Introduction

Deep sea is a highly dynamic and active environment able to influence global biogeochemical and ecological processes (Acinas et al., 2021). Modulated by seafloor geometry and bottom-intensified turbulence, sedimentary processes and boundary exchange on the deep seafloor drive trace-metal cycling (Du et al., 2025). Still, long-term phosphate availability is governed by the interplay between seafloor and continental weathering, directly impacting marine productivity and oxygenation across geological timescales (Sharoni and Halevy, 2023) Large-scale current systems and ecological mechanisms shape the modular structure of oceanic microbial communities, emphasizing the roles of dispersal limitation and environmental selection (Milke et al., 2023). Collectively, these studies portray the deep sea as a structurally and functionally complex domain mediating physical and biological oceanic processes.

Alongside these geochemical and microbial insights, the study of collective behavior in biological systems has advanced significantly, particularly in terrestrial and near-surface marine environments. Swarming in birds, fish and insects has been extensively analyzed under well-characterized sensory and environmental conditions (Gal and Kronauer, 2022; Papadopoulou et al., 2022; Sarfati and Peleg, 2022; Cavagna et al., 2022; Maity and Morin, 2023; Sayin et al., 2025; Khona et al., 2025). In contrast, the collective dynamics of deep-sea organisms remain poorly understood, constrained by observational challenges such as extreme pressure, low temperatures and the absence of light. Existing models of collective movement often rely on visual or gradient-based interactions that are ill-suited to the abyssal zone. Moreover, limited in situ data from depths beyond 1,000 meters have restricted the development of biophysically realistic frameworks for deep-sea behavior. While some studies have addressed microbial spatial organization or bioluminescent signaling (Román et al. ,2019; Burford and Robison, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2024), few have accounted for the combined effects of pressure, low-Reynolds number hydrodynamics and sensory attenuation (Kunze 2011). A recent in situ kinematic analysis of bony fishes across a 0–6,000 m depth gradient showed significantly slower swimming speeds under high pressure, indicating direct impacts of hydrostatic pressure on locomotor performance (Woodworth et al., 2025). Further, a study on deep-sea shrimp Opsloporoidea demonstrated depth-related adaptations in photophores and opsin proteins, reflecting reduced environmental light and signaling attenuation (DeLeo and Bracken-Grissom, 2025).

This leaves a substantial gap in our understanding of how physical constraints govern coordination and structure in deep marine systems such that controlled simulation-based approaches are required to model and test plausible behavioral strategies under extreme oceanic conditions.

To address this, we propose a set of numerical simulations designed to model the movement and interaction strategies of active agents in lightless, high-pressure environments. Our simulations incorporate depth-related variables like hydrostatic pressure, signal attenuation, swarm alignment, turbulence and predator-induced dynamics and their influence on behavioral metrics including cohesion, alignment, dispersion and responsiveness. By isolating these effects in silico, we aim to generate reproducible and interpretable outcomes that may provide insight into deep-sea biological behavior in the absence of empirical data.

We will proceed as follows: the next section details our modeling framework and simulation procedures; we then present individual and comparative results across environmental conditions; finally, we discuss implications, limitations and potential extensions of our findings.

Materials and Methods

We detail here the computational framework and mathematical formulations to simulate and analyze the collective behavior of active agents under surface and deep-sea conditions. By integrating agent-based modeling, fluid dynamics and biologically inspired rules, we aim to establish a reproducible methodology to investigate how environmental constraints influence swarm dynamics, coordination and structural organization.

Environmental context and behavioral feature framework for deep-sea simulation. We simulated deep-sea conditions corresponding to depths between 3,000 and 6,000 meters, a range representative of the bathyal and abyssal zones. At these depths, organisms are exposed to hydrostatic pressures of approximately 300 to 600 atmospheres (atm), with ambient temperatures ranging from 0 to 4°C (Tamburini et al.; Valdes et al., 2021). Sunlight is entirely absent and locomotion occurs in a regime dominated by viscous fluid dynamics due to low Reynolds numbers, especially for small-bodied organisms (Brewer et al., 2022). Nutrient availability is scarce and spatially heterogeneous and bioluminescence represents one of the few available modes of visual signaling (Martini and Haddock, 2017). Our simulated environment incorporated these constraints, including pressure-tolerant mechanical models, low-temperature motility parameters and sensory limitations relevant to chemosensation, mechanoreception and bioluminescent cue detection.

The analysis of collective behavior in our simulations was structured around eleven quantitative features, grouped into structural, dynamic, and signaling-related categories.

- 1)

Structural features characterize the spatial and organizational properties of the swarm. Cohesion, defined as the average pairwise distance between agents, is expected to decrease under surface conditions due to environmental constraints that limit close-range interactions (Pedrami and Gordon, 2008.). Cluster count, representing the number of discrete subgroups within a swarm, is anticipated to be higher in deep-sea conditions, reflecting fragmentation caused by impaired sensory perception. Local density variance, which measures spatial inhomogeneity across the domain, is also expected to increase at depth, indicating the emergence of isolated clusters or voids due to reduced alignment efficiency (Pedrami and Gordon 2008; Lomidze et al., 2017)..

- 2)

Dynamic features capture the temporal evolution of movement patterns and their stability. Reaction time, measuring the latency between external stimuli (e.g., predator presence) and the agent’s response, is predicted to be slower in deep-sea environments, reflecting reduced sensory acuity and muscular response. Trajectory curvature, describing the nonlinearity of motion paths, is expected to increase under deep conditions due to disoriented or avoidance-driven movement. Acceleration fluctuation, tracking changes in speed and direction over time, is anticipated to be greater at depth, where unstable coordination may lead to more abrupt movement changes. Velocity variance quantifies inter-agent variability in speed and is likewise expected to rise in the deep sea, where heterogeneous local interactions reduce collective regulation. Turning frequency, defined as the number of directional changes per unit time, is hypothesized to increase in unstructured or disrupted swarms, especially under low-visibility conditions.

- 3)

Signaling and coordination features relate to the agents’ ability to transmit and interpret spatial information. Alignment, measured as the magnitude of the mean heading vector across agents, is expected to be lower in deep sea, where sensory input do not support stronger directional consensus. Swarm polarity, a related metric based on angular agreement with the group’s average heading, is similarly anticipated to decline with depth due to reduced communication and feedback. Orientation entropy, calculated from the distribution of agent headings, is expected to increase in deep-sea conditions, reflecting more disordered, non-aligned behavior. Communication success rate, defined as the proportion of emitted signals successfully perceived within a given range, is predicted to drop significantly in high-pressure, lightless environments where bioluminescent cues attenuate quickly and sensory radii shrink.

