Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. What: Money as Decision-Space

- Person A (broke) can walk, sit in Central Park, read at the library. They have some agency, but operate within tight boundaries.

- Person B (wealthy) can do everything Person A can do, plus: eat anywhere, stay anywhere, attend events, leave the city at will, hire help, buy time.

- Objective: the physical, legal, and logistical space of possible action. This is what money directly expands.

- Perceived: the felt sense of control, shaped by trauma, belief, and expectation.

2. So What: Why It Matters

- The happiness–income paradox: Research has long conflicted on whether money buys happiness. Kahneman and Deaton (2010) found emotional well-being plateaus at $75 k.[1] Killingsworth (2023) shows happiness continues to rise for most people.[2] The tension dissolves once we separate objective agency from perceived well-being: money always expands the former; the latter depends on psychology.

- Individual strategy: If what makes you happy costs little, you don’t need much money. If your goals require travel, flexibility, or investments, you need more. The key question isn’t "How much money do I want?" but "What do I want to be able to do?"

- Policy precision: Cash transfers, UBI, and micro-finance work because they expand viable choices, not because they inject pleasure. Success should be measured in newly feasible actions, not ambiguous “happiness scores.”

- Design implication: Societies can expand real freedom without making everyone rich. Public transit, broadband, and legal simplicity are infrastructure for agency.

The Happiness Paradox Explained

- Agency infrastructure: Universal healthcare, free education, reliable public transit, and strong safety nets dramatically lower the personal cost of exercising choices. Citizens enjoy large decision-spaces without needing high income.

- Low friction, low fixed costs: Walkable cities, affordable housing, and simple bureaucracy reduce everyday friction. Result: high agency at low income levels.

-

Agency-Adjusted Income (AAI): Raw income is a misleading signal. What matters is how far your income stretches—how many viable options it unlocks. We define:A city where income and cost of living both rise by 100% gives you no net gain in agency (). A region with 25% higher income but baseline costs yields : more real choices with less nominal money. Policy should track AAI (or agency-per-capita), not GDP or median wages.

- Geo-arbitrage and migration flows: Immigrants come to the U.S. not for guaranteed wealth, but for greater upward mobility.[6] Conversely, digital nomads leave high-cost cities for places like Thailand or Mexico, stretching their decision-space via geo-arbitrage (relocating to cheaper regions to stretch income).[7] Both behaviors reveal the same principle: people move to optimize for agency, not just money.

| Prediction: Aggregate well-being tracks agency-per-capita more reliably than GDP-per-capita. Countries that invest in “agency infrastructure” (healthcare, transit, legal simplicity) consistently outperform richer peers on happiness metrics.[5] |

The American Promise as Agency Architecture

Now What: Designing for Agency

- Policy: Track agency-per-capita, not GDP. Invest in infrastructure, broadband, and legal clarity to expand freedom without demanding high personal income.

- Mental health: Depression often manifests as a collapse of perceived agency. Restoring an individual’s internal map of choices is integral to restoring their wellbeing.

- Urban design: Build cities for choice-flow: flexible transit, access to nature, and frictionless civic systems. A well-designed city increases agency per dollar spent.

- Inequality: The real divide is not merely income; it is the number of available pathways. Closing the agency gap benefits everyone, not just the poor.

3. Conclusion: Rethinking Money, Reclaiming Freedom

- Why some low-income countries outperform wealthy ones on happiness.

- Why people migrate toward perceived freedom and relocate for geo-arbitrage.

- Why depression feels like entrapment.

- Why wealth doesn’t guarantee fulfillment.

- Why “freedom” is a math problem, not a metaphor.

Appendix A Mathematical Formalization

Appendix A.1. Feasible-Set Definition

- : fixed constraints (time, laws, skills, physics)

- : monetary cost of action x

- M: available money

Appendix A.2. Agency Metrics

- Cardinality (discrete):

- Volume (continuous):

- Entropy (probabilistic):

