Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

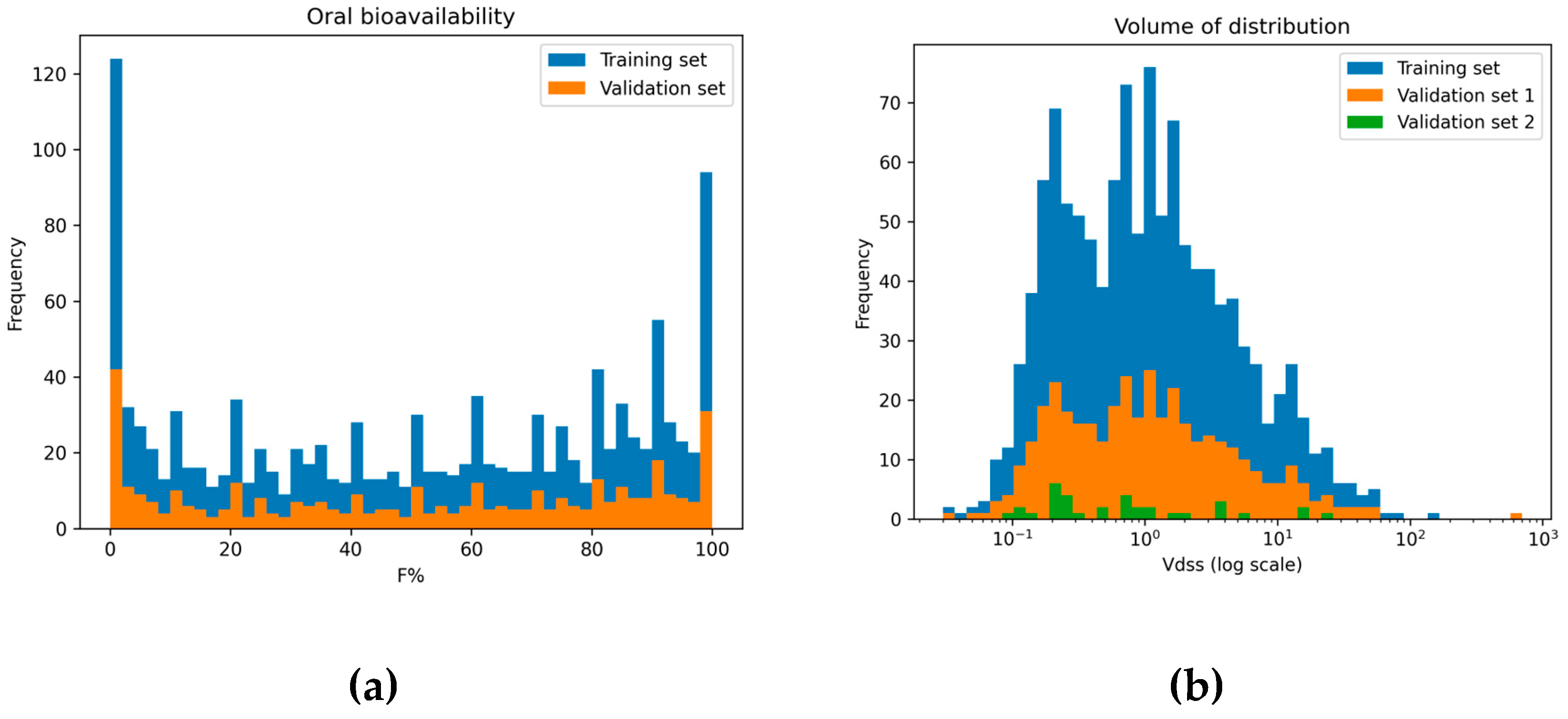

2.1. Data Distribution

2.1.1. Oral Bioavailability

2.1.2. Volume of Distribution

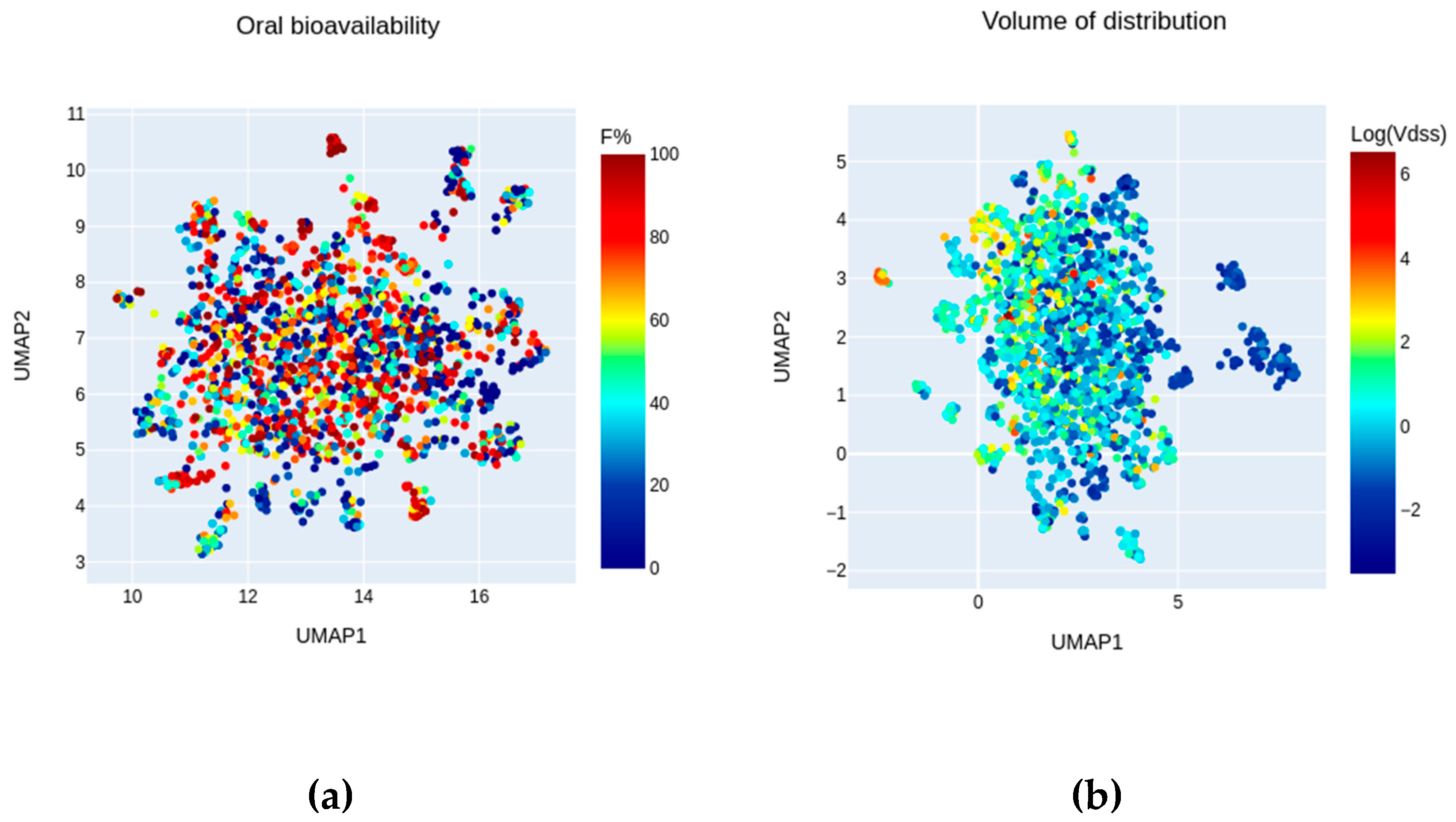

2.2. Chemical Space

2.3. Predictive Performance

2.3.1. Oral Bioavailability

2.3.2. Volume of Distribution

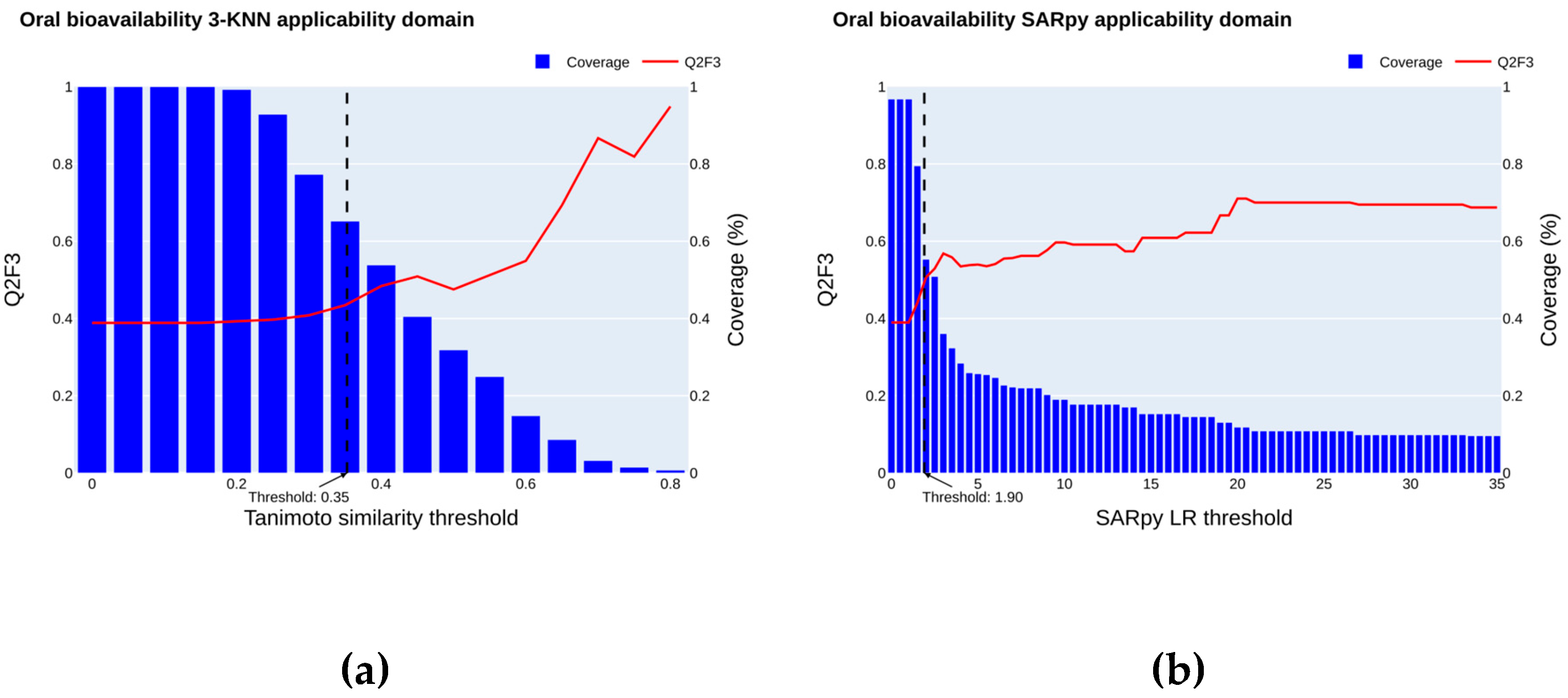

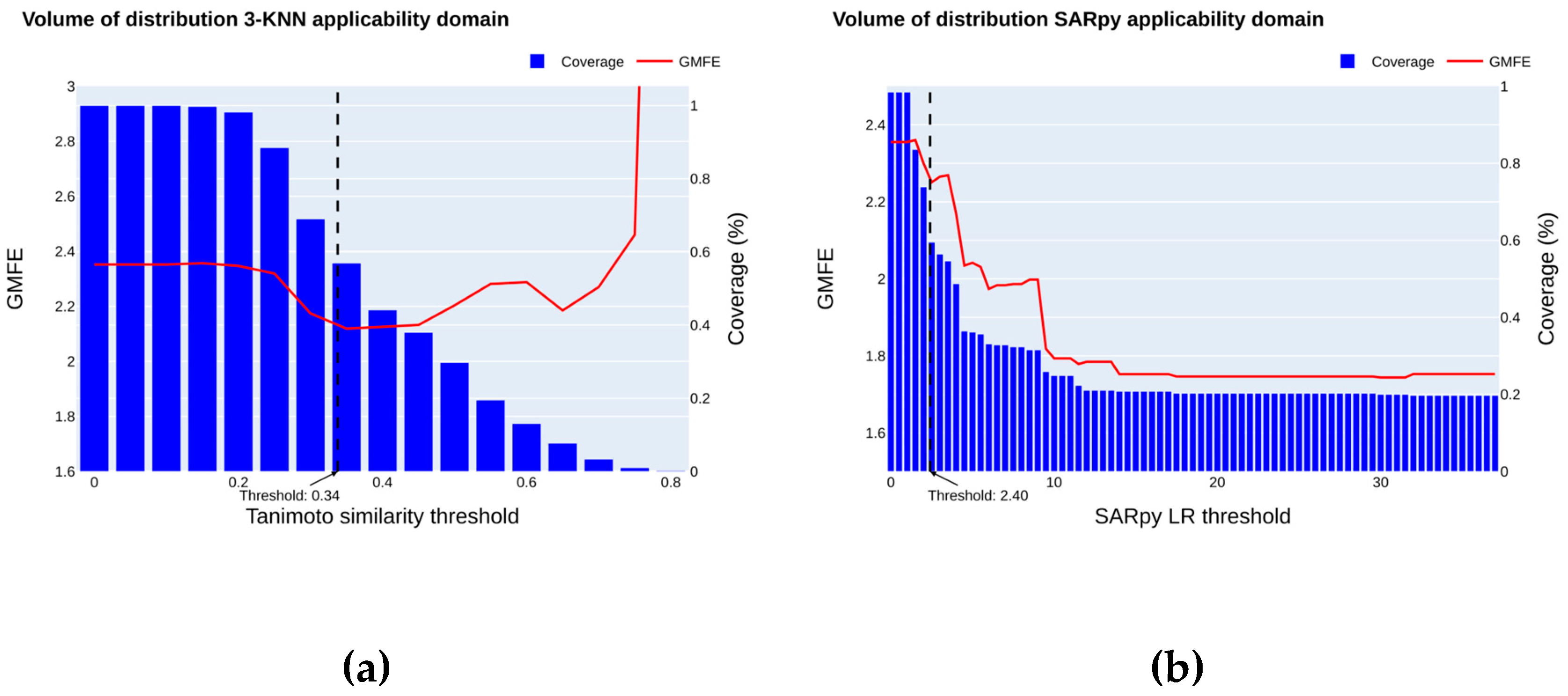

2.4. Applicability Domain

2.4.1. Oral Bioavailability

2.4.2. Volume of Distribution

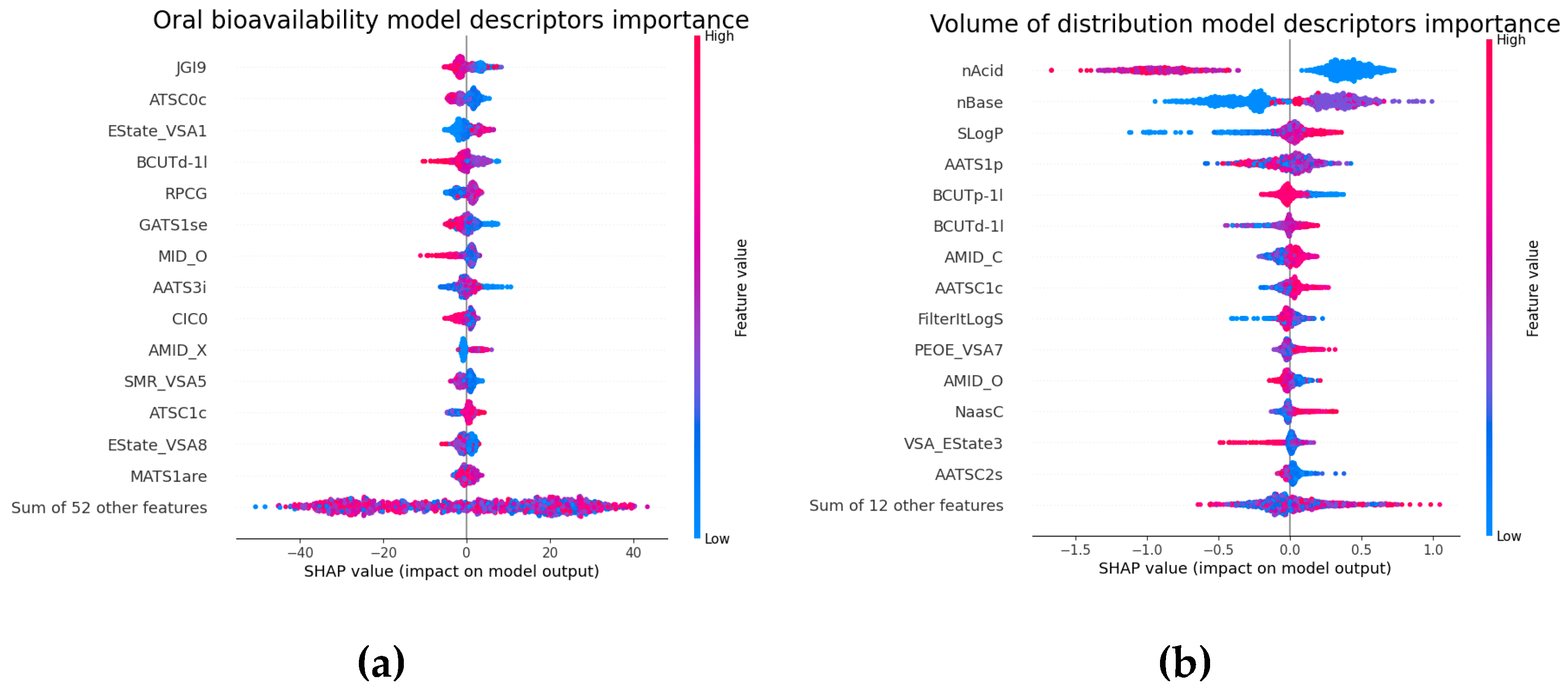

2.5. Molecular Descriptors Importance

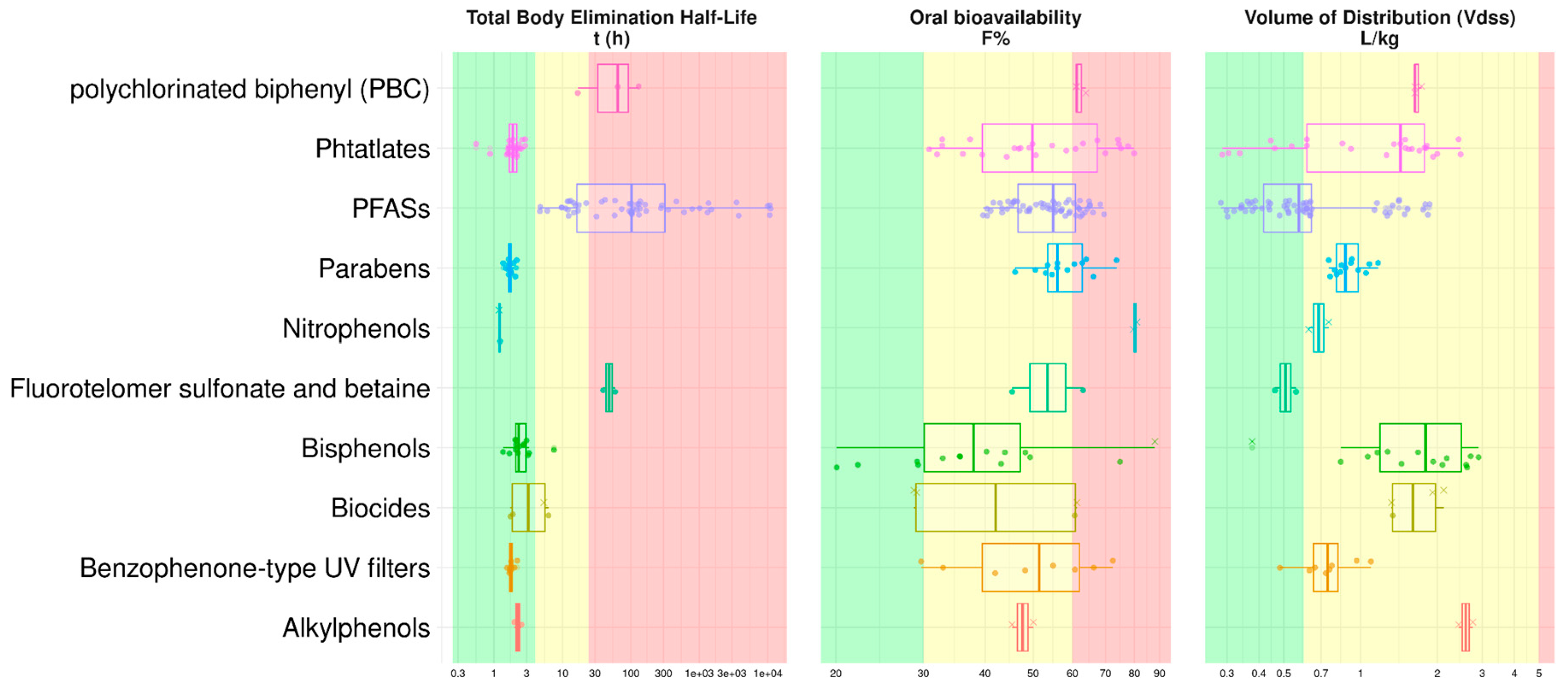

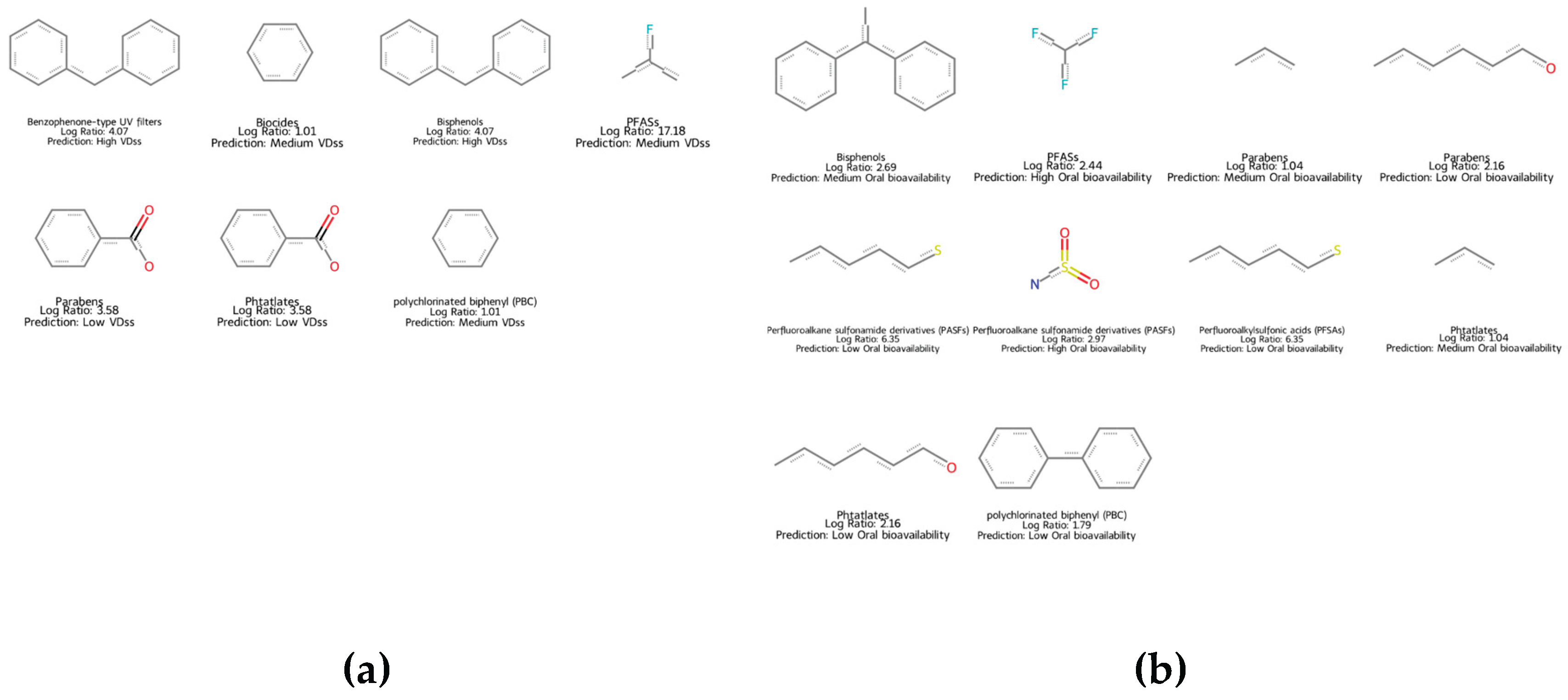

2.6. QSAR Mapping of EDC as a Function of Key TK Properties

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data

4.1.1. Oral Bioavailability

4.1.2. Volume of Distribution

4.1.3. Preprocessing Standardization

4.2.1. Oral Bioavailability

4.2.2. Volume of Distribution

4.3. Molecular Descriptors