Overall, these eleven features together provide a comprehensive framework for quantifying the effects of environmental depth on both the structure and function of collective biological systems, forming the basis for comparative analysis in our simulation experiments.

Computational framework and agent-based simulation design. All simulations were conducted using a custom-built Python environment employing NumPy for numerical operations, Matplotlib for visualization and SciPy for statistical analysis. Simulation scripts were executed in a Jupyter environment running on Python 3.10. Each experiment was designed as an agent-based simulation (ABS) with deterministic and stochastic components. Agents were modeled as self-propelled particles in a bounded, two-dimensional domain , where units. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed to eliminate edge effects. For each simulation, agents were initialized at random positions with unit-norm velocity vectors, , drawn uniformly from the unit circle. Agent dynamics were governed by a hybrid update rule that combined alignment, repulsion, environmental perturbations and biologically motivated behaviors such as predator avoidance and stimulus tracking. A fixed time-step Euler integration scheme was used, with unit and each simulation was iterated over time steps.

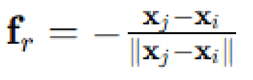

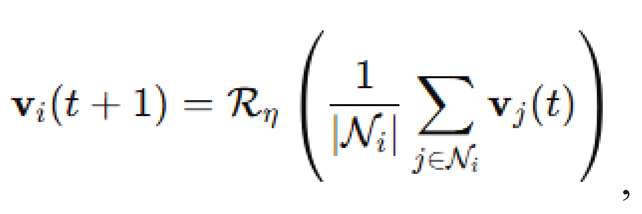

Agent motion and alignment dynamics. Each agent was characterized by a position vector and a velocity vector , updated according to a Vicsek-inspired alignment mechanism with additive noise (Clusella and Pastor-Satorras, 2021). Specifically, velocity updates followed the rule

where

is the set of neighbors within alignment radius

and

is a rotation operator that adds uniformly distributed angular noise

to the resulting average vector. The velocity vector was normalized after each update to maintain constant speed,

, where

. Position updates were computed by the standard Euler step:

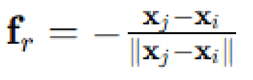

To ensure spatial coherence in dense configurations, repulsion was included using a radial force model with a threshold radius

. If

. A normalized repulsive force

was added to the velocity update, scaled by a constant

. These rules jointly dictated the local interactions that govern emergent group alignment, cohesion and trajectory smoothing. With this mechanism, each agent could both align with neighbors and avoid crowding, providing a baseline for comparison under additional environmental influences.

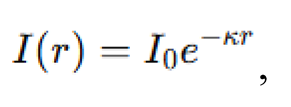

Deep-sea pressure and communication attenuation modeling. In modeling pressure-dependent effects for deep-sea conditions, we parameterized hydrostatic pressure

as a function of depth

using the standard oceanographic relation:

where

,

and

. Simulated depths were set at

, corresponding to

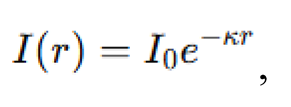

. Signal attenuation for bioluminescent communication was modeled by an exponential decay function:

where is the initial signal intensity and is the attenuation coefficient, set as a function of pressure , with baseline and scaling . This model reduced the effective communication radius of agents by defining a minimum signal threshold , such that . We expect that, as pressure increases, decreases, leading to smaller effective neighborhoods and diminished swarm coherence.

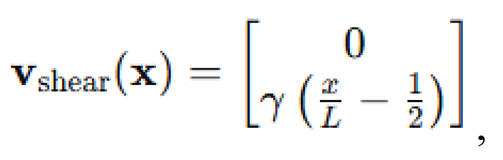

Shear flow perturbations. To evaluate the effects of fluid dynamics on collective motion, we introduced externally imposed flow fields into the swarm environment. The velocity of each agent was perturbed by a shear-induced vector field defined by:

where

is the shear gradient coefficient, varied as

for shallow, mid-depth and deep conditions respectively. This created a laminar shear flow along the

-axis with gradient in the

-direction, mimicking current stratification effects. The final velocity update became:

Velocity normalization was applied afterward to maintain

unit speed. The effect of this field was to distort local alignment structures,

inducing elongation and dispersion along the direction of flow. Additionally,

random turbulent noise was modeled using a Gaussian perturbation

, added to the velocity

before normalization, with

to simulate background turbulence (Balan et al., 2025). By combining shear and stochastic forces, this method provided a scalable approach to investigating how hydrodynamic disturbances affect swarm integrity at various depths.

