Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Role of the EDA Pathway in Skeletal Formation

3. Cross-Talk Between EDA and Major Skeletogenic Pathways

3.1. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Signaling Pathways

3.2. Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling Pathways

3.3. Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

3.4. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

3.5. Notch Signaling Pathway

4. Cross-Talk Between EDA and Growth Factor-Mediated Signals

4.1. Fibroblast Growth Factor Signaling Pathway

4.2. Insulin-Like Growth Factor Signaling Pathway

4.3. Signals Mediated by MAPKs

5. Cross-Talk Between EDA and Signals Mediated by Nuclear Receptors

5.1. Retinoic Acid Signaling Pathway

5.2. Aryl Hydrocarbon Signaling Pathway

5.3. Glucocorticoid Signaling Pathway

5.4. Estrogen Signaling Pathway

6. Cross-Talk Between EDA and Calcium Dependent Pathways

6.1. Signaling Pathways Mediated by Nuclear Factor of Activated T-Cells

6.2. Parathyroid Hormone Signaling Pathway

6.3. Calmodulin Signaling Pathway

6.4. Endothelin Signaling Pathway

7. Potential Cross-Talk Between EDA and Non-Canonical Microenvironment-Responsive Pathways Affecting Skeletogenesis

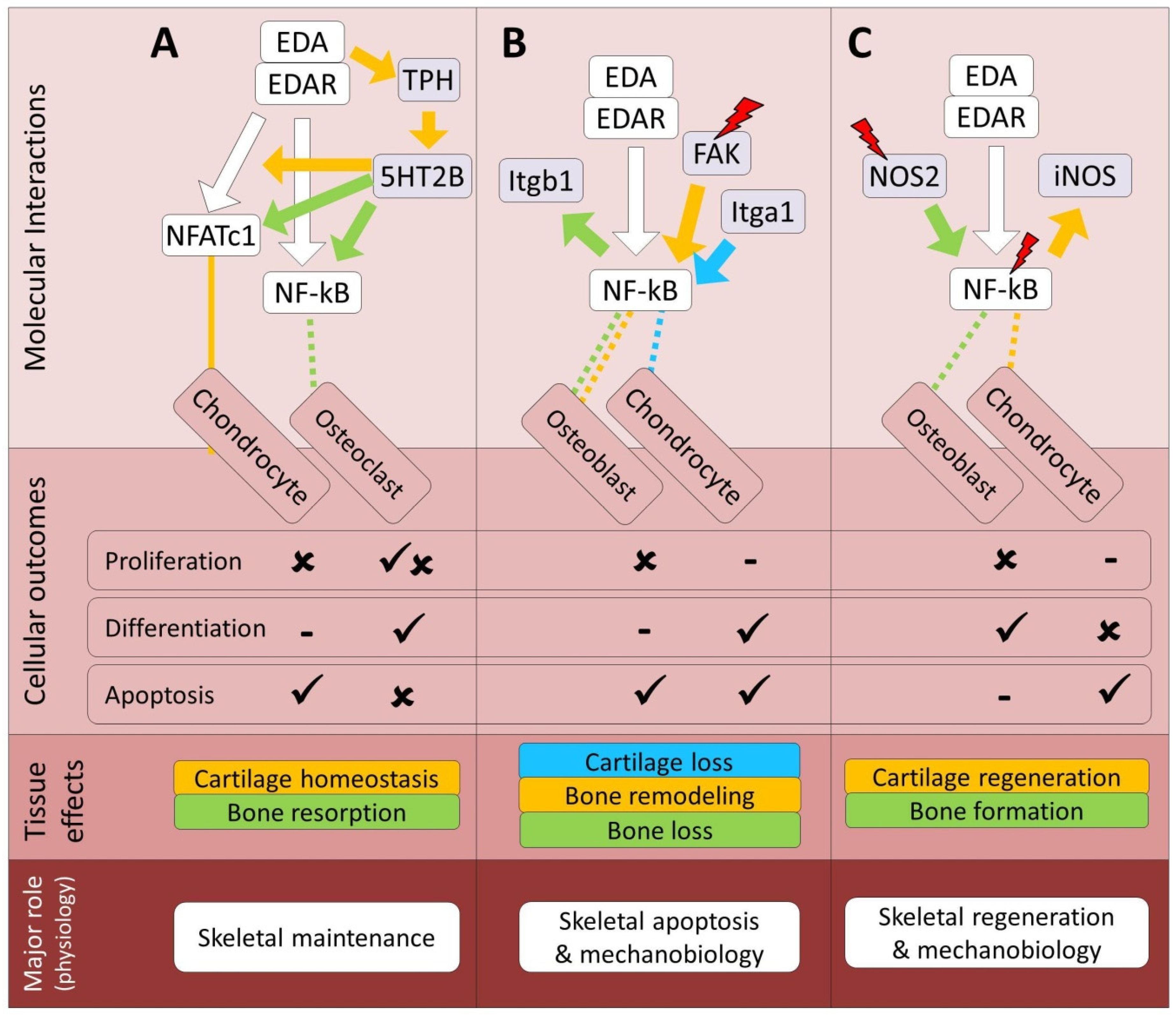

7.1. Serotonin Signaling Pathway

7.2. Integrin Signaling Pathway

7.3. Nitric Oxide Signaling Pathway

Conclusion

References

- C.Y. Cui, D. Schlessinger, EDA Signaling and Skin Appendage Development, Cell Cycle 5 (2006) 2477–2483. [CrossRef]

- T. Mustonen, M. Ilmonen, M. Pummila, A.T. Kangas, J. Laurikkala, R. Jaatinen, J. Pispa, O. Gaide, P. Schneider, I. Thesleff, M.L. Mikkola, Ectodysplasin A1 promotes placodal cell fate during early morphogenesis of ectodermal appendages, Development 131 (2004) 4907–4919. [CrossRef]

- A. Sadier, L. Viriot, S. Pantalacci, V. Laudet, The ectodysplasin pathway: From diseases to adaptations, Trends Genet. 30 (2014) 24–31. [CrossRef]

- P. Schneider, S.L. Street, O. Gaide, S. Hertig, A. Tardivel, J. Tschopp, L. Runkel, K. Alevizopoulos, B.M. Ferguson, J. Zonana, Mutations leading to X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia affect three major functional domains in the tumor necrosis factor family member ectodysplasin-A, J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2001) 18819–18827. [CrossRef]

- C. Cluzeau, S. Hadj-Rabia, M. Jambou, S. Mansour, P. Guigue, S. Masmoudi, E. Bal, N. Chassaing, M.C. Vincent, G. Viot, F. Clauss, M.C. Manière, S. Toupenay, M. Le Merrer, S. Lyonnet, V. Cormier-Daire, J. Amiel, L. Faivre, Y. De Prost, A. Munnich, J.P. Bonnefont, C. Bodemer, A. Smahi, Only four genes (EDA1, EDAR, EDARADD, and WNT10A) account for 90% of hypohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia cases, Hum. Mutat. 32 (2011) 70–72. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cai, X. Deng, J. Jia, D. Wang, G. Yuan, Ectodysplasin A/Ectodysplasin A Receptor System and Their Roles in Multiple Diseases, Front. Physiol. 12 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Xing, Y. Liu, J. Wu, C. Song, B. Jiang, Spatial and Temporal Expression of Ectodysplasin-A Signaling Pathway Members During Mandibular Condylar Development in Postnatal Mice 71 (2023) 631-642. [CrossRef]

- O. Montonen, S. Ezer, U.K. Saarialho-Kere, R. Herva, M.-L. Karjalainen-Lindsberg, I. Kaitila, D. Schlessinger, A.K. Srivastava, I. Thesleff, J. Kere, Ectodysplasin A1 Deficiency Leads to Osteopetrosis-like Changes in Bones of the Skull Associated with Diminished Osteoclastic Activity, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, Vol. 23, Page 12189 23 (2022) 12189. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Mikkola, I. Thesleff, Ectodysplasin signaling in development, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14 (2003) 211–224. [CrossRef]

- E.P. Ahi, Signalling pathways in trophic skeletal development and morphogenesis: Insights from studies on teleost fish, Dev. Biol. 420 (2016) 11–31. [CrossRef]

- S. Dash, P.A. Trainor, The development, patterning and evolution of neural crest cell differentiation into cartilage and bone, Bone 137 (2020) 115409. [CrossRef]

- O. Elomaa, K. O. Elomaa, K. Pulkkinen, U. Hannelius, M. Mikkola, U. Saarialho-Kere, J. Kere, Ectodysplasin is released by proteolytic shedding and binds to the EDAR protein, Hum. Mol. Genet. 10 (2001) 953–962. [CrossRef]

- K. Verhelst, S. Gardam, A. Borghi, M. Kreike, I. Carpentier, R. Beyaert, XEDAR activates the non-canonical NF-κB pathway, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 465 (2015) 275–280. [CrossRef]

