1. Introduction

The proliferation of digital infrastructure, open data initiatives, and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies has fundamentally reshaped the design and operation of Smart Cities. These systems promise increased transparency, data-driven decision-making, and improved public services. However, this digital transformation also introduces a growing spectrum of cybersecurity threats. The security of open data platforms is critical: public sector systems process and expose datasets that may directly affect public safety, infrastructure management, or critical citizen services. Therefore, the design of secure-by-default architectures and risk-informed governance mechanisms is essential.

A significant challenge lies in the absence of tailored cybersecurity frameworks that consider both the interdependencies of Smart City processes, and the criticality of the data involved. Traditional information security standards such as ISO/IEC 27001 and NIST SP 800-53B [

1] offer generic baselines but often lack operational granularity when applied to context-rich urban environments. Moreover, common vulnerability assessment practices fail to account for business continuity parameters like Recovery Time Objective (RTO), Maximum Tolerable Period of Disruption (MTPD), or Maximum Tolerable Data Loss (MTDL), which are vital for prioritizing mitigations in urban ecosystems.

In this context, Business Impact Analysis (BIA) provides a powerful but underutilized methodology for connecting cybersecurity decisions with real-world consequences. BIA is widely adopted in disaster recovery and business continuity planning, but its use in modeling cyber threats in Smart City environments is still emerging. Previous works have explored process-driven security modeling using Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) [

2], including security-focused extensions such as SecBPMN [

3] or domain-specific models such as BPMN-SC [

4]. However, these approaches rarely incorporate BIA metrics to quantify impact and prioritize controls based on measurable continuity criteria.

This study proposes an integrated methodology that extends BPMN-SC with embedded BIA metrics, applied to the real-world case of the Hradec Kralove Region Open Data Platform. Our goal is to build a cybersecurity baseline model that not only maps the functional flows of public service data but also supports automated derivation of mitigation measures based on service criticality. We introduce:

A formalized model for capturing data availability, confidentiality, and integrity requirements within BPMN diagrams.

A BIA-based annotation mechanism for process steps, assigning RTO, MTPD, and MTDL parameters to assess operational impact.

An algorithmic approach to match risks with security controls, optimizing for coverage and efficiency.

A practical evaluation of risk severity and mitigation through the automated publishing process of Smart City datasets.

The research builds upon national strategies and legislative frameworks, including the EU NIS2 Directive [

5], ENISA’s baseline for IoT security [

6], and recommendations from cybersecurity ontologies such as UCO [

7] and CASE [

8]. In contrast to previous static taxonomies, our approach emphasizes dynamic prioritization, allowing municipalities to align cyber defense with the operational relevance of data assets. The methodology contributes to the field by bridging process modeling, continuity management, and adaptive risk mitigation in the cybersecurity governance of Smart Cities.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Chapter 2 reviews relevant literature in Smart City cybersecurity, with emphasis on security frameworks (e.g., ISO/IEC 27001, NIST SP 800-53B), process modeling (BPMN, BPMN-SC), and the limited but growing role of Business Impact Analysis (BIA). This forms the conceptual basis of the paper. Chapter 3 introduces the methodology that combines BPMN-SC with BIA metrics such as RTO, MTPD, and MTDL, allowing for risk-informed modeling of public service processes.

Chapter 4 presents an algorithm that prioritizes mitigation measures based on risk coverage efficiency. The approach aligns with the objectives of the ARTISEC project focused on AI-based cybersecurity planning. Chapter 5 applies the model to the Hradec Kralove Open Data Platform. The evaluation validates the ability of the approach to identify critical data flows and optimize protective measures. Chapter 6 summarizes key findings and discusses strategic and regulatory implications, including future potential for automation and AI-supported compliance under frameworks like NIS2. Key contributions of the paper include:

A novel integration of Business Impact Analysis (BIA) with Smart City process modeling, allowing impact-oriented cybersecurity assessment through quantifiable metrics such as RTO, MTPD, and MTDL.