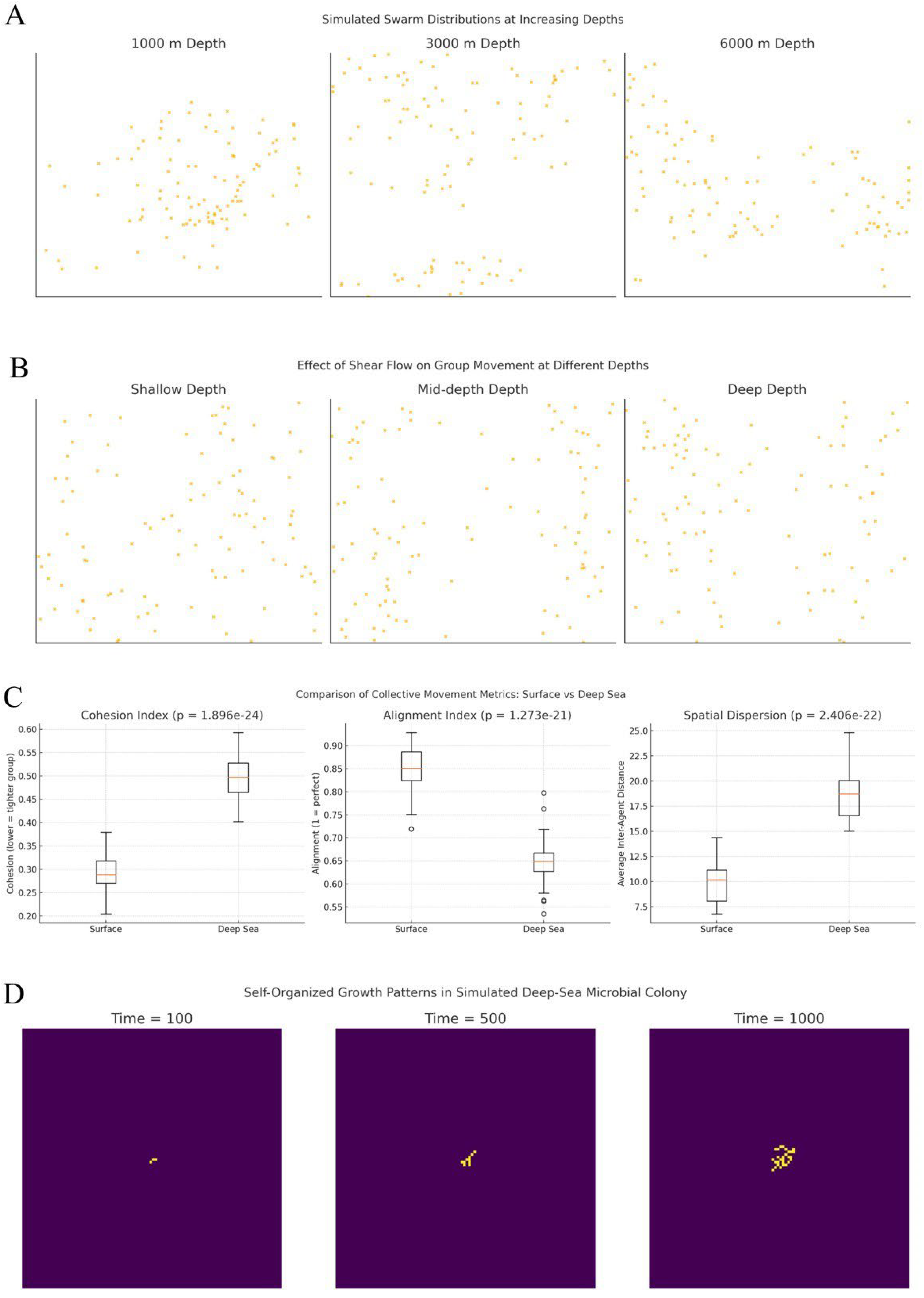

Microbial colony growth via diffusion-limited aggregation. To model the spatial development of microbial colonies in the absence of advection, we used a two-dimensional lattice-based diffusion-limited aggregation (DLA) framework (Ren et al., 2006). A binary lattice

was initialized with a seed at the center

and random walkers were introduced at lattice boundaries. Each walker followed a discrete random walk governed by:

with uniform probabilities excluding the stationary case

. A walker adhered to the cluster if any Moore neighbor was occupied. The process was iterated for

10

4 walkers or until a predefined colony size was reached. This stochastic growth model naturally produced dendritic, fractal-like patterns analogous to microbial mats. The morphology of the aggregate was characterized by computing the fractal dimension

via box-counting and radial density profiles

were fitted using power laws of the form

. The DLA procedure served as a generative model of colony structure without imposing explicit shape rules, allowing the quantification of self-organization in lightless, nutrient-limited environments analogous to deep-sea environments.

Predator-avoidance in lightless environments. Predator-avoidance was modeled using a distance-based repulsion mechanism. A predator agent was introduced with a fixed position and velocity . At each time step, swarm agents computed a repulsion vector:

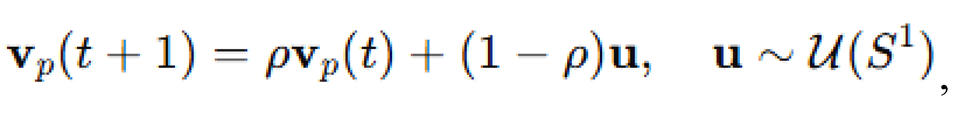

scaled by a coefficient . This vector was added to the alignment update prior to normalization. The predator moved with velocity updated according to a persistent random walk:

with memory coefficient

. This created realistic pursuit behavior without

directional targeting. The mean distance between agents and the predator was

tracked over time, along with the cluster cohesion index

, to evaluate escape efficiency and group fragmentation. This simulation explored

how non-visual strategies like local repulsion could enable swarm survival in

visually inaccessible environments.

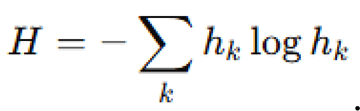

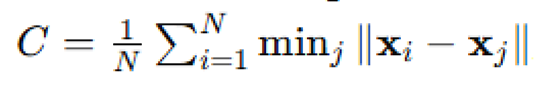

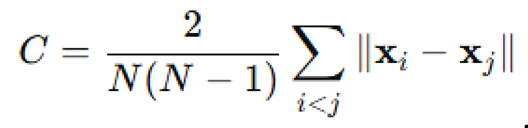

Quantitative metrics and statistical analysis. To compare swarm behavior across simulations, several scalar metrics were computed. Cohesion was defined as the average pairwise distance:

Alignment was computed as the magnitude of the mean velocity vector:

Dispersion was measured by the standard deviation of agent positions along each axis and swarm polarity was computed as the dot product between agent headings and the group mean direction.

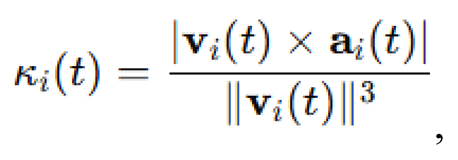

To quantify the curvature of an agent’s trajectory, curvature for agent at time was defined as:

where:

is the velocity vector,

is the acceleration vector,

denotes the 2D scalar cross product .

In discrete simulation terms:

The mean trajectory curvature across all agents and time steps was:

Orientation entropy was calculated using a discretized angular histogram of directions , through:

Comparisons between surface and deep-sea conditions were performed using independent two-sample -tests. For each metric, we verified normality assumptions using the Shapiro-Wilk test and checked for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. Statistical significance was reported at the level. All visualizations, including box plots and swarm snapshots, were generated using Matplotlib.

Results

We present here the results of simulations designed to evaluate how surface and deep-sea conditions influence a range of behavioral and structural swarm metrics. Our analysis focuses on quantifying differences in cohesion, alignment, spatial dispersion, response dynamics and group coordination, offering a detailed characterization of how physical constraints shape collective motion in contrasting marine environments.

