Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

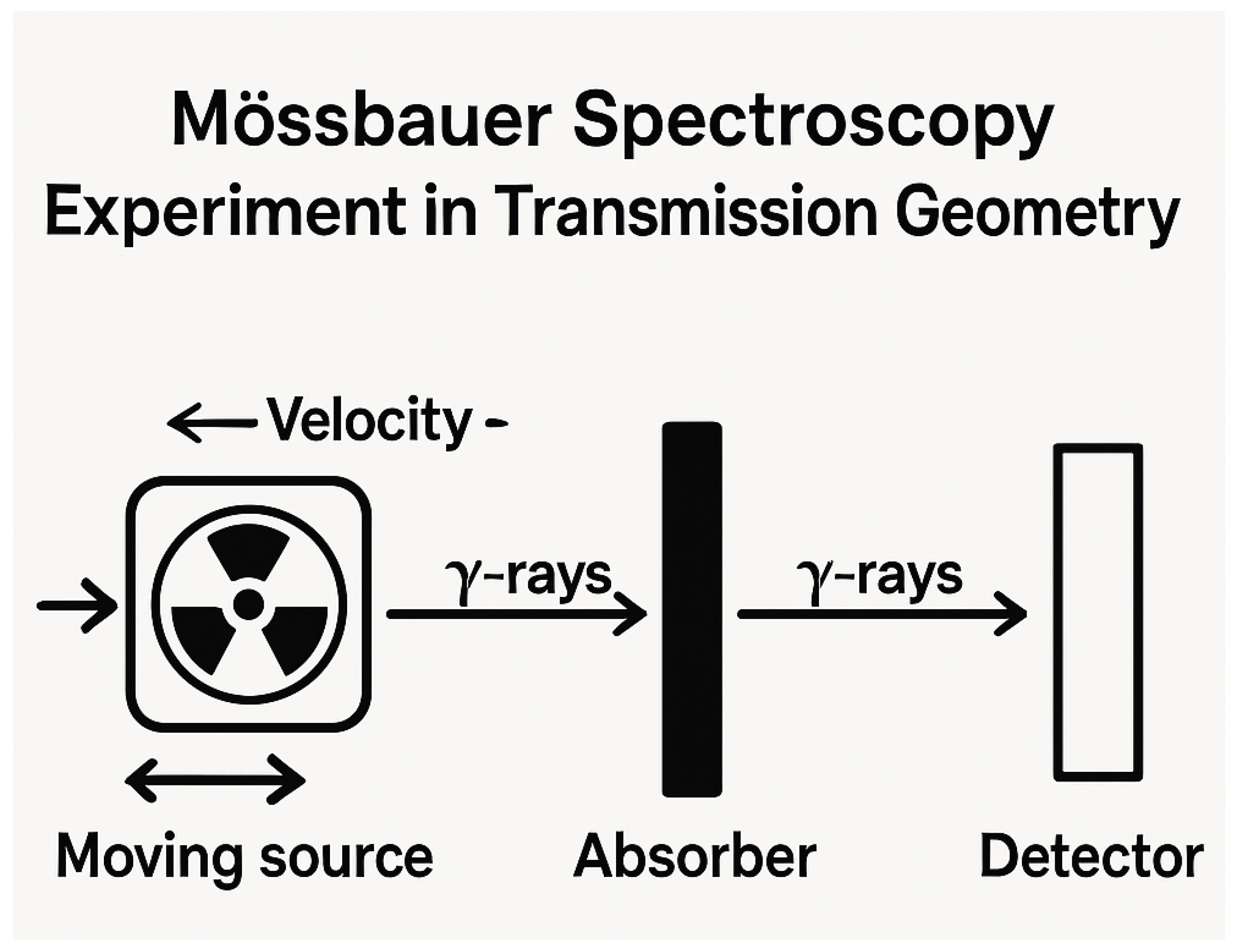

1. Introduction

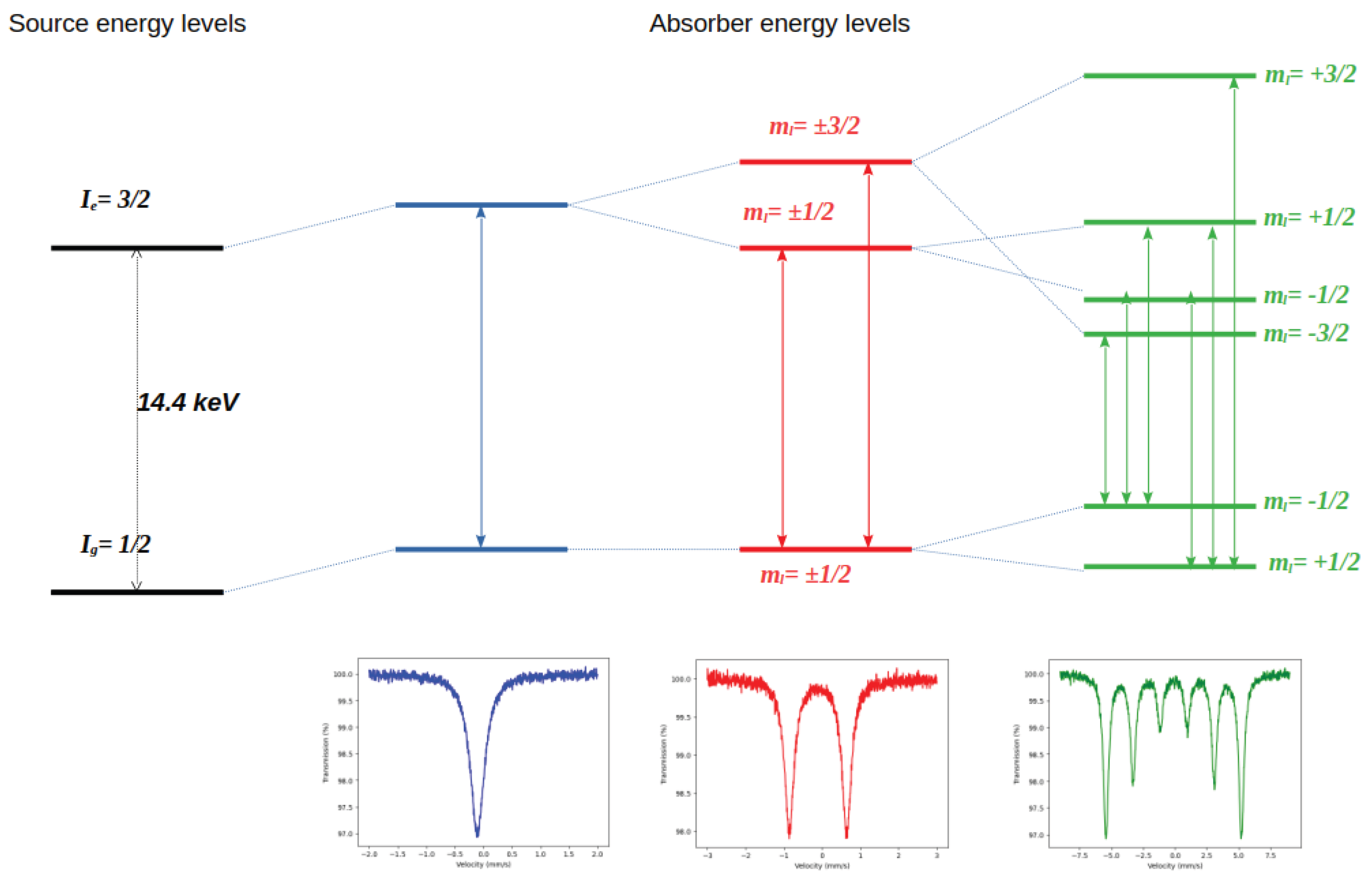

1.1. Isomer Shift, or

1.2. Quadrupole Splitting, or

1.3. Magnetic Hyperfine Field,

1.4. Statement of Need

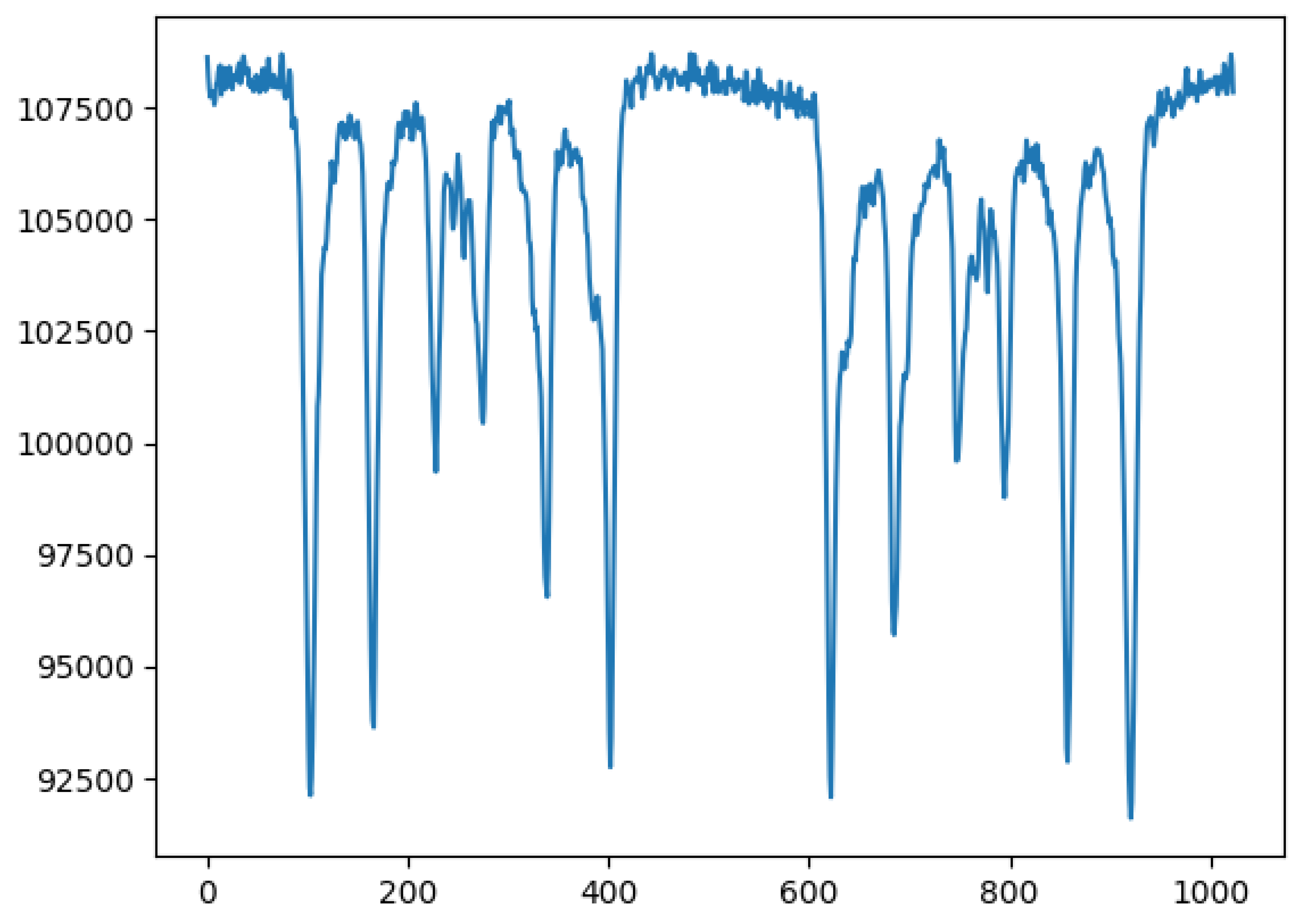

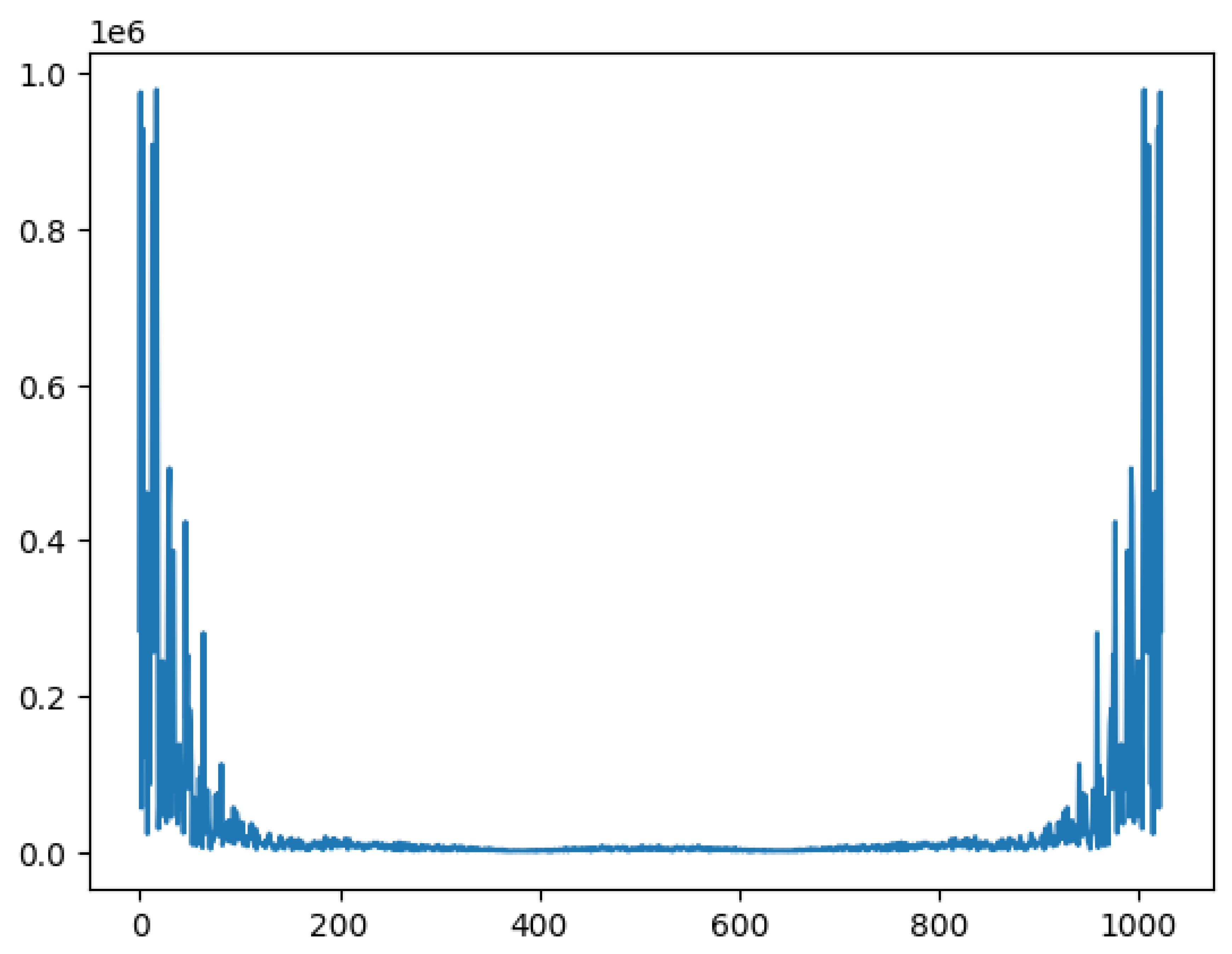

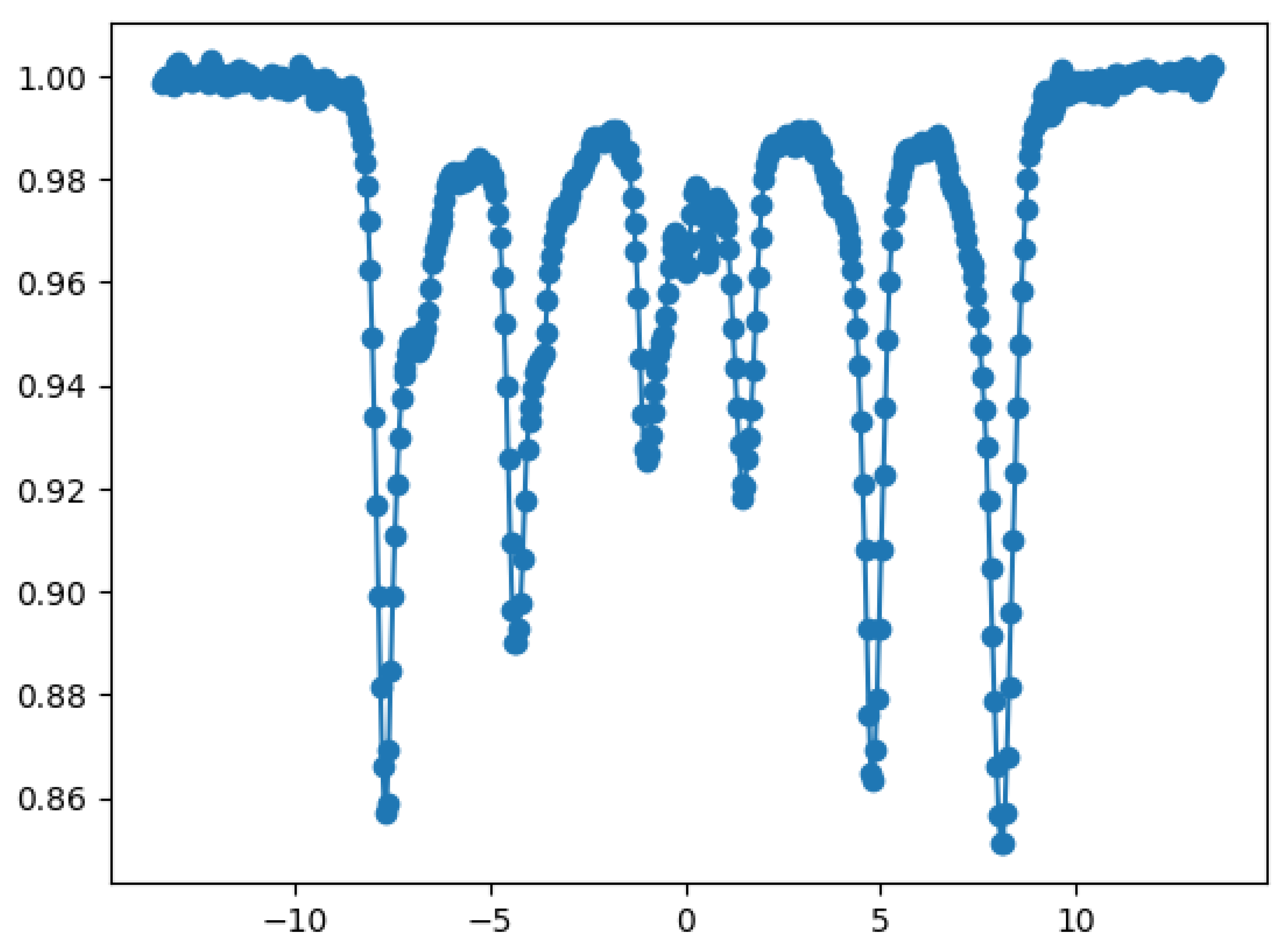

2. Mössbauer Spectra and Curve Shapes

2.1. Curve Fitting and Least Squares Method

