I. Introduction

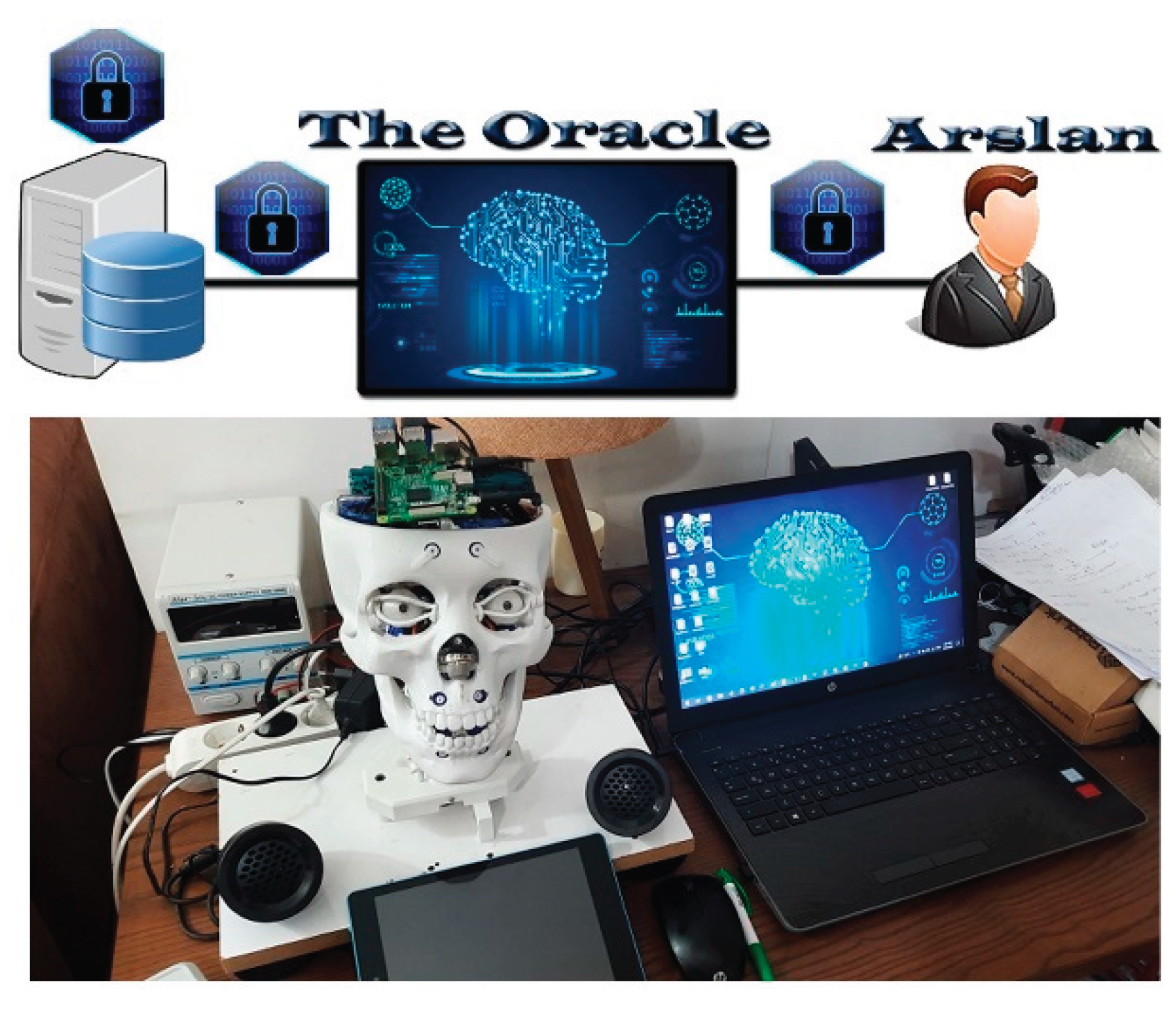

These days, wealthy nations view the tourist industry as one of the key pillars supporting their economies and promoting their cultures. The most significant issues that tourists encounter, however, are the language barrier and the dearth of adequate information regarding each nation’s tourist attractions. A Robotics Information System (

Figure 1) was created in order to address these issues [

1]. With the aid of vision [

2], audition [

3], speech, and other abilities, the humanoid robot Arslan [

1] can engage with people from the moment of their arrival until their departure (they will be present at airports, hotels, hospitals, etc.).

