1. Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic, multifactorial inflammatory disease that affects the supporting structures of the teeth, leading to progressive destruction of the periodontal ligament, alveolar bone loss, and ultimately tooth loss [

1]. It is one of the most prevalent oral diseases worldwide, affecting approximately 20% to 50% of the global population to varying degrees of severity [

2]. The primary etiological factor of periodontitis is the microbial biofilm that forms in the gingival sulcus. However, disease progression is not solely due to the presence of bacteria, but also to the host immune-inflammatory response that eventually leads to tissue damage [

3,

4].

In addition, several systemic and environmental modifiers, including smoking, diabetes, and stress, as well as genetic predisposition, are known to influence susceptibility to periodontal breakdown [

4]. Several studies have pointed toward elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers and the presence of specific cytokine gene polymorphisms as contributing to inter-individual variability in disease risk [

5].

Cyclooxygenase (COX), a critical enzyme in the arachidonic acid pathway, catalyzes the production of prostanoids—primarily prostaglandins (PGs)—which are key mediators of inflammation. COX exists in two isoforms: COX-1, which is constitutively expressed in most tissues, and COX-2, which is inducible and upregulated during inflammatory processes [

6,

7]. COX-2 plays a pivotal role in the biosynthesis of prostaglandin E

2 (PGE

2), which contributes to vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, soft tissue degradation, and bone resorption in periodontal lesions [

8,

9].

Numerous cell types in periodontal tissues—including fibroblasts, osteoblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes, and macrophages—are stimulated by inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and lipopolysaccharide from Gram -negative bacteria to upregulate COX-2 expression [

10,

11]. This results in increased local PGE

2 concentrations, which, in concert with cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), drive the degradation of the extracellular matrix and alveolar bone.

Genetic variations in the COX-2 gene may influence its transcriptional regulation, mRNA stability, or enzymatic function, thereby modulating the intensity of inflammatory responses. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the COX-2 gene, including rs20417 (-765G/C), rs689466 (-1195G/A), and rs5275 (8473T/C), among others [

12]. These polymorphisms have been investigated for their potential roles in periodontitis susceptibility, with varying and often conflicting results across populations and study designs.

To date, no clear consensus has been reached regarding the relationship between COX-2 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis. While individual case–control studies may lack statistical power due to small sample sizes or population heterogeneity, meta-analysis allows for the aggregation of findings across multiple studies to yield more robust and generalizable conclusions. The potential application of COX-2 polymorphisms in personalized periodontal care is of increasing clinical interest. As part of a precision medicine approach, identifying genetic susceptibility markers may enable early diagnosis, risk stratification, and targeted anti-inflammatory interventions. This is particularly relevant for populations with high prevalence of periodontitis or known exposure to environmental modifiers such as smoking. Therefore, the present meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the association between two well-characterized COX-2 polymorphisms-765G/C (rs20417) and -1195G/A (rs689466) and periodontitis, synthesizing available evidence from multiple populations [

13]. Until 2017, periodontal diseases were classified according to the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions, which distinguished between

chronic and

aggressive periodontitis based on clinical, epidemiological, and pathophysiological criteria. The studies included in this meta-analysis were published before the adoption of the revised classification system of 2018, which replaced the chronic/aggressive distinction with a

staging and grading framework [

21,

22]. Therefore, the present review refers to periodontal diagnoses as originally reported by the authors, in line with the

1999 classification, to preserve consistency and avoid retrospective misclassification and the term

periodontitis is used throughout the review to reflect the terminology employed in the original publications.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. A detailed protocol was pre-established to ensure transparency and methodological consistency across all stages, from literature search and study selection to data extraction, quality appraisal, and statistical synthesis. The protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number:CRD420251008939) and is accessible at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251008939.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility was defined using the PICOS framework. The population included individuals diagnosed with periodontitis according to recognized diagnostic criteria, including the 2017 AAP/EFP classification system or earlier diagnostic frameworks. The exposure of interest was the presence of COX-2 gene polymorphisms—namely -1195 G/A, -765 G/C, and 8473 T/C—which have been implicated as potential genetic susceptibility factors. Studies were required to include a comparison group of periodontally healthy individuals without clinical attachment loss, pocket depth greater than 3 mm, or radiographic bone loss. The primary outcome was the association between these polymorphisms and periodontitis, expressed through genotypic distributions, odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values.

Only observational studies with case-control or cohort design were considered eligible. Exclusion criteria included studies that did not report genetic data, lacked a healthy control group, or did not examine at least one of the three target polymorphisms. Non-human studies, in vitro research, review articles, editorials, and conference abstracts were excluded. Additionally, studies with fewer than 50 participants per group were not included unless they contributed to a larger pooled analysis. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) compliance in control groups was assessed as a quality criterion; studies deviating from HWE were excluded in sensitivity analyses.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed across five major electronic databases: PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. To minimize the risk of publication bias and identify relevant gray literature, supplementary searches were conducted via Google Scholar. Furthermore, the reference lists of all included articles were manually screened to retrieve any additional eligible studies. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords related to COX-2 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis, using Boolean operators (AND, OR) for logical structuring. No time restrictions were imposed on publication date, and only full-text studies published in English were included.

