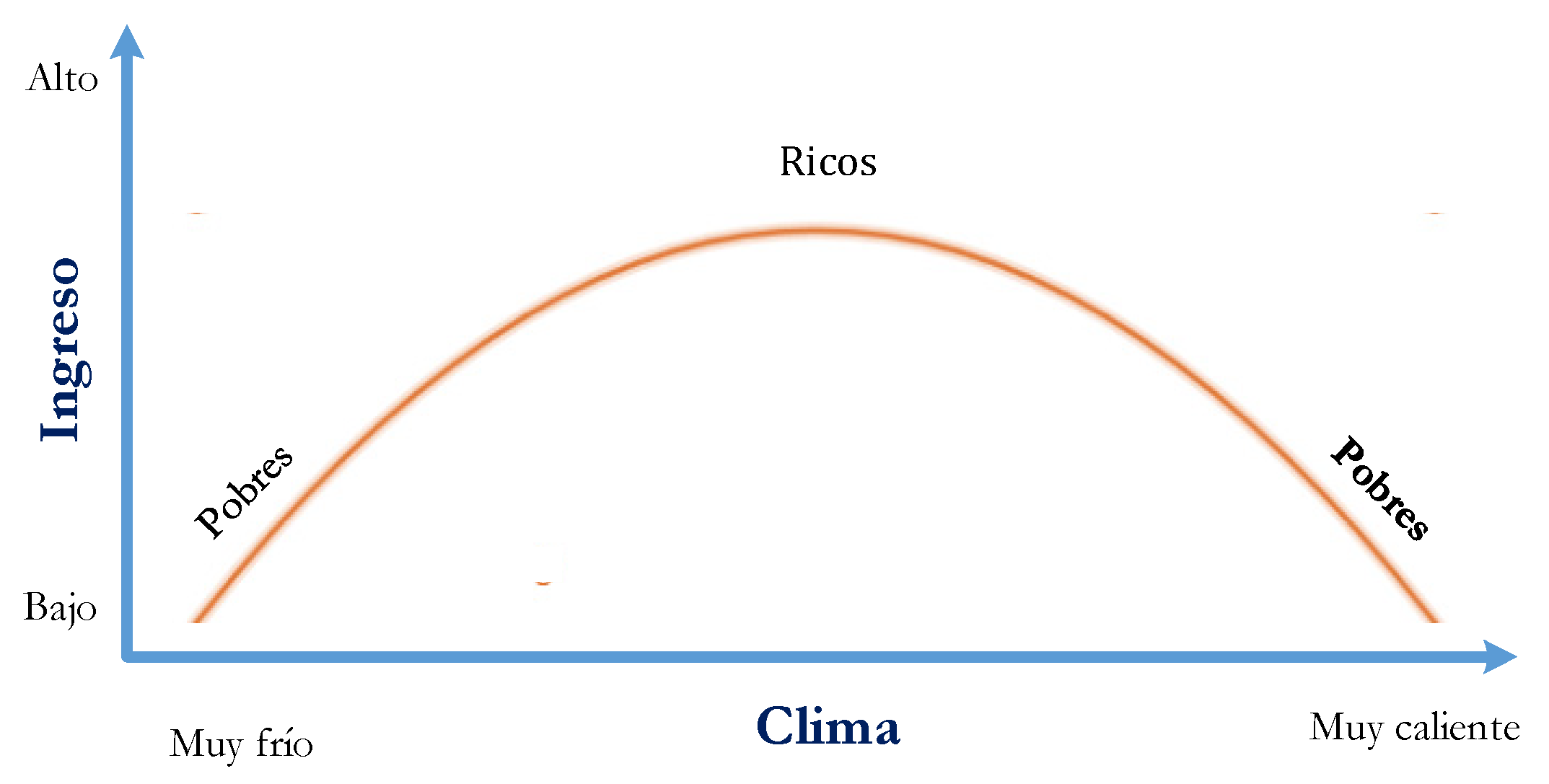

3.1. Relationship Between Poverty and Climatic Variables

- Household (agricultural) income per capita i

- Average temperature in the home location i

- Monthly average precipitation per quarter (taking the central month as a proxy for the quarter, that is, February, May, August, November)

- Home features vector i

- error term

3.2. Relationship Between Poverty, Knowledge About Climate Change, Actions and Adaptation to Climate Change

- is a binary dependent variable (with two possible values, 0 and 1).

- are a set of k independent variables, observed in order to predict or explain the value of .

- Y Knowledge about climate change

- Vector of independent variables, including the PMT variable

- Probability of knowing about climate change explained by the PMT poverty rate and household characteristics variables

- Regression coefficients (Parameters to be estimated)

Qualitative approach

4. Data

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Variables of the EVCH

- a.

- Housing and household variables

- b.

- Head of household variables

- c.

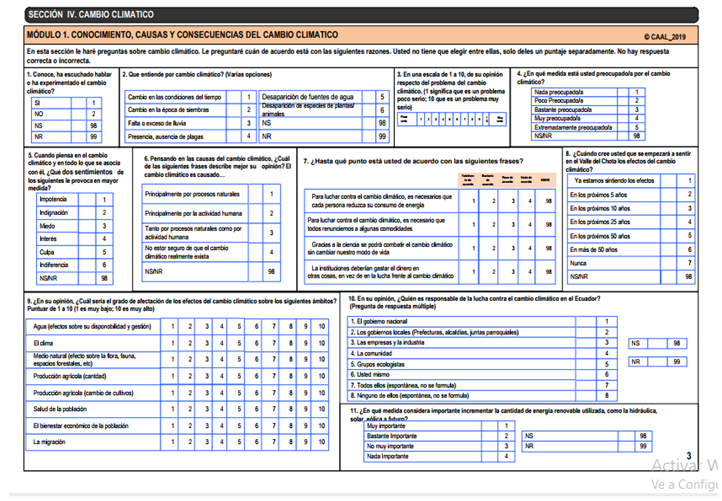

- Climate change variables

- c1. Knowledge, causes and consequences of climate change

- c2. Actions against climate change and adaptation measures

5.2. Poverty and Climatic Variables

- a.

- Variable selection

- - the average temperature in each location of data collection (taking the central month as a proxy for the quarter, that is, February, May, August and November)

- - the temperature of each locality squared

- - Monthly average precipitation per quarter (taking the central month as a proxy for the quarter, that is, February, May, August and November)

- - average monthly precipitation squared

- – Vector of household characteristics

- b.