A formal methodology for embedding BIA parameters directly into BPMN-SC diagrams, enabling process-aware prioritization of security controls based on service criticality and data classification.

The development of a decision-support algorithm that selects mitigation measures based on risk coverage efficiency, optimizing the allocation of cybersecurity resources while fulfilling continuity requirements.

A validation of the proposed framework in a real-world case study of the Hradec Kralove Region Open Data Platform, demonstrating its applicability in municipal public administration.

Alignment of the proposed model with current and emerging regulatory standards, including ISO/IEC 27001, ISO 22301, and the EU NIS2 Directive, facilitating its adoption in compliance-driven environments.

A contribution to the ARTISEC project by linking static process models with AI-ready structures for future automation in threat impact recalibration and risk-based security planning.

The proposed approach offers a replicable, regulation-aligned, and impact-driven framework which also provides a replicable foundation for municipal cybersecurity planning, supporting both the strategic vision and operational resilience of Open Data in Smart Cities.

3. Business Impact Analysis Methodology

This chapter outlines a methodology that integrates Business Impact Analysis (BIA) with BPMN-SC to assess cybersecurity risks and service continuity parameters within Smart City systems [

25]. The goal is to enable data-driven prioritization of security measures by embedding quantitative indicators into process models [

26,

27].

3.1. Establishing Impact Criteria

The first step is to define a set of impact criteria that reflect the severity of disruptions from the perspective of financial costs, reputational damage, and personal safety risks. These criteria are aligned with recommendations under the EU NIS2 Directive and reflect national best practices for critical infrastructure protection [

28,

29]. Impact levels are categorized to guide both risk assessment and the selection of proportionate safeguards

Table 2.

3.2. Availability as a Key Parameter

The first evaluation criterion is availability. Availability is defined as ensuring that information is accessible to authorized users at the moment it is needed. In some cases, the destruction of certain data may be viewed as a disruption of availability. It is therefore essential to clarify what vendors mean when they state that their system guarantees, for example, 99.999% availability. If the base time period is defined as 365 days per year, this figure allows for a maximum unavailability of about 5 minutes annually [

30,

31].

At first glance, five-nines availability seems sufficient. However, it is important to define what exactly is meant by “system.” Vendors often refer only to the hardware layer, omitting operating systems and applications. These layers are frequently excluded from SLAs and come with no guaranteed availability, even though in practice, they are often the cause of outages

Table 3.

Even though annual percentage availability is widely used, it is far more precise and practical to define:

If RTO = 0, this implies fully redundant infrastructure. RTO defines how quickly operations must resume, and is central to disaster recovery planning. RPO defines the volume of data loss an organization is willing to accept. Together, RTO and RPO form the foundation of continuity planning.

Additional availability-related parameters include:

MIPD (Maximum Initial Programmed Delay): the maximum allowed time to initialize and start a process after a failure.

MTPD (Maximum Tolerable Period of Disruption): the maximum downtime allowed before the disruption causes unacceptable consequences for operations.

MTDL (Maximum Tolerable Data Loss): the maximum data loss acceptable before critical impact occurs.

When high availability is required, duplication of all system components (power, disks, servers, etc.) is a logical solution. However, duplicating multi-layer architectures increases system complexity and the risk of failure (e.g., zero-day vulnerabilities or failover misconfigurations).

If each component guarantees 99.999% availability, the availability of the entire system, when modeled as three interdependent layers, is approximately 99.997%, which equates to about 16 minutes of allowable downtime per year. Such configurations must also handle failover, active/passive role switching, and user redirection without compromising data integrity. Otherwise, “split-brain” scenarios may occur, where independent operation of redundant components leads to data divergence and inconsistency.

To support BIA, impact evaluations must assess downtime in intervals of 15 minutes, 1 hour, 1 day, and 1 week. The following availability categories apply:

C: Low importance—downtime of up to 1 week is acceptable.