Since the system’s foundation is the provision and storage of tourist data in its database (such as personal data and travel schedules), the security of this sensitive data must be guaranteed by strengthening the RIS’s database security.

Traditional encryption methods like the Data Encryption Standard (DES) and the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) were assessed for their possible application in protecting communication between the database and the Oracle system during the early phases of system development. To enable safe data transfer between the two systems, a shared encryption key was created.

Nevertheless, a number of restrictions were found during the testing stage. Due to its vulnerability to compromise utilizing contemporary computational powers, “DES, being an older cryptographic algorithm with a relatively short key length (56 bits), was found to be particularly vulnerable to brute-force attacks” and is generally regarded as outdated [

4]. Although AES provides more robust encryption with varying key lengths (128, 192, or 256 bits), questions have been raised about its long-term robustness [

5]. Particularly, “if structural vulnerabilities within AES are discovered or if advancements in quantum computing materialize, the algorithm may be exposed to potential attacks” [

6]. “Reliance on encryption methods that are susceptible to future compromise is deemed unsuitable” [

7] considering the extremely sensitive nature of the material being handled. Consequently, it was determined that conventional symmetric encryption methods like DES and AES do not offer a strong enough degree of security to safeguard this type of sensitive data, especially in systems that need to be highly confidential and resistant to sophisticated attacks.

A public key and a private key are the two encryption keys used in asymmetric encryption algorithms, which are frequently employed for safe data transfer [

8]. In this case, an oracle system encrypts data before transmitting it using the public key. The database receives the encrypted data and decrypts it using the matching private key [

9]. Following decryption, the database sorts and encodes the data, among other necessary calculations, before storing it. This cryptographic technique has drawbacks even if it provides noticeably greater security than conventional symmetric encryption techniques. Though it still has some weaknesses, “asymmetric encryption is theoretically more resistant to brute force attacks due to the complexity of key generation and separation” [

10]. The ultimate threat posed by “advances in quantum computing” [

12] or “private key exposure, man-in-the-middle attacks” [

11] are examples of these vulnerabilities. The development and security of user tracking mechanisms will be the main emphasis of this study.

II. Methods

It is crucial to start by describing and elucidating the many techniques and strategies that were used during the process in order to give a thorough grasp of the solutions created to meet the identified issue. These techniques were chosen and used with care, taking into account the unique needs and difficulties of the system in question.

A. Database Arrangement:

As can be seen in the tables below, the database first divides the places that tourists are anticipated to visit into tables. In the database structure, the tourist attractions that are anticipated to draw tourists are first categorized and organized in distinct tables. As demonstrated in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, this classification makes data administration and retrieval more effective.