- The regression model

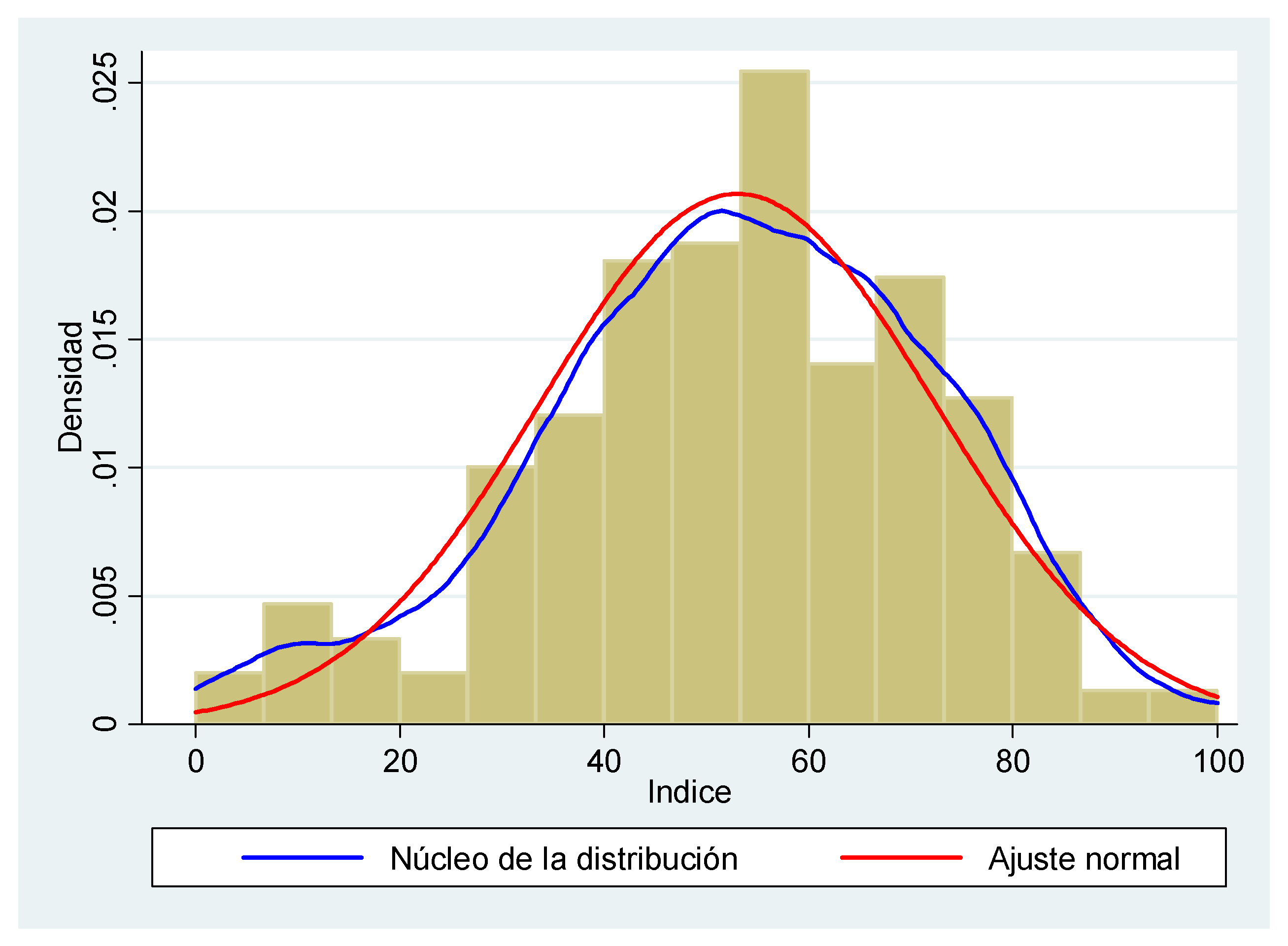

5.3. The Proxy Poverty Index

- a.

- Variable selection

- b.

- The PMT Index

5.4. Poverty and Knowledge About Climate Change

- a.

- Variable selection

- Where:

- PMT Proxy Poverty Index

- C1 Knows, has heard about or has experienced CC

- C2 What do you mean by CC: Change in weather conditions

- C3 What do you understand by CC: Change in the planting season

- C4 To fight CC it is necessary for each person to reduce energy consumption

- b.

- The regression model

5.5. Poverty and Actions Against Climate Change, Measures and Adaptation

- a.

- Variable selection

- Where:

- PMT Proxy Poverty Index

- A1 Agreement to develop and implement in the Chota Valley an adaptive model against CC (Saving water, garbage collection, less use of fungicides, etc.)

- A2 People believe that they could contribute to a greater extent to the fight against CC

- b.

