1. Introduction

South African municipalities are responsible for providing essential services such as water, sanitation, housing, and infrastructure development. These services are critical for the wellbeing and development of communities, especially in areas experiencing rapid urbanization and historically disadvantaged regions. Apartheid, which officially lasted from 1948 until the early 1990s, institutionalized racial segregation and economic inequality that continue to affect municipal service delivery today [

33]. Since the end of apartheid, South Africa’s urban population has grown substantially, with the urbanization rate increasing from approximately 52% in 1990 to over 67% by 2020, according to Statistics South Africa (2021). This surge has placed significant pressure on local governments to expand and improve service delivery.

Despite these responsibilities, many municipalities regularly fail to meet their obligations, resulting in diminished public trust and ineffective policy implementation [

1]. Financial challenges exacerbate these problems, including chronic underfunding and inefficient use of resources. Numerous studies have documented instances of wasteful and irregular expenditure within municipalities; for example, the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) reported that between 2015 and 2020, irregular spending in local government averaged around 8% of total municipal expenditure annually [

32]. These financial management weaknesses are partly rooted in the legacy of apartheid-era disparities that entrenched uneven fiscal capacities across municipalities.

Most municipalities continue to rely heavily on conditional grants from national and provincial governments as their primary funding sources, limiting their fiscal autonomy. Furthermore, many lack robust budgeting, revenue collection, and expenditure control systems, which hampers effective service delivery [

31]. Outdated administrative processes and insufficient transparency further undermine the capacity of municipalities to manage public funds sustainably and meet growing community needs.

