Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

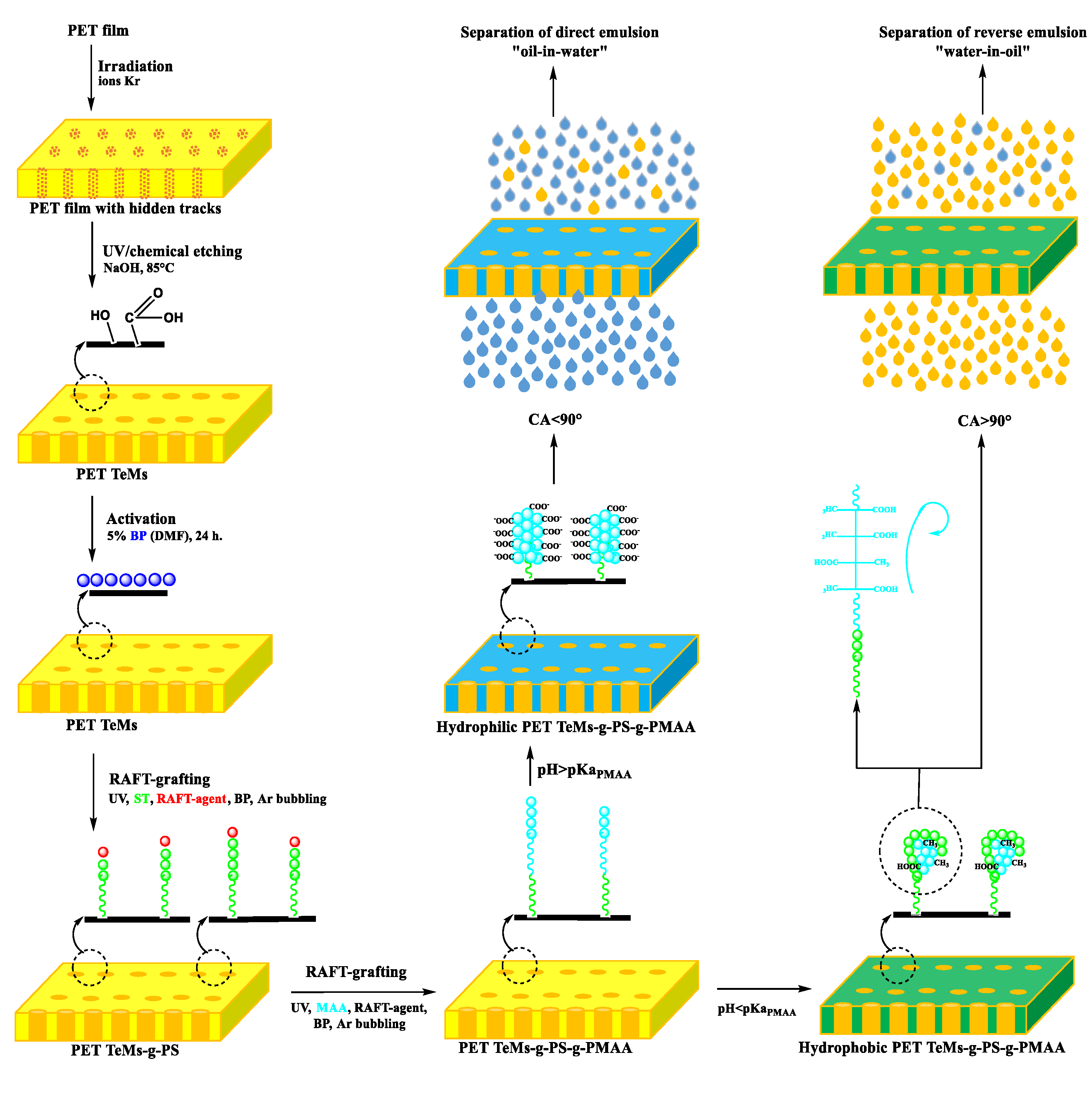

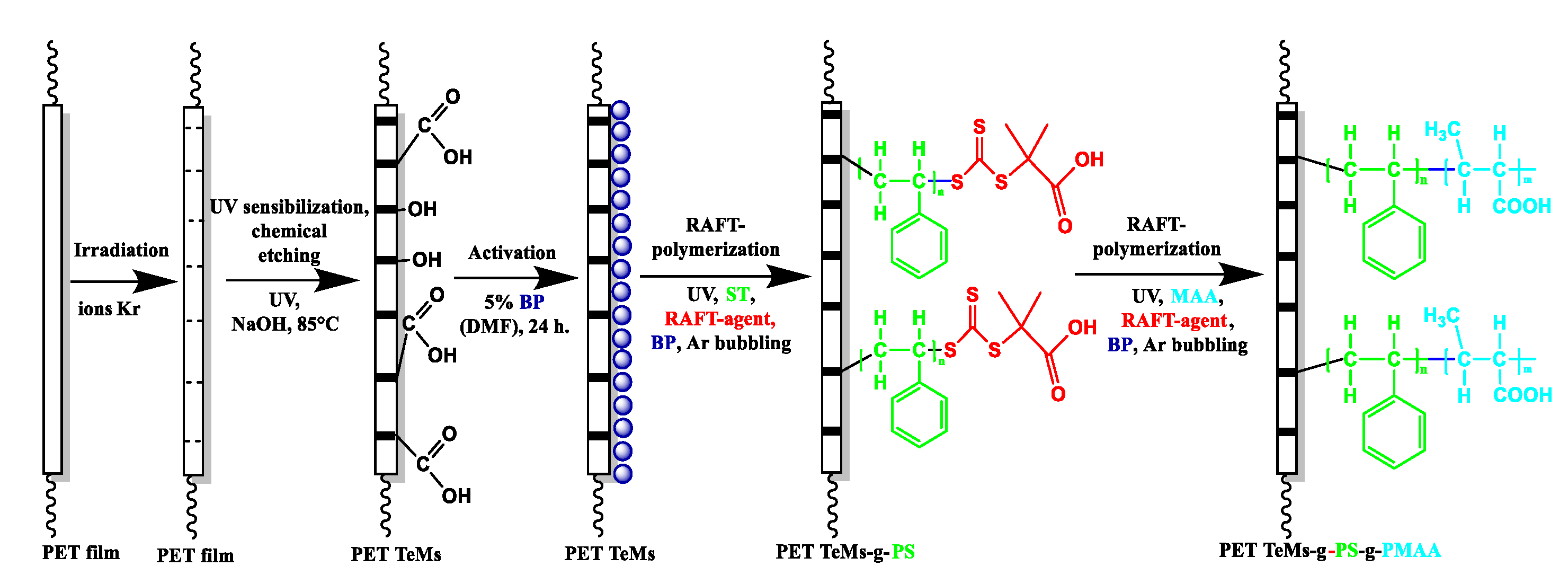

2.2. Preparation and Modification of Track-Etched Membranes

2.2.1. Track-Etched Membranes Base Preparation: Irradiation and Etching of PET Films

2.2.2. UV-Initiated RAFT Graft Polymerization for PET TeMs Modification

