Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data Screening

3.2. Self-Compassion as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Thin-Ideal Internalisation and WBI and Eating Pathology

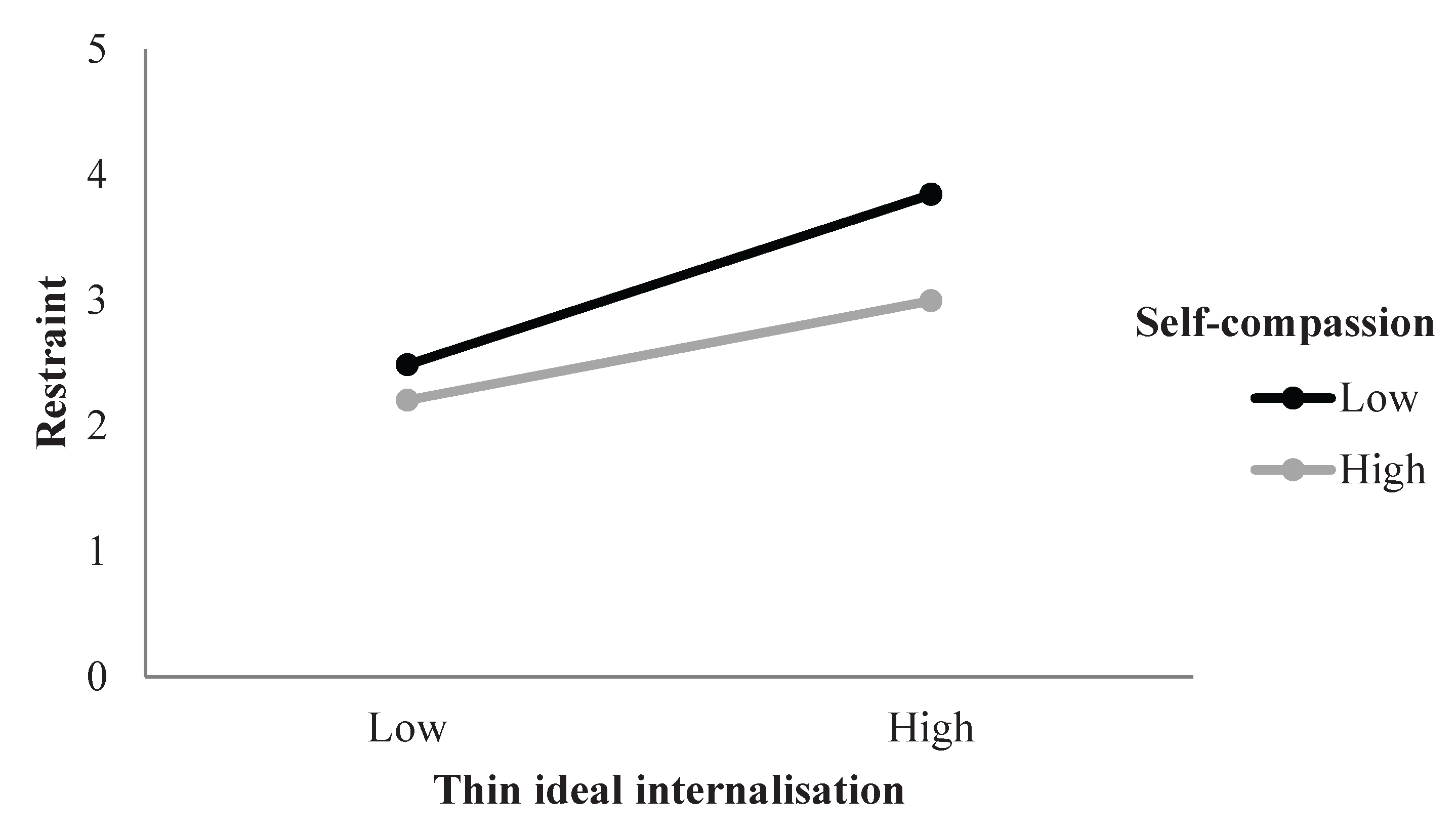

3.2.1. Restraint

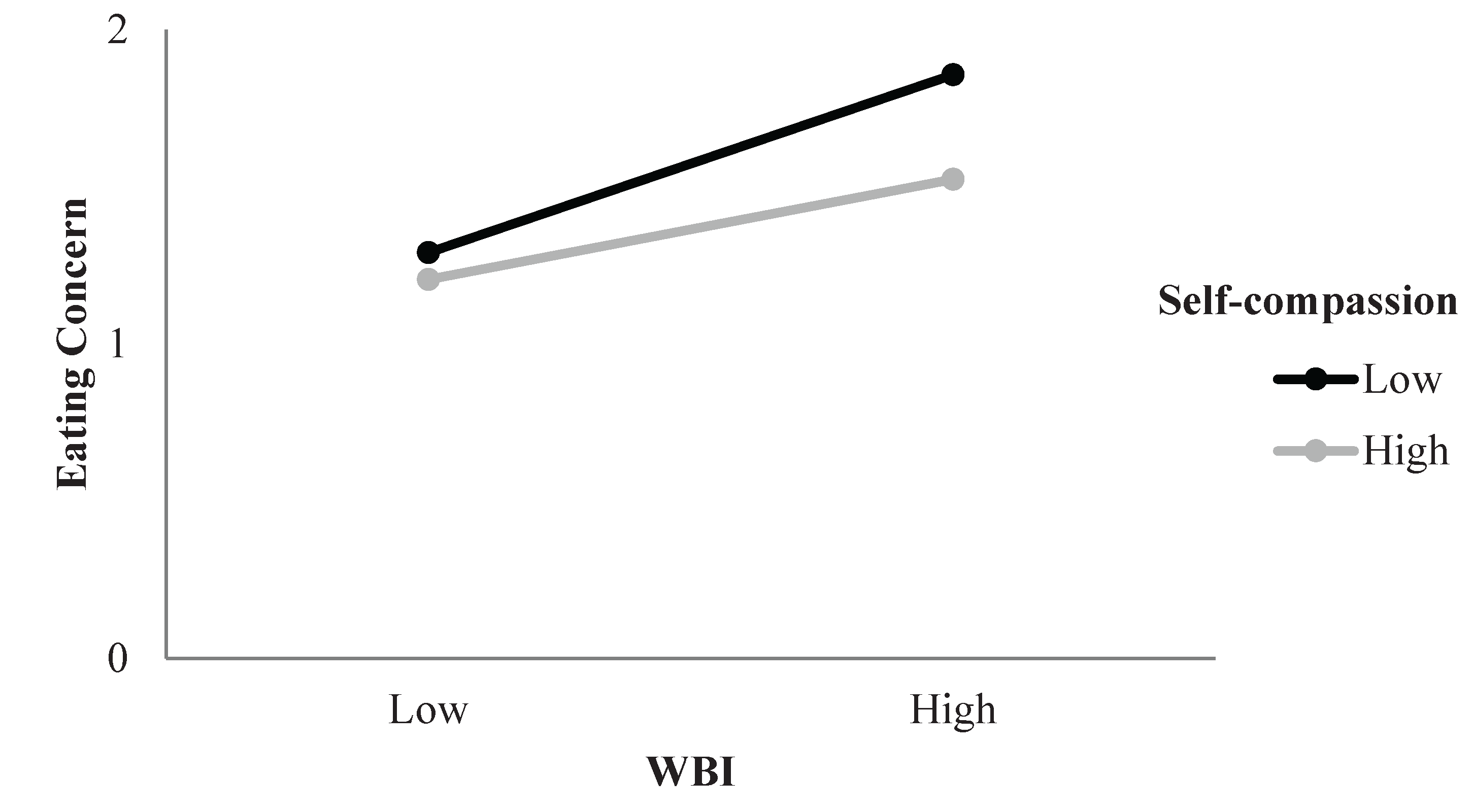

3.2.2. Eating Concern

3.2.3. Shape Concern

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI WBI |

Body mass index Weight bias internalisation |

References

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M. P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2019, 109((5)), 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Access Economics, Deloitte. Paying the price, second edition: The economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia; 2024; Available online: https://butterfly.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Paying-the-Price_Second-Edition_2024_FINAL.pdf.