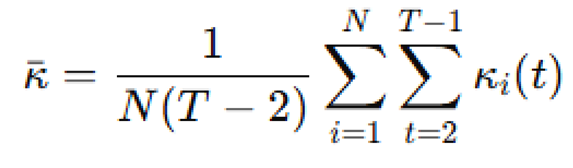

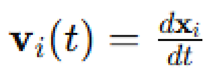

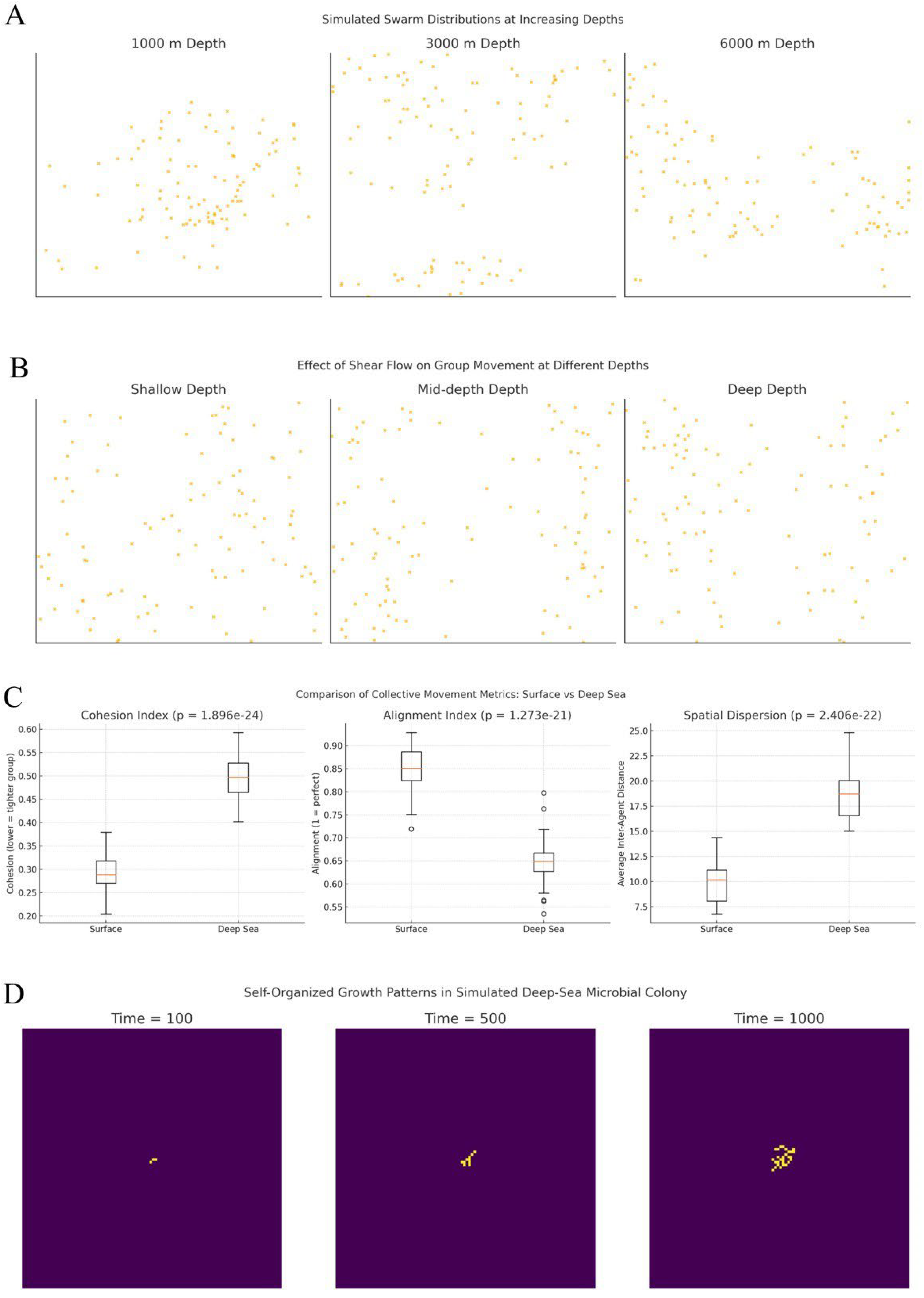

Structural features. Quantitative comparison of swarm structure between surface and deep-sea conditions revealed statistically significant differences across all evaluated parameters (p < 0.001 in all cases) (Figure 1). Average cohesion index increased from 0.29 at the surface to 0.49 in deep-sea conditions, indicating reduced spatial compactness. Similarly, dispersion values rose from 9.81 to 18.70, reflecting a wider spread of agent positions under environmental constraints such as low visibility and signal attenuation. Mean alignment index dropped from 0.85 to 0.65, showing decreased directional consensus in deep environments. Average pairwise distances rose from 7.86 to 14.54 and polarity decreased from 0.89 to 0.60, confirming that coordinated group motion is substantially impaired under simulated high-pressure conditions. Communication success, measured as the percentage of effectively received signaling events, declined from 83.99% at the surface to 39.87% in the deep sea, aligning with modeled bioluminescence attenuation and reduced interaction radii. Taken together, these outcomes suggest that swarms formed under high-pressure and low-light conditions exhibit systematically lower coherence, alignment and proximity.