- H. Fujikawa, M. Farooq, A. Fujimoto, M. Ito, Y. Shimomura, Functional studies for the TRAF6 mutation associated with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, Br. J. Dermatol. 168 (2013) 629–633. [CrossRef]

- A. Morlon, A. Munnich, A. Smahi, TAB2, TRAF6 and TAK1 are involved in NF-κB activation induced by the TNF-receptor, Edar and its adaptator Edaradd, Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 (2005) 3751–3757. [CrossRef]

- T. Mustonen, J. Pispa, M.L. Mikkola, M. Pummila, A.T. Kangas, L. Pakkasjärvi, R. Jaatinen, I. Thesleff, Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1, Dev. Biol. 259 (2003) 123–136. [CrossRef]

- C. Schweikl, S. Maier-Wohlfart, H. Schneider, J. Park, Ectodysplasin A1 Deficiency Leads to Osteopetrosis-like Changes in Bones of the Skull Associated with Diminished Osteoclastic Activity, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, Vol. 23, Page 12189 23 (2022) 12189. [CrossRef]

- C.S. Kossel, M. Wahlbuhl, S. Schuepbach-Mallepell, J. Park, C. Kowalczyk-Quintas, M. Seeling, K. von der Mark, P. Schneider, H. Schneider, Correction of Vertebral Bone Development in Ectodysplasin A1-Deficient Mice by Prenatal Treatment With a Replacement Protein, Front. Genet. 12 (2021) 709736. [CrossRef]

- B. Chang, V. Punj, M. Shindo, P.M. Chaudhary, Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of ectodysplasin-A2 results in induction of apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in osteosarcoma cell lines, Cancer Gene Ther. 2007 1411 14 (2007) 927–933. [CrossRef]

- M. Pummila, I. Fliniaux, R. Jaatinen, M.J. James, J. Laurikkala, P. Schneider, I. Thesleff, M.L. Mikkola, Ectodysplasin has a dual role in ectodermal organogenesis: inhibition of Bmp activity and induction of Shh expression, Development 134 (2007) 117–125. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Harris, N. Rohner, H. Schwarz, S. Perathoner, P. Konstantinidis, C. Nüsslein-Volhard, Zebrafish eda and edar Mutants Reveal Conserved and Ancestral Roles of Ectodysplasin Signaling in Vertebrates, PLoS Genet. 4 (2008) e1000206. [CrossRef]

- A. Williams, E.C.Y. Wang, L. Thurner, C.J. Liu, Review: Novel Insights Into Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor, Death Receptor 3, and Progranulin Pathways in Arthritis and Bone Remodeling, Arthritis Rheumatol. (Hoboken, N.J.) 68 (2016) 2845. [CrossRef]

- F. Clauss, M.C. Manière, F. Obry, E. Waltmann, S. Hadj-Rabia, C. Bodemer, Y. Alembik, H. Lesot, M. Schmittbuhl, Dento-craniofacial phenotypes and underlying molecular mechanisms in hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED): a review, J. Dent. Res. 87 (2008) 1089–1099. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Costa, D.M. Power, Skin and scale regeneration after mechanical damage in a teleost, Mol. Immunol. 95 (2018) 73–82. [CrossRef]

- F. Tonelli, J.W. Bek, R. Besio, A. De Clercq, L. Leoni, P. Salmon, P.J. Coucke, A. Willaert, A. Forlino, Zebrafish: A Resourceful Vertebrate Model to Investigate Skeletal Disorders, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11 (2020) 555577. [CrossRef]

- J. Kere, A.K. Srivastava, O. Montonen, J. Zonana, N. Thomas, B. Ferguson, F. Munoz, D. Morgan, A. Clarke, P. Baybayan, E.Y. Chen, S. Ezer, U. Saarialho-Kere, A. De La Chapelle, D. Schlessinger, X–linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein, Nat. Genet. 1996 134 13 (1996) 409–416. [CrossRef]

- A.W. Monreal, B.M. Ferguson, D.J. Headon, S.L. Street, P.A. Overbeek, J. Zonana, Mutations in the human homologue of mouse dl cause autosomal recessive and dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, Nat. Genet. 1999 224 22 (1999) 366–369. [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Sire, A. Huysseune, Formation of dermal skeletal and dental tissues in fish: A comparative and evolutionary approach, Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 78 (2003). [CrossRef]

- P.C.J. Donoghue, I.J. Sansom, Origin and early evolution of vertebrate skeletonization, Microsc. Res. Tech. 59 (2002) 352–372. [CrossRef]

- T.W.P. Wood, T. Nakamura, Problems in Fish-to-Tetrapod Transition: Genetic Expeditions Into Old Specimens, Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 6 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N.M. O’brown, B.R. Summers, F.C. Jones, S.D. Brady, D.M. Kingsley, A recurrent regulatory change underlying altered expression and Wnt response of the stickleback armor plates gene EDA, Elife 2015 (2015). [CrossRef]

- T.G. Laurentino, N. Boileau, F. Ronco, D. Berner, The ectodysplasin-A receptor is a candidate gene for lateral plate number variation in stickleback fish., G3 (Bethesda). 12 (2022) jkac077–jkac077. [CrossRef]

- M. Wagner, S. Bračun, A. Duenser, C. Sturmbauer, W. Gessl, E.P. Ahi, Expression variations in ectodysplasin-A gene (eda) may contribute to morphological divergence of scales in haplochromine cichlids, BMC Ecol. Evol. 22 (2022) 28. [CrossRef]

- M. de Caestecker, The transforming growth factor-β superfamily of receptors, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 15 (2004) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- J.G. Kim, Y.A. Rim, J.H. Ju, The Role of Transforming Growth Factor Beta in Joint Homeostasis and Cartilage Regeneration, Tissue Eng. Part C. Methods 28 (2022) 570–587. [CrossRef]

- E.P. Ahi, Regulation of Skeletogenic Pathways by m6A RNA Modification: A Comprehensive Review, Calcif. Tissue Int. 2025 1161 116 (2025) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Patil, R.B. Sable, R.M. Kothari, An update on transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β): Sources, types, functions and clinical applicability for cartilage/bone healing, J. Cell. Physiol. 226 (2011) 3094–3103. [CrossRef]

- A. Machiya, S. Tsukamoto, S. Ohte, M. Kuratani, N. Suda, T. Katagiri, Smad4-dependent transforming growth factor-β family signaling regulates the differentiation of dental epithelial cells in adult mouse incisors, Bone 137 (2020) 115456. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, D. Rigueur, K.M. Lyons, TGFβ as a gatekeeper of BMP action in the developing growth plate, Bone 137 (2020) 115439. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, S. Xiang, B. Wang, H. Lin, S. Kihara, H. Sun, P.G. Alexander, R.S. Tuan, TGF-β1 plays a protective role in glucocorticoid-induced dystrophic calcification, Bone 136 (2020) 115355. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Ekholm, L. Ravanti, V.M. Kähäri, P. Paavolainen, R.P.K. Penttinen, Expression of extracellular matrix genes: transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and ras in tibial fracture healing of lathyritic rats, Bone 27 (2000) 551–557. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Li, M.I. Koster, X.J. Wang, Roles of TGFβ signaling in epidermal/appendage development, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14 (2003) 99–111. [CrossRef]

- M. Bei, Molecular genetics of tooth development, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19 (2009) 504–510. [CrossRef]

- S. Trakanant, J. Nihara, M. Kawasaki, F. Meguro, A. Yamada, K. Kawasaki, I. Saito, M. Takeyasu, A. Ohazama, Molecular mechanisms in palatal rugae development, J. Oral Biosci. 62 (2020) 30–35. [CrossRef]

- G.R. Gipson, E.J. Goebel, K.N. Hart, E.C. Kappes, C. Kattamuri, J.C. McCoy, T.B. Thompson, Structural perspective of BMP ligands and signaling, Bone 140 (2020) 115549. [CrossRef]

- T.K. Sampath, A.H. Reddi, Discovery of bone morphogenetic proteins – A historical perspective, Bone 140 (2020) 115548. [CrossRef]

- G. Sanchez-Duffhues, E. Williams, M.J. Goumans, C.H. Heldin, P. ten Dijke, Bone morphogenetic protein receptors: Structure, function and targeting by selective small molecule kinase inhibitors, Bone 138 (2020) 115472. [CrossRef]

- J. Gluhak-Heinrich, D. Guo, W. Yang, M.A. Harris, A. Lichtler, B. Kream, J. Zhang, J.Q. Feng, L.C. Smith, P. Dechow, S.E. Harris, New roles and mechanism of action of BMP4 in postnatal tooth cytodifferentiation, Bone 46 (2010) 1533–1545. [CrossRef]

- C. da Silva Madaleno, J. Jatzlau, P. Knaus, BMP signalling in a mechanical context – Implications for bone biology, Bone 137 (2020) 115416. [CrossRef]

