1. Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED), defined as the persistent inability to attain or maintain penile erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual intercourse [

1], represents a highly prevalent condition globally. Large population-based studies, such as the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) and the European Male Aging Study (EMAS), have reported a prevalence of 52% in men aged 40–70 years [

2], and overall global prevalence is substantial [

3]. ED is known to be multifactorial, associated with numerous medical conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, as well as psychological factors [

1].

Insomnia, characterized by difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or experiencing non-restorative sleep [

4], often with daytime impairment lasting at least three months despite adequate opportunity for sleep [

4], is a common sleep disorder affecting a significant proportion of the adult population. Its prevalence varies across studies and diagnostic criteria, but reviews indicate substantial rates [

5]. For instance, prevalence estimates for insomnia symptoms or clinical insomnia range widely depending on the definition and population studied [

6,

7].

Emerging evidence suggests a strong association between sleep disorders—particularly insomnia—and male sexual function [

7]. A recent large-scale analysis of insurance claims data from 2007 to 2016, involving over 500,000 men diagnosed with insomnia, investigated this relationship [

4]. The prevalence of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep increases linearly with age, affecting nearly 50% of individuals over 65 years old [

8]. The study reported that men diagnosed with insomnia had a 1.58 times greater likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of erectile dysfunction (ED) compared to age-matched controls without insomnia (Hazard Ratio [HR] 1.58; 95% CI 1.54–1.62; p < 0.001) [

4]. Furthermore, men who were both diagnosed and treated for insomnia had an even higher risk, with a 1.66 times greater likelihood of ED diagnosis (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.64–1.69; p < 0.001). Treatment for insomnia was also associated with an increased likelihood of ED being treated with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (HR 1.52) and intracavernosal injections (HR 1.32) [

4]. Other studies using Mendelian randomization have identified insomnia as a highly relevant risk factor for ED (Odds Ratio = 3.44; 95% CI = 1.59–7.43) [

9]. These findings underscore the importance of considering insomnia during the clinical evaluation of patients presenting with erectile dysfunction.

Concurrently, pharmacological treatments for psychiatric conditions, particularly antidepressants, are well-established causes of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction (TESD) [

2,

6,

10,

11]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are among the antidepressant classes frequently implicated, leading to various sexual side effects, including erectile difficulties [

2,

6,

10]. TESD is a common adverse effect that can significantly impair adherence to antidepressant treatment [

2,

6,

10,

11].

The complex interplay between mental health, sleep, and sexual function is recognized. Conditions like depression, often managed with antidepressant medication, are themselves known risk factors for ED2 and frequently coexist with insomnia [

10]. While the associations between insomnia and ED, and between antidepressants and sexual dysfunction/ED, are documented, there remains a notable gap in studies comprehensively analysing the intricate interplay and simultaneous associations among insomnia status, antidepressant use for primary psychiatric disorders, its potential combined effects, and the presence of ED within the same analytical framework. To address this critical knowledge gap and better understand the multifaceted relationship between these prevalent conditions, the present case-control study was designed. Our objective was to investigate the independent and potentially interactive associations of insomnia and antidepressant use with the risk of erectile dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional observational study (cases and controls) was conducted in which adult men over 65 years of age, not hospitalized, participated. Participants were consecutively recruited from general medical outpatient consultations from General Hospital of Zone 1 (Villa de Alvarez, Colima, México) between January-December 2024. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (Registration number: R-2024-601-001, January 26, 2024.). Inclusion criteria included age ≥65 years and availability of complete data on sexual function, comorbidities, and mental health. Exclusion criteria were severe cognitive impairment, active psychiatric disorders requiring hospitalization, and current malignant disease. All information collected for this study was obtained through direct interviews with participants and information obtained from the clinical record. The study followed the guidelines for reporting observational studies (STROBE) [

12,

13].

2.2. Assessment of Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) was assessed using the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5), a validated instrument for evaluating male erectile function. Participants were categorized as having or not having ED based on the scoring algorithm defined by the IIEF-5, with lower scores reflecting greater sexual dysfunction. For the purposes of this analysis, ED was treated as a dichotomous variable based on established cut-off points (<21)[

14].