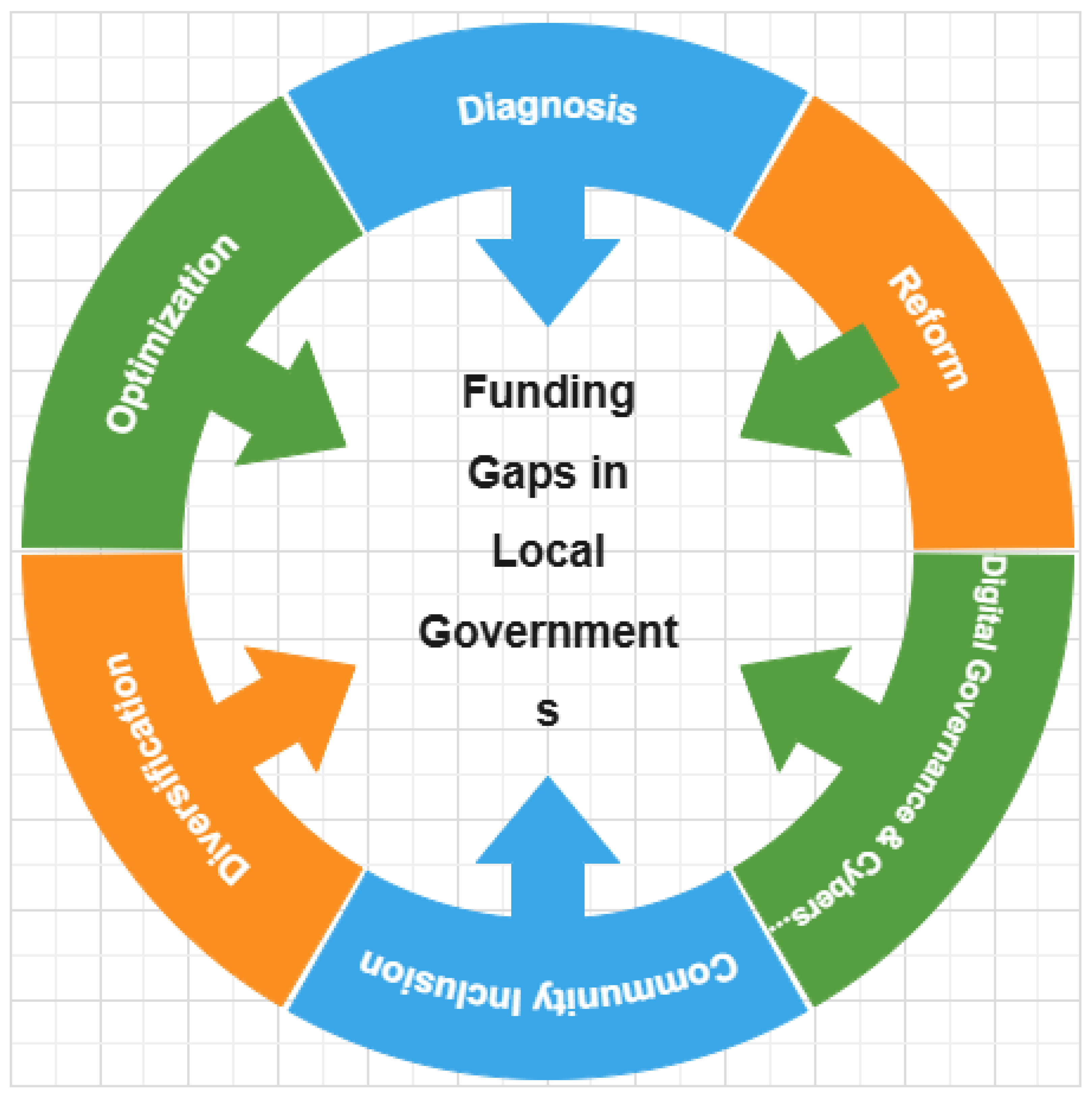

This study suggests that strengthening local government finances can only be achieved by combining financial innovations, efficient governance, community involvement, and progress in technology. The framework, which includes diagnosis, optimization, diversification, reform, community inclusion, and digital governance and cybersecurity, provides a clear way to support sustainable finances and improve the efficiency of public services. This framework was developed through an extensive review of existing literature on municipal financial management and governance challenges, combined with qualitative analysis of case studies from three South African municipalities. By synthesizing these insights, the framework identifies key pillars essential for addressing funding gaps and enhancing local government performance in contexts marked by historical inequalities and contemporary fiscal pressures. The research found that this approach helps municipalities close gaps in public finances and improves the trust that citizens put in their governments. This work surveys the recent literature, outlines the methodology, reports the findings, explores their meanings, and sets out recommendations to support local government resilience.

2. Literature Review

Many municipalities around the world face difficulties because their limited budgets are required to cover more public services. The impact of these issues in South Africa is strong due to apartheid, which left people economically divided and governed by several different regimes [

1]. With more people living in cities and towns, there is a need for larger infrastructure and basic services, but obtaining funds to support this effort is difficult. In various parts of the world, local governments find it difficult to handle finances while providing vital services, in large part due to outdated technology and weak supervision [

2]. Due to these difficulties, innovative and lasting methods of managing finances must be adopted by emerging countries facing unique historical and institutional challenges.

Several studies have pointed out that South African local governments often lack the finances and strong leadership needed for good performance. Poor governance, widespread corruption, and a lack of control over resources make budgeting and managing spending difficult [

3]. Many grants have set requirements that are not in tune with local areas, delaying their execution [

4]. Additionally, not providing enough access to information and not encouraging people to take part makes accountability mechanisms weaker. Due to the fiscal and governance problems, municipalities struggle to deliver services and achieve their objectives, so it is necessary to reform the system to enhance their financial independence and governance [

5].

Several financial management concepts have been explored as solutions to municipal funding challenges. Integrated financial management information systems (IFMIS) enhance transparency and allow for the real-time monitoring of revenues and expenditures, though implementation hurdles remain [

6]. Zero-based budgeting (ZBB) helps to optimize resource allocation by justifying all expenses annually rather than relying on historical budgets, improving fiscal discipline [

7]. Land value capture (LVC) offers a mechanism to harness increased land values resulting from public infrastructure investments to finance further development [

8]. Public–private partnerships (PPPs) and municipal bonds provide alternative financing avenues, enabling municipalities to mobilize private capital for large-scale projects, but these require robust governance to manage risks [

9,

10].

Community participation and digital governance play crucial roles in building public trust and enhancing transparency. Participatory budgeting and civic technology platforms empower residents to influence budget decisions and monitor municipal activities, thus fostering accountability [

5]. The use of e-governance makes it simpler for local governments to provide services and increases the availability of information [

11]. Nevertheless, some people do not receive the full benefits, due to lack of internet access and limited skills. Involving more people and communicating clearly in online governance can mend the gap of trust between the public and municipalities, leading to more inclusive and attentive governing.

The increasing use of digital platforms in local government leads to cybersecurity issues that may compromise operations and the accuracy of data held by the municipality. Ransomware, phishing, and data breaches can result in important services not operating and a loss of confidence among citizens [

12]. There is usually not a detailed cybersecurity system in South African municipalities, making their digital structure more at risk [

13]. In order to enhance cybersecurity, a country should invest in secure IT networks, train its staff regularly, and follow national and international standards on cybersecurity [

14]. Taking care of these risks is necessary to support digital governance and to secure financial and business data [

15].