- D.M. Medeiros, J.G. Crump, New perspectives on pharyngeal dorsoventral patterning in development and evolution of the vertebrate jaw., Dev. Biol. 371 (2012) 121–35. [CrossRef]

- T. Katagiri, T. Watabe, Bone Morphogenetic Proteins, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8 (2016) a021899. [CrossRef]

- Y. Iida, K. Hibiya, K. Inohaya, A. Kudo, Eda/Edar signaling guides fin ray formation with preceding osteoblast differentiation, as revealed by analyses of the medaka all-fin less mutant afl, Dev. Dyn. 243 (2014) 765–777. [CrossRef]

- C.C. Mandal, F. Das, S. Ganapathy, S.E. Harris, G.G. Choudhury, N. Ghosh-Choudhury, Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) activates NFATc1 transcription factor via an autoregulatory loop involving Smad/Akt/Ca2+ signaling, J. Biol. Chem. 291 (2016) 1148–1161. [CrossRef]

- W. Shen, Y. Wang, Y. Liu, H. Liu, H. Zhao, G. Zhang, M.L. Snead, D. Han, H. Feng, Functional Study of Ectodysplasin-A Mutations Causing Non-Syndromic Tooth Agenesis, PLoS One 11 (2016) e0154884. [CrossRef]

- H.W.A. Ehlen, L.A. Buelens, A. Vortkamp, Hedgehog signaling in skeletal development, Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 78 (2006) 267–279. [CrossRef]

- D. Huangfu, K. V Anderson, Signaling from Smo to Ci/Gli: conservation and divergence of Hedgehog pathways from Drosophila to vertebrates., Development 133 (2006) 3–14. [CrossRef]

- S. Ohba, Hedgehog Signaling in Skeletal Development: Roles of Indian Hedgehog and the Mode of Its Action, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 21, Page 6665 21 (2020) 6665. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, P. Andre, L. Ye, Y.Z. Yang, The Hedgehog signalling pathway in bone formation, Int. J. Oral Sci. 2015 72 7 (2015) 73–79. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, P.P.R. Iyyanar, Y. Lan, R. Jiang, Sonic hedgehog signaling in craniofacial development, Differentiation 133 (2023) 60–76. [CrossRef]

- A. Marumoto, R. Milani, R.A. da Silva, C.J. da Costa Fernandes, J.M. Granjeiro, C. V. Ferreira, M.P. Peppelenbosch, W.F. Zambuzzi, Phosphoproteome analysis reveals a critical role for hedgehog signalling in osteoblast morphological transitions, Bone 103 (2017) 55–63. [CrossRef]

- C. Kan, L. Chen, Y. Hu, N. Ding, Y. Li, T.L. McGuire, H. Lu, J.A. Kessler, L. Kan, Gli1-labeled adult mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells and hedgehog signaling contribute to endochondral heterotopic ossification, Bone 109 (2018) 71–79. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Aman, A.N. Fulbright, D.M. Parichy, Wnt/β-catenin regulates an ancient signaling network during zebrafish scale development, Elife 7 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S.-W. Cho, J.C. van Rijssel, F. Witte, M.A.G. de Bakker, M.K. Richardson, The sonic hedgehog signaling pathway and the development of pharyngeal arch Derivatives in Haplochromis piceatus, a Lake Victoria cichlid, J. Oral Biosci. 57 (2015) 148–156. [CrossRef]

- T. Shimo, K. Matsumoto, K. Takabatake, E. Aoyama, Y. Takebe, S. Ibaragi, T. Okui, N. Kurio, H. Takada, K. Obata, P. Pang, M. Iwamoto, H. Nagatsuka, A. Sasaki, The Role of Sonic Hedgehog Signaling in Osteoclastogenesis and Jaw Bone Destruction, PLoS One 11 (2016) e0151731. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, Y. Yang, Z. Liao, Q. Liu, X. Lei, M. Li, Saijilafu, Z. Zhang, D. Hong, M. Zhu, B. Li, H. Yang, J. Chen, Genetic and pharmacological activation of Hedgehog signaling inhibits osteoclastogenesis and attenuates titanium particle-induced osteolysis partly through suppressing the JNK/c-Fos-NFATc1 cascade, Theranostics 10 (2020) 6638. [CrossRef]

- D. Schupbach, M. Comeau-Gauthier, E. Harvey, G. Merle, Wnt modulation in bone healing, Bone 138 (2020) 115491. [CrossRef]

- T.A. Burgers, B.O. Williams, Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling within and from osteocytes, Bone 54 (2013) 244–249. [CrossRef]

- D.G. Monroe, M.E. McGee-Lawrence, M.J. Oursler, J.J. Westendorf, Update on Wnt signaling in bone cell biology and bone disease, Gene 492 (2012) 1–18. [CrossRef]

- T. Oichi, S. Otsuru, Y. Usami, M. Enomoto-Iwamoto, M. Iwamoto, Wnt signaling in chondroprogenitors during long bone development and growth, Bone 137 (2020) 115368. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Choi, A.G. Robling, The Wnt pathway: An important control mechanism in bone’s response to mechanical loading, Bone 153 (2021) 116087. [CrossRef]

- L. Hu, W. Chen, A. Qian, Y.P. Li, Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone formation, homeostasis, and disease, Bone Res. 2024 121 12 (2024) 1–33. [CrossRef]

- P.J. Niziolek, T.L. Farmer, Y. Cui, C.H. Turner, M.L. Warman, A.G. Robling, High-bone-mass-producing mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway result in distinct skeletal phenotypes, Bone 49 (2011) 1010–1019. [CrossRef]

- D. yu Bao, Y. Yang, X. Tong, H. yan Qin, Activation of wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway down regulated osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived stem cells in an anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia patient with EDA/EDAR/EDARADD mutation, Heliyon 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- H.J. Won, J.W. Kim, H.S. Won, J.O. Shin, Gene Regulatory Networks and Signaling Pathways in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate: A Comprehensive Review, Cells 2023, Vol. 12, Page 1954 12 (2023) 1954. [CrossRef]

- M.N. Evanitsky, S. Di Talia, An active traveling wave of Eda/NF-κB signaling controls the timing and hexagonal pattern of skin appendages in zebrafish, Dev. 150 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Liu, Y. Zhao, Y. Pei, F. Lian, H. Lin, Role of the NF-kB signalling pathway in heterotopic ossification: biological and therapeutic significance, Cell Commun. Signal. 2024 221 22 (2024) 1–26. [CrossRef]

- E. Horváth, Á. Sólyom, J. Székely, E.E. Nagy, H. Popoviciu, Inflammatory and Metabolic Signaling Interfaces of the Hypertrophic and Senescent Chondrocyte Phenotypes Associated with Osteoarthritis, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, Vol. 24, Page 16468 24 (2023) 16468. [CrossRef]

- K.S. Alharbi, O. Afzal, A.S.A. Altamimi, W.H. Almalki, I. Kazmi, F.A. Al-Abbasi, S.I. Alzarea, H.A. Makeen, M. Albratty, Potential role of nutraceuticals via targeting a Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB pathway in treatment of osteoarthritis, J. Food Biochem. 46 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y.Q. Liu, Z.L. Hong, L. Bin Zhan, H.Y. Chu, X.Z. Zhang, G.H. Li, Wedelolactone enhances osteoblastogenesis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway but suppresses osteoclastogenesis by NF-κB/c-fos/NFATc1 pathway, Sci. Reports 2016 61 6 (2016) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Weivoda, M. Ruan, C.M. Hachfeld, L. Pederson, A. Howe, R.A. Davey, J.D. Zajac, Y. Kobayashi, B.O. Williams, J.J. Westendorf, S. Khosla, M.J. Oursler, Wnt Signaling Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation by Activating Canonical and Noncanonical cAMP/PKA Pathways, J. Bone Miner. Res. 31 (2016) 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kobayashi, S. Uehara, M. Koide, N. Takahashi, The regulation of osteoclast differentiation by Wnt signals, Bonekey Rep. 4 (2015) 713. [CrossRef]

- N. Takahashi, Regulatory Mechanism of Osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt Signals, Front. Biosci. 16 (2011) 21. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Bray, Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7 (2006) 678–89. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, E. Canalis, Notch and the regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function, Bone 138 (2020) 115474. [CrossRef]

- T.J. Mead, K.E. Yutzey, Notch signaling and the developing skeleton., Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 727 (2012) 114–30. [CrossRef]

- A. Kamalakar, J.M. McKinney, D. Salinas Duron, A.M. Amanso, S.A. Ballestas, H. Drissi, N.J. Willett, P. Bhattaram, A.J. García, L.B. Wood, S.L. Goudy, JAGGED1 stimulates cranial neural crest cell osteoblast commitment pathways and bone regeneration independent of canonical NOTCH signaling, Bone 143 (2021) 115657. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Oldershaw, T.E. Hardingham, Notch signaling during chondrogenesis of human bone marrow stem cells, Bone 46 (2010) 286–293. [CrossRef]

