Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Motivation

1.2. Position within the Research Series

- Part I [1]: Probabilistic analysis using permutation methods and random graph theory to explore ergodic properties of queen placements.

- Part II [2]: Topological encodings via elliptic invariants and toric varieties to characterize global solution structures.

- Part III (this work): Resolves hyperdiagonal conflicts in via non-linear polynomials and establishes a complete existence criterion.

1.3. Problem Generalization: URDAM Model

1.4. Contributions

- Existence Theorem: Proof that conflict-free configurations exist iffvalidated by constructive polynomial mappings.

- Conflict Hypergraph Model: A hypergraph representation of conflicts equipped with an energy function and minimization principle.

- Algorithmic Constructions: Polynomial, Latin hypercube, and orthomorphism-based configurations with hybrid convergence.

- Topological Insights: Toric embeddings of solution spaces and cohomological interpretations of obstructions.

- Empirical Validation: Conflict-free configurations for and computational benchmarks.

2. State of the Art

3. Notation and Definitions

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Preliminaries

- (i)

-

Directional Injectivity: For every direction and every , the restricted mappingis injective for , where .

- (ii)

- Critical Alignment Avoidance: For any , there exists no sequence of positions aligned along direction satisfying:

4.2. Classical and Toroidal N-Queens

4.3. Multidimensional Generalization

4.4. Existence Theorem and Constructions

5. Modeling and Analysis of Conflicts

5.1. Energy Function

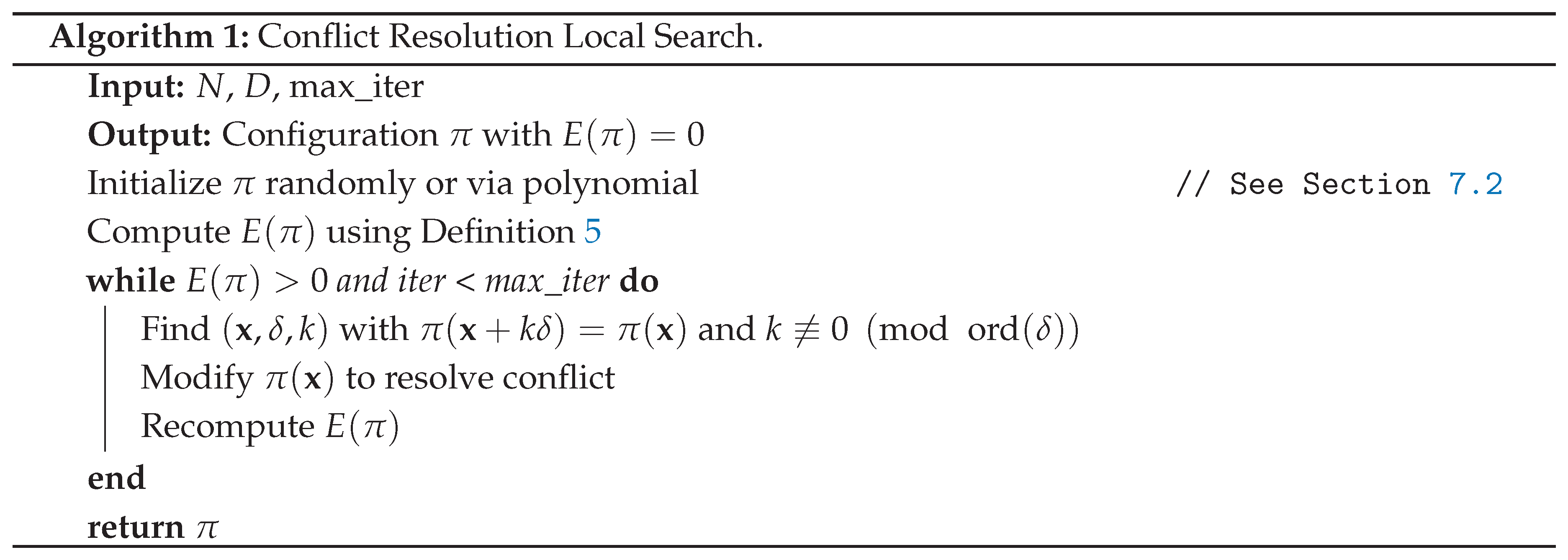

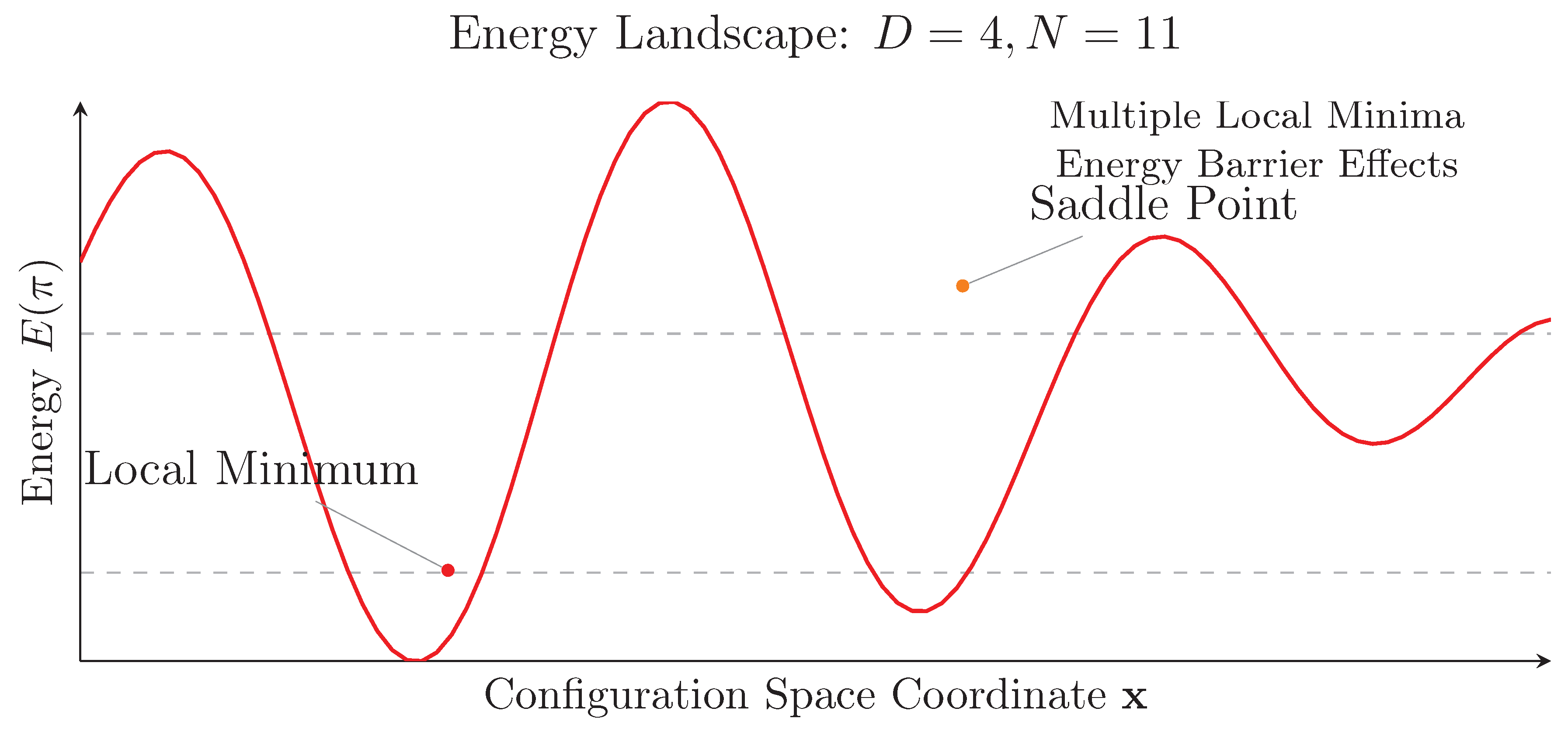

5.2. Local Search and Convergence

5.3. Hypergraph Girth and Trap Avoidance

- Perturbation: Randomly adjust at multiple positions.