2.3. Clinical and Psychosocial Variables

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were obtained through structured interviews and medical record review. These included age (analyzed both as a continuous variable and dichotomized as ≥75 years), presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), systemic arterial hypertension (HTN), current alcohol consumption, lifetime tobacco use, insomnia, depression, and antidepressant medication use. Tobacco use was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria as a lifetime history of smoking 100 or more cigarettes. Alcohol use was coded as current consumption (yes/no). Depression was defined as having 5 or more points on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) administered at the time of all participant assessments. If the patient was taking antidepressants but did not comply with the above criteria, they were classified as not depressed. The GDS is a screening tool for assessing depression in older adults [

15]. Antidepressant use was recorded based on current pharmacologic treatment at the time of interview. Insomnia was assessed using the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), a validated tool for measuring sleep disturbances [

16].

2.4. Sample Size and Power Calculation

The sample size was estimated using the formula for the unpaired case-control design, based on the risk of insomnia for developing ED found in a previous study (OR 3.44) [

9], considering a hypothetical proportion of controls with insomnia of 50%, as reported in previous studies [

8]. Using a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power (1-β) of 80%, the required sample size for comparing the groups was calculated to be 49 patients per group (with and without ED). Upon completion of this study, a post hoc statistical power analysis was conducted. The analysis revealed that having insomnia and taking antidepressants (both factors) significantly increase the likelihood of ED. The statistical power for this finding was 90.7%.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics. The normal distribution of the data was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnorf test. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups (with and without SDs) were performed using Student’s t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using logistic regression models. Variables with a univariate association of p<0.05 were included in a multivariate model, and a backward stepwise elimination procedure was applied, with a removal threshold of p=0.1. The final model retained only variables that were independently associated with ED. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to assess the associations between continuous variables: insomnia severity (AIS), depressive symptoms, and erectile dysfunction scores (DISF). To evaluate potential effect modification (interaction) between insomnia and antidepressant use, the population were stratified into four mutually exclusive exposure groups: (1) no insomnia and no antidepressant use (reference group); (2) insomnia only; (3) antidepressant use only; and (4) both insomnia and antidepressant use. Adjusted ORs were calculated for each group using logistic regression. Further examined additive interaction using three standard epidemiological measures: the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), the attributable proportion due to interaction (AP), and the synergy index (S), based on the adjusted ORs from the stratified analysis. These were computed manually from model-derived estimates. These were interpreted using the following thresholds: RERI > 0, AP > 0, or S > 1 indicating potential additive interaction. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) [

17], except for sample size, which was calculated using OpenEpi version 1 (

https://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSCC.htm, accessed April 15, 2025) [

18], and statistical power, which was calculated using ClinCalc version 1 (

https://clincalc.com/stats/Power.aspx, accessed January 18, 2025). A p < 0.05 level was considered statistically significant [

19].

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population by Presence of Erectile Dysfunction

A total of 183 older adult men were included in the analysis (mean age 75.12 ± 7.24 years). Erectile dysfunction (ED) was present in 100 participants (54.6%) and absent in 83 (45.4%).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by ED status. There were no significant differences in age (75.6 vs. 74.5 years; P=0.305), proportion of participants aged ≥75 years (55.0% vs. 49.4%; P = 0.462), or prevalence of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking, or alcohol consumption between participants with and without ED.

However, insomnia and antidepressant use were significantly more common among individuals with ED. Insomnia was reported in 58.0% of those with ED, compared to 41.0% in those without ED (P = 0.026). Similarly, antidepressant use was reported in 55.0% of the ED group versus 37.3% of those without ED (P = 0.018). In general, the type of antidepressants used was mostly Clonazepam (67.4%), followed by Escitalopram (19.8%), Citalopram (7.0%), and Sertraline (5.8%). Although the presence of depression (5 or more points on GDS at the time of evaluation) was higher in participants with ED (51.0% vs. 41.0%), the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.184) (

Table 1).

