1. Introduction

The programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is an inhibitory receptor expressed on T cells, which plays a crucial role in maintaining immune homeostasis by limiting excessive immune responses and promoting peripheral tolerance [

1]. Upon binding to its ligand PD-L1 -expressed on both antigen-presenting cells and tumor cells-PD-1 signaling suppresses T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated activation, leading to reduced cytokine production, inhibition of T cell proliferation, and impaired cytotoxic function [

2]. This immune checkpoint mechanism is essential to prevent autoimmunity but is frequently stolen by tumors to evade immune surveillance [

3]. In many cancers, overexpression of PD-L1 facilitates immune escape by dampening antitumor T cell responses.

The blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis with monoclonal antibodies has revolutionized cancer therapy [

4], particularly in melanoma [

5], non-small cell lung carcinoma [

6], and renal cell carcinoma [

7]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 restore T cell effector function and have shown durable responses in a subset of patients [

8]. However, resistance to ICIs and variability in treatment efficacy remain major clinical challenges [

9,

10,

11,

12].

In cancer patients, glucocorticoids (GCs) are administered as part of chemotherapy regimens, for symptom control, and to manage immune-related adverse events during ICI therapy [

13]. Despite their clinical utility, the impact of GCs as antitumor agents remains controversial, due to their potential to interfere with immune checkpoint pathways, tumor cell biology, and the overall antitumor immune response. [

14,

15].

A key molecular mediators of GC activity is Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper (GILZ), a transcriptional target of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [

16,

17]. GILZ and its isoform, long-GILZ (L-GILZ) [

18], exert potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects by modulating NF-κB [

19], MAPK, and AKT signaling pathways [

20]. More recently, GILZ has also been implicated in tumor biology, influencing cell proliferation, apoptosis, and immune evasion [

21,

22,

23,

24]

Emerging evidence suggests a context-dependent relationship between GCs exposure and PD-L1 expression [

15]. In certain cancer, GCs can upregulate PD-L1 via GR-mediated transcriptional mechanisms, contributing to immune suppression and resistance to immunotherapy. Conversely, in other contexts, including specific glioma models, GC treatment may lead to PD-L1 downregulation, potentially restoring antitumor immune responses [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive and prevalent malignant brain tumor in adults, characterized by rapid proliferation, diffuse infiltration, treatment resistance, and a dismal prognosis, with median survival around 15 months despite standard therapies [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The GBM microenvironment is profoundly immunosuppressive, enriched in regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and immunosuppressive cytokines [

33,

34,

35]. Additionally, glioblastoma cells frequently upregulate immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-L1, contributing to immune evasion and posing significant barriers to effective immunotherapy [

36]. Clinical outcomes with ICIs in GBM have thus far been disappointing, likely due to the complex immune microenvironment and frequent use of GCs in this patient population [

37,

38].

Dexamethasone, a potent synthetic GC, is routinely administered to glioblastoma patients to manage tumor-associated cerebral edema [

39,

40]. However, its molecular effects in glioblastoma—particularly regarding PD-L1 regulation—remain poorly understood. Given that GILZ is a known mediator of many GC-induced immunosuppressive effects, it is critical to explore whether GILZ may be involved in modulating PD-L1 expression in glioblastoma.

To address this gap, we investigated the effect of dexamethasone on PD-L1 and GILZ expression in two well-characterized human glioblastoma cell lines, U251 and U87, which are frequently used as comparative models in glioblastoma research due to their distinct molecular and phenotypic profiles [

41,

42,

43]

Our findings reveal that while GCs induce GILZ expression in both glioma lines, PD-L1 downregulation was observed only in U87 cells, suggesting a differential regulatory mechanism that may be relevant for optimizing immunotherapeutic strategies in glioblastoma.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures and Treatments

Human tumor glioblastoma lines U251 and U87 were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) or RPMI-1640 (Euroclone), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) [

41]. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂ [

41]. For experiments, cells were seeded at appropriate densities and treated with dexamethasone (DEX; Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations of 10⁻⁶ M, 10⁻⁷ M, or 10⁻⁸ M for 24 or 48 hours. Untreated cells served as controls.

Western Blot Analysis

Following treatment, cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Total protein concentration was determined, and 30 μg of protein per sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20) and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti–PD-L1 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GILZ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phospho-ERK, anti-ERK (Cell Signaling), and anti-GAPDH (OriGene), used as a loading control. After incubation with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Millipore). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software, with protein levels normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change relative to control.

Flow Cytometry

Cell viability and cell cycle progression were analyzed via flow cytometry to determine the DNA content of cell nuclei stained with PI. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed in phosphate-buffered saline; DNA was stained by incubating the cells in H2O containing 50 μg/mL PI for 30 min at 4 °C. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry using Coulter Epics XL-MCL (Beckman Coulter Inc.) and analyzed by the FlowJo_V10 software.

GILZ Silencing

For GILZ knockdown experiments, U87 cells were transfected with 50 nM small interfering RNA targeting GILZ (siGILZ) or a non-targeting control siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were harvested 48 hours post-transfection for protein extraction and analysis.