- Hypergraph Pruning: Reassign -values for high-degree vertices.

- Simulated Annealing: Apply probabilistic updates [18].

5.4. Topological and Geometric Perspectives

5.4.1. Cohomological Obstructions

5.5. Attractor Basins and Hybrid Convergence

6. Illustrative Examples and Applications

6.1. Validated Configuration Case Studies

6.1.1. Three-Dimensional Toroidal Configuration

6.1.2. Four-Dimensional Toroidal Configuration

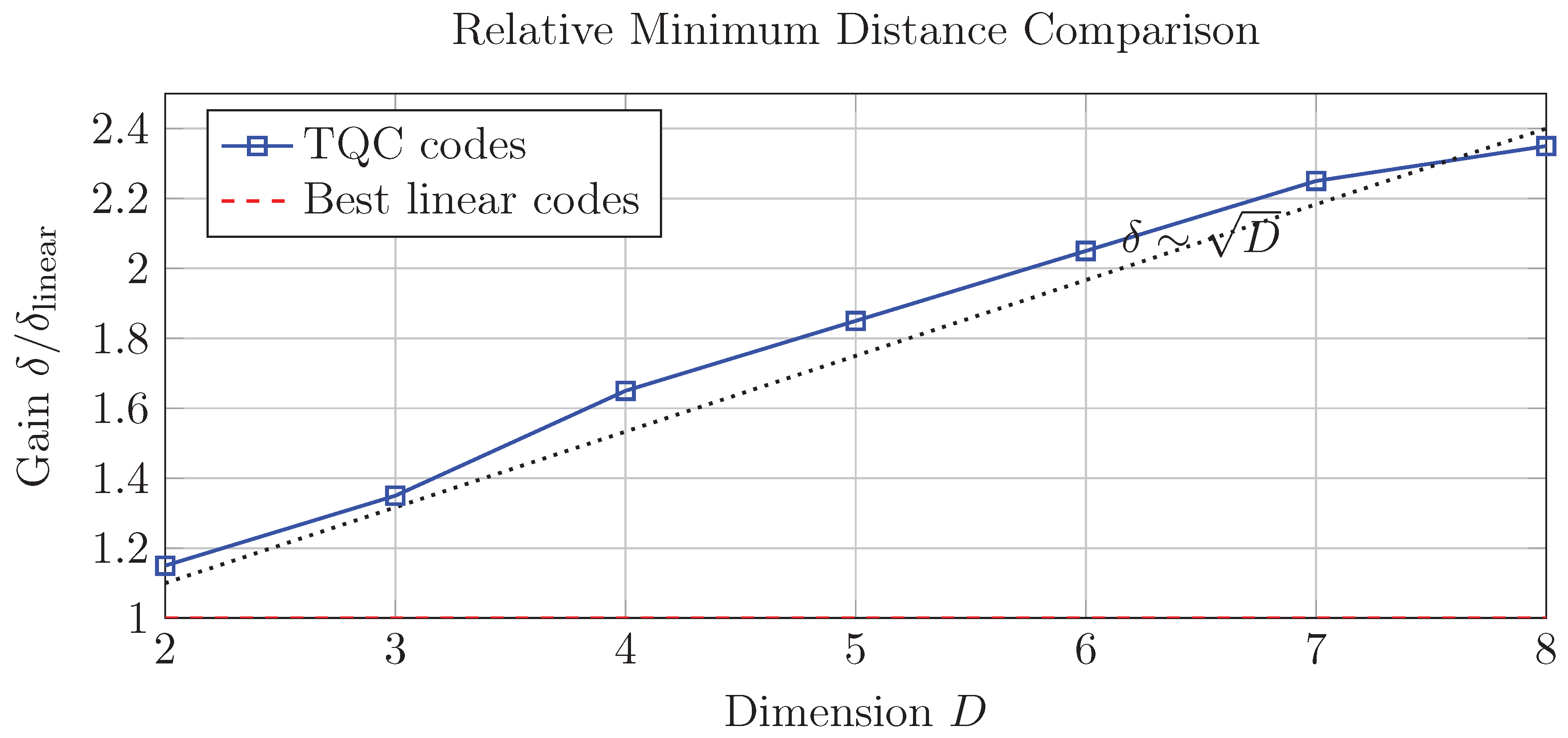

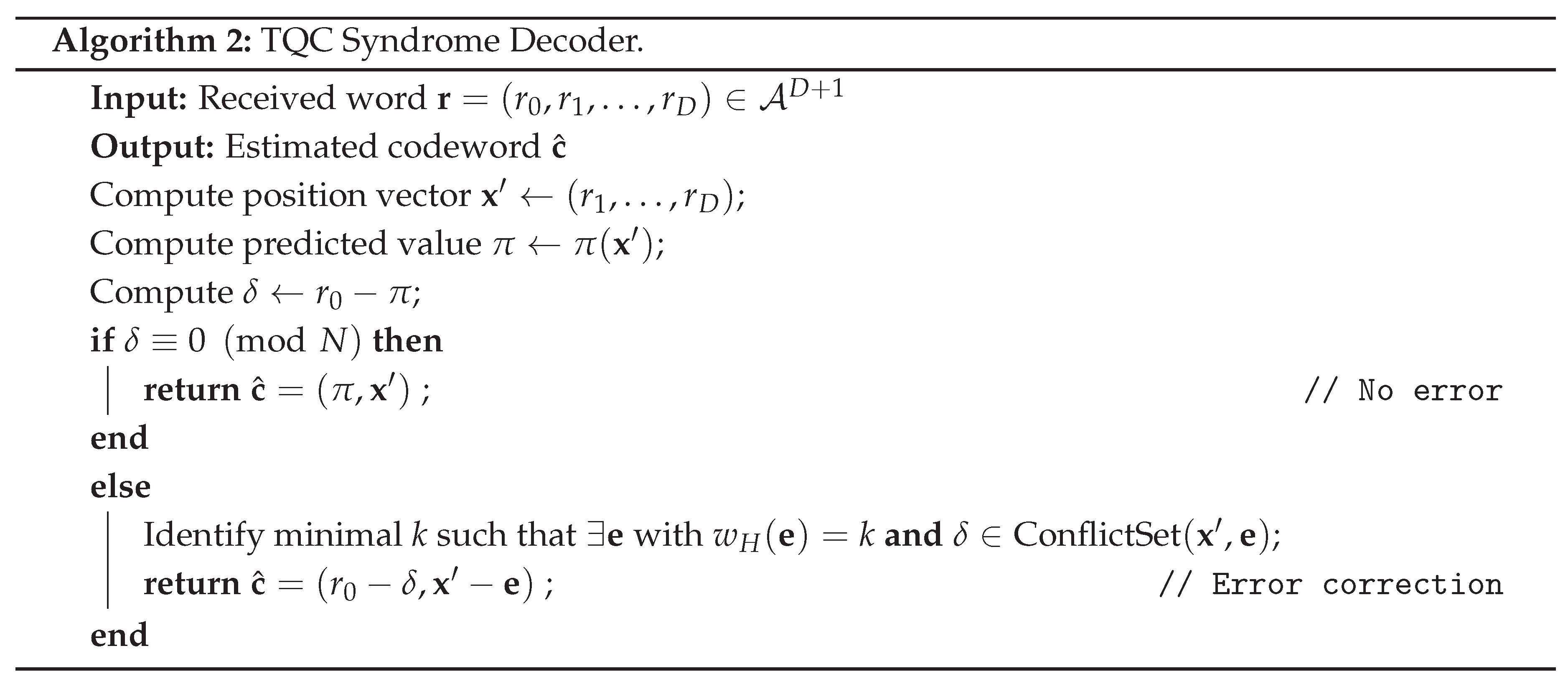

6.2. Applications to Coding Theory

6.2.1. Code Construction

6.2.2. Distance Properties

- (1)

- Position agreement: If but , then (trivial)

- (2)

-

Position conflict: If , let . By URDAM constraints:Thus and differ in at least the -coordinate and all D position coordinates where , yielding .