4.4. Selection of Molecular Descriptors

- Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that combines the output of multiple decision trees to make a prediction. It can be useful for the development of classification as well as regression models.

- XGBoost and CatBoost are two optimized gradient boosting libraries designed for highly efficient parallel tree boosting, where each successive tree corrects the errors of the previous one.

- CatBoost uses ordered boosting that allows to train a model by performing a permutation on a subset of data while calculating residuals on another subset. The CatBoost library can handle categorical data.

- Chemprop is a python package performing directed message passing neural networks (D-MPNN) designed to treat molecular properties. D-MPNN is a class of graph-convolutional neural networks where chemicals are represented as edges and vertices. The model works in two steps: the message passing phase which transforms the chemical into a neural representation and the readout phase which makes the prediction considering the neural representation of the chemical. The chemprop package allows to compute morgan fingerprints [61] or RDKit [62] 2D fingerprints as additional molecular descriptors to improve the performance of the generated models. We choose to include the RDKit 2d molecular descriptors in our modeling process with an ensemble size of 5 (number of developed models whose predictions are averaged) [63].

- SARpy is a modelling approach implemented in python to facilitate the modeling of structure-activity relationship models. It recursively mines every substructure in a training set. Each substructure is explored as a potential structural alert on the training set by assessing its predictive power. When a specific structural alert is found within a query chemical, the activity associated with the alert is then attributed to this chemical to predict the biological property of interest. The SARpy method is designed only for classification.

