Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Target Proteins

2.2. Computational Modelling Studies

2.2.1. Computer Hardware Used for Computational Modelling Studies

2.2.2. Preparation of MAPK, PrKC1 and BFA for Docking and MD Simulation

2.2.3. Induced Fit Ligand Docking of BFA into PrKC1 and MAPK

2.2.4. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Studies

2.2.5. Post-Dynamic Analysis

2.2.6. MM/GBSA Free Binding Energy Calculation

2.2.7. Thermodynamic Binding Free Energy (BFE) Calculation

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Data Analyis of PrKC1 and MAPK

3. Results

3.1. Screening Glycosylation Targets

| BFA targets | Known actives (3D/2D) |

| CYP19A1 (Cytochrome P450 Family 19 Subfamily A Member 1) | 55/ 69 |

| ATP12A (ATPase H+/K+ Transporting Non-Gastric Alpha2 Subunit) | 03/ 10 |

| RPS6KA5 (Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase A5) | 04/ 03 |

| AR (Androgen Receptor) | 163 / 56 |

| *PRKCA (Protein Kinase C Alpha) | 49/ 203 |

| PDCD4 (Programmed Cell Death Protein 4) | 0/8 |

| PGR (Progesterone Receptor) | 31/ 40 |

| TAS2R31 (Taste Receptor Type 2 Member 31) | 0/1 |

| PSEN2 (Presenilin 2) | 66/ 0 |

| PPARG- (Perioxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma) | 12/10 |