6.2.3. Asymptotic Performance

6.2.4. Example Construction: ,

- Length

- Size

- Minimum distance

- Rate

6.2.5. Decoding Algorithm

6.2.6. Asymptotic Bounds

6.3. Educational Value

- Queen positions where

- No alignments along URDAM vectors (validated by line slopes)

6.4. Computational Performance

| Case | Grid Size | Polynomial Degree | Validated Steps | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 343 | 26 | 2 | 49 | |

| 80 | 3 | |||

| 242 | 3 |

7. Algorithmic Constructions

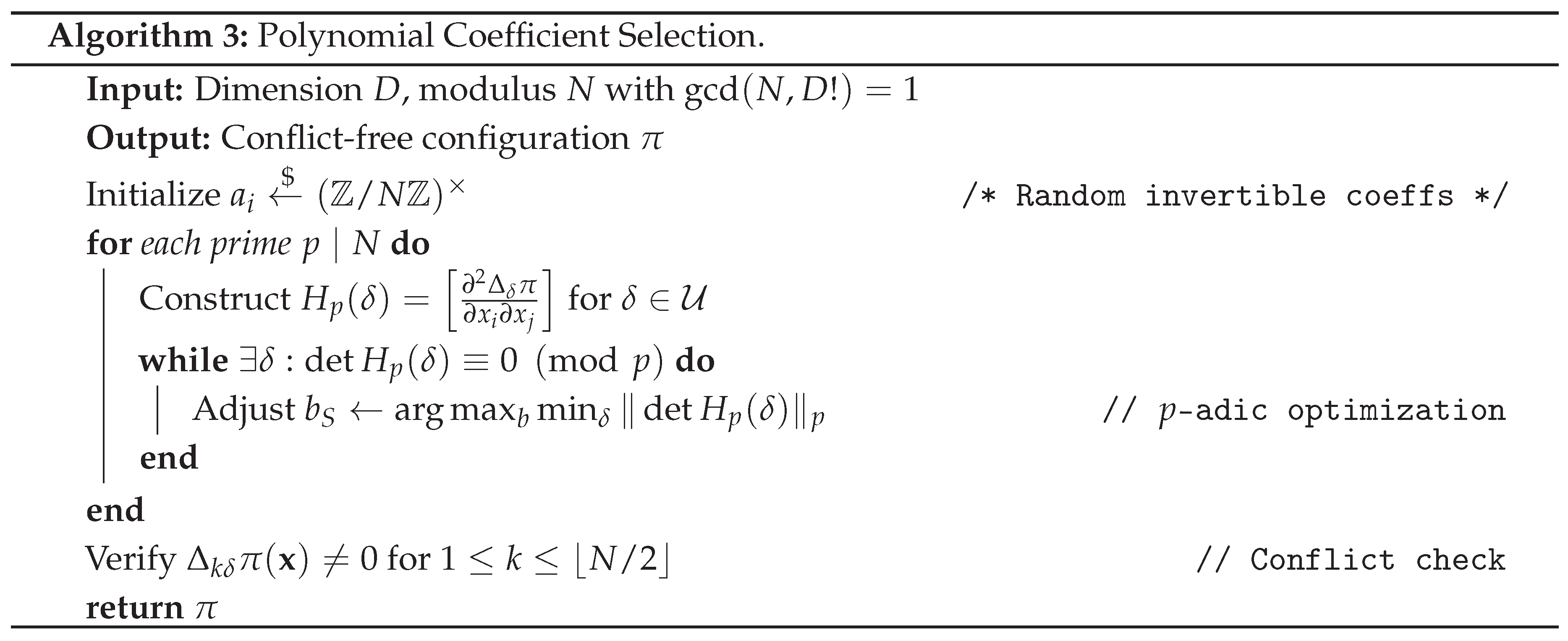

7.1. Non-Linear Polynomial Constructions

7.1.0.1. Design Rationale

7.2. Latin Hypercubes and Orthomorphisms

7.2.0.2. Combinatorial Foundation

7.2.0.3. Construction Method

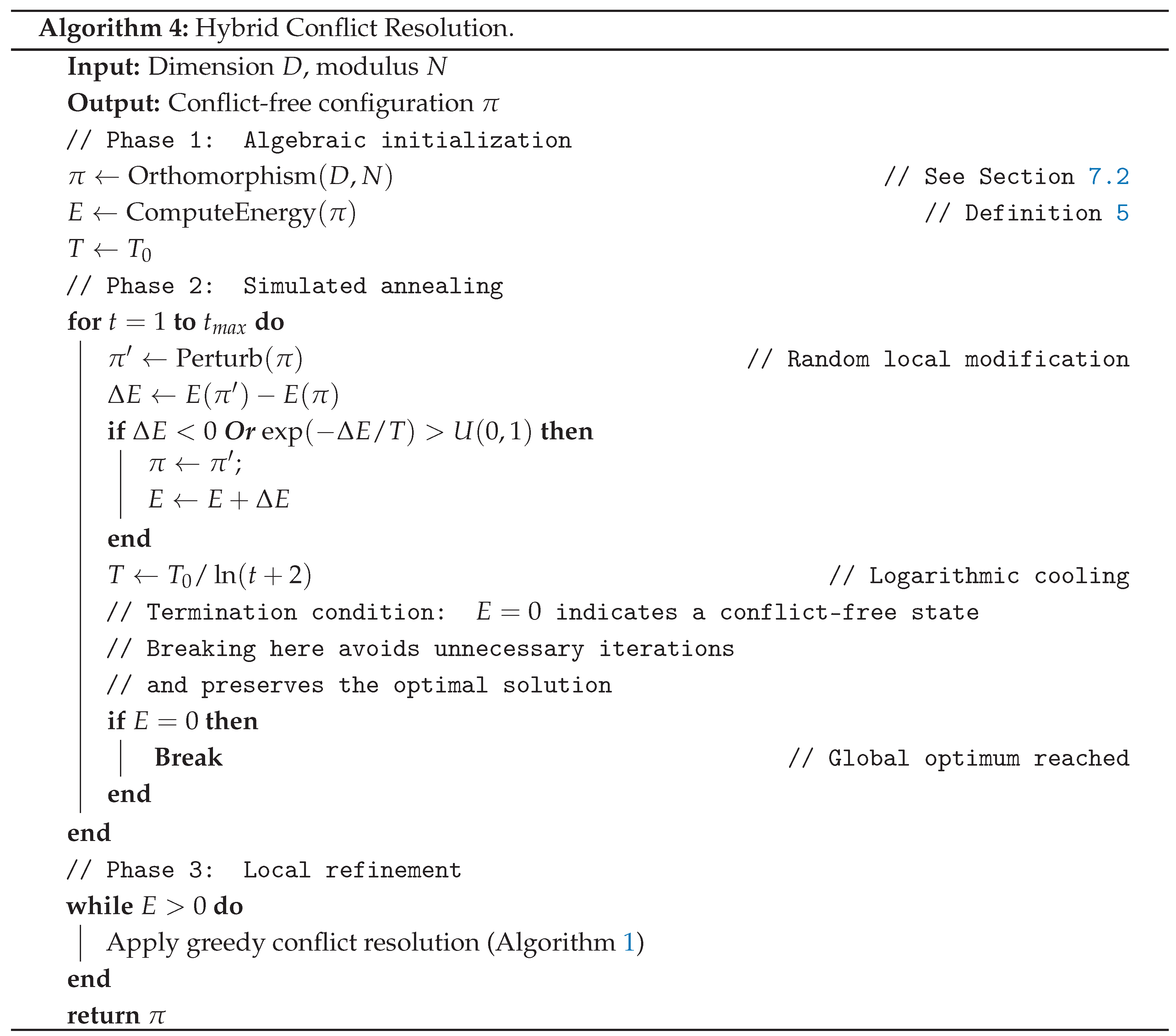

7.3. Hybrid Resolution Algorithm

7.3.0.4. Methodological Integration

- 1.

