1. Introduction

The threat of financial crime remains one of the most resilient and adaptive risks facing the international financial system. Illicit finance, including corruption, money laundering, tax evasion, and regulatory arbitrage, has grown to an enormous and complex scale, with the ability to undermine economic integrity, distort competition, and damage public confidence (Al Qudah, 2024). In recent years, phenomena such as financial globalization and digitalization have opened new channels for such activities, sometimes faster than the institutional settings established to combat them. That asymmetry has left regulators wondering how to maintain financial transparency in a world of ever-nimble financial wrongdoing.

At the same time, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) has generated both excitement and concern among policymakers and scholars. On one hand, AI-related tools and technologies—including anomaly detection systems, pattern recognition software, and predictive algorithms—have significant potential to revolutionize approaches to combating financial crime. These systems can analyze vast amounts of transaction data, uncover hidden relationships among transactions, and learn to flag suspicious behaviors that would be nearly impossible to identify manually. Conversely, these same innovations can also be exploited as weapons in efforts to conceal illegal activities. Deepfake documents, synthetic identities, and algorithmic laundering techniques represent a new frontier of adversarial innovation, where malicious actors use AI to outpace enforcement efforts.

This study is driven by the paradoxical nature of AI’s role in financial regulation. Instead of regarding AI as merely a beneficial or harmful tool, we argue that its impact depends on the institutional environments in which it is employed. In high-integrity jurisdictions with effective governance and transparent oversight, AI may enhance regulatory capacity and deter misconduct. Conversely, in contexts with weak institutions, limited accountability, or regulatory capture, AI may increase opacity or serve as a superficial compliance gesture. Thus, the critical question is not whether AI reduces financial crime, but rather under what conditions it achieves this outcome.

Building on this premise, the study sets out to investigate the following research question:

To what extent does the adoption of artificial intelligence influence financial crime across different institutional contexts?

To answer this question, the paper presents a theoretical and empirical framework that depicts AI as a dual-use infrastructure, which can exert both order and disorder, with its impact mediated by regulatory quality and governance capacity. We employ panel data for 85 countries during the period 2012–2023 and estimate the effects of AI adoption on proxy measures of financial crime (IFFs, TFL, and AML risk scores) using fixed effects and instrumental variable approaches.

This research presents three main contributions. First, it expands the literature on financial crime by incorporating AI as a dynamic explanatory factor, rather than as a passive control or an unexplored black box. Second, it connects the literatures on technology and governance by theorizing the conditional effectiveness of AI tools. Third, it offers empirical evidence regarding the institutional thresholds at which AI becomes a meaningful deterrent.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Chapter 2 surveys the relevant literature on financial crime regulation and the adoption of AI. Chapter 3 outlines the conceptual and econometric models, including definitions of variables and sources of data. Chapter 4 presents the empirical results, along with robustness checks and interaction effects. Chapter 5 examines the ethical and operational limitations of AI in preventing financial crime. Finally, Chapter 6 concludes with key policy recommendations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The intersection between artificial intelligence and financial crime regulation has drawn growing attention across legal, economic, and technological domains. Much of the early academic discourse on financial crime has emphasized institutional capacity, regulatory harmonization, and the role of international frameworks, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), in curbing illicit activity (Levi, 2020; Sharman, 2011). Within this tradition, the emphasis was placed on the structural determinants of compliance, including judicial independence, transparency in enforcement, and bureaucratic efficiency. These works consistently highlighted that the effectiveness of anti-money laundering (AML) frameworks and tax enforcement regimes depends less on legislation per se than on the integrity and capacity of domestic institutions.

As financial ecosystems have digitized, however, scholars have begun to consider the role of technology in transforming both the means and detection of economic crime. A significant body of recent literature examines how AI-based tools improve anomaly detection, transaction monitoring, and risk-based compliance processes. Arner et al. (2024) and Tran and Rose (2022), for instance, demonstrate that machine learning systems outperform traditional rule-based models by adapting to non-linear transaction patterns and flagging subtle inconsistencies. These advancements have allowed financial institutions to reduce false positives, detect layering schemes, and refine client risk profiling with greater precision.