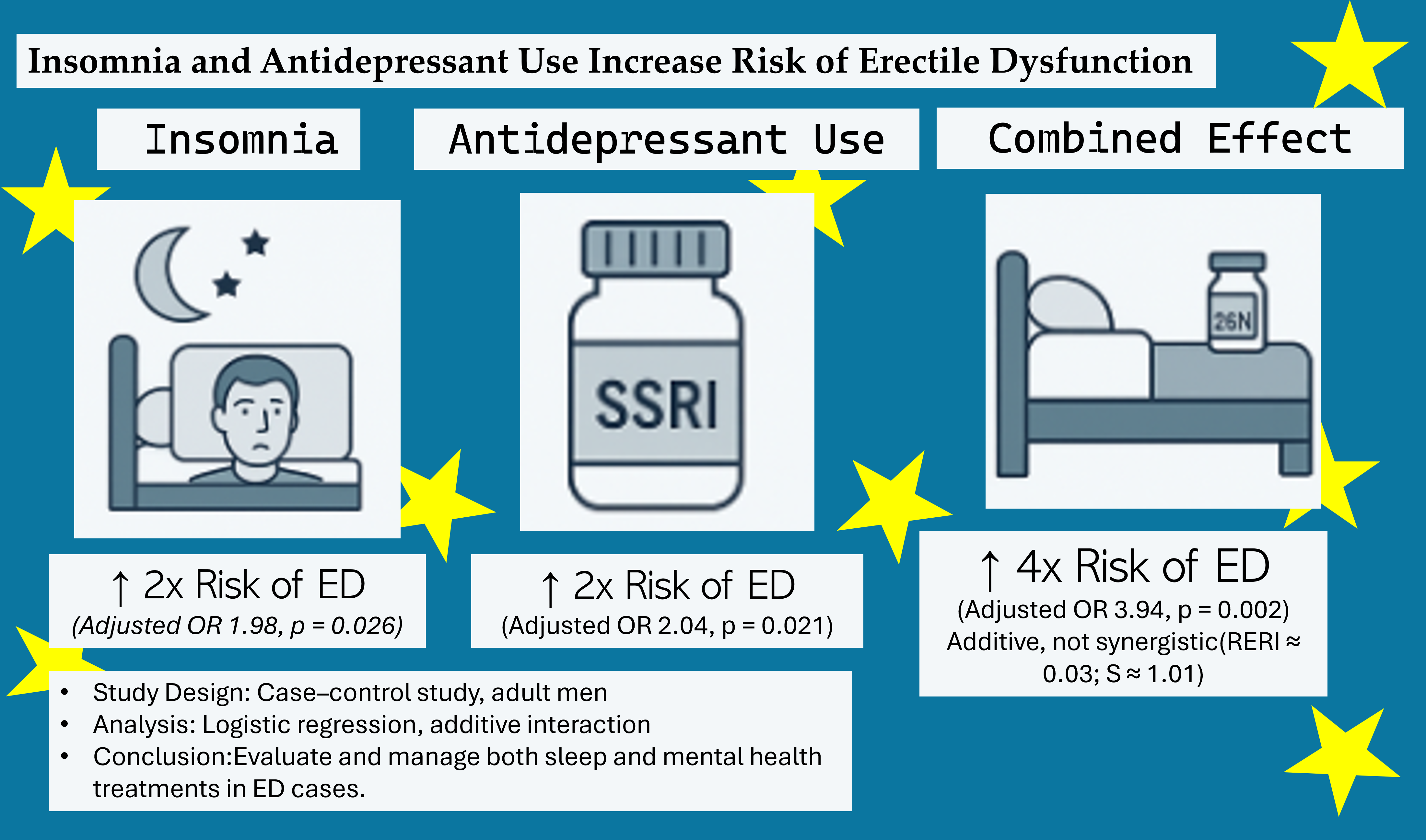

3.2. Independent Risk Factors for Erectile Dysfunction

In the multivariate logistic regression model, two variables remained significantly associated with ED: insomnia and antidepressant use. Both insomnia (aOR: 1.98; 95% CI: 1.09–3.60; p = 0.026) and antidepressant use (aOR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.12–3.72; p = 0.021) were associated with an approximately twofold increase in the likelihood of ED. No other covariates, such as age >75 years, diabetes, hypertension, tobacco or alcohol use, or self-reported depression, remained significant in the adjusted model (

Table 2).

Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationships between scores, insomnia severity, and erectile dysfunction (ED). A weak but statistically significant positive correlation was observed between insomnia scores and ED (r = 0.197, p= 0.007), indicating that higher levels of insomnia symptoms were associated with greater likelihood of reporting ED. No significant correlations were found between depression scores and either ED (r = 0.076, p= 0.306) or insomnia (r = –0.064, p= 0.393). These findings suggest that insomnia severity is closely linked to ED score, and that there is no association with depressive symptoms.