2.3. PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA characterization

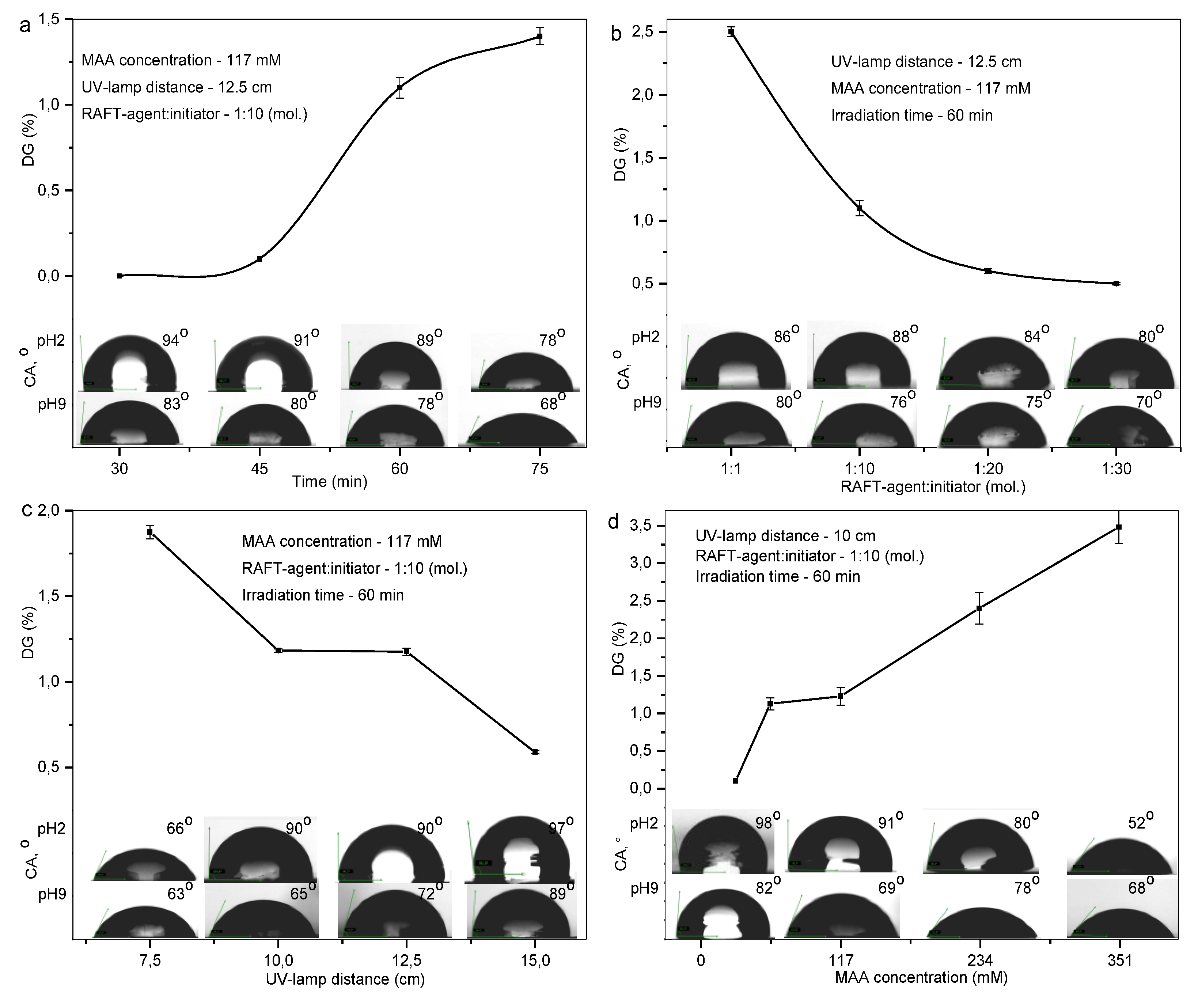

2.3.1. Contact Angle (CA) Measurement and pH-Responsivity Evaluation

2.3.2. Degree of Grafting (DG) Determination

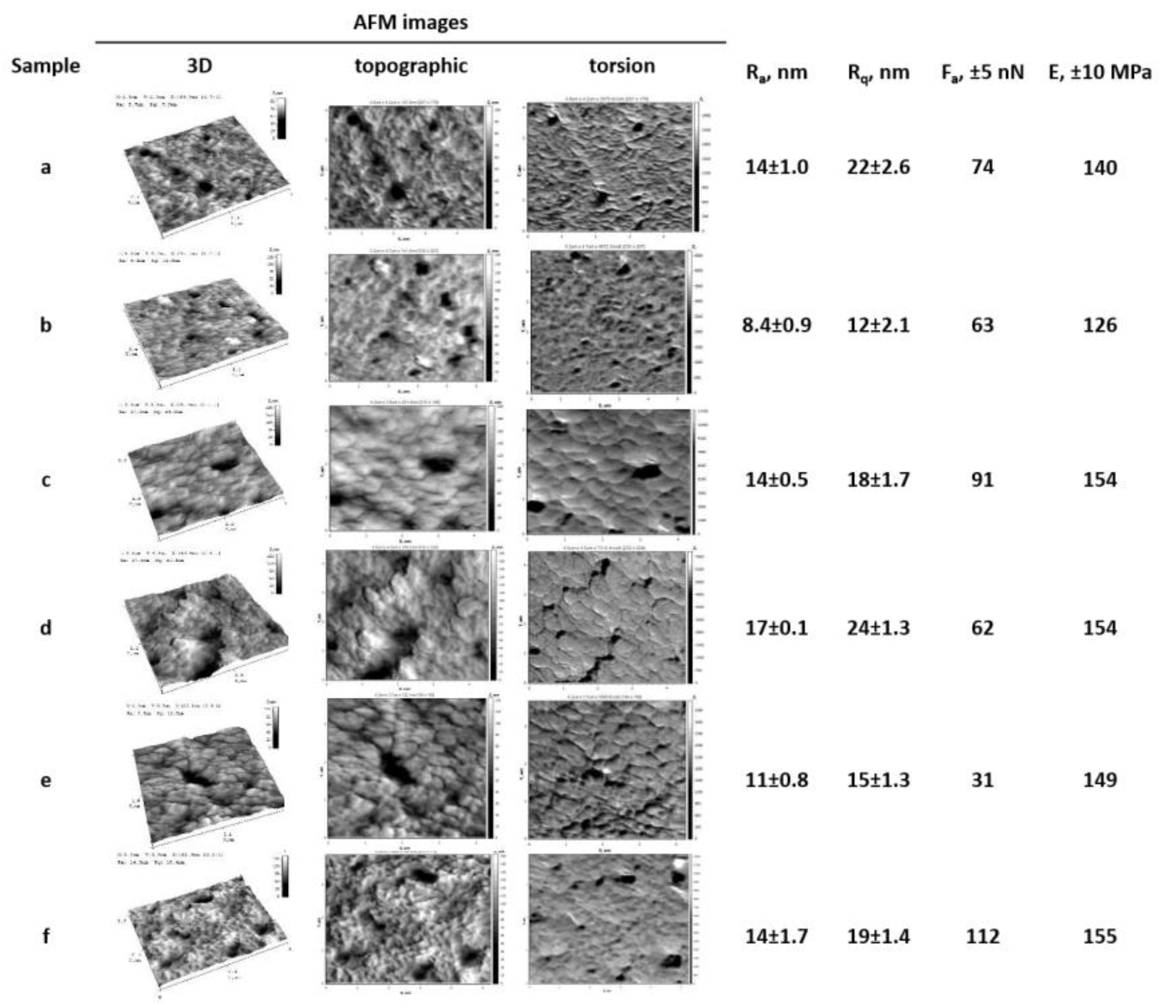

2.3.3. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.3.4. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

