Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Food as a Modifiable Cd Exposure Route

2.1. Exposure Limits

2.2. Populations At-Risk for Dietary Cd Exposure and Adverse Health Effects

2.3. A Broad Range of Adverse Health Effects of Cd

3. Cd Exposure and Hypertension

3.1. Hypertension Prevalence

3.2. Resistance Hypertension: An Emerging Challenge

3.3. Cd as a Risk Factor for Hypertension and CKD: Epidemiolical Data

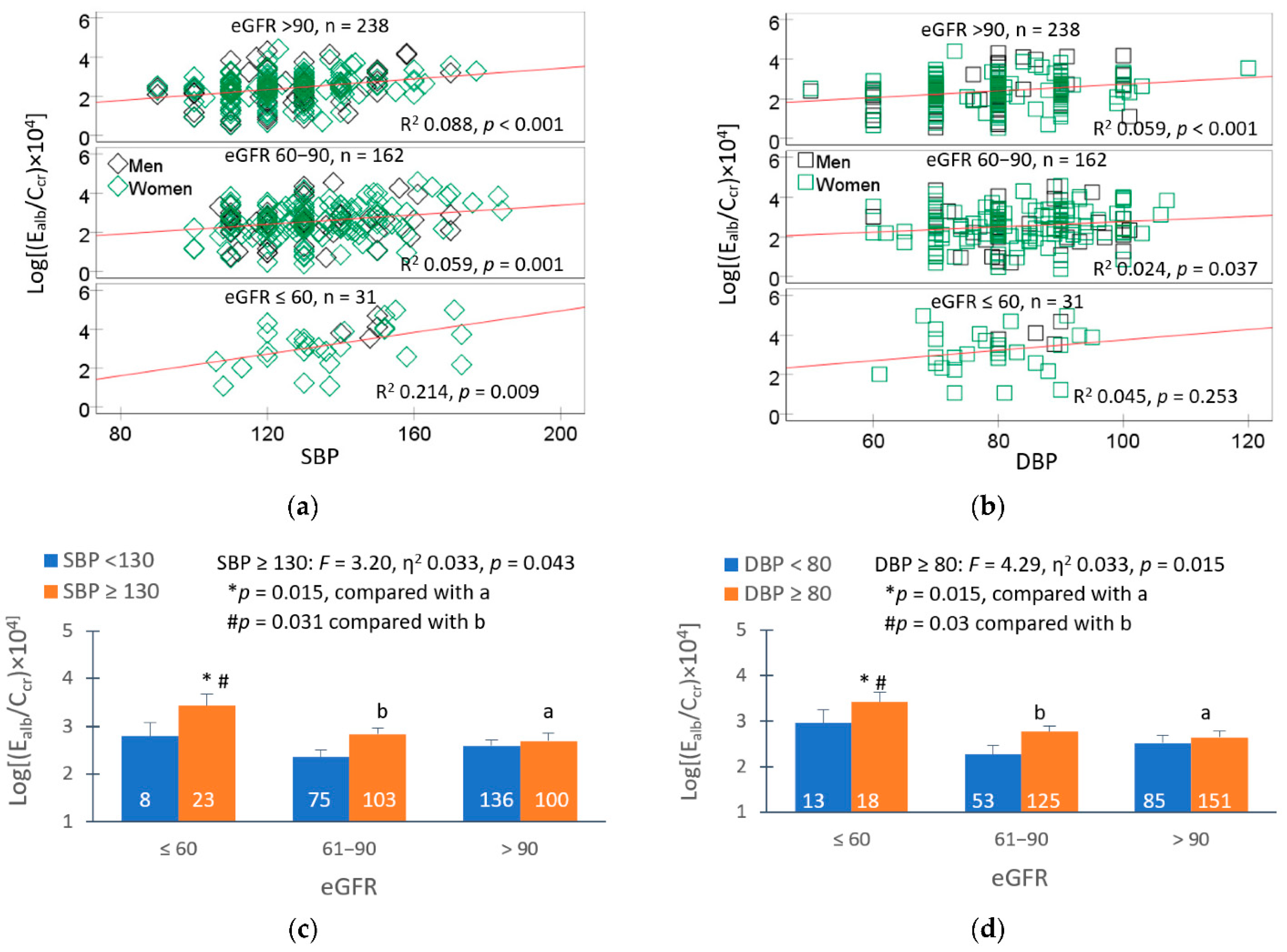

3.4. Albuminuria in Cd-Exposed People

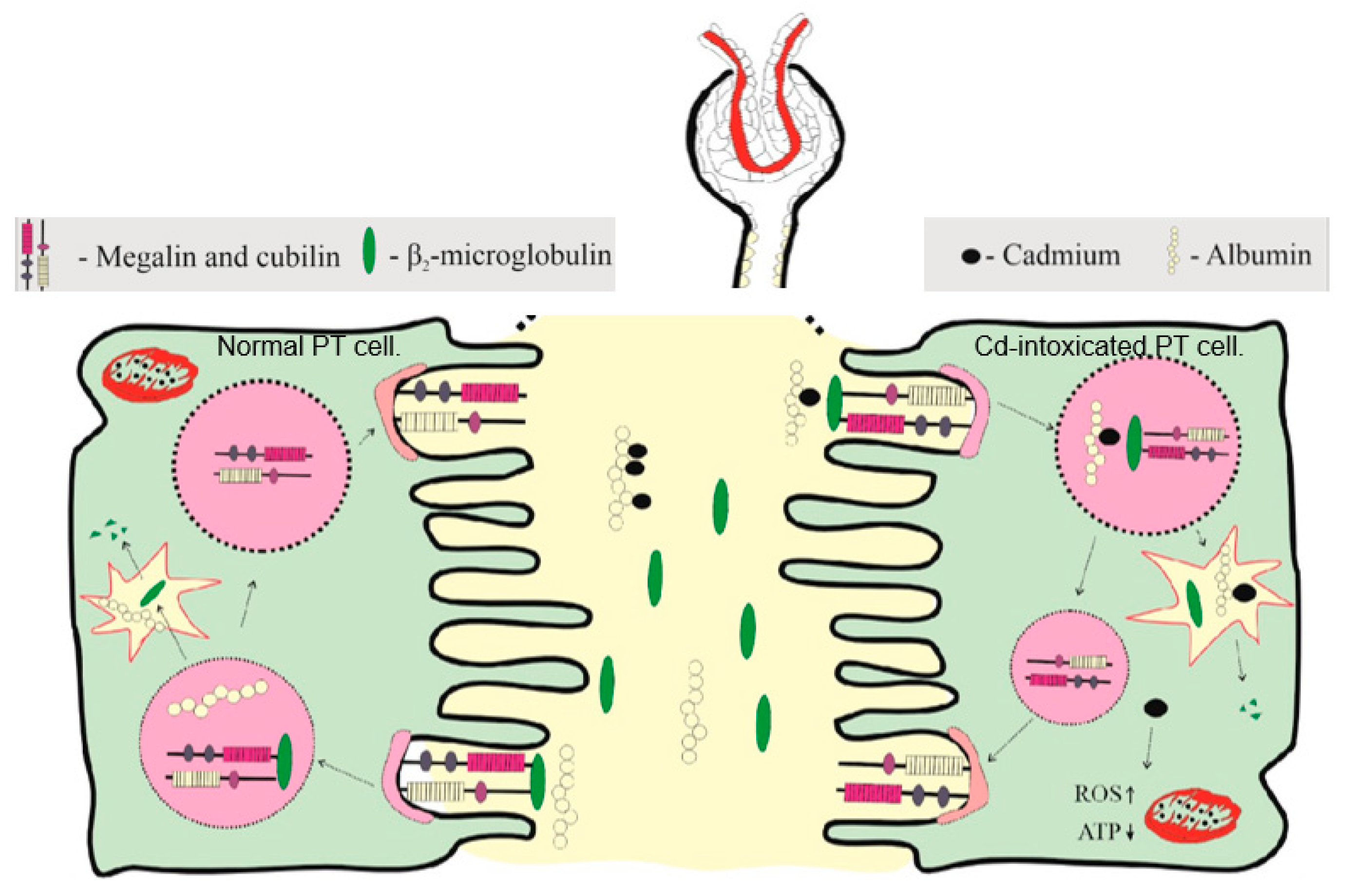

3.4.1. Tubular Handling of Albumin

3.4.2. Moderate-to-High Exposure to Cd

3.4.3. Low-to-Moderate Exposure to Cd

3.5. The Kidney and Gender Differences in Cd-Induced Hypertension

3.5.1. Cd and Kidney’s Role in Blood Pressure Regulation

3.5.2. The Increment of Tubular Avidity for Filtered Sodium After Cd Exposure

3.5.3. Gender Differences in Cd-Induced Hypertension

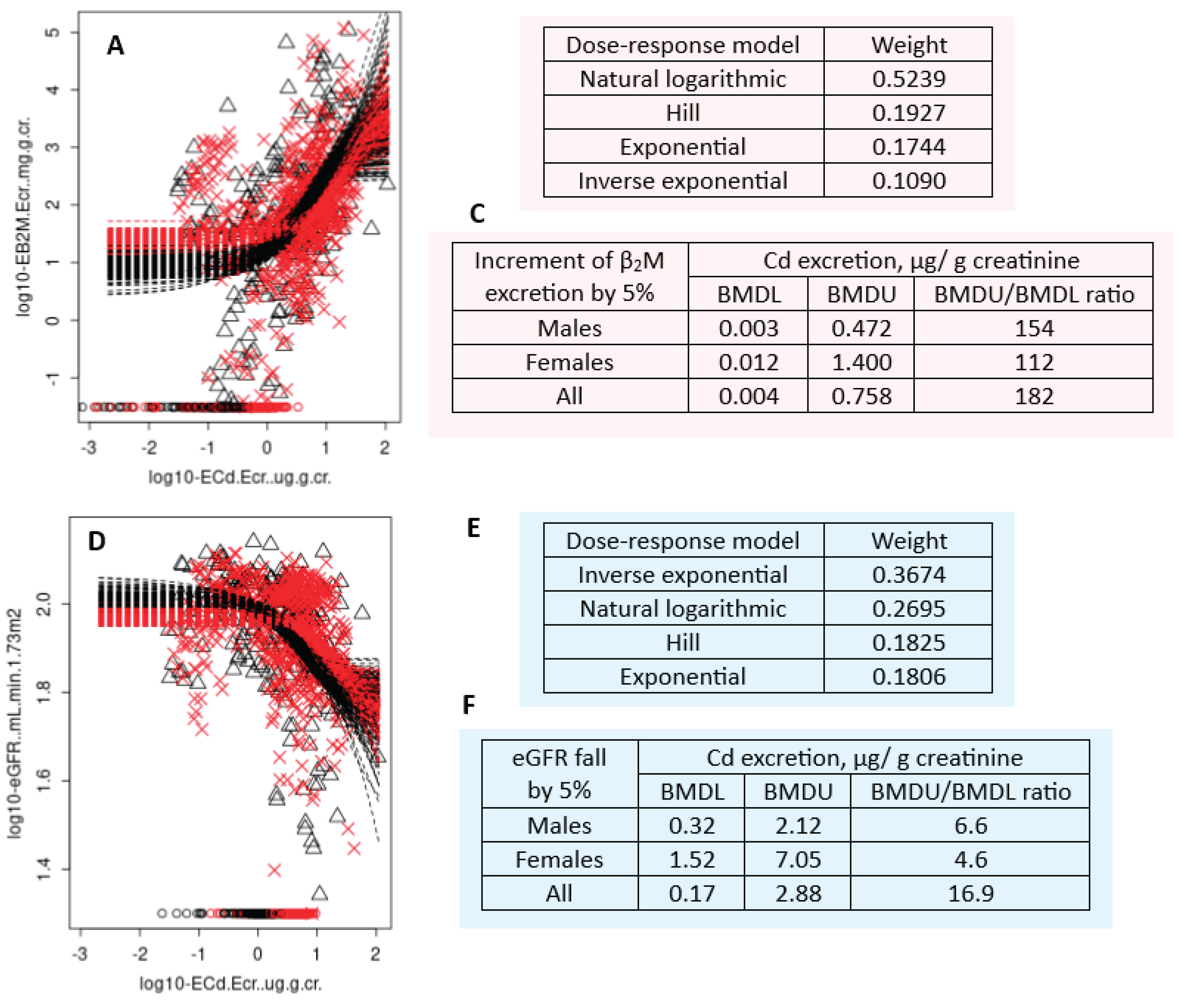

4. Critical Exposure Levels of Cd

4.1. Benchmark Dose Limit (BMDL)