- E. Canalis, L. Schilling, E. Denker, C. Stoddard, J. Yu, A NOTCH2 pathogenic variant and HES1 regulate osteoclastogenesis in induced pluripotent stem cells, Bone 191 (2025) 117334. [CrossRef]

- F. Engin, B. Lee, NOTCHing the bone: Insights into multi-functionality, Bone 46 (2010) 274–280. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Rodríguez-Ramírez, M. Hiltbrunner, V. Saladin, S. Walker, A. Urrutia, C.L. Peichel, Molecular mechanisms of Eda-mediated adaptation to freshwater in threespine stickleback, Mol. Ecol. 00 (2023) 1–19. [CrossRef]

- T. Shono, A.P. Thiery, R.L. Cooper, D. Kurokawa, R. Britz, M. Okabe, G.J. Fraser, Evolution and Developmental Diversity of Skin Spines in Pufferfishes, IScience 19 (2019) 1248–1259. [CrossRef]

- H. Fukushima, A. Nakao, F. Okamoto, M. Shin, H. Kajiya, S. Sakano, A. Bigas, E. Jimi, K. Okabe, The association of Notch2 and NF-kappaB accelerates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis., Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 (2008) 6402–12. [CrossRef]

- X.W. Dou, W. Park, S. Lee, Q.Z. Zhang, L.R. Carrasco, A.D. Le, Loss of Notch3 Signaling Enhances Osteogenesis of Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Mandibular Torus, J. Dent. Res. 96 (2017) 347–354. [CrossRef]

- S. Zanotti, A. Smerdel-Ramoya, E. Canalis, Reciprocal regulation of Notch and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) c1 transactivation in osteoblasts, J. Biol. Chem. 286 (2011) 4576–4588. [CrossRef]

- X. Tu, J. Chen, J. Lim, C.M. Karner, S.Y. Lee, J. Heisig, C. Wiese, K. Surendran, R. Kopan, M. Gessler, F. Long, Physiological Notch Signaling Maintains Bone Homeostasis via RBPjk and Hey Upstream of NFATc1, PLOS Genet. 8 (2012) e1002577. [CrossRef]

- K. Inoue, X. Hu, B. Zhao, Regulatory network mediated by RBP-J/NFATc1-miR182 controls inflammatory bone resorption, FASEB J. 34 (2020) 2392. [CrossRef]

- S. Zanotti, E. Canalis, Notch regulation of bone development and remodeling and related skeletal disorders., Calcif. Tissue Int. 90 (2012) 69–75. [CrossRef]

- L. Dailey, D. Ambrosetti, A. Mansukhani, C. Basilico, Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling., Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 (2005) 233–47. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Lemmon, J. Schlessinger, Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases., Cell 141 (2010) 1117–34. [CrossRef]

- X. Du, Y. Xie, C.J. Xian, L. Chen, Role of FGFs/FGFRs in skeletal development and bone regeneration., J. Cell. Physiol. 227 (2012) 3731–43. [CrossRef]

- D.M. Ornitz, P.J. Marie, Fibroblast growth factor signaling in skeletal development and disease, Genes Dev. 29 (2015) 1463–1486. [CrossRef]

- A. Duenser, P. Singh, L.A. Lecaudey, C. Sturmbauer, R.C. Albertson, W. Gessl, E.P. Ahi, Conserved Molecular Players Involved in Human Nose Morphogenesis Underlie Evolution of the Exaggerated Snout Phenotype in Cichlids, Genome Biol. Evol. 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- L.A. Lecaudey, P. Singh, C. Sturmbauer, A. Duenser, W. Gessl, E.P. Ahi, Transcriptomics unravels molecular players shaping dorsal lip hypertrophy in the vacuum cleaner cichlid, Gnathochromis permaxillaris, BMC Genomics 22 (2021) 506. [CrossRef]

- L.A. Lecaudey, C. Sturmbauer, P. Singh, E.P. Ahi, Molecular mechanisms underlying nuchal hump formation in dolphin cichlid, Cyrtocara moorii, Sci. Rep. (2019). [CrossRef]

- J.E. Lazarus, A. Hegde, A.C. Andrade, O. Nilsson, J. Baron, Fibroblast growth factor expression in the postnatal growth plate, Bone 40 (2007) 577–586. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, A. Zinkle, L. Chen, M. Mohammadi, Fibroblast growth factor signalling in osteoarthritis and cartilage repair, Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020 1610 16 (2020) 547–564. [CrossRef]

- O. Häärä, E. Harjunmaa, P.H. Lindfors, S.H. Huh, I. Fliniaux, T. Åberg, J. Jernvall, D.M. Ornitz, M.L. Mikkola, I. Thesleff, Ectodysplasin regulates activator-inhibitor balance in murine tooth development through fgf20 signaling, Dev. 139 (2012) 3189–3199. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Huh, K. Närhi, P.H. Lindfors, O. Häärä, L. Yang, D.M. Ornitz, M.L. Mikkola, Fgf20 governs formation of primary and secondary dermal condensations in developing hair follicles, Genes Dev. 27 (2013) 450–458. [CrossRef]

- D. Dhouailly, The avian ectodermal default competence to make feathers, Dev. Biol. 508 (2024) 64–76. [CrossRef]

- M. Iwasaki, J. Kuroda, K. Kawakami, H. Wada, Epidermal regulation of bone morphogenesis through the development and regeneration of osteoblasts in the zebrafish scale, Dev. Biol. 437 (2018) 105–119. [CrossRef]

- A. Suzuki, G. Sugiyama, Y. Ohyama, W. Kumamaru, T. Yamada, Y. Mori, Regulation of NF-kB Signalling Through the PR55β-RelA Interaction in Osteoblasts, In Vivo (Brooklyn). 34 (2020) 601. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, J. Xie, J. Wei, S. Xu, D. Zhang, X. Zhou, Fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) up-regulates gelatinase expression in chondrocytes through nuclear factor-κB p65, J. Bone Miner. Metab. 41 (2023) 17–28. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Bikle, C. Tahimic, W. Chang, Y. Wang, A. Philippou, E.R. Barton, Role of IGF-I signaling in muscle bone interactions, Bone 80 (2015) 79–88. [CrossRef]

- R.G. Maki, Small is beautiful: insulin-like growth factors and their role in growth, development, and cancer., J. Clin. Oncol. 28 (2010) 4985–95. [CrossRef]

- A. Esposito, M. Klüppel, B.M. Wilson, S.R.K. Meka, A. Spagnoli, CXCR4 mediates the effects of IGF-1R signaling in rodent bone homeostasis and fracture repair, Bone 166 (2023) 116600. [CrossRef]

- M.H.C. Sheng, X.D. Zhou, L.F. Bonewald, D.J. Baylink, K.H.W. Lau, Disruption of the insulin-like growth factor-1 gene in osteocytes impairs developmental bone growth in mice, Bone 52 (2013) 133–144. [CrossRef]

- K. Fulzele, T.L. Clemens, Novel functions for insulin in bone, Bone 50 (2012) 452–456. [CrossRef]

- X. Ruan, X. Jin, F. Sun, J. Pi, Y. Jinghu, X. Lin, N. Zhang, G. Chen, IGF signaling pathway in bone and cartilage development, homeostasis, and disease, FASEB J. 38 (2024) e70031. [CrossRef]

- B. Hammerschmidt, T. Schlake, Localization of Shh expression by Wnt and Eda affects axial polarity and shape of hairs, Dev. Biol. 305 (2007) 246–261. [CrossRef]

- M.D. Zhang, J. Zheng, S. Wu, H. Chen, L. Xiang, Dynamic expression of IGFBP3 modulate dual actions of mineralization micro-environment during tooth development via Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway, Biol. Direct 18 (2023) 1–16. [CrossRef]

- F. De Luca, Regulatory role of NF-κB in growth plate chondrogenesis and its functional interaction with Growth Hormone, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 514 (2020) 110916. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Hossain, A. Adithan, M.J. Alam, S.R. Kopalli, B. Kim, C.W. Kang, K.C. Hwang, J.H. Kim, IGF-1 Facilitates Cartilage Reconstruction by Regulating PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and NF-kB Signaling in Rabbit Osteoarthritis, J. Inflamm. Res. 14 (2021) 3555. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, D.D. Bikle, W. Chang, Autocrine and Paracrine Actions of IGF-I Signaling in Skeletal Development, Bone Res. 2013 11 1 (2013) 249–259. [CrossRef]

- M. Anghelina, D. Sjostrom, P. Perera, J. Nam, T. Knobloch, S. Agarwal, Regulation of biomechanical signals by NF-κB transcription factors in chondrocytes, Biorheology 45 (2008) 245. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, J. Wang, Y. Zhang, G. Zhu, Y.P. Li, J. Ping, W. Chen, Bone resorption deficiency affects tooth root development in RANKL mutant mice due to attenuated IGF-1 signaling in radicular odontoblasts, Bone 114 (2018) 161–171. [CrossRef]