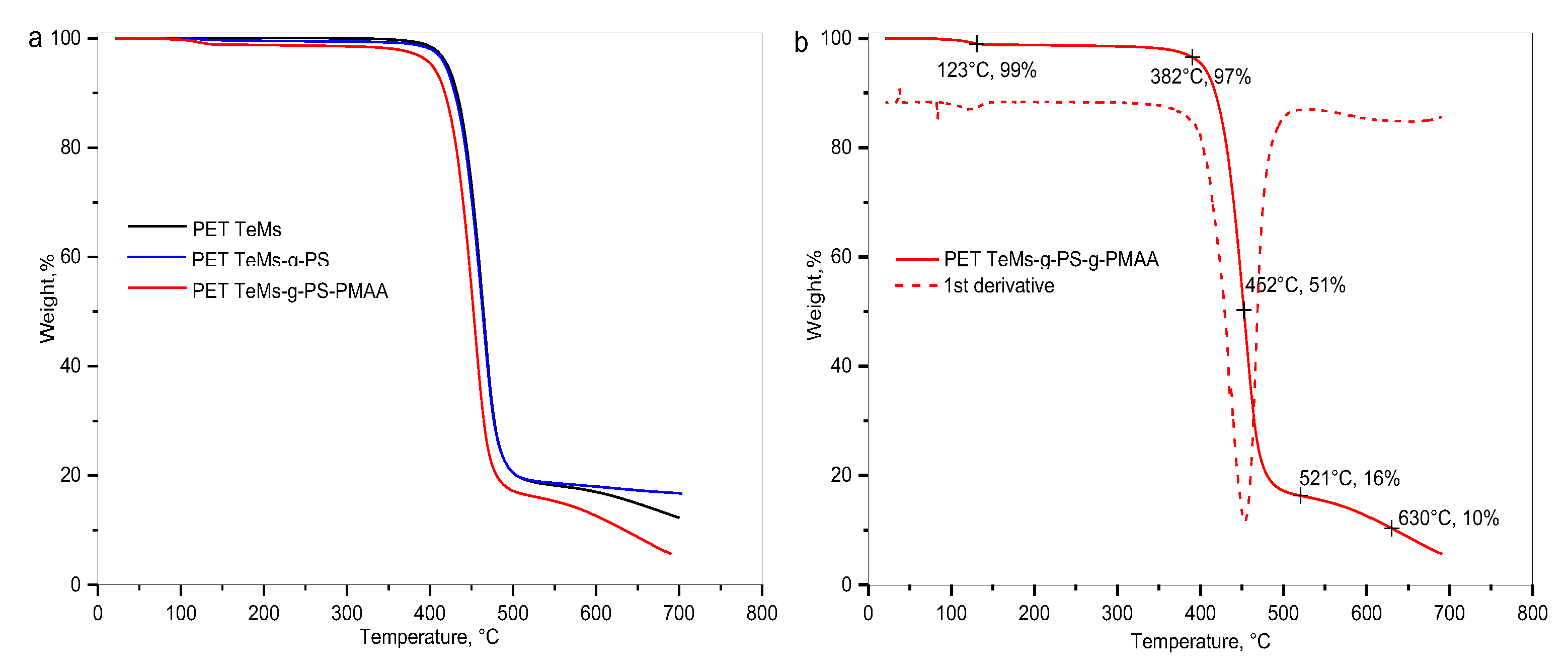

2.3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

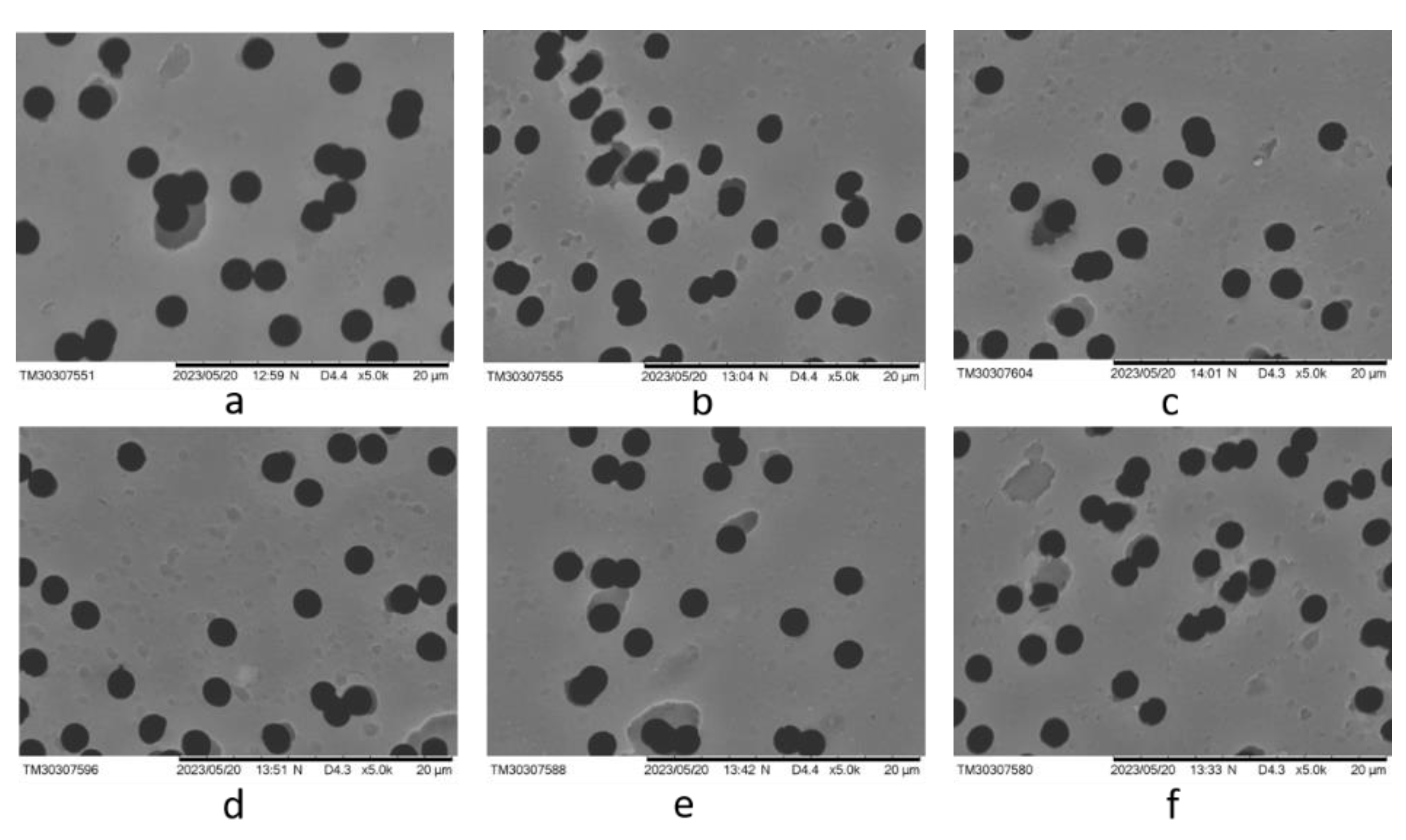

2.3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4. Performance Assessment of PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA in Water-Oil Emulsion Separation