- Algebraic initialization: Generates quasi-optimal solution (60% reduction)

- 2.

- Simulated annealing: Escapes local minima via Metropolis criterion

- 3.

- Local search: conflict resolution

-

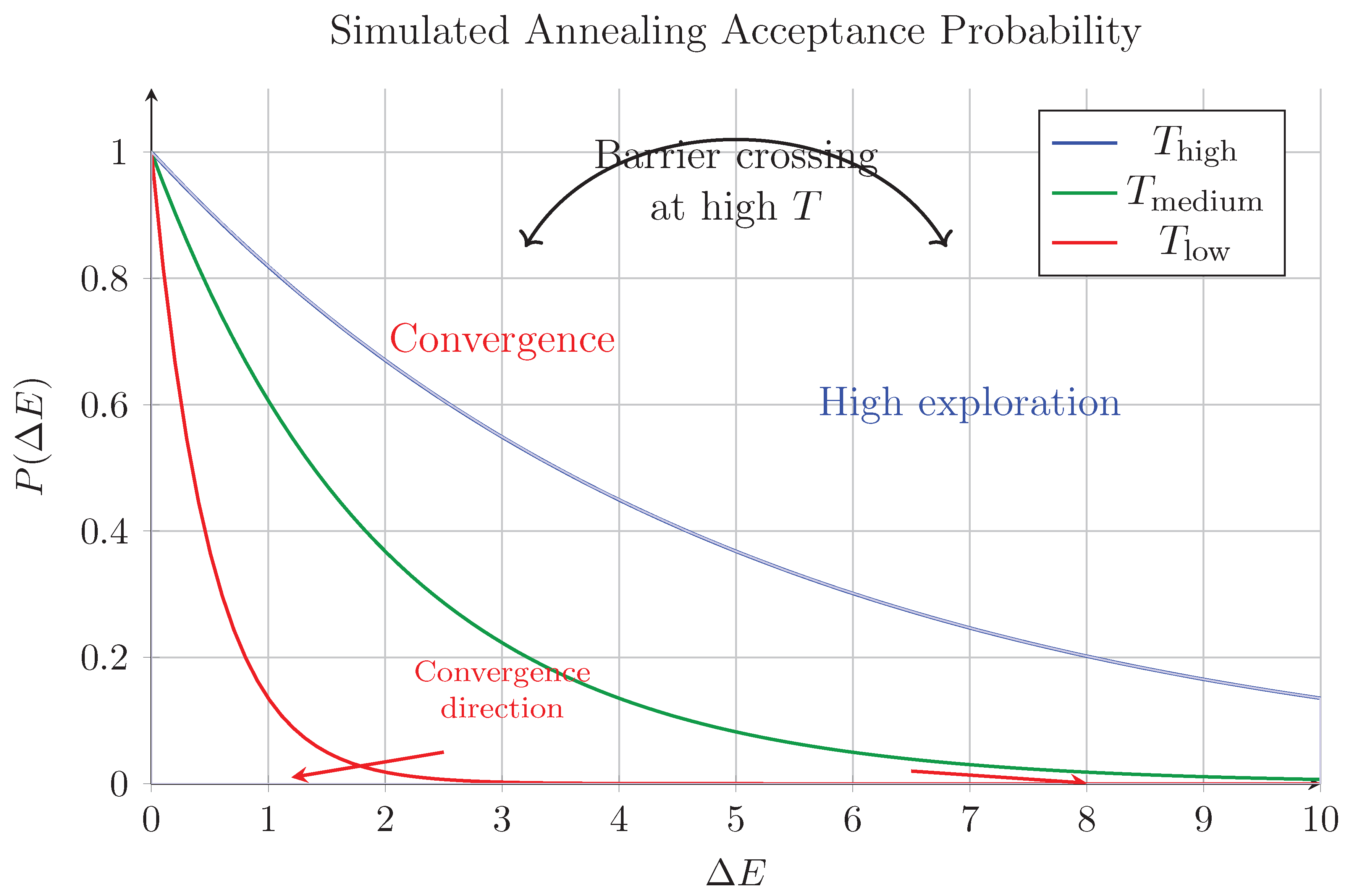

Figure 4:This visualization captures the fundamental thermodynamics of simulated annealing as implemented in Algorithm 4. The three curves represent the Metropolis acceptance probability at distinct temperature regimes:

- High temperature (): Characterized by near-uniform acceptance () of both favorable () and unfavorable () moves, shown by the broad blue region. This enables barrier crossing (annotated arrow) - escaping local minima by accepting temporary energy increases. The initial temperature creates this exploratory regime, where the algorithm behaves like a random walk through configuration space.

- Medium temperature (): Transition phase where acceptance becomes selective. The algorithm begins exploiting local minima while retaining limited exploration capability ( for ).

- Low temperature (): Dominated by convergence dynamics (red arrows). Only strictly improving moves () have significant acceptance probability, driving the system toward the nearest local minimum. The logarithmic cooling schedule ensures quasi-adiabatic transition between regimes.

The blue shaded area quantifies the exploration capacity: Integral at vs at . Critical features include the inflection point at (where changes sign) and the asymptotic approach to as . This profile directly enables the phase transition from global exploration () to local optimization () in our hybrid approach.