4.6. Protocol

4.7. Predictive Performance

4.8. Applicability Domain

4.8.1. K Nearest Neighbors

4.8.2. SARpy

4.9. Mapping of EDC Chemicals

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| R | Regression |

| BC | Binary Classification |

| MC | Multiclass Classification |

| TK | Toxicokinetics |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| GMFE | Geometric Mean Fold Error |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship |

| VD | Volume of distribution |

| VDss | Volume of distribution at steady state |

| EDC | Endocrine disruptors chemicals |

| SE | Sensitivity |

| SP | Specificity |

| BA | Balanced accuracy |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| 3-NN | Three nearest neighbours |

| AD | Applicability Domain |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction |

References

- Shanmugam, P.S.T.; Sampath, T.; Jagadeeswaran, I.; Bhalerao, V.P.; Thamizharasan, S.; V., K.; Saha, J. Toxicokinetics. In Biocompatibility Protocols for Medical Devices and Materials; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 175–186. ISBN 978-0-323-91952-4. [Google Scholar]

- Coecke, S.; Pelkonen, O.; Leite, S.B.; Bernauer, U.; Bessems, J.G.; Bois, F.Y.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Loizou, G.; Testai, E.; Zaldívar, J.-M. Toxicokinetics as a Key to the Integrated Toxicity Risk Assessment Based Primarily on Non-Animal Approaches. Toxicol. In Vitro 2013, 27, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundert-Remy, U.; Sonich-Mullin, C. The Use of Toxicokinetic and Toxicodynamic Data in Risk Assessment: An International Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2002, 288, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.M.; Buckley, N.A. Pharmacokinetic Considerations in Clinical Toxicology: Clinical Applications. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2007, 46, 897–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug Bioavailability. 2023.