However, the adoption of AI in regulatory contexts also invites critical scrutiny. While algorithmic tools can support compliance, they can just as easily be manipulated to bypass scrutiny. Udayakumar et al. (2023) raise concerns about generative adversarial networks (GANs) and synthetic data engines that simulate legitimate financial behaviors, allowing money launderers to conceal suspicious transactions. Similarly, Zetzsche et al. (2020) highlight the emerging risks posed by decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, where AI agents autonomously manage capital flows without centralized oversight, thereby opening avenues for untraceable tax evasion and cross-border money laundering.

Beyond technical capabilities, scholars have turned to the institutional determinants of AI’s success in financial regulation. Fenwick et al. (2016) propose that successful AI deployment depends on regulatory cultures that are responsive and adaptive. In contrast, jurisdictions with rigid bureaucratic models or opaque decision-making processes may struggle to effectively integrate AI. Feyen et al. (2021) add a comparative perspective, showing that national legal traditions—such as civil vs. common law systems—significantly shape both the adoption rate and operational effectiveness of AI-based compliance tools.

Ethical critiques have also emerged. Zuboff (2023) and Pasquale (2015) argue that unchecked AI deployment risks institutionalizing “black box governance,” where opaque decision-making systems reduce accountability and heighten the potential for discriminatory outcomes. These concerns are particularly salient in the financial sector, where profiling algorithms may unintentionally reinforce racial, geographic, or economic biases, leading to unjustified de-risking or surveillance of marginalized groups (Binns, 2018; Wachter & Mittelstadt, 2019).

Finally, the role of global regulatory coordination has received increased emphasis. Arner et al. (2024) advocate for convergence in AI governance standards to minimize regulatory arbitrage and promote consistency in anti-money laundering (AML) practices. Meanwhile, Mestikou et al. (2023) examine the supervisory role of central banks in overseeing financial AI tools, highlighting the tension between innovation and prudential risk management.

Taken together, the literature points to a consensus: AI is neither a universal solution nor a neutral tool in the fight against financial crime. Institutional context, legal frameworks, and ethical constraints mediate its effects. This study seeks to build on these insights by offering a conditional theory of AI effectiveness—one that explicitly incorporates governance quality and regulatory transparency into empirical analysis.

3. Conceptual and Econometric Framework

This chapter outlines the theoretical basis and econometric design used to investigate the relationship between artificial intelligence and financial crime. It integrates insights from institutional economics, regulatory compliance theory, and technological governance to develop a coherent analytical model. The econometric specifications are then introduced, followed by a justification of variable selection, estimation strategy, and the adoption of the key assumptions.

3.1. Conceptual Framework

Artificial intelligence is increasingly positioned as a regulatory enabler within the global financial architecture. However, its effectiveness is deeply contingent on the quality of institutional frameworks into which it is embedded. From a theoretical standpoint, this research draws on two complementary perspectives:

Institutional Complementarity Hypothesis: Rooted in the works of North (1990) and Rodrik et al. (2004), this view asserts that technological innovations—such as AI—do not function in a vacuum. Existing institutional arrangements, including the rule of law, regulatory independence, and bureaucratic accountability, shape their efficacy.

Conditional Technology Effect Model: Building on Arner et al. (2024)t, we posit that AI reduces financial crime more effectively in jurisdictions with robust legal norms and enforcement capacity. Where institutions are weak or corrupt, however, AI may be co-opted, underutilized, or produce biased outputs.

The resulting hypothesis is that the impact of AI on financial crime is both context-dependent and non-linear, requiring empirical techniques that can capture interaction effects and potential endogeneity.

3.2. Empirical Model Specification

To empirically test the conceptual claims, we specify a fixed-effects panel regression model as follows:

+

where:

represents financial crime indicators (e.g., illicit financial flows or AML risk scores) for country i in year t.

denotes the AI Adoption Index.

captures institutional quality using a composite governance score.

is a vector of control variables (GDP per capita, trade openness, financial depth).

and denote country and year fixed effects.

is the idiosyncratic error term.