- Romano, K. A.; Heron, K. E.; Henson, J. M. Examining associations among weight stigma, weight bias I ternalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms: Does weight status matter? Body Image 2021, 37, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvey, N. A.; White, M. A. The internalization of weight bias is associated with severe eating pathology among lean individuals. Eating Behaviors 2015, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J. K.; Stice, E. Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2001, 10((5)), 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. K.; Heinberg, L. J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, F. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance, 1st ed.; American Psychological Association, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall, C. S. Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1994, 66((5)), 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R. M.; Heuer, C. A. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity 2009, 17((5)), 941–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, B.; de la Piedad Garcia, X.; Kite, J.; Hill, B.; Cooper, K.; Flint, S. Weight stigma in Australia: a public health call to action. Public Health Research & Practice 32(3) 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. M.; Lessard, L. M.; Pearl, R. L.; Himmelstein, M. S.; Foster, G. D. International comparisons of weight stigma: Addressing a void in the field. International Journal of Obesity 2021, 45((9)), 1976–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R. L.; Puhl, R. M. Weight bias internalization and health: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews 2018, 19((8)), 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E. Review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa and an exploration of the mechanisms of action. Clinical Psychology Review 1994, 14((7)), 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, S.; Ward, L. M.; Hyde, J. S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin 2008, 134((3)), 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbert, K. M.; Racine, S. E.; Klump, K. L. Research review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders-a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2015, 56((11)), 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E. Interactive and mediational etiologic models of eating disorder onset: Evidence from prospective studies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2016, 12((1)), 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C. N.; Shaw, H.; Rohde, P. Meta-analytic review of dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Intervention, participant, and facilitator features that predict larger effects. Clinical Psychology Review 2019, 70, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Mazotti, L.; Weibel, D.; Agras, W. S. Dissonance prevention program decreases thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms: A preliminary experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2000, 27((2)), 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Shaw, H.; Burton, E.; Wade, E. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2006, 74((2)), 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, E.; Jenkinson, E.; Falconer, L.; Griffiths, C. How effective are psychosocial interventions at improving body image and reducing disordered eating in adult men? A systematic review. Body Image 2023, 47, 101612–101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E. R. Understanding the relative contributions of internalised weight stigma and thin ideal internalisation on body dissatisfaction across body mass index. Master's thesis, Ohio University, 2023. OhioLINK. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=ohiou168259303369045&disposition=inline. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, J. A.; Kinkel-Ram, S.; Myers, B.; Hunger, J. M. A systematic review of weight stigma and disordered eating cognitions and behaviors. Body Image 2024, 48, 101678–101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutter, S.; Russell-Mayhew, S.; Saunders, J. F. Towards a sociocultural model of weight stigma. Eating and Weight Disorders 2021, 26((3)), 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Mooney, T. A.; Lozano, L. L.; Adams, E. A.; Makriyianis, H. M.; Liss, M. Psychological inflexibility moderates the relationship between thin-ideal internalization and disordered eating. Eating Behaviors 2020, 36, 101345–101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T. D.; Park, C. L.; Gorin, A. Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: A review of the literature. Body Image 2016, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A. C.; Vimalakanthan, K.; Carter, J. C. Understanding the roles of self-esteem, self-compassion, and fear of self-compassion in eating disorder pathology: An examination of female students and eating disorder patients. Eating Behaviors 2014, 15((3)), 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasylkiw, L.; MacKinnon, A. L.; MacLellan, A. M. Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image 2012, 9((2)), 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity 2003, 2((2)), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. Self-Compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology 2023, 74((1)), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeth, A.; Gumley, A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review 2012, 32((6)), 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. D.; Rude, S. S.; Kirkpatrick, K. L. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality 2007, 41((4)), 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J. Positive body image, intuitive eating, and self-compassion protect against the onset of the core symptoms of eating disorders: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 54((11)), 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, J. B.; Forman, M. J. Evaluating the indirect effect of self-compassion on binge eating severity through cognitive–affective self-regulatory pathways. Eating Behaviors 2013, 14((2)), 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, E. M.; Herndier, R. E.; Sander, A. C. Self-compassion, internalized weight stigma, psychological well-being, and eating behaviors in women. Mindfulness 2021, 12((5)), 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, K. C.; McComb, S. E.; Mills, J. S. Testing a self-compassion micro-intervention before appearance-based social media use: Implications for body image. Body Image 2022, 40, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T. L.; Russell, H. L.; Neal, A. A. Self-compassion as a moderator of thinness-related pressures' associations with thin-ideal internalization and disordered eating. Eating Behaviors 2015, 17, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, F.; Waller, G. Is self-compassion relevant to the pathology and treatment of eating and body image concerns? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2020, 79, 101856–101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C. M. Reduction of internalized weight bias via mindful self-compassion: Theoretical framework and results from a randomized controlled trial. Doctoral thesis, Duke University, 2022. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. A healthy lifestyle-WHO recommendations. WHO. 6 May 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations.