- M. Qi, E.A. Elion, MAP kinase pathways., J. Cell Sci. 118 (2005) 3569–72. [CrossRef]

- B.E. Bobick, W.M. Kulyk, Regulation of cartilage formation and maturation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 84 (2008) 131–154. [CrossRef]

- M.B. Greenblatt, J.H. Shim, L.H. Glimcher, Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in osteoblasts, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 29 (2013) 63–79. [CrossRef]

- T.W. Tai, F.C. Su, C.Y. Chen, I.M. Jou, C.F. Lin, Activation of p38 MAPK-regulated Bcl-xL signaling increases survival against zoledronic acid-induced apoptosis in osteoclast precursors, Bone 67 (2014) 166–174. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Papachristou, P. Pirttiniemi, T. Kantomaa, A.G. Papavassiliou, E.K. Basdra, JNK/ERK-AP-1/Runx2 induction “paves the way” to cartilage load-ignited chondroblastic differentiation., Histochem. Cell Biol. 124 (2005) 215–23. [CrossRef]

- M.B. Greenblatt, J.M. Kim, H. Oh, K.H. Park, M.K. Choo, Y. Sano, C.E. Tye, Z. Skobe, R.J. Davis, J.M. Park, M. Bei, L.H. Glimcher, J.H. Shim, P38α MAPK is required for tooth morphogenesis and enamel secretion, J. Biol. Chem. 290 (2015) 284–295. [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, M.T. Eby, S. Sinha, A. Jasmin, P.M. Chaudhary, The Ectodermal Dysplasia Receptor Activates the Nuclear Factor-κB, JNK, and Cell Death Pathways and Binds to Ectodysplasin A, J. Biol. Chem. 276 (2001) 2668–2677. [CrossRef]

- S. Papa, C. Bubici, F. Zazzeroni, C.G. Pham, C. Kuntzen, J.R. Knabb, K. Dean, G. Franzoso, The NF-κB-mediated control of the JNK cascade in the antagonism of programmed cell death in health and disease, Cell Death Differ. 2006 135 13 (2006) 712–729. [CrossRef]

- S. Abbas, J.C. Clohisy, Y. Abu-Amer, Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases mediate PMMA-induction of osteoclasts, J. Orthop. Res. 21 (2003) 1041–1048. [CrossRef]

- M.T. Su, K. Ono, D. Kezuka, S. Miyamoto, Y. Mori, T. Takai, Fibronectin-LILRB4/gp49B interaction negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of RANKL-induced TRAF6/TAK1/NF–kB/MAPK signaling, Int. Immunol. 35 (2023) 135–145. [CrossRef]

- V. Ulivi, P. Giannoni, C. Gentili, R. Cancedda, F. Descalzi, p38/NF-kB-dependent expression of COX-2 during differentiation and inflammatory response of chondrocytes, J. Cell. Biochem. 104 (2008) 1393–1406. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, J.Y. Li, X.Z. Zhang, L. Liu, Z.M. Wan, R.X. Li, Y. Guo, Involvement of p38MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in osteoblasts differentiation in response to mechanical stretch, Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40 (2012) 1884–1894. [CrossRef]

- K. Niederreither, P. Dollé, Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view., Nat. Rev. Genet. 9 (2008) 541–53. [CrossRef]

- M. Pacifici, Retinoid roles and action in skeletal development and growth provide the rationale for an ongoing heterotopic ossification prevention trial, Bone 109 (2018) 267–275. [CrossRef]

- M. Theodosiou, V. Laudet, M. Schubert, From carrot to clinic: an overview of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67 (2010) 1423–1445. [CrossRef]

- E. Van Beek, C. Löwik, M. Karperien, S. Papapoulos, Independent pathways in the modulation of osteoclastic resorption by intermediates of the mevalonate biosynthetic pathway: The role of the retinoic acid receptor, Bone 38 (2006) 167–171. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Ashique, S.R. May, M.A. Kane, A.E. Folias, K. Phamluong, Y. Choe, J.L. Napoli, A.S. Peterson, Morphological defects in a novel Rdh10 mutant that has reduced retinoic acid biosynthesis and signaling., Genesis 50 (2012) 415–23. [CrossRef]

- T. Yu, M. Chen, J. Wen, J. Liu, K. Li, L. Jin, J. Yue, Z. Yang, J. Xi, The effects of all-trans retinoic acid on prednisolone-induced osteoporosis in zebrafish larvae, Bone 189 (2024) 117261. [CrossRef]

- A. Sadier, W.R. Jackman, V. Laudet, Y. Gibert, The Vertebrate Tooth Row: Is It Initiated by a Single Organizing Tooth?, BioEssays 42 (2020) 1900229. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim, R. Chen, M. Sheu, N. Kim, S. Kim, N. Islam, E.M. Wier, G. Wang, A. Li, A. Park, W. Son, B. Evans, V. Yu, V.P. Prizmic, E. Oh, Z. Wang, J. Yu, W. Huang, N.K. Archer, Z. Hu, N. Clemetson, A.M. Nelson, A. Chien, G.A. Okoye, L.S. Miller, G. Ghiaur, S. Kang, J.W. Jones, M.A. Kane, L.A. Garza, Noncoding dsRNA induces retinoic acid synthesis to stimulate hair follicle regeneration via TLR3, Nat. Commun. 2019 101 10 (2019) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- T. Shimo, H. Takebe, T. Okui, Y. Kunisada, S. Ibaragi, K. Obata, N. Kurio, K. Shamsoon, S. Fujii, A. Hosoya, K. Irie, A. Sasaki, M. Iwamoto, Expression and Role of IL-1β Signaling in Chondrocytes Associated with Retinoid Signaling during Fracture Healing, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 21, Page 2365 21 (2020) 2365. [CrossRef]

- L. Guo, Y. Zhang, H. Liu, Q. Cheng, S. Yang, D. Yang, All-trans retinoic acid inhibits the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells by promoting IL-1β production via NF-κB signaling, Int. Immunopharmacol. 108 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R. Mishra, I. Sehring, M. Cederlund, M. Mulaw, G. Weidinger, NF-κB Signaling Negatively Regulates Osteoblast Dedifferentiation during Zebrafish Bone Regeneration, Dev. Cell 52 (2020) 167-182.e7. [CrossRef]

- P.K. Farmer, X. He, M.L. Schmitz, J. Rubin, M.S. Nanes, Inhibitory effect of NF-κB on 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 and retinoid X receptor function, Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 279 (2000). [CrossRef]

- D.W. Alhamad, H. Bensreti, J. Dorn, W.D. Hill, M.W. Hamrick, M.E. McGee-Lawrence, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-mediated signaling as a critical regulator of skeletal cell biology, J. Mol. Endocrinol. 69 (2022) R109–R124. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Goodale, J.K. La Du, W.H. Bisson, D.B. Janszen, K.M. Waters, R.L. Tanguay, AHR2 Mutant Reveals Functional Diversity of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptors in Zebrafish, PLoS One 7 (2012) e29346. [CrossRef]

- E.P. Ahi, S.S. Steinhäuser, A. Pálsson, S.R. Franzdóttir, S.S. Snorrason, V.H. Maier, Z.O. Jónsson, Differential expression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway associates with craniofacial polymorphism in sympatric Arctic charr, Evodevo 6 (2015) 27. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Souder, D.A. Gorelick, ahr2, But Not ahr1a or ahr1b, Is Required for Craniofacial and Fin Development and TCDD-dependent Cardiotoxicity in Zebrafish, Toxicol. Sci. 170 (2019) 25–44. [CrossRef]

- R. Park, S. Madhavaram, J.D. Ji, The Role of Aryl-Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) in Osteoclast Differentiation and Function, Cells 2020, Vol. 9, Page 2294 9 (2020) 2294. [CrossRef]

- N. Chen, Q. Shan, Y. Qi, W. Liu, X. Tan, J. Gu, Transcriptome analysis in normal human liver cells exposed to 2, 3, 3′, 4, 4′, 5 - Hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 156), Chemosphere 239 (2020) 124747. [CrossRef]

- C.F.A. Vogel, E.M. Khan, P.S.C. Leung, M.E. Gershwin, W.L.W. Chang, D. Wu, T. Haarmann-Stemmann, A. Hoffmann, M.S. Denison, Cross-talk between Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and the Inflammatory Response: A ROLE FOR NUCLEAR FACTOR-κB *, J. Biol. Chem. 289 (2014) 1866–1875. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ye, X. Xi, D. Fan, X. Cao, Q. Wang, X. Wang, M. Zhang, B. Wang, Q. Tao, C. Xiao, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in bone homeostasis, Biomed. Pharmacother. 146 (2022) 112547. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhuang, X. Ren, F. Jiang, P. Zhou, Indole-3-propionic acid alleviates chondrocytes inflammation and osteoarthritis via the AhR/NF-κB axis, Mol. Med. 29 (2023) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- G.P. Chrousos, T. Kino, Glucocorticoid Signaling in the Cell, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1179 (2009) 153–166. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Cooper, M.J. Seibel, H. Zhou, Glucocorticoids, bone and energy metabolism, Bone 82 (2016) 64–68. [CrossRef]