| JAK1 (Janus Kinase 1) | 112/ 0 |

| CDC25A (Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2) | 8/ 15 |

| PDE10A (Phosphodiesterase 10A) | 201/ 0 |

| MAPK14 (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 14) | 118/ 0 |

| *MAP2K1 (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1) | 133/ 0 |

3.2. Structural Evaluation of Ligand-Induced Protein Conformational Alteration

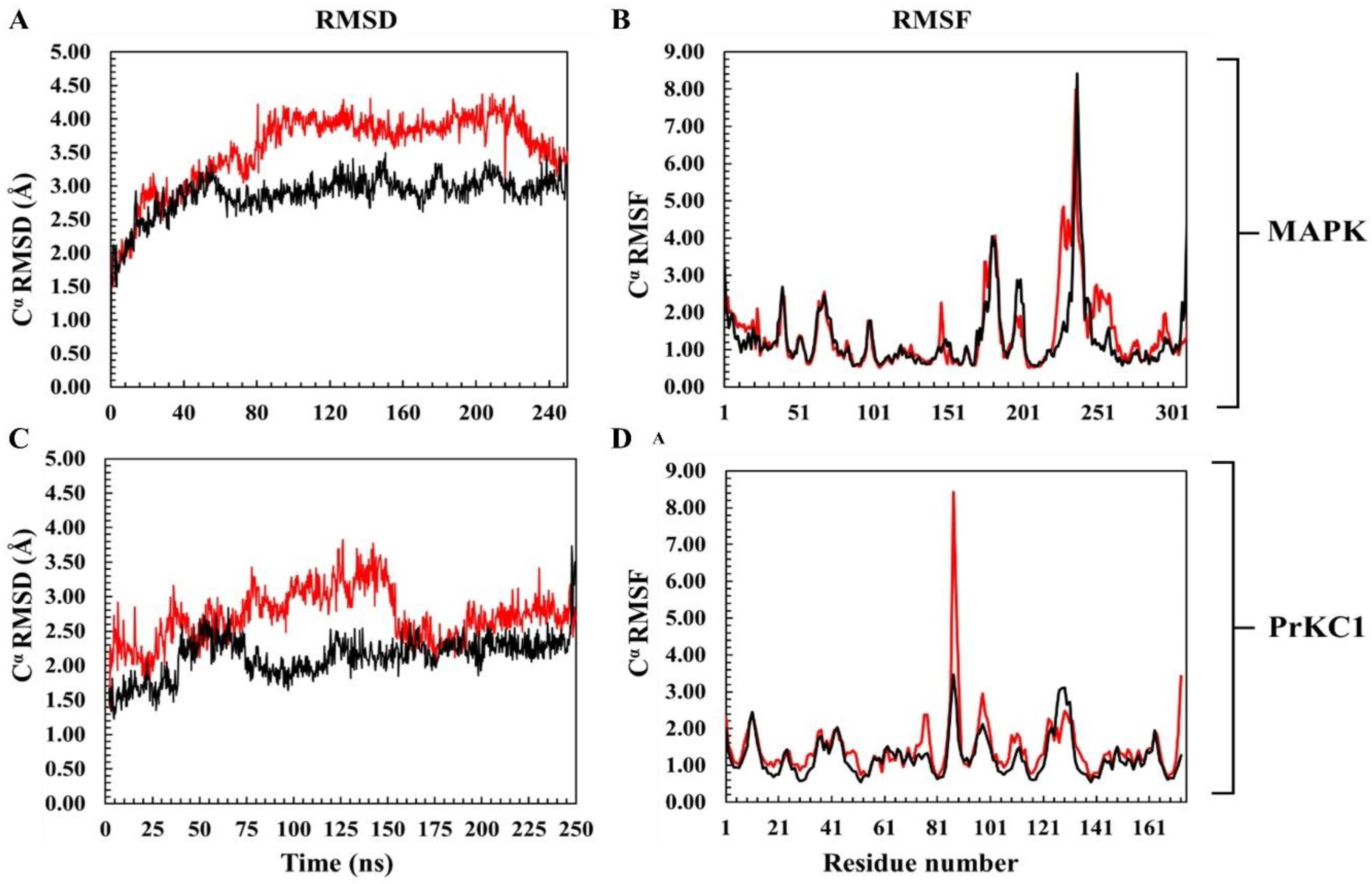

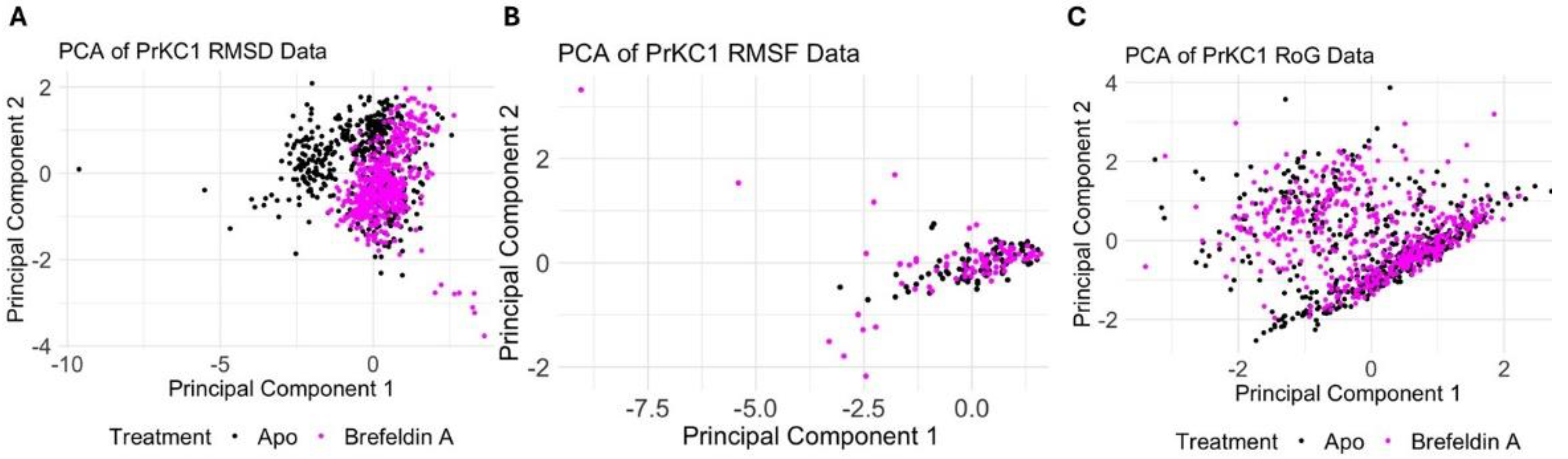