2.3. Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (V.S and I.F) screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles for relevance. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were then examined against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer (D.S.) when necessary. The entire selection process was documented using a PRISMA flow diagram, which detailed the number of records identified, screened, excluded, and ultimately included in the final analysis.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted independently by the two reviewers using a standardized and piloted data collection form. The following variables were recorded: authorship, year of publication, country of origin, participant ethnicity, age, gender, smoking status, genotype and allele frequencies for each COX-2 polymorphism, statistical measures (including ORs, 95% CIs, and p-values), HWE status in the control group, and whether adjustments for confounding factors such as smoking or diabetes had been made. Discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved through joint review and discussion.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which evaluates selection of study groups, comparability of cases and controls, and ascertainment of exposure. Studies scoring seven or more were deemed high quality, while those scoring six or below were categorized as lower quality and included in sensitivity analyses to assess their potential influence on overall results.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative synthesis was conducted using Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) and STATA software. The strength of association between COX-2 polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis was estimated using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were performed under multiple genetic models, including allelic (e.g., G versus A for -1195 G/A), dominant (e.g., GG + GA versus AA), and recessive (e.g., GG versus GA + AA) models. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values below 25% considered low, between 25% and 50% moderate, and above 50% substantial. Cochran’s Q test was also applied to evaluate the statistical significance of heterogeneity. Depending on the degree of heterogeneity, either a fixed-effects or random-effects model was used, with the latter being preferred in the presence of high heterogeneity.

2.7. Assessment of Publication Bias

To evaluate the risk of publication bias, funnel plots were generated for visual inspection of asymmetry, and Egger’s regression test was applied to detect small-study effects. In cases where evidence of bias was detected, the trim-and-fill method was used to estimate the number of potentially missing studies and adjust the meta-analytic results accordingly.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

As this review relied exclusively on secondary analysis of data extracted from previously published studies, no ethical approval was required. Nevertheless, all procedures adhered to ethical principles relevant to systematic reviews, including accurate reporting, transparency, and data synthesis and interpretation integrity.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