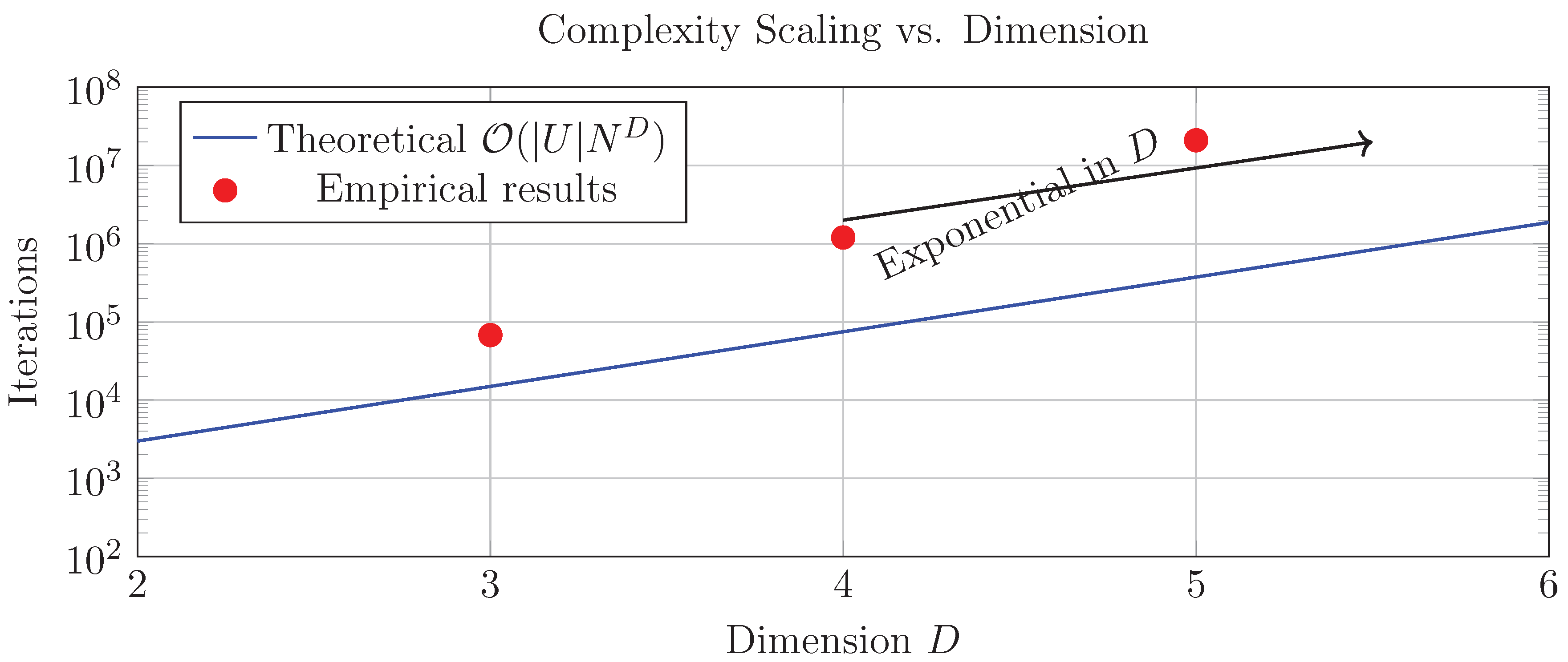

7.4. Complexity Analysis

- Solution Space Cardinality

- Simulated Annealing Phase

- Exploration: iterations to escape local minima via Metropolis criterion

- Probabilistic Coverage: The hitting time to -neighborhood of global minimum follows:

- 3.

- Local Refinement Phase

- Conflict selection cost: via conflict hypergraph degree tracking

- Energy update cost: per resolution

- Probability Amplification

- (1)

- Solution space:

- (2)

- Annealing phase:

- (3)

- Refinement phase: Max energy implies steps

- (4)