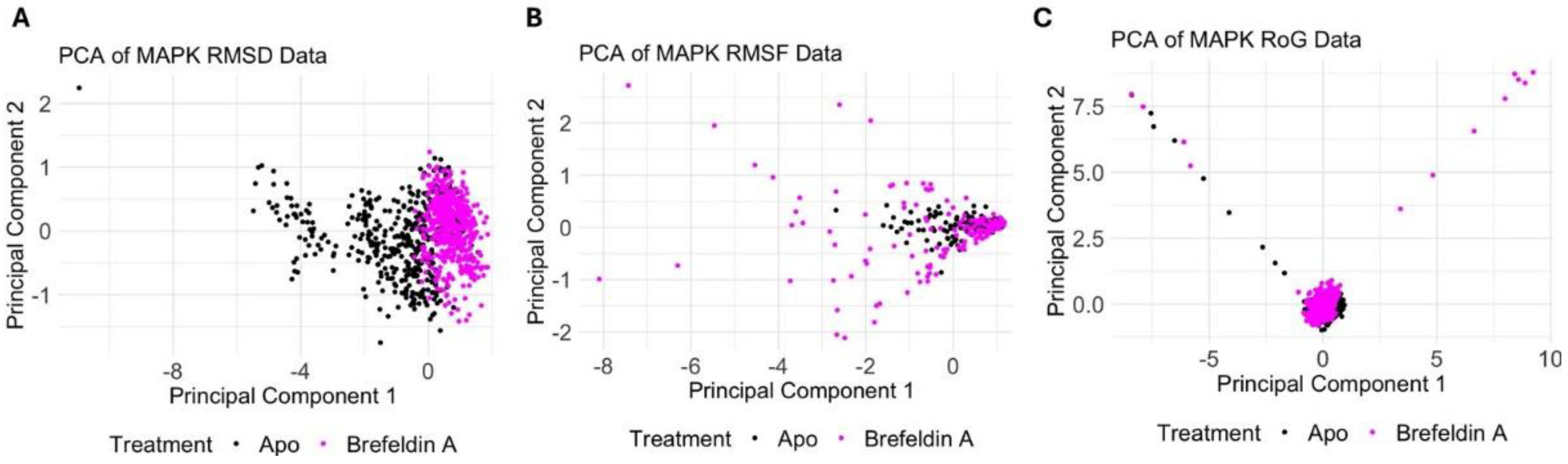

- The RMSF plots of the bound MAPK and PrKC1 show trajectory patterns quite similar to the apo (Figure 1B and 1D). As their fluctuation pattern is quite close to that of their corresponding apo, differences relative to the apo thus can’t be made. The estimated mean RMSF of MAPK is 1.44±1.02Å, while that of the apo is 1.33±0.99Å. In the case of PrKC1, the mean RMSF is 1.47±0.80Å for the BFA-bound PrKC1, while the apo form is 1.24±0.55Å.

