Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

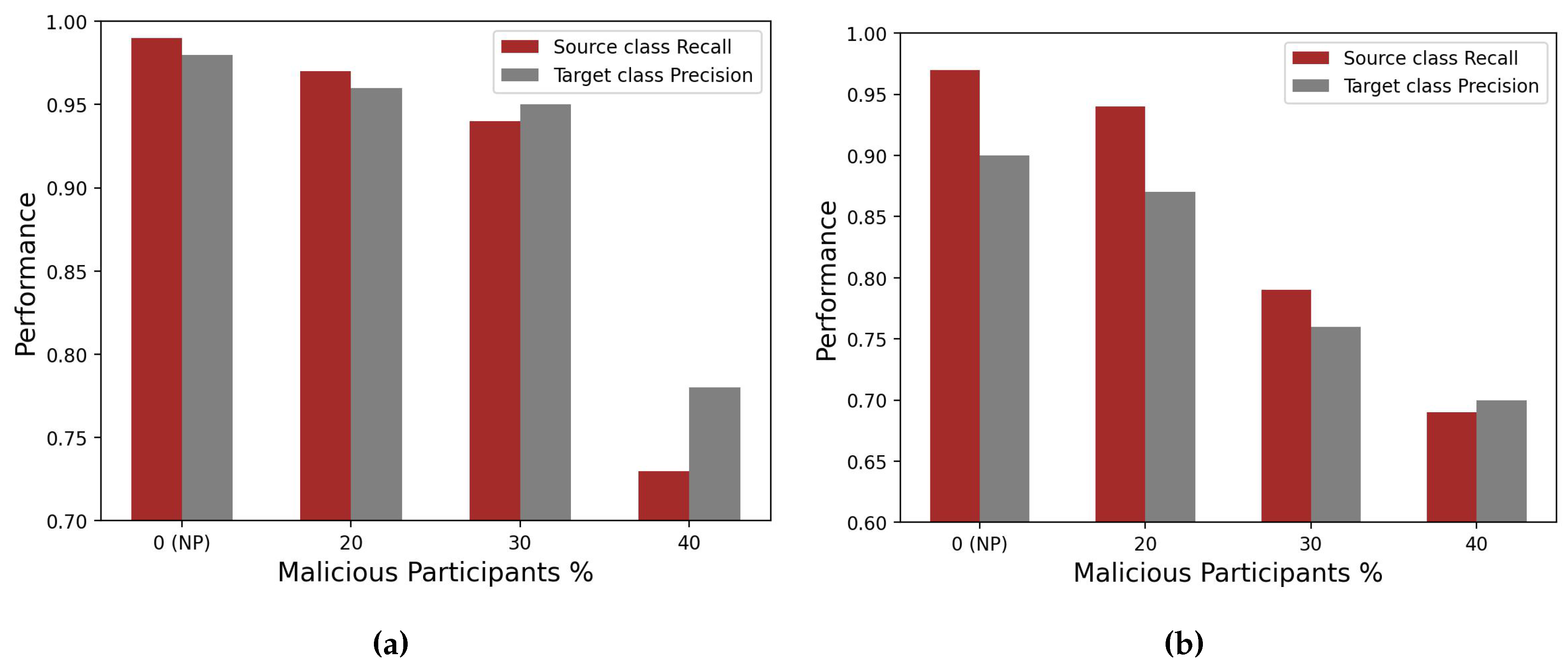

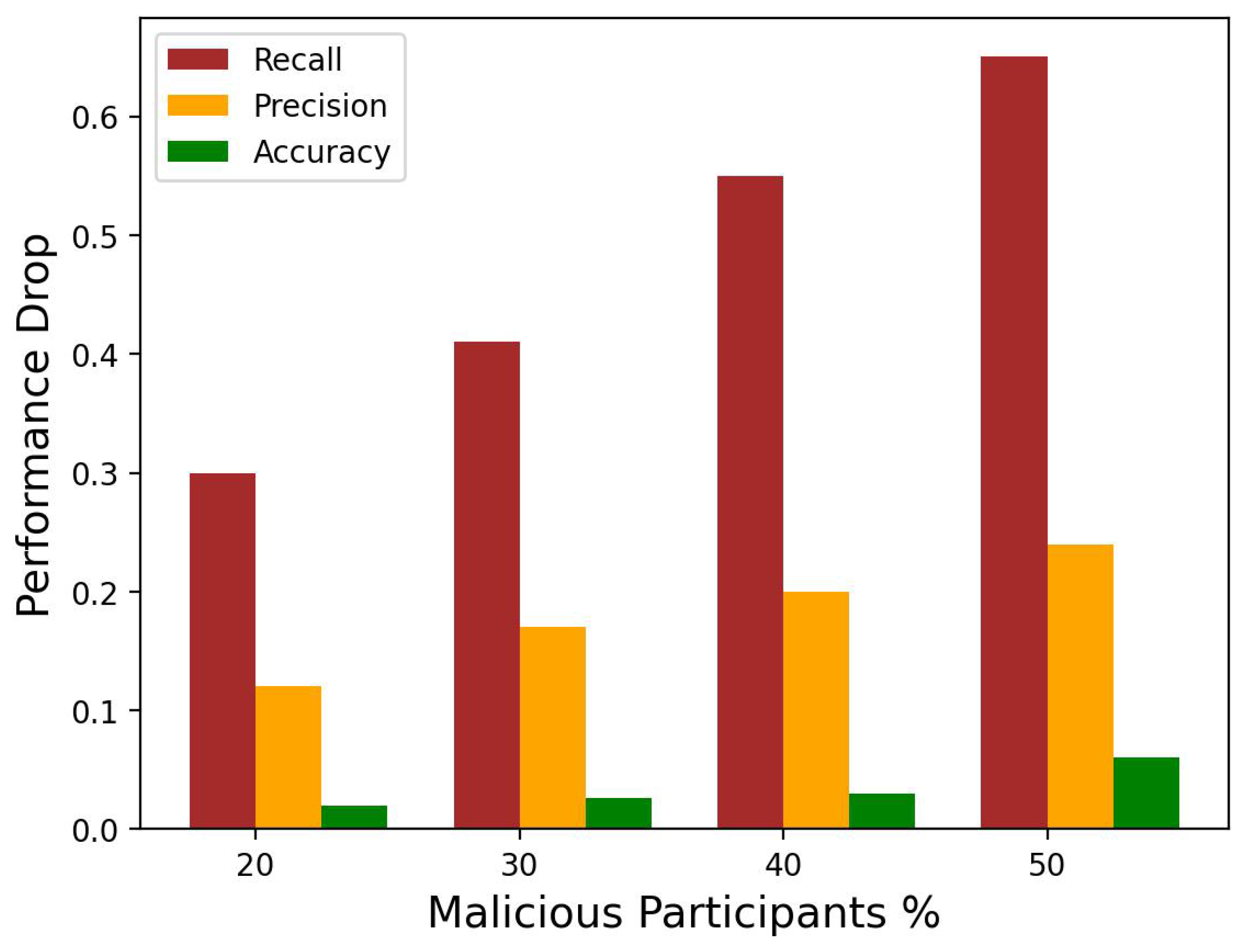

2. Prevention Strategy of Data Poisoning Attacks

- Effect of Compromised workers on Performance: In the federated training setup, we first showed how compromised clients under data poisoning attacks affect the performance of the global model. Experimental results suggested that data poisoning attacks could be targeted, and even a small number of malicious clients cause the global model to misclassify instances belonging to targeted classes while other classes remain relatively intact.

- Proposed Prevention Approach against Data Poisoning Attacks: We propose a confident federated learning (CFL) framework to prevent data poisoning attacks during local training on the worker sides. Along with ensuring data privacy and confidentiality, our proposed approach can successfully detect mislabeled samples, discard them from local training, and ensure prevention against data poisoning attacks.

