Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

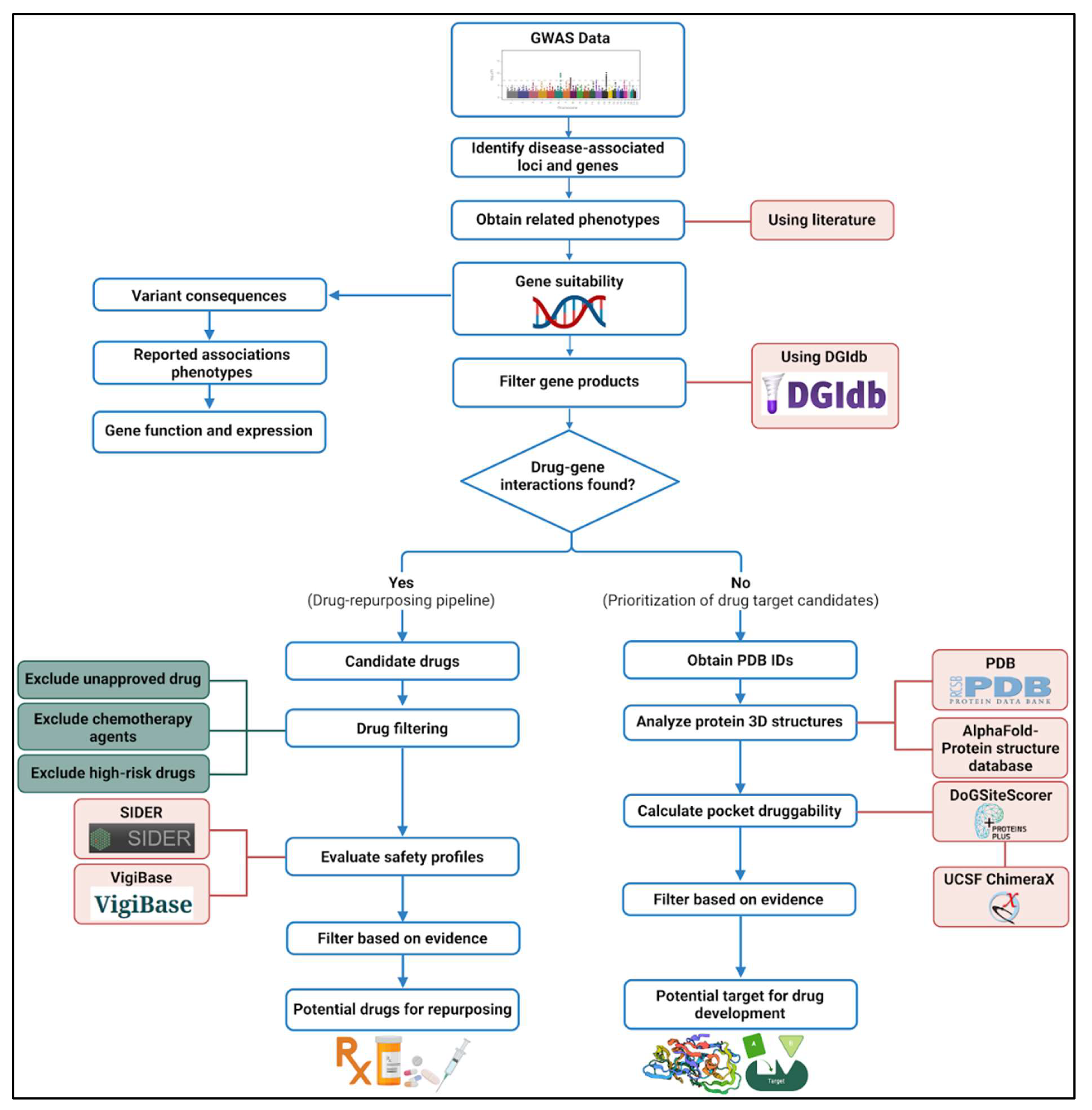

2.1. The Pipeline for Drug Repurposing and Novel Drug Development

2.2. Selection of SCD Severity-Associated Genes

2.3. Drug-Gene Interaction Analysis for Drug Repurposing

2.4. Novel Drug Development Pipeline

3. Results

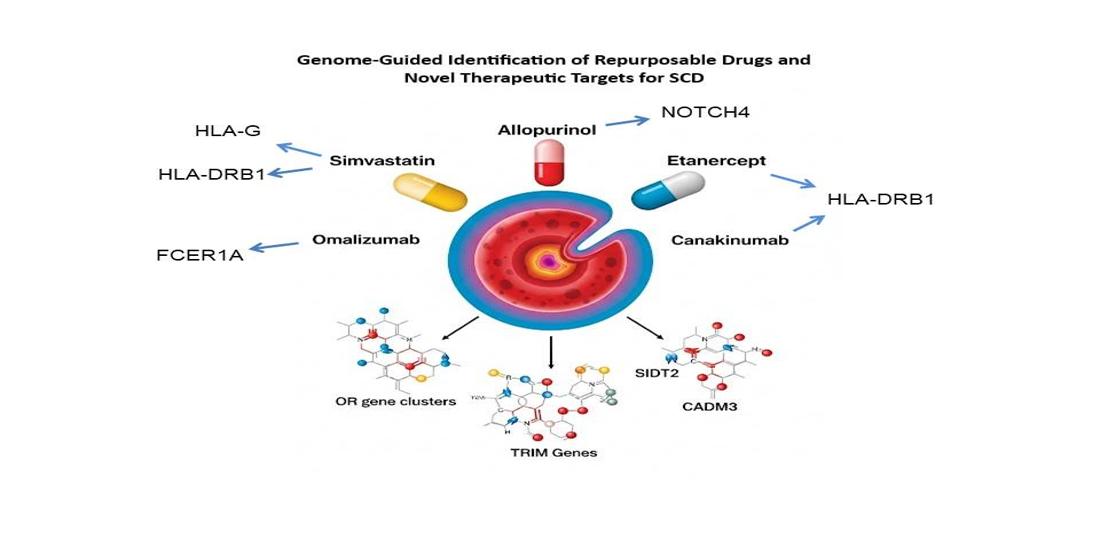

3.1. Promising Candidates for Drug Repurposing

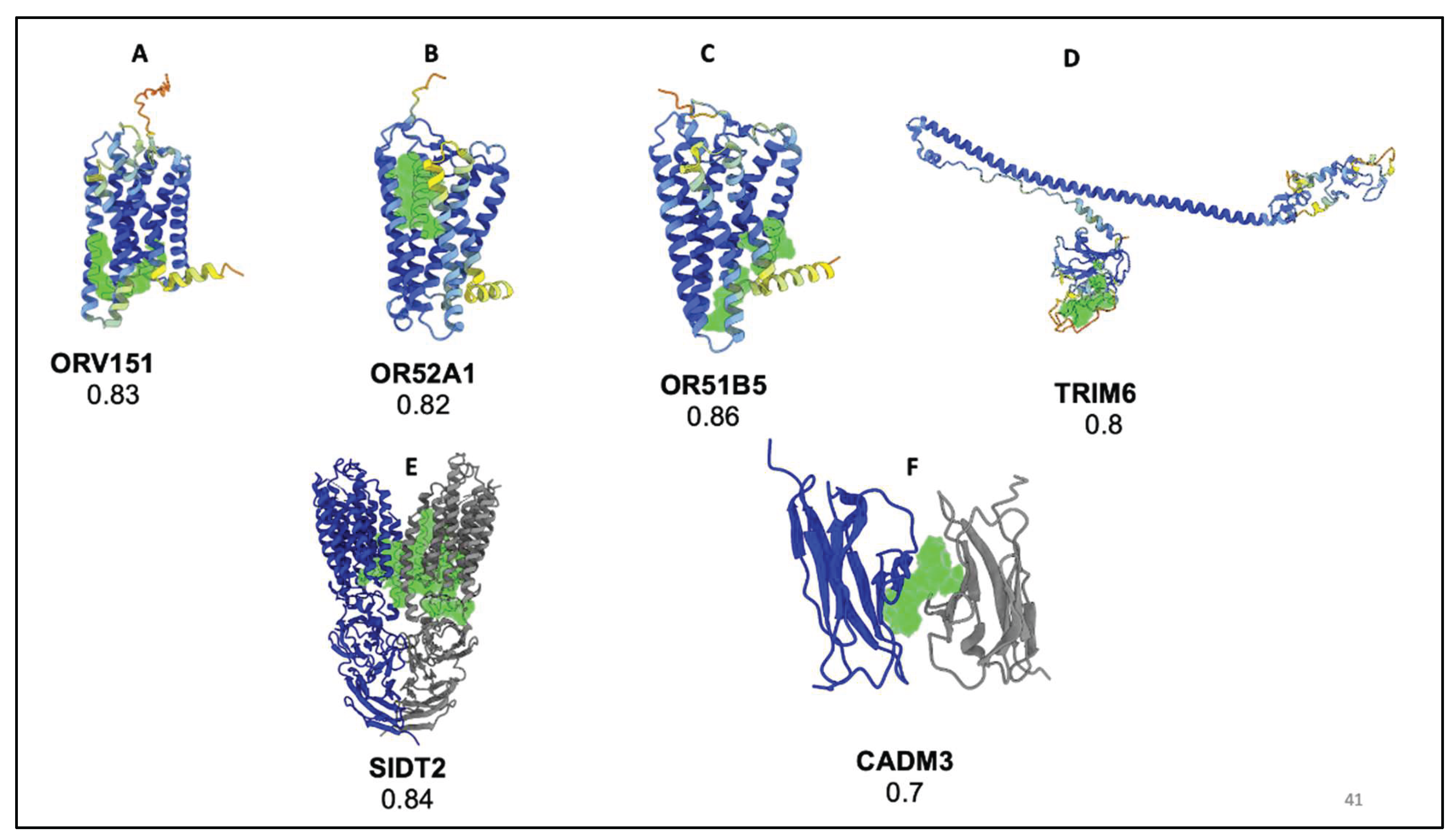

3.2. Druggability Analysis of Non-Targeted Loci

4. Discussion

3.5. Limitation

3.6. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Authors’ contribution

Funding

Conflict of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Inusa BPD, Hsu LL, Kohli N, et al. Sickle Cell Disease-Genetics, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisário AR, Silva CM, Velloso-Rodrigues C, Viana MB. Genetic, laboratory and clinical risk factors in the development of overt ischemic stroke in children with sickle cell disease. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2018, 40, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnodu OE, Oron AP, Sopekan A, Akaba GO, Piel FB, Chao DL. Child mortality from sickle cell disease in Nigeria: a model-estimated, population-level analysis of data from the 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e723–e731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware RE, de Montalembert M, Tshilolo L, Abboud MR. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2017, 390, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastaniah, W. Epidemiology of sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2011, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Zuair A, Aldossari S, Alhumaidi R, Alrabiah M, Alshabanat A. The Burden of Sickle Cell Disease in Saudi Arabia: A Single-Institution Large Retrospective Study. Int J Gen Med. 2023, 16, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Hazmi MA, al-Swailem AR, Warsy AS, al-Swailem AM, Sulaimani R, al-Meshari AA. Consanguinity among the Saudi Arabian population. J Med Genet. 1995, 32, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh PL, Fasipe TA, Wun T. Sickle Cell Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2022, 328, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas Cisneros G, Thein SL. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Voluntarily Withdraws All Lots of Sickle Cell Disease Treatment OXBRYTA® (voxelotor) From Worldwide Markets | Pfizer. Available online: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-voluntarily-withdraws-all-lots-sickle-cell-disease (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Revocation of authorisation for sickle cell disease medicine Adakveo | European Medicines Agency (EMA). May 26, 2023. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/revocation-authorisation-sickle-cell-disease-medicine-adakveo (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Commissioner O of the. FDA Approves First Gene Therapies to Treat Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. FDA. August 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapies-treat-patients-sickle-cell-disease (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Burt T, Dhillon S. Pharmacogenomics in early-phase clinical development. Pharmacogenomics. 