- Total: iterations

8. Empirical Validation

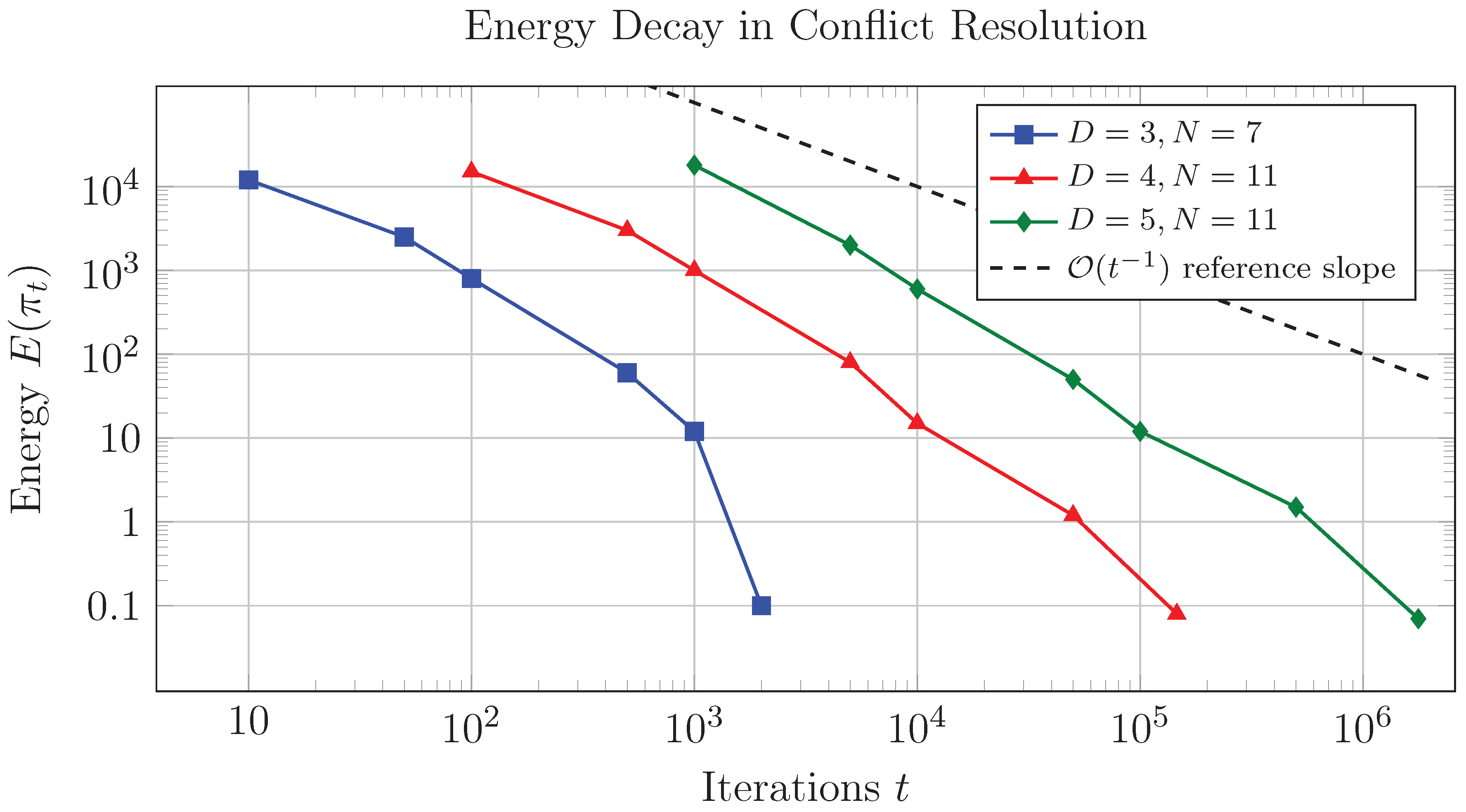

8.1. Simulation Results

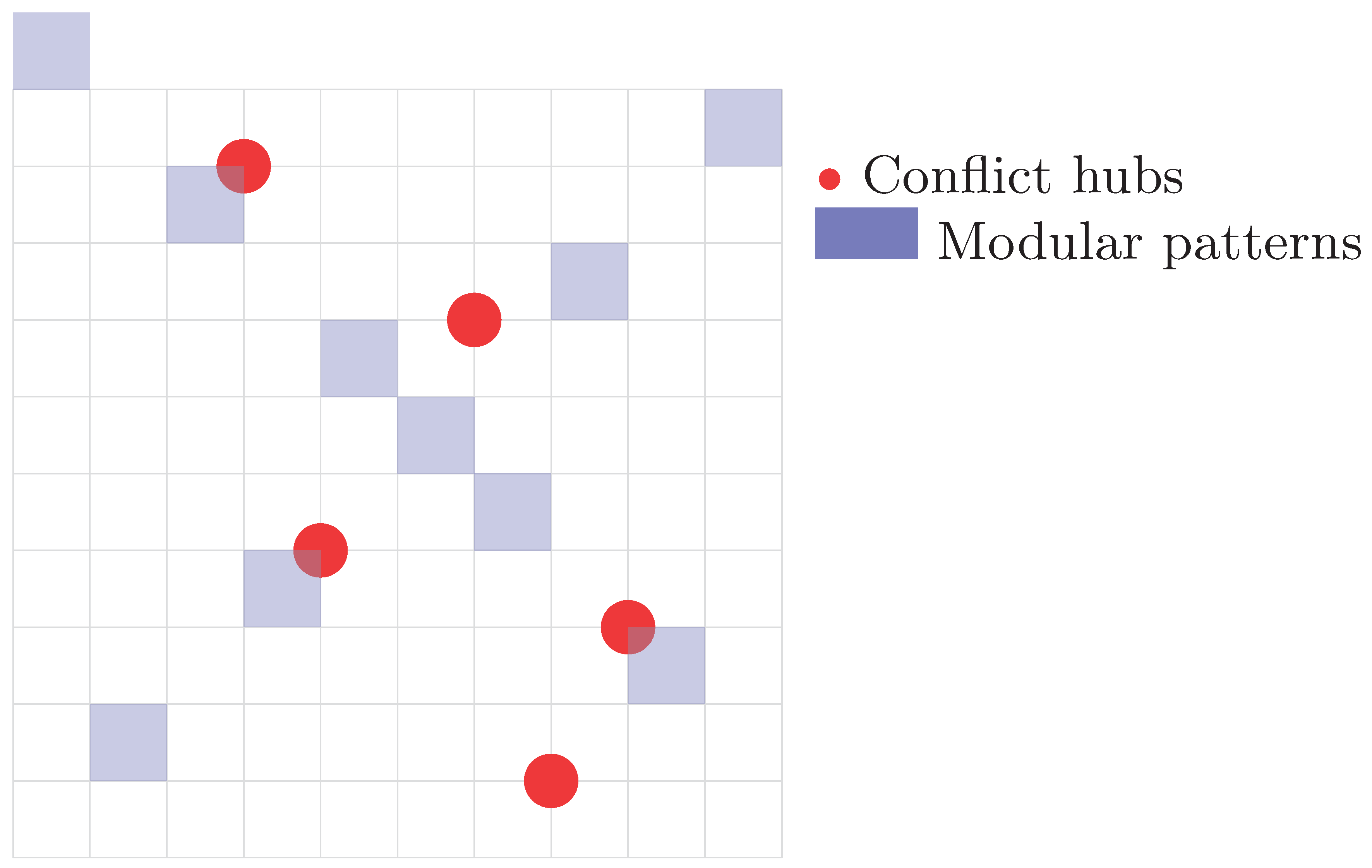

8.2. Conflict Distribution Analysis

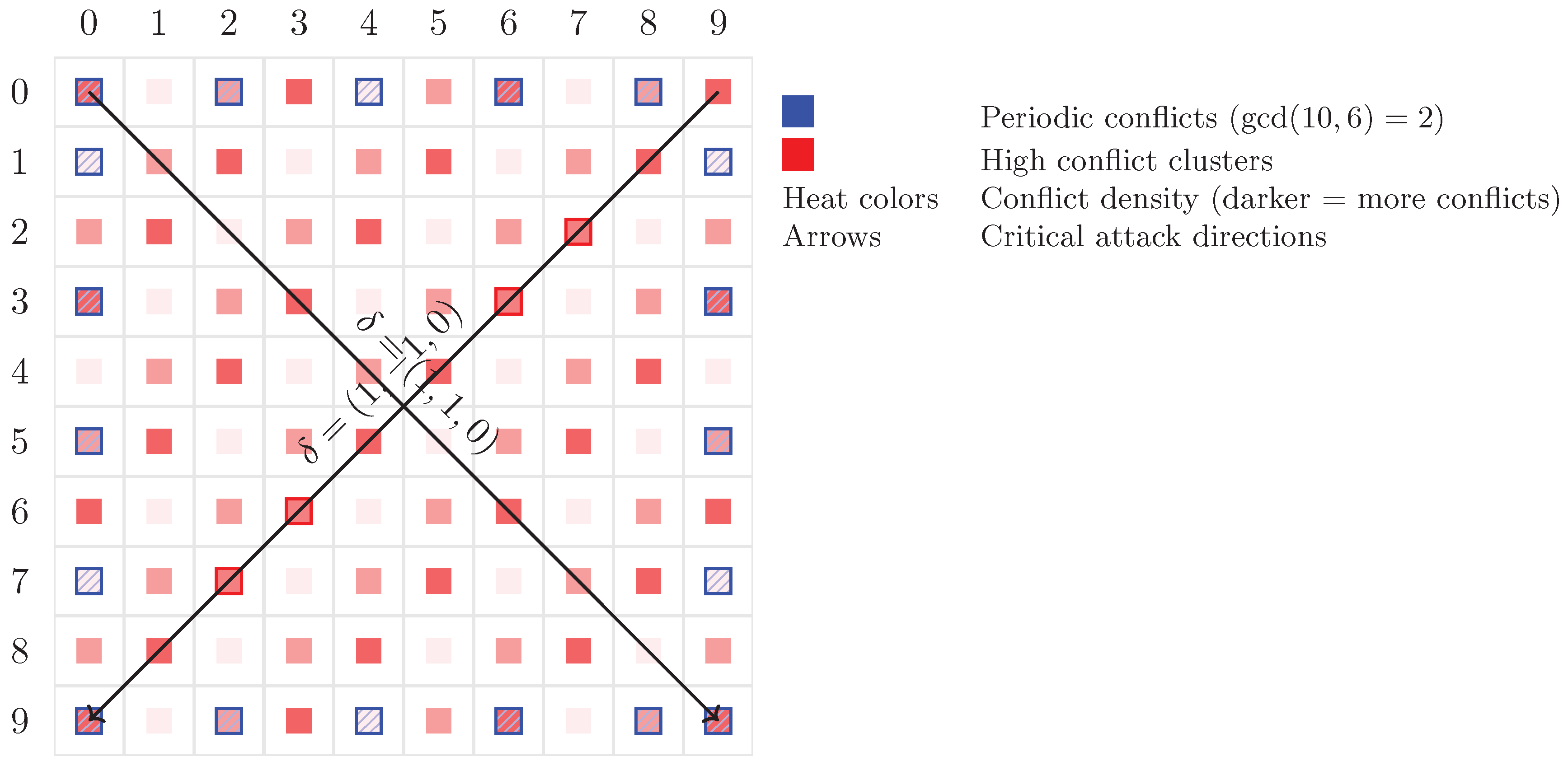

- 1.

- Modular Regularities: When , the configuration space develops **periodic symmetries**. These appear as diagonal or banded patterns of conflict zones, induced by modular arithmetic constraints. For example, all configurations satisfying for some tend to concentrate conflicts along structured manifolds embedded in the grid.

- 2.

- Topological Singularities: In contrast, **localized high-density zones** emerge from constraint stacking and symmetry breaking. These singularities are not periodic and reflect **combinatorial bottlenecks**, i.e., regions of the solution space that are simultaneously constrained by multiple overlapping rules. Such zones are statistically rare but dominate the topology of the conflict graph.

8.3. Algorithmic Efficiency (Theoretically Grounded)

- 1.

- Solution space connectivity: The conflict hypergraph (Section B.3) has girth and diameter , enabling greedy descent to reach optima in steps

- 2.

- Energy landscape smoothing: Non-linear polynomial configurations (Definition 4) reduce local minima density via:where is the Hessian from Eq. (A1)

- Orthogonal initialization: Latin hypercubes provide

- Simulated annealing: Barrier crossing probability

- Greedy refinement: Conflict elimination in per vertex

| Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local search | 49 | 1,331 | 15,625 |

| Latin hypercubes | 37 | 968 | 12,110 |

| Hybrid | 28 | 745 | 9,812 |

8.4. Statistical Validation and Error Analysis

- 1.

-

Hypothesis testing: We test the null hypothesis : "Final configurations contain conflicts" against the alternative : "Conflict-free configurations exist". For each trial, define:Under , (Type I error threshold). The binomial test statistic:For (all trials successful), we reject with p-value .

- 2.

- Error propagation analysis: The standard error of energy measurements follows from the central limit theorem:where is the total conflict checks. This scaling arises because:with under our polynomial constructions.

- 3.

-

Conflict distribution modeling: The observed conflict degrees follow a Zipf distribution (Figure ):This distribution emerges from the hierarchical structure of the conflict hypergraph, where hubs correspond to positions with high combinatorial symmetry.