GILZ overexpression via TAT-fusion protein

To achieve transient overexpression of GILZ in U87 glioblastoma cells, we employed a recombinant fusion protein composed of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) fused to the GST–TAT carrier (GST–TAT–GILZ). The TAT domain, derived from the HIV-1 transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein, is a well-characterized cell-penetrating peptide that facilitates efficient intracellular delivery of biologically active cargoes, including proteins. The GST moiety enables purification and detection, while the TAT domain ensures cellular uptake without the need for genetic manipulation or transfection reagents. U87 cells were treated with GST–TAT–GILZ at final concentrations of 0.2, 2, or 20 μg/mL for 24 hours under standard culture conditions. Control cells received equivalent concentrations of GST–TAT fusion protein lacking the GILZ domain to account for potential effects of the carrier itself. After treatment, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot to assess GILZ expression levels and downstream targets. This approach enabled functional evaluation of GILZ overexpression under near-physiological conditions, offering a versatile tool for dissecting GILZ-mediated signaling pathways in glioblastoma cells.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism™ software (version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc) was used for all statistical calculations and data visualization.

3. Results

3.1. DEX Induces GILZ Expression but Differentially Regulates PD-L1 DEX and Modulates PD-L1 Expression in Glioblastoma Cell Lines

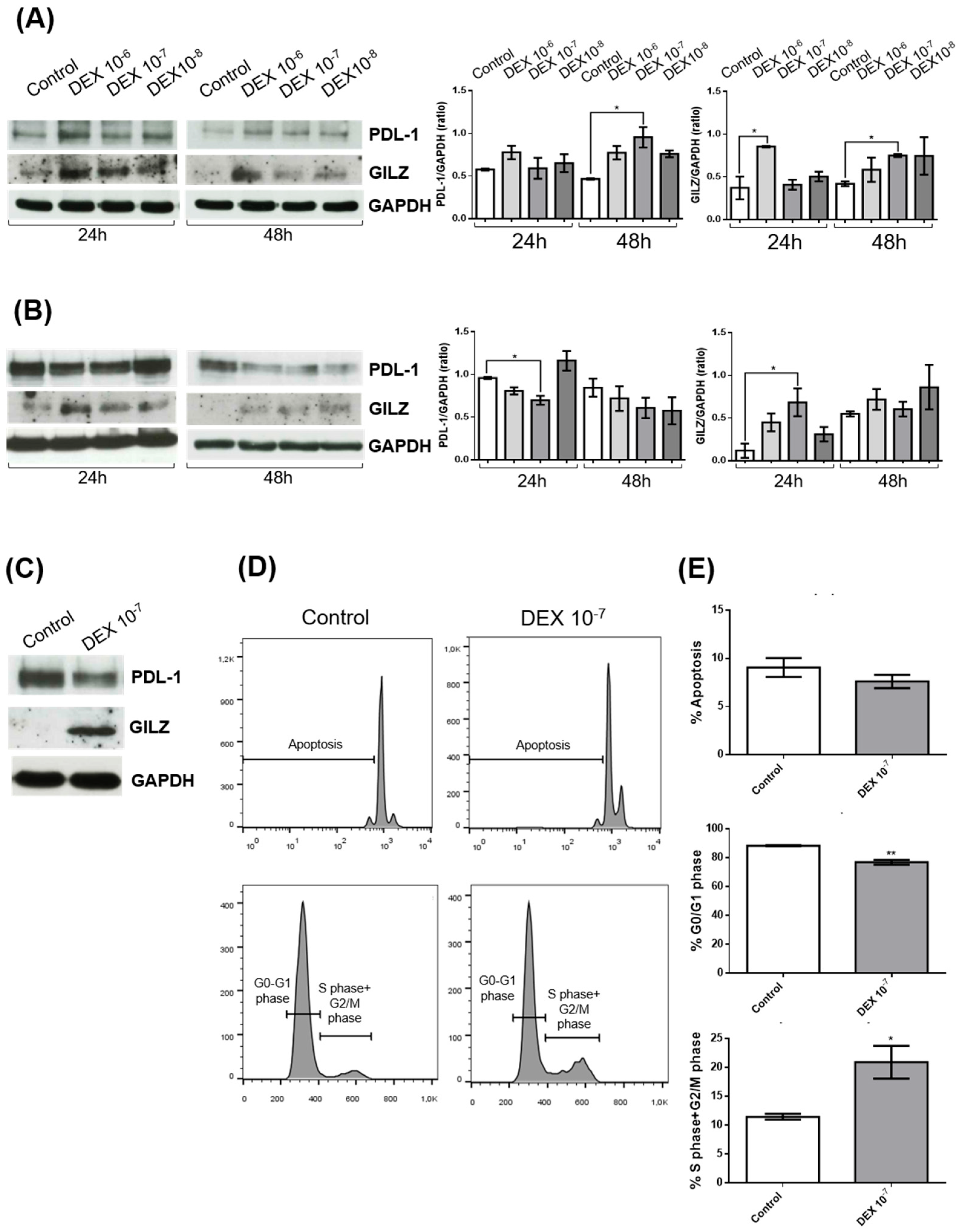

To investigate the effects of dexamethasone (DEX) on PD-L1 and GILZ protein expression in glioblastoma, we treated two human glioblastoma cell lines—U251 and U87—with increasing concentrations of DEX (10⁻⁶ M, 10⁻⁷ M, 10⁻⁸ M) for 24 and 48 hours. Western blot analyses were performed to assess protein levels of PD-L1 and GILZ, with GAPDH used as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of PD-L1 normalized to GAPDH revealed distinct, cell line–specific responses to DEX.