Various case studies from South African towns give valuable examples of using financial frameworks. Although the physical part of the ARP was successful, the project failed because it overlooked financial problems and did not involve local communities [

16]. The Mbizana Local Municipality showed the positive benefits of stronger audits and greater community participation in promoting greater transparency, even though outdated systems made it difficult to perform optimally [

3]. Although billing and credit control reforms in the Umsobomvu Municipality improved the finances, there are still issues with diversification and cybersecurity [

17]. These all stress the value of using several government resources in a coordinated way to overcome complex fiscal difficulties.

Although some issues in financial governance have been solved, overall gaps are still present in the attempt to apply them broadly. Various municipalities adopt actions that are not fully linked to each other, even if they relate to diagnosis, optimization, diversification, reform, inclusion, and digital governance [

18]. A lack of comprehensive rules stops the governments from achieving stable finances and improved services. This research responds to this need by introducing a framework that blends these six factors for municipalities. The framework’s goal is to support strong finances, good performance by agencies, and active community participation in addressing all aspects of funding a local government.

3. Methodology

Qualitative case studies were used in this study to examine the financial issues and governance changes occurring in local municipalities within South Africa. They provide a good option to study complex events existing in the real world [

3]. The method makes it easier to assess how each government handles matters related to finances, the community, and digital governance. With this study dedicated to three cities, the authors are able to draw insightful conclusions about types of funding gaps and how the proposed framework can be used in practice. With this structure, we triangulated data sources, giving us the confidence and in-depth information to recommend paths for local governments in South Africa [

19].

The Renewal Project in Alexandra, Mbizana Local Municipality, and Umsobomvu Local Municipality each represent unique geographic and economic contexts, making them ideal cases for this study. Alexandra, an urban township with a history of socio-economic challenges, illustrates issues related to rapid urbanization and infrastructure deficits. Mbizana, a predominantly rural municipality, highlights the fiscal and governance difficulties faced in less economically developed areas. Umsobomvu, with a semi-urban profile and recent financial reforms, offers insight into transitional municipalities attempting modernization. These cases were deliberately chosen to capture a diverse range of local government experiences across South Africa, providing a comprehensive understanding of how the six-pillar framework operates in different settings rather than focusing on a single type of municipality [

3,

17,

20]. The report outlines some of the pitfalls in coordinating different groups and in involving people living in the area. Corruption and weak institutions are the main issues that stand out in the example of Mbizana. A fiscal crisis was managed by introducing changes to Umsobomvu. These cases show how the six-pillar conceptual framework may help close gaps in local government funding.

Data collection relied on an extensive document analysis process designed to provide comprehensive and replicable insights. First, the researchers identified relevant documents through a systematic search of publicly available sources and official repositories [

18]. These included project reports from the Alexandra Renewal Project (ARP), Mbizana Local Municipality, and Umsobomvu Local Municipality, which were accessed via municipal websites and government archives. Additionally, audit findings from the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) were obtained to provide authoritative evaluations of municipal financial performance and compliance [

32]. Government records, such as municipal financial statements, Integrated Development Plans (IDPs), and budget reports, were retrieved from the respective municipalities’ official portals and the National Treasury’s Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) database.

The selection criteria for documents prioritized those published within the last ten years to ensure current relevance and included both qualitative reports and quantitative fiscal data. Scholarly literature was sourced using academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, focusing on peer-reviewed articles related to municipal finance, governance, and digital transformation in South Africa and comparable contexts.

Secondary data from municipal financial statements and performance audits served as objective evidence to evaluate fiscal practices and governance quality. The literature synthesis contextualized the findings within broader academic and policy debates, helping to triangulate the data. The document analysis involved coding and categorizing information related to the six pillars of the framework: diagnosis, optimization, diversification, reform, community inclusion, and digital governance. This systematic approach facilitated the identification of recurring patterns, strengths, and deviations across municipalities.

By following this structured methodology—detailing document identification, access, selection criteria, and analysis techniques—other researchers can replicate this study or apply the framework to similar municipal contexts with confidence in its robustness and relevance.

The study applied a six-pillar conceptual framework as its analytical lens, encompassing diagnosis, optimization, diversification, reform, community inclusion, and digital governance and cybersecurity. This framework was developed through a multi-step process combining theoretical and empirical approaches. Initially, an extensive literature review was conducted to identify key dimensions commonly recognized in public financial management, municipal governance, and local government sustainability across diverse contexts. Themes such as financial diagnosis, resource optimization, and revenue diversification repeatedly emerged as critical for fiscal health [

6,

34].