2013, 14, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghubayshi A, Wijesinghe D, Alwadaani D, et al. Unraveling the Complex Genomic Interplay of Sickle Cell Disease Among the Saudi Population: A Case-Control GWAS Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragante V, Hemerich D, Alshabeeb M, et al. Druggability of Coronary Artery Disease Risk Loci. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018, 11, e001977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom, S. Introduction and Historical Overview of Drug Repurposing Opportunities. Available online: https://books.rsc.org/books/edited-volume/1885/chapter/2472263/Introduction-and-Historical-Overview-of-Drug (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Kirkham JK, Estepp JH, Weiss MJ, Rashkin SR. Genetic Variation and Sickle Cell Disease Severity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2337484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincez T, Ashley-Koch AE, Lettre G, Telen MJ. Genetic Modifiers of Sickle Cell Disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2022, 36, 1097–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page GP, Kanias T, Guo YJ, et al. Multiple-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci associated with measures of hemolysis following blood storage. J Clin Invest. 2021, 131, e146077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard JLE, O’Mara TA, Glubb DM. Enhancing the Promise of Drug Repositioning through Genetics. Front Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metaferia B, Cellmer T, Dunkelberger EB, et al. Phenotypic screening of the ReFRAME drug repurposing library to discover new drugs for treating sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022, 119, e2210779119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu PC, Afiukwa CA, Orji OU, et al. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telen MJ, Malik P, Vercellotti GM. Therapeutic strategies for sickle cell disease: towards a multi-agent approach. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabeeb MA, Alwadaani D, Al Qahtani FH, et al. Impact of Genetic Variations on Thromboembolic Risk in Saudis with Sickle Cell Disease. Genes (Basel). 2023, 14, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driss A, Asare KO, Hibbert JM, Gee BE, Adamkiewicz TV, Stiles JK. Sickle Cell Disease in the Post Genomic Era: A Monogenic Disease with a Polygenic Phenotype. Genomics Insights. 2009, 2009, 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Stevenson J, Stahl K, et al. DGIdb 5.0: rebuilding the drug-gene interaction database for precision medicine and drug discovery platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1227–D1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VigiAccess. Available online: https://www.vigiaccess.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Kuhn M, Letunic I, Jensen LJ, Bork P. The SIDER database of drugs and side effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn M, Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Bork P. STITCH 3: zooming in on protein-chemical interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bever E, Wirtz VJ, Azermai M, et al. Operational rules for the implementation of INN prescribing. Int J Med Inform. 