4.2. JECFA and EFSA Dietary Cd Exposure Guidelines and Thresholds

4.3. Falling eGFR as an Early Warning Sign of Cd Nephrotoxicity

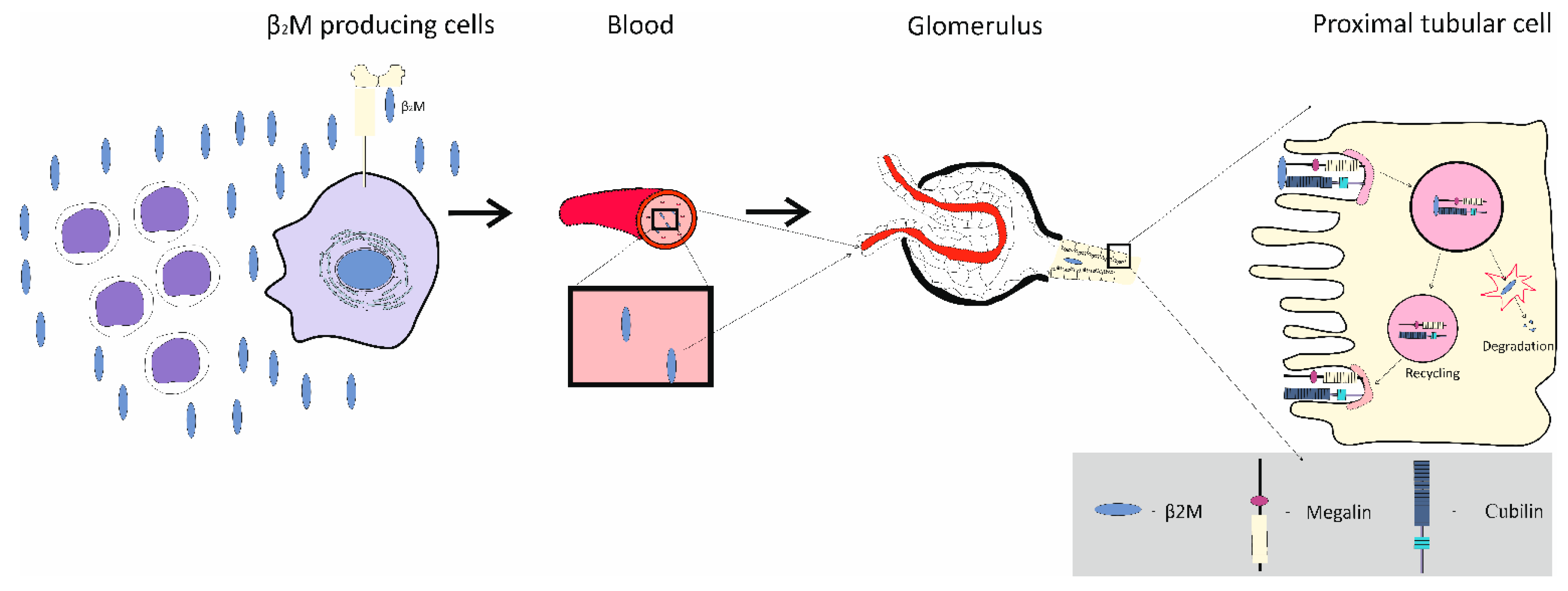

4.4. Use of β2M Excretion as Indicator of Cd Effect on Proximal Tubules?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | albumin-to-creatinine ratio |

| β2M | β2-microglobulin |

| BMDL | Benchmark dose limit |

| BMR | Benchmark dose response |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Cr | Chromium |

| CKM | Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome |

| Ccr | Creatinine clearance |

| CYP4A11 | Cytochrome P450 4A11 |

| CYP4F2 | Cytochrome P450 4F2 |

| cGAS-STING | cyclic GMP-AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes |

| DMT1 | Divalent metal transporter1 |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| JECFA | Joint Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives and Contaminants |

| 20-HETE | 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| NAG | N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase |

| NFE2L2 | NFE2 like BZIP transcription factor 2 |

| NF-кB | nuclear factor-kappaB |

| TRV | Toxicological Reference Value |

| ZIP8 | Zrt- and Irt-related protein 8 |

References

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. Estimation of health risks associated with dietary cadmium exposure. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.J.; Bank, M.S.; O'Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific opinion on cadmium in food. EFSA J. 2009, 980, 1–139. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Statement on tolerable weekly intake for cadmium. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick, M.D.; Dolan, K.G.; Horbinski, C.; Ghio, A.J.; Higgins, D.; Porubcin, M.; Moore, E.G.; Hainsworth, L.N.; Umbreit, J.N.; Conrad, M.E.; et al. DMT1: A mammalian transporter for multiple metals. Biometals 2003, 16, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydemir, T.B.; Cousins, R.J. The multiple faces of the metal transporter ZIP14 (SLC39A14). J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Ohba, K. Involvement of metal transporters in the intestinal uptake of cadmium. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.; Danko, T.; Bergeron, M.J.; Balazs, B.; Suzuki, Y.; Zsembery, A.; Hediger, M.A. Heavy metal cations permeate the TRPV6 epithelial cation channel. Cell Calcium 2011, 49, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.; Montalbetti, N.; Franz, M.C.; Graeter, S.; Simonin, A.; Hediger, M.A. Human TRPV5 and TRPV6: Key players in cadmium and zinc toxicity. Cell Calcium 2013, 54, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.; Shawki, A.; Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E.; Mackenzie, B. Functional properties of human ferroportin, a cellular iron exporter reactive also with cobalt and zinc. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014, 306, C450–C459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, E.; Lin, W.; Chai, J.; Hershfinkel, M.; Fu, D.; Sekler, I. Histidine pairing at the metal transport site of mammalian ZnT transporters controls Zn2+ over Cd2+ selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7202–7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Nishijo, M.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Source and Pathophysiologic Significance of Excreted Cadmium. Toxics 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinder, C.G.; Lind, B.; Kjellström, T.; Linnman, L.; Friberg, L. Cadmium in kidney cortex, liver, and pancreas from Swedish autopsies. Estimation of biological half time in kidney cortex, considering calorie intake and smoking habits. Arch. Environ. Health 1976, 31, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwazono, Y.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Nishijo, M.; Honda, R.; Kobayashi, E.; Dochi, M.; Nogawa, K. Biological half-life of cadmium in the urine of inhabitants after cessation of cadmium exposure. Biomarkers 2009, 14, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, M.; Suwazono, Y.; Kido, T.; Nishijo, M.; Honda, R.; Kobayashi, E.; Nogawa, K.; Nakagawa, H. Estimation of biological half-life of urinary cadmium in inhabitants after cessation of environmental cadmium pollution using a mixed linear model. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2015, 32, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thévenod, F.; Lee, W.K.; Garrick, M.D. Iron and cadmium entry into renal mitochondria: Physiological and toxicological implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branca, J.J.V.; Pacini, A.; Gulisano, M.; Taddei, N.; Fiorillo, C.; Becatti, M. Cadmium-induced cytotoxicity: Effects on mitochondrial electron transport chain. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 604377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.T.; Liu, T.B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Lian, C.Y.; Wang, L. HO-1 activation contributes to cadmium-induced ferroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells via increasing the labile iron pool and promoting mitochondrial ROS generation. Chem Biol Interact. 2024, 399, 111152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.K.; Thévenod, F. Cell organelles as targets of mammalian cadmium toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1017–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Guo, C.; Ruan, J.; Ning, B.; Wong, C.K.-C.; Shi, H.; Gu, J. Cadmium disrupted ER Ca2+ homeostasis by inhibiting SERCA2 expression and activity to induce apoptosis in renal proximal tubular cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. Role of subcellular calcium redistribution in regulating apoptosis and autophagy in cadmium-exposed primary rat proximal tubular cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 164, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.F.; Liu, T.B.; Chen, K.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Lian, C.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. Cadmium targeting transcription factor EB to inhibit autophagy-lysosome function contributes to acute kidney injury. J. Adv Res. 2025, 72, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.Y.; Liang, N.N.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ren, Y.H.; Wu, W.Z.; Liu, Z.B.; He, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.H.; Huang, Y.C.; Zhang, T.; et al. Mitochondrial GPX4 acetylation is involved in cadmium-induced renal cell ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2024, 73, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Long, M.; Dong, W.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, Q.; Ping, Y.; Zou, H.; Song, R.; et al. Cadmium Induces Kidney Iron Deficiency and Chronic Kidney Injury by Interfering with the Iron Metabolism in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suomi, J.; Valsta, L.; Tuominen, P. Dietary Heavy Metal Exposure among Finnish Adults in 2007 and in 2012. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Matsuda, R.; Uneyama, C. Dietary exposure of the Japanese general population to elements: Total diet study 2013–2018. Food Saf. 2022, 10, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, E.; Dias, M.G.; Oliveira, L. The first harmonised total diet study in Portugal: Arsenic, cadmium and lead exposure assessment. Chemosphere 2025, 372, 144003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman-Pennesi, D.; Winfield, S.; Gavelek, A.; Santillana Farakos, S.M.; Spungen, J. Infants’ and young children's dietary exposures to lead and cadmium: FDA total diet study 2018-2020. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2024, 41, 1454–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S. Environmental Cadmium Exposure Limits and Thresholds for Adverse Effects on Kidneys. J. Environ. Expose. Assess. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, R.; Bennett, D.; Cassady, D.; Frost, J.; Ritz, B.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Cancer and non-cancer health effects from food contaminant exposures for children and adults in California: a risk assessment. Environ Health 2012, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, B.M.; Schaefer, H.R.; Middleton, K.B. A scoping review of infant and children health effects associated with cadmium exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 131, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.R.; Flannery, B.M.; Crosby, L.M.; Pouillot, R.; Farakos, S.M.S.; Van Doren, J.M.; Dennis, S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Middleton, K. Reassessment of the cadmium toxicological reference value for use in human health assessments of foods. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 144, 105487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skröder, H.; Hawkesworth, S.; Kippler, M.; El Arifeen, S.; Wagatsuma, Y.; Moore, S.E.; Vahter, M. Kidney function and blood pressure in preschool-aged children exposed to cadmium and arsenic--potential alleviation by selenium. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, E.; Tamayo-Ortiz, M.; Ariza, A.C.; Ortiz-Panozo, E.; Deierlein, A.L.; Pantic, I.; Tolentino, M.C.; Estra-da-Gutiérrez, G.; Parra-Hernández, S.; Espejel-Núñez, A.; et al. Early-Life Dietary Cadmium Exposure and Kidney Function in 9-Year-Old Children from the PROGRESS Cohort. Toxics 2020, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, T.; Wise, L.A.; Vinceti, M. Cadmium exposure and risk of diabetes and prediabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzelloni, P.; Urbano, T.; Wise, L.A.; Vinceti, M.; Filippini, T. Cadmium exposure and cardiovascular disease risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ, Pollut. 2024, 345, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doccioli, C.; Sera, F.; Francavilla, A.; Cupisti, A.; Biggeri, A. Association of cadmium environmental exposure with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzelloni, P.; Giuliano, V.; Wise, L.A.; Urbano, T.; Baraldi, C.; Vinceti, M.; Filippini, T. Cadmium exposure and risk of hypertension: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 263 Pt 1, 120014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Su, W.; Li, N.; Song, Q.; Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Li, Y.; Lowe, S.; Bentley, R.; Zhou. Z.; et al. Association of urinary or blood heavy metals and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 67483–67503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterwijk, M.M.; Hagedoorn, I.J.M.; Maatman, R.G.H.J.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Navis, G.; Laverman, G.D. Cadmium, active smoking and renal function deterioration in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Perrais, M.; Golshayan, D.; Wuerzner, G.; Vaucher, J.; Thomas, A.; Marques-Vidal, P. Association between urinary heavy metal/trace element concentrations and kidney function: A prospective study. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 18, sfae378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S. Is Environmental Cadmium Exposure Causally Related to Diabetes and Obesity? Cells 2024, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, T.; Borghi, C.; Charchar, F.; Khan, N.A.; Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Ramirez, A.; Schlaich, M.; Stergiou, G.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Wainford, R.D.; Williams, B.; Schutte, A.E. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1334–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Mechanisms of sex and gender differences in hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2023, 37, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, P.J.; Currie, G.; Delles, C. Sex differences in the prevalence, outcomes and management of hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2022, 24, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufcourt, L.; Zins, M.; Berkman, L.F.; Grimaud, O. Socioeconomic disparities and risk of hypertension among older Americans: the Health and Retirement Study. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufcourt, L.; Deguen, S.; Bayat, S.; Paillard, F.; Zins, M.; Grimaud, O. Geographical variations in the prevalence of hypertension in France: Cross-sectional analysis of the CONSTANCES cohort. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.Y.; Zaman, M.M.; Ahmed, J.U.; Choudhury, S.R.; Khan, H.; Zissan, T. Sex differences in prevalence and determinants of hypertension among adults: a cross-sectional survey of one rural village in Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, D.A.; Jones, D.; Textor, S.; Goff, D.C.; Murphy, T.P.; Toto, R.D.; White, A.; Cushman, W.C.; White, W.; et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 2008, 51, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Shin, J.; Ihm, S.H.; Kim, K.I.; Kim, H.L.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, E.M.; Lee, J.H.; Ahn, S.Y.; Cho, E.J.; et al. Resistant hypertension: consensus document from the Korean society of hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Wu, B. The relationship between the age of onset of hypertension and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study of the American population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1426953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, M.J.; Basile, J.N. Review of recent literature in hypertension: Updated clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease now include albuminuria in the classification system. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2013, 15, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulè, G.; Castiglia, A.; Cusumano, C.; Scaduto, E.; Geraci, G.; Altieri, D.; Di Natale, E.; Cacciatore, O.; Cerasola, G.; Cottone, S. Subclinical Kidney Damage in Hypertensive Patients: A Renal Window Opened on the Cardiovascular System. Focus on Microalbuminuria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 279–306. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Pencina, M.J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Palaniappan, L.P.; Sperling, L.S.; Virani, S.S.; Ho, J.E.; et al. Novel Prediction Equations for Absolute Risk Assessment of Total Cardiovascular Disease Incorporating Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1982–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massy, Z.A.; Drueke, T.B. Combination of Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Metabolic Diseases in a Syndrome Named Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic, With New Risk Prediction Equations. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2608–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, A.; Hariri, E.; Ozkan, B.; Lang, K.; Khan, S.S.; Rangaswami, J.; Stone, N.J.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Ndumele, C.E. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Case-Based Narrative Review. Am. J. Med. Open 2025, 13, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zou, Y.; Leng, X.; Huang, F.; Huang, R.; Wijayabahu, A.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y. Associations of blood lead, cadmium, and mercury with resistant hypertension among adults in NHANES, 1999-2018. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2023, 28, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, A.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Associations Between Lead and Cadmium Exposure and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in U.S. Adults. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2025, 25, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Dang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, S.; Ouyang, C.; Shi, X.; Pan, J.; Hu, X. Associations of urinary and blood cadmium concentrations with all-cause mortality in US adults with chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 61659–61671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; Ge, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, L.; Xu, Q. Complex interplay of heavy metals and renal injury: New perspectives from longitudinal epidemiological evidence. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Xin, M.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, Q. Heavy metals and elderly kidney health: A multidimensional study through Enviro-target Mendelian Randomization. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.; Jang, M.; Kim, K. Effect of combined exposure to lead, mercury, and cadmium on hypertension: the 2008-2013 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2025, 203648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeon, J.; Kang, S.; Park, J.; Ahn, J.H.; Cho, E.A.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, K.H.; Shim, J.G. Association between blood cadmium levels and the risk of chronic kidney disease in Korea, based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2016-2017. Asian Biomed. (Res Rev News) 2025, 19, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gburek, J.; Konopska, B.; Gołąb, K. Renal handling of albumin-from early findings to current concepts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzing, T.; Salant, D. Insights into glomerular filtration and albuminuria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitoris, B.A.; Sandoval, R.M.; Yadav, S.P.S.; Wagner, M.C. Albumin uptake and processing by the proximal tubule: Physiological, pathological, and therapeutic implications. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1625–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshbach, M.L.; Weisz, O.A. Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the proximal tubule. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comper, W.D.; Vuchkova, J.; McCarthy, K.J. New insights into proteinuria/albuminuria. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 991756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The pathogenesis of albuminuria in cadmium nephropathy. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Christensen, E.I.; Birn, H. Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: from experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.K.; Thévenod, F. Cell organelles as targets of mammalian cadmium toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1017–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thévenod, F.; Lee, W.K.; Garrick, M.D. Iron and cadmium entry into renal mitochondria: Physiological and toxicological implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Yu, B.; Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Gao, C.; Pan, H.; Han, F.; Lin, W.; et al. STING promotes ferroptosis through NCOA4-dependent ferritinophagy in acute kidney injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasinger, J.H.; Abais-Battad, J.M.; McCrorey, M.K.; Van Beusecum, J.P. Recent advances on immunity and hypertension: the new cells on the kidney block. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2025, 328, F301–F315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gu, X. Emerging roles of proximal tubular endocytosis in renal fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1235716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Yimthiang, S.; Khamphaya, T.; Pouyfung, P.; Vesey, D.A.; Buha Đorđević, A. Albuminuria in People Chronically Exposed to Low-Dose Cadmium Is Linked to Rising Blood Pressure Levels. Toxics 2025, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeme, J.C.; Katz, R.; Muiru, A.N.; Estrella, M.M.; Scherzer, R.; Garimella, P.S.; Hallan, S.I.; Peralta, C.A.; Ix, J.H.; Shlipak, M.G. Clinical Risk Factors For Kidney Tubule Biomarker Abnormalities Among Hypertensive Adults With Reduced eGFR in the SPRINT Trial. Am. J. Hypertens. 2022, 35, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lv, L.L. New Understanding on the Role of Proteinuria in Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1165, 487–500. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Smyth, B. From Proteinuria to Fibrosis: An Update on Pathophysiology and Treatment Options. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2021, 46, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhammajanov, Z.; Gaipov, A.; Myngbay, A.; Bukasov, R.; Aljofan, M.; Kanbay, M. Tubular toxicity of proteinuria and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre, A.; Verissimo, T.; de Seigneux, S. Proteinuria and tubular cells: Plasticity and toxicity. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 2025, 241, e14263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, L.K.; Heine, M.; Thompson, K. 1972. Genetic influence of renal homografts on the blood pressure of rats from different strains. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1972, 140, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, L.K.; Heine, M.; Thompson, K. 1974. Genetic influence of the kidneys on blood pressure: evidence from chronic renal homografts in rats with opposite predispositions to hypertension. Circ. Res. 1974, 34, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, L.K.; Heine, M. Primary role of renal homografts in setting chronic blood pressure levels in rats. Circ. Res. 1975, 36, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyton, A.C. 1991. Blood pressure control-special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science 1991, 252, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, E.J.; Kim, S. Current Understanding of Pressure Natriuresis. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2021, 19, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, R.J. 20-HETE and Hypertension. Hypertension 2024, 81, 2012–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froogh, G.; Garcia, V.; Schwartzman, M.L. The CYP/20-HETE/GPR75 axis in hypertension. Adv. Pharmacol. 2022, 94, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Morales, N.; Baranda-Alonso, E.M.; Martínez-Salgado, C.; López-Hernández, F.J. Renal sympathetic activity: A key modulator of pressure natriuresis in hypertension. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 208, 115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.P.O.; Li, X.C.; Nwia, S.M.; Hassan, R.; Zhuo, J.L. Angiotensin II and AT1a Receptors in the Proximal Tubules of the Kidney: New Roles in Blood Pressure Control and Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasker, J.M.; Chen, W.B.; Wolf, I.; Bloswick, B.P.; Wilson, P.D.; Powell, P.K. Formation of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, a vasoactive and natriuretic eicosanoid, in human kidney. Role of CYP4F2 and CYP4A11. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 4118–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonick, H.C. Pathophysiology of human proximal tubular transport defects. Klin. Wochenschr. 1982, 60, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, L.G.; Schnermann, J. Integrated control of Na transport along the nephron. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartzman, M.L.; Martasek, P.; Rios, A.R.; Levere, R.D.; Solangi, K.; Goodman, A.L.; Abraham, N.G. Cytochrome P450-dependent arachidonic acid metabolism in human kidney. Kidney Int. 1990, 37, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Zhang, J.Y.; Falck, J.R.; Chauman, K.; Blair, A. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is excreted as a glucuronide conjugate in human urine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1992, 158, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonprasert, K.; Satarug, S.; Morais, C.; Gobe, G.C.; Johnson, D.W.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Vesey, D.A. The stress response of human proximal tubule cells to cadmium involves up-regulation of haemoxygenase 1 and metallothionein but not cytochrome P450 enzymes. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 249, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjimaporn, A.; Botsford, T.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, M.A.; Zhou, X.D.; Dunlevy, J.R.; Sens, D.A.; Somji, S. ZIP8 expression in human proximal tubule cells, human urothelial cells transformed by Cd+2 and As+3 and in specimens of normal human urothelium and urothelial cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 12, 16.