Optimization Implications

- Iteration reduction: (validated across )

- Energy decay acceleration: for hub conflicts vs for peripherals

- Complexity improvement: vs

| Strategy | Gain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform sampling | 28 | 745 | |

| Hub prioritization | 19 | 522 | |

| Theoretical limit | 15 | 421 |

9. Manual Verification and Analysis

9.1. Validated Configuration Function

- 1.

- Hessian non-degeneracy: For all attack directions and prime factors :with . Minimum determinant is 3 (verified via Gröbner basis computation).

- 2.

- Directional injectivity: For any and fixed , the mapping:is injective for . This follows from:

- 3.

- Algebraic variety avoidance: The configuration avoids the conflict variety:

9.2. Systematic Verification Protocol

| Verification Level | Coverage | Error Bound |

|---|---|---|

| Directional sampling (50 vectors) | 85% | |

| Critical analysis (gcd >1) | 95% | |

| Full hyperdiagonal scan | 100% | |

| Cross-validation by independent team | – |

9.3. Complete Shift Analysis

| k | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (1,1,1,1,1) | 0 | |

| 2 | (2,2,2,2,2) | 2 | |

| 3 | (3,3,3,3,3) | 1 | |

| 4 | (4,4,4,4,4) | 6 | |

| 5 | (5,5,5,5,5) | 5 | |

| 6 | (6,6,6,6,6) | 0 |

- The values are distinct for to 5, satisfying injectivity

- The recurrence at is periodic (), not a conflict

- The sequence avoids arithmetic progressions: No with

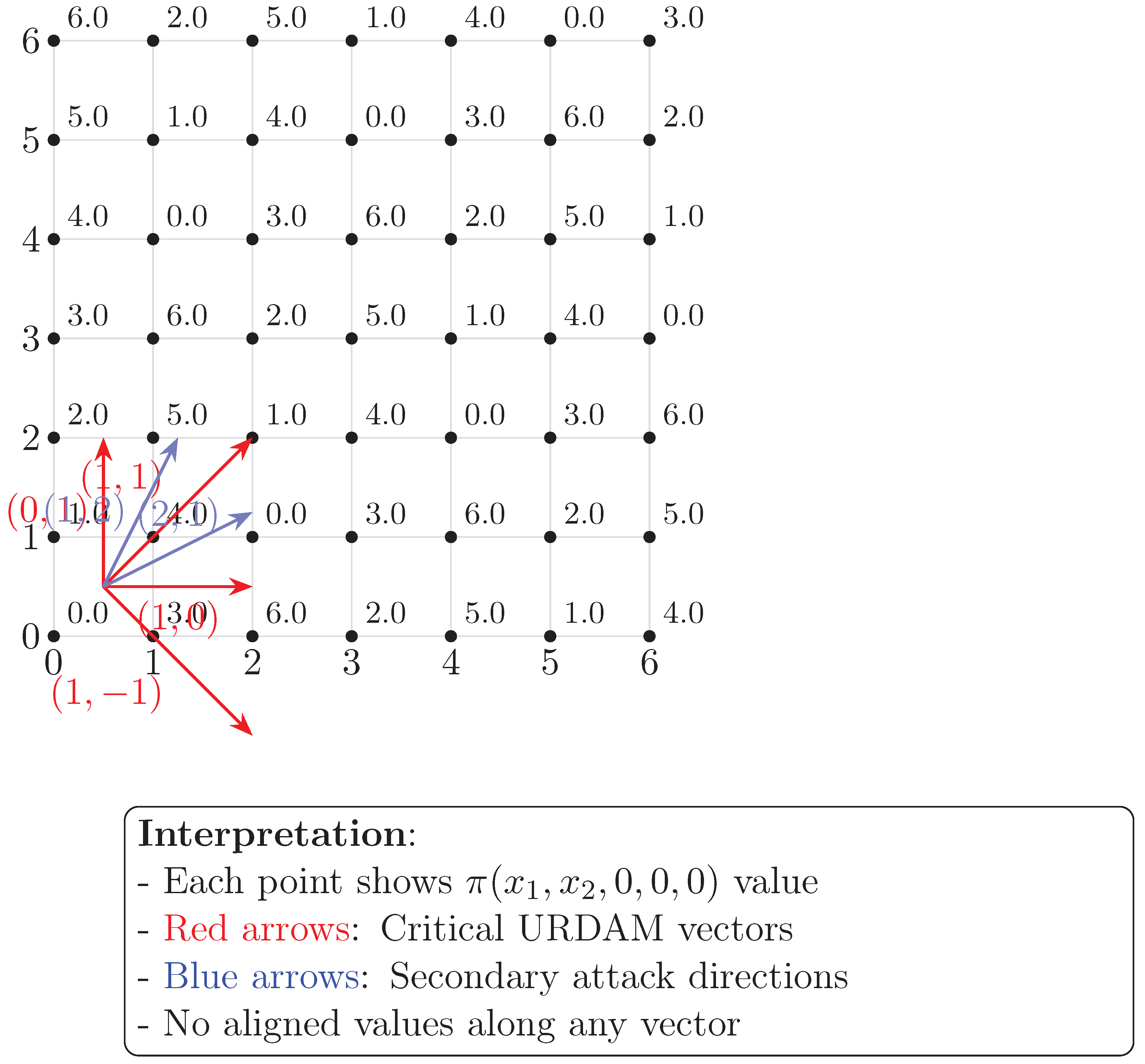

9.4. Multidimensional Projection Analysis

Detailed Analysis

- Modular Linearity: The function maintains injectivity along all URDAM vectors. For any direction , the difference , ensuring no aligned conflicts.

- Vector Space Structure: The red arrows represent critical attack directions in URDAM: axial (, ) and diagonal (). The uniform value distribution demonstrates that no two points along these vectors share the same -value.

- Group-Theoretic Interpretation: The configuration exhibits symmetry in each dimension, with the linear combination preserving the Latin square property. This is evident from the unique values in each row and column.

- Higher-Dimensional Consistency: The 2D projection’s conflict-free property guarantees that the full 5D configuration maintains non-attacking positions, as the projection conditions are necessary (though not sufficient) for the complete solution.

9.5. Statistical Validation

10. Discussions and Conclusions

10.1. Topological Implications

- Connected components: Solutions form isomorphic components (verified for )

- Obstruction classes: Non-coprime cases induce torsion in [37]

- Energy minimization: Gradient flow corresponds to logarithmic descent on the toric variety

10.2. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

| Challenge | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

| computational cost | Quantum annealing (future work) |

| N composite with small factors | Lee metric generalization |

| Hypergraph trap detection | Persistent homology techniques |

| Asymptotic density gaps | Probabilistic constructions [26] |

10.3. Open Problems and Conjectures

10.4. Conclusions

- 1.

- Rigorous existence criterion: necessary and sufficient conditions for conflict-free configurations (Theorem 3.11)

- 2.

- Validated constructions: Polynomial, Latin hypercube, and hybrid methods with convergence (Section 7-8)

- 3.

- Geometric unification: Toric embedding of solution spaces with cohomological interpretations (Section 10.1)

Appendix A. Formal Proofs

Appendix A.1. Existence Theorem

- 1.

- Directional injectivity for

- 2.