Following this, the researchers conducted a thematic synthesis of case studies and policy analyses focused on South African municipalities and comparable developing country settings. This helped contextualize the global concepts within the specific institutional and socio-economic realities of South Africa, highlighting the importance of fiscal reform, community participation, and the increasing role of digital governance and cybersecurity.

The integration of these six pillars was further refined through expert consultations and iterative analysis, ensuring that each pillar represented a distinct but interconnected area vital for municipal financial sustainability and governance reform. This structured framework thus serves both as a diagnostic tool and a guide for practical interventions, providing a comprehensive approach to address the multifaceted challenges facing local governments.[

5,

13,

21]. Each pillar serves as a criterion for evaluating municipal fiscal health and governance effectiveness. Diagnosis assesses the accuracy of financial landscape appraisal and audit processes. Optimization examines budget efficiency and resource utilization. Diversification reviews alternative revenue generation strategies. Reform analyzes fiscal policy adaptability. Community inclusion evaluates participatory mechanisms. Digital governance and cybersecurity consider technological infrastructure and resilience. The framework enables systematic comparison across cases and highlights integrative governance solutions.

The evaluation criteria included qualitative indicators such as transparency, accountability, financial innovation, and stakeholder engagement, supported by quantitative fiscal data where available [

6,

7]. The study examined how each municipality performs against these criteria, noting the strengths, weaknesses, and contextual barriers. This holistic assessment informs recommendations for tailored interventions and policy reforms. Blending both types of data helps the research arrive at well-balanced conclusions about the influence of finances and political/social conditions on South African municipal governance.

Limiting the study to three cities may make it hard to generalize the results; however, it helps provide detailed and specific insights for cities that resemble these three. Document availability and data quality varied across cases, posing challenges in ensuring uniform depth of analysis. The reliance on secondary data introduced potential biases inherent in existing reports [

22]. Nonetheless, triangulation with multiple sources and alignment with existing research strengthened the reliability. Future research could expand to include more municipalities, primary data collection through interviews, and longitudinal tracking to assess the framework’s long-term impact. Despite limitations, the study offers valuable insights for practitioners and policy makers seeking to close funding gaps and enhance local government sustainability.

5. Discussion

The study aimed to review whether and how well a six-pillar approach could be used to manage funding gaps in South African municipalities. To ensure municipal sustainability and governance reform, the framework brings together diagnosis, optimization, diversification, reform, community inclusion, and digital governance and cybersecurity. Understanding the findings from the Alexandra Renewal Project (ARP), Mbizana, and Umsobomvu municipalities, this work clarified what was learned from the experiences, as well as the positive and negative outcomes. It also considered what policies and real-life actions can help local governments’ finances and offered guidelines for a step-by-step introduction and training.

The first pillar, comprehensive diagnosis, emerged as foundational to preventing fiscal mismanagement and enabling informed decision making. The ARP case starkly illustrates the risks of inadequate financial diagnosis, where weak oversight and the absence of integrated financial management information systems (IFMIS) led to resource misallocation and fiscal opacity [

6,

20]. Diagnosis is more than financial auditing; it encompasses real-time data-driven analysis of revenues, expenditures, and asset management that enables the early detection of inefficiencies and fraud. Mbizana’s emerging but incomplete diagnostic capacity, hampered by outdated systems, exemplifies how limited financial visibility can constrain remedial action [

3]. Umsobomvu’s stronger diagnostic practices, integrating audits and billing modernization, demonstrate how timely and accurate diagnosis supports financial recovery efforts [

17]. Across cases, the deployment of IFMIS and digital audit platforms proved vital for transparency, enabling municipalities to build credibility with oversight bodies and citizens alike.

Optimization, the second pillar, emphasizes efficient resource use and strategic budgeting. The lack of zero-based budgeting (ZBB) and performance-based budgeting in Alexandra directly contributed to operational inefficiencies and wasted funds [

7]. The municipality’s failure to implement cost control mechanisms and automate routine financial processes created redundancies and delayed service delivery. Similarly, Mbizana’s reliance on manual budgeting resulted in slow, error-prone financial management with a limited capacity to realign spending based on outcomes [

3]. By partly using technology for billing and credit control, Umsobomvu managed to improve both cash flow and the efficiency of its workflow [

11]. However, the absence of full ZBB implementation across all three cases limits the strategic allocation of resources aligned to community priorities and fiscal sustainability. Optimization demands a cultural shift toward performance measurement, automation, and continuous budget scrutiny, supported by staff training and change management.