B: Medium importance—downtime should not exceed one business day.

A: High importance—downtime of several hours is tolerable but must be resolved promptly.

A+: Critical—any unavailability causes serious harm and must be prevented.

These assessments help derive:

MIPD: Based on severity across time intervals using logic functions (e.g., if 15min = B/A/A+, then MIPD = 15min).

MTPD: Longest acceptable time without recovery.

MTDL: Largest data volume/time tolerable for loss.

Example of MIPD determination:

If unavailability at 15min = B/A/A+ → MIPD = 15 min.

Else if 1hr = B/A/A+ → MIPD = 1 h.

Else if 1 day = B/A/A+ → MIPD = 1 day.

Else if 1 week = B/A/A+ → MIPD = 1 week.

Else → MIPD = “BE” (beyond acceptable threshold).

These values ensure the architecture design meets operational expectations for continuity and resilience. Rather than relying solely on annual percentage availability, this methodology emphasizes two well-defined parameters:

Both RTO and RPO are critical inputs to continuity planning and are directly linked to the architectural design of backup, redundancy, and failover mechanisms.

3.3. Confidentiality and Integrity Considerations

Another essential parameter evaluated in this methodology is confidentiality. Confidentiality is commonly defined as ensuring that information is only accessible to those who are authorized to view it. In cybersecurity, unauthorized access or disclosure of data is considered a breach of confidentiality. To address this, organizations should implement appropriate classification schemes and technical, organizational, and physical security measures [

32].

The commonly used classification scheme includes:

Public: Information intended for general public access.

Internal: Information accessible only to internal employees.

Confidential: Information restricted to selected employees.

Strictly Confidential: Highly sensitive information accessible only to designated personnel.

The classification level may change during the information lifecycle. To maintain confidentiality, proper controls should be in place for data access, encryption, and logging.

Integrity ensures the correctness and completeness of information. Any unauthorized or accidental modification—whether due to error, attack, or system failure—can violate data integrity. The risk is especially high if such modifications remain undetected for long periods.

To ensure data integrity, the following techniques can be applied:

Cryptographic Hash Functions (e.g., SHA-256): Used to verify whether data has changed.

Digital Signatures: Validate the authenticity and integrity of documents using asymmetric cryptography.

Checksums: Simple integrity-check algorithms.

Message Authentication Codes (MAC): Combine a secret key with data to generate verifiable integrity tags.

Digital Certificates: Verify sender authenticity and data integrity via trusted certificate authorities.

A best practice includes logging all data changes and implementing layered encryption—e.g., encrypting data at the application level before storage, and using checksum validation upon retrieval. While this shifts risk from the database to the application, it enables protection even against insider threats when managed through HSM (Hardware Security Module) devices.

