Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Autologous Angiogenic Precursor Cells and Nerve Cell Precursors Offer a Biomolecular Solution to Inflammation, Scarring and Apoptosis

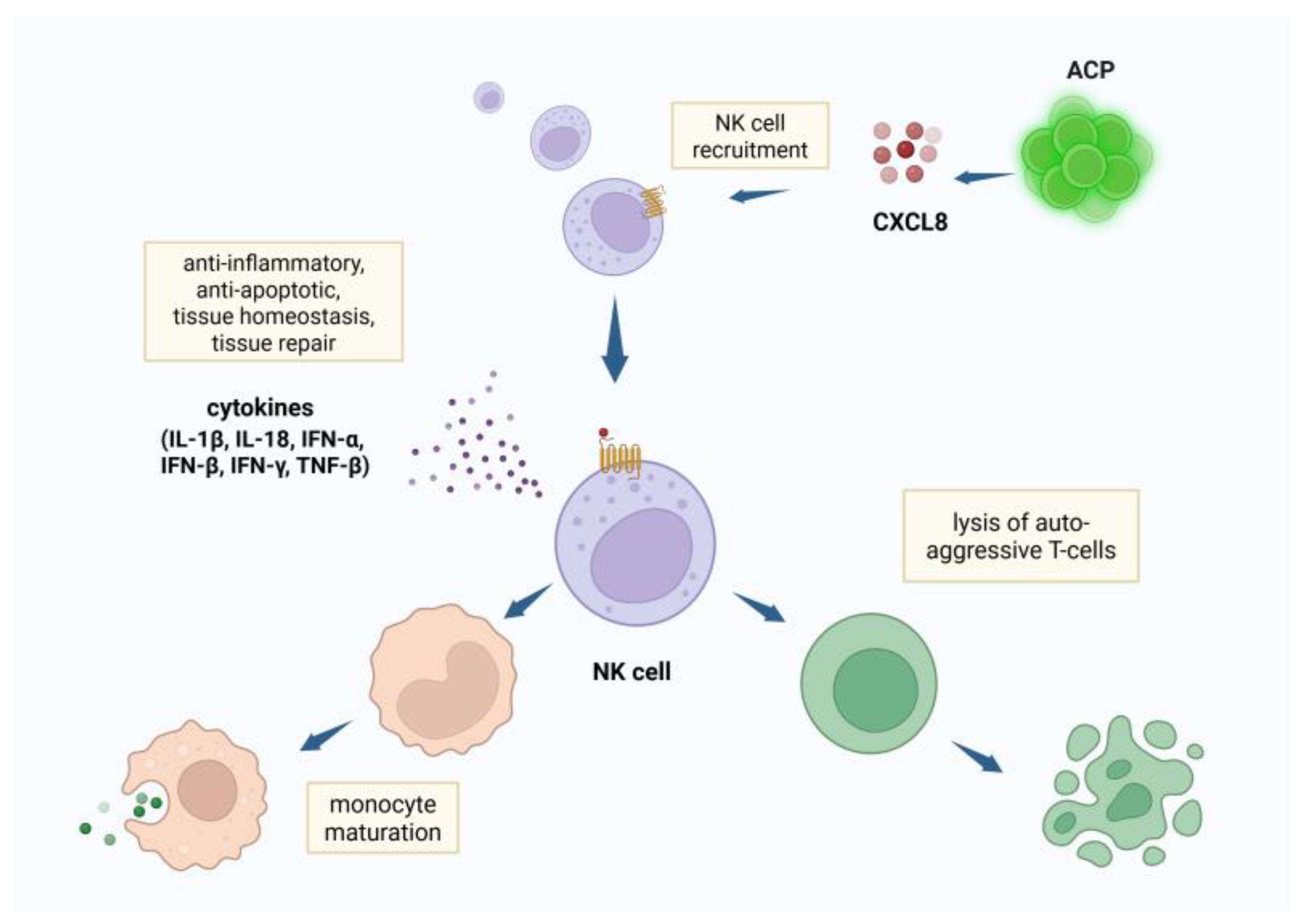

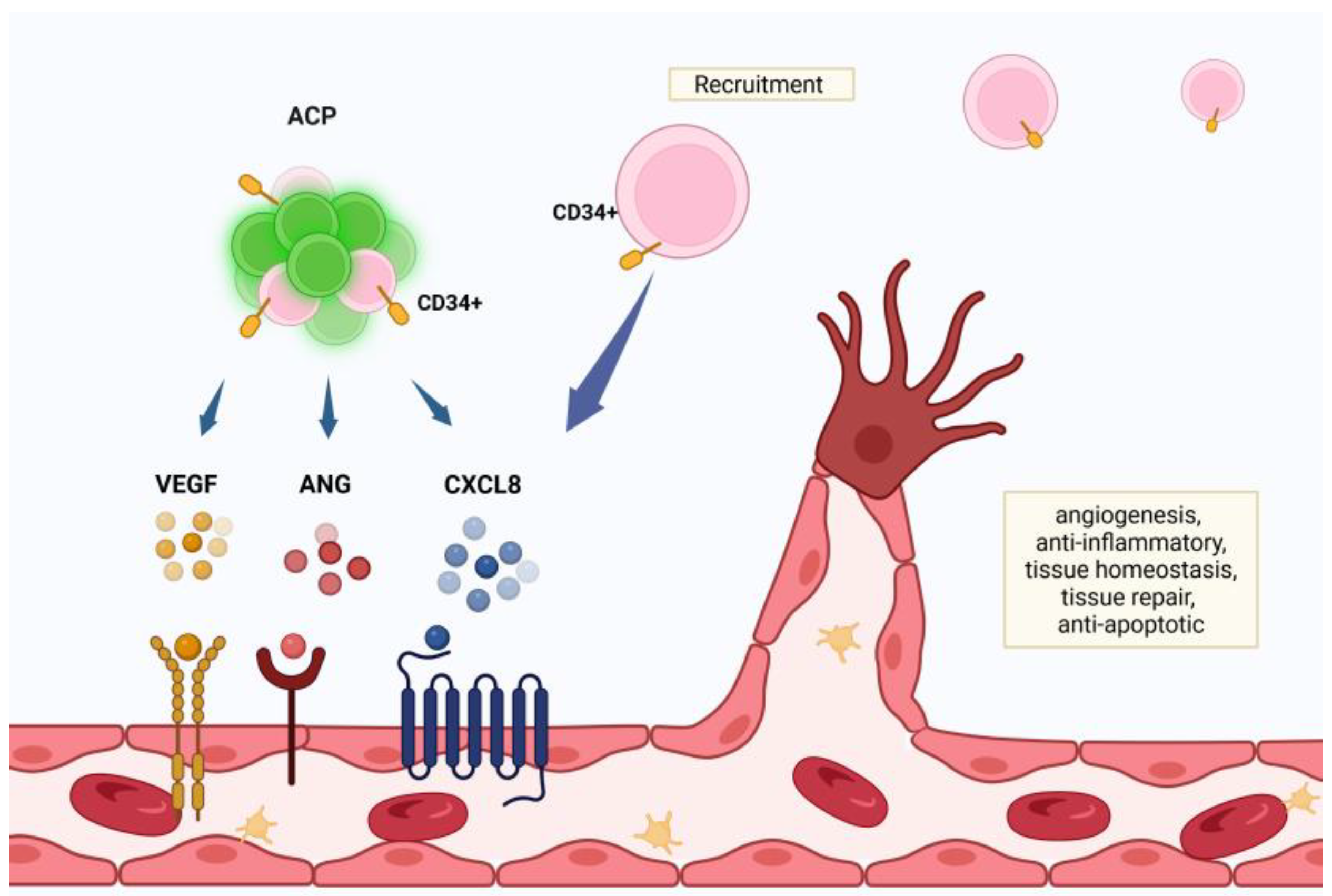

ACP Attract NK Cells; NK Cells Modulate Scarring

NF-κB Inhibits Apoptosis and Regulates Cell Survival

Neural Progenitor Cells (NCP)

Nerve Growth Factor Induces NF-κB

NSC May Mitigate the Pathophysiological Effects of CNS Injury Through Modulation of Expression of the N-Methyl D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptors

The CXCR4 /CXCL12 Axis Promotes ACP and NCP Migration Toward Areas of Hypoxic Injury and Stress