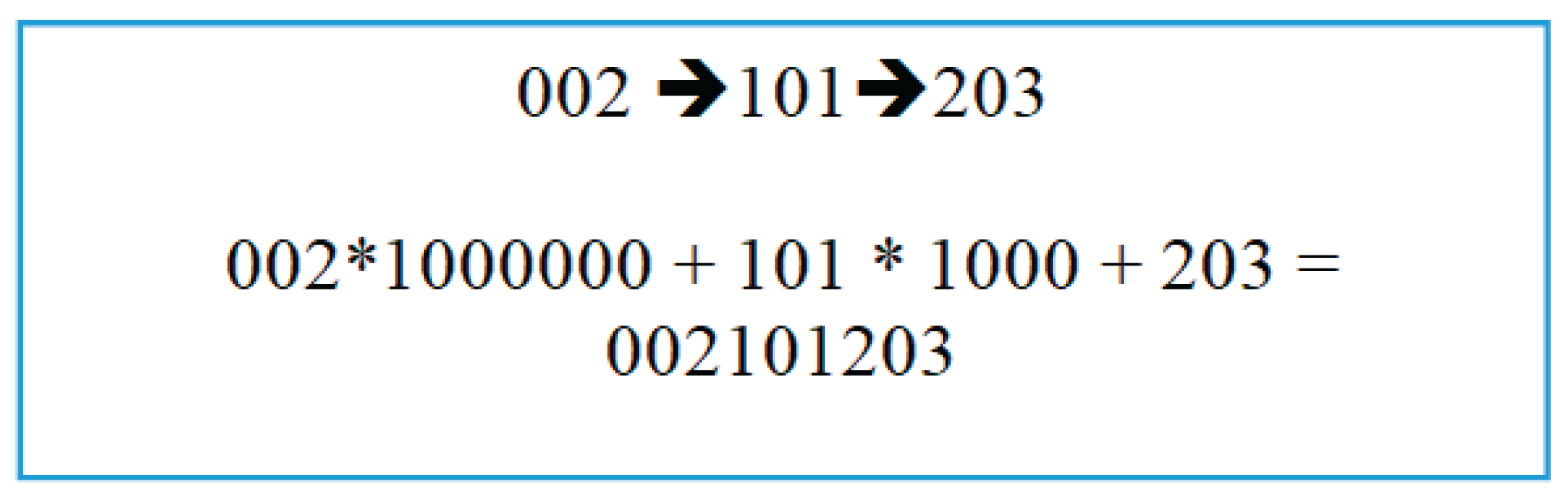

B. Mathematical Tracking System:

Following the database’s organization of the tourist destinations, this input data is then systematically incorporated into the robotics information system for real-world application. In order for the visitor to make a choice, the robotics system must first issue a request to access particular database tables that hold pertinent geographic data. The system obtains the location code that corresponds to the tourist’s first selection and multiplies it by one million. When a second site is chosen, its code is added to the original result after being multiplied by 1,000. The cumulative total from the first two phases is then immediately increased by the code of the third place that was chosen (as illustrated in

Figure 2). The precise order of the tourist-selected destinations is reflected in a single number identity generated by this computational process. The system can more effectively and precisely track and react to the visitor’s movements since each element of this number corresponds to a distinct location and is arranged chronologically based on the visitor’s choices.

It is essential that the data produced by the previously explained encoding method not be stored in its raw form due to the sensitivity of the resulting data. Before each storage procedure, encryption must be used to guarantee data security and shield it from unwanted access. As a result, two different encryption techniques have been put out to protect the data both during storage and transmission:

Proposal 1:

This method entails sharing an encryption key between the database and the Oracle system. The database uses this key to encrypt the requested data before transferring it when Oracle makes a data request. Oracle receives the encrypted data, decrypts it locally, adds or processes any information that is required, and then uses the same key to re-encrypt the updated data. Later, the database receives the re-encrypted data, decrypts it, and stores it safely. Both symmetric and asymmetric encryption algorithms will be applied in this situation.

Proposal 2:

The second strategy, on the other hand, gives Oracle sole responsibility for encryption. By limiting access to the encryption mechanism, Oracle improves data security in this situation by encrypting data using a private key that is not shared with the database. After that, the database receives the encrypted data and applies the required mathematical change without decrypting it. The outcome of processing and encryption is immediately saved in the database. This approach improves privacy and control by guaranteeing that private data is not accessible to the database itself. Fully homomorphic encryption, or homomorphic encryption, is used to achieve this.

Any possible breach might result in major privacy violations and unapproved exploitation due to the extremely sensitive nature of the data involved, especially that which is linked to tracking travelers’ movements and trip histories. As a result, even with enhanced security, systems handling private information and real-time location data might not be adequately protected by asymmetric encryption.

