1. Introduction

X-rays are the most common imaging technique used in medical diagnostics due to their widespread availability, speed, and cost-effectiveness [

1]. Specifically, chest X-rays (CXRs) are useful diagnostic imaging modalities in clinical practice, which aid medical professionals in detecting and monitoring of a wide range of thoracic diseases. Interpreting these images, however, requires radiological expertise and time, and remains susceptible to inter-reader variability [

2].

In addition to this, the high volume of CXR studies contributes to raising a radiologist workload [

3], increasing the risk of reporting delays and potential oversights, particularly for subtle findings. In resource-limited locations, the shortage of specialized radiologists further complicates timely and accurate diagnoses. These challenges indicate the need for improved solutions to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility of CXR medical report generation [

4].

To address these challenges, Deep learning systems learn to recognize patterns in medical images, helping detect pathologies like lung and heart diseases [

5]. Instead of relying solely on human experts, the technology can quickly analyze a large volume of X-rays, flagging potential issues for physicians to review.

It is, however, important that the AI can also highlight the concerning areas on the image, making it easier for medical professionals to understand its findings, enhancing the clearer communication between the AI system and medical professionals and strengthening the trust in the model. [

6]

Despite the progress in AI-driven CXR interpretation, existing solutions often lack a full integration of visual explanation, anatomical relevance, and structured report generation, limiting their clinical adoption.

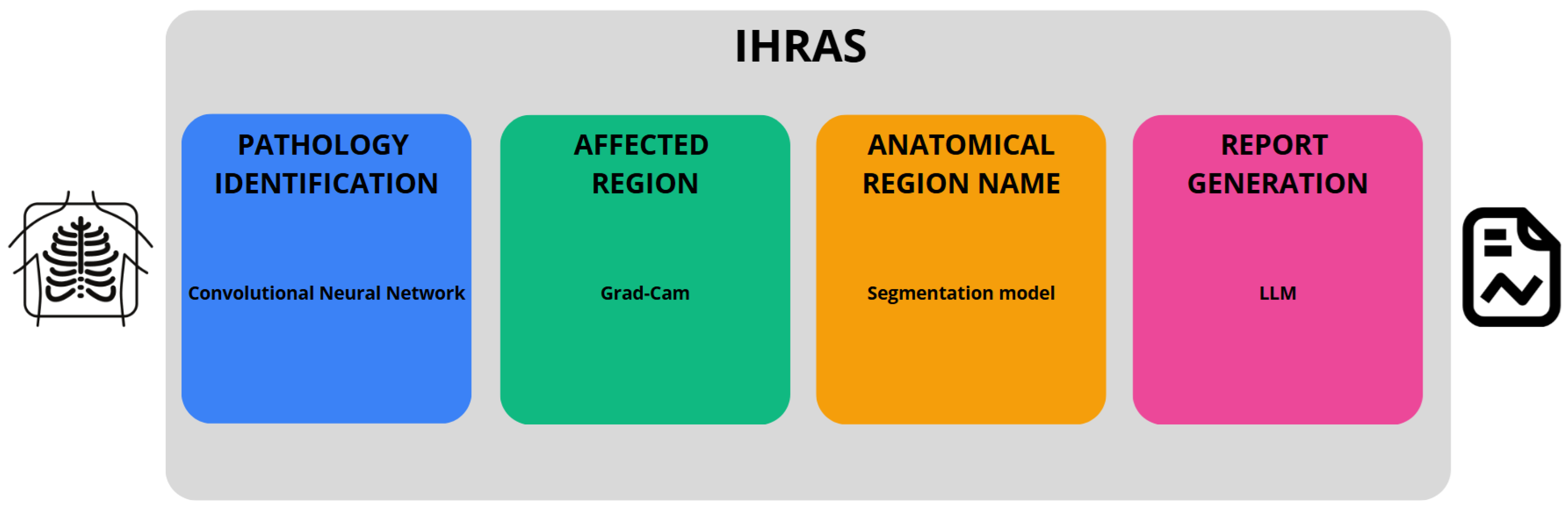

In this study, we introduce the Intelligent Humanized Radiology Analysis System (IHRAS), a modular architecture designed to overcome limitations in chest X-ray interpretation. IHRAS seamlessly integrates disease classification, visual explanation, anatomical segmentation, and automated medical report generation. Upon receiving a chest X-ray image, the system classifies it into 14 common thoracic diseases using a deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). To enhance interpretability, it leverages Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to highlight the spatial regions most relevant to the identified conditions. To enhance interpretability, we further segment these regions using a dedicated anatomical segmentation model, assigning them to clinically relevant anatomical structures. Ultimately, these findings are used to condition a Large Language Model (LLM) that generates a human-readable medical report using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT). IHRAS is tested on the NIH

While IHRAS demonstrates the possibility of automating radiological workflows, auditability is necessary to maintain accountability. The system’s decisions must be interpretable and traceable to allow clinicians to validate and understand AI outputs, mitigating the risk of over-reliance on automated systems.

Another consideration is the generalizability of the proposed system across diverse populations and imaging conditions. CXR datasets often reflect demographic and geographic biases that may lead to suboptimal performance in underrepresented groups [

7]. Therefore, comprehensive evaluation across multi-institutional datasets with diverse patient profiles is necessary to ensure consistent performance.