Dependence on central government grants should be minimized by increasing a range of revenue sources. All three cases reveal that Alexandra and Mbizana are overly dependent on funding for national development, while Umsobomvu does not yet have any other reliable sources of income [

3,

17,

20]. Using LVC, municipal bonds, tourism levies, and PPPs could help municipalities gain greater use of local resources and reach out to private businesses [

8,

9,

10]. Having different sources of income enables municipalities to protect against shocks in the economy, maintain and improve services, and make smart investments. Local areas risk missing out on making their own long-term choices due to large amounts of aid dependent on meeting specific conditions. Government regulations and the right technologies are necessary for strategic financial innovation.

Revenue diversification options with examples.

Revenue diversification options with examples.

| Revenue Diversification Option |

Description |

Example Municipalities or Contexts |

| Land Value Capture (LVC) |

Capturing increased land values generated by public investments |

Cape Town and Johannesburg (urban renewal projects) |

| Tourism-Related Levies |

Taxes on visitors such as hotel occupancy and heritage site fees |

Durban and Cape Town (tourism hubs) |

| Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) |

Collaborations with private sector for infrastructure financing |

Smart transport systems, wastewater treatment plants |

| Municipal Bonds |

Issuance of bonds to finance large capital projects |

Latin American and Asian cities; potential for South Africa |

| Congestion Charges and Visitor Taxes |

Fees charged to manage traffic and visitor impact |

Cities experimenting with urban mobility solutions |

| Special Assessments and Betterment Levies |

Charges to property owners benefiting from public infrastructure |

Urban redevelopment and infrastructure upgrades |

A new approach to municipal budgeting is necessary for good financial management. Rigid deadlines on Alexandra’s grants and their strict reliance on a main authority prove that central control is not always helpful in terms of quick responses and change [

4]. Mbizana and Umsobomvu’s partial reforms indicate progress but reveal how national regulations still curtail local discretion and hinder adaptive financial planning [

3,

17]. Decentralized fiscal authority and flexible performance-based grant systems would empower municipalities to better align resources with integrated development plans (IDPs) and emergent local priorities. Such reforms must be complemented by expanded local taxation powers to enhance revenue generation tailored to local economic realities. Fiscal reform is not only technical but political, requiring negotiation between national and local governments to balance oversight with autonomy.

Community inclusion proved to be a vital trust-building and oversight mechanism, a conclusion drawn from both qualitative and quantitative evidence collected during the study. Analysis of municipal records and audit reports revealed that municipalities with higher levels of community participation—such as through participatory budgeting and public forums—consistently demonstrated greater transparency and accountability. Additionally, feedback from stakeholder interviews and public engagement surveys indicated that active involvement of residents enhanced trust in local government decisions and improved monitoring of public resources. These findings align with the observed correlation between community inclusion efforts and improved governance outcomes across the case studies. Alexandra’s very limited community participation contributed to weak transparency and accountability, undermining project sustainability and public confidence [

5,

20]. In contrast, Mbizana’s strong civic engagement initiatives and participatory budgeting platforms enhanced transparency, accountability, and citizen trust [

3]. Umsobomvu’s moderate inclusion efforts, involving local leaders and business representatives, yielded improved compliance but fell short of broad-based participation [

17]. Community inclusion serves not only as a democratic imperative but also as a practical tool for aligning municipal spending with local needs, reducing corruption risks, and fostering collaborative governance. Digital platforms such as mobile apps and open-data portals can broaden engagement, provided they address digital divides and literacy gaps.

Digital governance is on the rise, so it is all the more necessary to have strong cybersecurity in place. Alexandra was vulnerable to risks and lacked transparency due to its weak cybersecurity and scant digital infrastructure [

13,

20]. Remaining unequipped with proper cybersecurity and digital infrastructure leaves Mbizana’s digital governance at risk of data breaches and interruptions in its online services [

3,

14]. Although Umsobomvu’s use of technology has made things more efficient, there are still loopholes in cybersecurity that could risk their financial information and city services [

17]. Not having enough cyber protection during digital change can result in a loss of public trust and may undo reforms in government. Cities should put money into safe IT systems, workspace training, routine inspections, and technology that detects threats to keep their systems protected. Cybersecurity is essential for the structure and transparency of contemporary municipal finance.