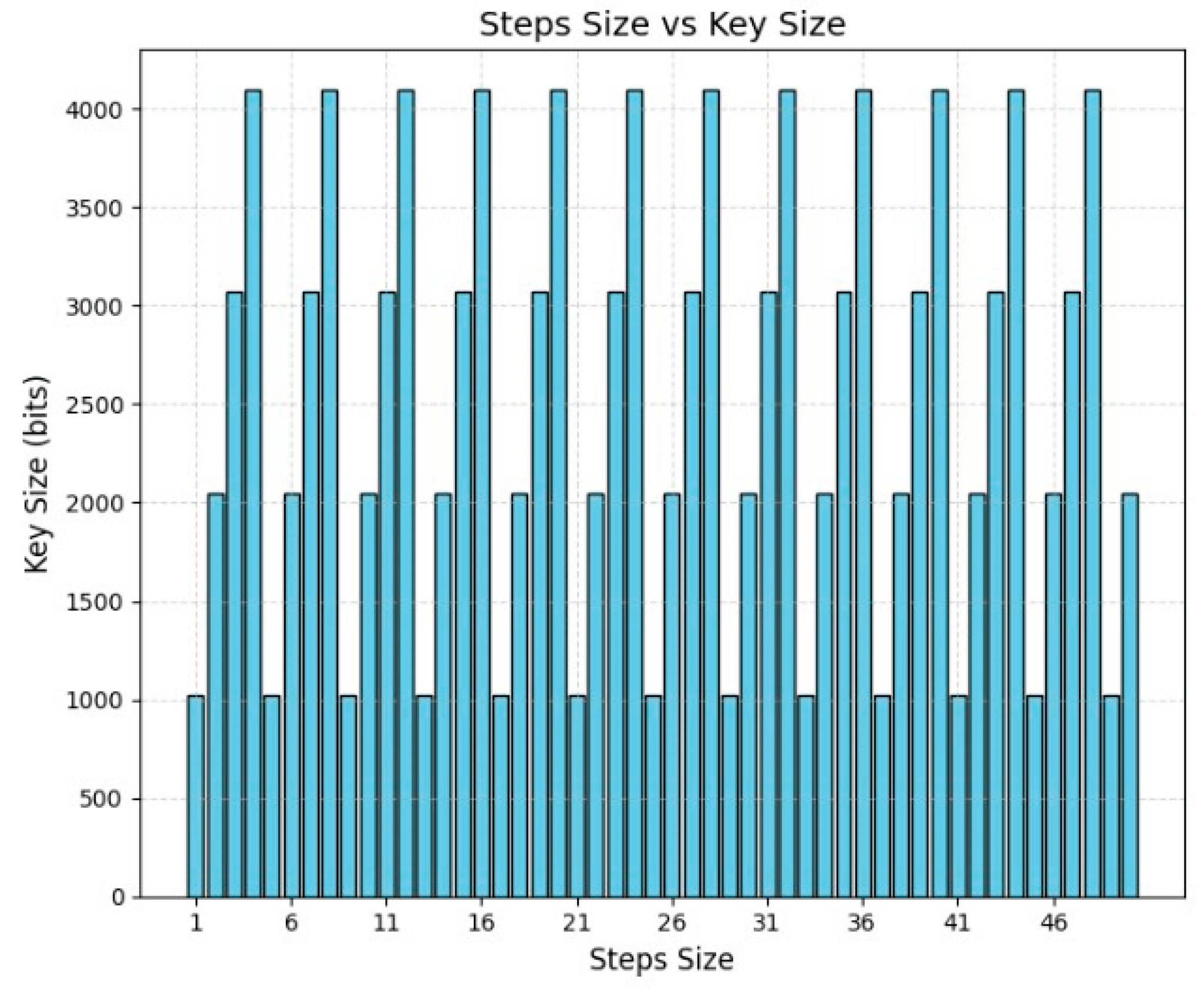

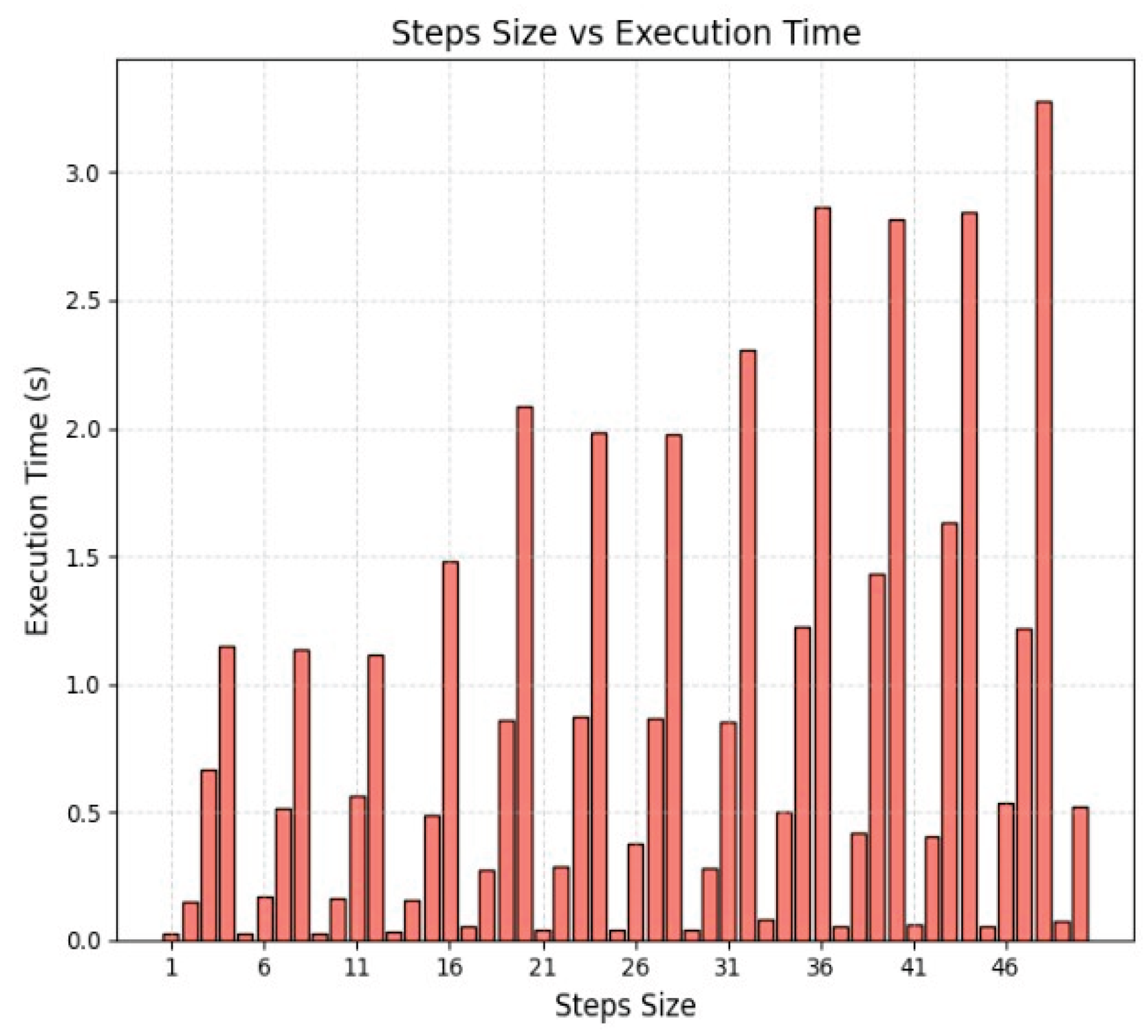

C.Homomorphic Encryption Techniques:

Symmetric encryption, with a focus on Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), was the last encryption technique investigated during system development. This method eliminates the need for decryption altogether by allowing computations to be done directly on encrypted data. According to earlier studies, “Homomorphic encryption systems can compute on encrypted data without requiring the private key.” The result of these computations is encrypted in and of itself. Any calculations performed on the encrypted data yield the same outcome as when the data was raw. [

13] Oracle used a private key that was only known to it to control encryption and decryption in this implementation. Confidentiality was maintained during the safe transmission and database storage of the encrypted data.