3.3. Stratified Analysis and Potential Interaction (Effect Modification Analysis)

To further explore whether insomnia and antidepressant use interacted, we conducted stratified analyses. Additive interaction analysis yielded the following: RERI = 0·03, suggesting minimal excess risk due to interaction; AP = 0·76%, indicating that less than 1% of the combined risk is attributable to the interaction itself; S = 1·01, consistent with a purely additive effect. Formal measures of additive interaction (RERI ≈ 0.03; S ≈ 1.01) did not indicate a statistically significant synergistic effect. The joint effect of insomnia and antidepressant use on erectile dysfunction was approximately additive, with an adjusted OR of 3.94, closely matching the expected sum of the individual effects minus one (2.4 + 2.5 − 1 = 3.9) (see

Table 3). The above evidence that the coexistence of insomnia and antidepressant use substantially increases ED risk, the observed combined effect is nearly identical to the sum of their individual effects, substantiating an additive, rather than true biological interaction or synergy between these two risk factors.

4. Discussion

This case–control study in adults aged 65 years or older found that both insomnia and antidepressant use were independently associated with approximately a twofold increase in the odds of erectile dysfunction (ED), with adjusted odds ratios (AdOR) near 2.5 when each factor was present alone. Importantly, the coexistence of insomnia and antidepressant use was linked to a substantially higher risk of ED (AdOR 3.94), indicating an additive effect of these two prevalent and potentially modifiable risk factors.

The antidepressant agents used in this cohort were predominantly clonazepam (67.4%), followed by escitalopram (19.8%), citalopram (7.0%), and sertraline (5.8%). Clonazepam, although primarily classified as a high-potency benzodiazepine rather than a classical antidepressant, it is useful for treatment-resistant depressions [

20] but frequently prescribed off-label for anxiety and insomnia symptoms, especially in older adults. Its role in sexual dysfunction remains less well characterized compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [

21], but evidence suggests that clonazepam can induce sexual side effects such as decreased libido and erectile difficulties, likely through central nervous system depressant effects mediated by GABAergic pathways [

22]. While these effects are generally considered infrequent, some retrospective studies report a notable prevalence of ED among clonazepam users [

23]

SSRIs such as escitalopram, citalopram, and sertraline are well established to cause sexual dysfunction, including ED, via serotonergic enhancement that inhibits dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission critical for sexual arousal and performance [

23]. Among SSRIs, escitalopram and citalopram have a comparable moderate risk profile, while sertraline may have a slightly lower incidence but remains a significant contributor to sexual side effects [

24].

The additive effect of insomnia and antidepressant use on ED risk observed in this study likely reflects complementary pathophysiological mechanisms. Insomnia disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, leading to reduced testosterone levels and endothelial dysfunction mediated by oxidative stress, impairing penile vascular relaxation necessary for erection [

24]. Concurrently, clonazepam and SSRIs may exacerbate sexual dysfunction through central nervous system depression and serotonergic inhibition of sexual neurotransmission, respectively. The combined physiological burden imposed by sleep disturbance and pharmacological effects may additively increase the risk and severity of ED.

While prior studies have extensively documented the sexual side effects of antidepressants and the association between sleep disturbances and ED, there are no studies that quantitatively assess their combined impact. A study reported that antidepressants can be associated with ED, and that they can also cause insomnia as another side effect [

10]. From the above, it could be assumed that antidepressants, in addition to being able to cause ED directly, can also promote it indirectly, as a consequence of the insomnia they can also cause.

Clinically, these findings underscore the need for comprehensive assessment of sleep quality and medication regimens in patients presenting with ED, particularly in older adults who are more susceptible to polypharmacy and sleep disorders. From a clinical standpoint, it suggests that individuals with both risk factors may benefit from tailored interventions, including non-pharmacological strategies for insomnia and careful selection or monitoring of antidepressant therapy. Behavioral interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) have demonstrated efficacy in improving sleep and may indirectly ameliorate ED by restoring hormonal balance and reducing physiological stress [

25]. Additionally, careful selection of antidepressants with lower sexual side effect profiles or dose adjustments may mitigate sexual dysfunction. For patients requiring benzodiazepines like clonazepam, minimizing dose and duration or considering alternative anxiolytics may reduce adverse sexual effects.