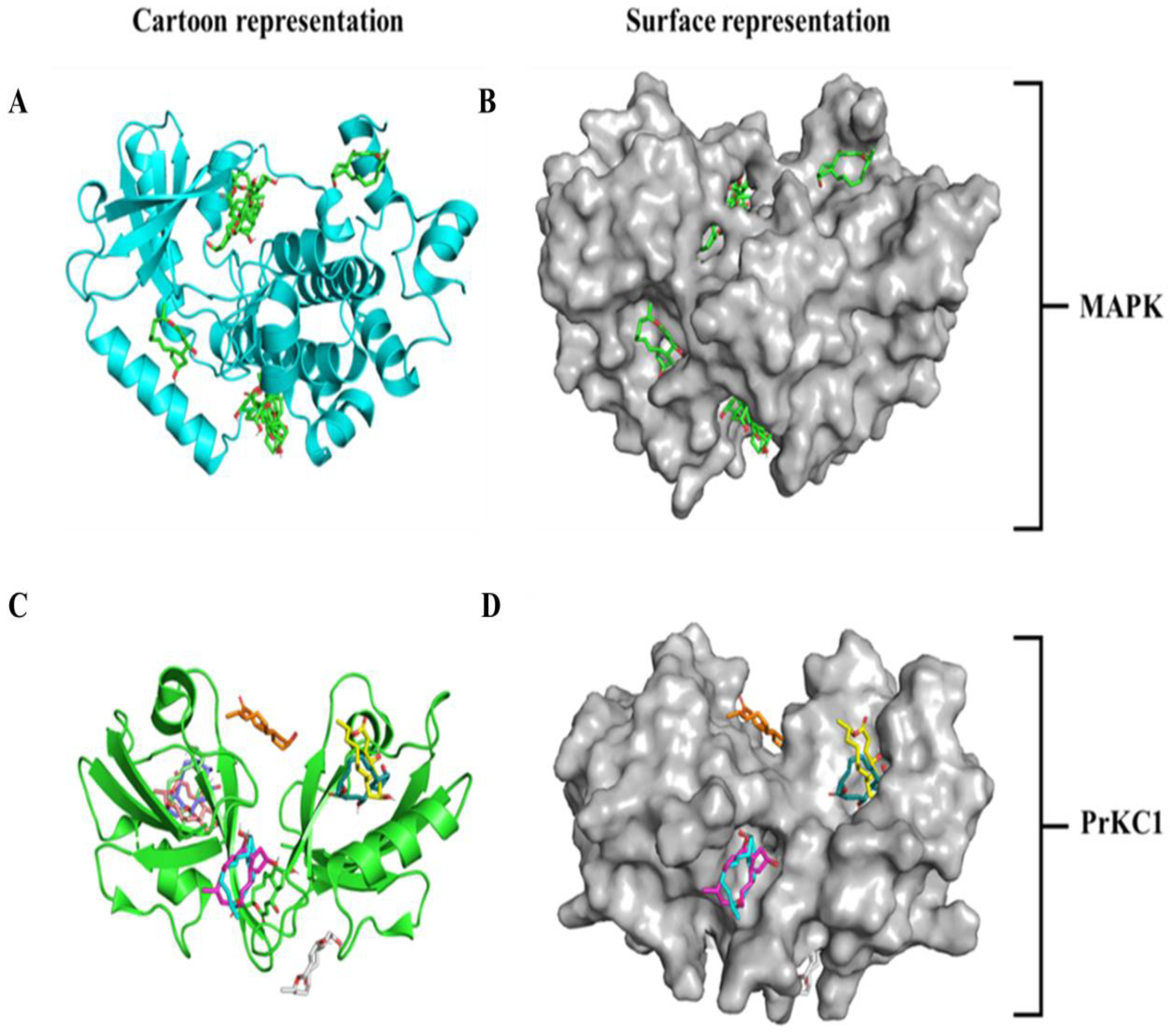

3.3. Molecular Docking and Binding Site Visualization of BFA with MAPK and PrKC1

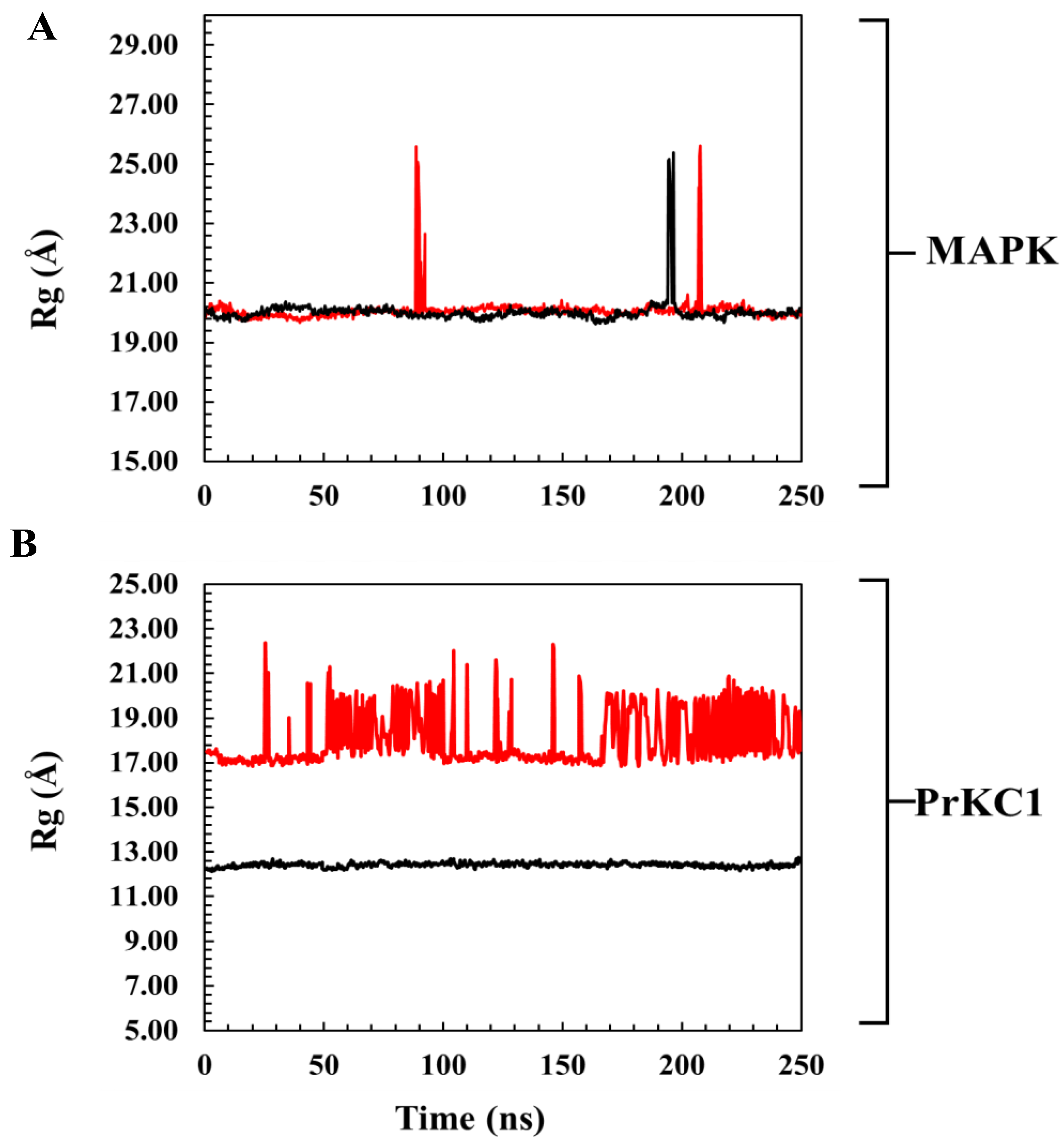

3.4. Time-Based BFA-Induced Structural Mobility

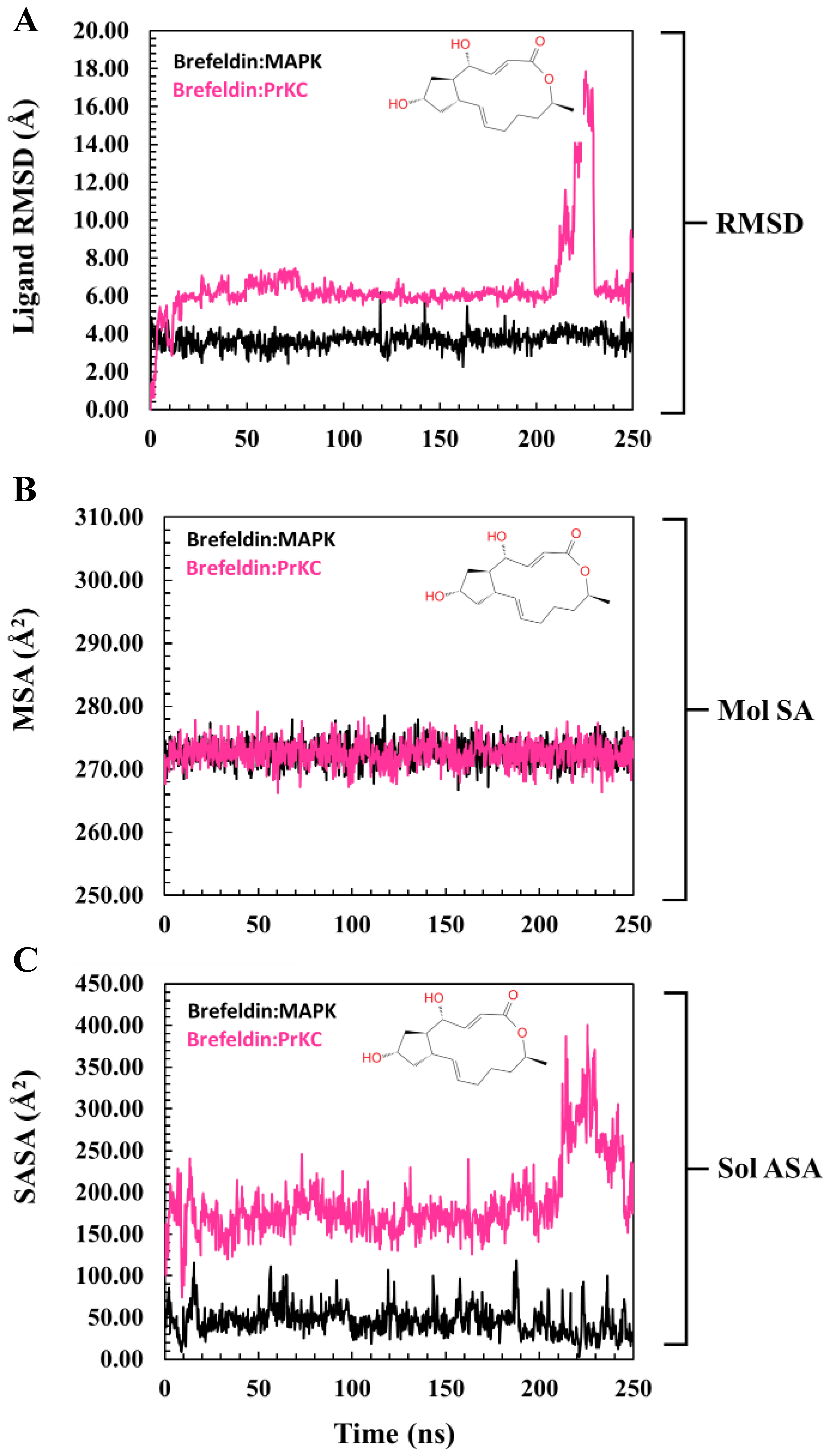

3.5. Structural Investigation of BFA Dynamics Across the MD Simulation Timeline

3.5. Medium-Based Visualisation of BFA Interaction with Binding Site Residues

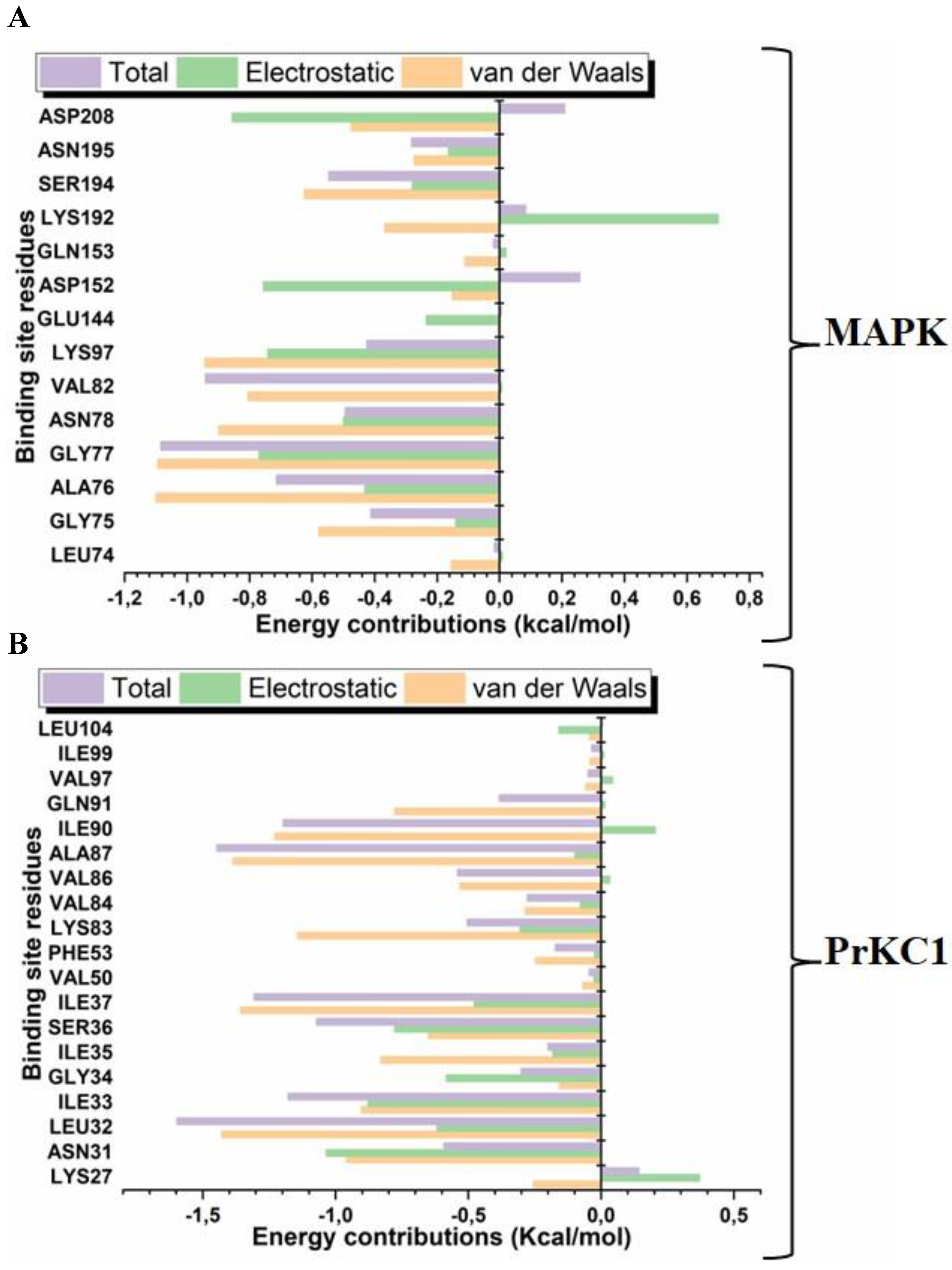

3.6. Evaluation of Structural Properties Contributing to Binding Interactions

3.7. Quantification Thermodynamic Evaluation of Binding Affinity

| Compounds | Energy components (kcal/mol) | ||||

| ∆Evdw | ∆Eele | ∆Ggas | ∆Gsol | ∆Gbind | |

| MAPK _ BFA | -28.23±3.24 | -11.91±7.52 | -40.14±9.14 | 17.97±5.65 | -22.18±4.50 |

| PrKC1_BFA | -27.44±3.89 | -6.31±8.66 | -33.75±10.19 | 9.81±5.82 | -23.9±5.36 |

3.8. Molecular Dynamics Data Analyis of PrKC1 and MAPK

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reily, C.; Stewart, T.J.; Renfrow, M.B.; Novak, J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nature reviews. Nephrology 2019, 15, 346-366. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.F.; Campos, D.; Reis, C.A.; Gomes, C.J.T.i.C. Targeting glycosylation: a new road for cancer drug discovery. 2020, 6, 757-766.

- Varki, A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3-49.

- Pinho, S.S.; Reis, C.A. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nature reviews. Cancer 2015, 15, 540-555. [CrossRef]

- Stowell, S.R.; Ju, T.; Cummings, R.D. Protein glycosylation in cancer. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2015, 10, 473-510.