This model allows us to evaluate both the direct effect of AI and its conditional interaction with regulatory institutions. We adopt a fixed effects (FE) model to control for unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity across countries, such as legal traditions, geographic factors, or institutional history, which may confound the relationship between artificial intelligence (AI) adoption and financial crime. To validate this choice, we conducted a Hausman specification test, which confirmed the appropriateness of the FE model over the random effects alternative (p-value < 0.05), indicating that the FE estimator provides consistent and efficient results.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables (2012–2023).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables (2012–2023).

| Variable |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

| Financial Crime Index |

4.32 |

1.21 |

1.85 |

6.93 |

| AI Adoption Index |

0.48 |

0.19 |

0.10 |

0.88 |

| Institutional Quality |

0.63 |

0.14 |

0.22 |

0.91 |

| AML Risk Score |

54.7 |

11.3 |

29.5 |

78.9 |

3.3. Endogeneity and Instrumentation

AI adoption is plausibly endogenous. Governments under pressure to curb financial crime may invest in AI, potentially leading to a reverse causality effect. To address this, a two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach is employed. The first stage of instruments AI adoption using:

Both instruments are theoretically exogenous to current financial crime trends but correlated with a country's AI maturity, meeting the relevance and exclusion conditions.

Table 2.

Instrument Validity and Relevance Tests.

Table 2.

Instrument Validity and Relevance Tests.

| Instrument |

First-Stage Coefficient |

Std. Error |

F-Statistic |

P-Value |

| Lagged ICT Investment |

0.213 |

0.034 |

38.21 |

<0.001 |

| AI Strategy Dummy (0/1) |

0.174 |

0.029 |

29.34 |

<0.001 |

| Joint F-Statistic (Instrument Set) |

— |

— |

51.77 |

— |

3.4. Data and Variable Construction

The dataset spans 85 countries from 2012 to 2023. All data are obtained from publicly accessible and peer-validated sources:

Table 3.

Key Variables, Definitions, and Sources.

Table 3.

Key Variables, Definitions, and Sources.

| Variable |

Definition |

Source |

| AI Adoption Index |

Composite index of AI R&D spending, AI strategy adoption, and startups |

Oxford Insights, OECD AI Policy |

| Illicit Financial Flows |

Proxy for unrecorded cross-border outflows linked to illicit activity |

Global Financial Integrity (GFI) |

| AML Risk Score |

Country-level score indicating anti-money laundering risk |

Basel Institute AML Index |

| Institutional Quality |

Average of World Bank rule of law, corruption control, and government effectiveness |

World Governance Indicators (WGI) |

| GDP per capita (log) |

Economic control variable (constant USD) |

World Bank |

| Trade Openness |

Sum of exports and imports as % of GDP |

IMF World Economic Outlook |

| Financial Depth |

Private sector credit to GDP (%) |

Global Financial Development Database |

3.5. Estimation Strategy and Robustness Design

The empirical analysis proceeds in three stages:

Fixed-effects panel regression to account for unobserved heterogeneity.

2SLS regression to correct for potential endogeneity.

Robustness checks, including:

Use of alternative dependent variables (tax loss estimates, CPI corruption index)

Subsample analysis by income group and governance quality

Exclusion of known secrecy jurisdictions

VIF tests to assess multicollinearity

Clustered standard errors to address heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation

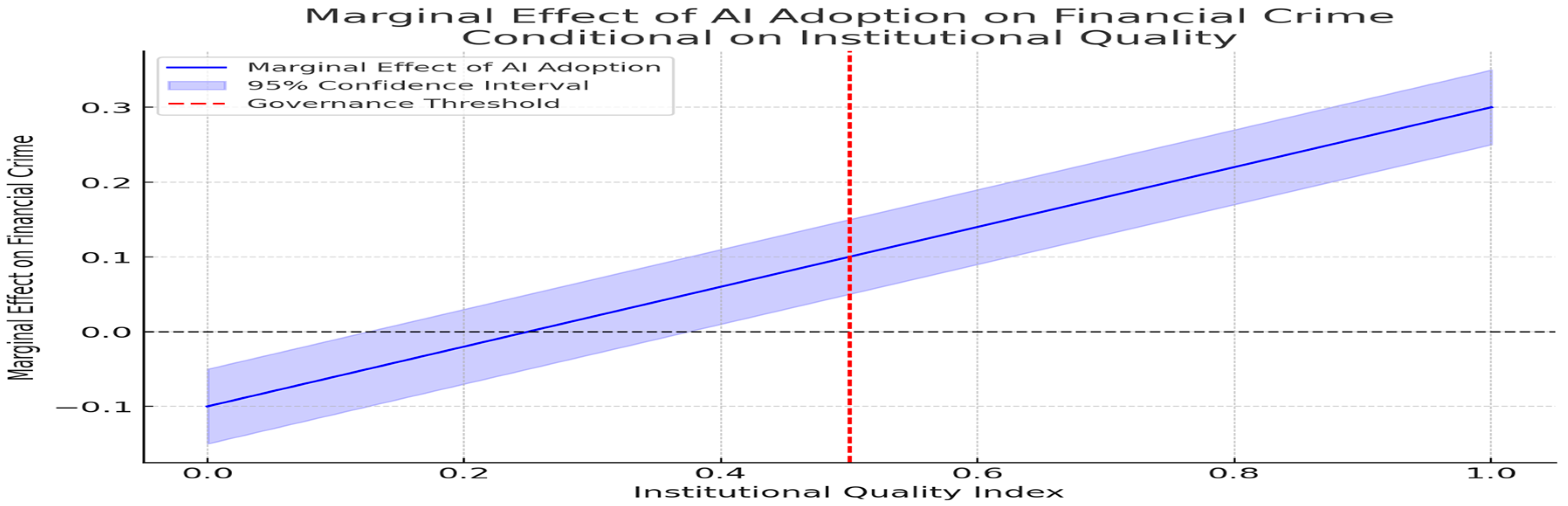

Interaction terms are plotted post-estimation to visualize marginal effects and test conditionality hypotheses.

3.6. Anticipated Contributions and Model Validity

This framework contributes to the literature by providing a refined lens on the policy relevance of AI. Unlike prior studies that treat AI as an exogenous policy lever, our model embeds it within the broader institutional context, allowing for more realistic causal interpretation. Diagnostic tests (e.g., first-stage F-statistics, VIFs, and Hausman tests) are integrated to affirm model consistency and internal validity.

4. Empirical Analysis and Discussion of Results

This chapter presents and contextualizes the econometric evidence derived from a balanced panel of 85 countries spanning the period from 2012 to 2023. All tables and figures are embedded within the discussion to facilitate interpretation and ensure analytical coherence with the theoretical framework.

4.1. Main Regression Results

The baseline fixed-effects panel regression results, shown in

Table 4, indicate a statistically significant negative association between the AI Adoption Index and key financial crime metrics. Specifically, a one-unit increase in AI adoption correlates with an estimated 2.5% decrease in illicit financial flows (β = -0.025, p = 0.006). Institutional quality also shows a strong negative relationship with financial crime (β = -0.031, p = 0.002), affirming longstanding theoretical expectations.

Crucially, the interaction term (AI × Institutional Quality) is both negative and statistically significant (β = -0.017, p = 0.034). This implies that the marginal effectiveness of AI in mitigating financial crime is conditional upon the quality of regulatory governance. In high-governance settings, AI amplifies crime-deterrent effects, whereas in weak institutional contexts, the benefits appear muted or even reversed.

To confirm the robustness of the fixed-effects and IV models, we conducted a series of diagnostic tests summarized in

Table 5.

4.2. Addressing Endogeneity: Instrumental Variable Approach

To mitigate potential endogeneity—where countries with higher exposure to financial crime might adopt AI technologies more aggressively—we apply a two-stage least squares (2SLS) model. Lagged national digital infrastructure investments and the presence of national AI procurement strategies serve as instruments.

Table 6 shows that the second-stage coefficients retain the expected signs and statistical significance. The coefficient on AI adoption remains negative (β = -0.029, p = 0.004), with a similarly significant interaction term. First-stage diagnostics confirm the instruments' relevance, with F-statistics above 10.