This study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the case–control design limits causal inference, and reverse causation cannot be excluded—for instance, ED itself may contribute to sleep disturbances or psychological distress leading to antidepressant use. Second, although multivariate analyses adjusted for key variables, residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as anxiety disorders, cardiovascular disease severity, hormonal imbalances, and use of other medications may influence the observed associations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights that insomnia and the use of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications—including clonazepam as a non-classical antidepressant and SSRIs such as escitalopram, citalopram, and sertraline—independently and additively increase the risk of ED in older men. These results support a multidisciplinary approach to sexual dysfunction in this population, integrating sleep management, pharmacological optimization, and patient education to improve sexual health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-E.; Data curation, I.D.-E. and G.A.H.-F.; Formal analysis, J.V.-R., K.B.C.-P., M.F.-M. and M.R.-S.; Funding acquisition, J.G.-E.; Investigation, A.F.-G.; Methodology, V.Y.N.-A., I.D.-E., G.A.H.-F., J.D.-M., O.G.D.-E., A.S.-A., A.F.-G., J.A.-C., P.C.-S., M.F.-M., M.R.-S. and J.G.-E.; Project administration, J.G.-E.; Resources, J.G.-E.; Software, V.Y.N.-A., I.D.-E., J.D.-M., J.V.-R. and K.B.C.-P.; Supervision, J.G.-E.; Validation, V.Y.N.-A., O.G.D.-E., A.S.-A., J.A.-C. and P.C.-S.; Writing – original draft, I.D.-E. and G.A.H.-F.; Writing – review & editing, I.D.-E. and G.A.H.-F.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (Registration number: R-2024-601-001, January 26, 2024.).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Julio V. Barrios Nuñez from the ICEP Colima, Mexico, for their assistance with English language editing. G.A. Hernandez-Fuentes would like to express their gratitude for the financial support from SECIHTI, Mexico, for his postdoctoral studies (633738). The authors also extend their appreciation to the Health Research Security Institute for its support in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lasker, G.F.; Maley, J.H.; Kadowitz, P.J. A Review of the Pathophysiology and Novel Treatments for Erectile Dysfunction. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2010, 2010, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safak, Y.; Inal Azizoglu, S.; Alptekin, F.B.; Kuru, T.; Karadere, M.E.; Kurt Kaya, S.N.; Yılmaz, S.; Yıldırım, N.N.; Kılıçtutan, A.; Ay, H.; et al. Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction in Outpatients. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Sollie, S.; Challacombe, B.; Briggs, K.; Van Hemelrijck, M. The Global Prevalence of Erectile Dysfunction: A Review. BJU Int 2019, 124, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belladelli, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.A.; Del Giudice, F.; Basran, S.; Muncey, W.; Glover, F.; Seranio, N.; Fallara, G.; Montorsi, F.; et al. The Association Between Insomnia, Insomnia Medications, and Erectile Dysfunction. Eur Urol Focus 2024, 10, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddei-Allen, P. Economic Burden and Managed Care Considerations for the Treatment of Insomnia. Am J Manag Care 2020, 26, S91–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canever, J.B.; Zurman, G.; Vogel, F.; Sutil, D.V.; Diz, J.B.M.; Danielewicz, A.L.; Moreira, B. de S.; Cimarosti, H.I.; de Avelar, N.C.P. Worldwide Prevalence of Sleep Problems in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med 2024, 119, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Jarrin, D.C. Epidemiology of Insomnia. Sleep Med Clin 2022, 17, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiological Overview of Sleep Disorders in the General Population. Sleep Med Res 2011, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yan, P. Causal Relationship between Worry, Tension, Insomnia, Sensitivity to Environmental Stress and Adversity, and Erectile Dysfunction: A Study Using Mendelian Randomization. Andrology 2024, 12, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A.; Nash, M.; Lynch, A.M. Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: Impact, Effects, and Treatment. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2010, 2, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo, A.L.; Montejo, L.; Baldwin, D.S. The Impact of Severe Mental Disorders and Psychotropic Medications on Sexual Health and Its Implications for Clinical Management. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med 2007, 4, e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoden, E.L.; Telöken, C.; Sogari, P.R.; Vargas Souto, C.A. The Use of the Simplified International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a Diagnostic Tool to Study the Prevalence of Erectile Dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 2002, 14, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, M.; Fors, M.; Mullo, S.; González, P.; Viada, C. Internal Consistency of Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS 15-Item Version) in Ecuadorian Older Adults. Inquiry (United States) 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okajima, I.; Miyamoto, T.; Ubara, A.; Omichi, C.; Matsuda, A.; Sumi, Y.; Matsuo, M.; Ito, K.; Kadotani, H. Evaluation of Severity Levels of the Athens Insomnia Scale Based on the Criterion of Insomnia Severity Index. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, W.N.; Benuzillo, J.G.; Carrico, M.S. SPSS and SAS Programming for the Testing of Mediation Models. Nurs Res 2004, 53, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.M.; Dean, A.; Soe, M.M. On Academics : OpenEpi: A Web-Based Epidemiologic and Statistical Calculator for Public Health. Public Health Reports® 2009, 124, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinCalc.com » Statistics » Post-hoc Power Calculator Post-Hoc Power Calculator. Evaluate Statistical Power of an Existing Study. Available online: https://clincalc.com/stats/Power.aspx (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Morishita, S. Clonazepam as a Therapeutic Adjunct to Improve the Management of Depression: A Brief Review. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental 2009, 24, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osis, L.; Bishop, J.R. Pharmacogenetics of SSRIs and Sexual Dysfunction. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 3614–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Khorasani, G.; Azadbakht, M.; Zamani, P.; Ghasemi, M.; Ahmadi, A. Effect of Aloe Cream versus Silver Sulfadiazine for Healing Burn Wounds in Rats. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2010, 18, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fossey, M.D.; Hamner, M.B. Clonazepam-Related Sexual Dysfunction in Male Veterans with PTSD. Anxiety 1994, 1, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, E.; Straw-Wilson, K. Sexual Dysfunction in Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Potential Solutions: A Narrative Literature Review. Mental Health Clinician 2016, 6, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossman, J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: An Effective and Underutilized Treatment for Insomnia. Am J Lifestyle Med 2019, 13, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of participants stratified by presence of erectile dysfunction.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of participants stratified by presence of erectile dysfunction.

