1. Introduction

SPINK1 (serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 1; OMIM #167790) encodes the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor, synthesized as a 79-amino-acid precursor and processed into a 56-amino-acid mature protein. It is primarily produced by pancreatic acinar cells and has long been proposed to protect the pancreas by inhibiting prematurely activated trypsin (for a recent review, see Wang et al. [

1]). The association of loss-of-function (LoF)

SPINK1 variants with chronic pancreatitis (CP) [

2] provides strong evidence for this protective role, further supported by mouse studies in which

SPINK1 overexpression reduced pancreatitis severity [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Along with gain-of-function variants in

PRSS1 (encoding cationic trypsinogen; OMIM #276000) [

7,

8] and LoF variants in

CTRC (encoding chymotrypsin C, which degrades trypsin [

9]; OMIM #601405) [

10,

11], these findings have established the trypsin-dependent pathway as a central mechanism in CP pathogenesis [

12,

13].

The LoF nature of

SPINK1 variants in CP has enabled the identification of a wide range of variants that are either presumed or experimentally confirmed to cause complete functional loss of the affected allele [

14,

15]. While heterozygous LoF

SPINK1 variants are well recognized to predispose to or cause CP, biallelic variants resulting in complete LoF can lead to a distinct and severe clinical phenotype: severe infantile isolated exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (SIIEPI) [

16]. This condition is characterized by profound exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in early infancy and diffuse pancreatic lipomatosis, without apparent extra-pancreatic involvement. To date, only two individuals with complete

SPINK1 deficiency have been reported—one homozygous for a whole-gene deletion and the other for an Alu insertion in the 3′-untranslated region [

16]. While the former clearly results in a null genotype, the latter causes complete LoF by forming extended double-stranded RNA structures with pre-existing Alu elements in deep intronic regions, thereby silencing

SPINK1 expression [

17]. Consistent with these human findings,

Spink1-deficient mice exhibit widespread pancreatic acinar cell necrosis, leading to perinatal death [

18,

19].

Here, we report compound heterozygosity for complete LoF SPINK1 variants—consisting of a known 2-bp frameshift deletion on one allele and a previously unreported complex rearrangement on the other—as an additional genetic mechanism underlying SPINK1 deficiency in humans. This case expands the mutational spectrum of SIIEPI and highlights the likelihood that this distinct pediatric disorder remains underrecognized in clinical settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Brest University Hospital (Approval No. 3.347-A). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, including the proband—who presented with a phenotype consistent with SIIEPI (see Results)—and both of his parents.

2.2. Reference Sequences, Variant Nomenclature, and Novel Variant Deposition

As in our previous studies [

17,

20], we used the four-exon, pancreas-expressed NM_001379610.1 as the reference

SPINK1 mRNA sequence and NG_008356.2 as the reference

SPINK1 genomic sequence. The novel

SPINK1 variant reported in this study was named in principle according to the guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS;

https://hgvs-nomenclature.org/stable/) [

21], and has been deposited in GenBank (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under accession number PV784948.

2.3. Variant Detection

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on the proband to analyze the entire coding region and exon–intron boundaries of the SPINK1 gene. PCR amplification was carried out using a 48.48 Fluidigm Access Array (Fluidigm, Les Ulis, France) in combination with the FastStart™ High Fidelity PCR System Kit (Sigma Aldrich Chimie S.a.r.l., Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). The targeted DNA sequencing library was prepared following Illumina’s standard protocol and sequenced on the MiniSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Primer sequences and NGS conditions are available upon request from the first author (E.M.). NGS data were analyzed using the SEQNext application (JSI medical systems, Germany).

Notably, copy number variant (CNV) analysis was also performed using the SeqNext application, based on normalized amplicon coverage. For each individual, the read depth of each target amplicon was first normalized against two internal control amplicons. The same normalization was applied to two wild-type (WT) control DNA samples. For each target amplicon, the normalized average coverage from the WT controls was calculated and used as the reference for computing the relative coverage in the study individual. Any amplicon with relative coverage below 75% or above 125% of the control average was classified as a deletion or duplication, respectively.