- Mereiter, S.; Balmaña, M.; Campos, D.; Gomes, J.; Reis, C.A. Glycosylation in the Era of Cancer-Targeted Therapy: Where Are We Heading? Cancer cell 2019, 36, 6-16. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liang, M.; Wang, B.; Kang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, S. GALNT12 is associated with the malignancy of glioma and promotes glioblastoma multiforme in vitro by activating Akt signaling. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2022, 610, 99-106. [CrossRef]

- Arey, B. The role of glycosylation in receptor signaling. Glycosylation 2012, 26, 50262.

- Li, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, M.; Klein, J.D.; Sands, J.M.; Chen, G. Activation of protein kinase C-α and Src kinase increases urea transporter A1 α-2, 6 sialylation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 2015, 26, 926-934. [CrossRef]

- Lien, E.C.; Nagiec, M.J.; Dohlman, H.G. Proper protein glycosylation promotes mitogen-activated protein kinase signal fidelity. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 115-124. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Fan, D. Tunicamycin specifically aggravates ER stress and overcomes chemoresistance in multidrug-resistant gastric cancer cells by inhibiting N-glycosylation. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 2018, 37, 272. [CrossRef]

- Mackay, H.J.; Twelves, C.J. Protein kinase C: a target for anticancer drugs? Endocrine-related cancer 2003, 10, 389-396. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H. Protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes and cancer. New Journal of Science 2014, 2014.

- Lien, C.F.; Chen, S.J.; Tsai, M.C.; Lin, C.S. Potential Role of Protein Kinase C in the Pathophysiology of Diabetes-Associated Atherosclerosis. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 716332. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.S.; Newton, A.C. Phosphorylation at conserved carboxyl-terminal hydrophobic motif regulates the catalytic and regulatory domains of protein kinase C. The Journal of biological chemistry 1997, 272, 18382-18390. [CrossRef]

- Keranen, L.M.; Newton, A.C. Ca2+ differentially regulates conventional protein kinase Cs' membrane interaction and activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 25959-25967.

- Keranen, L.M.; Newton, A.C. Ca2+ differentially regulates conventional protein kinase Cs' membrane interaction and activation. The Journal of biological chemistry 1997, 272, 25959-25967. [CrossRef]

- Mosior, M.; Newton, A.C. Mechanism of the apparent cooperativity in the interaction of protein kinase C with phosphatidylserine. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 17271-17279. [CrossRef]

- Suriya, U.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Integration of In Silico Strategies for Drug Repositioning towards P38α Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) at the Allosteric Site. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, Z.; Kazanaviciute, V.; Shubchynskyy, V.; Kvederaviciute, K.; Schwanninger, M.; Rozhon, W.; Stumpe, M.; Mauch, F.; Bartels, S.; Ulm, R.; et al. Dual control of MAPK activities by AP2C1 and MKP1 MAPK phosphatases regulates defence responses in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany 2022, 73, 2369-2384. [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, A.; Manfroni, G.; Cecchetti, V.; Barreca, M.L. A Comprehensive Structural Overview of p38α Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase in Complex with ATP-Site and Non-ATP-Site Binders. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Ardito, F.; Giuliani, M.; Perrone, D.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review). International journal of molecular medicine 2017, 40, 271-280. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.Y. Regulatory Mechanisms and Novel Therapeutic Targeting Strategies for Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases. Chemical reviews 2018, 118, 1069-1091. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, K.; Liu, P.; Sha, N.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; Zhuo, L.; Liu, G.; et al. GFAT1-linked TAB1 glutamylation sustains p38 MAPK activation and promotes lung cancer cell survival under glucose starvation. Cell discovery 2022, 8, 77. [CrossRef]

- Esteva, F.J.; Sahin, A.A.; Smith, T.L.; Yang, Y.; Pusztai, L.; Nahta, R.; Buchholz, T.A.; Buzdar, A.U.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Bacus, S.S. Prognostic significance of phosphorylated P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and HER-2 expression in lymph node-positive breast carcinoma. Cancer 2004, 100, 499-506. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.K.; Basu, S.; Hu, J.; Yie, T.A.; Tchou-Wong, K.M.; Rom, W.N.; Lee, T.C. Selective p38 activation in human non-small cell lung cancer. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2002, 26, 558-564. [CrossRef]

- Junttila, M.R.; Ala-Aho, R.; Jokilehto, T.; Peltonen, J.; Kallajoki, M.; Grenman, R.; Jaakkola, P.; Westermarck, J.; Kähäri, V.M. p38alpha and p38delta mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms regulate invasion and growth of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5267-5279. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, D.M.; Büll, C.; Madsen, T.D.; Lira-Navarrete, E.; Clausen, T.M.; Clark, A.E.; Garretson, A.F.; Karlsson, R.; Pijnenborg, J.F.A.; Yin, X.; et al. Identification of global inhibitors of cellular glycosylation. Nature communications 2023, 14, 948. [CrossRef]