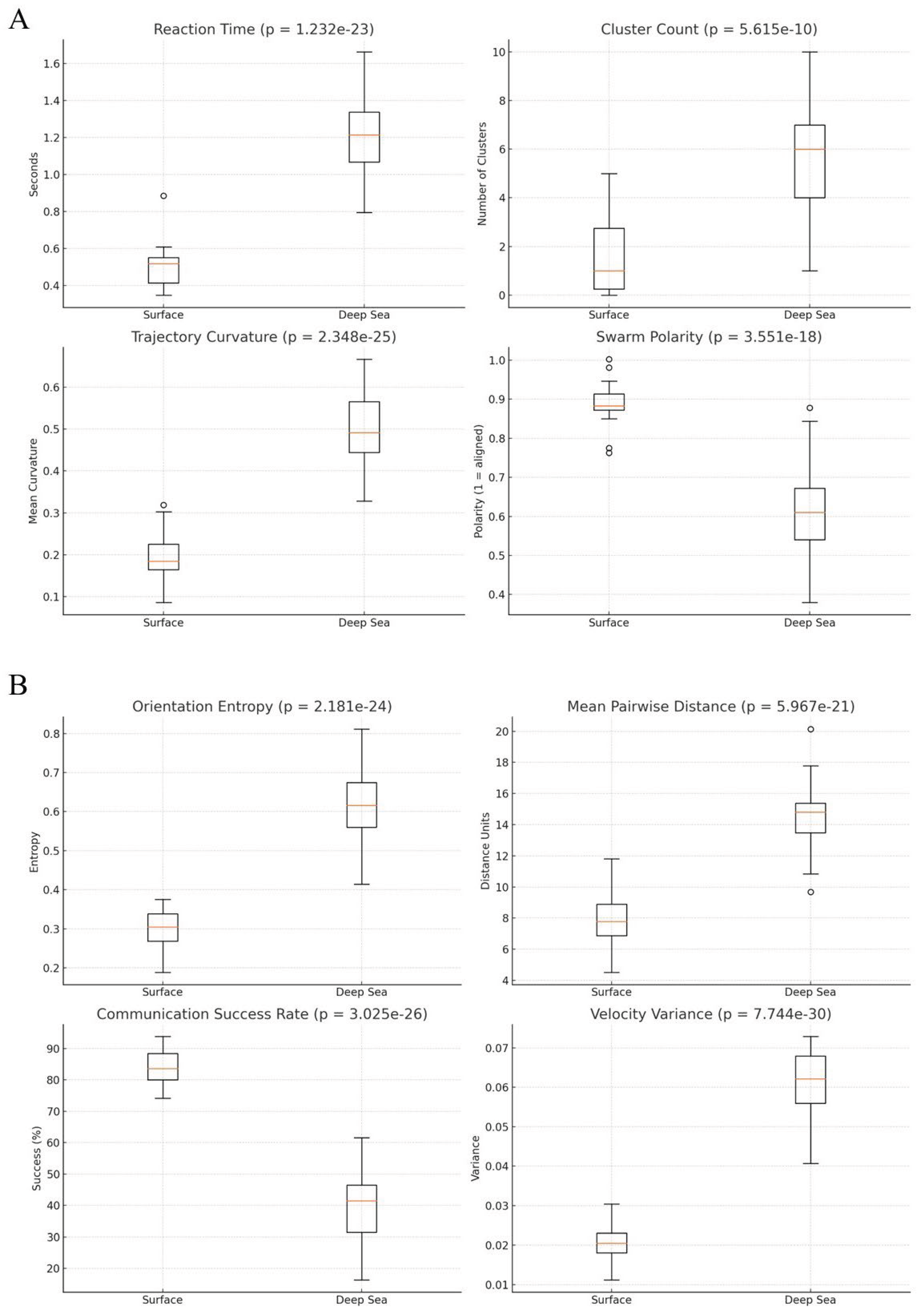

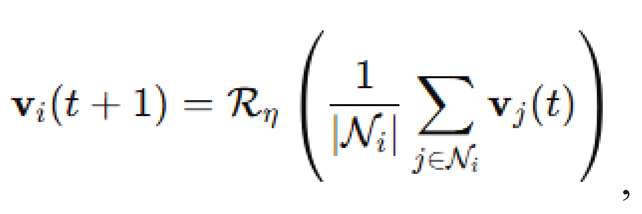

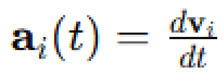

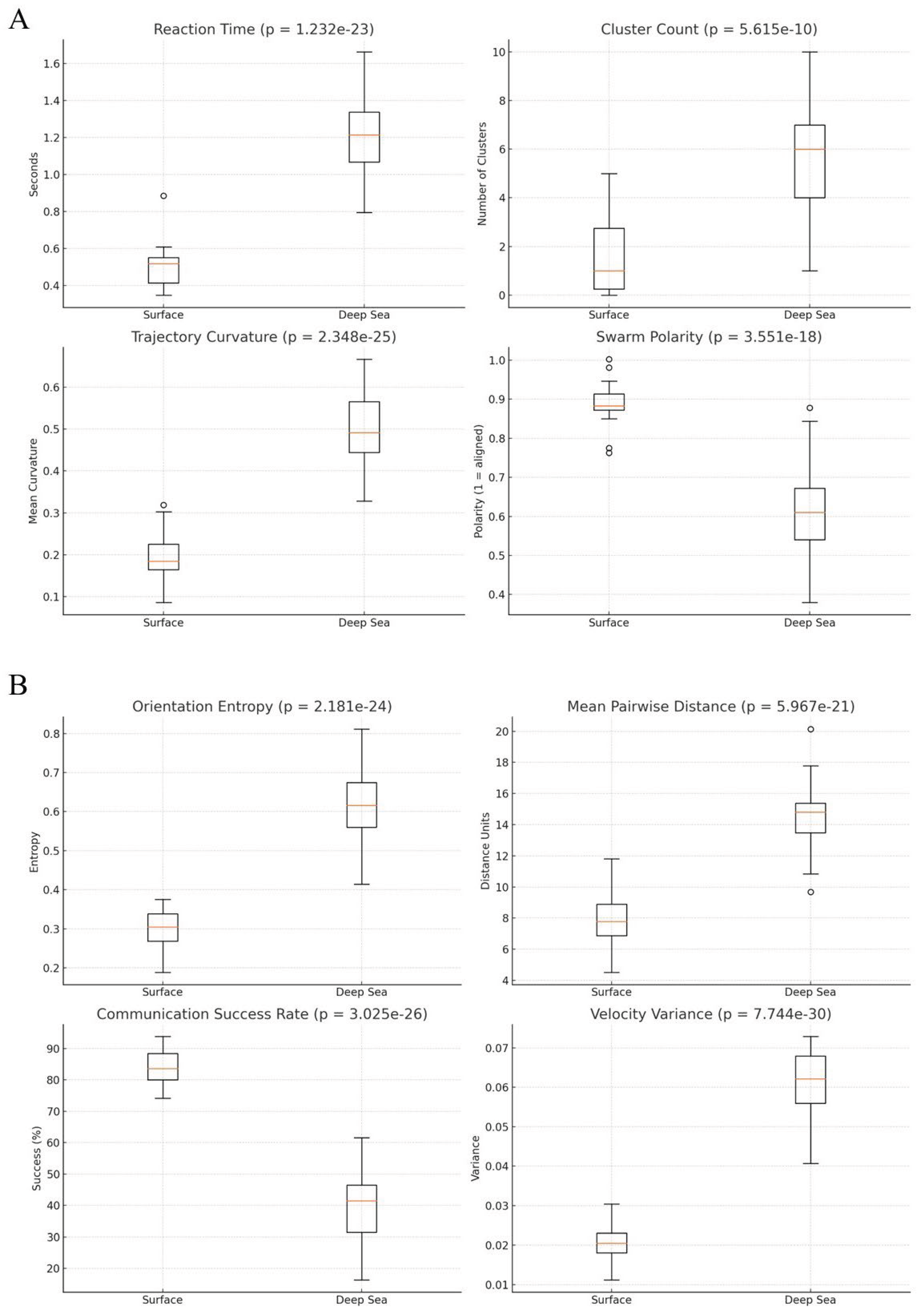

Dynamic, signaling and coordination features. Dynamic behavioral properties further confirmed substantial shifts under deep-sea conditions (p < 0.001 in all cases) (Figure 2). Reaction time increased significantly from 0.51 seconds at the surface to 1.21 seconds in deep water, indicating slower responsiveness to perturbation. Mean cluster count rose from 1.63 to 5.60, suggesting swarm fragmentation into disconnected subgroups in the absence of reliable global cues. Trajectory curvature, reflecting local path complexity, was elevated in the deep sea with an average of 0.50 compared to 0.19 at the surface, demonstrating that motion paths became more erratic and locally variable. Orientation entropy, measuring disorder in heading directions, doubled from 0.30 to 0.61 and velocity variance increased from 0.02 to 0.06, supporting the conclusion that both temporal and directional consistency degraded with increasing pressure and sensory limitations. The joint behavior of these metrics connects agent-level movement fluctuations with emergent swarm instability, reinforcing the interpretation that physical constraints on communication and motion may strongly affect not only the swarm’s configuration, but also its internal temporal stability.

Overall, our swarm simulations show statistically robust differences between surface and deep-sea conditions. Collective behavior under high-pressure and low-visibility regimes leads to lower cohesion, decreased alignment, greater dispersion, slower response and higher variability.

Figure 1.

Simulated behavioral responses of biological agents under deep-sea constraints. (A) Swarm distributions of bioluminescent agents at 1,000 m, 3,000 m and 6,000 m depth illustrate the impact of hydrostatic pressure on group cohesion. At 1,000 m, agents form tight clusters due to effective visual communication. At 3,000 m, signal attenuation reduces alignment, causing partial dispersion. At 6,000 m, swarms fragment and exhibit increased inter-agent spacing, reflecting diminished coordination under extreme pressure. (B) Swarm patterns under fluid shear simulating shallow, mid-depth and deep-sea conditions. Low shear preserves cohesive and uniform movement. Mid-level shear introduces elongation and partial dispersion. At high shear levels, typical of deeper regions, swarm structure becomes stretched and striated, showing how velocity gradients disrupt coordinated motion. (C) Box plots comparing collective movement metrics between surface and deep-sea environments. Surface swarms exhibit lower cohesion indices, higher alignment and reduced dispersion compared to deep-sea values (p < 0.001 in all cases), indicating significantly tighter and more coordinated group structures. (D) Microbial colony self-organization simulated through diffusion-limited aggregation. At time 100, growth is localized; by time 500, irregular radial branches emerge; and at time 1000, the colony forms a dendritic, fractal-like structure.

Figure 1.

Simulated behavioral responses of biological agents under deep-sea constraints. (A) Swarm distributions of bioluminescent agents at 1,000 m, 3,000 m and 6,000 m depth illustrate the impact of hydrostatic pressure on group cohesion. At 1,000 m, agents form tight clusters due to effective visual communication. At 3,000 m, signal attenuation reduces alignment, causing partial dispersion. At 6,000 m, swarms fragment and exhibit increased inter-agent spacing, reflecting diminished coordination under extreme pressure. (B) Swarm patterns under fluid shear simulating shallow, mid-depth and deep-sea conditions. Low shear preserves cohesive and uniform movement. Mid-level shear introduces elongation and partial dispersion. At high shear levels, typical of deeper regions, swarm structure becomes stretched and striated, showing how velocity gradients disrupt coordinated motion. (C) Box plots comparing collective movement metrics between surface and deep-sea environments. Surface swarms exhibit lower cohesion indices, higher alignment and reduced dispersion compared to deep-sea values (p < 0.001 in all cases), indicating significantly tighter and more coordinated group structures. (D) Microbial colony self-organization simulated through diffusion-limited aggregation. At time 100, growth is localized; by time 500, irregular radial branches emerge; and at time 1000, the colony forms a dendritic, fractal-like structure.