2014, 83, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkamer A, Kuhn D, Rippmann F, Rarey M. DoGSiteScorer: a web server for automatic binding site prediction, analysis and druggability assessment. Bioinformatics. 2012, 28, 2074–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): ensuring a single, uniform archive of PDB data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. Chemistry Nobel goes to developers of AlphaFold AI that predicts protein structures. Nature. 2024, 634, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Home - GEO - NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- GTEx Portal. Available online: https://www.gtexportal.org/home/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Kirkham JK, Estepp JH, Weiss MJ, Rashkin SR. Genetic Variation and Sickle Cell Disease Severity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2337484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang H, Pan S, Lin S, Wang YY, Yuan N, Jia P. PharmGWAS: a GWAS-based knowledgebase for drug repurposing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D972–D979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa D, Karim M, Ghoussaini M, Hulcoop DG, McDonagh EM, Dunham I. Human genetics evidence supports two-thirds of the 2021 FDA-approved drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A. Perspective Chapter: Technological Advances in Population Genetics. IntechOpen; 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ku CS, Loy EY, Pawitan Y, Chia KS. The pursuit of genome-wide association studies: where are we now? J Hum Genet. 2010, 55, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reay WR, Cairns MJ. Advancing the use of genome-wide association studies for drug repurposing. Nat Rev Genet. 2021, 22, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug Repurposing (DR): An Emerging Approach in Drug Discovery | IntechOpen. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/72744 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Nanda H, Ponnusamy N, Odumpatta R, Jeyakanthan J, Mohanapriya A. Exploring genetic targets of psoriasis using genome wide association studies (GWAS) for drug repurposing. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Mao C, Hou Y, et al. Interpretable deep learning translation of GWAS and multi-omics findings to identify pathobiology and drug repurposing in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury FA, Colussi N, Sharma M, et al. Fatty acid nitroalkenes - Multi-target agents for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam SS, Hoppe C. Potential role for statins in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013, 60, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereal-Williams C, Machado RF, McGowan V, et al. Atorvastatin reduces serum cholesterol and triglycerides with limited improvement in vascular function in adults with sickle cell anemia. Haematologica. 2012, 97, 1768–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, et al. Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong K, Lai WK, Jackson DE. HLA Class II regulation of immune response in sickle cell disease patients: Susceptibility to red blood cell alloimmunization (systematic review and meta-analysis). Vox Sang. 2022, 117, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamouza R, Neonato MG, Busson M, et al. Infectious complications in sickle cell disease are influenced by HLA class II alleles. Hum Immunol. 