4.3. Robustness Checks and Subsample Analyses

Table 7 presents several robustness checks that support the internal validity of the findings. The results are robust to alternative dependent variables, such as CPI corruption scores and estimates of tax evasion losses. Subsample analyses show that the negative association between AI and financial crime is most pronounced in OECD and upper-middle-income economies.

Excluding secrecy jurisdictions enhances the effect size of AI coefficients, suggesting that financial opacity in tax havens can obscure global patterns. Variance inflation factor (VIF) scores remain below 5 for all variables, indicating the absence of multicollinearity.

4.4. Conditional Effects and Diagnostic Visuals

Figure 1 illustrates the marginal effect of AI adoption at different levels of institutional quality. The positive slope beyond the governance threshold confirms that AI’s crime-deterrent effect is amplified in high-integrity regulatory environments. In contrast, its effect is statistically indistinct in jurisdictions with weak governance structures.

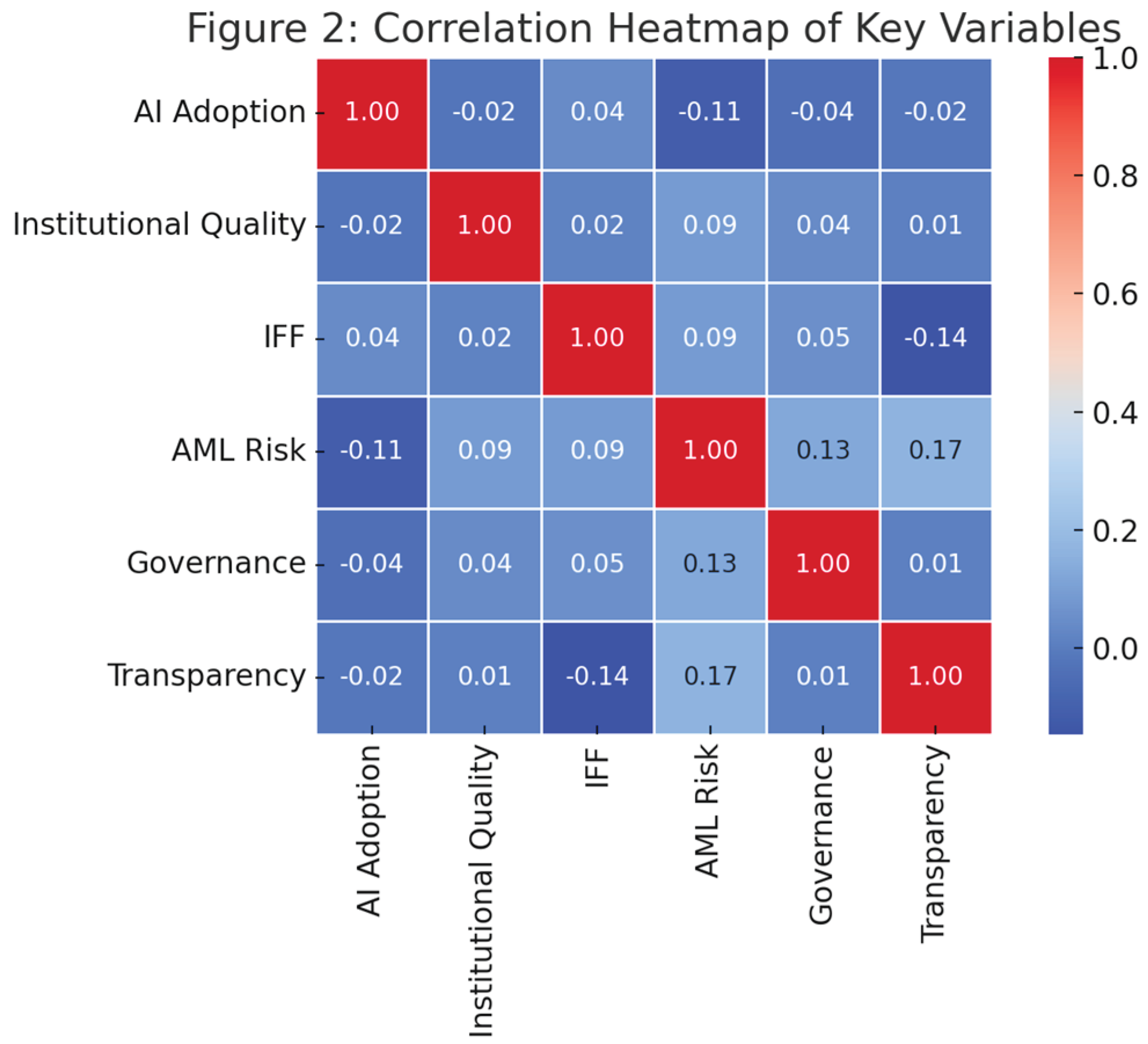

Complementing this,

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation matrix among the key independent variables. Moderate correlations are observed, with the highest (between AI Adoption and GDP per capita) at 0.58. These results confirm the model's suitability and the lack of severe multicollinearity.

5. Ethical and Operational Limitations

Despite its promise in regulatory oversight and enforcement, artificial intelligence (AI) raises fundamental questions that must be addressed. These difficulties are even more pronounced in cross-border financial crime control; the gaps between regulatory abilities and institutional transparency may exacerbate systemic deficits.

5.1. Ethical Risks of AI Deployment in Financial Crime Regulation

One of the most pressing ethical concerns is the fear that AIs may infringe on personal rights, including privacy, fairness, and due process. These AI-driven surveillance tools, particularly those designed for financial profiling and behavioral monitoring, often rely on historical data that can reflect existing societal or institutional biases. This reliance may result in unfair discrimination against specific geographies, classes, or transaction profiles, thereby perpetuating a cycle of baseless discriminatory sanctions or blacklists.

Furthermore, the black box problem complicates matters further: many advanced AI models are opaque. Regulators may be technically unequipped to question algorithmic decision-making, and as a result, transparency and recourse mechanisms can be compromised. If an AI model misses a critical case of financial fraud or incorrectly flags a benign activity, the uncertainty surrounding liability for the regulator, the model developer, and the provider of lending or trading data has significant implications for governance.