3.4. Example of Security Baseline Application

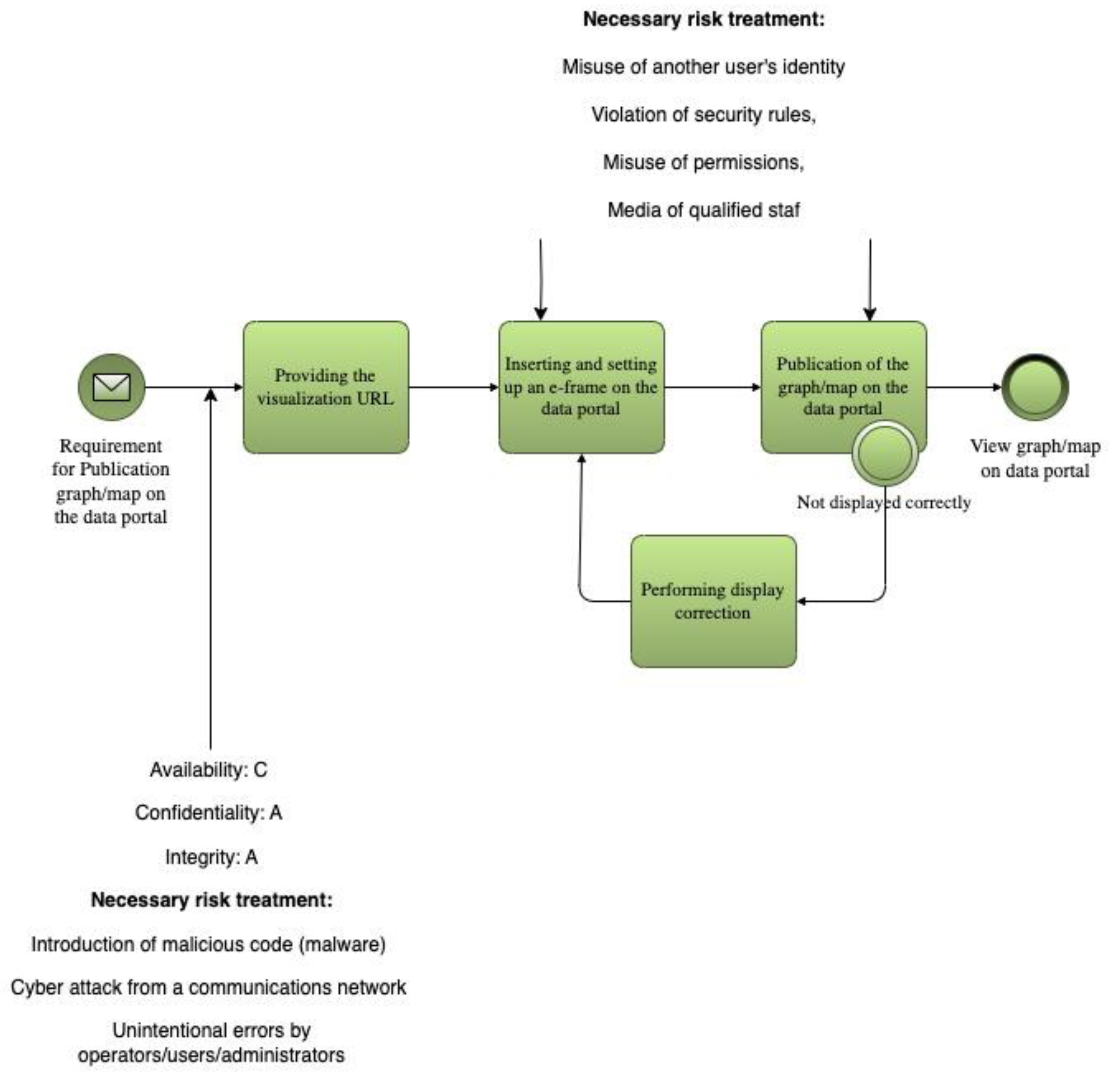

The implementation of the security baseline for open data in the Hradec Kralove Region, including the automated selection of security measures, is demonstrated in the process of data publication and visualization through the regional open data portal.

The process starts with a request to publish a chart or map visualization. The request, containing a visualization URL, is received from a user or administrator. The system then processes the request and provides the appropriate URL. The visualization is embedded into an e-frame on the portal and properly configured.

Following this, the visualization is published. A display check is performed to verify correct rendering. If the visualization fails to display, a corrective action loop is triggered (“Display Fix Loop”), after which the publishing attempt is repeated.

Once the visualization passes the check, it is made available to the public. End users can then view the newly published charts and maps through the open data portal interface.

This example demonstrates how BIA metrics and process modeling can be used not only for threat analysis but also for enhancing the resilience of real-world Smart City services. To operationalize BIA in Smart City contexts, this study embeds RTO/RPO/MTDL thresholds directly into BPMN-SC diagrams. Each process task or data flow is annotated with impact parameters. This enables simulation of cascading failures and evaluation of interdependencies among services (e.g., how a disruption in environmental data publishing affects public health dashboards).