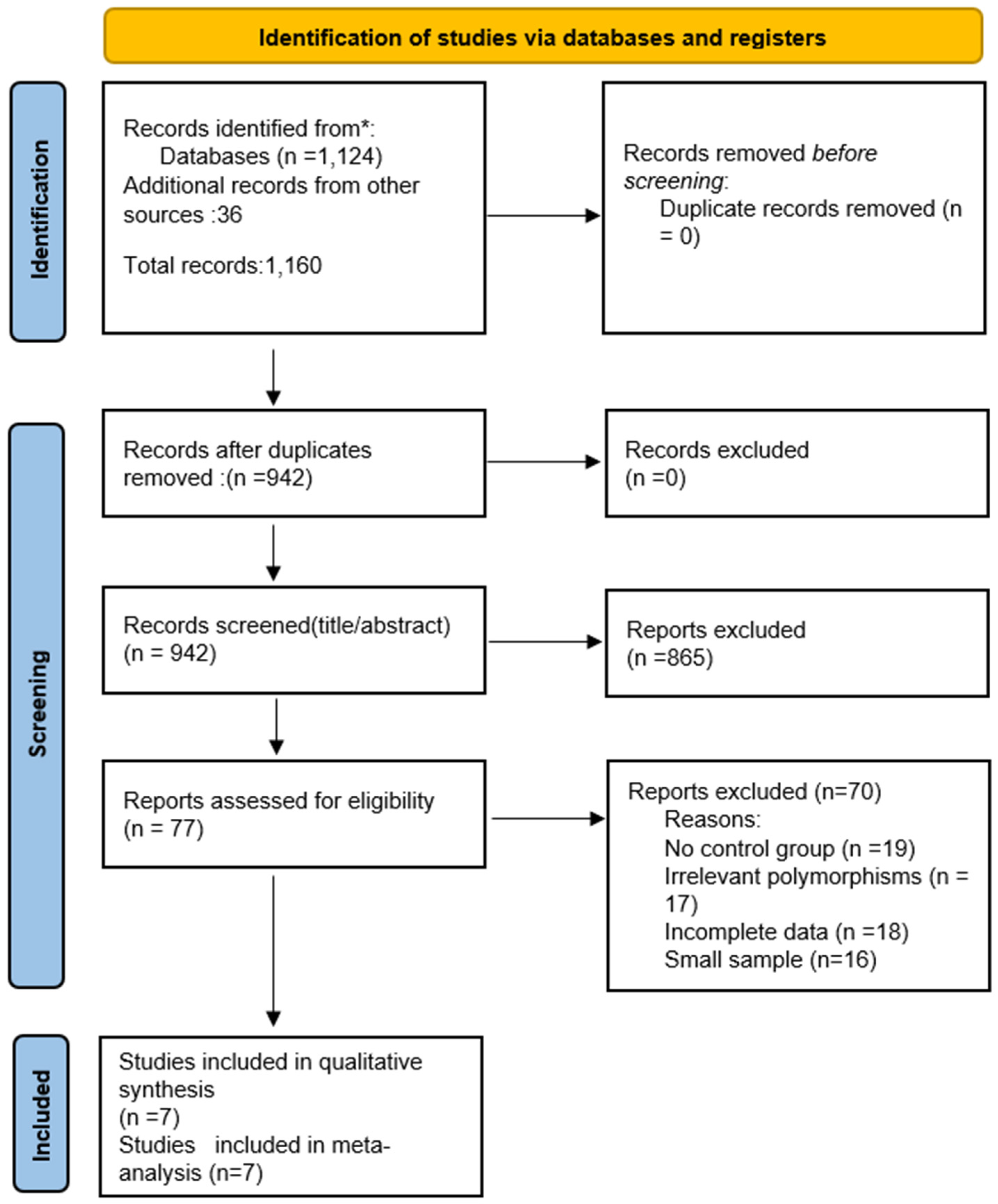

The initial search strategy identified a total of 1,124 records across five electronic databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. An additional 36 records were retrieved from supplementary sources, including Google Scholar and manual searches of reference lists, yielding a combined total of 1,160 records.

After the removal of 218 duplicate entries, 942 unique records remained for title and abstract screening. Based on predefined eligibility criteria, 865 records were excluded during this initial screening phase due to irrelevance, lack of genetic data, or study type (e.g., reviews, in vitro studies, or animal experiments).

The full texts of 77 articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Following detailed evaluation, 70 studies were excluded. The most frequent reasons for exclusion included absence of a healthy control group (n = 19), non-assessment of any three COX-2 polymorphisms of interest (n = 17), incomplete or non-extractable genotypic data (n = 18), and insufficient sample size (n = 16).

Ultimately, 7 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. These studies provided sufficient data to be incorporated into quantitative meta-analysis. The complete selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1).

3.2. Study Characteristics

Seven studies were included in the final analysis, published between 2009 and 2023, and conducted across various geographical regions, including Asia and the Middle East. The study populations represented diverse ethnic backgrounds such as Chinese, Indian, Iraqi, and other Asian groups. All included studies employed a case-control design to examine the association between COX-2 gene polymorphisms—specifically -765 G/C, -1195 G/A, and 8473 T/C—and presence of periodontitis.

Sample sizes across studies ranged from 100 to over 400 participants, with a balanced distribution of cases and controls in most studies. Mean participant age, gender distribution, and smoking status were reported variably, although most studies accounted for these factors during recruitment or analysis. All three COX-2 polymorphisms were not universally evaluated across studies; some focused exclusively on one or two variants.

The key characteristics of the included studies are summarized in

Table 1.

3.3. Risk of Bias Within Studies

The methodological quality of the seven studies included in this meta-analysis was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). This tool assesses studies across three domains: Selection (up to 4 points), Comparability (up to 2 points), and Exposure (up to 3 points), giving a total score ranging from 0 to 9.

Only two studies, Li and Loo [

13,

14] achieved scores of 7, indicating high methodological quality, primarily due to appropriate control selection, valid outcome ascertainment, and adequate control for confounding variables. Xie

14 received a score of 6 and was classified as moderate quality, lacking points in control selection domains.

The remaining four studies—Prakash [

6], Dahash [

13], Daing [

18], and Dienha [

17]—were rated as low quality, with total scores ranging from 4 to 5. Most of these studies lost points due to non-representative case selection, absence of detailed control group selection criteria, and limited control for confounding factors such as smoking status or systemic health.

Overall, only 2 out of 7 studies (29%) were classified as high quality (NOS ≥ 7), while 1 was moderate quality, and 4 were low quality (≤5 points). These assessments were used to inform subgroup and sensitivity analyses, evaluating whether methodological quality influenced the pooled effect estimates.

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) Assessment of Included Studies.

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) Assessment of Included Studies.

| Study |

Year |

Case Def. |

Case Rep. |

Control Sel. |

Control Def. |

Confounding |

Exposure Asc. |

Same Method |

Non-Resp. |

Total Score |

Quality |

| Li et al. |

2012 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

High |

| Loo et al. |

2011 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

High |

| Xie et al. |

2009 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

Moderate |

| Prakash et al. |

2015 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

Low |

| Dahash et al. |

2022 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

Low |

| Daing et al. |

2012 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

Low |

| Dienha et al. |

2023 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

Low |

4. Results of Individual Studies

Seven studies evaluated the association between COX-2 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis. For the -765 G/C polymorphism, three studies reported dominant model comparisons (GC+CC vs. GG) and found varied strengths of association, with Li [

15] and Loo

16 showing statistically significant increased risk, while Prakash

6 reported a non-significant association. For the -1195 G/A polymorphism, four studies provided dominant model comparisons (GA+AA vs. GG), with Xie [

14] and Dienha [

17] showing significant associations, while Prakash

6 and Daing [

18] reported non-significant findings.