In U251 cells (

Figure 1A), DEX treatment resulted in a dose-dependent increase in GILZ expression at both time points, consistent with activation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) pathway. PD-L1 levels were also significantly increased at 48 hours, particularly at the highest DEX concentration (10⁻⁶ M), indicating a coordinated upregulation of both GILZ and PD-L1 in response to DEX.

Conversely, in U87 cells (

Figure 1B), while GILZ expression was similarly upregulated following DEX treatment, PD-L1 levels were significantly reduced, especially at 24 hours with 10⁻⁶ M DEX. This divergent regulation of PD-L1, despite shared GILZ induction, suggests that DEX influences PD-L1 expression in a cell line–specific manner, potentially due to differences in GR signaling dynamics, transcriptional co-factors, or epigenetic regulation.

To investigate the functional impact of the observed molecular changes, we focused on U87 cells treated with DEX (10⁻⁷ M for 24 h), a condition in which GILZ was upregulated while PD-L1 expression was reduced (

Figure 1C). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that DEX treatment significantly altered cell cycle distribution. U87 cells displayed a reduced proportion in the G0/G1 phase and a corresponding increase in the S and G2/M phases, indicating enhanced cell cycle progression (

Figure 1D,E). No significant differences in apoptosis were detected between treated and control cells.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that DEX consistently induces GILZ expression in glioblastoma cells but exerts heterogeneous effects on PD-L1, enhancing its expression in U251 while suppressing it in U87. Importantly, DEX promotes proliferation in U87 cells, as evidenced by altered cell cycle dynamics, while it does not affect proliferation in U251 cells (data not shown).