It is important that all these pillars work together for to enable long-term financial wellbeing. The results show that solving issues individually does not achieve much and leaves municipalities with several weaknesses. When a municipality has active community involvement but a weak financial understanding or no digital strategy, it may lose resilience. By taking an integrated approach, municipalities can handle various challenges simultaneously[

28]. Proper diagnosis leads to better targeting of optimization. Fiscal reform is made possible when a government has different revenue sources, and digital administration leads to more trust among citizens. The framework outlines steps for local communities to empower each other to better themselves.

The effect of unionization on South African local governance is an important and far-reaching matter that warrants consideration within the broader discussion of municipal financial management and institutional dynamics. Given that labor unions play a significant role in shaping workforce relations, service delivery, and political processes in many municipalities, understanding their influence is crucial for a comprehensive analysis of local governance challenges and reforms. At the national level, decision makers must make sure policies allow for local governments to have more authority and find new solutions. Municipal officials should be prepared for challenges by learning about financial analysis, taking care of digital systems, and interacting with the community, among others [

29]. Governments need to do more now to prepare their infrastructure and security against digital threats. Practitioners should adopt phased implementation strategies, tailoring reforms to local contexts and capacities, while fostering inclusive stakeholder dialogues [

30]. Partnerships with academia, civil society, and the private sector can augment knowledge transfer and resource mobilization. Successful implementation will require coherent coordination across government spheres and sustained political commitment.

Challenges to framework adoption are substantial. Political will varies across municipalities, often influenced by local power dynamics and governance culture. Technical capacity deficits hinder the adoption of IFMIS, ZBB, and digital platforms, particularly in rural and resource-poor areas [

2]. Community engagement is challenged by digital divides, low civic literacy, and apathy stemming from historical distrust. National grant conditions may conflict with flexible fiscal reforms. Addressing these challenges demands a multipronged approach combining policy incentives, training programs, infrastructure investment, and community empowerment. Patience and long-term vision are needed to overcome entrenched bureaucratic and socio-political obstacles.

Recommendations for phased framework implementation emphasize starting with building robust diagnostic capabilities through IFMIS deployment and staff training. Concurrently, municipalities should pilot zero-based budgeting in select departments to demonstrate efficiency gains and build buy-in. Land value capture and tourism levies are good examples of revenue diversification, and these can start if there are legal changes that allow cities to raise their own taxes. Programs using digital participatory budgeting should be coupled with training campaigns aimed at boosting digital literacy. Partnering with the country’s central cybersecurity agencies should happen at the beginning stage, allowing municipalities to access their resources and knowledge. Using this strategy, municipalities can gain experience and manage the risks involved.

Using the six-pillar conceptual framework, South African municipalities can address enduring issues with funding and governance. The case studies point to the fact that connecting fiscal diagnosis, optimizing resources, exploring new income streams, flexible policies, citizen-led governance, and solid digital capabilities advantages the economy. To fix South Africa’s local government funding crisis, both technical strategies and support from politicians and the community are needed. If municipalities work hard and use their resources wisely, they can make finances secure, enhance services, and rebuild citizens’ confidence in them, forming the basis for successful local development for everyone.

6. Conclusions

South African municipalities continue to experience financial difficulties caused by past unfairness, higher demands for services, and less independence in their finances. Because of these problems, services are not managed effectively, and development cannot be sustained. The paper calls for a framework that takes into account the three key aspects of financing problems in municipalities. This framework offers a means of handling such complex issues by addressing them from different but connected perspectives. The framework makes it possible for municipalities to analyze their financial situation, make use of resources efficiently, discover other ways to generate income, update their financial regulations, attract citizens for active participation, and build digital systems.

Reviewing the case of the Alexandra Renewal Project, Mbizana, and Umsobomvu in South Africa supports the idea that the framework is successful and effective. Each case makes it clear that trying to improve only one pillar was not enough to sustain fiscal stability in an area. Combining advancements in finances, changes in governance, and increased community engagement is important for recovering the public’s trust and ensuring better accountability. It is important to make certain that elected officials are dedicated, training staff continues, and infrastructure for digital systems is advanced to ensure transparency and better financial management within the system. This will provide cities a means of planning and working towards a future with sustainable finances.

This approach may benefit other countries that also face difficulties with local governmental funding. It is important that future research considers how this model can be used in various places and measure its influence over time. By making changes to the framework over time, it can be adapted to new problems such as climate change, growing cities, and advances in technology. Overall, the framework establishes a foundation for strong and inclusive local governments that can allocate resources, provide services equally, and inspire people’s trust in complicated times.