Appendix A.3. Monotonicity Lemma

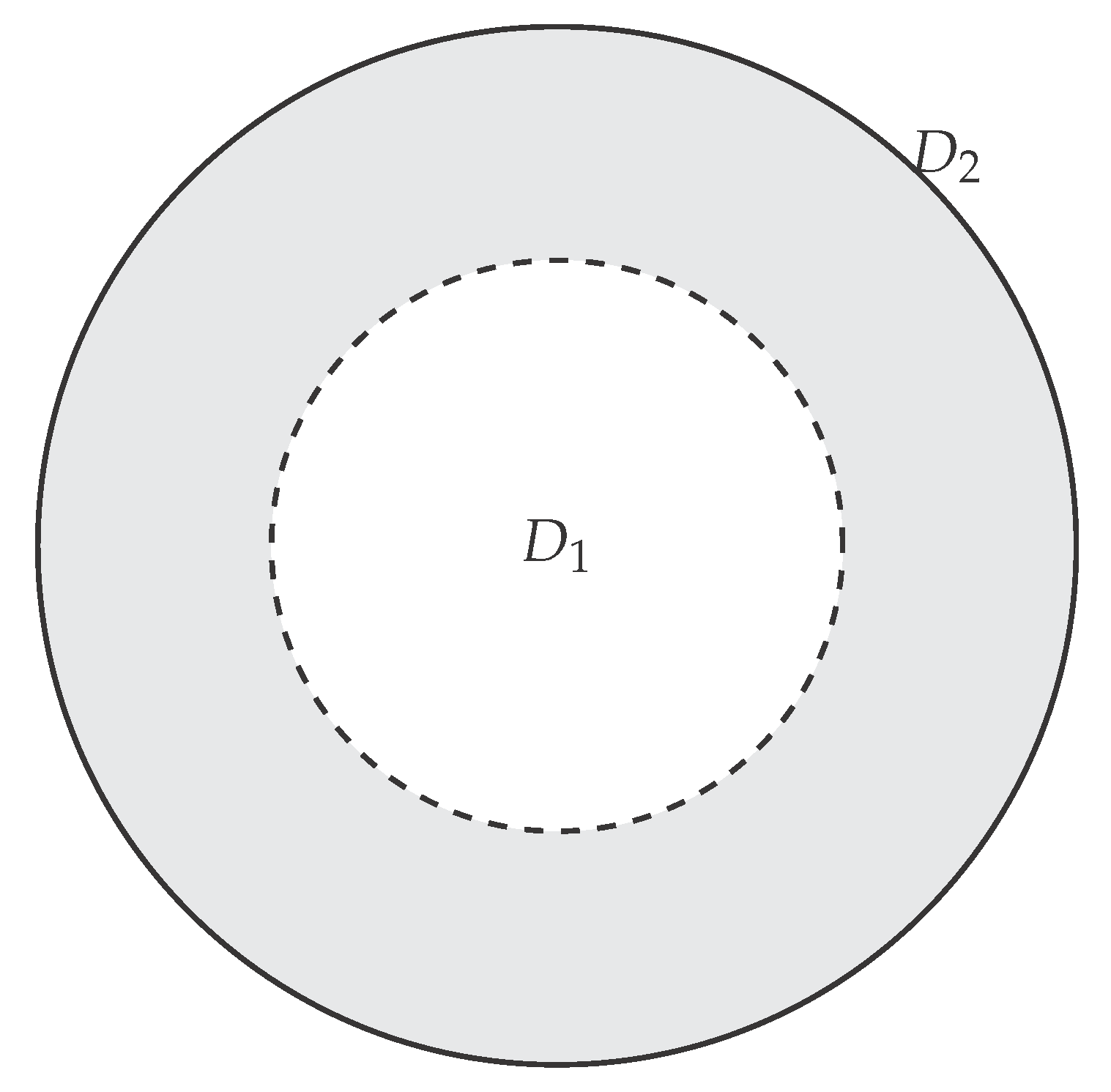

Appendix A.4. Visual Illustration

Appendix A.5. Objective vs. Perceived Agency

- Objective agency: The full structural option set —physically, legally, and logistically possible moves.

- Perceived agency: The subset an agent believes they can act on—shaped by psychology, trauma, or belief.

References

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Angus Deaton. “High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (38), 2010, 16489-16493.

- Killingsworth, Matthew A., Daniel Kahneman, and Angus Deaton. “Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120 (11), 2023, e2204912120.

- Helliwell, John F., Richard Layard, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, et al. World Happiness Report 2025. Wellbeing Research Centre (Oxford), Gallup, and United Nations SDSN, 2025.

- “Costa Rica climbs in 2025 World Happiness Rankings.” The Tico Times, 20 March 2025.

- Associated Press. “Finland again ranked the happiest country in the world as U.S. falls to record low.” AP News, 20 March 2025.

- Abramitzky, Ran, Leah Boustan, Santiago Jácome, and Juan Pérez. “The children of immigrants experience faster upward mobility.” NBER Reporter, Winter 2025.

- “Geo-arbitrage can help digital nomads lead a better life.” andysto.com, 14 September 2024.

- Economic Policy Institute. Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts. EPI, 2023.

- Pew Research Center. “How the American Middle Class Has Changed in the Past Five Decades.” 2022.

- Pew Research Center. “Americans Are Split Over the State of the American Dream.” 2024.

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Anchor Books, 1999.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press, 1959.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).