Figure 2.

Quantitative comparison of different features in surface versus deep-sea swarm conditions. The statistical values were p<0.001 in all cases. A) Box plots showing advanced collective behavior metrics in surface and deep-sea environments. Reaction time is slower at depth, indicating delayed responsiveness. Cluster count increases significantl0, suggesting group fragmentation. Trajectory curvature is higher in deep conditions, reflecting more erratic paths. Swarm polarity is reduced (p < 0.001), indicating diminished alignment and directional coherence. (B) Box plots of four extended features demonstrate deeper effects of environmental constraints. Orientation entropy rises markedly in the deep sea, indicating increased heading disorder. Mean pairwise distance grows significantly, confirming reduced cohesion. Communication success drops, reflecting severe sensory limitations. Velocity variance is greater at depth, suggesting instability in coordinated movement. Together, these metrics provide a robust and multidimensional characterization of the behavioral divergence induced by deep-sea physical constraints.

Figure 2.

Quantitative comparison of different features in surface versus deep-sea swarm conditions. The statistical values were p<0.001 in all cases. A) Box plots showing advanced collective behavior metrics in surface and deep-sea environments. Reaction time is slower at depth, indicating delayed responsiveness. Cluster count increases significantl0, suggesting group fragmentation. Trajectory curvature is higher in deep conditions, reflecting more erratic paths. Swarm polarity is reduced (p < 0.001), indicating diminished alignment and directional coherence. (B) Box plots of four extended features demonstrate deeper effects of environmental constraints. Orientation entropy rises markedly in the deep sea, indicating increased heading disorder. Mean pairwise distance grows significantly, confirming reduced cohesion. Communication success drops, reflecting severe sensory limitations. Velocity variance is greater at depth, suggesting instability in coordinated movement. Together, these metrics provide a robust and multidimensional characterization of the behavioral divergence induced by deep-sea physical constraints.

Conclusions

Our simulations showed that collective movement in active agents may be highly sensitive to environmental parameters such as pressure, turbulence and communication constraints. Under surface-level conditions, agents exhibited strong cohesion, high alignment, low dispersion and rapid response times, consistent with effective group coordination. In contrast, simulations under deep-sea conditions, modeled with high hydrostatic pressure, attenuated communication and reduced sensory range, led to degradation in swarm structure and dynamics. Specifically, group cohesion decreased, dispersion increased and directional alignment weakened, supported by statistically significant changes in average pairwise distance, polarity and entropy. Moreover, deep-sea agents exhibited more variable and curved trajectories, indicating reduced navigational efficiency and increased behavioral noise. Predator-avoidance behavior resulted in higher fragmentation and slower mean escape responses at depth, with swarms displaying an increased number of clusters. Microbial colony simulations under passive diffusion conditions reproduced branching and dendritic growth patterns, reinforcing the idea that self-organization can persist even in the absence of directed motion or rich sensory input. Collectively, our simulations confirmed that changes in the biophysical environment substantially affect both the internal structure and external functionality of coordinated biological systems.