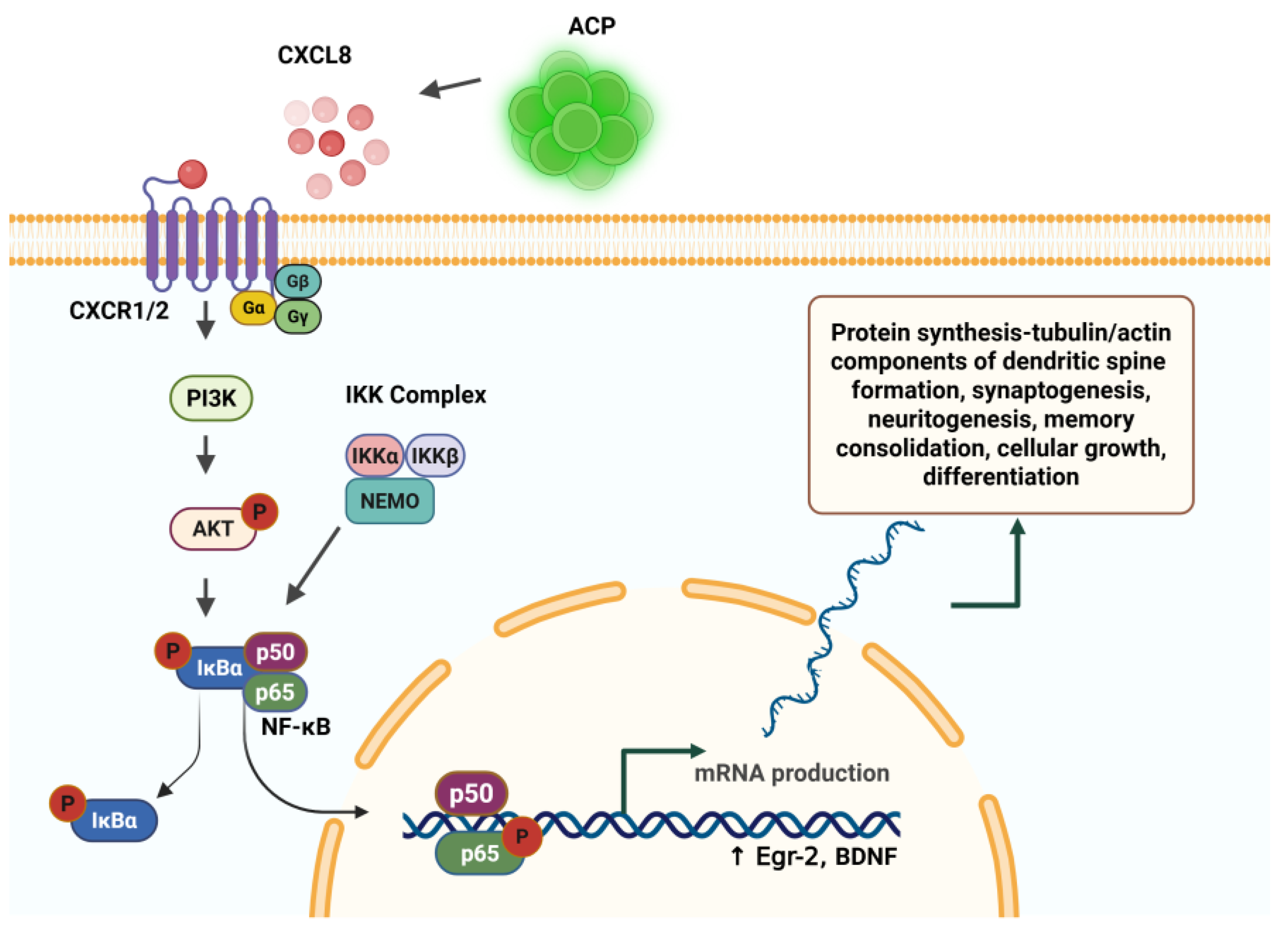

ACP Expression of IL-8 (CXCL8) Activates NF-κB – The “Learning Molecule”. NF-κB Is Essential to Synaptogenesis, Neuritogenesis, and Learning

Canonical and Non-Canonical Activation of NF-κB Factors

NF-κB Signaling Pathway Regulates Transcription in Memory Re-Consolidation

Information Storage Is a Function of Synaptogenesis

NSC Favor the Non-Inflammatory M2 Phenotype, Resulting in Less Inflammation and Less Scarring

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maiseli, B.; Abdalla, A.T.; Massawe, L.V.; Mbise, M.; Mkocha, K.; Nassor, N.A.; Ismail, M.; Michael, J.; Kimambo, S. Brain-computer interface: trend, challenges, and threats. Brain Inform. 2023, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kubben, P. Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Critical Assessment of Current Developments and Future Prospects. JMIR Neurotech 2024, 3, e60151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedell, H.W.; Capadona, J.R. Anti-inflammatory Approaches to Mitigate the Neuroinflammatory Response to Brain-Dwelling Intracortical Microelectrodes. J Immunol Sci. 2018, 2, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raposo, C.; Graubardt, N.; Cohen, M.; Eitan, C.; London, A.; Berkutzki, T.; Schwartz, M. CNS repair requires both effector and regulatory T cells with distinct temporal and spatial profiles. J Neurosci. 2014, 34, 10141–10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polikov, V.S.; Tresco, P.A.; Reichert, W.M. Response of brain tissue to chronically implanted neural electrodes. J Neurosci Methods. 2005, 148, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, R.W.; Humphrey, D.R. Long-term gliosis around chronically implanted platinum electrodes in the Rhesus macaque motor cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2006, 406, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filbin, M.T. Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003, 4, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubart, J.R.; Zare, A.; Fernandez-de-Castro, R.M.; Figueroa, H.R.; Sarel, I.; Tuchman, K.; Esposito, K.; Henderson, F.C.; von Schwarz, E. Safety and outcomes analysis: transcatheter implantation of autologous angiogenic cell precursors for the treatment of cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023, 14, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Henderson, F.C.; Sarel, I.; Tuchman, K.; Lewis, S.; Hsiang, Y. Angiogenic Precursor Cell Treatment of Critical Limb Ischemia Decreases Ulcer Size, Amputation and Death Rate: Re-Examination of phase II ACP NO-CLI Trial Data. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 2024, 5, 092–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, F.C.; Tuchman, K.; Sarel, I. Autologous Angiogenic Cell Precursors- A Molecular Strategy for the Treatment of Heart Failure: Response to Biocardia’s Cardiamp HF Trial. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 12 May. [CrossRef]