Table 3 summarizes the genotypic distributions and the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and

p-values from each individual study

.

5. Synthesis of Results—Meta-Analysis

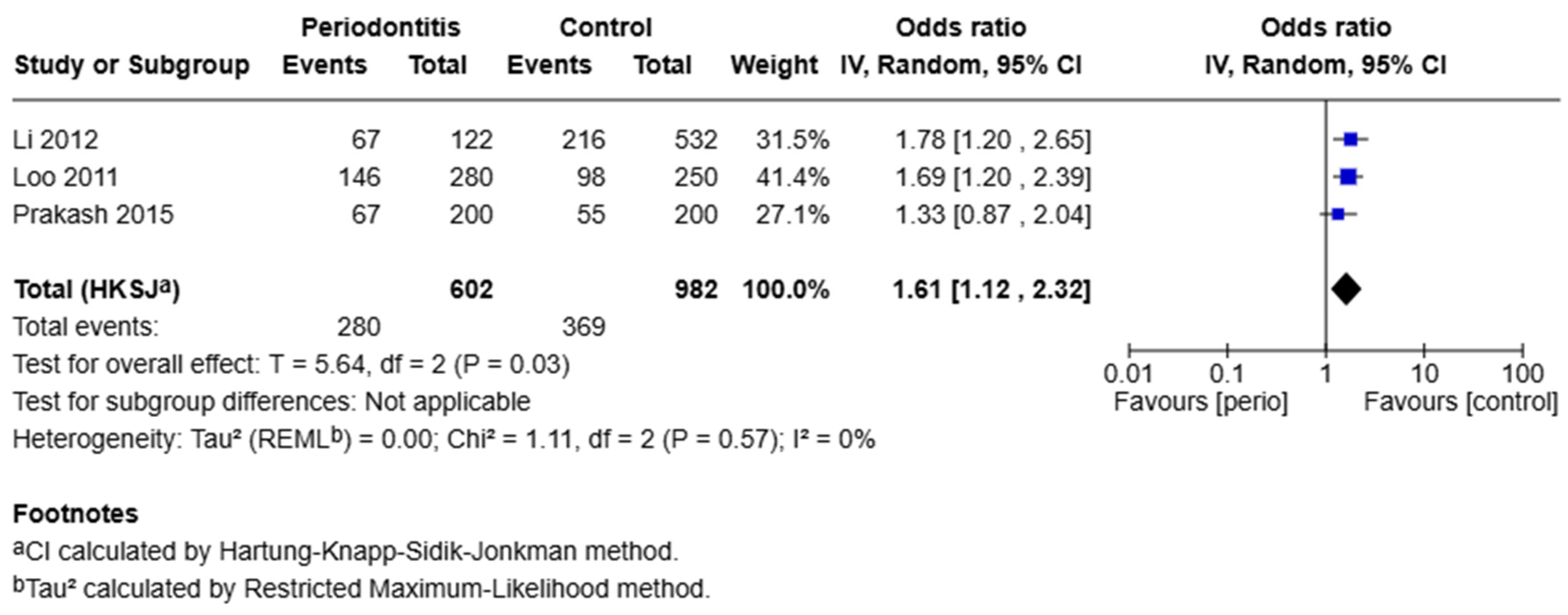

COX-2 -765 G/C Polymorphism

A meta-analysis of three studies evaluating the -765 G/C polymorphism under the dominant model (GC+CC vs. GG) revealed a significant association with chronic periodontitis. The pooled odds ratio was 1.61 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.12 to 2.32 (p = 0.03). Heterogeneity among these studies was negligible (I2 = 0%, Q = 1.11, p = 0.57). This indicates that individuals carrying at least one C allele (GC or CC genotype) have 61% higher odds of developing chronic periodontitis compared to individuals with the GG genotype.”

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the -765 G/C polymorphism under the dominant model (GC+CC vs. GG).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the -765 G/C polymorphism under the dominant model (GC+CC vs. GG).