The novelty of our approach lies in its synthetic design tailored specifically to mimic extreme underwater conditions in the absence of empirical data. We modeled biological constraints through pressure-sensitive communication decay, turbulent flow interference and restricted sensory access. This abstraction allowed us to systematically test a range of behavioral hypotheses, while isolating individual variables for analysis. Compared to existing models of swarming behavior, which often assume flat sensory landscapes or rely heavily on visual coordination, our method integrates domain-specific constraints unique to the deep sea. Moreover, our computational platform allows for iteration, scaling and future adaptation with minimal overhead.

When compared to other modeling approaches, our model integrates a broader and more environmentally contextual range of parameters. Classical models such as the Vicsek model or Boids-based frameworks primarily focus on alignment and cohesion in open, homogeneous environments (Ginelli 2016; Charlwood 2023; Wang et al., 2023; Hengstebeck et al., 2024). These models rarely incorporate the environmental physics of the medium in which the swarm operates. In the ocean, particularly at depth organisms contend with non-negligible shear forces and hydrostatic pressures orders of magnitude higher than those at the surface. Few models explicitly simulate the impact of pressure on signaling efficiency or account for the influence of fluid dynamics on group cohesion. Additionally, the implementation of predator-avoidance behavior without vision and the simulation of microbial growth via DLA mechanisms extend our scope to multiple scales of biological complexity.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Our simulations are constrained to two-dimensional domains which do not fully reflect the three-dimensional spatial behavior of real swarms or microbial colonies. Still, the absence of real-world calibration data means that parameter values like the coefficients for communication decay or shear strength are approximations based on literature or heuristic reasoning. We assume homogeneity across agents, meaning all individuals have identical sensory, motility and response properties. This neglects biological factors like variability in size, metabolic rate or communication capability. Finally, microbial growth is modeled purely by diffusion-limited aggregation, omitting factors like nutrient gradients, surface topology or biofilm feedback mechanisms. Recognizing these boundaries is essential for contextualizing the results and framing them within the scope of theoretical exploration rather than predictive ecology.

Our framework can serve as a springboard for multiple experimental and theoretical extensions. In applied marine biology, our model could be used to formulate testable hypotheses about animal behavior at depth, such as predicting swarm dispersal thresholds under changing pressure conditions. In microbial ecology, the colony growth model may inform expectations about spatial structure in vent-associated communities or sediment biofilms. Future versions of the model could incorporate heterogeneous agents, layered sensory modalities or real topographical features extracted from bathymetric data. Another direction would be to simulate variable lighting conditions to model diel vertical migrations or phototactic behaviors. From a physics standpoint, coupling agent behavior to Navier-Stokes solvers would allow for direct fluid-swarm interaction simulations in time-varying flow fields. In robotics, our insights could inspire algorithms for autonomous underwater vehicles operating in communication-limited environments. Additionally, parameter sweeps could be used to define stability regimes, phase transitions or bifurcation points in swarm behavior, aiding in the construction of predictive phase diagrams. Specific experiments could test predictions such as reduced polarity at depth or increased curvature in escape trajectories. In terms of data generation, the simulation engine could be adapted to produce synthetic datasets for training machines learning algorithms on swarm recognition, motion prediction or anomaly detection.

In conclusion, we addressed the question: how do physical constraints typical of deep-sea environments alter the collective dynamics of active biological agents? By modeling pressure, signal decay, fluid shear and limited sensory perception, our simulations showed that these constraints systematically reduce cohesion, alignment and responsiveness, while increasing variability, fragmentation and curvature. This suggests that environmental factors like depth, pressure, turbulence, and communication efficiency can profoundly influence the movement and coordination of biological agents in inaccessible ecosystems, offering a reproducible framework for advancing the biophysical understanding of collective life in extreme environments.

Authors' contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Acinas, Silvia G., Pablo Sánchez, Guillem Salazar, Francisco M. Cornejo-Castillo, Marta Sebastián, Ramiro Logares, Marta Royo-Llonch, et al. "Deep ocean metagenomes provide insight into the metabolic architecture of bathypelagic microbial communities." Communications Biology 4, no. 604 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Balan, Raluca M., Jingyu Huang, Xiong Wang, Panqiu Xia, and Wangjun Yuan. “Gaussian Fluctuations for the Wave Equation under Rough Random Perturbations.” Stochastic Processes and Their Applications 182 (April 2025): 104569. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Peter G., Edward T. Peltzer, and Kathryn Lage. “Life at Low Reynolds Number Re-Visited: The Efficiency of Microbial Propulsion.” Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 185 (2022): 103790. [CrossRef]

- Burford, Benjamin P., and Bruce H. Robison. “Bioluminescent Backlighting Illuminates the Complex Visual Signals of a Social Squid in the Deep Sea.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, no. 15 (2020): 8524–8531. [CrossRef]

- Cavagna, Andrea, Antonio Culla, Xiao Feng, Irene Giardina, Tomas S. Grigera, Willow Kion-Crosby, Stefania Melillo, et al. "Marginal speed confinement resolves the conflict between correlation and control in collective behaviour." Nature Communications 13, no. 2315 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Charlwood, J. D. “Swarming and Mate Selection in Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae).” Journal of Medical Entomology 60, no. 5 (2023): 857–864. [CrossRef]

- Clusella, Pau, and Romualdo Pastor-Satorras. “Phase Transitions on a Class of Generalized Vicsek-like Models of Collective Motion.” Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 31, no. 4 (2021): 043116. [CrossRef]

- DeLeo, Danielle M., and Heather D. Bracken-Grissom. “Bioluminescence and Environmental Light Drive the Visual Evolution of Deep-Sea Shrimp (Oplophoroidea).” Communications Biology 8 (2025): 213. [CrossRef]

- Du, Jianghui, Brian A. Haley, James McManus, Patrick Blaser, Jörg Rickli and Derek Vance. "Abyssal seafloor as a key driver of ocean trace-metal biogeochemical cycles." Nature 642 (2025): 620–627. [CrossRef]

- Gal, Asaf, and Daniel J. C. Kronauer. "The emergence of a collective sensory response threshold in ant colonies." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, no. 23 (2022): e2123076119. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Jie, Ziming Wang, Wenjie Deng, Boxuan Sa, Xiaoxia Chen, Ruanhong Cai, Yi Yan, Nianzhi Jiao, Elaine Lai-Han Leung, Di Liu, and Wei Yan. “Improved Resolution of Microbial Diversity in Deep-Sea Surface Sediments Using PacBio Long-Read 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing.” Environmental Microbiology (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ginelli, Francesco. “The Physics of the Vicsek Model.” European Physical Journal Special Topics 225 (2016): 2099–2117. [CrossRef]

- Hengstebeck, Cole, Peter Jamieson, and Bryan Van Scoy. “Extending Boids for Safety-Critical Search and Rescue.” Franklin Open 8 (September 2024): 100160. [CrossRef]

- Khona, Mehul, Surya Chandra, and Ila Fiete. "Global modules robustly emerge from local interactions and smooth gradients." Nature 640 (2025): 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Kunze, Eric. “Fluid Mixing by Swimming Organisms in the Low-Reynolds-Number Limit.” Journal of Marine Research 69, no. 4 (2011). https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/journal_of_marine_research/319.