- Knorr, M.; Münzel, T.; Wenzel, P. Interplay of NK cells and monocytes in vascular inflammation and myocardial infarction. Front Physiol. 2014, 5, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ong, S.; Rose, N.R.; Čiháková, D. Natural killer cells in inflammatory heart disease. Clin Immunol. 2017, 175, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ong, S.; Ligons, D.L.; Barin, J.G.; Wu, L.; Talor, M.V.; Diny, N.; Fontes, J.A.; Gebremariam, E.; Kass, D.A.; Rose, N.R.; Čiháková, D. Natural killer cells limit cardiac inflammation and fibrosis by halting eosinophil infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2015, 185, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boukouaci, W.; Lauden, L.; Siewiera, J.; Dam, N.; Hocine, H.R.; Khaznadar, Z.; Tamouza, R.; Borlado, L.R.; Charron, D.; Jabrane-Ferrat, N.; Al-Daccak, R. Natural killer cell crosstalk with allogeneic human cardiac-derived stem/progenitor cells controls persistence. Cardiovasc Res. 2014, 104, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosshenrich, C.A.; Di Santo, J.P. Developmental programming of natural killer and innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013, 25, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.; Zhou, R.; Li, T.; Hua, Y.; Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Luo, S.; An, Q. The Molecular Role of Immune Cells in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Russo, R.C.; Garcia, C.C.; Teixeira, M.M.; Amaral, F.A. The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014, 10, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujanovic, L.; Ballard, W.; Thorne, S.H.; Vujanovic, N.L.; Butterfield, L.H. Adenovirus-engineered human dendritic cells induce natural killer cell chemotaxis via CXCL8/IL-8 and CXCL10/IP-10. Oncoimmunology. 2012, 1, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Walle, T.; Kraske, J.A.; Liao, B.; Lenoir, B.; Timke, C.; von Bohlen Und Halbach, E.; Tran, F.; Griebel, P.; Albrecht, D.; Ahmed, A.; Suarez-Carmona, M.; Jiménez-Sánchez, A.; Beikert, T.; Tietz-Dahlfuß, A.; Menevse, A.N.; Schmidt, G.; Brom, M.; Pahl, J.H.W.; Antonopoulos, W.; Miller, M.; Perez, R.L.; Bestvater, F.; Giese, N.A.; Beckhove, P.; Rosenstiel, P.; Jäger, D.; Strobel, O.; Pe’er, D.; Halama, N.; Debus, J.; Cerwenka, A.; Huber, P.E. Radiotherapy orchestrates natural killer cell dependent antitumor immune responses through CXCL8. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabh4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cambier, S.; Gouwy, M.; Proost, P. The chemokines CXCL8 and CXCL12: molecular and functional properties, role in disease and efforts towards pharmacological intervention. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023, 20, 217–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nurmi, A.; Lindsberg, P.J.; Koistinaho, M.; Zhang, W.; Juettler, E.; Karjalainen-Lindsberg, M.L.; Weih, F.; Frank, N.; Schwaninger, M.; Koistinaho, J. Nuclear factor-kappaB contributes to infarction after permanent focal ischemia. Stroke. 2004, 35, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z. H. , Tao L. Y., Chen X. (2007). Dual roles of NF-kappaB in cell survival and implications of NF-kappaB inhibitors in neuroprotective therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 28 1859–1872. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00741.x.

- Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Pagliari, L.J.; Perlman, H.; Yu, C.; Lin, A.; Pope, R.M. TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis of macrophages following inhibition of NF-kappa B: a central role for disruption of mitochondria. J Immunol. 2004, 172, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazarentzos, E.; Mahul-Mellier, A.L.; Datler, C.; Chaisaklert, W.; Hwang, M.S.; Kroon, J.; Qize, D.; Osborne, F.; Al-Rubaish, A.; Al-Ali, A.; Mazarakis, N.D.; Aboagye, E.O.; Grimm, S. IκΒα inhibits apoptosis at the outer mitochondrial membrane independently of NF-κB retention. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2814–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, J.L.; Kamata, H.; Karin, M. The anti-death machinery in IKK/NF-kappaB signaling. J Clin Immunol. 2005, 25, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, M.J.; Ghosh, S. IkappaB kinases: kinsmen with different crafts. Science. 1999, 284, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkett, M.; Gilmore, T.D. Control of apoptosis by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999, 18, 6910–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggirwar, S.B.; Sarmiere, P.D.; Dewhurst, S.; Freeman, R.S. Nerve growth factor-dependent activation of NF-kappaB contributes to survival of sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998, 18, 10356–10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hamanoue, M.; Middleton, G.; Wyatt, S.; Jaffray, E.; Hay, R.T.; Davies, A.M. p75-mediated NF-kappaB activation enhances the survival response of developing sensory neurons to nerve growth factor. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999, 14, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, A.A.; Sha, W.C.; Bronson, R.T.; Ghosh, S.; Baltimore, D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995, 376, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin AS, Jr. The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996, 14, 649–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, A.A.; Baltimore, D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996, 274, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Antwerp, D.J.; Martin, S.J.; Kafri, T.; Green, D.R.; Verma, I.M. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996, 274, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Van Antwerp, D.; Mercurio, F.; Lee, K.F.; Verma, I.M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999, 284, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foehr, E.D.; Lin, X.; O’Mahony, A.; Geleziunas, R.; Bradshaw, R.A.; Greene, W.C. NF-kappa B signaling promotes both cell survival and neurite process formation in nerve growth factor-stimulated PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 2000, 20, 7556–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sompol, P.; Xu, Y.; Ittarat, W.; Daosukho, C.; Clair, D.S. NF-κB-Associated MnSOD induction protects against β-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Mol Neurosci. 2006, 29, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.F.; Guo, F.; Cao, Y.Z.; Shi, W.; Xia, Q. Neuroprotection by manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) mimics: antioxidant effect and oxidative stress regulation in acute experimental stroke. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012, 18, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Massaad, C.A.; Klann, E. Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 2013–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, M.; Lee, H.; Bellas, R.E.; Schauer, S.L.; Arsura, M.; Katz, D.; FitzGerald, M.J.; Rothstein, T.L.; Sherr, D.H.; Sonenshein, G.E. Inhibition of NF-kappaB/Rel induces apoptosis of murine B cells. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4682–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xia, Y.; Rao, J.; Yao, A.; Zhang, F.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Lu, L. Lithium exacerbates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting GSK-3β/NF-κB-mediated protective signaling in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012, 697, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiningham, K.K.; Xu, Y.; Daosukho, C.; Popova, B.; St Clair, D.K. Nuclear factor kappaB-dependent mechanisms coordinate the synergistic effect of PMA and cytokines on the induction of superoxide dismutase 2. Biochem J. 2001, 353, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pizzi, M.; Goffi, F.; Boroni, F.; Benarese, M.; Perkins, S.E.; Liou, H.C.; Spano, P. Opposing roles for NF-κB/Rel factors p65 and c-Rel in the modulation of neuron survival elicited by glutamate and interleukin-1beta. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 20717–20723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Goodman, Y.; Luo, H.; Fu, W.; Furukawa, K. Activation of NF-kappaB protects hippocampal neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis: evidence for induction of manganese superoxide dismutase and suppression of peroxynitrite production and protein tyrosine nitration. J Neurosci Res. 1997, 49, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Christakos, S.; Mattson, M.P. Tumor necrosis factors protect neurons against metabolic-excitotoxic insults and promote maintenance of calcium homeostasis. Neuron. 1994, 12, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamatani, M.; Che, Y.H.; Matsuzaki, H.; Ogawa, S.; Okado, H.; Miyake, S.; Mizuno, T.; Tohyama, M. Tumor necrosis factor induces Bcl-2 and Bcl-x expression through NFkappaB activation in primary hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 8531–8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, L.; Klein, M.; Schlett, K.; Pfizenmaier, K.; Eisel, U.L. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity is enhanced by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation. Essential role of a TNF receptor 2-mediated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent NF-kappa B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279, 32869–32881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Culmsee, C.; Klumpp, S.; Krieglstein, J. Neuroprotection by transforming growth factor-beta1 involves activation of nuclear factor-kappaB through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular-signal regulated kinase1,2 signaling pathways. Neuroscience. 