To confirm the presence of the known SPINK1 variant NM_001379610.1:c.180_181delAT identified by targeted NGS, Sanger sequencing was performed. PCR amplification was performed using the HotStarTaq Master Mix kit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the primer pair: Forward 5’-CAATCACAGTTATTCCCCAGAG-3’ and Reverse 5’-CGGGGTGAGATTCATATTATCAG-3’. After initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, the PCR program consisted of 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation), 60°C for 30 seconds (annealing), and 72°C for 45 seconds (extension). PCR products were purified using the Illustra™ ExoProStar™ (Dominique Dutscher, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France) and sequenced using the BigDye™ Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Illkirch, France) on a 3500 Dx Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were analyzed using the SeqPatient application (JSI medical systems, Germany).

The novel

SPINK1 variant, initially flagged as an exon 2 deletion by targeted NGS, was confirmed by quantitative fluorescent multiplex PCR (QFM-PCR), as previously described [

22]. To define the deletion breakpoint, long-range PCR was performed using the Takara LA Taq with GC Buffer (Takara Bio, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer pair used was: Forward 5’-GCCTTGCTGCCATCTGCCA-3’ (in the promoter) and Reverse 5’-CGGGGTGAGATTCATATTATCAG-3’ (in intron 3). After an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, the PCR program consisted of 14 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds and 60°C for 6 minutes, followed by 16 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds and 62°C for 6 minutes. PCR products were visualized on a 1.0% agarose gel. The patient-specific band was purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and directly sequenced using the BigDye™ Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit with walking primers spaced approximately 500 bp apart. Data were analyzed using the SeqPatient application.

Parental samples were analyzed to determine the inheritance pattern of the two variants.