- Bosshart, H.; Straehl, P.; Berger, B.; Berger, E.G. Brefeldin A induces endoplasmic reticulum-associated O-glycosylation of galactosyltransferase. Journal of cellular physiology 1991, 147, 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Chantalat, L.; Leroy, D.; Filhol, O.; Nueda, A.; Benitez, M.J.; Chambaz, E.M.; Cochet, C.; Dideberg, O. Crystal structure of the human protein kinase CK2 regulatory subunit reveals its zinc finger-mediated dimerization. The EMBO journal 1999, 18, 2930-2940. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, C.; Duncan, G.; Tufaro, F. New perspectives on the molecular basis of hereditary bone tumours. Molecular medicine today 1999, 5, 481-486. [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Swenson, L.L.; Fitzgibbon, M.J.; Hayakawa, K.; Ter Haar, E.; Behrens, A.E.; Fulghum, J.R.; Lippke, J.A. Structure of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein (MAPKAP) kinase 2 suggests a bifunctional switch that couples kinase activation with nuclear export. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 37401-37405. [CrossRef]

- Birringer, M.S.; Claus, M.T.; Folkers, G.; Kloer, D.P.; Schulz, G.E.; Scapozza, L. Structure of a type II thymidine kinase with bound dTTP. FEBS letters 2005, 579, 1376-1382. [CrossRef]

- Fischmann, T.O.; Smith, C.K.; Mayhood, T.W.; Myers, J.E.; Reichert, P.; Mannarino, A.; Carr, D.; Zhu, H.; Wong, J.; Yang, R.S.; et al. Crystal structures of MEK1 binary and ternary complexes with nucleotides and inhibitors. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 2661-2674. [CrossRef]

- Grest, G.S.; Kremer, K. Molecular dynamics simulation for polymers in the presence of a heat bath. Physical review. A, General physics 1986, 33, 3628-3631. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, E. OriginPro 9.1: scientific data analysis and graphing software-software review. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2014, 54, 1552-1552.

- R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2013.

- Tang, Y.; Horikoshi, M.; Li, W.J.R.J. ggfortify: unified interface to visualize statistical results of popular R packages. 2016, 8, 474.

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, W357-w364. [CrossRef]

- Aloke, C.; Iwuchukwu, E.A.; Achilonu, I. Exploiting Copaifera salikounda compounds as treatment against diabetes: An insight into their potential targets from a computational perspective. Computational biology and chemistry 2023, 104, 107851. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, I.A.; Olotu, F.A.; Agoni, C.; Soliman, M.E.S. Deciphering the 'Elixir of Life': Dynamic Perspectives into the Allosteric Modulation of Mitochondrial ATP Synthase by J147, a Novel Drug in the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Chemistry & biodiversity 2019, 16, e1900085. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, I.A.; Olotu, F.A.; Agoni, C.; Soliman, M.E.S. In Silico Repurposing of J147 for Neonatal Encephalopathy Treatment: Exploring Molecular Mechanisms of Mutant Mitochondrial ATP Synthase. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 2020, 21, 1551-1566. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.P.; Hong, Y.H.; Yang, P.M. In silico and in vitro identification of inhibitory activities of sorafenib on histone deacetylases in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86168-86180. [CrossRef]

- Ruegenberg, S.; Mayr, F.; Atanassov, I.; Baumann, U.; Denzel, M.S. Protein kinase A controls the hexosamine pathway by tuning the feedback inhibition of GFAT-1. Nature communications 2021, 12, 2176. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Nadeem, A.; Rydström, A.; Puthia, M.; Svanborg, C. Targeting of nucleotide-binding proteins by HAMLET--a conserved tumor cell death mechanism. Oncogene 2016, 35, 897-907. [CrossRef]

- Karshikoff, A.; Nilsson, L.; Ladenstein, R. Rigidity versus flexibility: the dilemma of understanding protein thermal stability. The FEBS journal 2015, 282, 3899-3917. [CrossRef]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Yuan, L.C.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Klausner, R.D. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 1989, 56, 801-813. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.G.; Finazzi, D.; Klausner, R.D. Brefeldin A inhibits Golgi membrane-catalysed exchange of guanine nucleotide onto ARF protein. Nature 1992, 360, 350-352. [CrossRef]

| Term description | Matching potential target proteins in the network |

| Pathways in cancer | PPARG,MAP2K1,AR,PRKCA,RPS6KA5,JAK1 |

| Proteoglycans in cancer | MAPK14,PDCD4,MAP2K1,PRKCA |

| PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer | MAPK14,MAP2K1,JAK1 |

| MAPK signalling pathway | MAPK14,MAP2K1,PRKCA,RPS6KA5 |

| PI3K-Akt signalling pathway | MAP2K1,PRKCA,JAK1 |

| AGE-RAGE signalling pathway in diabetic complications | MAPK14,PRKCA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).