2002, 63, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi N, Al-Ola K, Al-Subaie AM, et al. HLA class II haplotypes distinctly associated with vaso-occlusion in children with sickle cell disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins JO, Pagani F, Dezan MR, et al. Impact of HLA-G +3142C>G on the development of antibodies to blood group systems other than the Rh and Kell among sensitized patients with sickle cell disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 2022, 61, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaba K, Nwogoh B, Oshatuyi O. Determination of von Willebrand factor level in patient with sickle cell diseasein vaso-occlusive crisis. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020, 4, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar A, Serban C, Ursoniu S, et al. The impact of statin therapy on plasma levels of von Willebrand factor antigen. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Thromb Haemost. 2016, 115, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe C, Kuypers F, Larkin S, Hagar W, Vichinsky E, Styles L. A pilot study of the short-term use of simvastatin in sickle cell disease: effects on markers of vascular dysfunction. Br J Haematol. 2011, 153, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe C, Jacob E, Styles L, Kuypers F, Larkin S, Vichinsky E. Simvastatin reduces vaso-occlusive pain in sickle cell anaemia: a pilot efficacy trial. Br J Haematol. 2017, 177, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi C, Palani C, Takezaki M, et al. Simvastatin-Mediated Nrf2 Activation Induces Fetal Hemoglobin and Antioxidant Enzyme Expression to Ameliorate the Phenotype of Sickle Cell Disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López S, Romero de Ávila MJ, Hernández de León NC, et al. NOTCH4 Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Activated Macrophages by Interfering With Interferon-γ and TLR4 Signaling. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 734966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou B, Lin W, Long Y, et al. Notch signaling pathway: architecture, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013, 45, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field JJ, Burdick MD, DeBaun MR, et al. The role of fibrocytes in sickle cell lung disease. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e33702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka A, Bashir K. Tumor Lysis Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518985/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Pritchard KA Jr, Besch TL, Wang J, et al. Differential Effects of Lovastatin and Allopurinol Therapy in a Murine Model of Sickle Cell Disease. Blood. 2005, 106, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar A, Kuo A, Frishman WH. Allopurinol as a cardiovascular drug. Cardiol Rev. 2011, 19, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood KC, Hebbel RP, Granger DN. Endothelial cell NADPH oxidase mediates the cerebral microvascular dysfunction in sickle cell transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul DK, Liu XD, Choong S, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM, Hebbel RP. Anti-inflammatory therapy ameliorates leukocyte adhesion and microvascular flow abnormalities in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004, 287, H293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti M, Al-Matrouk A, Channanath A, Hebbar P, Al-Mulla F, Thanaraj TA. Distribution of HLA-B Alleles and Haplotypes in Qatari: Recommendation for Establishing Pharmacogenomic Markers Screening for Drug Hypersensitivity. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 891838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean L, Kane M. Allopurinol Therapy and HLA-B*58:01 Genotype. In: Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M, Esquivel B, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ, eds. Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK127547/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Xolair (omalizumab) FDA Approval History. Drugs.com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/history/xolair.html (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Kaplan AP, Giménez-Arnau AM, Saini SS. Mechanisms of action that contribute to efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2017, 72, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin EJ, Dupuis J, Larson MG, et al. Genome-wide association with select biomarker traits in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8 (Suppl 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Suliman A, Elsarraf NA, Baqishi M, Homrany H, Bousbiah J, Farouk E. Patterns of mortality in adult sickle cell disease in the Al-Hasa region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2006, 26, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaj Zeen M, Mohamed NE, Mady AF, et al. Predictors of Mortality in Adults With Sickle Cell Disease Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit in King Saud Medical City, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023, 15, e38817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An P, Barron-Casella EA, Strunk RC, Hamilton RG, Casella JF, DeBaun MR. Elevation of IgE in children with sickle cell disease is associated with doctor diagnosis of asthma and increased morbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011, 127, 1440–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awojoodu AO, Keegan PM, Lane AR, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase is activated in sickle cell erythrocytes and contributes to inflammatory microparticle generation in SCD. Blood. 2014, 124, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees DC, Kilinc Y, Unal S, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of canakinumab in children and young adults with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2022, 139, 2642–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ruiz M, Aguado JM. Risk of infection associated with anti-TNF-α therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018, 16, 939–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contejean A, Janssen C, Orsini-Piocelle F, Zecchini C, Charlier C, Chouchana L. Increased risk of infection reporting with anti-BCMA bispecific monoclonal antibodies in multiple myeloma: A worldwide pharmacovigilance study. Am J Hematol. 2023, 98, E349–E353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, EM. Extinguishing the fire in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2022, 139, 2578–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovey A, Somani A, Belcher JD, et al. A monocyte-TNF-endothelial activation axis in sickle transgenic mice: Therapeutic benefit from TNF blockade. Am J Hematol. 