2.1. Background Literature

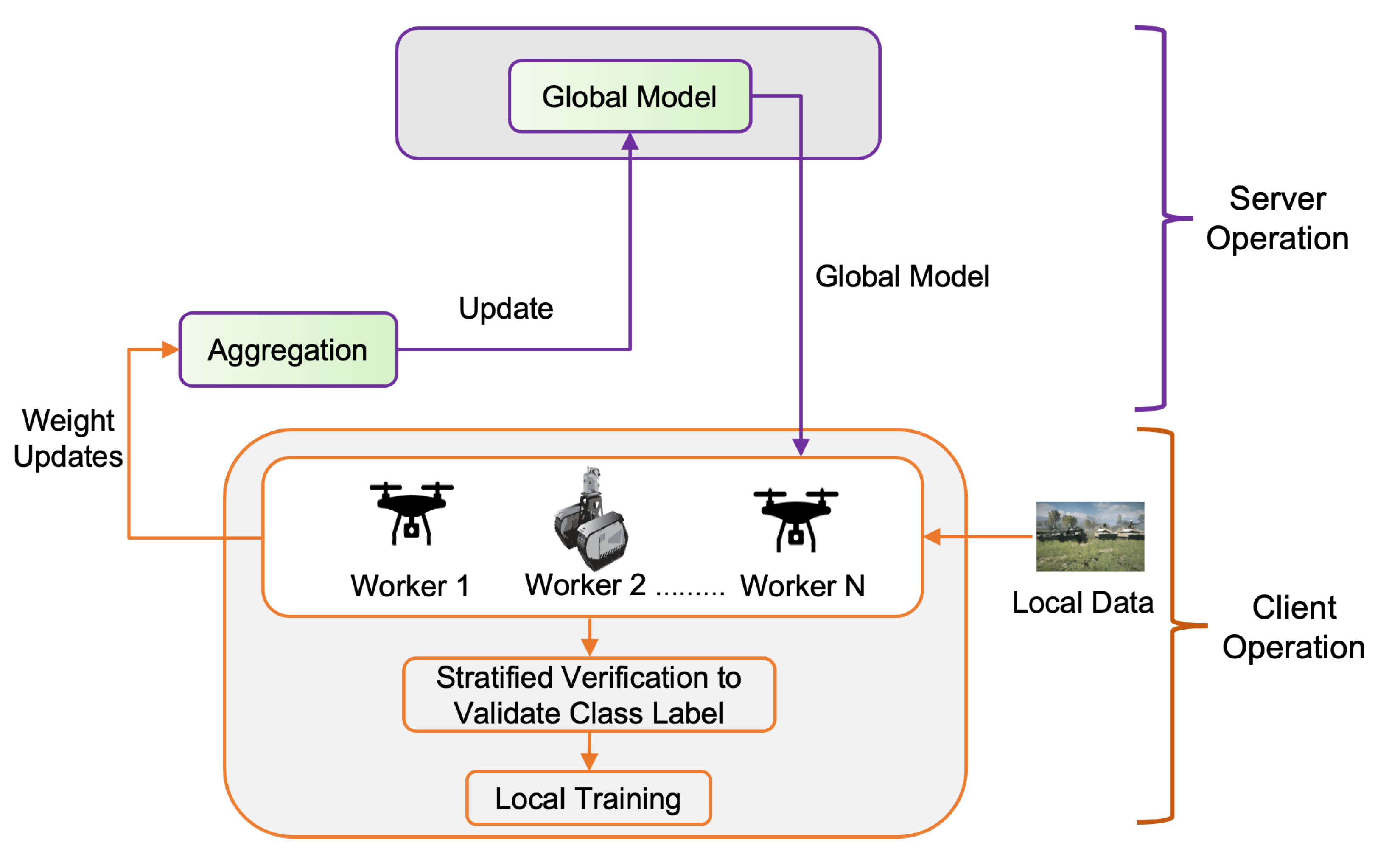

2.2. Methodology: Proposed Prevention Strategy

-

Executed in server

- Weight initialization: The server determines the type of application and how the user will be trained. Based on the application, the global model is built in the server. The server then distributes the global model to selected clients.