1.1. Contributions and Limitations of the Work

The primary contributions of this work lie in the development of a modular architecture for automated chest X-ray report generation that unifies classification, localization, segmentation, and language modeling. The system utilizes Grad-CAM to produce visual explanations of disease predictions, which are further enhanced by anatomical context through segmentation, thereby improving both interpretability and clinical relevance. This integrated framework represents a significant step forward in radiological image analysis and report generation.

Unlike prior architectures, IHRAS integrates classification, spatial reasoning, anatomical segmentation, and structured language modeling into a unified pipeline, thus providing a more complete approach.

Due to its modular nature, IHRAS may be adapted to generate medical reports beyond CXR, including X-rays of other body parts, such as abdomen and head, as well as other imaging modalities, such as blood cell microscopy and ocular imaging.

As limitation, the pretrained model achieved a modest F1-score for the multilabel classification problem, which, while comparable to other generalist models in the literature, reflects the challenge of diagnosing diverse pathologies simultaneously.

Furthermore, although IHRAS employs Grad-CAM visualizations to provide interpretable predictions, the lack of pixel-level annotations in the dataset prevents quantitative validation of the highlighted regions. Consequently, the accuracy of the attention maps cannot be formally assessed.

1.2. Organization of the Work

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related literature.

Section 3 presents the proposed modular architecture of IHRAS, whilst

Section 4 discusses the results obtained with the approach.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

Due to the significant relevance and growing demand for advancements in chest and general X-ray research, several datasets have been published to support studies in this field [

8], including in specific regions, such as in Brazil [

9]. These datasets facilitate the development and validation of machine learning models, diagnostic tools, and other medical imaging applications.

Using such datasets, CNNs and transformer-based architectures have demonstrated high accuracy in detecting medical conditions such as lung cancer, tuberculosis and COVID-19 [

10]. Our work assesses different CNN models with the NIH CXR dataset, selecting the model and its parameters that optimize the classification metrics to generate medical reports.

As an example, [

11] have achieved a F1-score of 0.937 and of 0.954 in different datasets for the detection of pneumonia using VGG-16 with Neural Networks. These results are significant due to the clinical importance of rapid and accurate detection of this infection, which represents a significant cause of hospitalization worldwide.

Deep Learning models are applicable in several healthcare domains beyond the scope of X-ray images. For instance, [

12] presented a deep transfer learning framework for the automated classification of leukemia subtypes using microscopic peripheral blood smear images. They used a dataset comprising 1250 images across five categories of the disease, with feature extraction performed via fine-tuned VGG16 and classification using Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest. Despite achieving an accuracy of 84%, the study did not employ anatomical segmentation or language-based report generation. In contrast, our proposed IHRAS system inegrates pathology classification with anatomical segmentation and natural language report generation, enhancing clinical utility.

In addition to an accurate pathology classification, [

13] indicate that an explainable Artificial Intelligence (AI) enhances the transparency, reliability, and safety of diagnostic systems, contributing to improved healthcare delivery. Because of this, IHRAS adopts Grad-CAM, which provides interpretable visual explanations of model decisions, allowing clinicians to understand the AI’s reasoning for the detected abnormalities.

Recent work has explored adapting LLMs to healthcare, where general-purpose models often struggle due to terminology gaps and limited task-specific training data. MedChatZH [

14] proposed a decoder-based model trained on a curated corpus of Traditional Chinese Medicine literature, demonstrating improved performance over generic dialogue baselines, aligning with broader efforts to tailor LLMs for expert domains through targeted data augmentation and architecture adaptation. Their work highlights the effectiveness of LLMs in medical applications. Therefore, in this paper, we use LLM to generate structured medical reports using the SNOMED CT standardized terminology system.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to combine classification, explainability, segmentation and medical report generation with LLM in the same architecture, as depicted in

Table 1.

3. Methodology

The dataset used in this work is the NIH Chest X-ray collection [

21], chosen for its large scale, multi-label annotations corresponding to 14 thoracic pathologies, and open accessibility, which enables reproducible evaluation of IHRAS’s performance in chest X-ray analysis. Our proposed architecture, developed in Python version 3.11.12, is depicted in

Figure 1, encompassing from the input of a CXR image to the generation of the medical report.

3.1. Pathology Classification

Each inputted X-ray image may be classified as according to different pathologies, namely atelectasis, cardiomegaly, consolidation, edema, effusion, emphysema, fibrosis, hernia, infiltration, mass, nodule, pleural thickening, pneumonia, and pneumothorax. It is a multi label classification problem, that is, each image can be associated with multiple labels simultaneously.

Three pretrained deep learning models are evaluated, and the best performing model is selected for integration into the IHRAS framework, to ensure optimal diagnostic accuracy. These models are obtained from TorchXRayVision [

22], and refer to a Dense Convolutional Network (DenseNet) [

23] trained on several CXR datasets; a DenseNet trained specifically on the NIH dataset; and a Deep Residual Learning model (ResNet) [

24] trained on several chest X-ray datasets. These models are selected due to their high accuracy in pathology classification [

25].