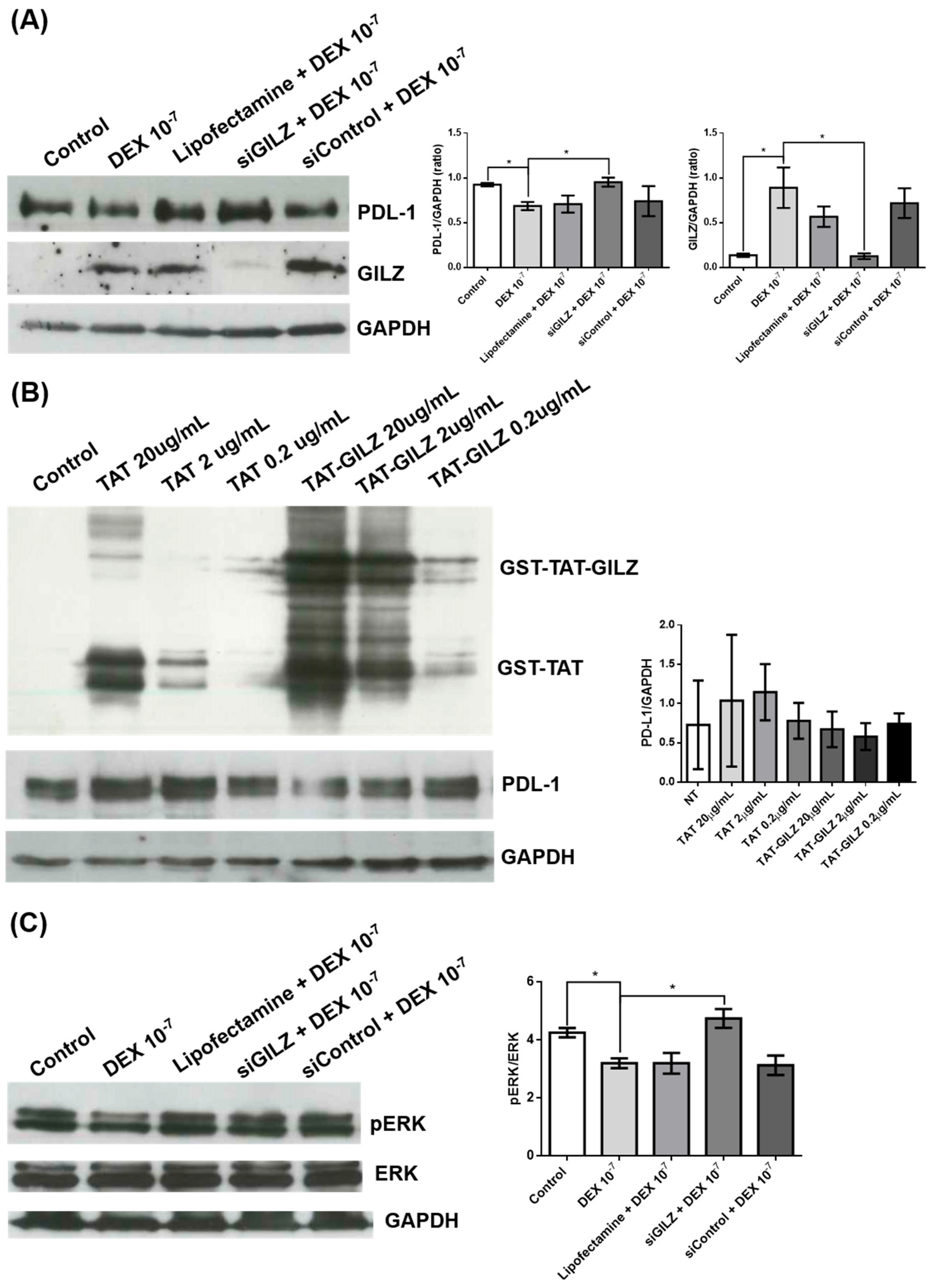

3.2. GILZ Mediates the Downregulation of PD-L1 Expression and Modulates ERK Signaling in U87 Glioblastoma Cells

To further explore the inverse relationship between GILZ and PD-L1 expression suggested by the previous experiments, we performed genetic and pharmacological modulation of GILZ levels in U87 cells. Silencing of GILZ by siRNA (siGILZ) reversed the DEX-induced PD-L1 downregulation. Western blot analysis showed that treatment with DEX (10⁻⁷ M) significantly increased GILZ expression and reduced PD-L1 protein levels. Transfection with siGILZ markedly reduced GILZ expression and restored PD-L1 expression to levels comparable with untreated cells. Control treatments with Lipofectamine and non-targeting control siRNA had no significant effect (

Figure 2A). These data confirm that GILZ is required for the DEX-mediated suppression of PD-L1 in U87 cells.

To further confirm a direct role of GILZ in PD-L1 regulation, we treated U87 cells with a recombinant fusion protein consisting of GST-TAT-GILZ at two concentrations (2 and 0.2 µg/mL). GST-TAT-GILZ was efficiently internalized, as shown by the increased signal in the corresponding western blot (

Figure 2B). PD-L1 expression was progressively reduced with increasing concentrations of GST-TAT-GILZ, while treatment with GST-TAT alone had no effect. These results demonstrate that exogenous (

Figure 2B). GILZ is sufficient to suppress PD-L1 protein levels, reinforcing the role of GILZ as a negative regulator.

Since ERK signaling has been implicated in the regulation of PD-L1, we next investigated whether the GILZ-dependent PD-L1 modulation involved ERK pathway inhibition. Western blot analysis revealed that DEX treatment reduced ERK phosphorylation (pERK/ERK ratio), and this effect was abrogated in siGILZ-transfected cells, indicating that GILZ mediates ERK pathway inhibition (

Figure 2C).

In contrast, neither AKT phosphorylation nor p21 protein levels were affected by DEX treatment or GILZ silencing under the same experimental conditions (data not shown), suggesting a selective involvement of the ERK pathway in this regulatory mechanism. These data suggest that the downregulation of PD-L1 by GILZ may involve, at least in part, suppression of ERK activation.