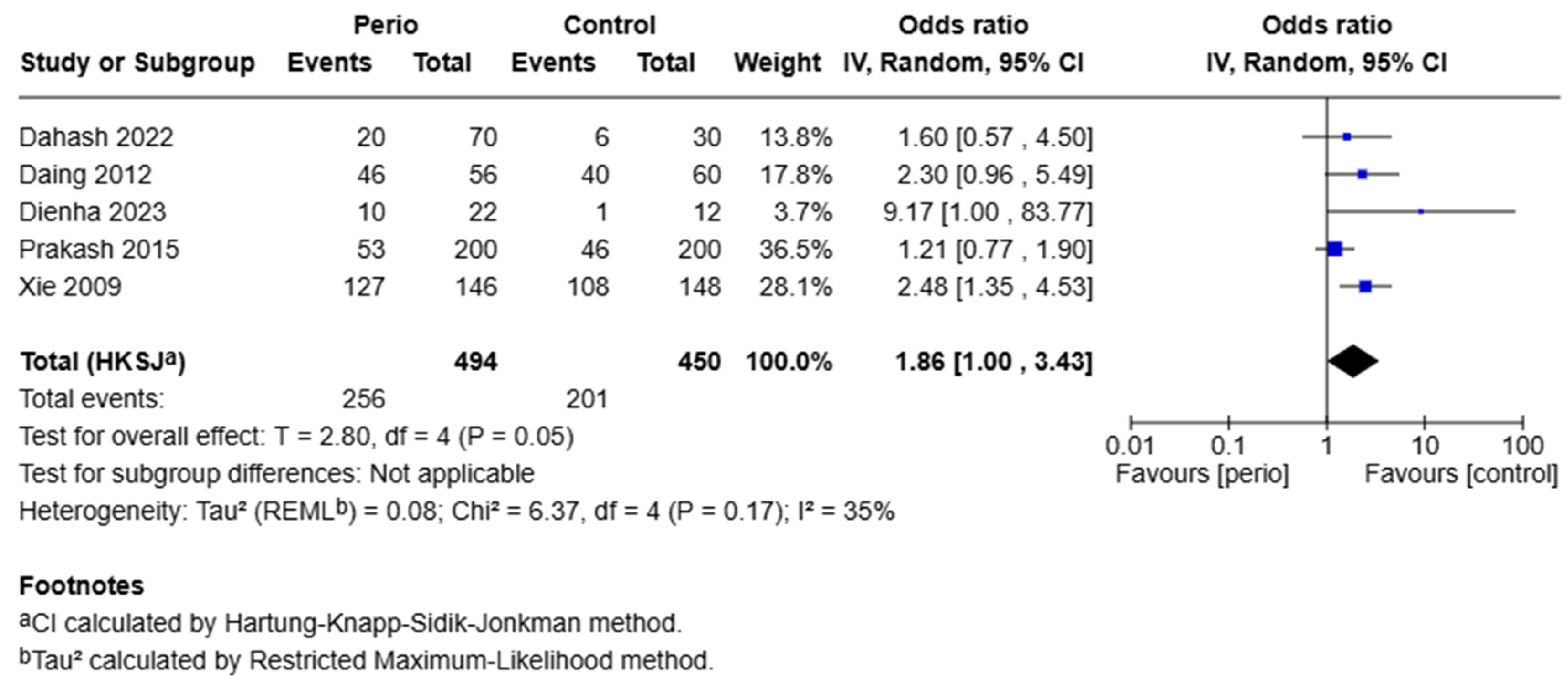

COX-2 -1195 G/A Polymorphism

Five studies were included under the dominant model (GA+AA vs. GG) for the -1195 G/A polymorphism. The pooled odds ratio was 1.86 (95% CI: 1.00–3.43, p = 0.05), indicating a borderline significant association. Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 35%, Q = 6.37, p = 0.17), supporting the use of a random-effects model. The borderline significant OR of 1.86 suggests that carriers of the A allele may have 86% increased odds of developing the disease, although this finding should be interpreted with caution due to moderate heterogeneity and the wide confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the -1195 G/A polymorphism under the dominant model (GA+AA vs. GG).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the -1195 G/A polymorphism under the dominant model (GA+AA vs. GG).