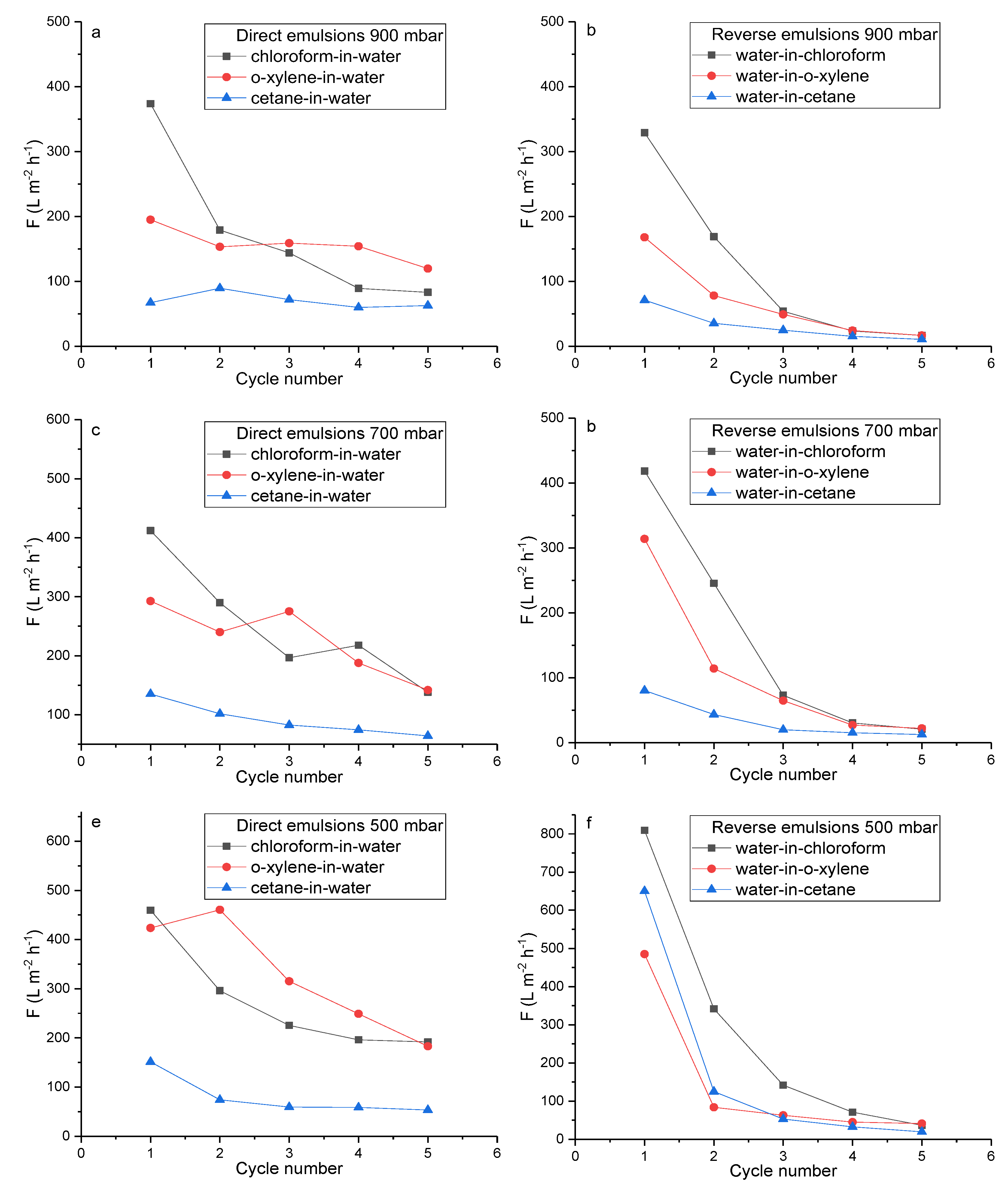

2.4.1. Evaluation of PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA Fouling and Flux Recovery in Water-Oil Separation