- W. Yao, W. Dai, J.X. Jiang, N.E. Lane, Glucocorticoids and osteocyte autophagy, Bone 54 (2013) 279–284. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Galliher-Beckley, J.G. Williams, J.A. Cidlowski, Ligand-independent phosphorylation of the glucocorticoid receptor integrates cellular stress pathways with nuclear receptor signaling., Mol. Cell. Biol. 31 (2011) 4663–75. [CrossRef]

- S. Pikulkaew, F. Benato, A. Celeghin, C. Zucal, T. Skobo, L. Colombo, L. Dalla Valle, The knockdown of maternal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA alters embryo development in zebrafish., Dev. Dyn. 240 (2011) 874–89. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Hillegass, C.M. Villano, K.R. Cooper, L.A. White, Glucocorticoids Alter Craniofacial Development and Increase Expression and Activity of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio), Toxicol. Sci. 102 (2008) 413–424. [CrossRef]

- E.P. Ahi, K.H. Kapralova, A. Pálsson, V.H. Maier, J. Gudbrandsson, S.S. Snorrason, Z.O. Jónsson, S.R. Franzdóttir, Transcriptional dynamics of a conserved gene expression network associated with craniofacial divergence in Arctic charr, Evodevo 5 (2014). [CrossRef]

- G. Adami, D. Gatti, M. Rossini, A. Giollo, M. Gatti, F. Bertoldo, E. Bertoldo, A.S. Mudano, K.G. Saag, O. Viapiana, A. Fassio, Risk of fracture in women with glucocorticoid requiring diseases is independent from glucocorticoid use: An analysis on a nation-wide database, Bone 179 (2024) 116958. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Robinson, E.M. Dennison, C. Cooper, T.P. van Staa, W.G. Dixon, A review of the methods used to define glucocorticoid exposure and risk attribution when investigating the risk of fracture in a rheumatoid arthritis population, Bone 90 (2016) 107–115. [CrossRef]

- K. Harrison, L. Loundagin, B. Hiebert, A. Panahifar, N. Zhu, D. Marchiori, T. Arnason, K. Swekla, P. Pivonka, D. Cooper, Glucocorticoids disrupt longitudinal advance of cortical bone basic multicellular units in the rabbit distal tibia, Bone 187 (2024) 117171. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakamura, M.R. Schneider, R. Schmidt-Ullrich, R. Paus, Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis, cycling, and/or structure: An update, J. Dermatol. Sci. 69 (2013) 6–29. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Cascallana, A. Bravo, E. Donet, H. Leis, M.F. Lara, J.M. Paramio, J.L. Jorcano, P. Pérez, Ectoderm-Targeted Overexpression of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Induces Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia, Endocrinology 146 (2005) 2629–2638. [CrossRef]

- A. Rauch, S. Seitz, U. Baschant, A.F. Schilling, A. Illing, B. Stride, M. Kirilov, V. Mandic, A. Takacz, R. Schmidt-Ullrich, S. Ostermay, T. Schinke, R. Spanbroek, M.M. Zaiss, P.E. Angel, U.H. Lerner, J.P. David, H.M. Reichardt, M. Amling, G. Schütz, J.P. Tuckermann, Glucocorticoids suppress bone formation by attenuating osteoblast differentiation via the monomeric glucocorticoid receptor, Cell Metab. 11 (2010) 517–531. [CrossRef]

- B. Frenkel, W. White, J. Tuckermann, Glucocorticoid-Induced osteoporosis, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 872 (2015) 179–215. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Roman-Blas, S.A. Jimenez, NF-κB as a potential therapeutic target in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14 (2006) 839–848. [CrossRef]

- A.B. Khalid, S.A. Krum, Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in bone, Bone 87 (2016) 130–135. [CrossRef]

- V. Shi, E.F. Morgan, Estrogen and estrogen receptors mediate the mechanobiology of bone disease and repair, Bone 188 (2024) 117220. [CrossRef]

- F.A. Syed, U. IL Mödder, D.G. Fraser, T.C. Spelsberg, C.J. Rosen, A. Krust, P. Chambon, J.L. Jameson, S. Khosla, Skeletal Effects of Estrogen Are Mediated by Opposing Actions of Classical and Nonclassical Estrogen Receptor Pathways, J. Bone Miner. Res. 20 (2005) 1992–2001. [CrossRef]

- Y. Feng, H. Wang, S. Xu, J. Huang, Q. Pei, Z. Wang, The detection of Gper1 as an important gene promoting jawbone regeneration in the context of estrogen deficiency, Bone 180 (2024) 116990. [CrossRef]

- L.B. Tankó, B.-C. Søndergaard, S. Oestergaard, M.A. Karsdal, C. Christiansen, An update review of cellular mechanisms conferring the indirect and direct effects of estrogen on articular cartilage., Climacteric 11 (2008) 4–16. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Metzger, P. Olayooye, L.Y. Tak, O. Culpepper, A.N. LaPlant, P. Jalaie, P.M. Andoh, W. Bandara, O.N. Reul, A.A. Tomaschke, R.K. Surowiec, Estrogen deficiency induces changes in bone matrix bound water that do not closely correspond with bone turnover, Bone 186 (2024) 117173. [CrossRef]

- K.E. Warner, J.J. Jenkins, Effects of 17alpha-ethinylestradiol and bisphenol A on vertebral development in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas)., Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 26 (2007) 732–7. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17447558 (accessed on 14 September 2015).

- E. Pashay Ahi, B.S. Walker, C.S. Lassiter, Z.O. Jónsson, Investigation of the effects of estrogen on skeletal gene expression during zebrafish larval head development, PeerJ 4 (2016) e1878. [CrossRef]

- P. Singh, E.P. Ahi, C. Sturmbauer, Gene coexpression networks reveal molecular interactions underlying cichlid jaw modularity, BMC Ecol. Evol. 21 (2021) 1–17. [CrossRef]

- S. Fushimi, N. Wada, T. Nohno, M. Tomita, K. Saijoh, S. Sunami, H. Katsuyama, 17beta-Estradiol inhibits chondrogenesis in the skull development of zebrafish embryos., Aquat. Toxicol. 95 (2009) 292–8. [CrossRef]

- E. Pashay Ahi, B.S. Walker, C.S. Lassiter, Z.O. Jónsson, Investigation of the effects of estrogen on skeletal gene expression during zebrafish larval head development., PeerJ 4 (2016) e1878. [CrossRef]

- A. Tingaud-Sequeira, J. Forgue, M. André, P.J. Babin, Epidermal transient down-regulation of retinol-binding protein 4 and mirror expression of apolipoprotein Eb and estrogen receptor 2a during zebrafish fin and scale development, Dev. Dyn. 235 (2006) 3071–3079. [CrossRef]

- S. Paruthiyil, A. Cvoro, X. Zhao, Z. Wu, Y. Sui, R.E. Staub, S. Baggett, C.B. Herber, C. Griffin, M. Tagliaferri, H.A. Harris, I. Cohen, L.F. Bjeldanes, T.P. Speed, F. Schaufele, D.C. Leitman, Drug and Cell Type-Specific Regulation of Genes with Different Classes of Estrogen Receptor β-Selective Agonists, PLoS One 4 (2009) e6271. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Quaedackers, C.E. Van Den Brink, S. Wissink, R.H.M.M. Schreurs, J.Å. Gustafsson, P.T. Van Der Saag, B. Van Der Burg, 4-Hydroxytamoxifen Trans-Represses NuclearFactor-κB Activity in Human Osteoblastic U2-OS Cells through EstrogenReceptor (ER)α, and Not through ERβ, Endocrinology 142 (2001) 1156–1166. [CrossRef]

- M. Martin-Millan, M. Almeida, E. Ambrogini, L. Han, H. Zhao, R.S. Weinstein, R.L. Jilka, C.A. O’Brien, S.C. Manolagas, The Estrogen Receptor-α in Osteoclasts Mediates the Protective Effects of Estrogens on Cancellous But Not Cortical Bone, Mol. Endocrinol. 24 (2010) 323–334. [CrossRef]

- F.C. Liu, C.C. Wang, J.W. Lu, C.H. Lee, S.C. Chen, Y.J. Ho, Y.J. Peng, Chondroprotective Effects of Genistein against Osteoarthritis Induced Joint Inflammation, Nutr. 2019, Vol. 11, Page 1180 11 (2019) 1180. [CrossRef]

- H. Allison, L.M. McNamara, Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by mechanically stimulated osteoblasts is attenuated during estrogen deficiency, Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 317 (2019) C969–C982. [CrossRef]