- The regression model

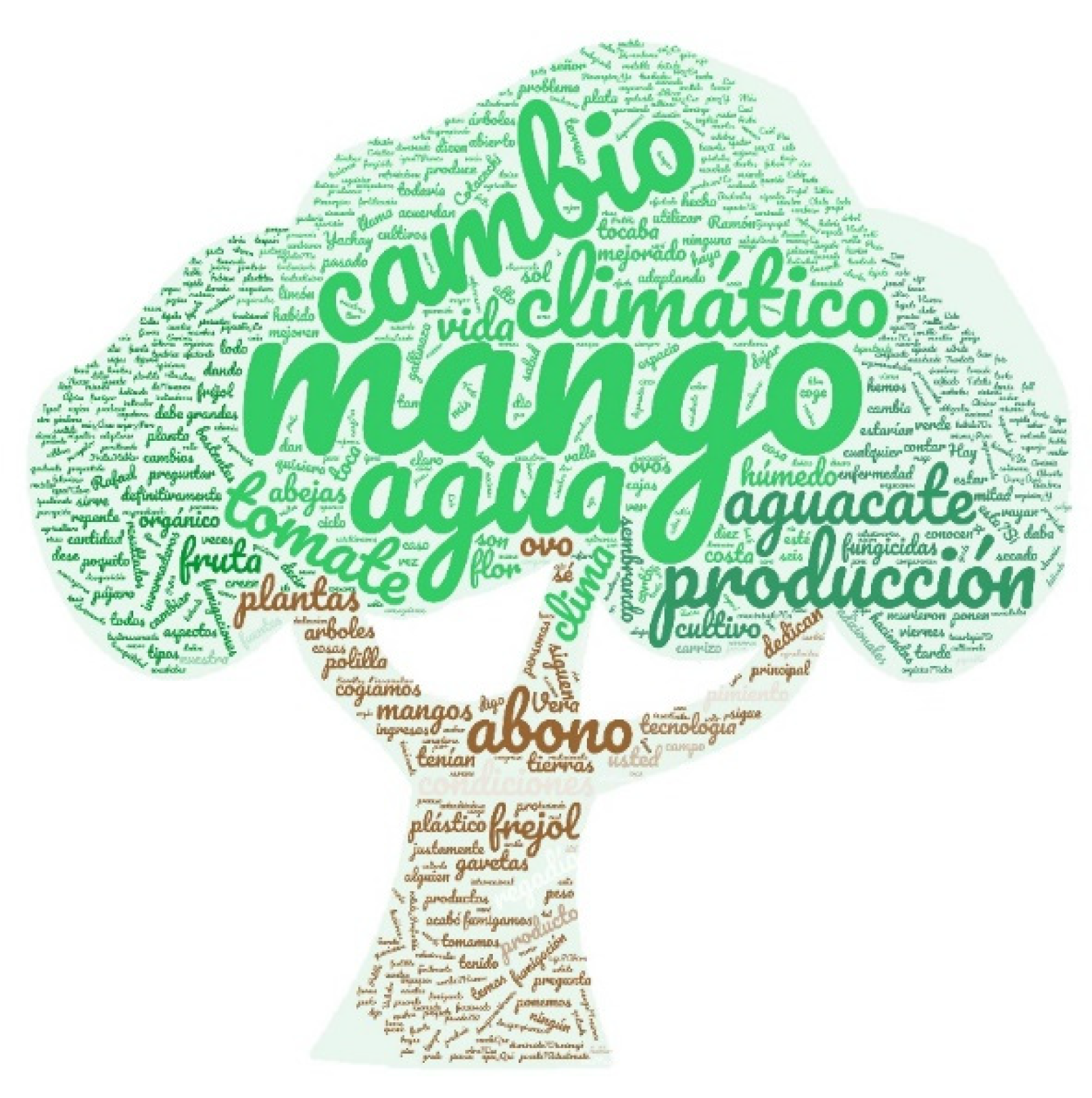

5.6. Focus Group

6. Conclusions

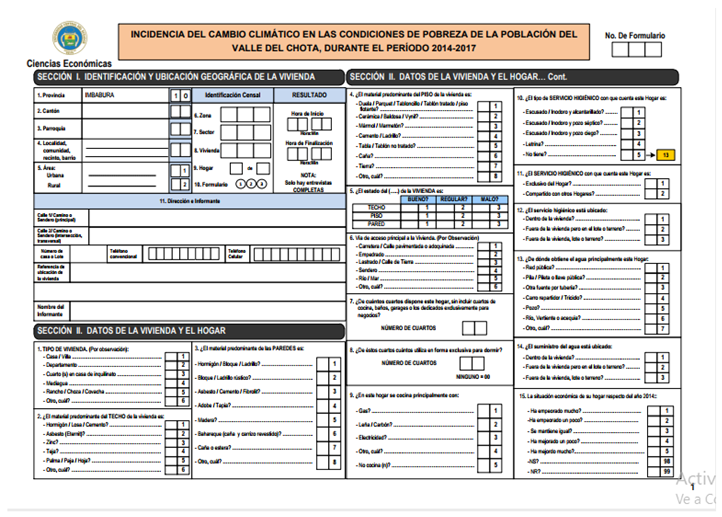

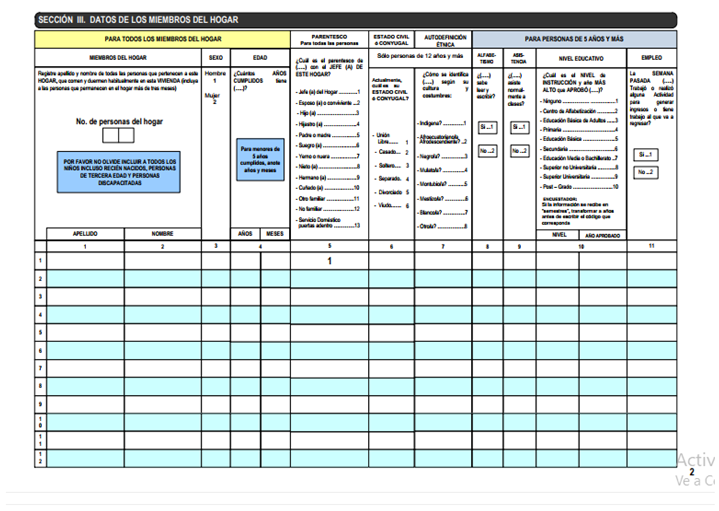

Appendix A

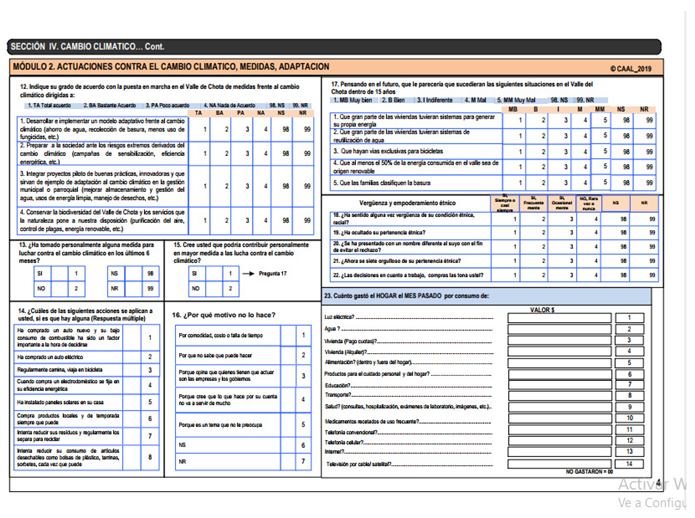

Appendix A.1. Form

|

|

|

|

Appendix A.2. Sample

- ⇨

- Sample quantitative part: 175 households (95% reliability, d=6% error). The calculation formula used is that of proportions with p=q=0.5

| POVERTY AND CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE CHOTA VALLEY | ||

| SAMPLE | ||

| Salinas | 14 | 14 |

| El Chota | 14 | 28 |

| Ambuquí | 14 | 42 |

| El Juncal | 14 | 14 |

| Chalguayacu | 14 | 14 |

| Caldera | 14 | 14 |

| Cuasquer | 14 | 14 |

| Carpuela | 14 | 28 |

| Pusir Chiquito | 14 | 14 |

| Tumbatú | 14 | 14 |

| San Vicente de Pusir | 14 | 14 |

| Mascarilla | 14 | 14 |

| TOTAL | 224 | |

- ⇨

- Sample qualitative part: Initially, the development of 2 focus groups of 10 people (Adults and youth represented equally by gender, authorities, leaders and local leaders, for each of the communities) is planned. Fewer or more focus groups may be held depending on the achievement of “component saturation”.