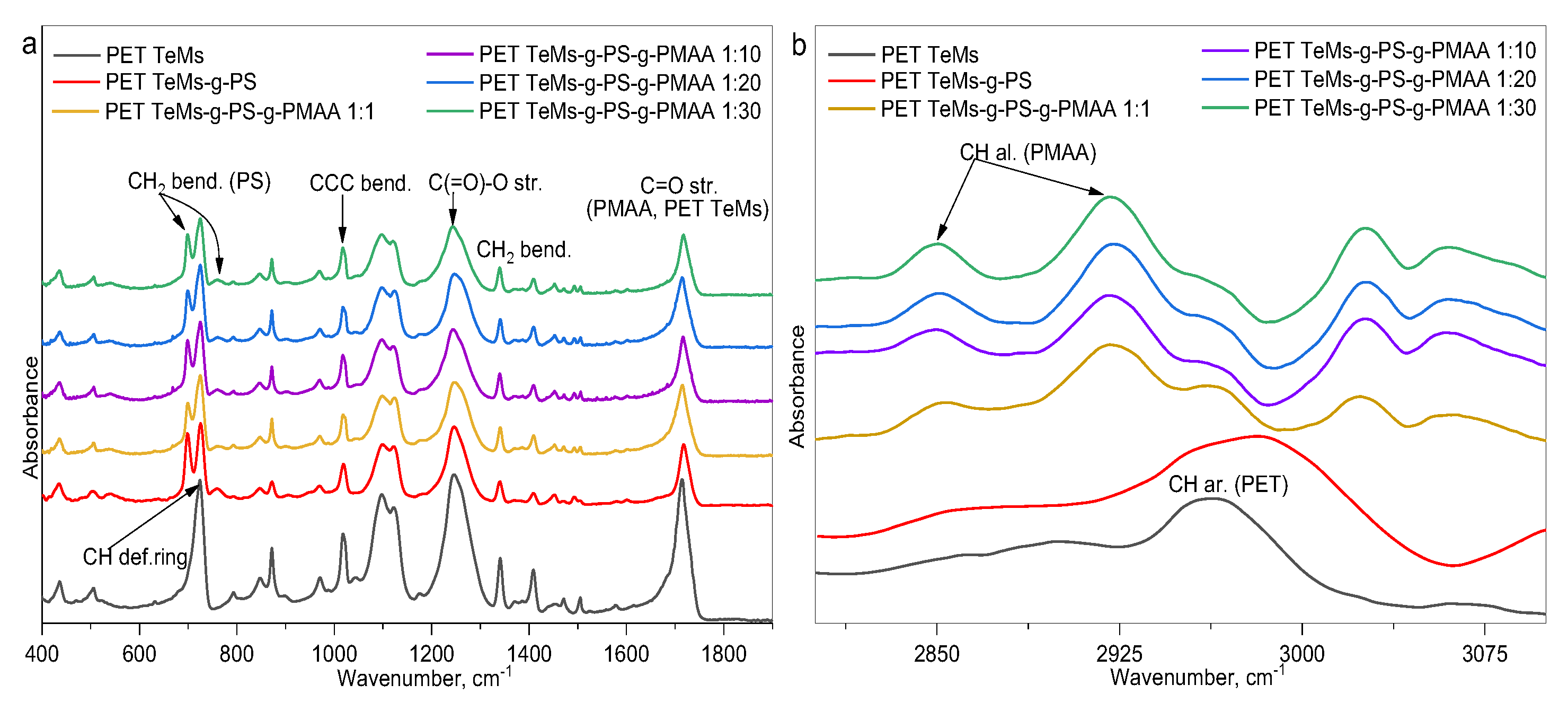

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.; Cui, P.; Jiang, W. A Review on Oil/Water Emulsion Separation Membrane Material. J Environ Chem Eng 2022, 10, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.; Cui, P.; Jiang, W. A Review on Oil/Water Emulsion Separation Membrane Material. J Environ Chem Eng 2022, 10, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Al Mohawes, K.B.; Khashab, N.M. Smart Membranes for Separation and Sensing. Chem Sci 2024, 15, 18772–18788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakar, K.K.; Cheriyan, B.V.; Anandakumar, R.; Murugathirumal, A.; Senthilkumar, A.; Nandhini, J.; Kataria, K.; Yabase, L. Stimuli-Responsive Smart Materials: Bridging the Gap between Biotechnology and Regenerative Medicine. Bioprinting 2025, 48, e00415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Sohail, M.; Baig, N.; Yuan, K.; Abdala, A.; Wahab, M.A. Next-Generation Stimuli-Responsive Smart Membranes: Developments in Oil/Water Separation. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 341, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Dong, Y.; Huang, C.; Hussain Abdalkarim, S.Y.; Yu, H.Y.; Tam, K.C. On-Demand plus and Minus Strategy to Design Conductive Nanocellulose: From Low-Dimensional Structural Materials to Multi-Dimensional Smart Sensors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 510, 161552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkov, I. V.; Mashentseva, A.A.; Güven, O.; Gorin, Y.G.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Zdorovets, M. V.; Zhidkov, I.S.; Cholach, S.O. Electron/Gamma Radiation-Induced Synthesis and Catalytic Activity of Gold Nanoparticles Supported on Track-Etched Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Membranes. Mater Chem Phys 2018, 217, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarvarti, S.K. Track-Etch Membranes Enabled Nano-/Microtechnology: A Review. Radiat Meas 2009, 44, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsbay, M.; Güven, O. Grafting in Confined Spaces: Functionalization of Nanochannels of Track-Etched Membranes. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2014, 105, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.K.; Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Sangaraju, S.; Ran, F. Functional Polymeric Membrane Materials: A Perspective from Versatile Methods and Modification to Potential Applications. Polymer Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Semsarilar, M.; Abetz, V.; Semsarilar, M.; Abetz, V. Polymerizations by RAFT: Developments of the Technique and Its Application in the Synthesis of Tailored (Co)Polymers. Macromol Chem Phys 2021, 222, 2000311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.H.; Caldona, E.B.; Advincula, R.C. PET-RAFT Polymerization under Flow Chemistry and Surface-initiated Reactions. Polym Int 2022, 72, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, A.W.; Klerer, J. Modification of Pet Surfaces with End-Functionalized Polymers Prepared from Raft Agents to Achieve Antibacterial Properties = Modifikasi Permukaan Pet Dengan Polimer-Polimer Fungsional Dari Agen Raft Untuk Mencapai Sifat Antibakteri. J Electrochem Soc 2015, 124, 192C–192C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Ren, R.; Li, H.; Cao, B. Preparation of Dual Stimuli-Responsive PET Track-Etched Membrane by Grafting Copolymer Using ATRP. Polym Adv Technol 2013, 24, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeszhanov, A.B.; Korolkov, I.V.; Shakayeva, A.K.; Lissovskaya, L.I.; Zdorovets, M.V. Preparation of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Track-Etched Membranes for the Separation of Water-Oil Emulsions. Eurasian Journal of Chemistry 2023, 2023, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, S.L.; Abidin, M.N.Z.; Ma’amor, A.; Hashim, N.A.; Hashim, M.L.H. Polyethylene Terephthalate Membrane: A Review of Fabrication Techniques, Separation Processes, and Modifications. Sep Purif Technol 2025, 354, 129343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashentseva, A.A.; Khassen, T.G.; Krasnov, V.A.; Zhumazhanova, A.T.; Kassymzhanov, M.T. МОДИФИКАЦИЯ ПОВЕРХНОСТИ ПЭТФ ТРЕКОВЫХ МЕМБРАН ФУНКЦИОНАЛЬНЫМИ МОНОМЕРАМИ ПОД ВОЗДЕЙСТВИЕМ УСКОРЕННЫХ ЭЛЕКТРОНОВ. Вестник НЯЦ РК 2020, 0, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmanbek, N.; Sütekin, S.D.; Barsbay, M.; Aimanova, N.A.; Mashentseva, A.A.; Alimkhanova, A.N.; Zhumabayev, A.M.; Yanevich, A.; Almanov, A.A.; Zdorovets, M. V. Environmentally Friendly Loading of Palladium Nanoparticles on Nanoporous PET Track-Etched Membranes Grafted by Poly(1-Vinyl-2-Pyrrolidone) via RAFT Polymerization for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 18700–18714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friebe, A.; Ulbricht, M. Controlled Pore Functionalization of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Track-Etched Membranes via Surface-Initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Langmuir 2007, 23, 10316–10322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinska, K.; Bryjak, M. Plasma Modified Track-Etched Membranes for Separation of Alkaline Ions. The Open Access Journal of Science and Technology AgiAl Publishing House 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakayeva, A.K.