These models are evaluated based on some metrics. The first one is precision, which measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive instances among all predicted positives, as according to Equation

1, where

,

,

, and

denote True Positives, False Positives, True Negatives, and False Negatives respectively. This metrics should be considered when the cost of false positives is high.

Recall, also known as sensitivity and defined by Equation

2, quantifies the ability to identify true positives. It is a relevant metric when missing positive cases is undesirable.

The F1-score, determined by Equation

3, represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Ultimately, specificity, calculated as in Equation

4, measures the ability to identify negative instances.

3.1.1. Dataset Sampling

To reduce computational costs and processing time while maintaining a representative sample of the dataset for the models comparison, we employed a stratified random sampling strategy. The population was partitioned into homogeneous strata based on four clinically relevant variables: (i) patient age (grouped into 25-year intervals); (ii) radiological findings; (iii) patient gender; and (iv) radiographic view position.

The sample size per stratum is determined based on Equation

5, in which

Z represents the Z-score, corresponding to the desired confidence level;

p denotes the estimated proportion; and

e stands for the margin of error. The variable

n represents the sample size, whereas

N is the population size.

We selected 370 samples per stratum to achieve a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error for the largest strata (). This stratified sampling approach preserves the original dataset’s clinical and demographic diversity. This results in a total of 50,133 selected X-ray images.

3.2. Affected Region and Its Anatomical Name

Since medical reports need to have clarity, Grad-CAM is used to enhance explainability, as it has been demonstrated to improve the interpretability of deep learning models in medical imaging [

26]. This technique generates heatmaps that indicate the regions of the image that most strongly influenced the model’s diagnostic conclusions. This spatial alignment with radiological markers allows clinicians to audit whether the model’s decisions are anatomically plausible, complying with requirements for transparency in medical AI.

To further enhance the interpretability of the model’s decisions, a segmentation model is employed to identify the anatomical name of the regions highlighted by Grad-CAM. This ensures adherence to standardized medical reporting, as the medical report references meaningful structures rather than relying on generic image coordinates or non-clinical descriptors.

To achieve this segmentation, we use the Structure-Aware Relation Network (SAR-Net) model proposed by [

27]. The SAR-Net model is evaluated on ChestX-Det, which is a subset of the NIH dataset, used in this work, achieving a Mean Intersection-Over-Union of 86.85%. The anatomical structures it is trained to identify are the aorta, facies diaphragmatica, heart, left clavicle, left hilus pulmonis, left lung, left scapula, mediastinum, right clavicle, right hilus pulmonis, right lung, right scapula, spine, and weasand.

3.3. Report Generation

The extracted diagnostic data, comprising identified pathologies with associated probabilities and affected anatomical regions, alongside supplementary inputs such as patient demographics (age, gender) and radiographic projection, is processed by an LLM to generate a medical report. This approach provides a patient-aware report generation.

To select the LLM model for this task, we considered the BRIDGE benchmark, that is composed of 87 tasks based on clinical data from real-world sources, covering nine languages [

28]. The authors compared a total of 52 different LLMs using multiple inference approaches, and DeepSeek-R1 achieved the highest score in radiology and ranks among the top 3 in the overall score, along with Gemini-1.5-Pro and GPT-4o. These general-purposed models achieved even better results than the medically fine-tuned ones. Because of these results, we use DeepSeek-R1 to generate the radiological report [

29].

The report generation employs the CRISPE framework (Capacity, Role, Insight, Statement, Personality, Experiment) for structured prompt engineering, which enhances the LLM’s output quality [

30]. This methodology ensures precise instruction by (C) defining the model’s clinical expertise boundaries; (R) establishing a radiologist role; (I) incorporating patient-specific contextual data and diagnosis; (S) specifying reporting requirements with SNOMED CT compliance; (P) maintaining professional tone consistency; and (E) limiting . The structure prompt following this framework is shown in

Table 2.

SNOMED CT enhances this architecture with the standardization of clinical terminology, improving data quality through consistent indexing, and with the advance of the continuity of care through interoperable patient records. It also facilitates clinical research with a structured data aggregation, and improves patient safety [

31]. Due to these benefits, the LLM is instructed to use SNOMED CT.

To evaluate the quality of the generated medical reports, we employed DeepEval [

32], an open-source framework for assessing LLM outputs using an LLM-as-a-judge approach. The metrics considered in the assessment are faithfulness, to evaluate whether the generated report is aligned with the findings from the previous IHRAS steps; answer relevancy, to measure how relevant the report is in relation to the prompt; hallucination to detect unsupported claims; toxicity and bias, to identify harmful or discriminatory language; and prompt alignment to assess adherence to the CRISPE-structured instructions.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results obtained with the IHRAS pipeline, from the CXR image input up to the report generation.