- Li, W.; Picard, F. Toxicokinetics in Preclinical Drug Development of Small-molecule New Chemical Entities. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2023, 37, e5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Beaumont, K.; Maurer, T.S.; Di, L. Volume of Distribution in Drug Design: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5691–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Mahabadi, N. Volume of Distribution. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, X.; Pan, X.; Wang, B.; Ji, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.H. HobPre: Accurate Prediction of Human Oral Bioavailability for Small Molecules. J. Cheminformatics 2022, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón-Cano, G.; Molina, C.; Cabrera-Pérez, M.Á. ADME Prediction with KNIME: Development and Validation of a Publicly Available Workflow for the Prediction of Human Oral Bioavailability. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 2660–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, V. FP-ADMET: A Compendium of Fingerprint-Based ADMET Prediction Models. J. Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An Integrated Online Platform for Accurate and Comprehensive Predictions of ADMET Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, T. ADME Evaluation in Drug Discovery. 9. Prediction of Oral Bioavailability in Humans Based on Molecular Properties and Structural Fingerprints. Mol. Pharm. 2011, 8, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.T.; Sedykh, A.; Chakravarti, S.K.; Saiakhov, R.D.; Zhu, H. Critical Evaluation of Human Oral Bioavailability for Pharmaceutical Drugs by Using Various Cheminformatics Approaches. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musther, H.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Hatley, O.J.D.; Liu, B.; Rostami Hodjegan, A. Animal versus Human Oral Drug Bioavailability: Do They Correlate? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 57, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yan, Y.; Dai, S.; Shao, D.; Yi, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yan, J. Research on Prediction of Human Oral Bioavailability of Drugs Based on Improved Deep Forest. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2024, 133, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, F.; Jing, Y. In Silico Prediction of Volume of Distribution in Humans. Extensive Data Set and the Exploration of Linear and Nonlinear Methods Coupled with Molecular Interaction Fields Descriptors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 2042–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, F.; Bentzien, J.; Berellini, G.; Muegge, I. In Silico Models of Human PK Parameters. Prediction of Volume of Distribution Using an Extensive Data Set and a Reduced Number of Parameters. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gombar, V.K.; Hall, S.D. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Models of Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Clearance and Volume of Distribution. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, U.; Hellberg, S.; Alvarsson, J.; Arvidsson McShane, S.; Spjuth, O. In Silico Prediction of Volume of Distribution of Drugs in Man Using Conformal Prediction Performs on Par with Animal Data-Based Models. Xenobiotica 2021, 51, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, S.; Montanari, D.; Gleeson, M.P. Investigation of Factors Affecting the Performance of in Silico Volume Distribution QSAR Models for Human, Rat, Mouse, Dog & Monkey. Mol. Inform. 2019, 38, 1900059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, C.; Wang, H.; Meng, F. A Benchmarking Dataset with 2440 Organic Molecules for Volume Distribution at Steady State. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakkebæk, N.E.; Lindahl-Jacobsen, R.; Levine, H.; Andersson, A.-M.; Jørgensen, N.; Main, K.M.; Lidegaard, Ø.; Priskorn, L.; Holmboe, S.A.; Bräuner, E.V.; et al. Environmental Factors in Declining Human Fertility. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A.M.; Sonnenschein, C. Endocrine Disruptors: DDT, Endocrine Disruption and Breast Cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 507–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindel, J.J.; Newbold, R.; Schug, T.T. Endocrine Disruptors and Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, S.; Teixeira, E.; Gaspar, T.B.; Boaventura, P.; Soares, M.A.; Miranda-Alves, L.; Soares, P. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Endocrine Neoplasia: A Forty-Year Systematic Review. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.; Jeung, E.-B. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Disease Endpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsolaro, V.; Pasqualetti, G.; Niccolai, F.; Caraccio, N.; Monzani, F. Thyroid Disrupting Chemicals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, K.-U.; Brown, T.N.; Endo, S. Elimination Half-Life as a Metric for the Bioaccumulation Potential of Chemicals in Aquatic and Terrestrial Food Chains. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 1663–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallare, J.; Gerriets, V. Half Life. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aungst, B.J. Optimizing Oral Bioavailability in Drug Discovery: An Overview of Design and Testing Strategies and Formulation Options. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction 2018.

- Wang, J.; Krudy, G.; Xie, X.-Q.; Wu, C.; Holland, G. Genetic Algorithm-Optimized QSPR Models for Bioavailability, Protein Binding, and Urinary Excretion. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 2674–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendt, R.; Hofmann, U.; Schneider, A.R.P.; Schaeffeler, E.; Burghaus, R.; Yilmaz, A.; Blank, L.M.; Kerb, R.; Lippert, J.; Schlender, J.; et al. Data-driven Personalization of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model for Caffeine: A Systematic Assessment. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2021, 10, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2017; pp. 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Gély, C.A.; Lacroix, M.Z.; Roques, B.B.; Toutain, P.-L.; Gayrard, V.; Picard-Hagen, N. Comparison of Toxicokinetic Properties of Eleven Analogues of Bisphenol A in Pig after Intravenous and Oral Administrations. Environ. Int. 2023, 171, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, K.A.; Doerge, D.R.; Hunt, D.; Schurman, S.H.; Twaddle, N.C.; Churchwell, M.I.; Garantziotis, S.; Kissling, G.E.; Easterling, M.R.; Bucher, J.R.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Bisphenol A in Humans Following a Single Oral Administration. Environ. Int. 2015, 83, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeckelhuber, M.; Scherer, M.; Peschel, O.; Leibold, E.; Bracher, F.; Scherer, G.; Pluym, N. Human Metabolism and Urinary Excretion Kinetics of the UV Filter Uvinul A Plus® after a Single Oral or Dermal Dosage. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 227, 113509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, Å.; Wang, B.; Gerde, P.; Bergman, Å.; Yeung, L.W.Y. Bioavailability of Inhaled or Ingested PFOA Adsorbed to House Dust. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 78698–78710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustinoni, S.; Mercadante, R.; Lainati, G.; Cafagna, S.; Consonni, D. Kinetics of Excretion of the Perfluoroalkyl Surfactant cC6O4 in Humans. Toxics 2023, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, R.; Hagen, T.G.; Champness, D.; Sellier, A. Half-Lives of Several Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Cattle Serum and Tissues. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2022, 39, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, W.; Numtip, W.; Völkel, W.; Seckin, E.; Csanády, G.A.; Pütz, C.; Klein, D.; Fromme, H.; Filser, J.G. Kinetics of Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) and Mono(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Blood and of DEHP Metabolites in Urine of Male Volunteers after Single Ingestion of Ring-Deuterated DEHP. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 264, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency. 2025. Available online: Http://Echa.Europa.Eu/Web/Guest/Information-on-Chemicals/Registered-Substances.

- Sovino, H.; Sir-Petermann, T.; Devoto, L. Clomiphene Citrate and Ovulation Induction. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2002, 4, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cersosimo, R.J. Tamoxifen for Prevention of Breast Cancer. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003, 37, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L.R.; Goa, K.L. Toremifene: A Review of Its Pharmacological Properties and Clinical Efficacy in the Management of Advanced Breast Cancer. Drugs 1997, 54, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, I.; Novotarskyi, S.; Körner, R.; Pandey, A.K.; Rupp, M.; Teetz, W.; Brandmaier, S.; Abdelaziz, A.; Prokopenko, V.V.; Tanchuk, V.Y.; et al. Online Chemical Modeling Environment (OCHEM): Web Platform for Data Storage, Model Development and Publishing of Chemical Information. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2011, 25, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulton, A.; Bellis, L.J.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; Davies, M.; Hersey, A.; Light, Y.; McGlinchey, S.; Michalovich, D.; Al-Lazikani, B.; et al. ChEMBL: A Large-Scale Bioactivity Database for Drug Discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1100–D1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, M.V.S.; Obach, R.S.; Rotter, C.; Miller, H.R.; Chang, G.; Steyn, S.J.; El-Kattan, A.; Troutman, M.D. Physicochemical Space for Optimum Oral Bioavailability: Contribution of Human Intestinal Absorption and First-Pass Elimination. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2023 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1373–D1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutain, P.L.; Bousquet-Mélou, A. Volumes of Distribution. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 27, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, H.; Tian, Y.-S.; Kawashita, N.; Takagi, T. Mordred: A Molecular Descriptor Calculator. J. Cheminformatics 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.-M.; Tuleau-Malot, C. VSURF: An R Package for Variable Selection Using Random Forests. R J. 2015, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Guidance Document on the Validation of (Quantitative) Structure-Activity Relationship [(Q)SAR] Models; OECD Series on Testing and Assessment; OECD, 2014; ISBN 978-92-64-08544-2.