- Rø; Reas, D. L.; Stedal, K. Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in Norwegian adults: Discrimination between female controls and eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review 2015, 23((5)), 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, L. M.; Harriger, J. A.; Heinberg, L. J.; Soderberg, T.; Kevin Thompson, J. Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4-revised (SATAQ-4R). International Journal of Eating Disorders 2017, 50((2)), 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R. L.; Puhl, R. M. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image 2014, 11((1)), 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso, L. E.; Latner, J. D. Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity 2008, 16((S2)), S80–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D.; Tóth-Király, I.; Knox, M. C.; Kuchar, A.; Davidson, O. The development and validation of the state self-compassion scale (long-and short form). Mindfulness 2021, 12((1)), 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C. G.; Belgin, S. Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders; Guilford Press, 2008; pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, K. A.; Heron, K. E.; Sandoval, C. M.; Howard, L. M.; MacIntyre, R. I.; Mason, T. B. A meta-analysis of associations between weight bias internalization and conceptually-related correlates: A step towards improving construct validity. Clinical Psychology Review 2022, 92, 102127–102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. F.; Nutter, S.; Russell-Mayhew, S. Examining the conceptual and measurement overlap of body dissatisfaction and internalized weight stigma in predominantly female samples: A meta-analysis and measurement refinement study. Frontiers in Global Women's Health 2022, 3, 877554–877554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd edition ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, K. S.; Latner, J. D.; Puhl, R. M.; Vartanian, L. R.; Giles, C.; Griva, K.; Carter, A. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite 2016, 102, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J.; Samson, L.; Maiolino, N.; et al. Self-compassion and its barriers: predicting outcomes from inpatient and residential eating disorders treatment. Journal of Eating Disorders 2022, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 31.48 | 10.62 | - | |||||||

| 2 | BMI | 26.66 | 7.14 | .24 | - | ||||||

| 3 | Self-compassion | 3.11 | 0.71 | .21 | -.09 | 0.92 | |||||

| 4 | WBIS | 3.95 | 1.51 | -.13 | .41 | -.54 | 0.94 | ||||

| 5 | Thin-ideal Internalisation | 3.22 | 0.92 | -.28 | -.05 | -.35 | .54 | 0.82 | |||

| 6 | Restraint | 2.92 | 1.67 | 0.01 | .09 | -.28 | .43 | .43 | 0.84 | ||

| 7 | Eating Concern | 1.50 | 0.44 | -.21 | .13 | -.50 | .67 | .53 | .60 | 0.83 | |

| 8 | Shape Concern | 4.04 | 1.71 | -.10* | .30 | -.52 | .81 | .57 | .59 | .78 | 0.91 |

| Step | Variable | R2 | Adjusted R2 | R2 Change | B | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BMI | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| 2 | BMI | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.000 | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| Self-compassion | -0.12 | -0.05 | 0.00 | ||||

| Thin-ideal Internalisation | 0.50*** | 0.28*** | 0.05*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.28*** | 0.25*** | 0.03*** | ||||

| 3 | BMI | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Self-compassion | -0.14 | -0.06 | 0.00 | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalization | 0.50*** | 0.28*** | 0.05*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.27*** | 0.24*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation x Self-compassion | -0.27* | -0.11* | 0.01* | ||||

| WBI x Self-compassion | 0.040 | 0.028 | 0.001 |

| Step | Variables | R2 | Adjusted R2 | R2 Change | B | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BMI | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.01*** | 0.19*** | 0.03*** |

| Age | -0.01*** | -0.25*** | 0.06*** | ||||

| 2 | BMI | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.44 | -0.005 | -0.08 | 0.00 |

| Age | -0.00 | -0.04 | 0.00 | ||||

| Self-compassion | -0.10*** | -0.16*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation | 0.09*** | 0.19*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.15*** | 0.51*** | 0.11*** | ||||

| 3 | BMI | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.01 | -0.01 | -0.08 | 0.00 |

| Age | -0.00 | -0.03 | 0.00 | ||||

| Self-compassion | -0.11*** | -0.18*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation | 0.09*** | 0.18*** | 0.02*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.15*** | 0.50*** | 0.10*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation x Self-compassion | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| WBI x Self-compassion | -0.04** | -0.11** | 0.01** |

| Step | Variables | R2 | Adjusted R2 | R2 Change | B | Β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08*** | 0.34*** | 0.11*** |

| Age | -0.03*** | -0.18*** | 0.03*** | ||||

| 2 | BMI | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Age | 0.01* | 0.06* | 0.00* | ||||

| Self-compassion | -0.27*** | -0.11*** | 0.01*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation | 0.41*** | 0.22*** | 0.03*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.70*** | 0.62*** | 0.16*** | ||||

| 3 | BMI | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Age | 0.01* | 0.06* | 0.00* | ||||

| Self-compassion | -0.27*** | -0.11*** | 0.01*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation | 0.41*** | 0.22*** | 0.03*** | ||||

| WBI | 0.70*** | 0.62*** | 0.16*** | ||||

| Thin-ideal internalisation x Self-compassion | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||||

| WBI x Self-compassion | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).