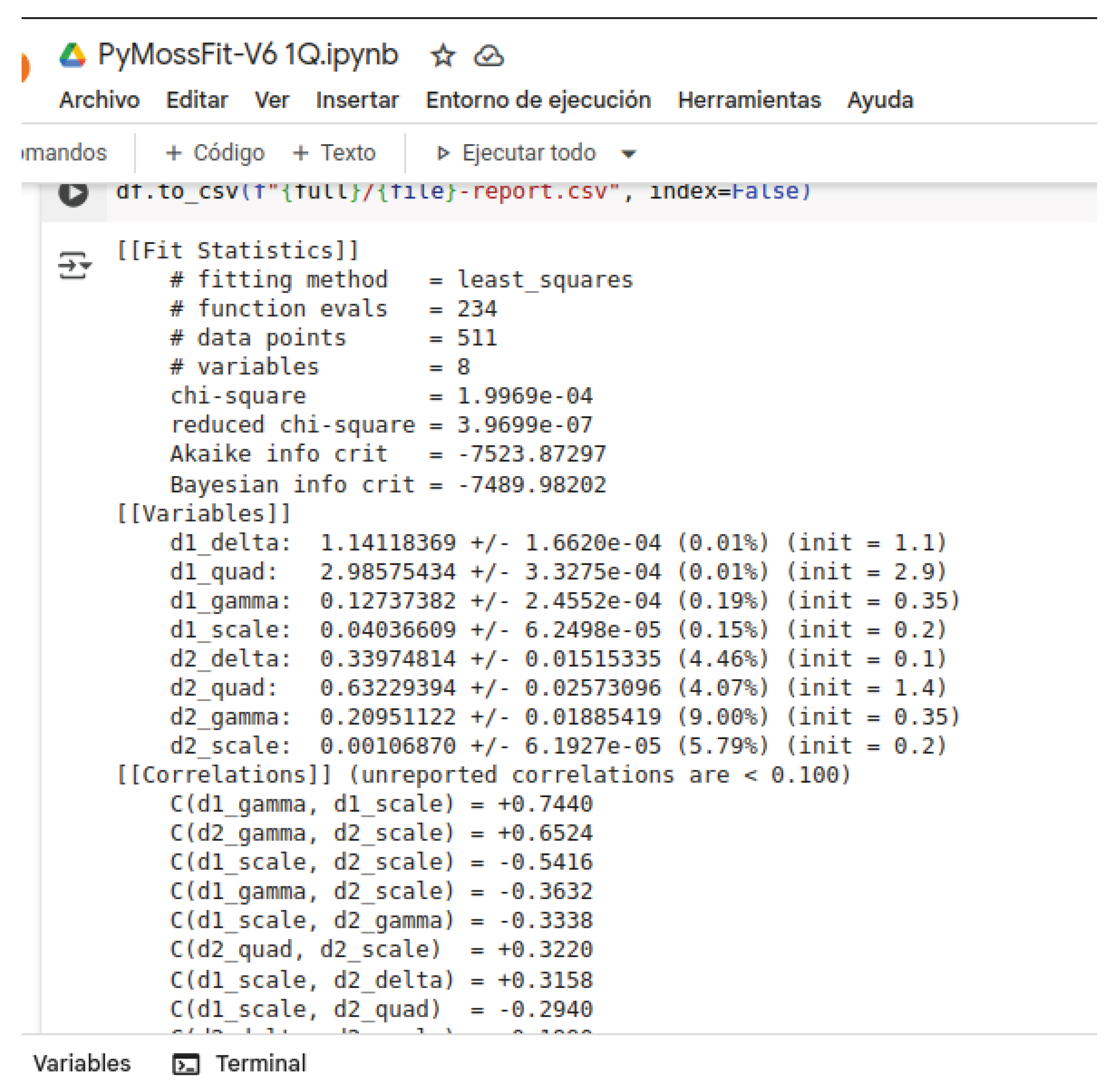

3. Description of the Python code for Google Colab (PyMossFit)

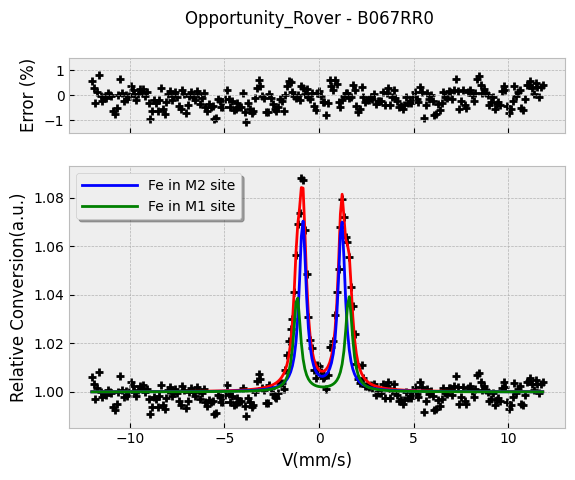

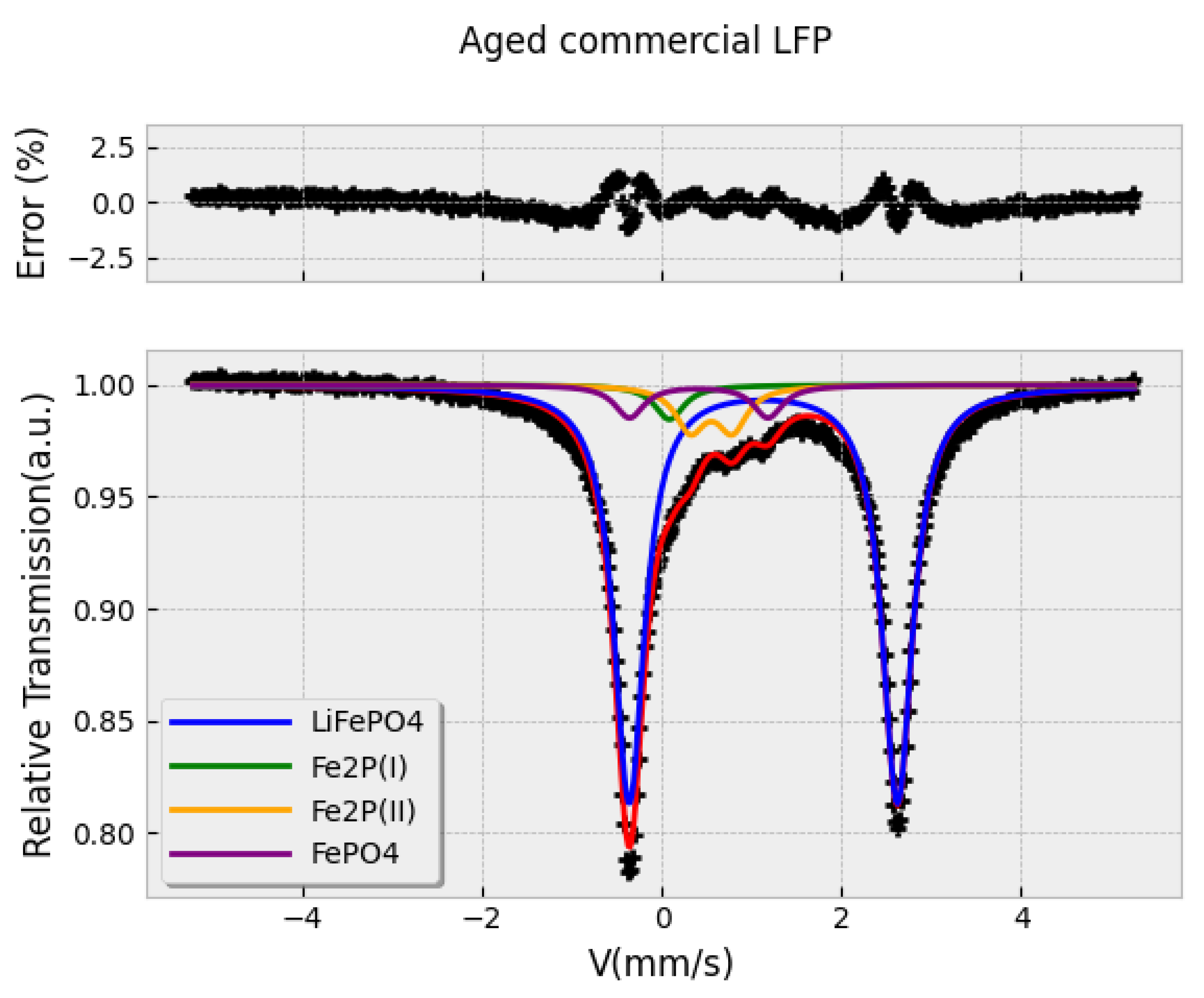

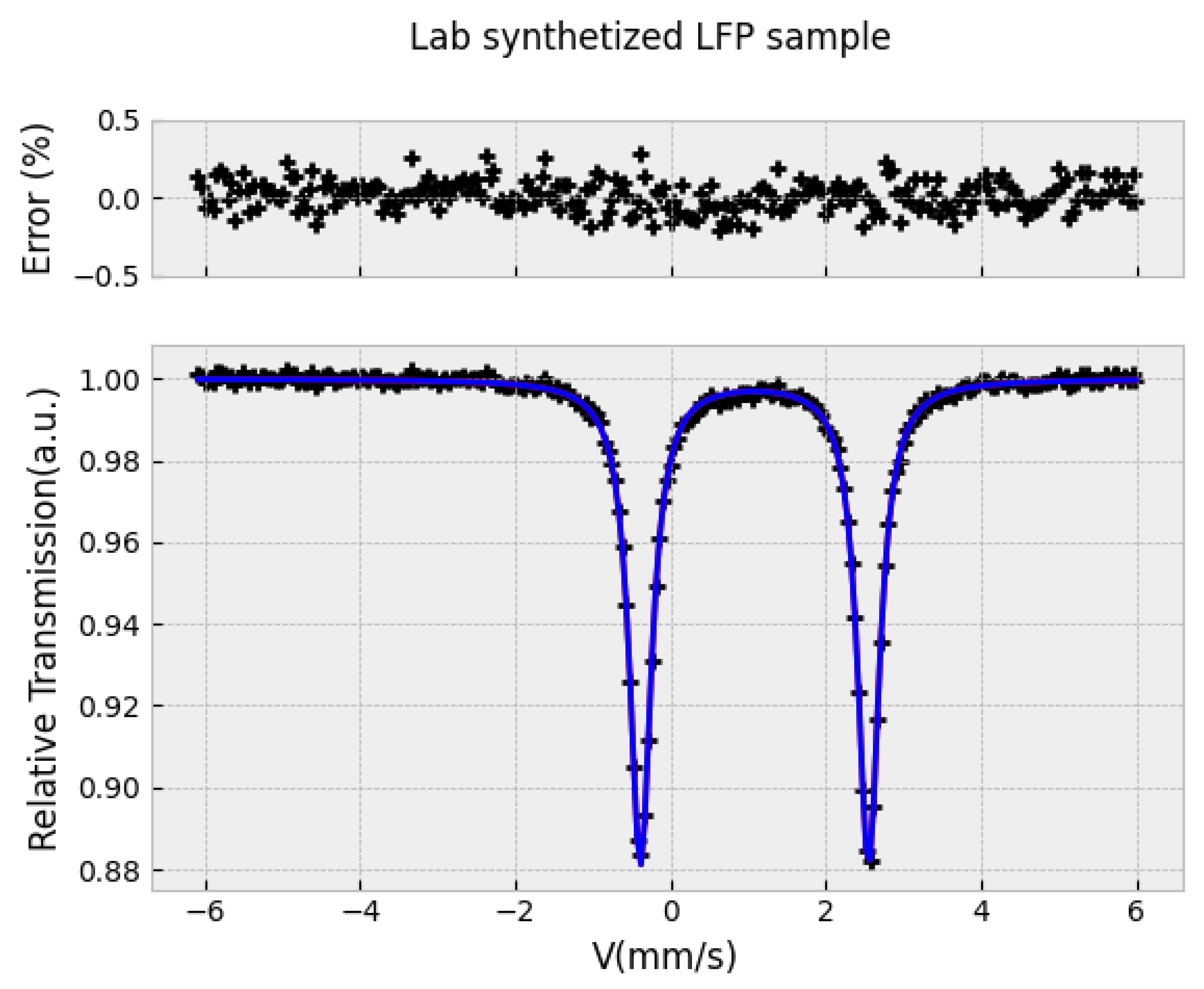

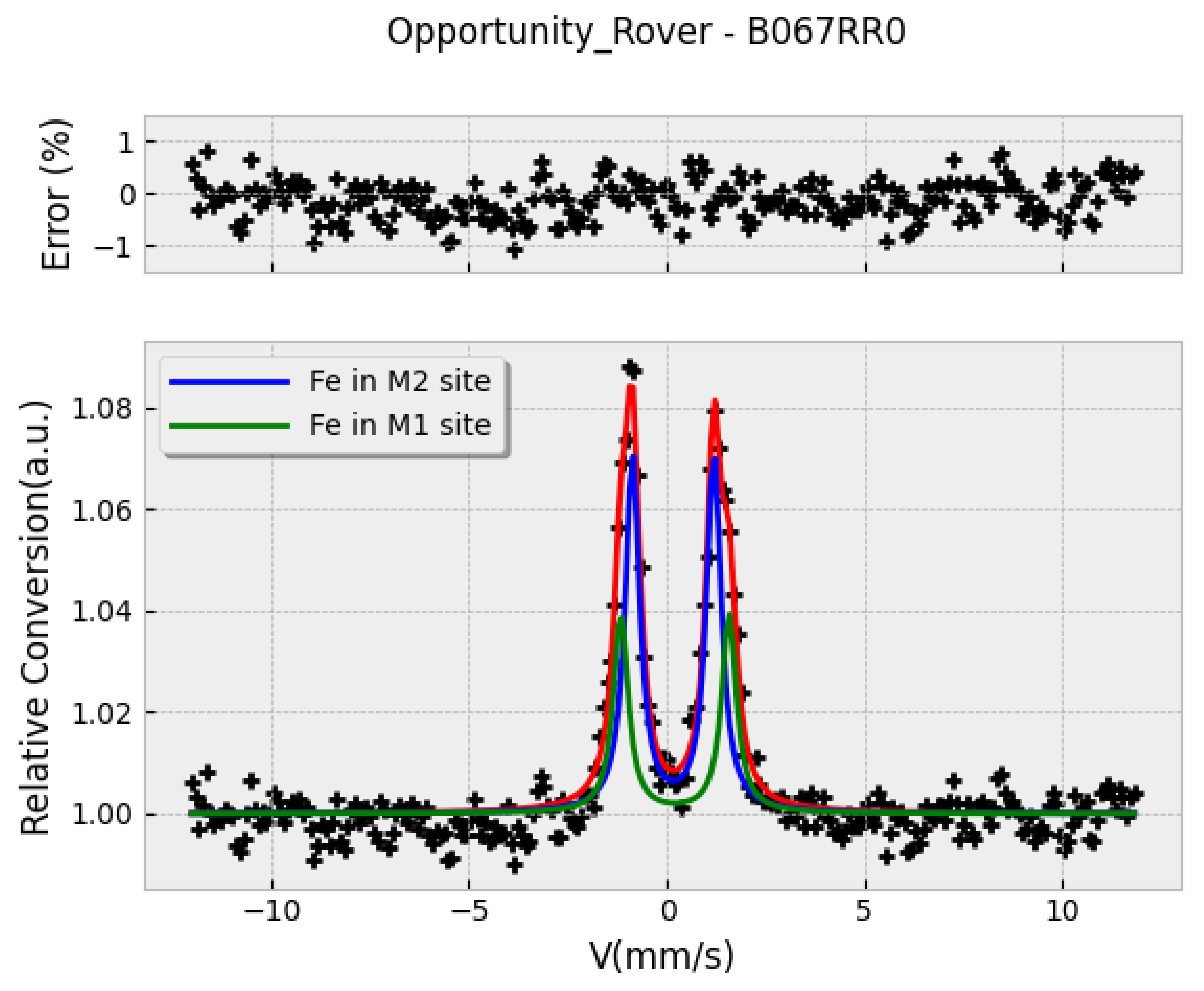

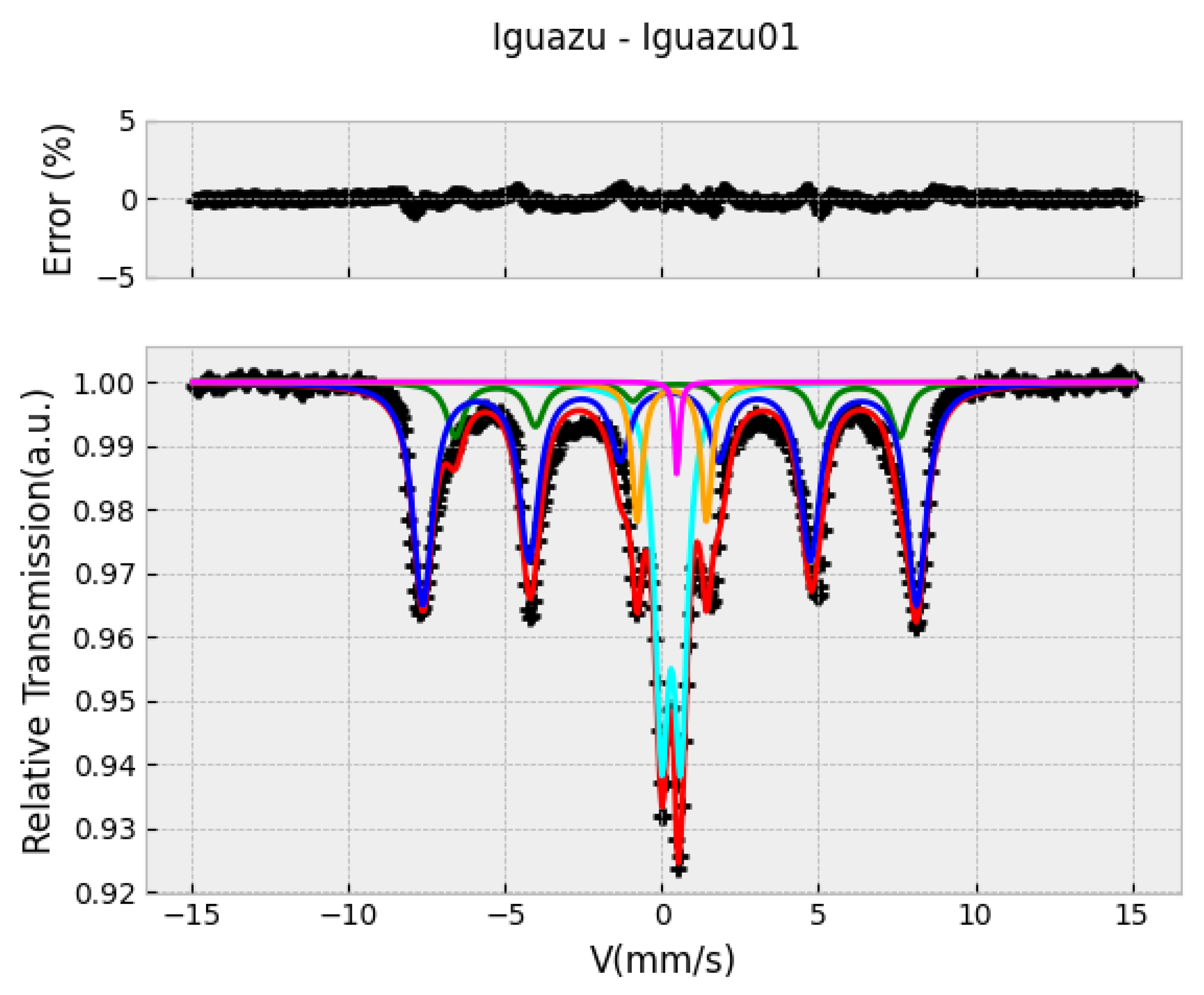

3.1. Some Examples

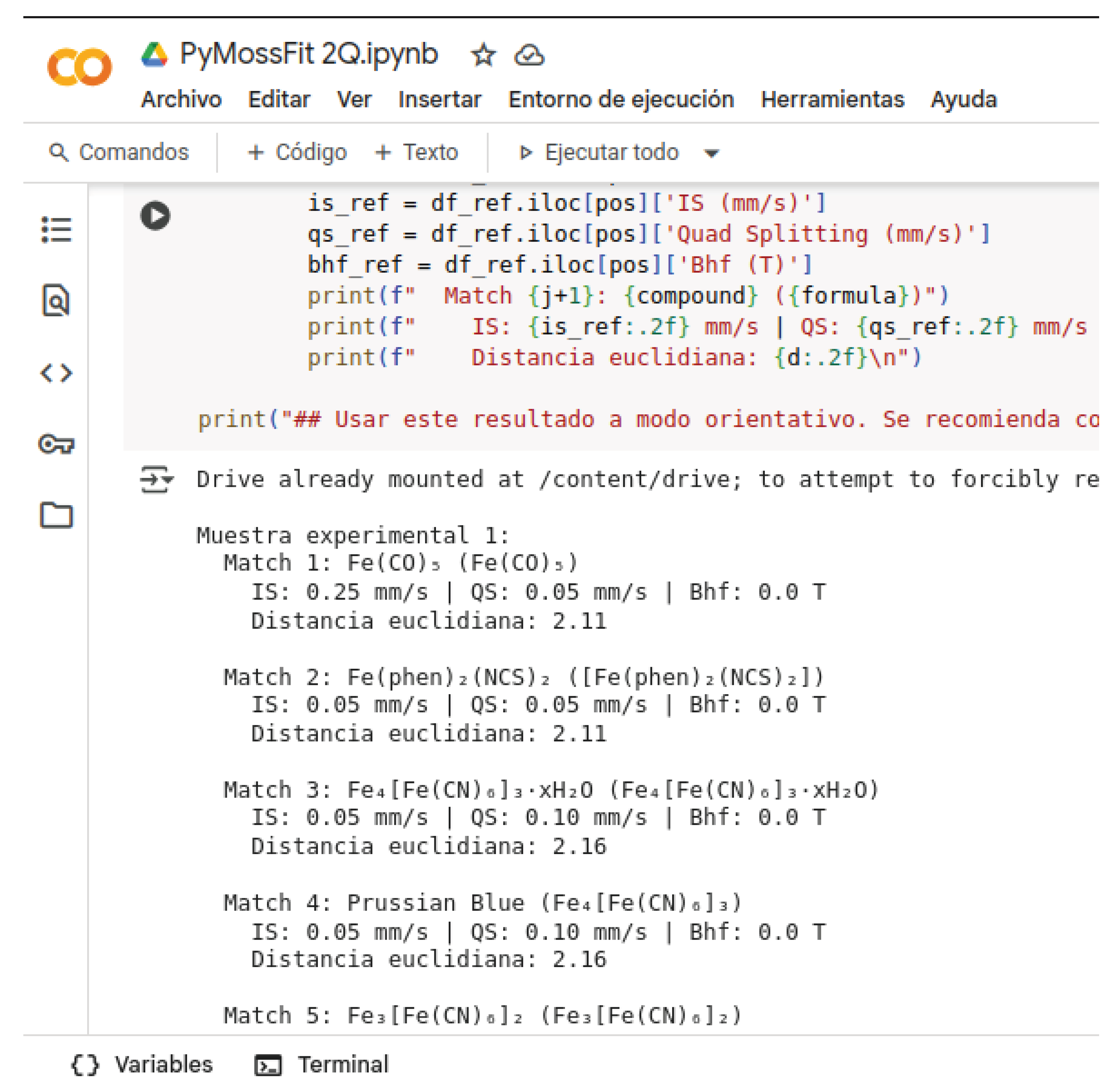

3.2. Match of Fitted Parameters with a Local Database

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Wikipedia contributors. Mössbauer