5.2. Operational Constraints Across Jurisdictions

AI systems require robust digital infrastructure, high-quality datasets, and skilled personnel to function effectively. Many low- and middle-income countries suffer from gaps in one or more of these areas, making them less capable of integrating AI into their financial oversight regimes. This infrastructural asymmetry creates uneven enforcement capabilities, effectively offering havens for financial criminals who exploit these disparities.

Moreover, many regulators rely on third-party vendors for AI systems, lacking in-house capabilities to validate, interpret, or maintain these technologies. Such dependencies create vulnerabilities to external influence and further complicate cross-border regulatory cooperation.

5.3. Data Quality and Algorithmic Governance

Reliable data is the “backbone of successful AI technology”. Yet, a large number of regions lack standardized, interoperable, and well-understood datasets on which to train and validate regulatory AI models. Without effective data governance (DG), AI outputs can include irregularities, empty values, or systemic noise, leading to incorrect classifications or the overlooking of anomalies. Institutional protection mechanisms would be needed to mitigate these risks.

These include:

Independent algorithmic reviews to evaluate fairness, accountability, and performance outcomes.

Explainability requirement: Commitment to relatively stringent, mandatory explainability to ensure interpretability of model output

Ethics review boards to monitor how AI systems are used and the impact they have

Ultimately, technology cannot replace institutional integrity. Instead, the approach should focus on augmenting human judgment within the context of transparent, accountable, and well-resourced governance. The effectiveness of AI in financial crime policing depends not only on technical capability but also on the responsible embedding in an ethical and institutional environment.

6. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

This research examines the conduct of financial crime by AI, which acts as both a deterrent and a facilitator, depending critically on the institutional context within which it is used. Leveraging a panel dataset of 85 countries ranging from 2012 to 2023, the paper employs fixed-effects models and instrumental variable methods to examine whether AI may contribute to containing financial crime in the presence of strong governance structures.