2.4. Public Databases and Online Tools

3. Results

3.1. The Proband Exhibiting a Phenotype Consistent with SIIEPI

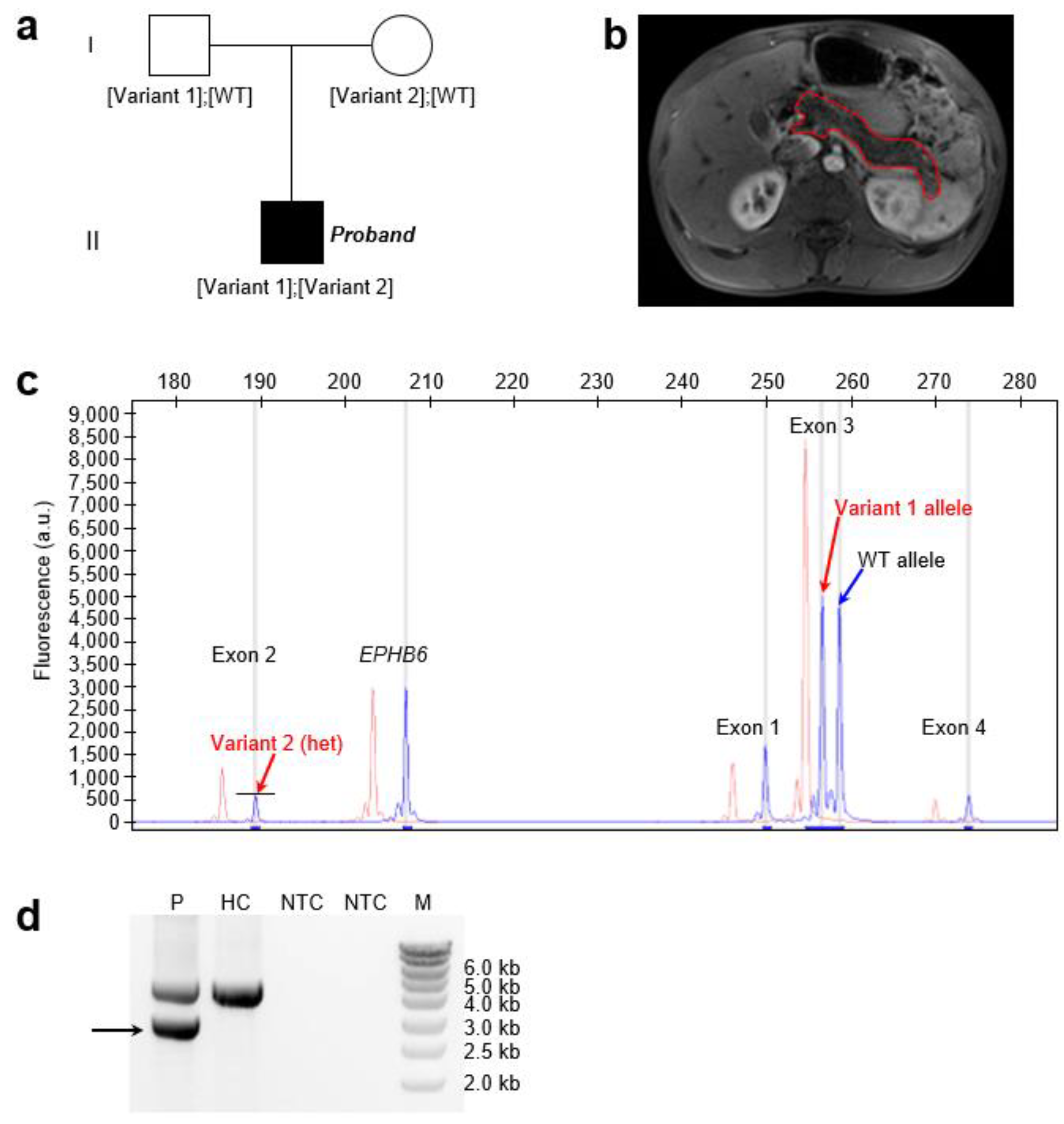

The proband was a 16-year-old boy of Senegalese origin who presented with fatty stools beginning at 10 days of age (

Figure 1a). Between 5 and 11 months of life, his growth slowed, with reduced weight gain. Occasional abdominal pain was reported, but there were no respiratory symptoms. A diagnosis of severe pancreatic exocrine insufficiency was made at 4 years of age, based on clinical steatorrhea. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a pancreas of normal size with diffuse lipomatosis (

Figure 1b). The liver, kidneys, spleen, and gallbladder all showed normal morphology and size. The patient was treated with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, which led to normalization of growth.

Overall, the clinical presentation of the proband closely resembled that of previously reported SIIEPI cases [

16]. No similar cases were identified within the family. It was unknown whether either of the proband’s parents had a history of CP.

3.2. Identification of Compound Heterozyogus Complete LoF SPINK1 Variants in the Proband

In the proband, targeted NGS identified two heterozygous variants in

SPINK1. The first was a heterozygous 2 bp deletion in exon 3: NM_001379610.1:c.180_181delAT (p.(Cys61PhefsTer2)). This variant was detected as two distinct size-separated fluorescent peaks—corresponding to the WT and variant alleles—on QFM-PCR (

Figure 1c), and was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (

Supplementary Figure S1). Parental testing indicated paternal inheritance (

Figure 1a). This variant has previously been reported in the simple heterozygous state in two unrelated individuals with CP [

26]. It is extremely rare in the general population, with an allele frequency of 6.201 × 10⁻⁷ (1/1,612,612) in gnomAD v4.1.0. The variant is predicted to result in complete LoF of the affected allele, as the truncated protein lacks two of the six cysteine residues required to form the three disulfide bonds that stabilize the mature wild-type SPINK1 peptide (see

Figure 2 in Wang et al. [

1]).

Targeted NGS also indicated a heterozygous deletion of

SPINK1 exon 2 in the proband, as evidenced by an approximately 50% reduction in exon 2 coverage compared to two WT controls (

Supplementary Figure S2). This heterozygous deletion was confirmed by QFM-PCR, in which the fluorescent peak corresponding to exon 2 was approximately 50% of that observed in the control sample (

Figure 2c). To identify the deletion breakpoint, we performed long-range PCR using a forward primer located within the

SPINK1 promoter and a reverse primer located within intron 3. Sequencing of the aberrant shorter band (

Figure 1d;