2017, 92, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelowo O, Edunjobi AS. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis coexisting with sickle cell disease: two case reports. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr1020114889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simvastatin Prices, Coupons, Copay Cards & Patient Assistance - Drugs.com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/simvastatin (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Allopurinol Prices, Coupons, Copay Cards & Patient Assistance - Drugs.com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/allopurinol (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Ilaris Prices, Coupons, Copay Cards; Patient Assistance. Drugs.com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/ilaris (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Xolair Prices, Coupons, Copay Cards & Patient Assistance - Drugs.com. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/price-guide/xolair (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Bulger M, Bender MA, van Doorninck JH, et al. Comparative structural and functional analysis of the olfactory receptor genes flanking the human and mouse beta-globin gene clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97, 14560–14565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang Q, Kathiresan S, Lin JP, Tofler GH, O’Donnell CJ. Genome-wide association and linkage analyses of hemostatic factors and hematological phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8 (Suppl. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold EA, Penny LA, Nienhuis AW, Forget BG. An olfactory receptor gene is located in the extended human beta-globin gene cluster and is expressed in erythroid cells. Genomics. 1999, 61, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Zhao H, Fu N, Chen L. The diversified function and potential therapy of ectopic olfactory receptors in non-olfactory tissues. J Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 2104–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchil PD, Hinz A, Siegel S, et al. TRIM protein-mediated regulation of inflammatory and innate immune signaling and its association with antiretroviral activity. J Virol. 2013, 87, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian D, Cong Y, Wang R, Chen Q, Yan C, Gong D. Structural insight into the human SID1 transmembrane family member 2 reveals its lipid hydrolytic activity. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng MY, Wang L, Song YY, et al. Sidt2 is a key protein in the autophagy-lysosomal degradation pathway and is essential for the maintenance of kidney structure and filtration function. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estelius J, Lengqvist J, Ossipova E, et al. Mass spectrometry-based analysis of cerebrospinal fluid from arthritis patients—immune-related candidate proteins affected by TNF blocking treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SNP * | Gene * | Interacting drug | ATC code (s) | Interaction Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3135006 | HLA-DQB1 | Infliximab | L04AB02 | 0.23 |