2004, 123, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, A.D.; Chakraborty-Sett, S.; Ramirez, S.H.; Sniderhan, L.F.; Williamson, A.L.; Maggirwar, S.B. Mechanism of NF-kappaB inactivation induced by survival signal withdrawal in cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004, 20, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, D.R.; Miller, F.D. Signal transduction by the neurotrophin receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997, 9, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, M.; Levi, A.; Chao, M.V. Differential expression of nerve growth factor receptors leads to altered binding affinity and neurotrophin responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993, 90, 7859–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barker, P.A.; Shooter, E.M. Disruption of NGF binding to the low affinity neurotrophin receptor p75LNTR reduces NGF binding to TrkA on PC12 cells. Neuron. 1994, 13, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W.; Mizu, R.K.; Kusumoto, H.; XiangWei, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W.; Amin, J.B.; Hu, C.; Kannan, V.; Keller, S.R.; Wilcox, W.R.; Lemke, J.R.; Myers, S.J.; Swanger, S.A.; Wollmuth, L.P.; Petrovski, S.; Traynelis, S.F.; Yuan, H. De novo GRIN variants in NMDA receptor M2 channel pore-forming loop are associated with neurological diseases. Hum Mutat. 2019, 40, 2393–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Yu, S.W.; Koh, D.W.; Lew, J.; Coombs, C.; Bowers, W.; Federoff, H.J.; Poirier, G.G.; Dawson, T.M.; Dawson, V.L. Apoptosis-inducing factor substitutes for caspase executioners in NMDA-triggered excitotoxic neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10963–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, I.S.; Jung, K.; Kim, M.; Park, K.I. Neural stem cells: properties and therapeutic potentials for hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in newborn infants. Pediatr Int. 2010, 52, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chang, S.; Li, W.; Tang, G.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.Y.; Wang, Y. cxcl12-engineered endothelial progenitor cells enhance neurogenesis and angiogenesis after ischemic brain injury in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tajiri, N.; Kaneko, Y.; Shinozuka, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Yankee, E.; McGrogan, M.; Case, C.; Borlongan, C.V. Stem cell recruitment of newly formed host cells via a successful seduction? Filling the gap between neurogenic niche and injured brain site. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e74857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ben-Hur, T. Reconstructing neural circuits using transplanted neural stem cells in the injured spinal cord. J Clin Invest. 2010, 120, 3096–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fandel, T.M.; Trivedi, A.; Nicholas, C.R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Martinez, A.F.; Noble-Haeusslein, L.J.; Kriegstein, A.R. Transplanted Human Stem Cell-Derived Interneuron Precursors Mitigate Mouse Bladder Dysfunction and Central Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2016, 19, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, W.M.; Stoesz, B.M.; Kelly, D.M.; Albensi, B.C. Roles for NF-κB and gene targets of NF-κB in synaptic plasticity, memory, and navigation. Mol Neurobiol. 2014, 49, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubin, F.D.; Johnston, L.D.; Sweatt, J.D.; Anderson, A.E. Kainate mediates nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hippocampus via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase. Neuroscience. 2005, 133, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, E.R. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialog between genes and synapses. Biosci Rep. 2004, 24, 475–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, A.; Raber, J.; Montano, M.; Foehr, E.; Han, V.; Lu, S.M.; Kwon, H.; LeFevour, A.; Chakraborty-Sett, S.; Greene, W.C. NF-kappaB/Rel regulates inhibitory and excitatory neuronal function and synaptic plasticity. Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 7283–7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freudenthal, R.; Romano, A. Participation of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors in long-term memory in the crab Chasmagnathus. Brain Res. 2000, 855, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meberg, P.J.; Kinney, W.R.; Valcourt, E.G.; Routtenberg, A. Gene expression of the transcription factor NF-kappa B in hippocampus: regulation by synaptic activity. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996, 38, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassed, C.A.; Willing, A.E.; Garbuzova-Davis, S.; Sanberg, P.R.; Pennypacker, K.R. Lack of NF-kappaB p50 exacerbates degeneration of hippocampal neurons after chemical exposure and impairs learning. Exp Neurol. 2002, 176, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenthal, R.; Romano, A.; Routtenberg, A. Transcription factor NF-kappaB activation after in vivo perforant path LTP in mouse hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2004, 14, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albensi, B.C.; Mattson, M.P. Evidence for the involvement of TNF and NF-kappaB in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Synapse. 2000, 35, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis-Donini, S.; Dellarole, A.; Crociara, P.; Francese, M.T.; Bortolotto, V.; Quadrato, G.; Canonico, P.L.; Orsetti, M.; Ghi, P.; Memo, M.; Bonini, S.A.; Ferrari-Toninelli, G.; Grilli, M. Impaired adult neurogenesis associated with short-term memory defects in NF-kappaB p50-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3911–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Huang, I.C.; Pizzi, M.; Spano, P.; Boroni, F.; Egli, R.; Desai, P.; Fitch, O.; Malone, L.; Ahn, H.J.; Liou, H.C.; Sweatt, J.D.; Levenson, J.M. Regulation of nuclear factor kappaB in the hippocampus by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2006, 26, 4870–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahn, H.J.; Hernandez, C.M.; Levenson, J.M.; Lubin, F.D.; Liou, H.C.; Sweatt, J.D. c-Rel, an NF-kappaB family transcription factor, is required for hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Learn Mem. 2008, 15, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Sullivan, N.C.; Croydon, L.; McGettigan, P.A.; Pickering, M.; Murphy, K.J. Hippocampal region-specific regulation of NF-kappaB may contribute to learning-associated synaptic reorganisation. Brain Res Bull. 2010, 81, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltschmidt, B.; Ndiaye, D.; Korte, M.; Pothion, S.; Arbibe, L.; Prüllage, M.; Pfeiffer, J.; Lindecke, A.; Staiger, V.; Israël, A.; Kaltschmidt, C.; Mémet, S. NF-kappaB regulates spatial memory formation and synaptic plasticity through protein kinase A/CREB signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 2936–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oikawa, K.; Odero, G.L.; Platt, E.; Neuendorff, M.; Hatherell, A.; Bernstein, M.J.; Albensi, B.C. NF-κB p50 subunit knockout impairs late LTP and alters long term memory in the mouse hippocampus. BMC Neurosci. 