4.1. Classification Models Evaluation

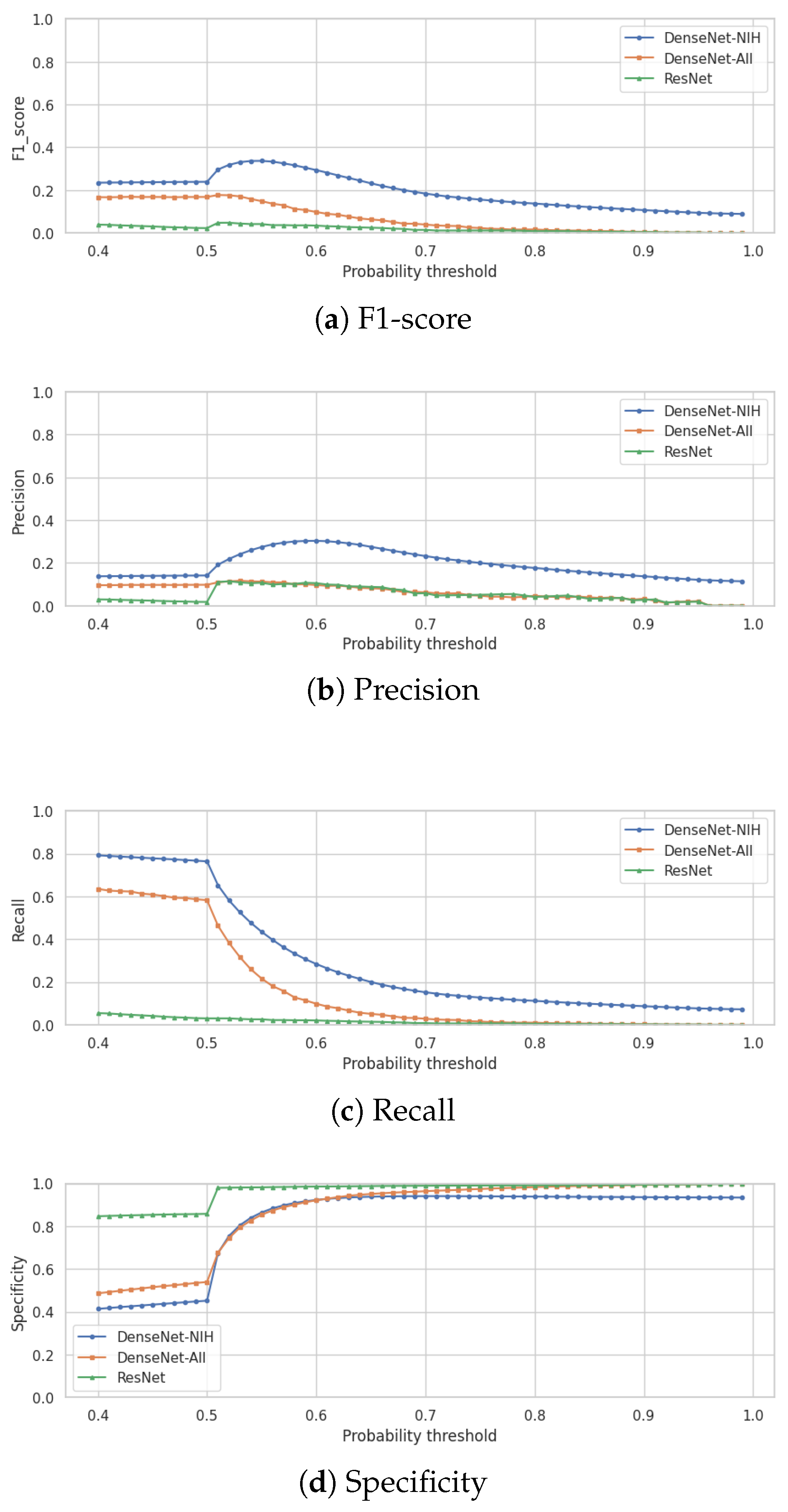

For the disease classification module, we evaluate three models, namely a DenseNet trained on multiple CXR datasets, a DenseNet fine-tuned specifically on the NIH dataset, and a ResNet trained across diverse CXR datasets. The best-performing model, based on evaluation metrics, is selected for integration into IHRAS.

4.1.1. Models Comparison

All evaluated models generate a probability score for each detectable pathology in the input X-ray image. To convert these continuous predictions into binary classifications (present/absent), an optimal decision threshold must be established.

Figure 2 presents the variation of the F1-score (

Figure 2a), of the precision (

Figure 2b), of the recall (

Figure 2c) and of the specificity (

Figure 2d) in function to the variation of this threshold for the three classification models. It is noted that the DenseNet trained specifically for the NIH dataset achieves the best F1-score, precision and recall for a given threshold, and, thus, this model is selected for the classification module of IHRAS in this work.

In this study, we employ the F1-score as our primary optimization metric, to balance false positives and false negatives. As seen in

Figure 2a, the optimal decision threshold of 0.55 maximizes the F1-score at 0.34. This threshold reflects a balance of clinical priorities, equitably weighting sensitivity (to avoid missed diagnoses) and precision (to reduce false alarms). The obtained F1-score is comparable to those of other multilabel classification models evaluated on the same dataset [

33,

34].

In scenarios where false negatives incur higher costs, the threshold should be lowered to prioritize recall, ensuring fewer missed cases. Conversely, when false positives are more detrimental, the threshold should be raised to maximize precision.