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Zhumazhanova, A.T.; Korolkov, I.V.; Zdorovets, M.V. Fabrication of Hydrophobic PET Track-Etched Membranes Using 2,2,3,3,4,4,4-Heptafluorobutyl Methacrylate for Water Desalination by Membrane Distillation. EURASIAN JOURNAL OF CHEMISTRY 2024, 29, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakayeva, A.K.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Borissenko, A.N.; Kassymzhanov, M.T.; Zhumazhanova, A.T.; Khlebnikov, N.A.; Nurkassimov, A.K.; Zdorovets, M. V.; Güven, O.; Korolkov, I. V. Surface Modification of Polyethylene Terephthalate Track-Etched Membranes by 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7-Dodecafluoroheptyl Acrylate for Application in Water Desalination by Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. Membranes (Basel) 2024, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkov, I. V.; Kuandykova, A.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Güven, O.; Gorin, Y.G.; Zdorovets, M. V. Modification of PET Ion-Track Membranes by Silica Nanoparticles for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation of Salt Solutions. Membranes 2020, Vol. 10, Page 322 2020, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, J.; Gui, X.; Hou, B.; Mo, D.; Lu, L.; Yao, H. Hydrophobic Modified PET Ion Track-Etched Membrane for Oil/Water Separation. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 54, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeszhanov, A.B.; Muslimova, I.B.; Melnikova, G.B.; Petrovskaya, A.S.; Seitbayev, A.S.; Chizhik, S.A.; Zhappar, N.K.; Korolkov, I. V.; Güven, O.; Zdorovets, M. V. Graft Polymerization of Stearyl Methacrylate on PET Track-Etched Membranes for Oil–Water Separation. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansawad, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Shang, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Qing, Y.; Zhao, S.; You, S.; Li, W. Smart Membranes for Oil/Water Emulsions Separation: A Review. Advanced Membranes 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Dunderdale, G.J.; England, M.W.; Hozumi, A. Oil/Water Separation Techniques: A Review of Recent Progresses and Future Directions. J Mater Chem A Mater 2017, 5, 16025–16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, S.; Rezaei, N.; Hamedi, H.; Zendehboudi, S.; Duan, X. Superhydrophobic and Superoleophilic Membranes for Oil-Water Separation Application: A Comprehensive Review. Mater Des 2021, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Mao, X.; Gao, Z.; Luo, S.; Kipper, M.J.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. Recent Advances in Electrospinning Smart Membranes for Oil/Water Separation. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 55, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimova, I.B.; Zhumanazar, N.; Melnikova, G.B.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Zhatkanbayeva, Z.K.; Chizhik, S.A.; Zdorovets, M. V.; Güven, O.; Korolkov, I. V. Preparation and Application of Stimuli-Responsive PET TeMs: RAFT Graft Block Copolymerisation of Styrene and Acrylic Acid for the Separation of Water–Oil Emulsions. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 14425–14437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.N.; Li, J.J.; Luo, Z.H. Toward Efficient Water/Oil Separation Material: Effect of Copolymer Composition on PH-Responsive Wettability and Separation Performance. AIChE Journal 2016, 62, 1758–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Loh, X.J.; Tan, B.H.; Li, Z. PH-Responsive Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Copolymer Decorated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Remotely Controlled Oil-in-Water Nanoemulsion Separation. Macromol Rapid Commun 2019, 40, 1800013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimova, I.B.; Zhatkanbayeva, Z.K.; Omertasov, D.D.; Melnikova, G.B.