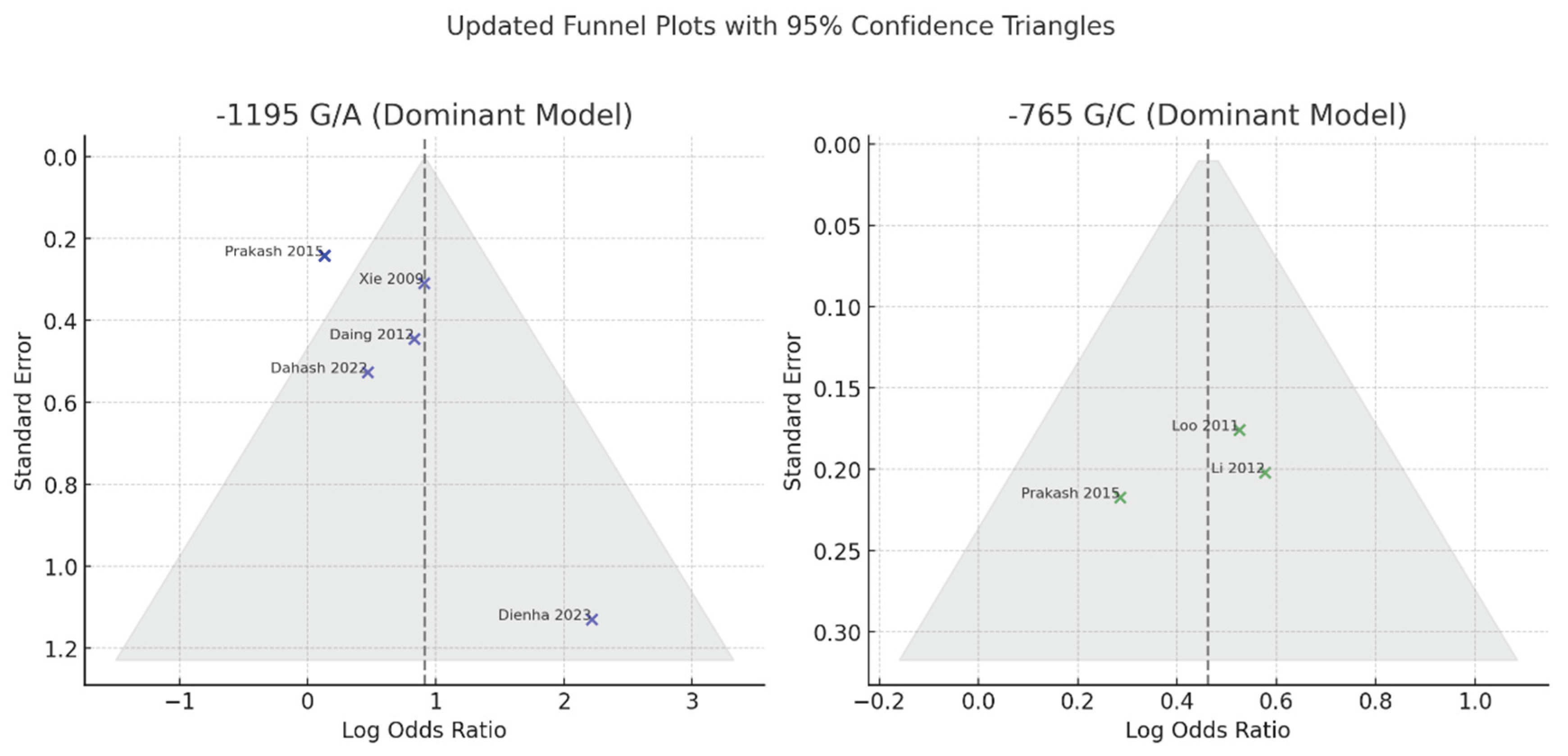

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed for both the -1195 G/A and -765 G/C polymorphisms using visual inspection of funnel plots and consideration of study distribution relative to expected symmetry under a fixed mean effect. Funnel plots were constructed with superimposed 95% confidence boundaries to facilitate detection of asymmetry or small-study effects.

For the -765 G/C polymorphism, the funnel plot appeared symmetrical, and all three included studies, including Prakash [

6] fell within the expected 95% confidence triangle. This indicates a low likelihood of publication bias. Visual findings were consistent with the lack of heterogeneity among studies (I

2 = 0%) and the robust overall effect estimate observed in the meta-analysis.

In the case of the -1195 G/A polymorphism, the funnel plot showed mild asymmetry. Most studies, including Prakash et al. [

6] were correctly positioned within the confidence triangle after rechecking the odds ratio and standard error. However, one study—Dienha [

17] remained a clear outlier with a high odds ratio and wide confidence interval. This suggests the potential influence of a small-study effect or atypical population characteristics. Although Egger’s regression test was not formally conducted in this analysis, the asymmetry observed warrants cautious interpretation of the pooled effect size for this polymorphism.

Figure 4.

illustrates the final funnel plots for both polymorphisms under the dominant genetic model.

Figure 4.

illustrates the final funnel plots for both polymorphisms under the dominant genetic model.

6. Discussion

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is a key inducible enzyme responsible for converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, particularly prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a lipid involved in inflammation, vasodilation, bone and soft tissue degradation in periodontal disease. Given its pathophysiological relevance, genetic polymorphisms within the COX-2 gene have gained considerable attention as potential contributors to inter-individual variability in presence of periodontitis.

In this meta-analysis, we investigated the association of two promoter polymorphisms-1195 G/A and -765 G/C—with the presence of periodontitis. The present findings demonstrated a borderline significant association between the -1195 G/A variant and periodontitis (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.00–3.43, p = 0.05), while the -765 G/C polymorphism showed a statistically significant association (OR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.12–2.32, p = 0.03). These findings suggest a stronger and more consistent contribution of the -765 G/C variant to diagnosis of periodontitis. From the viewpoint of precision medicine, the identified genetic associations have meaningful clinical implications. Including COX-2 genotyping in risk assessments could support more personalized approaches to periodontal care. By identifying individuals with genetic predispositions, clinicians may be able to implement earlier preventive measures and consider tailored adjunctive treatments—such as COX-2 inhibitors—for those likely to exhibit a stronger inflammatory response. This strategy aligns with efforts to provide individualized, evidence-based care in periodontology. The strength of association observed—particularly for the -765 G/C polymorphism (OR = 1.61)—suggests a moderate genetic effect size, consistent with multifactorial traits like periodontitis. The present findings are also supportive of the hypothesis that COX-2 promoter variants contribute to host susceptibility, likely by modulating gene expression and inflammatory response.