Appendix A.3. Guide to Questions

- Core Question

- How has climate change affected the poverty conditions of the population of Chota Valley, during the period 2014-2017?

- We are going to ask you to answer some questions about it:

- Big Topics:

- 1.

- Brief presentation of the topic and rules

- 2.

- Presentation of the participants

- 3.

-

Climate change knowledge

- 1-

- Have you heard or know about what climate change is?

- 2-

- From 2014 to now, have you seen changes in the local climate (I mean changes in rainfall, dry weather, hotter, colder)?

- 3-

- Regarding plants, have you seen or heard of the disappearance of some wild plants and the appearance of others?

- 4.

-

Opinion on changes in production

- 4-

- An indicator of climate change is said to be the presence or absence of bees. From your memories have you seen more bees before (2014) than now?

- 5-

- From 2014 to now, have you seen changes in the production of mangoes (I mean improvements, damage to the plants, have they had to apply more fungicides, do they no longer produce the same amount?

- 6-

- From 2014 to now, have you seen changes in the production of ovos (I mean improvements, damage to the plants, have they had to apply more fungicides, do they no longer produce the same amount?

- 7-

- From 2014 until now, have you seen changes in the production of tunas (I mean improvements, damage to the plants, have they had to apply more fungicides, do they no longer produce the same amount?

- 8-

- From 2014 to now, have you seen changes in the production of peppers (I mean improvements, damage to the plants, have they had to apply more fungicides, do they no longer produce the same amount?

- 5.

-

Opinion on water sources and irrigation

- 9-

- The sources of water for irrigation between 2014 and now remain the same (I mean that they all exist, their flow has been reduced, there were springs)

- 10-

- Regarding irrigation for the production of mangoes, if we compare between 2014 and now. Today it needs more irrigation, less irrigation or the same.

- 11-

- Regarding irrigation for the production of ovos, if we compare between 2014 and now. Today it needs more irrigation, less irrigation or the same.

- 12-

- Regarding irrigation for the production of tunas, if we compare between 2014 and now. Today it needs more irrigation, less irrigation or the same.

- 13-

- Regarding irrigation for the production of peppers, if we compare between 2014 and now. Today it needs more irrigation, less irrigation or the same.

- 6.

-

Perception of their standard of living

- 14-

- If you remember your standard of living in 2014, now it has improved, worsened or remains the same (understanding your standard of living as your income conditions, access to education, health, housing)

- 15-

- What is the main factor that has influenced the change in your standard of living?

- 16-

- Do you think that the change in your standard of living has to do with changes in climatic conditions (due to the change in production, in your health, etc...)

- 7.

-

Reaction to climate change

- 17-

- How you have been adapting to the effects of climate change in terms of yourself, the cultivation of your land

- 18-

- Knowing about the effects of climate change, you would be willing to take measures that are within your reach to counteract them (recycle garbage, do not waste so much water, do not use so much plastic...)

- 19-

- If there are stronger effects of climate change in the future, they are willing to react to them or they would stop farming.

- 8.

- Gratitude

Appendix A.4. Focus Group Transcript

References

- Accuweather. Accuweather. n.d. Available online: https://www.accuweather.com/.

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Recuento y medición multidimensional de la pobreza. Documento de Trabajo OPHI No. 7 2008, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.; Verner, D. Word Bank, Ed.; Simulating the Effects of Climate Change on Poverty and Inequality. In Reducing Poverty, Protecting Livelihoods, and Building Assets in a Changing Climate Social Implications of Climate Change for Latin America and the Caribbean; 2010; pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Boltvinik, J. Peter Townsend y el rumbo de la investigación sobre pobreza en Gran Bretaña, 2011.

- Booth, C. LIFE AND LABOUR OF THE PEOPLE IN LONDON.

- Bourguignon, F.; Chakravarty, S. Inequality, Polarization and Poverty. Inequality, Polarization and Poverty 2008, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPAL. Medidas de mitigación y adaptación al cambio climático en América Latina y el Caribe. CEPAL. 2017.

- Coronel, R. El Valle Sangriento 1580-1700: De los señoríos de la coca y el algodón a la cañera jesuita, 1987.

- Feres, J. C.; Mancero, X. Enofoque para la medición de la pobreza. Breve revisión de la literatura. In Estudios estadísticos y prospectivos. 2001. Available online: http://www.cepal.org/publicaciones/xml/8/14038/lc2024e.pdf.

- Freemeteo.org. Freemeteo.org freemeteo.org. n.d.

- García, A.; Responsable, G.; Barbero, C.; Técnica, S.; Educación, D. Cambio climático y Pobreza: Retos y Falsos Remedios, 2010.

- González, M.; Burguete, A.; Ortiz-t, P. La autonomía a debate Autogobierno indígena y Estado plurinacional en América Latina; S., E., FLACSO, Eds.; flacso, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, F. Población indígena y afroecuatoriana en Ecuador: diagnóstico sociodemográfico a partir del censo de 2001. Santiago: BID/Cepal 2005, 1–13. Available online: http://www.cepal.org/id.asp?id=22276.

- Hanna, R.; Schneider, J.; Hanna, R.; Hoffmann, B.; Oliva, P.; Schneider, J. The Power of Perception Limitations of Information in Reducing Air Pollution Exposure The Power of Perception Limitations of Information in Reducing Air Pollution Exposure. IDB Publications (Working Papers), 2021.

- IBM. Análisis de componentes principales categórico (CATPCA). SPSS Manual. 2015. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjjze--wZ_wAhUsmeAKHWLXDjwQFjAAegQIAhAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ibm.com%2Fdocs%2Fes%2FSSLVMB_subs%2Fstatistics_mainhelp_ddita%2Fspss%2Fcategories%2Fidh_cpca.html&usg=AOv.

- López-Feldman, A. Cambio climático, distribución del ingreso y la pobreza. El caso de México. Comisión Económica Para América Latina y El Caribe (CEPAL 2014, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J.; Fernández, A. Cambio climático: una visión desde México. In SEMARNAT. 2005. wars_12December2010.pdf%0Ahttps://think-asia.org/handle/11540/8282%0Ahttps://www.jstor.org/stable/41857625. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269107473_What_is_governance/link/548173090cf22525dcb61443/download%0Ahttp://www.econ.upf.edu/~reynal/Civil.

- Mendelsohn, R.; Arellano-Gonzalez, J.; Christensen, P. A Ricardian analysis of Mexican farms. Environment and Development Economics 2010, 15(2), 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mideksa, T. K. Economic and distributional impacts of climate change: The case of Ethiopia. Global Environmental Change 2010, 20(2), 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUD. Informe sobre desarrollo humano 1997. In Revista de Fomento Social 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUD. Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano años 2007-2008. 2007. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org.