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased Boosting with Categorical Features 2019.

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, August 13, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, E.; Greenman, K.P.; Chung, Y.; Li, S.-C.; Graff, D.E.; Vermeire, F.H.; Wu, H.; Green, W.H.; McGill, C.J. Chemprop: A Machine Learning Package for Chemical Property Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, T.; Gini, G.; Golbamaki Bakhtyari, N.; Benfenati, E. Mining Toxicity Structural Alerts from SMILES: A New Way to Derive Structure Activity Relationships. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining (CIDM); IEEE: Paris, France, April, 2011; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, T.; Cattaneo, D.; Gini, G.; Golbamaki Bakhtyari, N.; Manganaro, A.; Benfenati, E. Automatic Knowledge Extraction from Chemical Structures: The Case of Mutagenicity Prediction. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2013, 24, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H.L. The Generation of a Unique Machine Description for Chemical Structures-A Technique Developed at Chemical Abstracts Service. J. Chem. Doc. 1965, 5, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, G. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics. 2006. There Is No Corresponding Record for This Reference. Available online: Https://Www.Rdkit.Org/.

- Dietterich, T.G. Ensemble Methods in Machine Learning. In Multiple Classifier Systems; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000; ISBN 978-3-540-67704-8. [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini, R.; Ballabio, D.; Grisoni, F. Beware of Unreliable Q 2 ! A Comparative Study of Regression Metrics for Predictivity Assessment of QSAR Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 1905–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komissarov, L.; Manevski, N.; Groebke Zbinden, K.; Schindler, T.; Zitnik, M.; Sach-Peltason, L. Actionable Predictions of Human Pharmacokinetics at the Drug Design Stage 2024.

- Netzeva, T.I.; Worth, A.P.; Aldenberg, T.; Benigni, R.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Gramatica, P.; Jaworska, J.S.; Kahn, S.; Klopman, G.; Marchant, C.A.; et al. Current Status of Methods for Defining the Applicability Domain of (Quantitative) Structure-Activity Relationships: The Report and Recommendations of ECVAM Workshop 52, Altern. Lab. Anim. 2005, 33, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahigara, F.; Mansouri, K.; Ballabio, D.; Mauri, A.; Consonni, V.; Todeschini, R. Comparison of Different Approaches to Define the Applicability Domain of QSAR Models. Molecules 2012, 17, 4791–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetko, I.V.; Sushko, I.; Pandey, A.K.; Zhu, H.; Tropsha, A.; Papa, E.; Öberg, T.; Todeschini, R.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A. Critical Assessment of QSAR Models of Environmental Toxicity against Tetrahymena Pyriformis: Focusing on Applicability Domain and Overfitting by Variable Selection. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchiandi, J.; Alghamdi, W.; Dagnino, S.; Green, M.P.; Clarke, B.O. Exposure to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals from Beverage Packaging Materials and Risk Assessment for Consumers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Bharat, G.K.; Gaonkar, O.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Chandra, S.; Steindal, E.H.; Nizzetto, L. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals Used as Common Plastic Additives: Levels, Profiles, and Human Dietary Exposure from the Indian Food Basket. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaider, L.A.; Balan, S.A.; Blum, A.; Andrews, D.Q.; Strynar, M.J.; Dickinson, M.E.; Lunderberg, D.M.; Lang, J.R.; Peaslee, G.F. Fluorinated Compounds in U.S. Fast Food Packaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undas, A.K.; Groenen, M.; Peters, R.J.B.; Van Leeuwen, S.P.J. Safety of Recycled Plastics and Textiles: Review on the Detection, Identification and Safety Assessment of Contaminants. Chemosphere 2023, 312, 137175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.M.; Wong, L.-Y.; Ye, X.; Reidy, J.A.; Needham, L.L. Concentrations of the Sunscreen Agent Benzophenone-3 in Residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Lim, Y.-H.; Hong, Y.-C. Ten-Year Trends in Urinary Concentrations of Triclosan and Benzophenone-3 in the General U.S. Population from 2003 to 2012. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Alvarado, L.; Kupesic-Plavsic, S. Exposure of U.S. Population to Endocrine Disruptive Chemicals (Parabens, Benzophenone-3, Bisphenol-A and Triclosan) and Their Associations with Female Infertility. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, K.; Kleinstreuer, N.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Alberga, D.; Alves, V.M.; Andersson, P.L.; Andrade, C.H.; Bai, F.; Balabin, I.; Ballabio, D.; et al. CoMPARA: Collaborative Modeling Project for Androgen Receptor Activity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 27002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfenati, E.; Manganaro, A.; Gini, G. VEGA-QSAR: AI inside a Platform for Predictive Toxicology Proceedings of the Workshop “Popularize Artificial Intelligence 2013”, th 2013, Turin, Italy Published on CEUR Workshop Proceedings Vol-1107. 5 December.