| |

|

Erectile dysfunction |

|

| Variable |

All |

No

(n=83) |

Yes (n=100) |

p |

| Age (years) |

75.12+7.24 |

74.51+7.09 |

75.62+7.36 |

0.305 |

| ≥75 years old |

52.50% |

49.40% |

55.00% |

0.462 |

| Diabetes |

51.4% |

51.8% |

51.0% |

0.999 |

| Hypertension |

61.7% |

65.1% |

59.0% |

0.447 |

| Tobacco use |

55.20% |

56.60% |

54.00% |

0.766 |

| Alcohol use |

27.9% |

27.7% |

28.0% |

0.999 |

| Insomnia |

50.3% |

41.00% |

58.00% |

0.026 |

| Depression |

46.4% |

41.00% |

51.00% |

0.184 |

| Antidepressant use |

47.0% |

37.3% |

55.0% |

0.018 |

| Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or percentage, as appropriate. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. |

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Factors Associated with Erectile Dysfunction.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Factors Associated with Erectile Dysfunction.

| |

Biivariate model |

Multivariate model |

| |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

AdOR |

95% CI |

p |

| |

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

| >75 years old |

1.25 |

0.70 |

2.24 |

0.450 |

|

|

|

|

| Type 2 Diabetes (DM2) |

0.97 |

0.54 |

1.73 |

0.913 |

|

|

|

|

| Hypertension (HAS) |

0.77 |

0.42 |

1.41 |

0.401 |

|

|

|

|

| Tobacco use |

0.90 |

0.50 |

1.62 |

0.722 |

|

|

|

|

| Alcohol use |

1.29 |

0.71 |

2.35 |

0.408 |

|

|

|

|

| Depression |

1.50 |

0.83 |

2.70 |

0.176 |

|

|

|

|

| Insomnia |

1.99 |

1.10 |

3.59 |

0.022 |

1.98 |

1.09 |

3.60 |

0.026 |

| Antidepressant use |

2.05 |

1.13 |

3.71 |

0.018 |

2.04 |

1.12 |

3.72 |

0.021 |

| OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DM2 = type 2 diabetes mellitus; HAS = systemic arterial hypertension. In the multivariate model, only insomnia and antidepressant use remained statistically significant (p< 0.05). |

Table 3.

Stratified analysis of the combined effect of insomnia and antidepressant use on erectile dysfunction.

Table 3.

Stratified analysis of the combined effect of insomnia and antidepressant use on erectile dysfunction.

| Group |

n |

Insomnia |

Antidepressant use |

% with ED |

AdOR |

95% CI |

P |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

| 1 Reference |

50 |

No |

No |

36.0% |

Reference |

|

|

|

| 2 Insomnia only |

47 |

Yes |

No |

57.4% |

2.40 |

1.06 |

5.43 |

0.036 |

| 3 Antidepressants only |

41 |

No |

Yes |

58.5% |

2.51 |

1.07 |

5.86 |

0.033 |

| 4 Combined effects |

45 |

Yes |

Yes |

68.9% |

3.94 |

1.67 |

9.26 |

0.002 |

| aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The reference group (no insomnia and no antidepressant use) served as the comparator. The combined effect of both exposures was additive, with no statistically significant synergistic interaction observed (RERI ≈ 0.03; S ≈ 1.01). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).