- Sánchez, A.; Gay, C.; Estrada, F. Cambio climático y pobreza en el Distrito Federal. Investigacion Economica 2011, 70(278), 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, T. Some Economics of Global Warming. American Economic Association 1992, 80(1), 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Desarrollo y Libertad, 2011.

- Sirvent, M.; Rigal, L. Investigación Acción Participativa; Flacsoandes, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. AN INQUIRY INTO THE NATURE AND CAUSES OF THE WEALTH OF by.

- Spicker, P.; Álvarez, S.; Gordon, D. Pobreza Un glosario internacional. 2009. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/ar/libros/clacso/crop/glosario/glosario.pdf.

- Tsui, K. Y. Social Choice and Welfare. In Social Choice and Welfare; Number 1-SpringerLink, 2002; Volume 19, pp. 69–93. Available online: http://www.springerlink.com/index/9XJGK6DD7DFWMLW9.pdf.

- UNICEF. Diagnóstico de la situación. Niñas, niñas y adolescentes de Ecuador frente al cambio climático, 2020.

| Sociocultural Area (*) | Afro-Ecuadorian population | Total population | Percentages | |||

| 2001 | 2010 | 2001 | 2010 | 2001 | 2010 | |

| North Coast | 183,113 | 251,562 | 1,571,248 | 1,802,814 | 11.7% | 14.0% |

| Chota Valley | 24,783 | 26,262 | 496,983 | 546,535 | 5.0% | 4.8% |

| Pichincha | 78,621 | 128,327 | 2,388,817 | 2,745,575 | 3.3% | 4.7% |

| North Amazon | 10,884 | 14,631 | 294,627 | 398,799 | 3.7% | 3.7% |

| Central-South Coast | 275,452 | 428,210 | 4,889,810 | 5,286,021 | 5.6% | 8.1% |

| Center-South Sierra | 23,700 | 39,997 | 2,170,103 | 2,401,944 | 1.1% | 1.7% |

| Rest of the country | 7,456 | 7,172 | 345,020 | 366,074 | 2.2% | 2.0% |

| Total | 604,009 | 896,161 | 12,156,608 | 13,547,762 | ||

| Type of Housing | House/Villa | 62.5% |

| Mediagua | 33.5% | |

| Apartment/Room in each tenancy/Ranch-Shack-Covacha | 4.0% | |

| House Roof | Concrete/Slab/Cement | 40.2% |

| Zinc | 42.0% | |

| Asbestos/Eternit | 11.6% | |

| Tile/Other | 6.2% | |

| House Walls | Concrete/Block/Brick | 64.7% |

| Rustic Block/Brick | 29.5% | |

| Adobe/Wood | 5.8% | |

| Apartment Floor | Cement/Brick | 46.4% |

| Ceramic/Tile/Vynil | 36.2% | |

| Stave/Parquet/Plank/Floating Floor | 12.9% | |

| Board/Untreated Plank/Cane/Dirt | 4.5% | |

| State of the Roof of the House | Okay | 54.0% |

| Regular | 41.1% | |

| Bad | 4.9% | |

| Condition of the Walls of the House | Okay | 52.7% |

| Regular | 40.6% | |

| Bad | 6.7% | |

| State of the Apartment Floor | Okay | 53.6% |

| Regular | 42.4% | |

| Bad | 4.0% | |

| Access to Housing | Paved or Paved Road/Street | 89.3% |

| Cobbled / Ballasted / Dirt Road / Path | 10.7% | |

| Cooking Fuel | Gas | 97.8% |

| Wood/Coal/Electricity/No cooking | 2.2% | |

| Excreta Disposal Type | Toilet/Toilet and Sewer | 98.2% |

| Toilet / Toilet and Septic Tank / Does not have | 1.8% | |

| Type of Toilet Service | Home exclusive | 89.7% |

| Shared with others | 10.3% | |

| Location of the Toilet | Inside the house | 80.7% |

| Outside the house | 19.3% | |

| Water Source | Public network | 98.2% |

| Other source by pipeline/River slope or ditch | 1.8% | |

| Water Source Location | Inside the house | 79.9% |

| Outside the house | 20.1% | |

| Economic Situation of the Household compared to 2014 | It's gotten a lot worse/It's gotten a little worse | 82.1% |

| It remains the same | 12.5% | |

| It has improved a little/It has improved a lot | 5.4% |

| Sex | Men | 58.04% |

| Woman | 41.96% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 37.50% |

| Single | 19.20% | |

| Widower | 16.96% | |

| Free Union | 14.29% | |

| Separate | 7.59% | |

| Divorced | 4.46% | |

| Ethnic Self-Definition | Afro-Ecuadorian/Black/Mulatto | 73.22% |

| Half Blood | 25.00% | |

| Montubio | 0.89% | |

| Indigenous | 0.45% | |

| White | 0.45% | |

| Knows how to Read and Write | Yes | 86.16% |

| No | 13.84% | |

| Level of Instruction | Primary | 66.52% |

| None | 15.63% | |

| Middle school or high school | 7.14% | |

| Secondary | 6.25% | |

| University superior | 2.23% | |

| Basic education | 1.34% | |

| Basic ed. for adults | 0.45% | |

| Non-university higher | 0.45% | |

| Years of schooling of the person for the population aged 15 or over | 0 | 15.63% |

| 1 to 5 | 26.34% | |

| 6 | 41.07% | |

| 7 and over | 16.96% | |

| Employment | Yes | 76.79% |

| No | 23.21% |

| Variable | Obs. | Half | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

| Household Size | 224 | 3,027 | 1,599 | 1 | 8 |

| Head of Household Age | 224 | 53,295 | 16,564 | 18 | 92 |

| Head's Schooling | 224 | 5,366 | 3,795 | 0 | 17 |

| People in the Household with High School | 224 | 0.830 | 1,163 | 0 | 5 |

| Have you heard of climate change? | Yes | 93.3% |

| No | 6.3% | |

| NS | 0.4% | |

| According to you what is climate change? (Not exclusive) | Change in weather conditions | 78.1% |

| Change in planting season | 37.1% | |

| Lack or excess of rain | 23.7% | |

| Presence, absence of pests | 18.8% | |

| Disappearance of water sources | 14.7% | |

| Disappearance of plant/animal species | 11.2% | |

| On a scale of 1 to 10, your opinion regarding the problem of climate change. (1 means that it is not a serious problem; 10 means that it is a very serious problem) | From 1 to 5 | 19.6% |

| From 6 to 9 | 51.8% | |

| 10 | 28.6% | |

| How concerned are you about climate change? | Nothing/Little | 31.7% |

| Quite/Very/Extremely | 63.8% | |

| NS/NR | 4.5% | |

| How does climate change make you feel? | Impotence | 20.5% |

| Indignation | 31.3% | |

| Fear | 23.7% | |

| Interest | 7.1% | |

| Fault | 1.3% | |

| Indifference | 10.7% | |

| NS/NR | 5.4% | |

| Thinking about the causes of climate change, which of the following sentences best describes your opinion? Climate change is caused... | Mainly by natural processes | 30.4% |

| Mainly due to human activity | 27.2% | |

| Both by natural processes and by human activity | 33.0% | |

| I'm not sure climate change really exists | 4.0% | |

| NS/NR | 5.4% | |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements: (options totally agree + quite agree) Non-exclusive responses |