-

Aggregation and global update: The server aggregates the local model updates from the participants and then sends the updated global model back to the clients. The server wants to minimize the global loss function [13], i.e.This process is repeated until the global loss function converges or a desirable training accuracy is achieved. The Global Updater function runs on the SGD [37] formula for weight update. The formal equation of global loss minimization formula by the averaging aggregation at the iteration is given below:

-

Executed at the client level

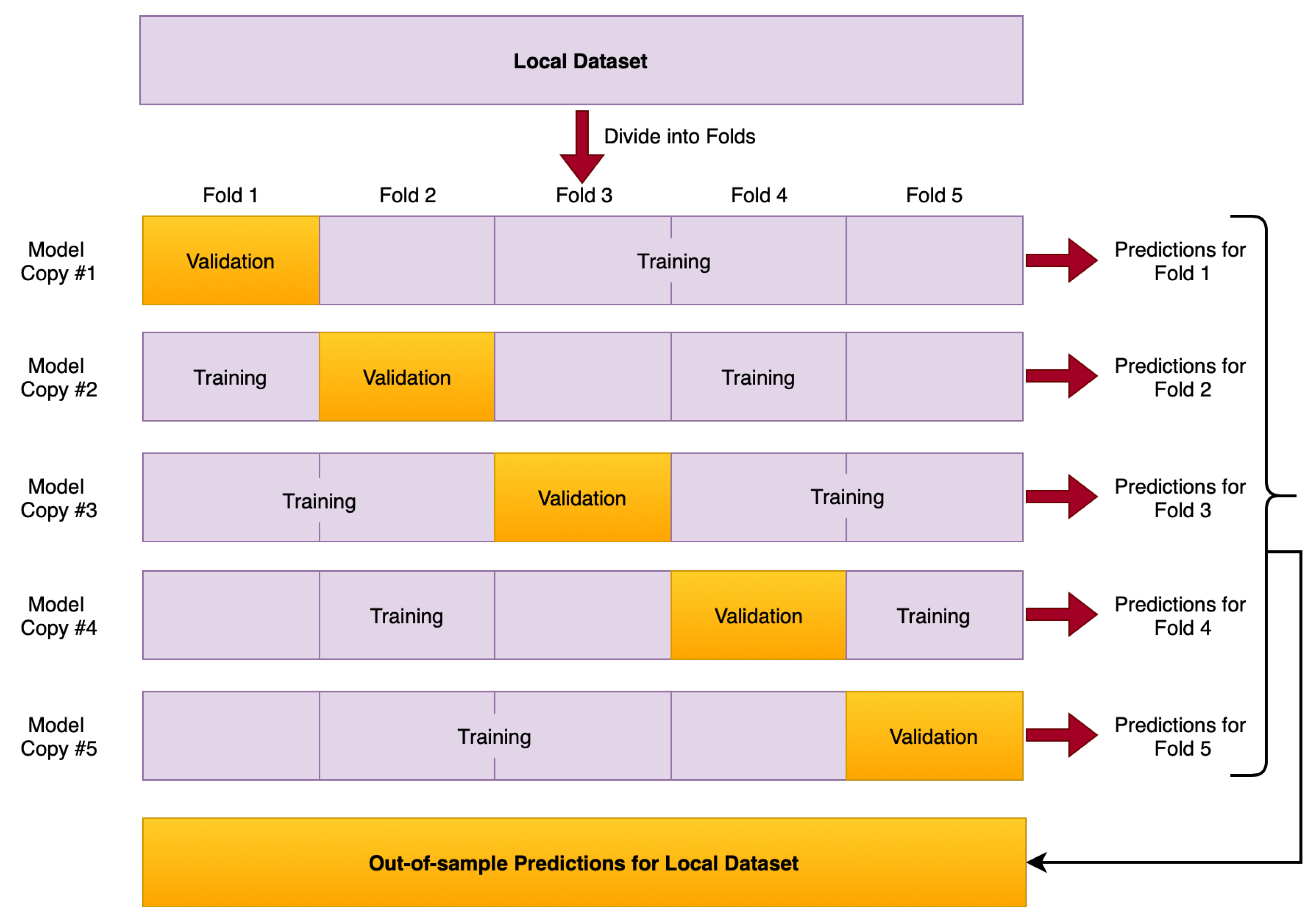

- Validate label quality: Each client will first validate the label quality of local dataset after receiving the global model from the server. To detect the mislabeled samples in local dataset, every participant needs to compute the out-of-sample predictions for every data point of its local dataset. Then out-of-sample prediction and given labels will be utilized to estimate the joint distribution of given and latent true labels, finally estimate the label errors for each pair of true and noisy classes, details in Section 2.3. After validating the class labels of every datapoint in local dataset, overall health score for local dataset can be calculated to track label quality.