The results suggest a strong link between AI adaptation and reduced flows of illicit finances, as well as improved anti-money laundering (AML) risk evaluations, particularly among nations with high levels of institutional quality and transparency. But not everyone enjoys those advantages. In jurisdictions with poor governance or enforcement, AI may lead to no improvement in performance, or it may enhance the sophistication of regulatory avoidance.

These findings have important policy implications. Simply incorporating AI technologies is not sufficient. That’s only effective if it’s rooted in institutions that are competent, accountable, and transparent. From this perspective, AI should be a complement to strong governance and not its substitute. A combined effort by national authorities, international financial institutions and regulatory authorities is needed. These should aim to:

Creating standards that can be adopted for AI integration into compliance frameworks

Algorithmic transparency, enforcement, and explainability

Support institutional strengthening, especially in low-income areas

Enhance data sharing, standardization, and accountability across borders.

There are also moral issues that should be addressed. Fairness and Integrity in Financial Regulation: AI algorithms must be built with antidiscrimination guardrails, robust privacy protocols, and auditable standards for their development and deployment, thereby enabling their innovation and responsible use.

As we advance, we require further research to comprehend how AI operates in specific financial contexts. Topics, including but not limited to surveillance of cryptocurrency transactions, identification of beneficial ownership, and development of forensic accounting capabilities, represent promising areas for exploration. The development and testing of AI-enabled real-time network analysis tools would also yield essential knowledge on digital technologies innovation in global finance surveillance. In conclusion, there is great promise for AI in combating financial crime. But its efficacy will depend on whether it is utilized by systems that prioritize transparency, fairness, and institutional legitimacy. The question for policymakers is not merely the adoption of AI, but the adoption of AI in a manner that bolsters — rather than undermines — the legitimacy of financial governance.

Appendix A. List of 85 Countries Included in the Study

Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea (Republic of), Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

References

- Al Qudah, A. (2024). Unveiling the shadow economy: A comprehensive review of corruption dynamics and countermeasures. Kurdish Studies, 12(2), 4768-4784.

- Arner, D. W., Zetzsche, D. A., Buckley, R. P., & Kirkwood, J. M. (2024). The financialisation of Crypto: Designing an international regulatory consensus. Computer Law & Security Review, 53, 105970. [CrossRef]

- Binns, R. (2018). Algorithmic accountability and public reason. Philosophy & technology, 31(4), 543-556. [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, M., Kaal, W. A., & Vermeulen, E. P. (2016). Regulation tomorrow: what happens when technology is faster than the law. Am. U. Bus. L. Rev., 6, 561.

- Feyen, E., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., Natarajan, H., & Saal, M. (2021). Fintech and the digital transformation of financial services: implications for market structure and public policy. BIS papers.

- Levi, M. (2020). Evaluating the control of money laundering and its underlying offences: the search for meaningful data. Asian Journal of Criminology, 15(4), 301-320. [CrossRef]

- Mestikou, M., Smeti, K., & Hachaïchi, Y. (2023). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in financial services market developments and financial stability implications. Financial Stability Board, 1, 1-6.

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press.

- Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

- Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of economic growth, 9, 131-165. [CrossRef]

- Sharman, J. C. (2011). The money laundry: Regulating criminal finance in the global economy. Cornell University Press.

- Tran, T. T. H., & Rose, G. (2022). The legal framework for prosecution of money laundering offences in Vietnam. Austl. J. Asian L., 22, 35.

- Udayakumar, R., Joshi, A., Boomiga, S., & Sugumar, R. (2023). Deep fraud Net: A deep learning approach for cyber security and financial fraud detection and classification. Journal of Internet Services and Information Security, 13(3), 138-157.

- Wachter, S., & Mittelstadt, B. (2019). A right to reasonable inferences: re-thinking data protection law in the age of big data and AI. Colum. Bus. L. Rev., 494.

- Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). Decentralized finance. Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 172-203.

- Zuboff, S. (2023). The age of surveillance capitalism. In Social theory re-wired (pp. 203-213). Routledge.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).