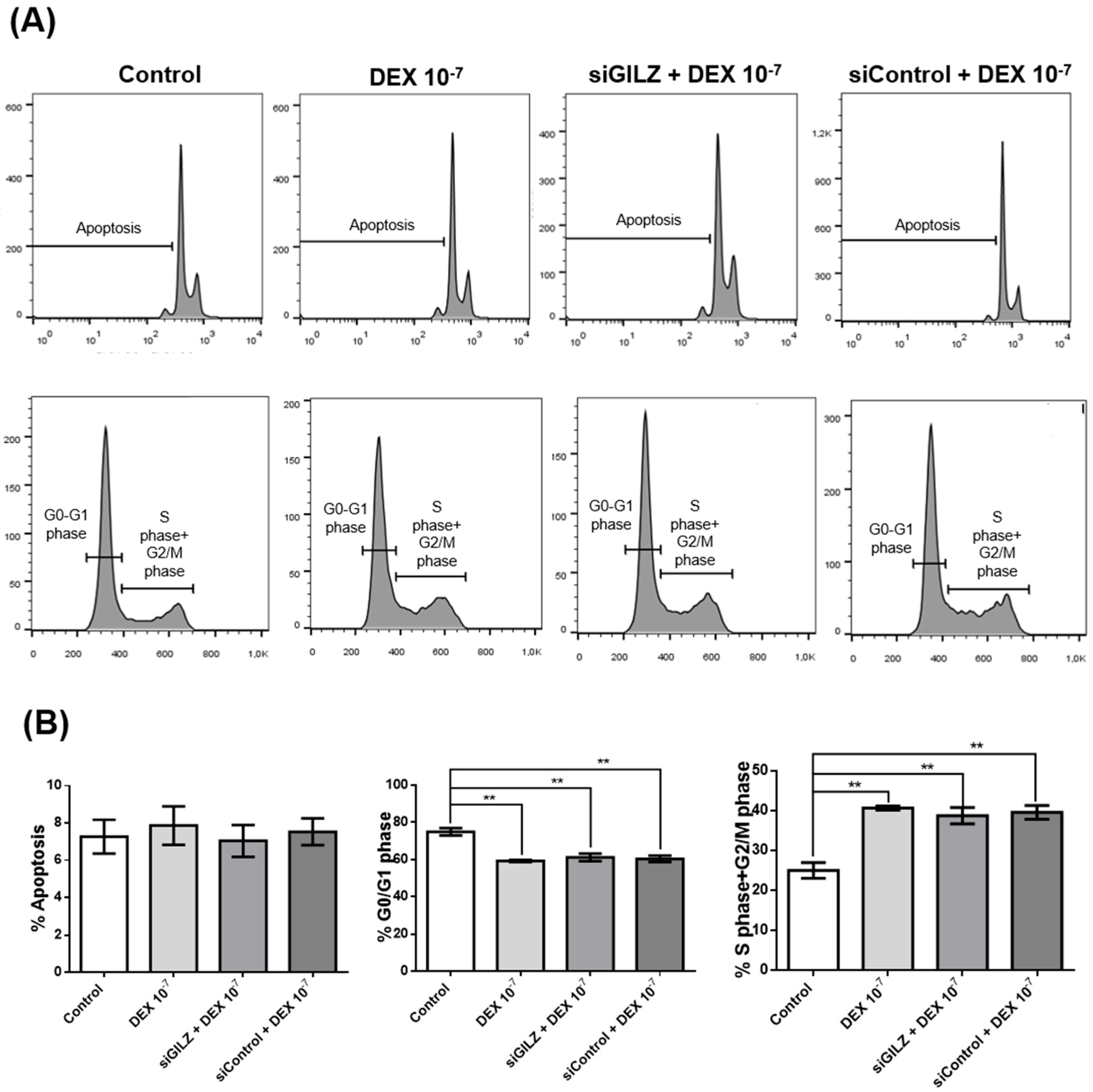

3.3. DEX Promotes Cell Cycle Progression in U87 Cells Independently of GILZ Expression

To determine whether GILZ mediates the proliferative effect of DEX in U87 glioblastoma cells, we performed flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle following GILZ knockdown. Cells were either left untreated, treated with DEX (10⁻⁷ M for 24 h), or transfected with siRNA targeting GILZ. As shown in

Figure 3A and B, DEX treatment significantly reduced the percentage of cells in G0/G1 phase and increased the proportion of cells in S and G2/M phases, consistent with enhanced cell cycle progression. However, silencing of GILZ did not reverse this effect; the cell cycle distribution in siGILZ-transfected cells was comparable to that of DEX-treated cells, with a similar increase in S+G2/M phase fractions (

Figure 3A). Apoptosis rates were unchanged across all conditions (

Figure 3B). These data indicate that the effect of DEX on cell cycle progression in U87 cells occurs independently of GILZ, suggesting that DEX may act through alternative signaling pathways, and that the modulation of PD-L1 and GILZ does not directly drive the proliferative response.

4. Discussion

This study uncovers a novel mechanism by which dexamethasone (DEX), a synthetic glucocorticoid (GC) widely used in oncology, modulates expression of the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1 in glioblastoma cells via induction of the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) protein. Notably, DEX consistently upregulated GILZ in both U87 and U251 glioblastoma cell lines, but its effects on PD-L1 expression diverged—downregulating it in U87 and upregulating it in U251. This suggests that while GR activation and GILZ induction are conserved, PD-L1 regulation is influenced by cell-specific factors such as chromatin accessibility, epigenetic status, or the presence of different transcriptional co-regulators.

Several studies have reported conflicting outcomes regarding the impact of glucocorticoids on PD-L1 expression across tumor types. In models of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma, GCs have been shown to upregulate PD-L1 expression, potentially contributing to immunosuppression and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [

44,

45] .Conversely, other reports—particularly in glioma models—have observed PD-L1 downregulation in response to GR activation [

46]. Our findings support this latter scenario in U87 glioblastoma cells, reinforcing the context-dependent nature of GC action.

GILZ is a well-characterized downstream effector of GR signaling, known for its potent anti-inflammatory functions mediated through inhibition of transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 [

19,

20,

47]. Recent evidence, however, has shown that GILZ can also influence cancer biology, exhibiting either pro- or anti-tumorigenic roles depending on the cellular context [

48,

49,

50]. In glioblastoma, our data suggest that GILZ negatively regulates PD-L1 expression, likely via suppression of the ERK signaling pathway. This is consistent with previous reports that GILZ interacts with Ras/Raf components, leading to suppression of ERK phosphorylation [

20]. In our model, ERK inhibition correlates with PD-L1 downregulation, pointing to a potential mechanism by which GILZ may enhance anti-tumor immune responses.

Importantly, GILZ silencing abrogated both GILZ upregulation and ERK inhibition in DEX-treated U87 cells, supporting a causal role for GILZ in this pathway. However, GILZ silencing did not reverse DEX-induced changes in cell cycle progression—namely, the shift from G0/G1 into S and G2/M phases—suggesting that DEX also exerts GILZ-independent effects on glioblastoma proliferation. These findings reinforce the notion that GILZ selectively modulates immune-related pathways, while other proliferative effects of DEX are likely mediated through separate GR-dependent mechanisms.