- Subramanya, A.R.; Ellison, D.H. Distal convoluted tubule. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014, 9, 2147–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenod, F.; Friedmann, J.M. Cadmium-mediated oxidative stress in kidney proximal tubule cells induces degradation of Na+/K+-ATPase through proteasomal and endo-/lysosomal proteolytic pathways. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Satarug, S.; Urbenjapol, S.; Edwards, R.J.; Williams, D.J.; Moore, M.R.; Reilly, P.E. Associations between human liver and kidney cadmium content and immunochemically detected CYP4A11 apoprotein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 63, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Satarug, S.; Edwards, R.J.; Moore, M.R.; Williams, D.J.; Reilly, P.E. Potential for early involvement of CYP isoforms in aspects of human cadmium toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 137, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.R.; Edwards, R.J.; Lasker, J.M.; Moore, M.R.; Satarug, S. Renal and hepatic accumulation of cadmium and lead in the expression of CYP4F2 and CYP2E1. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 159, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, H.M., Jr.; Erlanger, M.W. Sodium retention in rats with cadmium-induced hypertension. Sci. Total Environ. 1981, 22, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena, A.; Iturri, S.J. 1993. Cadmium as hypertensive agent. Effect on ion excretion in rats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 1993, 106, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, I.; Engström, A.; Vahter, M.; Skerfving, S.; Lundh, T.; Lidfeldt, J.; Samsioe, G.; Halldin, K.; Åkesson, A. Associations between cadmium exposure and circulating levels of sex hormones in postmenopausal women. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, C.; Konishi, K.; Goto, Y.; Tamura, T.; Wada, K.; Hayashi, M.; Takeda, N.; Yasuda, K. Associations of urinary cadmium with circulating sex hormone levels in pre- and postmenopausal Japanese women. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Nagao, Y.; Shibuya, C.; Kashiki, Y.; Shimizu, H. Urinary cadmium and serum levels of estrogens and androgens in postmenopausal Japanese women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Geng, L.; Zhou, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Du, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M. Toxic metals and trace elements, markers of inflammation, and hyperandrogenemia in women and testosterone deficiency in men: Associations and potential mediating factors. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 299, 118352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Schwartzman, M.L. The role of 20-HETE in androgen-mediated hypertension. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 96, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmasso, C.; Maranon, R.; Patil, C.; Moulana, M.; Romero, D.G.; Reckelhoff, J.F. 20-HETE and CYP4A2 ω-hydroxylase contribute to the elevated blood pressure in hyperandrogenemic female rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 311, F71–F77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Garcia, V.; Gilani, A.; Mishra, P.; Zhang, F.F.; Paudyal, M.P.; Falck, J.R.; Nasjletti, A.; Wang, W.H.; Schwartzman, M.L. The Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of 20-HETE Blockade in Cyp4a14(-/-) Mice Is Associated with Natriuresis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 363, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonprasert, K.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Ruenweerayut, R.; Johnson, D.W.; Na-Bangchang, K.; Satarug, S. Is renal tubular cadmium toxicity clinically relevant? Clin. Kidney J. 2018, 11, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee Update: Use of the benchmark dose approach in risk assessment. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 4658.