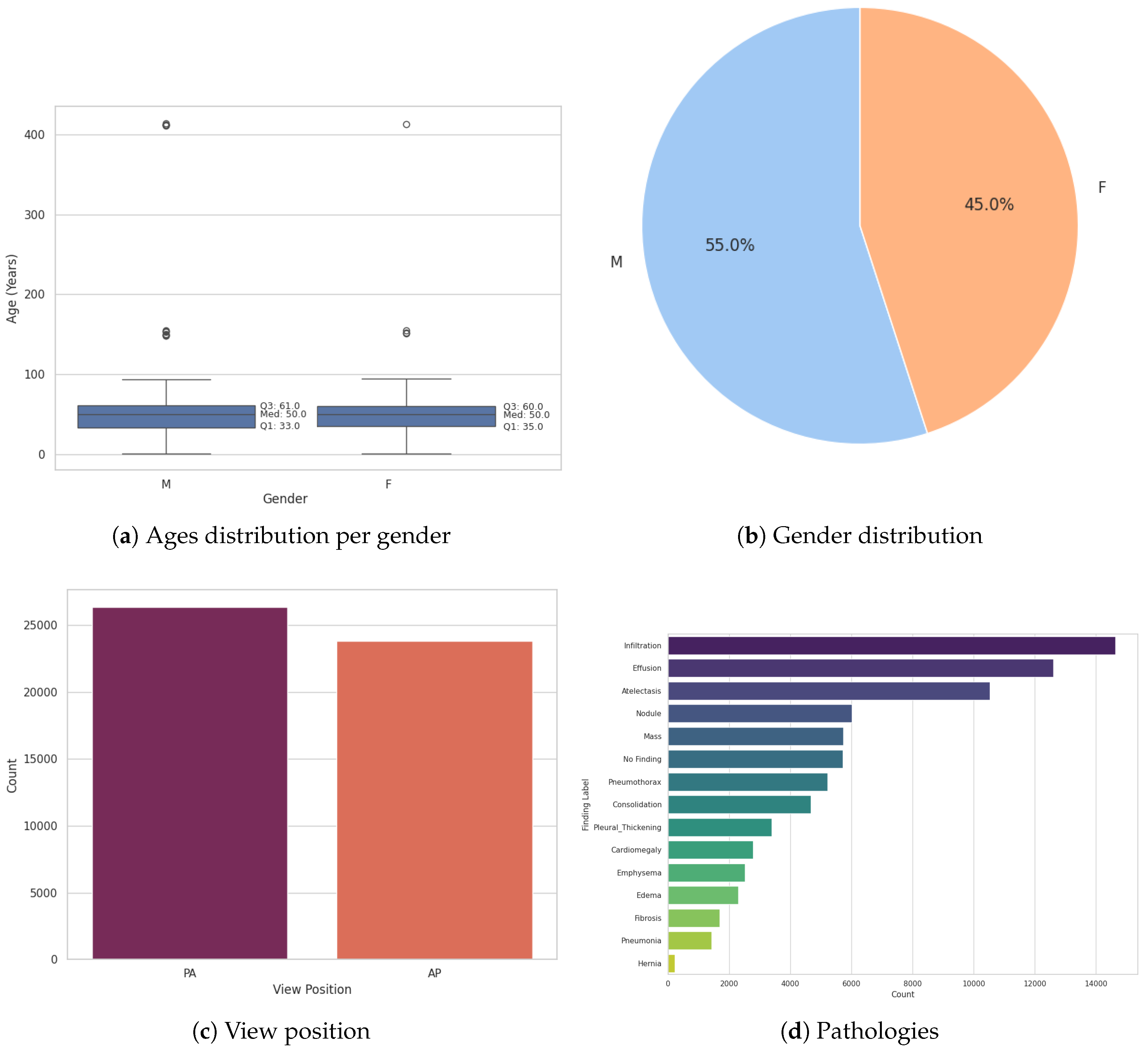

4.1.2. Sample Demographics

It has been observed by [

7] that AI models underdiagnose pathologies in marginalized groups, concluding that there is a significant disparity when comparing "black female" patients with "white male". To assess this disparity within the 0.55 threshold DenseNet model adopted by IHRAS, the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sampled dataset are presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3a reveals apparent anomalies in the age data, including patients recorded as over 400 years old. The median age for both genders, however, is 50 years, suggesting these extreme outliers are likely artifacts of data entry errors rather than representative of the true distribution. The sampled dataset also contains slightly more males than females (

Figure 3b) and Postero-Anterior (PA) views than Antero-Posterior (AP) (

Figure 3c).

Figure 3d show that the imbalance for the pathologies count is significantly greater. However, since this section focuses on assessing a pretrained model’s diagnostic performance across diverse subgroups, rather than training a new model, such imbalances reflect clinical variability rather than methodological limitations.

The comparison of the evaluation metrics for these different demographics and clinical characteristics is presented in

Table 3, which indicates no significant disparities between different demographic and clinical groups.

4.2. Report Generation Evaluation

The metrics associated to the generated medical reports are presented in

Table 4. This assessment assesses the LLM’s ability to generate accurate reports based on the classification results and on the identified affected anatomical region provided to it, rather than comparing against the actual annotated pathology. The performance of the disease classification model has been validated in

Section 4.1.