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Güven, O.; Chizhik, S.A.; Zdorovets, M. V.; Korolkov, I. V. Stimuli-Responsive Track-Etched Membranes for Separation of Water–Oil Emulsions. Membranes (Basel) 2023, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Cameron, A. Dual-Responsive Polymers Synthesized via RAFT Polymerization for Controlled Demulsification and Desorption. Journal of Polymer Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, Q.; Wang, M.; Liu, D.; Dong, L.; Cui, Z.; He, B.; Li, J.; Yan, F. Superhydrophilic/Underwater Superoleophobic PVDF Ultrafiltration Membrane with PH-Responsive Self-Cleaning Performance for Efficient Oil-Water Separation. Sep Purif Technol 2024, 330, 125420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Deng, X.; An, Z. PH-Induced Inversion of Water-in-Oil Emulsions to Oil-in-Water High Internal Phase Emulsions (HIPEs) Using Core Cross-Linked Star (CCS) Polymer as Interfacial Stabilizer. Macromol Rapid Commun 2014, 35, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeszhanov, A.B.; Korolkov, I. V; Dosmagambetova, S.S.; Zdorovets, M. V; Güven, O. Recent Progress in the Membrane Distillation and Impact of Track-Etched Membranes. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkov, I. V.; Narmukhamedova, A.R.; Melnikova, G.B.; Muslimova, I.B.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Zhatkanbayeva, Z.K.; Chizhik, S.A.; Zdorovets, M. V. Preparation of Hydrophobic PET Track-Etched Membranes for Separation of Oil–Water Emulsion. Membranes (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, M.; Wahidur Rahaman, S.M.; Améduri, B.; Poli, R.; Ladmiral, V. RAFT Synthesis of Well-Defined PVDF-b-PVAc Block Copolymers. Polym Chem 2016, 7, 6918–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, D.J. A Guide to the Synthesis of Block Copolymers Using Reversible-Addition Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) Polymerization. Chem Soc Rev 2014, 43, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.J. Modeling the Molecular Weight Distribution of Block Copolymer Formation in a Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain Transfer Mediated Living Radical Polymerization. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 2005, 43, 5643–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Sun, D.; Song, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W. Preparation of Multifunctional PET Membrane and Its Application in High-Efficiency Filtration and Separation in Complex Environment. J Hazard Mater 2024, 474, 134669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Su, Y.; Ning, X.; Chen, W.; Peng, J.; Jiang, Z. Graft Polymerization of Methacrylic Acid onto Polyethersulfone for Potential PH-Responsive Membrane Materials. J Memb Sci 2010, 347, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Fierro, D.A.; Camacho-Cruz, L.A.; Bustamante-Torres, M.R.; Hidalgo-Bonilla, S.P.; Bucio, E. Modification of Cotton Gauzes with Poly(Acrylic Acid) and Poly(Methacrylic Acid) Using Gamma Radiation for Drug Loading Studies. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, R.C. Der Einfluss Der UV-Initiierten RAFT-Polymerisation Auf Die Strukturen Und Eigenschaften von Polymernetzwerken. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tan, J. Utilization of Poor RAFT Control in Heterogeneous RAFT Polymerization. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 4669–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hou, Q.; Liu, H.; Ye, X. One-Pot, Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Poly(Styrene-N,N′-Methylenebis(2-Propenamide)-Acrylic Acid) and Poly(Styrene-N,N′-Methylenebis(2-Propenamide)-Methacrylic Acid) Microspheres for Adsorptive Removal of Heavy Metal Ions. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2024, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkov, I. V.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Zdorovets, M. V.; Gorin, Y.G.; Güven, O.; Dosmagambetova, S.S.; Khlebnikov, N.A.; Serkov, K. V.; Krasnopyorova, M. V.; Milts, O.S.; et al. Modification of PET Ion Track Membranes for Membrane Distillation of Low-Level Liquid Radioactive Wastes and Salt Solutions. Sep Purif Technol 2019, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarpour, M.; Hosseinpour, S.; Haddad Irani-nezhad, M.; Orooji, Y.; Khataee, A. Fabrication of Ti2SnC-MAX Phase Blended PES Membranes with Improved Hydrophilicity and Antifouling Properties for Oil/Water Separation. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Gao, Y.; Yin, W.; Gao, B.; Yue, Q. Multi-Functional Membrane with Double-Barrier and Self-Cleaning Ability for Emulsion Separation: Fouling Model and Long-Term Operation. J Memb Sci 2024, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.C.; Ouyang, L.; Yuan, S. Switchable Superlyophobic PAN@Co-MOF Membrane for on-Demand Emulsion Separation and Efficient Soluble Dye Degradation. Sep Purif Technol 2024, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lin, J.; An, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L. Enhancing Hydrophilicity and Comprehensive Antifouling Properties of Microfiltration Membrane by Novel Hyperbranched Poly(N-Acryoyl Morpholine) Coating for Oil-in-Water Emulsion Separation. React Funct Polym 2020, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | I2850/I1409 | I2850/I1245 | I2925/I1409 | I2925/I1245 | I1712/I1409 | I1712/I1245 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET TeMs | - | - | - | - | 4.91 | 0.93 |