- Local training: Each client will utilize from the server, where t stands for each iteration index, start local training on verified local training samples where detected mislabeled samples are discarded from the local training. The client tries to minimize the loss function [13] and searches for optimal parameters .

- Local updates transmission: After each round of training, updated local model weights are sent to the server afterwards. In addition, each client may send the health score of local data so that the server may monitor the label validation process by tracking the health score.

2.3. Stratified Training to Validate Label Quality

2.4. Experiment Setup and Result Analysis

3. Detection Strategy of Data Poisoning Attacks

3.1. Related Literatue

- Representative Dataset based: Approaches within this category exclude or penalize a local update if it has a negative impact on the evaluation metrics of the validation dataset of the global model, e.g. accuracy metrics. Specifically, Studies [38,41] use a validation data set on the server to compute the loss on a designated metric caused by local updates of each worker. Subsequently, updates that detrimentally influence this metric are omitted from the aggregation process of the global model. However, the efficacy of this method hinges on the availability of realistic validation data, which implies a necessity for the server to have insights into the distribution of workers’ data. This requirement poses a fundamental conflict with the principle of Federated Learning (FL), where the server typically may not have the representative dataset alike workers.

- Clustering Based: Methods categorized under this approach involve clustering updates into two groups, with the smaller subset being identified as potentially malicious and consequently excluded from the model’s learning process. Notably, techniques such as Auror [28] and multi-Krum (MKrum) [29] operate under the assumption that data across peers are independent and identically distributed (iid). This assumption, however, leads to increased rates of both false positives and negatives in scenarios where data are not IID [33]. Additionally, these methods necessitate prior knowledge regarding either the characteristics of the training data distribution [28] or an estimation of the anticipated number of attackers within the system [29].

- Model behavior Monitoring Based: Methods under this category operates under the assumption that malicious workers tend to exhibit similar behaviors, which means that their updates will be more similar to each other than to those of honest workers. Consequently, updates are subjected to penalties based on their degree of similarity. For example, FoolsGold (FGold) [27] and CONTRA [33] limit the contribution of potential attackers with similar updates by reducing their learning rates or preventing them from being selected. However, it is worth noting that these approaches can inadvertently penalize valuable updates that exhibit similarities, ultimately resulting in substantial reductions in model performance [42,43].

- Update aggregation: This approach employs resilient update aggregation techniques that are sensitive to outliers at the coordinate level. Such techniques encompass the use of statistical measures like the median [39], the trimmed mean (Tmean) [39], or the repeated median (RMedian) [44]. By adopting these methods, bad updates will have little to no influence on the global model after aggregation. It is worth noting, however, that while these methods yield commendable performance when dealing with updates originating from independent and identically distributed (iid) data, their effectiveness diminishes when handling updates from non-iid data sources. This is primarily due to their tendency to discard a significant portion of information during the model aggregation process. Additionally, the estimation error associated with these techniques grows proportionally to the square root of the model’s size [40]. Furthermore, the utilization of RMedian [44] entails substantial computational overhead due to the regression procedure it performs, while Tmean [39] demands explicit knowledge regarding the fraction of malicious workers within the system.