To fight climate change, it is necessary for each person to reduce their energy consumption | 58% |

| To fight climate change, we all need to give up some comforts | 58.9% | |

| Thanks to science, it will be possible to combat climate change without changing our way of life | 53.1% | |

| Institutions should spend the money on other things, instead of in the fight against climate change |

60.7% | |

| When do you think the effects of climate change will begin to be felt in the Chota Valley? | We are already feeling the effects | 85.7% |

| Between 5 and more than 50 years | 5.8% | |

| Never | 3.6% | |

| NS/NR | 4.9% | |

| What would be the degree of affectation of the effects of climate change on the following areas? Score from 1 to 10 (1 is very low; 10 is very high) (Options 6 to 10) Non-exclusive responses |

Water (effects on its availability and management) | 52.2% |

| The weather | 57.1% | |

| Natural environment (effect on flora, fauna, forest areas, etc.) | 61.6% | |

| Agricultural production (quantity) | 66.1% | |

| Agricultural production (change of crops) | 66.5% | |

| Population health | 58.9% | |

| The economic well-being of the population | 54.9% | |

| The migration | 32.1% |

| Who is responsible for the fight against climate change in Ecuador |

National government | 45.1% |

| Local Governments/Business and Industry/The Community/Environmental Groups/Yourself | 14.3% | |

| All of them | 33.9% | |

| None/NS/NR | 6.7% | |

| To what extent do you consider it important to increase the amount of renewable energy used, such as hydro, solar, wind in the future |

Very important/Fairly important | 84.8% |

| Not very important | 7.1% | |

| Nothing important/NS | 8.0% | |

| Indicate your degree of agreement with the implementation in the Chota Valley of measures against climate change aimed at: (Options total agreement + quite a lot of agreement) |

Develop and implement an adaptive model in the face of climate change (saving water, garbage collection, less use of fungicides, etc.) | 83.1% |

| Prepare society for the extreme risks arising from climate change (awareness campaigns, energy efficiency, etc.) | 82.6% | |

| Integrate pilot projects of good practices, innovative and that serve as an example of adaptation to climate change in municipal or parish management (improve storage and management of water, uses of clean energy, waste management, etc.) | 83% | |

| Conserve the biodiversity of the Chota Valley and the services that nature makes available to us (air purification, pest control, renewable energy, etc.) | 82.6% | |

| Have you personally taken any action to combat climate change in the last 6 months? | Yes | 69.2% |

| No | 25.4% | |

| NS | 5.4% | |

| Which of the following actions apply to you, if any (Not exclusive answers) |

Regularly walks, rides a bike | 68.3% |

| Try to reduce your consumption of disposable items such as plastic bags, tubs, straws, whenever you can | 26.3% | |

| Try to reduce your waste and regularly separate it for recycling | 23.7% | |

| Do you think you could personally contribute more to the fight against climate change? | Yes | 65.6% |

| No | 34.4% | |

| Why don't you do it? | For comfort | 6.3% |

| Because they don’t know what to do | 27.2% | |

| Because those who have to act are companies and governments | 0.4% | |

| NS | 0.4% | |

| Thinking about the future, what would you think if the following situations happened in the Chota Valley in 15 years? (Answers not exclusive) |

That a large part of the houses had systems to generate their own energy | 80.4% |

| That a large part of the houses has water reuse systems | 84.4% | |

| That there are exclusive bicycle lanes | 81.7% | |

| That at least 50% of the energy consumed in the valley be of renewable origin | 82.1% | |

| Let families sort the trash | 86.6% |

| Variable | Half | Typical deviation |

| First trimester temperature (°C) | 26.13 | .30 |

| Second trimester temperature (°C) | 25.99 | .22 |

| Third trimester temperature (°C) | 25.40 | .25 |

| Fourth trimester temperature (°C) | 26.43 | .25 |

| First quarter rainfall (mm/month) | 175.98 | .25 |

| Second quarter rainfall (mm/month) | 171.09 | .47 |

| Third Quarter Precipitation (mm/month) | 110.24 | 6.04 |

| Fourth Quarter Precipitation (mm/month) | 189.73 | .97 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| Coefficient | Est. t | Coefficient | Est. t | Coefficient | Est. t | |

| First trimester temperature squared | -0.00034 | -0.134 | 0.00418 | 1.026 | 0.00343 | 0.850 |

| Second quarter temperature | 51.68860 | 1.824 | 81.77212 | 1.627 | ||

| Second quarter temperature squared | -1.00478 | -1.807 | -1.58593 | -1.608 | -0.42233 | -1.159 |

| Third trimester temperature | -20.82325* | -1.994 | -30.55873 | -1.978 | ||

| Third quarter temperature squared | 0.42512* | 1.979 | 0.61855 | 1.955 | 0.02271 | 1.413 |

| Fourth quarter temperature squared | 0.01389* | 2.464 | .02418** | 2.875 | -2.02820* | -2.255 |

| First quarter precipitation squared | -0.02516 | -0.362 | -0.00452 | -0.043 | 0.00320 | 0.029 |

| Second Quarter Precipitation Squared | 0.00259 | 0.149 | 0.02338 | 0.723 | -0.90740 | -1.185 |

| Third quarter precipitation | -2.94455 | -1.814 | -6.76236** | -2.687 | ||

| Third Quarter Precipitation Squared | 0.13142 | 1.786 | 0.30525** | 2.661 | 0.12315 | 1.237 |

| Fourth Quarter Precipitation Squared | 0.03029* | 2.225 | 0.03769 | 1.959 | -4.30757* | -2.261 |

| Years of schooling | 0.09591 | 1.956 | 0.09591 | 1.956 | ||

| Experience | -0.00334 | -1.120 | -0.00334 | -1.120 | ||

| Gender1 (1=Male) | 0.04718 | 0.320 | 0.04718 | 0.320 | ||

| Ethnicity1 (1=Afro-Ecuadorian) | -0.12947 | -0.807 | -0.12947 | -0.807 | ||

| Ethnicity3 (1=Other) | -0.18041 | -0.506 | -0.18041 | -0.506 | ||

| People with high school in the home | -0.10905 | -1.786 | -0.10905 | -1.786 | ||