- Lomidze, Levan, David J. Knudsen, Johnathan Burchill, Alexei Kouznetsov, and Stephan C. Buchert. “Calibration and Validation of Swarm Plasma Densities and Electron Temperatures Using Ground-Based Radars and Satellite Radio Occultation Measurements.” Radio Science 52, no. 10 (2017): 1333–1345. [CrossRef]

- Maity, Samadarshi, and Alexandre Morin. "Spontaneous demixing of binary colloidal flocks." Physical Review Letters 131, no. 178304 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Martini, Séverine, and Steven H. D. Haddock. “Quantification of Bioluminescence from the Surface to the Deep Sea Demonstrates Its Predominance as an Ecological Trait.” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 45750. [CrossRef]

- Milke, Felix, Jens Meyerjürgens and Meinhard Simon. "Ecological mechanisms and current systems shape the modular structure of the global oceans’ prokaryotic seascape." Nature Communications 14, no. 6141 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, Marina, Hanno Hildenbrandt, Daniel W. E. Sankey, Steven J. Portugal, and Charlotte K. Hemelrijk. "Self-organization of collective escape in pigeon flocks." PLoS Computational Biology 18, no. 1 (2022): e100977. [CrossRef]

- Pedrami, R., and B. W. Gordon. “Control and Cohesion of Energetic Swarms.” In Proceedings of the 2008 American Control Conference, 11–13 June 2008, Seattle, WA. IEEE, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Jie, Wen-Xu Wang, Gang Yan, and Bing-Hong Wang. "Diffusion-Limited Aggregation on a Directed Small World Network." arXiv preprint arXiv:physics/0602178 (2006). https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0602178.

- Román, Sara, Rüdiger Ortiz-Álvarez, Chiara Romano, Emilio O. Casamayor, and Daniel Martín. “Microbial Community Structure and Functionality in the Deep Sea Floor: Evaluating the Causes of Spatial Heterogeneity in a Submarine Canyon System (NW Mediterranean, Spain).” Frontiers in Marine Science 6 (2019): 108. [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, Raphaël, and Orit Peleg. "Chimera states among synchronous fireflies." Science Advances 8, no. 46 (2022): eadd6690. [CrossRef]

- Sayin, Sercan, Einat Couzin-Fuchs, Inga Petelski, Yannick Günzel, Mohammad Salahshour, Chi-Yu Lee, Jacob M. Graving, et al. "The behavioral mechanisms governing collective motion in swarming locusts." Science 387, no. 6737 (2025): 995–1000. [CrossRef]

- Sharoni, Shlomit and Itay Halevy. "Rates of seafloor and continental weathering govern Phanerozoic marine phosphate levels." Nature Geoscience 16 (2023): 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, Christian, Mehdi Boutrif, Marc Garel, Rita R. Colwell, and Jody W. Deming. “Prokaryotic Responses to Hydrostatic Pressure in the Ocean—A Review.” Environmental Microbiology 15, no. 5 (2013): 1262–1274. [CrossRef]

- Valdes, Paul J., Christopher R. Scotese, and Daniel J. Lunt. “Deep Ocean Temperatures Through Time.” Climate of the Past 17, no. 4 (2021): 1483–1506. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaocheng, Hui Zhao, and Li Li. “An Improved Vicsek Model of Swarms Based on a New Neighbor Strategy Considering View and Distance.” Applied Sciences 13, no. 20 (2023): 11513. [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, Brett, Jessica Palmeri, Patrick Flannery, Lydia Fregosi, Cassandra Donatelli, and Mackenzie E. Gerringer. “Swimming Kinematics of Deep-Sea Fishes.” Journal of Fish Biology 106, no. 3 (2025): 805–822. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chenru, Qian Liu, Xianrong Li, Min Wang, Xiaoshou Liu, Jinpeng Yang, Jishang Xu, et al. “Spatial Patterns and Co-Occurrence Networks of Microbial Communities Related to Environmental Heterogeneity in Deep-Sea Surface Sediments Around Yap Trench, Western Pacific Ocean.” Science of the Total Environment 759 (2021): 143799. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

was added to the velocity update, scaled by a constant . These rules jointly dictated the local interactions that govern emergent group alignment, cohesion and trajectory smoothing. With this mechanism, each agent could both align with neighbors and avoid crowding, providing a baseline for comparison under additional environmental influences.

was added to the velocity update, scaled by a constant . These rules jointly dictated the local interactions that govern emergent group alignment, cohesion and trajectory smoothing. With this mechanism, each agent could both align with neighbors and avoid crowding, providing a baseline for comparison under additional environmental influences.

, added to the velocity

before normalization, with to simulate background turbulence (Balan et al., 2025). By combining shear and stochastic forces, this method provided a scalable approach to investigating how hydrodynamic disturbances affect swarm integrity at various depths.

, added to the velocity

before normalization, with to simulate background turbulence (Balan et al., 2025). By combining shear and stochastic forces, this method provided a scalable approach to investigating how hydrodynamic disturbances affect swarm integrity at various depths.  was initialized with a seed at the center

was initialized with a seed at the center  and random walkers were introduced at lattice boundaries. Each walker followed a discrete random walk governed by:

and random walkers were introduced at lattice boundaries. Each walker followed a discrete random walk governed by:

, to evaluate escape efficiency and group fragmentation. This simulation explored

how non-visual strategies like local repulsion could enable swarm survival in

visually inaccessible environments.

, to evaluate escape efficiency and group fragmentation. This simulation explored

how non-visual strategies like local repulsion could enable swarm survival in

visually inaccessible environments.

is the velocity vector,

is the velocity vector, is the acceleration vector,

is the acceleration vector,