| PET TeMs-g-PS | - | - | - | - | 1.67 | 0.31 |

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA RAFT agent:initiator 1:1, DGPMAA=2.5% | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.00 | 0.91 |

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA RAFT agent:initiator 1:10, DGPMAA=1.1% | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 5.40 | 0.84 |

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA RAFT agent:initiator 1:20, DGPMAA=0.6% | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 4.83 | 0.88 |

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA RAFT agent:initiator 1:30, DGPMAA=0.5% | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.12 | 4.00 | 0.82 |

| Material | Property | Emulsion | Pressure | F, L m-2 h-1 | R, % | FR, % | TR, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PMAA | Hydrophilicity pH>pKaPMAA | Chloroform-in-water | 900 mbar | 370 | 90 | 88 | 2 | This work |

| 700 mbar | 410 | 92 | - | - | ||||

| 500 mbar | 460 | 93 | - | - | ||||

| o-Xylene-in-water | 900 mbar | 195 | 98 | 69 | 52 | |||

| 700 mbar | 290 | 98 | - | |||||

| 500 mbar | 420 | 99 | - | |||||

| Cetane-in-water | 900 mbar | 70 | 93 | 54 | 64 | |||

| 700 mbar | 135 | 90 | - | |||||

| 500 mbar | 150 | 95 | - | |||||

| Hydrophobicity pH<pKaPMAA | Water-in-chloroform | 900 mbar | 330 | 85 | 91 | 25 | ||

| 700 mbar | 420 | 92 | - | |||||

| 500 mbar | 810 | 96 | - | |||||

| Water-in-o-xylene | 900 mbar | 170 | 92 | 81 | 19 | |||

| 700 mbar | 310 | 92 | ||||||

| 500 mbar | 485 | 88 | ||||||

| Water-in- cetane |

900 mbar | 70 | 99 | 70 | 10 | |||

| 700 mbar | 80 | 94 | ||||||

| 500 mbar | 650 | 93 | ||||||

| PET TeMs-g-PS-g-PAA | Hydrophilicity pH>pKaPAA | Chloroform-in-water | 900 mbar | 2500 | 94±5 | 82 | 22 | [30] |

| Hydrophobicity pH<pKaPAA | Water-in-chloroform | 900 mbar | 1400 | 97±1 | 96 | 46 | ||

| Ti2SnC-MAX-PES | Hydrophilicity | Oil-in-water | 0.3 kPa | 355 | 80 | 65 | - | [49] |

| MIL88A@TA@APTES-PVDF | Superhydrophilicity | Oil-in-water | Gravity | 2600 | 99 | 94 | - | [50] |

| PAN@Co-MOF | Superoleophobicity, water wetting | Cyclohexane-in-water | 2-8 kPa | 1600 | 99 | - | - | [51] |

| Superhydrophobi-city, oil wetting | Water-in- cyclohexane |

2-8 kPa | 1040 | 99 | - | - | ||

| M-PD/HPA@PVDF | Hydrophilicity | Hexane-in-water | 0.3 kPa | 150 | 99 | 83 | 37 | [52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).