Additionally, the model includes:

Maximum Tolerable Period of Disruption (MTPD): Time beyond which continued disruption is unacceptable.

Maximum Tolerable Data Loss (MTDL): Volume or timeframe of acceptable data loss based on legal and operational factors.

This step establishes a machine-readable baseline for impact, which can be further linked to automated risk assessment and mitigation tools as outlined in the next chapter.

The result is a context-sensitive, standardized input layer for cybersecurity planning that reflects actual service delivery constraints, not just abstract technical vulnerabilities

Table 4.

The risk posture of the system is significantly influenced by the level of integrity and confidentiality assigned to data prior to publication. These two dimensions are critical to ensuring the relevance and trustworthiness of the open data portal’s Operations

Table 5.

Key cybersecurity risks that must be addressed, based on this risk analysis, include:

Identity theft

Security breaches or misuse of credentials/media

Cyber-attacks via communication networks

Operator or administrator errors

Lack of qualified personnel

These risks primarily affect the staff involved in the creation, publication, and visualization of data sets, including both system administrators and data processors. The recommended mitigation measures reflect the need for:

Identity and access management

Malware detection and prevention

Continuous staff training and awareness

4. Automated Selection of Risk-Mitigation Measures from Security Baseline

4.1. The Greeddy Alghorithm for Automated Selection of Risk-Mitigation

The task is to select the best measure (rows of the table) to address the given risks (columns of the table). We have a table of measures with rows M and columns representing defined risks R. Each row of M mitigates only some of the risks R. Given a set of measures SM, the task is to select from SM the rows that cover the maximum number of defined risks R, considering the effectiveness of each measure E.

Definitions:

Set of measures (rows), where M is the total number of measures —

Set of risks (columns), where R is the total number of risks —

A subset of measures from which we are selecting -

— a binary value indicating whether measure covers risk (if it does, ; otherwise ).

— efficiency of measure , where 1 is the least efficient and 5 is the most efficient.

— decision variable, where indicates that measure is selected, and indicates that it is not selected.

Objective function — maximizing risk coverage with respect to efficiency:

This formula states that each risk is assigned a value of 1 if it is mitigated by at least one measure, with measures with a higher having a higher weight.

Constraints — ensuring that measures are selected only from the SM set:

This constraint says that the selection of measures is limited to the set (a subset of all measures).

Risk coverage - ensuring that the risk is covered:

This constraint ensures that each risk is covered by at least one selected measure.

Goal of the Algorithm:

The goal is to find a subset of measures that maximizes coverage of risks R, considering their efficiency.

Mathematical Procedure:

-

Initialization:

- ○

Define the set of uncovered risks .

- 2.

-

Scoring Each Measure:

- ○

For each measure , compute its score:

“

a higher priority if more risks are covered).

Iterative Measure Selection:

Repeat the following steps until all risks are covered or no more measures can be selected:

risks are covered, the algorithm terminates.

Output:

The set of selected measures S, which maximizes the number of covered risks considering the efficiency.

Therefore, if the objective is to maximize overall risk coverage, taking into account the effectiveness of each selected measure, we can assume that these constraints are met:

Each measure can only cover some of the risks represented by the matrix.

-

The selection of measures must maximize the coverage of all risks R, with preference given to measures with a higher efficiency score .

Formulate the mathematics problem as follows:

determines whether a measure addresses a risk .

is the decision variable for selecting the measure.

weights the selection based on the efficiency of the measure, with higher efficiency receiving a lower penalty.

The goal is to select measures that cover the maximum number of risks with the highest possible efficiency.

Example:

Consider 3 measures and 5 risks. The coverage matrix and efficiency are defined as follows:

-

Compute the score for each measure:

- ○

: 3 risks covered, efficiency 5 → score

- ○

: 3 risks covered, efficiency 3 → score

- ○

: 3 risks covered, efficiency 4 → score

Select , since it has the highest score (1.0).

Update the set of uncovered risks. covers risks .