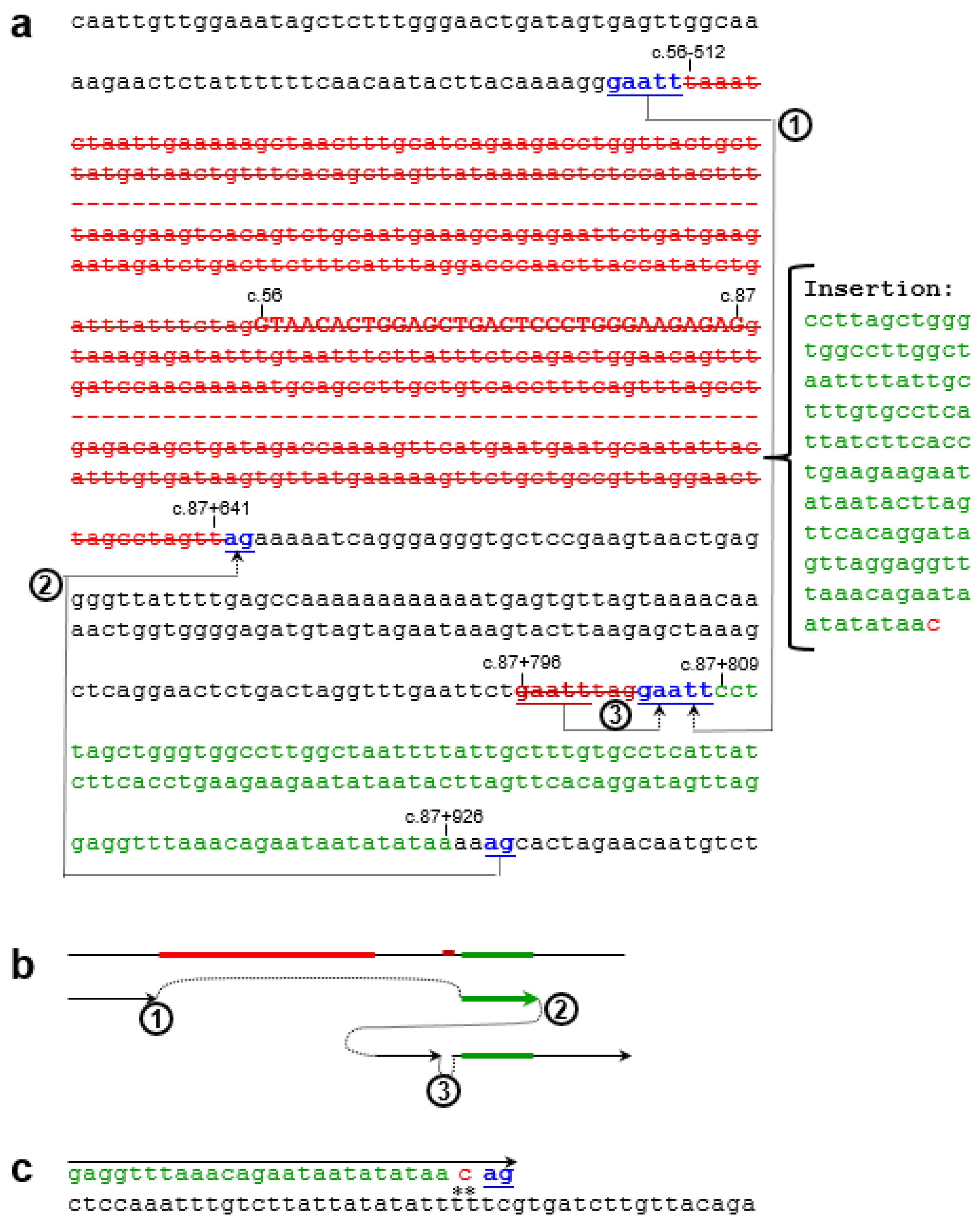

Supplementary Figure S3) revealed a complex rearrangement comprising two components. The first is a 1,185-bp deletion accompanied by a 119 bp insertion, and the second is a simple 8 bp deletion (

Supplementary Figure S4;

Figure 2). Notably, the deleted 1,185-bp genomic segment includes the 32-bp exon 2. The loss of exon 2 from the

SPINK1 coding sequence would unequivocally result in a non-functional protein product. Specifically, this deletion removes coding nucleotides c.56 to c.87, thereby disrupting the reading frame and producing a severely truncated and likely unstable protein lacking essential functional domains. This variant has not been previously reported in the literature and is not registered in ClinVar (as of 16 June 2025). It is also absent from gnomAD SVs v4.1.0.