Instead, this analysis tests the LLM’s capacity to faithfully translate input clinical data into coherent reports, to maintain contextual relevance, and to adhere to clinical reporting standards.

The results shown in

Table 4 demonstrate capabilities for safe clinical deployment. They indicate that the IHRAS LLM module is capable of operating within the healthcare workflow, where accuracy, safety, and consistency are fundamental.

The faithfulness scores validate that reports accurately reflect diagnostic inputs, ensuring reliability in communicating critical findings, which is a fundamental requirement for medical decision-making. The strong performance in answer relevancy indicates that the reports have successfully fulfilled the prompt, while perfect hallucination, toxicity, and bias scores confirm the absence of fabricated claims and harmful content, addressing patient safety and ethical concerns. The prompt alignment results, though slightly lower than other metrics, still reflect robust adherence to structured clinical reporting standards.

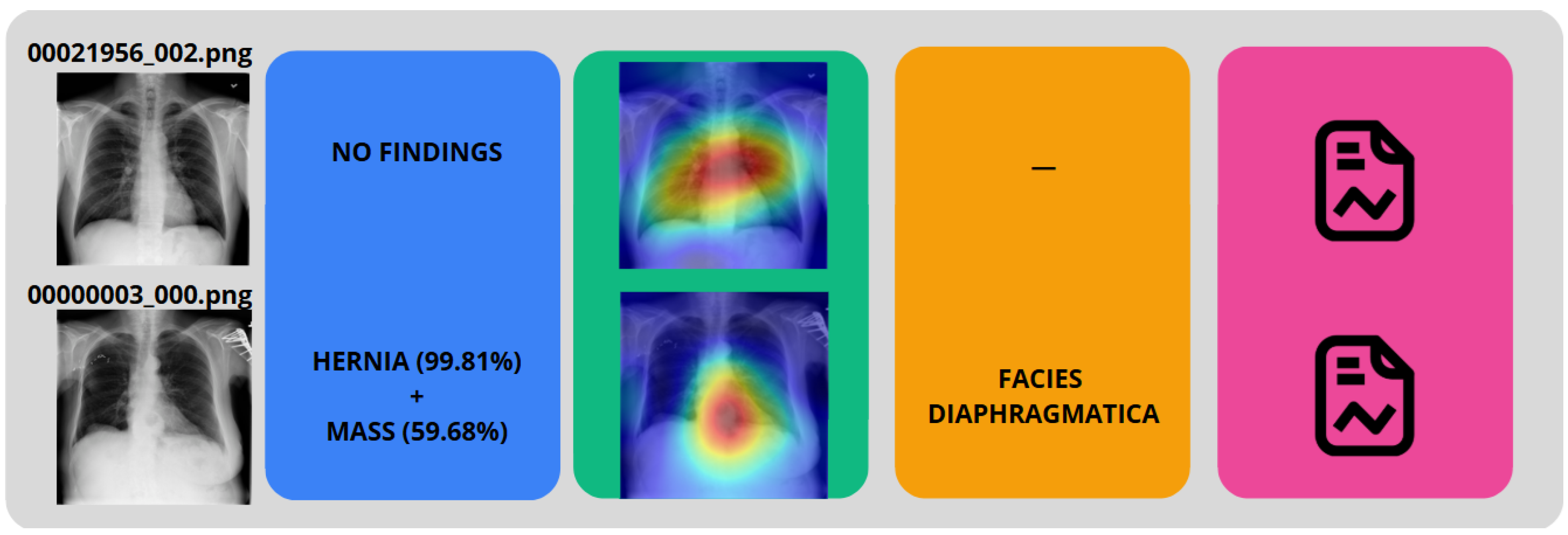

4.3. IHRAS Case Studies

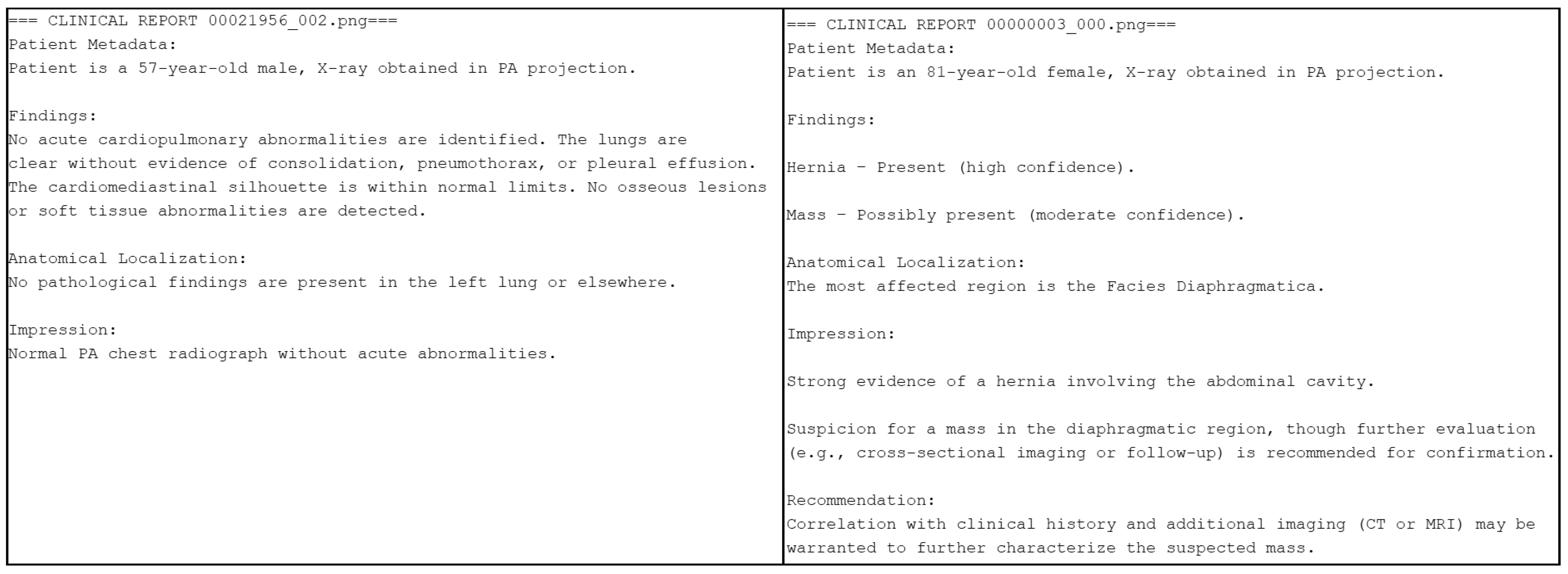

To demonstrate the IHRAS workflow,

Figure 4 depicts two example CXR images from the NIH dataset inputted into the system, with the generated reports presented in

Figure 5.

The CXR 00021956_002.png is correclty classified as a healthy image, whereas it wrongly attributes a mass diagnosis for 00000003_000.png, although the hernia is correctly identified.

5. Conclusion

This work introduced IHRAS, a modular and integrated system designed to enhance the automation and interpretability of chest X-ray analysis by combining disease classification, visual explainability, anatomical segmentation, and structured medical report generation via Large Language Models. IHRAS identifies thoracic pathologies with associated anatomical relevance and produces clinically coherent reports adhering to SNOMED CT standards.

The system demonstrated robust performance across demographic and clinical subgroups in the NIH ChestX-ray dataset, indicating its potential for equitable clinical deployment. The integration of Grad-CAM for visual explanations and SAR-Net for anatomical localization contributes significantly to transparency and trust in AI-driven radiology.

However, the system’s performance is currently constrained by limitations inherent in the training data, including the modest F1-score in the multi-label classification task. Hence, as future work, this module of the IHRAS architecture should be further studied, with the aim of improving its performance. Future works should also investigate the use of the proposed architecture in other medical imaging applications, such as Computed Tomography scans, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and ultrasound, or to other anatomical regions beyond the thorax.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, A.L.M.S. and V.P.G.; validation, supervision, writing—review and editing, G.P.R.F. and R.I.M; methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization G.A.P.R and G.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

This work uses a publicly available dataset.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of the University of Brasília.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AP |