- Slob, W.; Setzer, R.W. Shape and steepness of toxicological dose-response relationships of continuous endpoints. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slob, W. A general theory of effect size, and its consequences for defining the benchmark response (BMR) for continuous endpoints. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2017, 47, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipsson, A.F.; Sand, S.; Nilsson, J.; Victorin, K. The benchmark dose method--review of available models, and recommendations for application in health risk assessment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2003, 33, 505–542. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, S.J.; von Rosen, D.; Filipsson, A.F. Benchmark calculations in risk assessment using continuous dose-response information: the influence of variance and the determination of a cut-off value. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wei, S.; Wei, Y.; Guo, B.; Yang, M.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X.; Cai, X. The reference dose for subchronic exposure of pigs to cadmium leading to early renal damage by benchmark dose method. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 128, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byber, K.; Lison, D.; Verougstraete, V.; Dressel, H.; Hotz, P. Cadmium or cadmium compounds and chronic kidney disease in workers and the general population: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2016, 46, 191–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, C.; Kazemi, M.; Cheng, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaei, A.; Taheri, E.; Moradi, S. Associations between exposure to heavy metals and the risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, A.B.; Vesey, D.A.; Satarug, S. Cadmium-induced nephrotoxicity assessed by benchmark dose calculations in two exposure-effect datasets. Discover Toxicol. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E. Total imprecision of exposure biomarkers: Implications for calculating exposure limits. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2007, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, K.R.; Gosmanova, E.O. A generic method for analysis of plasma concentrations. Clin. Nephrol. 2020, 94, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, C.P.; Chen, S.S.; Ng, Y.-H.; Roumelioti, M.-E.; Shaffi, K.; Singh, P.P.; Tzamaloukas, A.H. Rediscovering Beta-2 Microglobulin as a Biomarker across the Spectrum of Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivanathan, P.C.; Ooi, K.S.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Ahmadipour, M.; Dee, C.F.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Hamzah, A.A.; Chang, E.Y. Lifting the Veil: Characteristics, Clinical Significance, and Application of β-2-Microglobulin as Biomarkers and Its Detection with Biosensors. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 3142–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Phelps, K.R. Cadmium exposure and toxicity. In: Bagchi D, Bagchi M, eds: Metal Toxicology Handbook, Ch 14, pp 219-272. New York, CRC Press, 2021.

- Phelps, K.R.; Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Vesey, D.A.; Satarug, S. Homeostasis of β2-Microglobulin in Diabetics and Non-Diabetics with Modest Cadmium Intoxication. [CrossRef]