3.3. Generative Mechanisms and Nomenclature of the Novel Complex Rearrangement Variant

Close examination of the 119-bp insertion revealed that the first 118 bp was templated from c.87+809 to c.87+926, followed by a non-templated cytosine. This, together with the presence of short direct repeats at the deletion/insertion breakpoints (

Figure 2a), suggests that this complex rearrangement can be attributed to replication-based mechanisms [

27], the core of which involves serial replication slippage (SRS) or serial template switching [

28,

29]. Notably, the non-templated cytosine could also be adequately explained by the involvement of translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases in the process [

30]. Key steps of the proposed mechanism are illustrated in

Figure 2b,c. However, analysis using nBMST did not reveal any specific non-B DNA motifs [

25] that might underlie the formation of this novel

SPINK1 variant.

For this novel complex rearrangement variant, the presence of a non-templated single-nucleotide insertion following the 118-bp templated insertion made an exact HGVS-compliant description challenging. We therefore adopted a simplified notation to represent the variant: c.[56-512_87+641delins119bp;87+796_87+803del].

4. Discussion

In this study, we report a novel case whose phenotype closely matches that of the two previously described individuals with SIIEPI. Shared features include early-onset steatorrhea, diffuse pancreatic lipomatosis, and the absence of extra-pancreatic manifestations. Consistent with these clinical observations, we identified a novel

SPINK1 genotype resulting in complete LoF, confirming a biallelic null genotype in this case. This finding reinforces the concept of SIIEPI as a distinct clinical entity caused by complete

SPINK1 deficiency [

16]. It also supports the emerging view that humans with biallelic

SPINK1 LoF—functional “

SPINK1 knockouts”—are viable, and that SPINK1 function is confined largely, if not exclusively, to the exocrine pancreas.

Importantly, the two previously known SIIEPI cases were also reported by our group. Notably, these cases carried either gross deletion or insertion variants—types of variants that are difficult to detect by conventional Sanger sequencing alone. Indeed, all five currently reported CP- or SIIEPI-related gross

SPINK1 structural variants—including the complex rearrangement described in the present case (four deletions and one insertion)—[

16,

22,

31] have been identified by our team using approaches capable of detecting structural variants, such as QFM-PCR followed by long-range PCR. This observation raises the possibility that these gross structural variants, as well as

SPINK1-related SIIEPI, may be underrecognized in clinical settings, especially if only standard sequencing methods are used without complementary CNV analysis or long-range PCR, let alone if only genotyping methods focusing only known pathogenic variants being used.

SPINK1-related SIIEPI also warrants comparison with other genetic forms of early-onset exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, particularly those caused by pathogenic variants in CFTR and CEL. Unlike cystic fibrosis, which typically involves multi-organ dysfunction including chronic pulmonary disease, or CEL-associated MODY8, which often presents with both endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, SIIEPI appears restricted to the exocrine pancreas. Furthermore, it is distinct from syndromic forms of pancreatic insufficiency associated with systemic or developmental abnormalities. The absence of extra-pancreatic features and the consistent identification of biallelic SPINK1 LoF variants across all reported cases strongly support its classification as a non-syndromic, pancreas-specific disorder. These distinctions are clinically important for accurate diagnosis and targeted genetic testing in infants presenting with isolated pancreatic insufficiency.

Beyond its clinical relevance, the novel complex variant described here also offers insights into mutational mechanisms affecting

SPINK1. The rearrangement consists of a 1,185-bp deletion, a 118-bp templated insertion, and an 8-bp microdeletion. The presence of short direct repeats at the breakpoints and the templated nature of the insertion are characteristic of replication-based mechanisms, such as SRS or serial template switching [

27]. Additionally, the presence of a non-templated cytosine at the 3′ end of the insertion suggests the involvement of TLS DNA polymerases [

32], which contribute to complex genomic rearrangements through low-fidelity gap-filling activity [

30].

In conclusion, this study expands the mutational spectrum of SPINK1 associated with complete LoF and provides further evidence that replication-based mechanisms can generate complex pathogenic rearrangements. Our findings also emphasize the clinical relevance of recognizing SIIEPI as a distinct, likely underdiagnosed pediatric disorder caused by biallelic SPINK1 inactivation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Figure S1: Sanger sequencing electropherogram showing the heterozygous 2-bp deletion in

SPINK1 exon 3, NM_001379610.1:c.180_181delAT, in the proband;

Figure S2: Detection of

SPINK1 exon 2 deletion in the proband by targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS);

Figure S3: Uncropped gel image corresponding to

Figure 1d;

Figure S4: Sanger sequencing electropherogram of the novel

SPINK1 complex rearrangement allele.