The biological plausibility of these associations is grounded in the regulatory role of these polymorphisms in COX-2 gene expression. Variants such as -765 G/C have been associated with altered transcriptional activity, potentially leading to increased COX-2 expression and subsequent overproduction of PGE

2 in inflamed periodontal tissues [

20]. This cascade may accelerate osteoclastic bone resorption and soft tissue degradation—hallmarks of periodontitis pathogenesis.

The present is consistent with prior case-control and meta-analytic studies. Li [

15] and Loo [

16], both included in our analysis, reported significant associations between the -765 C allele and elevated risk for periodontitis in Chinese populations. Similarly, Zhang [

6]

6conducted a meta-analysis exclusively in Chinese individuals and concluded that the -765 G/C polymorphism was significantly increased with periodontitis, particularly in studies using population-based controls. Subgroup analysis in that study found a strong association in the dominant model (GC+CC vs. GG, OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.24–1.86) and even stronger effects under recessive models (CC vs. GG+GC).

Conversely, other studies have yielded conflicting results. For example, Fourmousis and Vlachos [

19] reported a non-significant association in a mixed-ethnicity European cohort, underscoring the potential modifying effects of ethnicity and population structure. Moreover, Prakash [

6] reported non-significant associations in an Indian population, possibly reflecting differences in environmental exposures or gene–environment interactions.

Indeed, ethnicity appears to be a key moderator. In their meta-analysis, Jiang [

12] noted that the A allele of -1195 G/A conferred increased periodontitis risk in Asian populations, but not in Caucasians. Similarly, the results from Zhang [

9] showed opposite effects depending on the source of control, highlighting methodological factors that may drive inconsistency across studies.

Despite the robustness of the present meta-analytic approach, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, the moderate heterogeneity observed in the -1195 G/A analysis (I

2 = 35%) may reflect underlying differences in genetic background, periodontal diagnostic criteria, or environmental factors such as smoking, which was not uniformly adjusted across studies. For example, studies involving the Caucasian population are not included. Second, small sample sizes in several studies, including Dienha [

17], may have led to wide confidence intervals and inflated effect estimates. Third, although publication bias was estimated as minimal for the -765 G/C polymorphism, mild asymmetry was noted in the -1195 G/A funnel plot, suggesting possible small-study effects.

Compared to previous meta-analyses, the present study offers noteworthy advancements. For instance, Zhang [

9] focused exclusively on Chinese populations and did not include the most recent studies from broader geographic regions, such as Iraq, India, and Ukraine. In contrast, our analysis incorporated multiethnic cohorts, thus enhancing the generalizability of the findings beyond a single ethnic group. Furthermore, Jiang

12investigated multiple COX-2 SNPs but included fewer studies per variant and did not account for newer data published in the last decade.

Another important distinction lies in methodological rigor. Our meta-analysis followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, including a more comprehensive literature search strategy across six databases, and applied strict inclusion criteria, excluding studies with inadequate control groups or violations of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Additionally, we conducted funnel plot analysis with 95% confidence boundaries and explored potential small-study effects that were not formally addressed in previous reports.

Therefore, this study not only updates the evidence base but also adds on earlier analyses in terms of study selection, population diversity, and statistical assessment, offering a more robust and current evaluation of the role of COX-2 polymorphisms in periodontitis.

From a clinical standpoint, the present findings suggest that COX-2 promoter polymorphisms, particularly -765 G/C, may contribute to individual risk profiling in periodontal disease. As we move toward personalized periodontal care, genetic screening for high-risk alleles could inform preventive strategies and therapeutic decisions, especially in populations with a high prevalence of these variants. Anti-inflammatory therapies targeting COX-2 pathways may also have enhanced efficacy in genetically predisposed individuals.

7. Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis add to growing evidence that genetic factors significantly influence periodontal disease susceptibility. Specifically, COX-2 promoter polymorphisms like -765 G/C and -1195 G/A may act as functional biomarkers due to their role in regulating inflammatory processes. Integrating these genetic markers into personalized risk models, alongside microbial and lifestyle factors, could enhance the accuracy of risk stratification. This integration would allow for more targeted prevention and treatment strategies, optimizing care for each patient based on their individual risk profile. Future studies should prioritize multiethnic, well-powered, prospective cohorts with standardized diagnostic criteria and genotyping methods. Furthermore, mechanistic investigations linking COX-2 variants to expression levels and PGE2 production in periodontal tissues would deepen our understanding of gene function. Finally, studies examining gene–environment interactions, particularly with tobacco use and microbiological profiles, are crucial for clarifying the complex etiology of periodontitis.