2012, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, F.Q.; Qiu, B.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Li, T.K.; Xie, Q.; Cui, D.J.; Huang, X.L.; Gan, H.T. Tetrandrine attenuates spatial memory impairment and hippocampal neuroinflammation via inhibiting NF-κB activation in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease induced by amyloid-β(1-42). Brain Res. 2011, 1384, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, E.; Freudenthal, R.; Maldonado, H.; Romano, A. Activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB by retrieval is required for long-term memory reconsolidation. Learn Mem. 2005, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alberini, C.M. Transcription factors in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2009, 89, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romano, A.; Freudenthal, R.; Merlo, E.; Routtenberg, A. Evolutionarily-conserved role of the NF-kappaB transcription factor in neural plasticity and memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2006, 24, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, S.W.; Hörster, D.; Furukawa, K.; Goodman, Y.; Krieglstein, J.; Mattson, M.P. Tumor necrosis factors alpha and beta protect neurons against amyloid beta-peptide toxicity: evidence for involvement of a kappa B-binding factor and attenuation of peroxide and Ca2+ accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995, 92, 9328–9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krushel, L.A.; Cunningham, B.A.; Edelman, G.M.; Crossin, K.L. NF-kappaB activity is induced by neural cell adhesion molecule binding to neurons and astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 2432–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberini, C.M.; Ledoux, J.E. Memory reconsolidation. Curr Biol. 2013, 23, R746–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federman, N.; de la Fuente, V.; Zalcman, G.; Corbi, N.; Onori, A.; Passananti, C.; Romano, A. Nuclear factor κB-dependent histone acetylation is specifically involved in persistent forms of memory. J Neurosci. 2013, 33, 7603–7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Artis, S.; Molfese, D.L.; Schumacher, A.; Sweatt, J.D.; Paylor, R.E.; Lubin, F.D. Histone methylation regulates memory formation. J Neurosci. 2010, 30, 3589–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boccia, M.; Freudenthal, R.; Blake, M.; de la Fuente, V.; Acosta, G.; Baratti, C.; Romano, A. Activation of hippocampal nuclear factor-kappa B by retrieval is required for memory reconsolidation. J Neurosci. 2007, 27, 13436–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carayol, N.; Chen, J.; Yang, F.; Jin, T.; Jin, L.; States, D.; Wang, C.Y. A dominant function of IKK/NF-kappaB signaling in global lipopolysaccharide-induced gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281, 31142–31151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubin, F.D.; Sweatt, J.D. The IkappaB kinase regulates chromatin structure during reconsolidation of conditioned fear memories. Neuron. 2007, 55, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lucchesi, W.; Mizuno, K.; Giese, K.P. Novel insights into CaMKII function and regulation during memory formation. Brain Res Bull. 2011, 85, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, P.; Clark, P.M.; Mason, D.E.; Peters, E.C.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C.; Baltimore, D. Activation of the transcriptional function of the NF-κB protein c-Rel by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Sci Signal. 2013, 6, ra75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hanover, J.A.; Krause, M.W.; Love, D.C. Bittersweet memories: linking metabolism to epigenetics through O-GlcNAcylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltschmidt, C.; Kaltschmidt, B.; Neumann, H.; Wekerle, H.; Baeuerle, P.A. Constitutive NF-kappa B activity in neurons. Mol Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 3981–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shih, V.F.; Tsui, R.; Caldwell, A.; Hoffmann, A. A single NFκB system for both canonical and non-canonical signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freudenthal, R.; Boccia, M.M.; Acosta, G.B.; Blake, M.G.; Merlo, E.; Baratti, C.M.; Romano, A. NF-kappaB transcription factor is required for inhibitory avoidance long-term memory in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2005, 21, 2845–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Moerman, A.M.; Barger, S.W. Neuronal kappa B-binding factors consist of Sp1-related proteins. Functional implications for autoregulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 44911–44919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.; Vargas, J.; Hoffmann, A. Signaling via the NFκB system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2016, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nader, K.; Schafe, G.E.; Le Doux, J.E. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 7: 17;406(6797), 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, E.; Freudenthal, R.; Maldonado, H.; Romano, A. Activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB by retrieval is required for long-term memory reconsolidation. Learn Mem. 2005, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheung, P.; Allis, C.D.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell. 2000, 103, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viatour, P.; Legrand-Poels, S.; van Lint, C.; Warnier, M.; Merville, M.P.; Gielen, J.; Piette, J.; Bours, V.; Chariot, A. Cytoplasmic IkappaBalpha increases NF-kappaB-independent transcription through binding to histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1 and HDAC3. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 46541–46548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Lin, Z.; SenBanerjee, S.; Jain, M.K. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated reduction of KLF2 is due to inhibition of MEF2 by NF-kappaB and histone deacetylases. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 5893–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freudenthal, R.; Locatelli, F.; Hermitte, G.; Maldonado, H.; Lafourcade, C.; Delorenzi, A.; Romano, A. Kappa-B like DNA-binding activity is enhanced after spaced training that induces long-term memory in the crab Chasmagnathus. Neurosci Lett. 1998, 242, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, E.; Freudenthal, R.; Romano, A. The IkappaB kinase inhibitor sulfasalazine impairs long-term memory in the crab Chasmagnathus. Neuroscience. 2002, 112, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meffert, M.K.; Chang, J.M.; Wiltgen, B.J.; Fanselow, M.S.; Baltimore, D. NF-kappa B functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003, 6, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.H.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, C.F.; Gean, P.W. A requirement of nuclear factor-kappaB activation in fear-potentiated startle. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 46720–46729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, M.C.; Dresselhaus, E.C.; De Biase, L.M.; Mihalas, A.B.; Bergles, D.E.; Meffert, M.K. A requirement for nuclear factor-kappaB in developmental and plasticity-associated synaptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2011, 31, 5414–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matsuzaki, M.; Honkura, N.; Ellis-Davies, G.C.; Kasai, H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004, 429, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nägerl, U.V.; Eberhorn, N.; Cambridge, S.B.; Bonhoeffer, T. Bidirectional activity-dependent morphological plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2004, 44, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Homma, K.J.; Poo, M.M. Shrinkage of dendritic spines associated with long-term depression of hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2004, 44, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopec, C.D.; Real, E.; Kessels, H.W.; Malinow, R. GluR1 links structural and functional plasticity at excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2007, 27, 13706–13718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nusser, Z.; Lujan, R.; Laube, G.; Roberts, J.D.; Molnar, E.; Somogyi, P. Cell type and pathway dependence of synaptic AMPA receptor number and variability in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1998, 21, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, M.; Ellis-Davies, G.C.; Nemoto, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Iino, M.; Kasai, H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saha, R.N.; Liu, X.; Pahan, K. Up-regulation of BDNF in astrocytes by TNF-alpha: a case for the neuroprotective role of cytokine. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006, 1, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, J.; Grill, R.J.; Dunn, T.J.; Bedi, S.; Labastida, J.A.; Hetz, R.A.; Xue, H.; Thonhoff, J.R.; DeWitt, D.S.; Prough, D.S.; Cox CSJr Wu, P. Human Neural Stem Cell Transplantation-Mediated Alteration of Microglial/Macrophage Phenotypes after Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell Transplant. 2016, 25, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, E.C.; Hunot, S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Sleiman, P.M.; Muqit, M.M.; Wood, N.W. Expanding insights of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006, 7, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive Astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity. 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Le, W. Differential Roles of M1 and M2 Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Serapide, M.F.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Leggio, L.; Vivarelli, S.; Iraci, N.; Pluchino, S.; Marchetti, B. Microglia Polarization, Gene-Environment Interactions and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: Emerging Roles of Glia-Neuron and Glia-Stem/Neuroprogenitor Crosstalk for Dopaminergic Neurorestoration in Aged Parkinsonian Brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peruzzotti-Jametti, L.; Bernstock, J.D.; Vicario, N.; Costa, A.S.H.; Kwok, C.K.; Leonardi, T.; Booty, L.M.; Bicci, I.; Balzarotti, B.; Volpe, G.; Mallucci, G.; Manferrari, G.; Donegà, M.; Iraci, N.; Braga, A.; Hallenbeck, J.M.; Murphy, M.P.; Edenhofer, F.; Frezza, C.; Pluchino, S. Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Succinate Licenses Neural Stem Cells to Suppress Chronic Neuroinflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2018, 22, 355–368.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Natteru, P.A.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Saeed, D.; Zahoor, H.; Zaheer, S.; Iyer, S.S.; Zaheer, A. Neuroinflammation Induces Neurodegeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Spine. 2016, 1, 1003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol. 4: 26;35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginhoux, F.; Greter, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Nandi, S.; See, P.; Gokhan, S.; Mehler, M.F.; Conway, S.J.; Ng, L.G.; Stanley, E.R.; Samokhvalov, I.M.; Merad, M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010, 330, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Gate, D.; Town, T. CNS infiltration of peripheral immune cells: D-Day for neurodegenerative disease? J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sedighzadeh, S.S.; Khoshbin, A.P.; Razi, S.; Keshavarz-Fathi, M.; Rezaei, N. A narrative review of tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer: regulation of macrophage polarization and therapeutic implications. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1889–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Omi, M.; Hata, M.; Nakamura, N.; Miyabe, M.; Ozawa, S.; Nukada, H.; Tsukamoto, M.; Sango, K.; Himeno, T.; Kamiya, H.; Nakamura, J.; Takebe, J.; Matsubara, T.; Naruse, K. Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells improves long-term diabetic polyneuropathy together with improvement of nerve morphometrical evaluation. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).