Author Contributions

Methodology, E.M. and J.M.C.; variant detection, E.M.; clinical investigation and DNA sample collection, M.W. and D.T.; data interpretation, E.M., M.W., D.T., V.R., C.F. and J.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and J.M.C.; writing—review and editing, E.M., M.W., D.T., V.R., C.F. and J.M.C.; funding acquisition, J.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the Association des Pancréatites Chroniques Héréditaires, and the Association Gaétan Saleün, France.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Brest University Hospital (protocol 3.347-A).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are provided within the article and its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT 4o in order to improve readability and language. After using this tool, the authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LoF |

Loss-of-function |

| SIIEPI |

Severe infantile isolated exocrine pancreatic insufficiency |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| QFM-PCR |

Quantitative fluorescent multiplex PCR |

| CP |

Chronic pancreatitis |

| CNV |

Copy number variant |

| WT |

Wild-type |

| HGVS |

The Human Genome Variation Society |

| gnomAD |

The Genome Aggregation Database |

| nBMST |

The non-B DNA Motif Search Tool |

| SRS |

Serial replication slippage |

| TLS |

Translesion synthesis |

References

- Wang, Q.W.; Zou, W.B.; Masson, E.; Férec, C.; Liao, Z.; Chen, J.M. Genetics and clinical implications of SPINK1 in the pancreatitis continuum and pancreatic cancer. Hum Genomics 2025, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, H.; Luck, W.; Hennies, H.C.; Classen, M.; Kage, A.; Lass, U.; Landt, O.; Becker, M. Mutations in the gene encoding the serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romac, J.M.; Ohmuraya, M.; Bittner, C.; Majeed, M.F.; Vigna, S.R.; Que, J.; Fee, B.E.; Wartmann, T.; Yamamura, K.; Liddle, R.A. Transgenic expression of pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor-1 rescues Spink3-deficient mice and restores a normal pancreatic phenotype. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010, 298, G518–G524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, J.D.; Romac, J.; Peng, R.Y.; Peyton, M.; Macdonald, R.J.; Liddle, R.A. Transgenic expression of pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor-i ameliorates secretagogue-induced pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, K.; Araki, K.; Nakano, H.; Nishina, T.; Komazawa-Sakon, S.; Murai, S.; Lee, G.E.; Hashimoto, D.; Suzuki, C.; Uchiyama, Y. , et al. Novel method to rescue a lethal phenotype through integration of target gene onto the X-chromosome. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 37200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Mao, X.T.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.H.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Xiong, S.H.; Liu, M.Y.; Mao, S.H.; Wang, Q.W.; Ma, G.X. , et al. Pancreas-directed AAV8-hSPINK1 gene therapy safely and effectively protects against pancreatitis in mice. Gut 2024, 73, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, D.C.; Gorry, M.C.; Preston, R.A.; Furey, W.; Sossenheimer, M.J.; Ulrich, C.D.; Martin, S.P.; Gates, L.K., Jr.; Amann, S.T.; Toskes, P.P. , et al. Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet 1996, 14, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Maréchal, C.; Masson, E.; Chen, J.M.; Morel, F.; Ruszniewski, P.; Levy, P.; Férec, C. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by triplication of the trypsinogen locus. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 1372–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmola, R.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Chymotrypsin c (caldecrin) promotes degradation of human cationic trypsin: Identity with rinderknecht's enzyme y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 11227–11232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl, J.; Witt, H.; Szmola, R.; Bhatia, E.; Ozsvari, B.; Landt, O.; Schulz, H.U.; Gress, T.M.; Pfutzer, R.; Lohr, M. , et al. Chymotrypsin c (CTRC) variants that diminish activity or secretion are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet 2008, 40, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, E.; Chen, J.M.; Scotet, V.; Le Maréchal, C.; Férec, C. Association of rare chymotrypsinogen c (CTRC) gene variations in patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Hum Genet 2008, 123, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.M.; Férec, C. Chronic pancreatitis: Genetics and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2009, 10, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, E.