Author Contributions

Vasiliki Savva: Conceptualization; Methodology; Literature search; Study selection; Data extraction; Quality assessment; Formal analysis; Drafting of the manuscript; Visualization; Final approval of the version to be published. Ioannis Fragkioudakis: Methodology; Literature search; Study selection; Data extraction; Statistical analysis; Interpretation of results; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published. Despina Sakellari: Conceptualization; Supervision; Validation of methodology and analysis; Critical revision of the manuscript; Final approval of the version to be published.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

PRISMA 2020 Search Strategy Reporting Template

| SECTION |

ITEM |

REPORTED DETAIL |

| INFORMATION SOURCES |

Name of databases and platforms used |

PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE (via Ovid), Cochrane Library; supplementary: Google Scholar, manual reference screening |

| |

Dates of the search |

Initial search: 11–15 March 2025; supplementary (gray literature and manual reference list screening): 17–20 March 2025 |

| |

Timeframe covered by the search |

From database inception to March 20, 2025 |

| |

Restrictions (language, publication status, etc.) |

Included only peer-reviewed, full-text studies published in English; excluded animal studies, reviews, conference abstracts, and studies with no genotype data |

| SEARCH STRATEGY FOR EACH DATABASE |

Boolean operators, MeSH terms, filters |

See below for full structured search examples per database |

| |

Databases adapted for syntax |

Yes – adjusted syntax for each platform (e.g., MeSH in PubMed, Emtree in EMBASE, TITLE-ABS-KEY in Scopus) |

References

- Bostanci, N.; Bao, K.; Greenwood, D.; Silbereisen, A.; Belibasakis, G.N. Periodontal disease: From the lenses of light microscopy to the specs of proteomics and next-generation sequencing. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2019, 93, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.; Al-Ansari, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.; Alhareky, M.; Gaffar, B.; Almas, K. Global Prevalence of Periodontal Disease and Lack of Its Surveillance. Scientific World Journal 2020, 2020, 2146160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida, S.; Satoh, M.; Takiwaki, M.; Nomura, F. Current status of proteomic technologies for discovering and identifying gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers for periodontal disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PPa Ap Pe Er, R.A.L.; Lazăr, L.; Loghin, A.; et al. O OR RI IG GI IN NA Cyclooxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expressions correlate with tissue inflammation degree in periodontal disease. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015, 56, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, G.; Umar, M.; Ajay, S.; et al. COX-2 gene polymorphisms and risk of chronic periodontitis: A case-control study and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, R.N.; Abramson, S.B.; Crofford, L.; et al. Cyclooxygenase in Biology and Disease. FASEB J. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Båge, T.; Kats, A.; Silva Lopez, B.; et al. Expression of prostaglandin E synthases in periodontitis: Immunolocalization and cellular regulation. American Journal of Pathology. 2011, 178, 1676–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Engebretson, S.P.; Morton, R.S.; Cavanaugh PFJr Subbaramaiah, K.; Dannenberg, A.J. The overexpression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 in chronic periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003, 134, 861–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, H.; Miyaura, C.; Pilbeam, C.C.; et al. Transcriptional Induction of Cyclooxygenase-2 in Osteoblasts Is Involved in Interleukin-6-Induced Osteoclast Formation. Endocrinology 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenbacher, S.; Salvi, G.E. Induction of Prostaglandin Release from Macrophages by Bacterial Endotoxin.

- Jiang, L.; Weng, H.; Chen, M.Y.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, X.T. Association between cyclooxygenase-2 gene polymorphisms and risk of periodontitis: A meta-analysis involving 5653 individuals. Mol Biol Rep. 2014, 41, 4795–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahash, S.A.; Sh, M.; Mahmood, B.D.S. Association of a Genetic Variant (Rs689466) of Cyclooxygenase-2 Gene with Chronic Periodontitis in a Sample of Iraqi Population. Journal of Baghdad College of Dentistry 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C-j, X.; L-m, X.; W-h, F.; D-y, X.; J-c, Z. Common single nucleotide polymorphisms in cyclooxygenase-2 and risk of severe chronic periodontitis in a Chinese population. J Clin Periodontol. 2009, 36, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yue, Y.; Tian, Y.; et al. Association of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, 3, 9, interleukin (IL)-2, 8 and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 gene polymorphisms with chronic periodontitis in a Chinese population. Cytokine. 2012, 60, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, W.T.Y.; Wang, M.; Jin, L.J.; Cheung, M.N.B.; Li, G.R. Association of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-9) and cyclooxygenase-2 gene polymorphisms and their proteins with chronic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienha, O.V.; Pyndus, V.B.; Litovkin, K.V.; et al. DEFB1, MMP9 AND COX2 GENE POLYMORPHISMS AND PERIODONTITIS. World of Medicine and Biology. 2023, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daing, A.; Singh, S.V.; Saimbi, C.S.; Khan, M.A.; Rath, S.K. Cyclooxygenase 2 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis in a North Indian population: A pilot study. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2012, 42, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourmousis, I.; Vlachos, M. Genetic Risk Factors for the Development of Periimplantitis. Implant Dent. 2019, 28, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, E.; Baek, S.J.; King, L.M.; Zeldin, D.C.; Eling, T.E.; Bell, D.A. Functional characterization of cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001, 299, 468–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol. 2018, 45, S149–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).