Without having access to the raw, unencrypted data, the database then carried out the required calculations, including structuring and categorizing the data. Sensitive information was protected throughout the data lifecycle by securely storing the processed and encrypted data in the database.

When compared to other encryption methods that have been examined, such symmetric (DES and AES) or asymmetric encryption, this approach showed notable gains in security and privacy. Enhanced resilience to a variety of assaults, such as those targeting key compromise or data interception during transmission, is provided by fully homomorphic encryption. Applications requiring sensitive and privacy-sensitive data, such monitoring visitor movements and managing private location data, are especially well-suited for its capacity to facilitate secure calculations on encrypted data.

IV. Conclusion

By the end of this study, a thorough grasp of the several encryption methods that can be used to handle extremely sensitive data had been attained. Out of all the techniques examined, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) was found to be the most appropriate strategy given the state of technology today. In addition to offering strong defense against common cyberthreats, such as man-in-the-middle assaults, this method makes it possible to do intricate calculations on encrypted data directly, doing away with the requirement for decryption altogether.

FHE’s deployment was essential to protecting travelers’ privacy, especially when it came to tracking their travels between locations. Additionally, by facilitating the safe processing of real-time data, this method improved the robotic information system’s performance and decision-making capacities. In the end, it is anticipated that the project’s results will enhance the overall traveler experience and benefit the tourism industry. By doing this, it encourages tourists to make happy, long-lasting experiences while also boosting economic development and raising awareness of local cultural assets around the world.

Given its suitability for protecting the kind of sensitive data involved in tracking tourist activities, we have chosen fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) as the main cryptographic technique at this point in the project. Our future development goals, however, involve looking into different encryption methods that provide more effective key management, especially ones that can accommodate a wider range of operations throughout several phases of travelers’ trip monitoring. This approach seeks to preserve the highest standards of data integrity and secrecy while improving the system’s scalability and overall performance.

References

- Elaff, “Robotic Information System (RIS): Design of Humanoid Robot’s Head Based on Human Biomechanics”, El-Cezeri Journal of Science and Engineering, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 420–432, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Guemmam and I. Elaff, “Human Face Localization in 3D For Humanoid Robot Vision,” 2025 7th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (ICHORA), Ankara, Turkiye, 2025, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Al Karaki and I. Elaff, “Modelling Humanoid Robot Audition for Sound Source Localization Using Artifical Neural Network,” 2025 7th International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (ICHORA), Ankara, Turkiye, 2025, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- B. Schneier, Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C , 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: Wiley, 1996.

- J. Daemen and V. Rijmen, The Design of Rijndael: AES - The Advanced Encryption Standard . Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2002.

- L. Chen et al., “Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography,” National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), NISTIR 8105, 2016. [Online].Available:https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2016/NIST.IR.8105.pdf.

- G.Alagic et al., “NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization,” National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), 2022. [Online].Available:https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography.

- W. Stallings, Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice , 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson, 2016.

- J. Menezes, P. C. van Oorschot, and S. A. Vanstone, Handbook of Applied Cryptography . Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, 1996.

- D. R. Stinson and M. B. Paterson, Cryptography: Theory and Practice , 4th ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press, 2018.

- C. Mitchell, “Security implications of asymmetric cryptography in practice,” IEEE Security & Privacy , vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 45–52, Mar./Apr. 2017.

- L. Chen et al., “Report on Post-Quantum Cryptography,” National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), NISTIR 8105, 2016. [Online].Available:https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2016/NIST.IR.8105.pdf.

- Mahmood, Z. H., & Ibrahem, M. K. (2018). New fully homomorphic encryption scheme based on multistage partial homomorphic encryption applied in cloud computing. 2018 1st Annual International Conference on Information and Sciences (AiCIS), 182–186. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).