- L. Penolazzi, M. Zennaro, E. Lambertini, E. Tavanti, E. Torreggiani, R. Gambari, R. Piva, Induction of Estrogen Receptor α Expression with Decoy Oligonucleotide Targeted to NFATc1 Binding Sites in Osteoblasts, Mol. Pharmacol. 71 (2007) 1457–1462. [CrossRef]

- S. Suthon, J. Lin, R.S. Perkins, J.R. Crockarell, G.A. Miranda-Carboni, S.A. Krum, Estrogen receptor alpha and NFATc1 bind to a bone mineral density-associated SNP to repress WNT5B in osteoblasts, Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109 (2022) 97. [CrossRef]

- D. Sitara, A.O. Aliprantis, Transcriptional regulation of bone and joint remodeling by NFAT, Immunol. Rev. 233 (2010) 286–300. [CrossRef]

- H. Zheng, Y. Liu, Y. Deng, Y. Li, S. Liu, Y. Yang, Y. Qiu, B. Li, W. Sheng, J. Liu, C. Peng, W. Wang, H. Yu, Recent advances of NFATc1 in rheumatoid arthritis-related bone destruction: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets, Mol. Med. 2024 301 30 (2024) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- H. min Kim, L. He, S. Lee, C. Park, D.H. Kim, H.J. Han, J. Han, J. Hwang, H. Cha-Molstad, K.H. Lee, S.K. Ko, J.H. Jang, I.J. Ryoo, J. Blenis, H.G. Lee, J.S. Ahn, Y.T. Kwon, N.K. Soung, B.Y. Kim, Inhibition of osteoclasts differentiation by CDC2-induced NFATc1 phosphorylation, Bone 131 (2020) 115153. [CrossRef]

- R. Ren, J. Guo, Y. Chen, Y. Zhang, L. Chen, W. Xiong, The role of Ca2+ /Calcineurin/NFAT signalling pathway in osteoblastogenesis, Cell Prolif. 54 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J.H. Kim, N. Kim, Regulation of NFATc1 in Osteoclast Differentiation, J. Bone Metab. 21 (2014) 233. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, B.M. Gardner, Q. Lu, M. Rodova, B.G. Woodbury, J.G. Yost, K.F. Roby, D.M. Pinson, O. Tawfik, H.C. Anderson, Transcription factor Nfat1 deficiency causes osteoarthritis through dysfunction of adult articular chondrocytes, J. Pathol. 219 (2009) 163–172. [CrossRef]

- C.M. Park, H.M. Kim, D.H. Kim, H.J. Han, H. Noh, J.H. Jang, S.H. Park, H.J. Chae, S.W. Chae, E.K. Ryu, S. Lee, K. Liu, H. Liu, J.S. Ahn, Y.O. Kim, B.Y. Kim, N.K. Soung, Ginsenoside Re Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation in Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages and Zebrafish Scale Model, Mol. Cells 39 (2016) 855. [CrossRef]

- M. Asagiri, K. Sato, T. Usami, S. Ochi, H. Nishina, H. Yoshida, I. Morita, E.F. Wagner, T.W. Mak, E. Serfling, H. Takayanagi, Autoamplification of NFATc1 expression determines its essential role in bone homeostasis, J. Exp. Med. 202 (2005) 1261. [CrossRef]

- Y. Abu-Amer, NF-κB signaling and bone resorption, Osteoporos. Int. 2013 249 24 (2013) 2377–2386. [CrossRef]

- M. Noordijk, J.L. Davideau, S. Eap, O. Huck, F. Fioretti, J.F. Stoltz, W. Bacon, N. Benkirane-Jessel, F. Clauss, Bone defects and future regenerative nanomedicine approach using stem cells in the mutant Tabby mouse model, Biomed. Mater. Eng. 25 (2015) S111–S119. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, K. Chen, Q. Yu, Y. Li, S. Tong, R. Xu, R. Hu, Y. Zhang, W. Xu, Suppression of NFATc1 through NF-kB/PI3K signaling pathway by Oleandrin to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption, Eng. Regen. (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, R. Tang, J. Yi, Y. Chen, X. Li, T. Yu, J. Fei, Diallyl disulfide alleviates inflammatory osteolysis by suppressing osteoclastogenesis via NF-κB–NFATc1 signal pathway, FASEB J. 33 (2019) 7261. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Gensure, T.J. Gardella, H. Jüppner, Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide, and their receptors, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328 (2005) 666–678. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, A.R. Nasiri, A.E. Broadus, S.M. Tommasini, Periosteal PTHrP Regulates Cortical Bone Remodeling During Fracture Healing, Bone 81 (2015) 104–111. [CrossRef]

- T. John Martin, Parathyroid hormone-related protein, its regulation of cartilage and bone development, and role in treating bone diseases, Physiol. Rev. 96 (2016) 831–871. [CrossRef]

- M. Voutilainen, P.H. Lindfors, S. Lefebvre, L. Ahtiainen, I. Fliniaux, E. Rysti, M. Murtoniemi, P. Schneider, R. Schmidt-Ullrich, M.L. Mikkola, Ectodysplasin regulates hormone-independent mammary ductal morphogenesis via NF-κB, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (2012) 5744–5749. [CrossRef]

- P. Liu, Y. Li, W. Wang, Y. Bai, H. Jia, Z. Yuan, Z. Yang, Role and mechanisms of the NF-ĸB signaling pathway in various developmental processes, Biomed. Pharmacother. 153 (2022) 113513. [CrossRef]

- P. Rao, J. jing, Y. Fan, C. Zhou, Spatiotemporal cellular dynamics and molecular regulation of tooth root ontogeny, Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023 151 15 (2023) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- C. Matta, R. Zakany, Calcium signalling in chondrogenesis: implications for cartilage repair., Front. Biosci. (Schol. Ed). 5 (2013) 305–24. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23277053 (accessed on 8 September 2015).

- M. Zayzafoon, Calcium/calmodulin signaling controls osteoblast growth and differentiation, J. Cell. Biochem. 97 (2006) 56–70. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Seales, K.J. Micoli, J.M. McDonald, Calmodulin is a critical regulator of osteoclastic differentiation, function, and survival, J. Cell. Biochem. 97 (2006) 45–55. [CrossRef]

- A. Abzhanov, W.P. Kuo, C. Hartmann, B.R. Grant, P.R. Grant, C.J. Tabin, The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin’s finches., Nature 442 (2006) 563–7. [CrossRef]

- K.J. Parsons, R.C. Albertson, Roles for Bmp4 and CaM1 in Shaping the Jaw: Evo-Devo and Beyond, Annu. Rev. Genet. 43 (2009) 369–388. [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, The role of growth factors in tooth development, Int. Rev. Cytol. 217 (2002) 93–135. [CrossRef]

- H. Park, K. Hosomichi, Y. Il Kim, Y. Hikita, A. Tajima, T. Yamaguchi, Comprehensive Genetic Exploration of Fused Teeth by Whole Exome Sequencing, Appl. Sci. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 11899 12 (2022) 11899. [CrossRef]

- F. Qu, Z. Zhao, B. Yuan, W. Qi, C. Li, X. Shen, C. Liu, H. Li, G. Zhao, J. Wang, Q. Guo, Y. Liu, CaMKII plays a part in the chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8 (2015) 5981. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4503202/ (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Y.-H. Choi, E.-J. Ann, J.-H. Yoon, J.-S. Mo, M.-Y. Kim, H.-S. Park, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (CaMKIV) enhances osteoclast differentiation via the up-regulation of Notch1 protein stability, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 1833 (2013) 69–79. [CrossRef]

- A.-K. Khimji, D.C. Rockey, Endothelin--biology and disease., Cell. Signal. 22 (2010) 1615–25. [CrossRef]

- J. Kristianto, M.G. Johnson, R. Afzal, R.D. Blank, Endothelin Signaling in Bone, Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 46 (2016) 51. [CrossRef]

- A. Sehgal, T. Behl, S. Singh, N. Sharma, M. Albratty, H.A. Alhazmi, A.M. Meraya, L. Aleya, A. Sharma, S. Bungau, Exploring the pivotal role of endothelin in rheumatoid arthritis, Inflammopharmacology 30 (2022) 1555–1567. [CrossRef]

- D. Esibizione, C.-Y. Cui, D. Schlessinger, Candidate EDA targets revealed by expression profiling of primary keratinocytes from Tabby mutant mice, Gene 427 (2008) 42–46. [CrossRef]

- M.T. Cobourne, P.T. Sharpe, Tooth and jaw: molecular mechanisms of patterning in the first branchial arch, Arch. Oral Biol. 48 (2003) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- L. Barske, P. Rataud, K. Behizad, L. Del Rio, S.G. Cox, J.G. Crump, Essential role of Nr2f nuclear receptors in patterning the vertebrate upper jaw, Dev. Cell 44 (2018) 337. [CrossRef]