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Genetic risk in chronic pancreatitis: The trypsin-dependent pathway. Dig Dis Sci 2017, 62, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girodon, E.; Rebours, V.; Chen, J.M.; Pagin, A.; Lévy, P.; Férec, C.; Bienvenu, T. Clinical interpretation of SPINK1 and CTRC variants in pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, E.; Zou, W.B.; Génin, E.; Cooper, D.N.; Le Gac, G.; Fichou, Y.; Pu, N.; Rebours, V.; Férec, C.; Liao, Z. , et al. Expanding ACMG variant classification guidelines into a general framework. Hum Genomics 2022, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venet, T.; Masson, E.; Talbotec, C.; Billiemaz, K.; Touraine, R.; Gay, C.; Destombe, S.; Cooper, D.N.; Patural, H.; Chen, J.M. , et al. Severe infantile isolated exocrine pancreatic insufficiency caused by the complete functional loss of the SPINK1 gene. Hum Mutat 2017, 38, 1660–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, E.; Maestri, S.; Bordeau, V.; Cooper, D.N.; Férec, C.; Chen, J.M. Alu insertion-mediated dsRNA structure formation with pre-existing Alu elements as a disease-causing mechanism. Am J Hum Genet 2024, 111, 2176–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmuraya, M.; Hirota, M.; Araki, M.; Mizushima, N.; Matsui, M.; Mizumoto, T.; Haruna, K.; Kume, S.; Takeya, M.; Ogawa, M. , et al. Autophagic cell death of pancreatic acinar cells in serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 3-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demcsák, A.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Heterozygous Spink1 deficiency promotes trypsin-dependent chronic pancreatitis in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 18, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lin, J.H.; Tang, X.Y.; Marenne, G.; Zou, W.B.; Schutz, S.; Masson, E.; Génin, E.; Fichou, Y.; Le Gac, G. , et al. Combining full-length gene assay and spliceai to interpret the splicing impact of all possible SPINK1 coding variants. Hum Genomics 2024, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.K.; Fokkema, I.; DiStefano, M.; Hastings, R.; Laros, J.F.J.; Taylor, R.; Wagner, A.H.; den Dunnen, J.T. HGVS nomenclature 2024: Improvements to community engagement, usability, and computability. Genome Med 2024, 16, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, E.; Le Marechal, C.; Levy, P.; Chuzhanova, N.; Ruszniewski, P.; Cooper, D.N.; Chen, J.M.; Férec, C. Co-inheritance of a novel deletion of the entire SPINK1 gene with a CFTR missense mutation (l997f) in a family with chronic pancreatitis. Mol Genet Metab 2007, 92, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Francioli, L.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Collins, R.L.; Kanai, M.; Wang, Q.; Alfoldi, J.; Watts, N.A.; Vittal, C.; Gauthier, L.D. , et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 2024, 625, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Chitipiralla, S.; Kaur, K.; Brown, G.; Chen, C.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Jang, W.; Liu, C.; Maddipatla, Z. , et al. Clinvar: Updates to support classifications of both germline and somatic variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D1313–D1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cer, R.Z.; Bruce, K.H.; Mudunuri, U.S.; Yi, M.; Volfovsky, N.; Luke, B.T.; Bacolla, A.; Collins, J.R.; Stephens, R.M. Non-B DB: A database of predicted non-B DNA-forming motifs in mammalian genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D383–D391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, N.; Sarantitis, I.; Rouanet, M.; de Mestier, L.; Halloran, C.; Greenhalf, W.; Férec, C.; Masson, E.; Ruszniewski, P.; Levy, P. , et al. Natural history of SPINK1 germline mutation related-pancreatitis. EBioMedicine 2019, 48, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Cooper, D.N.; Férec, C.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H.; Patrinos, G.P. Genomic rearrangements in inherited disease and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2010, 20, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Chuzhanova, N.; Stenson, P.D.; Férec, C.; Cooper, D.N. Complex gene rearrangements caused by serial replication slippage. Hum Mutat 2005, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Carvalho, C.M.; Lupski, J.R. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell 2007, 131, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Férec, C.; Cooper, D.N. Complex multiple-nucleotide substitution mutations causing human inherited disease reveal novel insights into the action of translesion synthesis DNA polymerases. Hum Mutat 2015, 36, 1034–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, E.; Le Maréchal, C.; Chen, J.M.; Frebourg, T.; Lerebours, E.; Férec, C. Detection of a large genomic deletion in the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet 2006, 14, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.S.; Takata, K.; Wood, R.D. DNA polymerases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).