This dual effect of DEX—reducing PD-L1 while simultaneously promoting proliferation—raises complex implications for its clinical use. While PD-L1 downregulation may sensitize tumors to immune responses or checkpoint blockade [

6,

36,

45]; enhanced cell cycle progression could promote tumor growth [

51,

52]. These opposing outcomes underscore the importance of dissecting GILZ-dependent and -independent pathways in GR signaling to better understand the net impact of glucocorticoid therapy in glioblastoma.

Interestingly, our findings diverge from those in dendritic cells (DCs), where GILZ silencing reduces PD-L1 expression and boosts their immunostimulatory activity [

53,

54]. In that setting, GILZ supports an immunosuppressive phenotype, indicating a positive role in PD-L1 regulation. This contrast likely reflects the distinct functional roles and signaling environments of immune versus tumor cells. In glioblastoma, GILZ appears to act as a negative regulator of PD-L1, emphasizing the need to evaluate its effects in a cell type–specific manner.

It is important to note that these findings remain preliminary, as the mechanistic data are derived from a single glioblastoma cell line. Future studies using additional glioblastoma models, including patient-derived and in vivo systems, will be crucial to validate the GILZ–PD-L1 regulatory axis and assess its potential relevance for glioblastoma immunotherapy.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that dexamethasone modulates PD-L1 expression in glioblastoma cells in a cell line–specific manner, with a concurrent and consistent induction of GILZ. In U87 cells, GILZ upregulation is associated with a reduction in PD-L1 expression and inhibition of the ERK signaling pathway, suggesting a mechanistic link between GILZ and immune checkpoint regulation. Notably, this effect occurs independently of changes in AKT phosphorylation or p21 expression. These findings contribute to the understanding of glucocorticoid signaling in the glioblastoma microenvironment and highlight the potential of GILZ as a modulator of immunoregulatory pathways in cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.; methodology, S.A. and G.R.; validation, S.A., G.R. and E.A.; formal analysis, S.A. and G.R.; investigation, S.A. and G.R.; data curation, S.A. and G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, E.A. and M.D.; visualization, S.A.; supervision, E.A.; project administration, E.A.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dr. Maria Stefania Antica CERRM EU Grant Agreement KK01.1.1.01.0008, and the Terry Fox Zagreb run and Croatian League Against Cancer.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.5, June 2025) to assist with English language editing, figure legend drafting, and refinement of the Results and Discussion sections. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and revised all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

DEX – Dexamethasone

GR – Glucocorticoid Receptor

PD-L1 – Programmed Death-Ligand 1

GILZ – Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper

siRNA – Small Interfering RNA

siGILZ – GILZ-targeting Small Interfering RNA

siCTRL – Control Small Interfering RNA

ERK – Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase

pERK – Phosphorylated Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase

AKT – Protein Kinase B

pAKT – Phosphorylated AKT

p21 – Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A

GAPDH – Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase

SEM – Standard Error of the Mean

ANOVA – Analysis of Variance

References

- Sharpe, A.H.; Pauken, K.E. The Diverse Functions of the PD1 Inhibitory Pathway. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J. Functions of Immune Checkpoint Molecules Beyond Immune Evasion. In; 2020; pp. 201–226.

- Lin, X.; Kang, K.; Chen, P.; Zeng, Z.; Li, G.; Xiong, W.; Yi, M.; Xiang, B. Regulatory Mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancers. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Assal, A.; Lazar-Molnar, E.; Yao, Y.; Zang, X. Human Cancer Immunotherapy with Antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 Pathway. Trends Mol Med 2015, 21, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Schilling, B.; Liu, D.; Sucker, A.; Livingstone, E.; Jerby-Arnon, L.; Zimmer, L.; Gutzmer, R.; Satzger, I.; Loquai, C.; et al. Integrative Molecular and Clinical Modeling of Clinical Outcomes to PD1 Blockade in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalian, S.L.; Taube, J.M.; Anders, R.A.; Pardoll, D.M. Mechanism-Driven Biomarkers to Guide Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammihal, T.; Saliby, R.M.; Labaki, C.; Soulati, H.; Gallegos, J.; Peris, A.; McCurry, D.; Yu, C.; Shah, V.; Poduval, D.; et al. Immunogenomic Determinants of Exceptional Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nat Cancer 2025, 6, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Robert, C. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. In; 2015; pp. 55–66.

- Lei, Q.; Wang, D.; Sun, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Resistance Mechanisms of Anti-PD1/PDL1 Therapy in Solid Tumors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhen, T.; Cidlowski, J.A. Antiinflammatory Action of Glucocorticoids — New Mechanisms for Old Drugs. New England Journal of Medicine 2005, 353, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.R. Anti-Inflammatory Functions of Glucocorticoid-Induced Genes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2007, 275, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayroldi, E.; Cannarile, L.; Adorisio, S.; Delfino, D. V.; Riccardi, C. Role of Endogenous Glucocorticoids in Cancer in the Elderly. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufall, M.A. Glucocorticoids and Cancer. In; 2015; pp. 315–333.