3.2. Methodology: Proposed Cluster-Based Detection Strategy

3.3. Result Analysis of Proposed Detection Approach

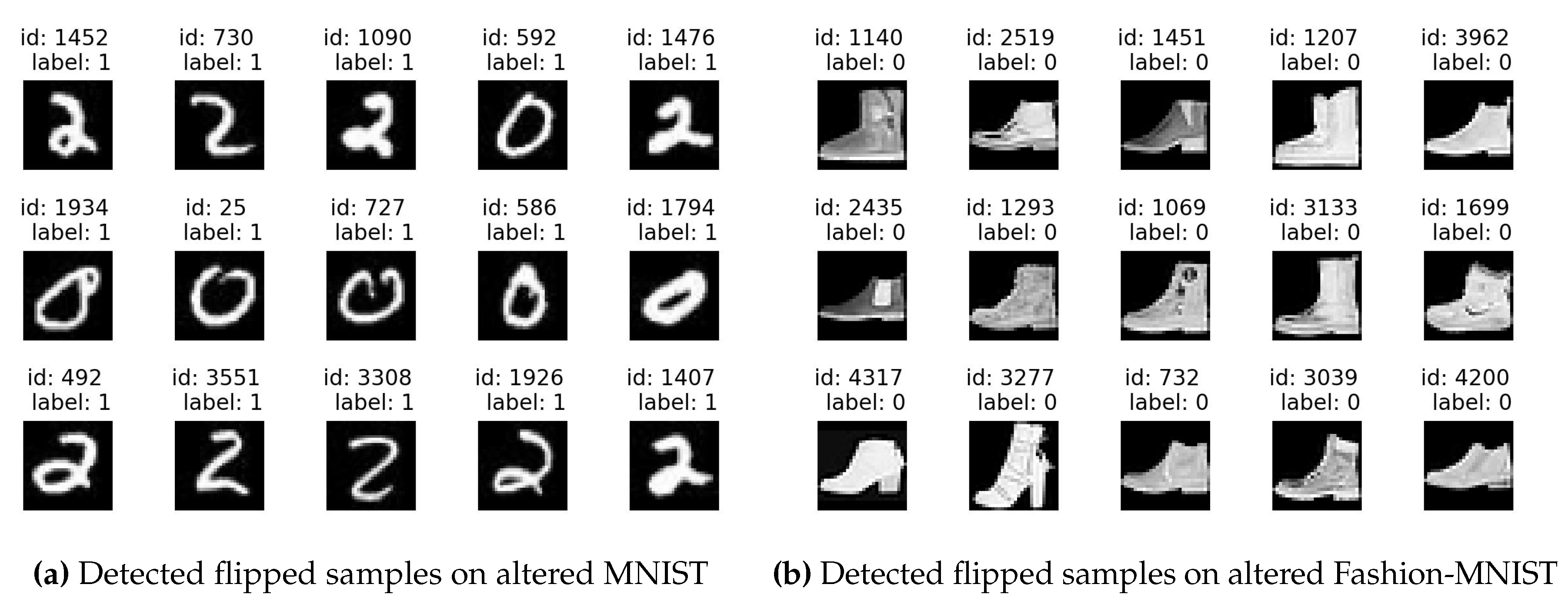

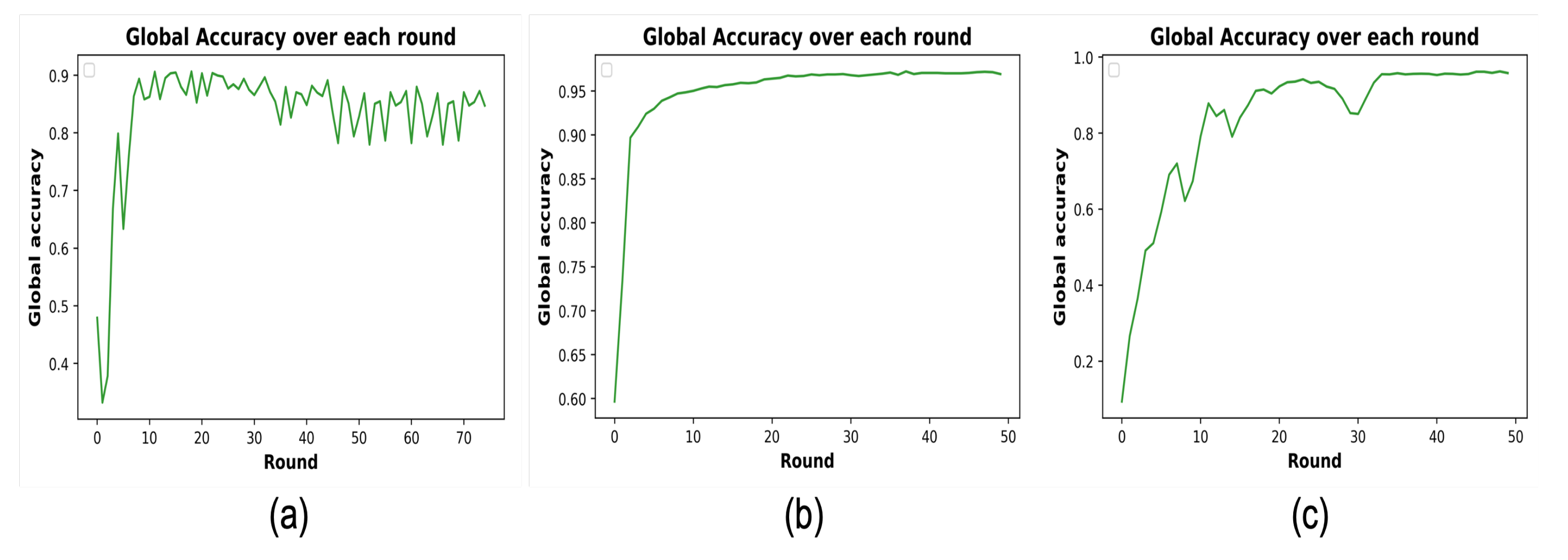

3.4. Effect of Attack on Model’s Convergence

4. Conclusions

References

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Ranzato, M.; Senior, A.; Tucker, P.; Yang, K.; et al. Large scale distributed deep networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, M.; Li, K.; Liao, X.; Li, K. A parallel multiclassification algorithm for big data using an extreme learning machine. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2017, 29, 2337–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Konečnỳ, J.; McMahan, B.; Ramage, D. Federated optimization: Distributed optimization beyond the datacenter. arXiv preprint, 2015; arXiv:1511.03575. [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz, K.; Eichner, H.; Grieskamp, W.; Huba, D.; Ingerman, A.; Ivanov, V.; Kiddon, C.; Konečnỳ, J.; Mazzocchi, S.; McMahan, B.; et al. Towards federated learning at scale: System design. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2019, 1, 374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ovi, P.R.; Dey, E.; Roy, N.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Erbacher, R.F. Towards developing a data security aware federated training framework in multi-modal contested environments. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Multi-Domain Operations Applications IV. SPIE; 2022; Vol. 12113, pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Mathur, A.; Kawsar, F. FLAME: Federated Learning Across Multi-device Environments. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2202.08922. [Google Scholar]

- Tolpegin, V.; Truex, S.; Gursoy, M.E.; Liu, L. Data poisoning attacks against federated learning systems. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer; 2020; pp. 480–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagoji, A.N.; Chakraborty, S.; Mittal, P.; Calo, S. Analyzing federated learning through an adversarial lens. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 634–643. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ling, Q.; Chen, T.; Giannakis, G.B. Federated variance-reduced stochastic gradient descent with robustness to byzantine attacks. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2020, 68, 4583–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Gong, N. Local model poisoning attacks to {Byzantine-Robust} federated learning. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 20); 2020; pp. 1605–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Lu, K.; Song, D. Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning. arXiv preprint, 2017; arXiv:1712.05526. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.Y.B.; Luong, N.C.; Hoang, D.T.; Jiao, Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Yang, Q.; Niyato, D.; Miao, C. Federated learning in mobile edge networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 2031–2063. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.; Xiao, H.; Eckert, C. Adversarial label flips attack on support vector machines. In ECAI 2012; IOS Press, 2012; pp. 870–875.