| Temperature*Precipitation second quarter | 1.22594 | 1.159 | ||||

| Temperature*Precipitation third quarter | -0.10909 | -1.221 | ||||

| Temperature*Precipitation fourth quarter | 5.97558* | 2.264 | ||||

| Constant | -403.44520 | -1.484 | -676.13010 | -1.342 | -26.82548 | -0.571 |

| R-squared | 0.08540 | 0.27499 | 0.27499 | |||

| Cases | 224 | |||||

| * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 Source: EVCH. Own elaboration |

||||||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| dy/dx | z | dy/dx | z | dy/dx | z | |

| First trimester temperature squared | -0.00034 | -0.13 | 0.00418 | 1.03 | 0.00343 | 0.85 |

| Second quarter temperature | 51.68860 | 1.82 | 81.77213 | 1.63 | ||

| Second quarter temperature squared | -1.00478 | -1.81 | -1.58593 | -1.61 | -0.42233 | -1.16 |

| Third trimester temperature | -20.82325 | -1.99 | -30.55874 | -1.98 | ||

| Third quarter temperature squared | 0.42512 | 1.98 | 0.61855 | 1.96 | 0.02271 | 1.41 |

| Fourth quarter temperature squared | 0.01389 | 2.46 | 0.02418 | 2.88 | -2.02820 | -2.25 |

| First quarter precipitation squared | -0.02516 | -0.36 | -0.00452 | -0.04 | 0.00320 | 0.03 |

| Second quarter precipitation squared | 0.00259 | 0.15 | 0.02338 | 0.72 | -0.90740 | -1.18 |

| Third quarter precipitation | -2.94455 | -1.81 | -6.76236 | -2.69 | ||

| Third quarter precipitation squared | 0.13142 | 1.79 | 0.30524 | 2.66 | 0.12315 | 1.24 |

| Fourth quarter precipitation squared | 0.03029 | 2.23 | 0.03769 | 1.96 | -4.30757 | -2.26 |

| Years of schooling | 0.09591 | 1.96 | 0.09591 | 1.96 | ||

| Experience | -0.00334 | -1.12 | -0.00334 | -1.12 | ||

| Gender1 (1=Male) | 0.04718 | 0.32 | 0.04718 | 0.32 | ||

| Ethnicity1 (1=Afro-Ecuadorian) | -0.12947 | -0.81 | -0.12947 | -0.81 | ||

| Ethnicity3 (1=Other) | -0.18041 | -0.51 | -0.18041 | -0.51 | ||

| People with high school in the home | -0.10905 | -1.79 | -0.10905 | -1.79 | ||

| Temperature*Precipitation second quarter | 1.22594 | 1.16 | ||||

| Temperature*Precipitation third quarter | -0.10909 | -1.22 | ||||

| Temperature*Precipitation fourth quarter | 5.97559 | 2.26 | ||||

| Variable | Categories |

| Predominant material on the FLOOR | 1 Untreated Board/Plank-Cane-Soil-Other, which one |

| 2 Cement/Brick | |

| 3 Stave/Parquet/Plank/Floating floor-Ceramic/Tile/Vynil-Marble | |

| Location of the BATHROOM | 1 Outside the home but on the lot- Outside the home, lot or land |

| 2 Inside the house | |

| Main material of the CEILING | 1 Zinc/Palm/Straw/Leaf-Other, which one |

| 2 Asbestos/Tile | |

| 3 Concrete/Slab/Cement | |

| State of the FLOOR of the house | 1 Bad |

| 2 Fair | |

| 3 Good | |

| WATER supply location | 1 Outside the home but on the lot- Outside the home, lot or land |

| 2 Inside the house | |

| ROAD of access to the house | 1 Path- River/Sea -Other |

| 2 Cobbled - Ballast/Soil street | |

| Road/Street paved or cobblestone | |

| BATHROOM Type | 1 Latrine-Does not have |

| 2 Toilet / Toilet and cesspool | |

| 3 Toilet / Toilet and septic tank | |

| 4 Toilet/Toilet and sewer | |

| Main source of household WATER | 1 Delivery car/Tricycle-Well/River, spring or ditch-Other, which one |

| 2 Other source by pipeline | |

| 3 Public network- Battery/pool or public key | |

| Predominant material of the WALLS | 1 Adobe/Tapia-Wood-Bahareque-Cane or mat-Other, which one |

| 2 Block/Rustic brick- Asbestos/Cement/Fibrolit | |

| 3 Concrete/Block/Brick | |

| HOUSING type | 1 Room in a tenancy house-Mediagua-Ranch/Shack/Covacha-Other, which one |

| 2 House/Villa-Apartment |

| Variable | Categories |

| Number of illiterate people in the household | 1 One or more |

| 2 There are no illiterate people | |

| Years of schooling of the household head | 1 Up to 6 years |

| 2 Between 7 and 12 years | |

| 3 13 years and over | |

| 4 Under 5 years | |

| Number of people from 5 to 17 years old in the household who do not attend to school | 1 One or more |

| 2 No children 5-17/Everyone attends | |

| Number of people aged 5 to 17 employed | 1 One or more |

| 2 There are no children between the ages of 5 and 17 employed | |

| Children under 6 years old in the household | 1 Two or more |

| 2 One | |

| 3 There are no children in that age | |

| Number of people aged 65 and over in the household | 1 Two or more |

| 2 One | |

| 3 There are no older adults |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Household Characteristics Index | 224 | 69.19 | 15.32 | 0 | 100 |

| People Index | 224 | 38.04 | 18.29 | 0 | 100 |

| PMT Index | 224 | 53.05 | 19.30 | 0 | 100 |

| Know, have heard of or have experienced CC | 1 Yes |

| 0 No, don't know | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Change in weather conditions |

| 0 Other | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Change in planting time |

| 0 Other | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Lack or excess of rain |

| 0 Other | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Presence, absence of pests |

| 0 Other | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Disappearance of water sources |

| 0 Other | |

| What do you mean by CC? | 1 Disappearance of species |

| 0 Other | |

| CC is a problem | 1 Very serious |

| 0 Nothing serious | |

| To what extent are you concerned about CC | 1 Concerned, very concerned about CC |

| 0 Little or not at all worried about CC | |

| When talking about CC, what feelings does it provoke? | 1 Helplessness, indignation, fear, interest, guilt |