- Kim, K.N.; LaRiviere, M.; Macduffie, E.; White, C.A.; Jordan-Luft, M.M.; Anderson, E.; Ziegler, M.; Radcliff, J.A.; Jones, J. Use of Glucocorticoids in Patients With Cancer: Potential Benefits, Harms, and Practical Considerations for Clinical Practice. Pract Radiat Oncol 2023, 13, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorisio, S.; Cannarile, L.; Delfino, D. V.; Ayroldi, E. Glucocorticoid and PD-1 Cross-Talk: Does the Immune System Become Confused? Cells 2021, 10, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayroldi, E.; Riccardi, C. Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper (GILZ): A New Important Mediator of Glucocorticoid Action. FASEB Journal 2009, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Adamio, F.; Zollo, O.; Moraca, R.; Ayroldi, E.; Bruscoli, S.; Bartoli, A.; Cannarile, L.; Migliorati, G.; Riccardi, C. A New Dexamethasone-Induced Gene of the Leucine Zipper Family Protects T Lymphocytes from TCR/CD3-Activated Cell Death. Immunity 1997, 7, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscoli, S.; Velardi, E.; Di Sante, M.; Bereshchenko, O.; Venanzi, A.; Coppo, M.; Berno, V.; Mameli, M.G.; Colella, R.; Cavaliere, A.; et al. Long Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper (L-GILZ) Protein Interacts with Ras Protein Pathway and Contributes to Spermatogenesis Control. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayroldi, E.; Migliorati, G.; Bruscoli, S.; Marchetti, C.; Zollo, O.; Cannarile, L.; D’Adamio, F.; Riccardi, C. Modulation of T-Cell Activation by the Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper Factor via Inhibition of Nuclear Factor ΚB. Blood 2001, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayroldi, E.; Zollo, O.; Bastianelli, A.; Marchetti, C.; Agostini, M.; Di Virgilio, R.; Riccardi, C. GILZ Mediates the Antiproliferative Activity of Glucocorticoids by Negative Regulation of Ras Signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2007, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.C.; Cannarile, L.; Ronchetti, S.; Delfino, D. V.; Riccardi, C.; Ayroldi, E. L-GILZ Binds and Inhibits Nuclear Factor ΚB Nuclear Translocation in Undifferentiated Thyroid Cancer Cells. Journal of Chemotherapy 2020, 32, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayroldi, E.; Marchetti, C.; Riccardi, C. The Novel Partnership of L-GILZ and P53: A New Affair in Cancer? Mol Cell Oncol 2015, 2, e975087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugan, K.D.; Ma, C.; Singhal, S.; Krett, N.L.; Rosen, S.T. Dual Regulation of Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper (GILZ) by the Glucocorticoid Receptor and the PI3-Kinase/AKT Pathways in Multiple Myeloma. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 110, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebson, L.; Wang, T.; Jiang, Q.; Whartenby, K.A. Induction of the Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper Gene Limits the Efficacy of Dendritic Cell Vaccines. Cancer Gene Ther 2011, 18, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, R.; Luksik, A.S.; Garzon-Muvdi, T.; Hung, A.L.; Kim, E.S.; Wu, A.; Xia, Y.; Belcaid, Z.; Gorelick, N.; Choi, J.; et al. Contrasting Impact of Corticosteroids on Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy Efficacy for Tumor Histologies Located within or Outside the Central Nervous System. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1500108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, N.; Maruhashi, T.; Sugiura, D.; Shimizu, K.; Okazaki, I.; Okazaki, T. Glucocorticoids Potentiate the Inhibitory Capacity of Programmed Cell Death 1 by Up-Regulating Its Expression on T Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2019, 294, 19896–19906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrini, L.; Vacca, P.; Tumino, N.; Besi, F.; Di Pace, A.L.; Scordamaglia, F.; Martini, S.; Munari, E.; Mingari, M.C.; Ugolini, S.; et al. Glucocorticoids and the Cytokines IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 Present in the Tumor Microenvironment Induce PD-1 Expression on Human Natural Killer Cells. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2021, 147, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, K.; Gu, B.; Zhang, P.; Wu, X. Dexamethasone Enhances Programmed Cell Death 1 (PD-1) Expression during T Cell Activation: An Insight into the Optimum Application of Glucocorticoids in Anti-Cancer Therapy. BMC Immunol 2015, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouyan, A.; Ghorbanlo, M.; Eslami, M.; Jahanshahi, M.; Ziaei, E.; Salami, A.; Mokhtari, K.; Shahpasand, K.; Farahani, N.; Meybodi, T.E.; et al. Glioblastoma Multiforme: Insights into Pathogenesis, Key Signaling Pathways, and Therapeutic Strategies. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Du, A.; Li, J.; Han, H.; Feng, P.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, G.; Yu, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. Transitioning from Molecular Methods to Therapeutic Methods: An In-depth Analysis of Glioblastoma (Review). Oncol Rep 2025, 53, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inggas, M.A.M.; Patel, U.; Wijaya, J.H.; Otinashvili, N.; Menon, V.R.; Iyer, A.K.; Turjman, T.; Dadwal, S.; Gadaevi, M.; Ismayilova, A.; et al. The Role of Temozolomide as Adjuvant Therapy in Glioblastoma Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, F.; Augello, F.R.; Artone, S.; Ayroldi, E.; Giusti, I.; Dolo, V.; Cifone, M.G.; Cinque, B.; Palumbo, P. Cyclooxygenase-2 Upregulated by Temozolomide in Glioblastoma Cells Is Shuttled In Extracellular Vesicles Modifying Recipient Cell Phenotype. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikfalvi, A.; da Costa, C.A.; Avril, T.; Barnier, J.-V.; Bauchet, L.; Brisson, L.; Cartron, P.F.; Castel, H.; Chevet, E.; Chneiweiss, H.; et al. Challenges in Glioblastoma Research: Focus on the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Pang, L.; Dunterman, M.; Lesniak, M.S.; Heimberger, A.B.; Chen, P. Macrophages and Microglia in Glioblastoma: Heterogeneity, Plasticity, and Therapy. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hambardzumyan, D. Immune Microenvironment in Glioblastoma Subtypes. Front Immunol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nduom, E.K.; Wei, J.; Yaghi, N.K.; Huang, N.; Kong, L.-Y.; Gabrusiewicz, K.; Ling, X.; Zhou, S.; Ivan, C.; Chen, J.Q.; et al. PD-L1 Expression and Prognostic Impact in Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2016, 18, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akintola, O.O.; Reardon, D.A. The Current Landscape of Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Glioblastoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2021, 32, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnadurai, M.; McDonald, K.L. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition and Its Relationship with Hypermutation Phenoytype as a Potential Treatment for Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2017, 132, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, D.; Giusti, R.; Mazzotta, M.; Filetti, M.; Krasniqi, E.; Pizzuti, L.; Landi, L.; Tomao, S.; Cappuzzo, F.; Ciliberto, G.; et al. Palliative- and Non-Palliative Indications for Glucocorticoids Use in Course of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibition. Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021, 157, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.; Sabatier, J.-M. Rethinking Corticosteroids Use in Oncology. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.A.; Rodgers, L.T.; Kryscio, R.J.; Hartz, A.M.S.; Bauer, B. Characterization and Comparison of Human Glioblastoma Models. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camphausen, K.; Purow, B.; Sproull, M.; Scott, T.; Ozawa, T.; Deen, D.F.; Tofilon, P.J. Influence of in Vivo Growth on Human Glioma Cell Line Gene Expression: Convergent Profiles under Orthotopic Conditions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 8287–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Liu, Y. Differences in Protein Expression between the U251 and U87 Cell Lines. Turk Neurosurg 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruera, S.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. The Effects of Glucocorticoids and Immunosuppressants on Cancer Outcomes in Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokito, T.; Azuma, K.; Kawahara, A.; Ishii, H.; Yamada, K.; Matsuo, N.; Kinoshita, T.; Mizukami, N.; Ono, H.; Kage, M.; et al. Predictive Relevance of PD-L1 Expression Combined with CD8+ TIL Density in Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Receiving Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2016, 55, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.J.; Gilbert, M.R. Glucocorticoids and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 2021, 151, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayroldi, E.; Riccardi, C. Glucocorticoid-induced Leucine Zipper (GILZ): A New Important Mediator of Glucocorticoid Action. The FASEB Journal 2009, 23, 3649–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayroldi, E.; Cannarile, L.; Delfino, D.V.; Riccardi, C. A Dual Role for Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper in Glucocorticoid Function: Tumor Growth Promotion or Suppression? Review-Article. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redjimi, N.; Gaudin, F.; Touboul, C.; Emilie, D.; Pallardy, M.; Biola-Vidamment, A.; Fernandez, H.; Prévot, S.; Balabanian, K.; Machelon, V. Identification of Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper as a Key Regulator of Tumor Cell Proliferation in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Mol Cancer 2009, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.; Trinh, A.; Balayssac, S.; Maboudou, P.; Dekiouk, S.; Malet-Martino, M.; Quesnel, B.; Idziorek, T.; Kluza, J.; Marchetti, P. Metabolic Rewiring in Cancer Cells Overexpressing the Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper Protein (GILZ): Activation of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation and Sensitization to Oxidative Cell Death Induced by Mitochondrial Targeted Drugs. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2017, 85, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurgali, K.; Rudd, J.A.; Was, H.; Abalo, R. Editorial: Cancer Therapy: The Challenge of Handling a Double-Edged Sword. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayayo-Peralta, I.; Zwart, W.; Prekovic, S. Duality of Glucocorticoid Action in Cancer: Tumor-Suppressor or Oncogene? Endocr Relat Cancer 2021, 28, R157–R171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathelin, D.; Met, Ö.; Svane, I.M. Silencing of the Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper Improves the Immunogenicity of Clinical-Grade Dendritic Cells. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vétillard, M.; Schlecht-Louf, G. Glucocorticoid-Induced Leucine Zipper: Fine-Tuning of Dendritic Cells Function. Front Immunol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).