Antero-Posterior |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CXR |

Chest X-Ray |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| DenseNet |

Dense Convolutional Network |

| IHRAS |

Intelligent Humanized Radiology Analysis System |

| PA |

Postero-Anterior |

| ResNet |

a Deep Residual Learning Network |

| SAR-Net |

Structure-Aware Relation Network |

| SNOMED CT |

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

References

- Akhter, Y.; Singh, R.; Vatsa, M. AI-based radiodiagnosis using chest X-rays: A review. Frontiers in big data 2023, 6, 1120989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, P.; Awwad, D.A.; Lewis, S.; Reed, W.; Ekpo, E. Inter-rater concordance in the classification of COVID-19 in chest X-ray images using the RANZCR template for COVID-19 infection. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 2025, 56, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsman, C.D.; Barash, Y.; Klang, E.; Guranda, L.; Konen, E.; Tau, N. Trend in radiologist workload compared to number of admissions in the emergency department. European Journal of Radiology 2022, 149, 110195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanni, S.C.; Marcucci, A.; Volpi, F.; Valentino, S.; Neri, E.; Romei, C. Artificial intelligence-based software with CE mark for chest X-ray interpretation: Opportunities and challenges. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çallı, E.; Sogancioglu, E.; van Ginneken, B.; van Leeuwen, K.G.; Murphy, K. Deep learning for chest X-ray analysis: A survey. Medical image analysis 2021, 72, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, R.; Gour, M.; Jain, S.; Semwal, V.B. Integrated ensemble CNN and explainable AI for COVID-19 diagnosis from CT scan and X-ray images. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 24985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gulhane, A.; Mastrodicasa, D.; Wu, W.; Wang, E.J.; Sahani, D.; Patel, S. Demographic bias of expert-level vision-language foundation models in medical imaging. Science Advances 2025, 11, eadq0305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, G.; Hua, C.; Feng, M.; Bennamoun, B.; Li, P.; Lu, X.; Song, J.; Shen, P.; Xu, X.; et al. A systematic collection of medical image datasets for deep learning. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 56, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, E.P.; De Paiva, J.P.; Da Silva, M.C.; Ribeiro, G.A.; Paiva, V.F.; Bulgarelli, L.; Lee, H.M.; Santos, P.V.; Brito, V.M.; Amaral, L.T.; et al. BRAX, Brazilian labeled chest x-ray dataset. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Anees, T.; Din, M.; Naeem, A. CDC_Net: Multi-classification convolutional neural network model for detection of COVID-19, pneumothorax, pneumonia, lung Cancer, and tuberculosis using chest X-rays. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 13855–13880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Guleria, K. A deep learning based model for the detection of pneumonia from chest X-ray images using VGG-16 and neural networks. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, A.; Jha, R.K.; Sinha, R.; Jha, K. Automated detection and classification of leukemia on a subject-independent test dataset using deep transfer learning supported by Grad-CAM visualization. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 83, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Li, L.; Xin, Z.; Xiang, D.; Huang, J.; Zhou, H.; Shi, F.; Zhu, W.; Cai, J.; Peng, T.; et al. A literature review of artificial intelligence (AI) for medical image segmentation: from AI and explainable AI to trustworthy AI. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 2024, 14, 9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Pan, F.; Duan, H.; Huang, Z.; Deng, H.; Yu, Z.; Yang, C.; Shen, G.; et al. MedChatZH: A tuning LLM for traditional Chinese medicine consultations. Computers in biology and medicine 2024, 172, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmed, F.; Baothman, F.; Alqahtani, F.; Alian, M.; Ahmad, J. Detection of COVID-19 using transfer learning and Grad-CAM visualization on indigenously collected X-ray dataset. Sensors 2021, 21, 5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, A.; Nair, T.R.; Mehta, S.; Prakasam, P. Automatic lung parenchyma segmentation using a deep convolutional neural network from chest X-rays. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 73, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufel, J.; Bielówka, M.; Rojek, M.; Mitręga, A.; Lewandowski, P.; Cebula, M.; Krawczyk, D.; Bielówka, M.; Kondoł, D.; Bargieł-ączek, K.; et al. Multi-label classification of chest X-ray abnormalities using transfer learning techniques. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, A.; Dowling, J.; Koopman, B. Improving chest X-ray report generation by leveraging warm starting. Artificial intelligence in medicine 2023, 144, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Sikka, G.; Swaraj, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A. Classification of COVID-19 on Chest X-Ray Images Using Deep Learning Model with Histogram Equalization and Lung Segmentation. SN Computer Science 2024, 5, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirik, E.; Osman, O.; Esen, V. Exploring the Impact of CLAHE Processing on Disease Classes ‘Effusion,’‘Infiltration,’‘Atelectasis,’and ‘Mass’ in the NIH Chest XRay Dataset Using VGG16 and ResNet50 Architectures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Forthcoming Networks and Sustainability in the AIoT Era. Springer; 2024; pp. 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Lu, Z.; Bagheri, M.; Summers, R.M. Chestx-ray8: Hospital-scale chest x-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp.2097–2106.

- Cohen, J.P.; Viviano, J.D.; Bertin, P.; Morrison, P.; Torabian, P.; Guarrera, M.; Lungren, M.P.; Chaudhari, A.; Brooks, R.; Hashir, M.; et al. TorchXRayVision: A library of chest X-ray datasets and models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Swapnarekha, H.; Behera, H.S.; Nayak, J.; Naik, B. Deep DenseNet and ResNet Approach for COVID-19 Prognosis: Experiments on Real CT Images. In Proceedings of the Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition; Das, A.K.; Nayak, J.; Naik, B.; Dutta, S.; Pelusi, D., Eds., Singapore, 2022; pp. 731–747.

- Suara, S.; Jha, A.; Sinha, P.; Sekh, A.A. Is grad-cam explainable in medical images? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing. Springer; 2023; pp. 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Gao, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Y. A Structure-Aware Relation Network for Thoracic Diseases Detection and Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021, 40, 2042–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gu, B.; Zhou, R.; Xie, K.; Snyder, D.; Jiang, Y.; Carducci, V.; Wyss, R.; Desai, R.J.; Alsentzer, E.; et al. BRIDGE: Benchmarking Large Language Models for Understanding Real-world Clinical Practice Text. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs.CL/2504.19467]. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2501.12948.2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yu, J. Leveraging large language model to generate a novel metaheuristic algorithm with CRISPE framework. Cluster Computing 2024, 27, 13835–13869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuokko, R.; Vakkuri, A.; Palojoki, S. Systematized nomenclature of medicine–clinical terminology (SNOMED CT) clinical use cases in the context of electronic health record systems: systematic literature review. JMIR medical informatics 2023, 11, e43750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, R.; Liu, Q. Beyond static datasets: A deep interaction approach to llm evaluation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2309.04369 2023.

- Hayat, N.; Lashen, H.; Shamout, F.E. Multi-label generalized zero shot learning for the classification of disease in chest radiographs. In Proceedings of the Machine learning for healthcare conference. PMLR; 2021; pp. 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Santomartino, S.M.; Hafezi-Nejad, N.; Parekh, V.S.; Yi, P.H. Performance and usability of code-free deep learning for chest radiograph classification, object detection, and segmentation. Radiology: Artificial Intelligence 2023, 5, e220062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).