| 0 Indifference | |

| Climate change is caused by | 1 Natural processes, human activity |

| 0 Does not exist | |

| How far is it | 1 Agree to reduce energy consumption |

| 0 I do not agree to reduce energy consumption | |

| How far is it | 1 Agree to give up comforts |

| 0 I do not agree to give up comforts | |

| How far is it | 1 Agree that science will help fight CC. |

| 0 I do not agree that science will help fight CC. | |

| To what extent do you think | 1 Institutions must spend in the fight against CC |

| 0 Institutions should NOT spend in the fight against CC | |

| When do you think the effects of CC will begin to be felt? | 1 Short-term effects |

| 0 Long-term effects or never | |

| What is the degree of affectation on the water | 1 High impact of CC on water |

| 0 Low affectation of the CC on the water | |

| What is the degree of impact on the weather | 1 High impact of CC on weather |

| 0 Low impact of the CC on the weather | |

| What is the degree of impact on the natural environment | 1 High impact of the CC on the natural environment |

| 0 Low impact of the CC on the natural environment | |

| What is the degree of affectation on agricultural production (quantity) | 1 High impact of CC on the amount of agricultural production |

| 0 Low impact of CC on the amount of agricultural production | |

| What is the degree of affectation on agricultural production (change of crops) | 1 High impact on CC that drives crop change |

| 0 Low impact on CC that drives crop change | |

| What is the degree of affectation on the health of the population | 1 High impact of CC on health |

| 0 Low effect of CC on health | |

| What is the degree of impact on the economy | 1 High impact of CC on the economy |

| 0 Low impact of the CC on the economy | |

| What is the degree of affectation on migration | 1 High impact of CC on migration |

| 0 Low impact of CC on migration | |

| Who should fight CC | 1 Who must fight against CC is the government, the company |

| 2 Those who must fight against CC are the people | |

| 3 Everyone Must Fight against CC | |

| Considers it important to increase the amount of renewable energy | 1 Important to increase renewable energy |

| 0 Little or not at all important to increase renewable energy |

| PMT | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| PMT | 1 | ||||

| C1 | 0.1318 | 1 | |||

| C2 | 0.157 | 0.3767 | 1 | ||

| C3 | 0.1755 | 0.1686 | 0.406 | 1 | |

| C4 | -0.1272 | 0.3501 | 0.1587 | -0.1134 | 1 |

| Logistic regression | Number of obs | = | 224 | |||

| LR chi 2 (3) | = | 13.06 | ||||

| prob > chi2 | = | 0.0045 | ||||

| Loglikelihood = -58.412319 | Pseudo -R2 | = | 0.1006 | |||

| Change in planting season | Coef. | Std. Err. | z | P>z | [95% Setting Interval] | |

| PMT Index | 0.044680 | 0.016209 | 2.76 | 0.006 | 0.01291 | 0.07645 |

| Scholarship | 0.117339 | 0.057898 | 2.03 | 0.043 | 0.00386 | 0.23082 |

| People with high school | 0.573630 | 0.261232 | 2.2 | 0.028 | 0.06162 | 1.08564 |

| Constant | -3.191815 | 1.122963 | -2.84 | 0.004 | -5.39278 | -0.99085 |

| Marginal effects after logit | |||||||

| y = | Pr(knowledge about climate change) (Predict) | ||||||

| 0.62386 | |||||||

| Variable | dy/dx | Std. Err. | z | P>z | [95% Setting Interval] | X | |

| PMT Index | 0.01048 | 0.00378 | 2.77 | 0.006 | 0.00307 | 0.01790 | 38.75810 |

| Scholarship | 0.02753 | 0.01353 | 2.04 | 0.042 | 0.00102 | 0.05405 | 7.38144 |

| People with high school | 0.13461 | 0.06082 | 2.21 | 0.027 | 0.01541 | 0.25381 | 1.91753 |

| Actions against climate change | |

| Start up in the Chota Valley an adaptive model against CC | 1 Adaptive Model Agreement versus CC |

| 0 No agreement on adaptive model versus CC | |

| Prepare society for the risks derived from CC | 1 Agreement to prepare society for CC risks |

| 0 I do not agree to prepare society for CC risks | |

| Integrate pilot projects of good adaptation practices against CC | 1 Agreement to integrate pilot projects of good practices against CC |

| 0 I do not agree to integrate pilot projects of good practices against CC | |

| Conserve the biodiversity of Chota Valley | 1 Agreement to conserve biodiversity of Chota Valley |

| 0 No agreement to conserve biodiversity of Chota Valley | |

| Has personally taken any measure or action against the CC | 1 If you have personally taken action against CC |

| 0 Has not personally taken action against CC | |

| What actions | 1 Regularly walks, rides a bike |

| 0 Other actions against the CC | |

| They believe that they could contribute to a greater extent in the fight against CC | 1 If you can contribute more against the CC |

| 0 Cannot contribute further against CC | |

| Why don't you do it | 1 No because they don’t know what to do |

| 0 For other reasons | |

| What do you think that future homes have systems to generate their own energy? | 1 Very good or good |

| 0 Bad, very bad NS NR | |

| What do you think about future homes having water reuse systems? | 1 Very good or good |

| 0 Bad, very bad NS NR | |

| What do you think that in the future there will be exclusive bicycle lanes? | 1 Very good or good |

| 0 Bad, very bad NS NR | |

| What do you think that in the future at least 50% of the energy consumed in the Chota Valley is renewable? | 1 Very good or good |

| 0 Bad, very bad NS NR | |

| What do you think about families sorting garbage in the future? | 1 Very good or good |

| 0 Bad, very bad NS NR | |

| PMT | A1 | A2 | |

| PMT | 1 | ||

| A1 | 0.1352 | 1 | |

| A2 | 0.1415 | 0.3393 | 1 |

| Logistic regression | Number of obs | = | 224 | |||

| LR chi 2 (3) | = | 3.97 | ||||

| prob > chi2 | = | 0.0463 | ||||

| Loglikelihood = -60.654332 | Pseudo -R2 | = | 0.0317 | |||

| Implement an adaptive model in the face of climate change | Coef. | Std. Err. | z | P>z | [95% Setting Interval] | |

| PMT Index | -0.02482 | 0.01244 | -2.00 | 0.046 | -0.0492 | -0.0004 |

| Constant | 3.70035 | 0.72512 | 5.10 | 0.000 | 2.2791 | 5.1216 |

| Marginal effects after logit | |||||||

| y = | Pr(actions against climate change) (Predict) | ||||||

| 0.92654 | |||||||

| variable | dy/dx | Std. Err. | z | P>z | [95% Setting Interval] | X | |

| PMT Index | -0.00169 | 0.00079 | -2.13 | 0.033 | -0.00324 | -0.00014 | 46.95490 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).