- Northcutt, C.; Jiang, L.; Chuang, I. Confident learning: Estimating uncertainty in dataset labels. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2021, 70, 1373–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdasaryan, E.; Veit, A.; Hua, Y.; Estrin, D.; Shmatikov, V. How to backdoor federated learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR; 2020; pp. 2938–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Kairouz, P.; Suresh, A.T.; McMahan, H.B. Can you really backdoor federated learning? arXiv preprint, 2019; arXiv:1911.07963. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, L.; Song, C.; De Cristofaro, E.; Shmatikov, V. Exploiting unintended feature leakage in collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE; 2019; pp. 691–706. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ovi, P.R.; Dey, E.; Roy, N.; Gangopadhyay, A. Mixed Precision Quantization to Tackle Gradient Leakage Attacks in Federated Learning. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2210.13457. [Google Scholar]

- Ovi, P.R.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Erbacher, R.F.; Busart, C. Secure Federated Training: Detecting Compromised Nodes and Identifying the Type of Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1115–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Cong, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, Q.; Lyu, L.; Liu, J. Data poisoning attacks on federated machine learning. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 9, 11365–11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive privacy analysis of deep learning: Passive and active white-box inference attacks against centralized and federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE; 2019; pp. 739–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, T.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Garg, S. Badnets: Identifying vulnerabilities in the machine learning model supply chain. arXiv preprint, 2017; arXiv:1708.06733. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, G.; Baruch, M.; Goldberg, Y. A little is enough: Circumventing defenses for distributed learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Biggio, B.; Nelson, B.; Laskov, P. Poisoning attacks against support vector machines. arXiv preprint, 2012; arXiv:1206.6389. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, C.; Yoon, C.J.; Beschastnikh, I. The limitations of federated learning in sybil settings. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions and Defenses (RAID 2020); 2020; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Tople, S.; Saxena, P. Auror: Defending against poisoning attacks in collaborative deep learning systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference on Computer Security Applications, 2016; pp. 508–519.

- Blanchard, P.; El Mhamdi, E.M.; Guerraoui, R.; Stainer, J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, C.; Yoon, C.J.; Beschastnikh, I. Mitigating sybils in federated learning poisoning. arXiv preprint, 2018; arXiv:1808.04866. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Gong, N.Z. FLDetector: Defending federated learning against model poisoning attacks via detecting malicious clients. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2022; pp. 2545–2555.

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Lu, R. Privacy-enhanced federated learning against poisoning adversaries. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 4574–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, S.; Luo, B.; Li, F. Contra: Defending against poisoning attacks in federated learning. In Proceedings of the Computer Security–ESORICS 2021: 26th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Darmstadt, Germany,, October 4–8 2021; Proceedings, Part I 26. Springer, 2021. pp. 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Jebreel, N.M.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Sánchez, D.; Blanco-Justicia, A. Defending against the label-flipping attack in federated learning. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2207.01982. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wong, W.E.; Wang, W.; Yao, Y.; Chau, M. Detection and mitigation of label-flipping attacks in federated learning systems with KPCA and K-means. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications (DSA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Wei, K.; Chen, W.; Poor, H.V. Federated learning with unreliable clients: Performance analysis and mechanism design. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 17308–17319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sharma, V.; Mohanty, S.P. Preserving data privacy via federated learning: Challenges and solutions. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2020, 9, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagielski, M.; Oprea, A.; Biggio, B.; Liu, C.; Nita-Rotaru, C.; Li, B. Manipulating machine learning: Poisoning attacks and countermeasures for regression learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE; 2018; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, D.; Chen, Y.; Kannan, R.; Bartlett, P. Byzantine-robust distributed learning: Towards optimal statistical rates. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2018; pp. 5650–5659. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Shejwalkar, V.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Cronus: Robust and heterogeneous collaborative learning with black-box knowledge transfer. arXiv preprint, 2019; arXiv:1912.11279. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B.; Barreno, M.; Chi, F.J.; Joseph, A.D.; Rubinstein, B.I.; Saini, U.; Sutton, C.; Tygar, J.D.; Xia, K. Exploiting machine learning to subvert your spam filter. LEET 2008, 8, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ngai, E.; Ye, F.; Voigt, T. Auto-weighted robust federated learning with corrupted data sources. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Rieger, P.; De Viti, R.; Chen, H.; Brandenburg, B.B.; Yalame, H.; Möllering, H.; Fereidooni, H.; Marchal, S.; Miettinen, M.; et al. {FLAME}: Taming backdoors in federated learning. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22); 2022; pp. 1415–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, A.F. Robust regression using repeated medians. Biometrika 1982, 69, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).