- J. Che, X. Yang, Z. Jin, C. Xu, Nrf2: A promising therapeutic target in bone-related diseases, Biomed. Pharmacother. 168 (2023) 115748. [CrossRef]

- P. Vogel, J. Liu, K.A. Platt, R.W. Read, M. Thiel, R.B. Vance, R. Brommage, Malformation of Incisor Teeth in Grem2-/- Mice, Vet. Pathol. 52 (2015) 224–229. [CrossRef]

- P. Ducy, G. Karsenty, The two faces of serotonin in bone biology, J. Cell Biol. 191 (2010) 7–13. [CrossRef]

- A. Hori, T. Nishida, S. Takashiba, S. Kubota, M. Takigawa, Regulatory mechanism of CCN2 production by serotonin (5-HT) via 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors in chondrocytes, PLoS One 12 (2017) e0188014. [CrossRef]

- J.R.D. Moiseiwitsch, The role of serotonin and neurotransmitters during craniofacial development, Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 11 (2000) 230–239. [CrossRef]

- T.L. Brown, E.C. Horton, E.W. Craig, C.E.A. Goo, E.C. Black, M.N. Hewitt, N.G. Yee, E.T. Fan, D.W. Raible, J.P. Rasmussen, Dermal appendage-dependent patterning of zebrafish atoh1a+ Merkel cells, Elife 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Chabbi-Achengli, A.E. Coudert, J. Callebert, V. Geoffroy, F. Côté, C. Collet, M.C. De Vernejoul, Decreased osteoclastogenesis in serotonin-deficient mice, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (2012) 2567–2572. [CrossRef]

- E.M. Tsapakis, Z. Gamie, G.T. Tran, S. Adshead, A. Lampard, A. Mantalaris, E. Tsiridis, The adverse skeletal effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, Eur. Psychiatry 27 (2012) 156–169. [CrossRef]

- C. Xue, G. Li, Q. Zheng, X. Gu, Q. Shi, Y. Su, Q. Chu, X. Yuan, Z. Bao, J. Lu, L. Li, Tryptophan metabolism in health and disease, Cell Metab. 35 (2023) 1304–1326. [CrossRef]

- S. Murab, S. Chameettachal, M. Bhattacharjee, S. Das, D.L. Kaplan, S. Ghosh, Matrix-Embedded Cytokines to Simulate Osteoarthritis-Like Cartilage Microenvironments, (2013) 1733–1753. Available online: https://Home.Liebertpub.Com/Tea 19. [CrossRef]

- D. Docheva, C. Popov, P. Alberton, A. Aszodi, Integrin signaling in skeletal development and function, Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 102 (2014) 13–36. [CrossRef]

- D. Kronenberg, M. Brand, J. Everding, L. Wendler, E. Kieselhorst, M. Timmen, M.D. Hülskamp, R. Stange, Integrin α2β1 deficiency enhances osteogenesis via BMP-2 signaling for accelerated fracture repair, Bone 190 (2025) 117318. [CrossRef]

- E.K. Song, T.J. Park, Integrin signaling in cartilage development, Animal Cells Syst. (Seoul). 18 (2014) 365–371. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Mikkola, J. Pispa, M. Pekkanen, L. Paulin, P. Nieminen, J. Kere, I. Thesleff, Ectodysplasin, a protein required for epithelial morphogenesis, is a novel TNF homologue and promotes cell-matrix adhesion, Mech. Dev. 88 (1999) 133–146. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Cui, M. Durmowicz, T.S. Tanaka, A.J. Hartung, T. Tezuka, K. Hashimoto, M.S.H. Ko, A.K. Srivastava, D. Schlessinger, EDA targets revealed by skin gene expression profiles of wild-type, Tabby and Tabby EDA-A1 transgenic mice, Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 (2002) 1763–1773. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Y. Jia, X. Huang, D. Zhu, H. Liu, W. Wang, Transcriptome profiling towards understanding of the morphogenesis in the scale development of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala), Genomics 113 (2021) 983–991. [CrossRef]

- R. Li, Y. Shi, S. Zhao, T. Shi, G. Zhang, NF-κB signaling and integrin-β1 inhibition attenuates osteosarcoma metastasis via increased cell apoptosis, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 123 (2019) 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- S.R.L. Young, R. Gerard-O’Riley, M. Harrington, F.M. Pavalko, Activation of NF-κB by fluid shear stress, but not TNF-α, requires focal adhesion kinase in osteoblasts, Bone 47 (2010) 74–82. [CrossRef]

- C.C. Teixeira, H. Ischiropoulos, P.S. Leboy, S.L. Adams, I.M. Shapiro, Nitric oxide–nitric oxide synthase regulates key maturational events during chondrocyte terminal differentiation, Bone 37 (2005) 37–45. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Wimalawansa, Nitric oxide and bone, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1192 (2010) 391–403. [CrossRef]

- J. Klein-Nulend, R.F.M. Van Oers, A.D. Bakker, R.G. Bacabac, Nitric oxide signaling in mechanical adaptation of bone, Osteoporos. Int. 25 (2014) 1427–1437. [CrossRef]

- C.Y. Tsai, F.C.H. Li, C.H.Y. Wu, A.Y.W. Chang, S.H.H. Chan, Sumoylation of IkB attenuates NF-kB-induced nitrosative stress at rostral ventrolateral medulla and cardiovascular depression in experimental brain death, J. Biomed. Sci. 23 (2016) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- M. Sisto, D. Ribatti, S. Lisi, Understanding the Complexity of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Remarkable Progress in Elucidating NF-κB Mechanisms, J. Clin. Med. 2020, Vol. 9, Page 2821 9 (2020) 2821. [CrossRef]

- M. Ostojic, V. Soljic, K. Vukojevic, T. Dapic, Immunohistochemical characterization of early and advanced knee osteoarthritis by NF-κB and iNOS expression, J. Orthop. Res. 35 (2017) 1990–1997. [CrossRef]

- T. Fang, X. Zhou, M. Jin, J. Nie, Xi.I. Li, Molecular mechanisms of mechanical load-induced osteoarthritis, Int. Orthop. 45 (2021) 1125–1136. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, J. Ming, M. Deng, Y. Li, B. Li, J. Li, Y. Ma, Z. Chen, S. Liu, Berberine-mediated up-regulation of surfactant protein D facilitates cartilage repair by modulating immune responses via the inhibition of TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling, Pharmacol. Res. 155 (2020) 104690. [CrossRef]

- V. Veeriah, A. Zanniti, R. Paone, S. Chatterjee, N. Rucci, A. Teti, M. Capulli, Interleukin-1β, lipocalin 2 and nitric oxide synthase 2 are mechano-responsive mediators of mouse and human endothelial cell-osteoblast crosstalk, Sci. Reports 2016 61 6 (2016) 1–14. [CrossRef]

| Pathway | Bone | Cartilage | Tooth | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | Unknown | Unknown | Antagonistic (D, In2) | 20, 24, 42-44 |

| BMP | Synergistic (D, In1) | Unknown | Antagonistic (D, In1) | 19-21, 52-54 |

| Hh | Both (D) | Synergistic (D) | Synergistic (D) | 2, 20-21, 33, 52, 62-65 |

| Wnt | Both (D, In1, In2) | Both (D, In1, In2) | Synergistic (D, In1, In2) | 23, 31, 33, 54, 62, 73-82 |

| Notch | Both (In1, In2) | Antagonistic (In1, In2) | Unknown | 90-97 |

| FGF | Synergistic (D, In2) | Synergistic (D, In2) | Synergistic (D, In2) | 6, 33, 62, 107-112 |

| IGF | Both (In1, In2) | Both (In1, In2) | Both (In1, In2) | 119-125 |

| MAPK | Synergistic (In2) | Synergistic (In2) | Unknown | 131-137 |

| RA | Both (In2) | Both (In2) | Synergistic (In2) | 6, 144-149 |

| Ahr | Both (In2) | Both (In2) | Unknown | 153-158 |

| GR | Antagonistic (In2) | Antagonistic (In2) | Antagonistic (In2) | 169-173 |

| ER | Antagonistic (In1, In2) | Antagonistic (In1, In2) | Unknown | 185-192 |

| NFAT | Both (D, In1, In2) | Both (D, In1, In2) | Synergistic (D, In1, In2) | 17, 201-204 |

| PTH/PTHrP | Synergistic (D, In2) | Synergistic (D, In2) | Synergistic (D, In2) | 23, 208-210 |

| Ca2+/CaM | Both (In1, In2) | Antagonistic (In1, In2) | Unknown | 212, 216-219 |

| Edn/Ednr | Synergistic (D, In2) | Both (D, In2) | Synergistic (D, In2) | 223-227 |

| Serotonin | Both (In1, In2) | Both (In1, In2) | Unknown | 17, 231-235 |

| Integrin | Both (D, In2) | Both (D, In2) | Unknown | 239-243 |

| NO | Synergistic (In2) | Both (In2) | Unknown | 244-252 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).