- Mashima, Y.; Konta, T.; Kudo, K.; Takasaki, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Suzuki, K.; Shibata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kato, T.; Kawata, S.; et al. Increases in urinary albumin and beta2-microglobulin are independently associated with blood pressure in the Japanese general population: The Takahata Study. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 34, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, M.; Wai, K.M.; Kanda, A.; Ando, M.; Murashita, K.; Nakaji, S.; Ihara, K. Low Level of Serum Cadmium in Relation to Blood Pressures Among Japanese General Population. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Satarug, S. Evidence Linking Cadmium Exposure and β2-Microglobulin to Increased Risk of Hypertension in Diabetes Type 2. Toxics 2023, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S. Urinary β2-Microglobulin Predicts the Risk of Hypertension in Populations Chronically Exposed to Environmental Cadmium. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, T.; Meng, Q.; Saleh, M.A.; Norlander, A.E.; Joehanes, R.; Zhu, J.; Chen, B.H.; Zhang, B.; Johnson, A.D.; Ying, S.; et al. Integrative network analysis reveals molecular mechanisms of blood pressure regulation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Hank, S.; Dale, B.L.; Himmel, L.; Zhong, X.; Smart, C.D.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Prabakaran, N.; Tirado, B.; et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in SH2B3/LNK promotes hypertension development and renal damage. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, J.A.; Hwang, S.J.; Huan, T.; Mendelson, M.; Yao, C.; Courchesne, P.; Saleh, M.A.; Madhur, M.S.; Levy, D. Evidence for a causal role of the SH2B3-β2M axis in blood pressure regulation. Hypertension 2019, 73, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Đorđević, A.B. The NOAEL equivalent for the cumulative body burden of cadmium: Focus on proteinuria as an endpoint. J. Environ. Expo. Assess. 2024, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Li, M.; Xu, H.; Qin, X.; Teng, Y. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio within the normal range and risk of hypertension in the general population: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, A.; Nakashima, A.; Doi, S.; Doi, T.; Ueno, T.; Maeda, K.; Tamura, R.; Yamane, K.; Masaki, T. High-normal albuminuria is strongly associated with incident chronic kidney disease in a nondiabetic population with normal range of albuminuria and normal kidney function. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2020, 24, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, L.; Liao, Y.; Wu, B.; et al. Elevated urine albumin creatinine ratio increases cardiovascular mortality in coronary artery disease patients with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multicenter retrospective study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GFR domain | Albuminuria domain |

|---|---|

| G1: Normal or high eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

A1: Normal to mildly increased AER < 30 mg/d or ACR <30 mg albumin/g creatinine |

| G2: Mildly decreased eGFR 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

A2: Moderately increased AER 30–300 mg/d or ACR 30–300 mg/g creatinine |

| G3a: Mildly to moderately decreased eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 G3b: Moderately to severely decreased eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

A3: Severely increased AER > 300 mg/d or ACR >300 mg/g creatinine |

| G4: Severely decreased eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|

| G5: Kidney failure eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Study Population | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NHANES, 1999-2018 n = 38,281, 3.7% resistance hypertension, 27.6% hypertension. |

Risk for resistant hypertension rose 30 and 35% comparing blood Cd in quartiles 3 and 4, with blood Cd in the bottom quartile, respectively. | Chen et al. 2023 [58] |

| NHANES 1999-2004, n = 10,197, ≥ 20 years |

Risk for plasma levels of cardiac troponin (cTnT) ≥ 19 ng/L and of N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) ≥ 125 pg/mL rose 33 and 39% at blood Cd concentration ≥ 1.0 μg/L | Liu et al. 2025 [59] |

| NHANES 1999–2014 CKD cohort, n =1825, Follow-up period, 6.8 years |

Risk for all-cause mortality rose 75 and 59% at Cd excretion rates ≥ 0.60 μg/g creatinine, and blood Cd concentrations ≥ 0.70 μg/L, respectively. | Zhang et al. 2023 [60] |

| Northeast China n = 384, four-time repeated measurements, 2016-2021 |

Cd and Cr produced synergistic effects on NAG excretion, albuminuria, and ACR Cd and Pb produced synergistic effects on NAG excretion and ACR. |

Yin et al. 2024 [61] |

| Jinzhou, Liaoning, China, n = 529, three-time repeated measurements of Cd, Cr and Pb excretion rates and effects on kidneys. 2016–2021. |

Baseline median values for urine Cd, Cr, and Pb were 2.41, 3.96 and 2.49 μg/L, respectively. Baseline median values for urine NAG, β2M, Alb, ACR, and eGFR were 8.86 U/L, 790 µg/L, 24.4 mg/L, 21.2 mg/g creatinine, and 102 mL/min/1.73 m², respectively, A combined exposure to Cd, Cr and Pb caused more extensive injury to kidneys than did each individual metal. |

Yin et al. 2024 [62] |

| Korean NHANES 2008-2013 n = 40,328, GM for blood Pb and blood Cd in males (females) were 2.5 (1.84) µg/dL and 0.88 (1.04) µg/L. |

Increment in risk for hypertension by 29, 47 and 78% were associated with Pb, Cd and a combined Cd and Pb exposure, respectively. | Kim et al. 2025 [63] |

| Korean NHANES 2016-2017 n = 4,222, ≥ 30 years, 5.1% had CKD. Mean blood Cd 1.2 µg/L. |

A 2.70-fold increase in risk for CKD was associated blood Cd in those who had hypertension. A 2.40-fold increase in risk for CKD was associated with blood Cd in non-diabetics. |

Yeon et al. 2025 [64] |

| a CKD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | POR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 1.173 | 1.128 | 1.220 | <0.001 | |

| Log2[(ECd/Ecr) × 103], µg/g creatinine | 1.981 | 1.500 | 2.615 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 1.135 | 0.533 | 2.415 | 0.743 | |

| Hypertension | 1.933 | 0.965 | 3.874 | 0.063 | |

| Smoking | 1.140 | 0.529 | 2.456 | 0.738 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| 12–18 | Referent | ||||

| 19–23 | 1.150 | 0.441 | 3.002 | 0.775 | |

| ≥ 24 | 4.002 | 1.351 | 11.86 | 0.012 | |

| Model B | POR | Lower | Upper | p | |

| Age | 1.168 | 1.119 | 1.219 | <0.001 | |

| Log2[(ECd/Ccr) × 105], µg/L filtrate | 3.132 | 2.249 | 4.361 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | 0.719 | 0.315 | 1.643 | 0.434 | |

| Hypertension | 2.656 | 1.231 | 5.727 | 0.013 | |

| Smoking | 1.103 | 0.487 | 2.495 | 0.815 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| 12–18 | Referent | ||||

| 19–23 | 1.134 | 0.403 | 3.189 | 0.812 | |

| ≥ 24 | 4.784 | 1.468 | 15.59 | 0.009 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).