- Manganelli, S.; Roncaglioni, A.; Mansouri, K.; Judson, R.S.; Benfenati, E.; Manganaro, A.; Ruiz, P. Development, Validation and Integration of in Silico Models to Identify Androgen Active Chemicals. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Endpoint | Dataset | Modeling algorithm | # Chemicals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral bioavailability | Training | Regression | 1213 |

| Classification (50% threshold) | 1307 | ||

| Binary Classification (30%,60% thresholds) | 1244 | ||

| Validation | Regression/ Binary Classification/ Multiclass Classification | 405 | |

| VDss | Training | Regression/Binary Classification/Multiclass Classification | 1167 |

| Validation 1 | 390 | ||

| Validation 2 | 34 |

| Metric | Performance for regression (R) | Performance for binary classification (BC) | Performance for multiclass classification (MC) | CV Performance for regression (R) | CV Performance for binary classification (BC) | CV Performance for multiclass classification (MC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation set | CV | |||||

| Model | R-CatBoost | BC-CatBoost | MC-CatBoost | R-CatBoost | BC-CatBoost | MC-CatBoost |

| Regression metrics | ||||||

| RMSE | 25.86 | NA | 27.71±0.98 | |||

| R² | 0.42 | NA | NA | 0.38±0.04 | NA | NA |

| MAE | 20.09 | NA | NA | 20.90±0.82 | NA | NA |

| MedAE | 15.92 | NA | NA | 17.01±1.11 | NA | NA |

| Q²F3 | 0.39 | NA | NA | 0.34±0.05 | NA | NA |

| Binary Classification metrics | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 0.78 | 0.79 | NA | 0.75±0.03 | 0.78±0.03 | NA |

| Specificity | 0.76 | 0.68 | NA | 0.72±0.03 | 0.69±0.04 | NA |

| Balanced accuracy | 0.77 | 0.74 | NA | 0.74±0.02 | 0.74±0.02 | NA |

| Multiclass Classification metrics | ||||||

| Sensitivity (<30%) | 0.46 | NA | 0.67 | 0.45±0.05 | NA | 0.64±0.05 |

| Specificity (<30%) | 0.91 | NA | 0.86 | 0.93±0.03 | NA | 0.83±0.03 |

| Balanced accuracy (<30%) | 0.68 | NA | 0.77 | 0.63±0.02 | NA | 0.74±0.02 |

| Sensitivity [30%-60%] | 0.58 | NA | 0.25 | 0.69±0.02 | NA | 0.31±0.05 |

| Specificity [30%-60%] | 0.63 | NA | 0.89 | 0.63±0.03 | NA | 0.88±0.02 |

| Balanced accuracy [30%-60%] | 0.60 | NA | 0.57 | 0.63±0.03 | NA | 0.60±0.03 |

| Sensitivity (>60%) | 0.63 | NA | 0.83 | 0.63±0.04 | NA | 0.79±0.03 |

| Specificity (>60%) | 0.84 | NA | 0.67 | 0.84±0.03 | NA | 0.70±0.03 |

| Balanced accuracy (>60%) | 0.74 | NA | 0.75 | 0.74±0.02 | NA | 0.74±0.02 |

| Macro Sensitivity | 0.56 | NA | 0.58 | 0.57±0.03 | NA | 0.58±0.02 |

| Macro Specificity | 0.79 | NA | 0.81 | 0.80±0.01 | NA | 0.81±0.01 |

| Macro Balanced accuracy | 0.68 | NA | 0.70 | 0.68±0.02 | NA | 0.69±0.02 |

| Micro Sensitivity | 0.56 | NA | 0.64 | 0.57±0.03 | NA | 0.63±0.02 |

| Micro Specificity | 0.78 | NA | 0.82 | 0.79±0.01 | NA | 0.82±0.01 |

| Metric | Regression model performance | Classification model performance | Classification multiclass model performance | CV Regression model performance | CV Classification model performance | CV Classification multiclass model performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation set 1 | CV | |||||

| Model | R-RF | BC-Chemprop | MC-Chemprop | R-RF | BC-Chemprop | MC-Chemprop |

| Regression metrics | ||||||

| GMFE | 2.35 | NA | NA | 2.19±0.08 | NA | NA |

| Binary Classification metrics | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 0.79 | 0.77 | NA | 0.79±0.03 | 0.73±0.06 | NA |

| Specificity | 0.71 | 0.75 | NA | 0.75±0.03 | 0.83±0.04 | NA |

| Balanced accuracy | 0.75 | 0.76 | NA | 0.77±0.02 | 0.78±0.03 | NA |

| Multiclass Classification metrics | ||||||

| Sensitivity (<0.6) | 0.62 | NA | 0.68 | 0.66±0.04 | NA | 0.71±0.05 |

| Specificity (<0.6) | 0.91 | NA | 0.76 | 0.90±0.02 | NA | 0.87±0.03 |

| Balanced accuracy (<0.6) | 0.76 | NA | 0.45 | 0.78±0.02 | NA | 0.79±0.03 |

| Sensitivity [0.6-5] | 0.82 | NA | 0.89 | 0.83±0.03 | NA | 0.76±0.05 |

| Specificity [0.6-5] | 0.51 | NA | 0.63 | 0.57±0.04 | NA | 0.66±0.05 |

| Balanced accuracy [0.6-5] | 0.67 | NA | 0.94 | 0.70±0.02 | NA | 0.71±0.03 |

| Sensitivity (>5) | 0.22 | NA | 0.78 | 0.32±0.06 | NA | 0.42±.09 |

| Specificity (>5) | 0.97 | NA | 0.70 | 0.97±0.01 | NA | 0.94±0.02 |

| Balanced accuracy (>5) | 0.60 | NA | 0.69 | 0.64±0.03 | NA | 0.68±0.04 |

| Macro Sensitivity | 0.56 | NA | 0.63 | 0.60±0.03 | NA | 0.63±0.03 |

| Macro Specificity | 0.80 | NA | 0.82 | 0.81±0.01 | NA | 0.82±0.02 |

| Macro Balanced accuracy | 0.68 | NA | 0.72 | 0.71±0.02 | NA | 0.73±0.02 |

| Micro Sensitivity | 0.65 | NA | 0.68 | 0.68±0.02 | NA | 0.69±0.03 |

| Micro Specificity | 0.83 | NA | 0.84 | 0.84±0.01 | NA | 0.84±0.01 |

| Micro Balanced accuracy | 0.74 | NA | 0.76 | 0.76±0.02 | NA | 0.77±0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).