spectroscopy — Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2025. [Online; accessed 19-June-2025].

- Tao, W.; Junhu, Z. The Mössbauer Effect Data Center.

- Martinho, M.; Münck, E., 57Fe Mössbauer Spectroscopy in Chemistry and Biology. In Physical Inorganic Chemistry; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 2010; chapter 2, pp. 39–67, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470602539.ch2]. [CrossRef]

- Dyar, M.D.; Agresti, D.G.; Schaefer, M.W.; Grant, C.A.; Sklute, E.C. MÖSSBAUER SPECTROSCOPY OF EARTH AND PLANETARY MATERIALS. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2006, 34, 83–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H. A Mössbauer scheme to probe gravitational waves. Science Bulletin 2024, 69, 2795–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.R.; Wertheim, G.K.; Jaccarino, V. Interpretation of the Fe57 Isomer Shift. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1961, 6, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-Long, C.; De-Ping, Y., Synchrotron Mössbauer Spectroscopy. In Mössbauer Effect in Lattice Dynamics; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 2007; chapter 7, pp. 253–304, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9783527611423.ch7]. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, F.; Long, G.J. Best Practices and Protocols in Mössbauer Spectroscopy. Chemistry of Materials 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarec, K.; Rancourt, D.G. RECOIL, Mössbauer Spectral Analysis Software for Windows (Version 1.0), 1998.

- Newville, M.e.a. LMFIT: Non-Linear Least-Squares Minimization and Curve-Fitting for Python (version 1.3.4).

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saccone, F.D. Fitting code for Mössbauer Spectroscopy running in Jupyter Colab, 2025.

- Kong, Q.; Siauw, T.; Bayen, A. Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), 2020.

- Ferrari, S.; Apehesteguy, J.C.; Saccone, F.D. Structural and magnetic properties of Zn doped magnetite nanoparticles obtained by wet chemical method. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2015, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opportunity (MERB) Analyst’s Notebook, 2025.

- Corke, P.; Haviland, J. Mössbauer mineralogy of rock, soil, and dust at Meridiani Planum, Mars: Opportunity’s journey across sulfate-rich outcrop, basaltic sand and dust, and hematite lag deposits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2006, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Oshtrakh, M.I.; Petrova, E.; Grokhovsky, V. Determination of quadrupole splitting for 57Fe in M1 and M2 sites of both olivine and pyroxene in ordinary chondrites using Mössbauer spectroscopy with high velocity resolution. Hyperfine Interactions 2007, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Junhu, Z. Mössbauer Effect Data Reference Journal.

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).