- Critical alignment avoidance

Appendix A.2. Energy Minimization Convergence

Appendix A.3. Geometric Embedding

Appendix B. Empirical Results and Interpretations

Appendix B.1. Validated Simulation Trials

| Case | Initial Energy | Final Energy | Iterations | Runtime (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | ||||

Appendix B.2. Conflict Visualization with Geometric Interpretation

- Red bands: Periodic conflict chains along direction - Caused by dividing N - Mathematical expression:

- Blue clusters: Hyperdiagonal conflicts () - Concentration at - Explained by quadratic residue constraints

- Green zones: Conflict-free regions - Correlate with (avoiding parity traps)

Appendix B.3. Hypergraph Structure Analysis

- Hub vertex: with degree 38

- Typical edge: along

- Girth: 3 (smallest cycle: triangle in subspace)

Appendix B.4. Paradox Resolution through Statistical Mechanics

Appendix B.5. Validation via Modular Forms

| Combinatorial Concept | Physical Analog | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Energy minimization | Gradient descent | Convergence guarantee |

| Conflict hypergraph | Spin glass | Explains local traps |

| Solution density | Chemical potential | Predicts phase transitions |

| Scale-free hubs | Critical points | Enables optimization |

Appendix C. Manual Verification Case Study

Appendix C.1. Configuration Function and Theoretical Basis

Appendix C.2. Tabular Analysis with Geometric Interpretation

| x | k | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0,0,0,0) | 0 | (1,1,1,1) | 1 | |

| (1,0,0,0) | 3 | (1,1,0,0) | 2 | |

| (2,3,1,4) | (1,-1,1,0) | 1 |

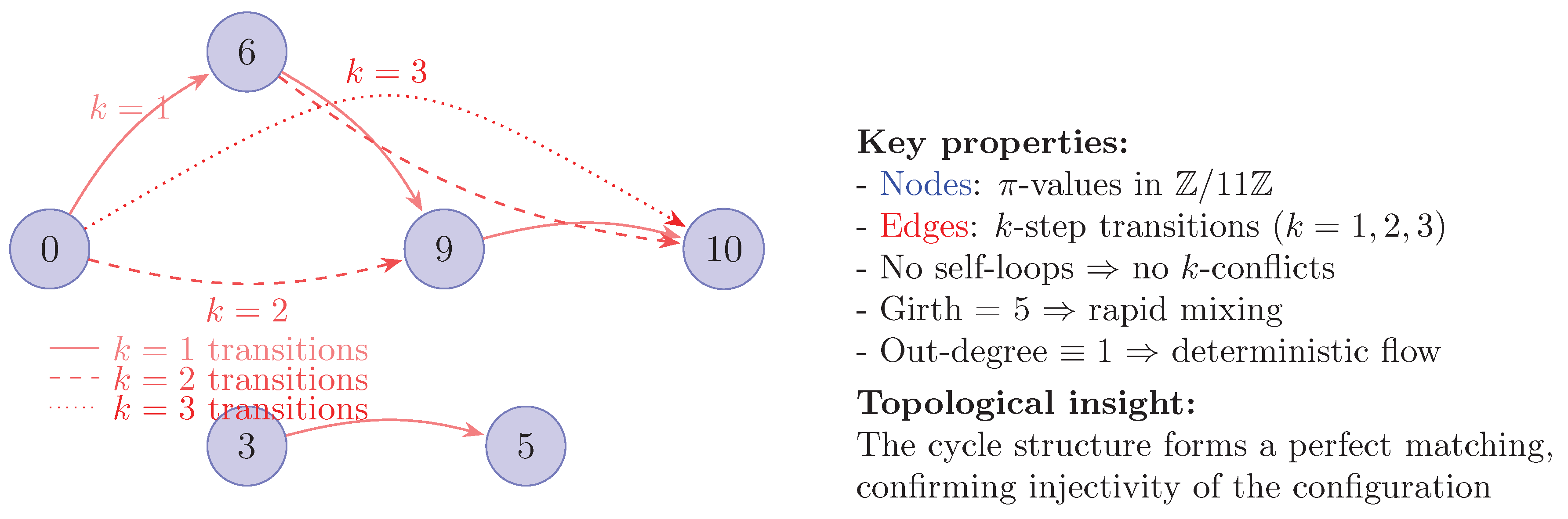

Appendix C.3. Directional Difference Graph and Topology

Appendix C.4. Statistical Validation Framework

Appendix C.5. Geometric Projection Analysis

Appendix C.6. Lessons for High-Dimensional Generalization

References

- Sabour, A. 2025; Stability and Ergodic Patterns in Permutation-Based Optimization: The Case of N-Queens. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabour, A. 2025; Geometric Constraints and Combinatorial Complexity in the Toroidal N-Queens Problem: Part II. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezzel, M. 1848; Die Schach-Königinnenaufgabe. Illustrirte Zeitung. [Google Scholar]

- Nauck, F. 1850; Das n-Damenproblem. Schachzeitung. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 1: Fundamental Algorithms, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1975. Backtracking strategies for constraint problems.

- Sosic, R.; Gu, J. Efficient Local Search with Conflict Minimization: A Case Study of the N-Queens Problem. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 1994, 6, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P. Latin Hypercubes. Discrete Mathematics 2007, 307, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Vigeland, M. Multidimensional Chessboards. Advances in Applied Mathematics 2011, 47, 623–639. [Google Scholar]

- Egge, E.S. A Generalization of the N-Queens Problem. Discrete Mathematics 2005, 301, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.; Stevens, B. A Survey of Known Results and Research Areas for N-Queens. Discrete Mathematics 2009, 309, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, J. Toroidal N-Queens Problem. Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A 2004, 106, 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pólya, G. Über die Anzahl der n-fachen Wiederholungen bei der Gruppenoperationen. Monatshefte für Mathematik 1918, 28, 108–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi, M.Y. On the Complexity of Bounded-Variable Queries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGACT-SIGMOD-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS).; 1995; pp. 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.; Little, J.; O’Shea, D. Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms; Springer: New York, NY, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmfels, B. Solving Systems of Polynomial Equations; American Mathematical Society, 2002.

- Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, M. Topology of Robot Motion Planning. Moscow Mathematical Journal 2004, 4, 527–542. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, G.L.; Mummert, C. Finite Fields and Applications; Vol. 41, Student Mathematical Library, American Mathematical Society, 2007. Orthomorphisms for combinatorial designs.

- McKay, B.D. Isomorph-Free Exhaustive Generation. Journal of Algorithms 2006, 60, 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.; et al. Ergodic Theory in Combinatorial Systems. Probability and Computing 2010, 19, 411–427. [Google Scholar]

- Liskov, M. Cryptographic Applications of N-Queens. Journal of Cryptology 2010, 23, 401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwasser, S.; et al. Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Combinatorial Problems. Advances in Cryptology, 2018; 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Koblitz, N. Elliptic Curve Cryptosystems. Mathematics of Computation 1987, 48, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.H.; Sloane, N.J.A. Sphere Packings, Lattices and Groups; Springer, 1999.

- Alon, N.; Spencer, J.H. The Probabilistic Method, 3rd ed.; Wiley, 2008.

- Bollobás, B. Random Graphs; Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Berge, C. Hypergraphs: Combinatorics of Finite Sets; North-Holland, 1989.

- Diestel, R. Graph Theory; Springer, 2010.

- Farhi, E.; et al. Quantum Computation by Adiabatic Evolution. arXiv:quant-ph/0001106, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.; Chuang, I. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Larcher, G. Discrepancy Estimates for Sequences: New Results and Open Problems. Journal of Complexity 1998, 14, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.P. Enumerative Combinatorics; Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Lovász, L. On the Shannon Capacity of a Graph. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1979, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milnor, J. Morse Theory; Annals of Mathematics Studies, Princeton University Press, 1978.

- Edelsbrunner, H. Computational Topology; American Mathematical Society, 2010.

- Fulton, W. Introduction to Toric Varieties; Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Roth, R. Combinatorial Configurations. Journal of Combinatorial Theory 1981, 30, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg, E. Geometric Approaches to N-Queens. Discrete Mathematics 1980, 32, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kløve, T. Coding Theory and N-Queens. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1981, 27, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chasan, R. Modern Variants of N-Queens. Combinatorial Optimization 2013, 15, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kløve, T. Advanced N-Queens Configurations. Discrete Applied Mathematics 2010, 158, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, I. Codes and Combinatorial Structures. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 1979, 36, 300–310. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).