| Aspirin | B01AC06/ N02BA01 | 0.10 | ||

| rs2395522 | HLA-DRB1 | Pitavastatin | C10AA08 | 0.48 |

| Azathioprine | L04AX01 | 0.06 | ||

| Pravastatin | C10AA03 | 0.09 | ||

| Atorvastatin | C10AA05 | 0.04 | ||

| Simvastatin | C10AA01 | 0.05 | ||

| Rosuvastatin | C10AA07 | 0.10 | ||

| Fluvastatin | C10AA04 | 0.20 | ||

| Tocilizumab | L04AC07 | 0.48 | ||

| Adalimumab | L04AB04 | 0.07 | ||

| Rilonacept | L04AC04 | 0.80 | ||

| Canakinumab | L04AC08 | 1.19 | ||

| Anakinra | L04AC03 | 0.27 | ||

| Etanercept | L04AB01 | 0.09 | ||

| Infliximab | L04AB02 | 0.23 | ||

| Glatiramer | L03AX13 | 0.51 | ||

| Aspirin | B01AC06/ N02BA01 | 0.03 | ||

| rs2844806 | HLA-A | Fenofibrate | C10AB05 | 0.15 |

| Peginterferon alfa-2a | L03AB11 | 0.13 | ||

| Peginterferon alfa-2b | L03AB10 | 0.12 | ||

| rs2524035 | HLA-G | Simvastatin | C10AA01 | 1.05 |

| rs2494250 | FCER1A | Omalizumab | R03DX05 | 0.94 |

| rs3132946 rs3132940 rs9267898 rs3096702 |

NOTCH4 | Allopurinol | M04AA01 | 0.58 |

| * Genetic variants and mapped genes associated with sickle cell disease severity identified in our genome wide association study involving Saudi patients [15]. | ||||

| SNP | Gene | Pocket Score | PDB Code | AlphaFold Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7933549 | OR51V1 | 0.83 | ---- | AF-Q9H2C8-F1 |

| rs112098990 | OR52A1 | 0.82 | ---- | AF-Q9UKL2-F1 |

| rs2472530 | OR52A5 | 0.82 | ---- | AF-Q9H2C5-F1 |

| rs147062602 rs10838058 rs10837853 rs78253695 rs180750244 |

OR51B5 | 0.86 | ---- | AF-Q9H339-F1 |

| rs12361955 | OR51S1 | 0.84 | ---- | AF-Q8NGJ8-F1 |

| rs3740999 rs11038294 rs12272467 |

TRIM6 | 0.8 | ---- | AF-Q9C030-F1 |

| rs67573252 | TRIM22 | 0.87 | ---- | AF-Q8IYM9-F1 |

| rs2342380 | TRIM34 | 0.82 | 2EGP | ---- |

| rs10535646 | SIDT2 | 0.84 | 7Y68 | ---- |

| rs3845624 | CADM3 | 0.7 | 1Z9M | ---- |

| MPTX1 | 0.81 | ---- | AF-A8MV57-F1 | |

| * Genetic variants and mapped genes associated with sickle cell disease severity identified in our genome wide association study involving Saudi patients [15]. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).