Recompute scores for remaining measures and (adjust for the updated set of uncovered risks).

Continue iterating until all risks are covered or no further improvement is possible.

4.2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Using the Greedy Algorithm

The following sub-chapter discusses the Advantages and disadvantages of using the Greedy algorithm for a model with 40 measures and 14 risks. The measures were focused mainly on speed, simplicity, efficiency and other important factors.

Advantages:

-

Speed: The Greedy algorithm is fast because it makes locally optimal choices at each step. With 40 measures and 14 risks, the algorithm should perform efficiently.

- ○

The time complexity is roughly , where mmm is the number of measures and nnn is the number of risks. For and , this is computationally manageable.

Simplicity: The algorithm is easy to implement and does not require complex setups or specialized optimization libraries. It can be realized in any programming language.

Approximation: Greedy algorithms often provide solutions that are close to optimal, especially when there are no significant overlaps in risk coverage between the measures.

Consideration of Efficiency: The algorithm accounts for the efficiency of measures, which is beneficial when measures have significantly different efficiencies.

Disadvantages:

-

Local Optimality: The Greedy algorithm focuses on making the best choice at each step, which can lead to suboptimal solutions. If measures have large overlaps in risk coverage, the Greedy algorithm might select solutions that are not globally optimal.

- ○

It may choose a measure that covers many risks in the short term, but in later steps, more efficient measures might be ignored.

Inability to Consider Dependencies: If there are dependencies between measures or if certain measures have different priorities, the Greedy algorithm cannot effectively account for them. This may result in a less effective overall solution.

Sensitivity to Efficiency Distribution: If the efficiencies of the measures are too closely distributed, the Greedy algorithm might fail to find a sufficiently optimal solution. Small differences in efficiency may cause the algorithm to overlook measures that would be more beneficial in the long run.

A suitable proof of the efficiency and correctness of the above relations and methods can be made by formal argumentation. A structured approach to proving the correctness of the generalized formula and method is presented here:

Theoretical Proof (Formal Reasoning)

Objective Function:

We aim to maximize risk coverage while considering the efficiency of each measure. The objective function is:

The formula above correctly balances two elements:

Risk Coverage: Each represents whether a measure addresses a risk . Summing over all jjj allows us to count how many risks are covered by measure .

Efficiency Weighting: Each term is divided by , which penalizes measures with lower efficiency. Higher efficiency (lower ) contributes more favorably to the objective function.

Therefore, the objective function maximizes the total number of risks covered, weighted by the efficiency of the measures. Selecting a measure with higher efficiency () will lead to a lower penalty , promoting efficient measures.

Selection Criteria

The decision variable ensures that we only select a measure if it is part of the solution. The sum of over all jjj correctly counts the number of risks covered by the selected measures. The theoretical model thereby correctly represents the goal of covering the maximum number of risks with the highest possible efficiency.

Greedy Algorithm Proof

The Greedy algorithm described in earlier sections makes locally optimal choices at each step by selecting the measure with the best coverage-to-efficiency ratio.

Step 1: Greedy Choice Property

Greedy algorithms work when the greedy choice property holds, i.e., making a local optimal choice at each step leads to a globally optimal solution.

In this case, each step selects the measure that maximizes:

This ratio ensures that at each step, the algorithm picks the measure that offers the greatest coverage of uncovered risks per unit of efficiency. Although Greedy algorithms do not always guarantee a globally optimal solution for all types of optimization problems, for risk coverage problems with efficiency weighting, this method often produces solutions that are close to optimal.

Step 2: Greedy Algorithm Approximation Bound

For problems like weighted set cover, where we aim to cover a set of elements (in this case, risks) with a minimal weighted set of subsets (in this case, measures with efficiency weighting), it is known that a Greedy algorithm provides an approximation within a logarithmic factor of the optimal solution. The Greedy algorithm provides a logarithmic approximation bound for set cover problems:

Where is the harmonic number, and nnn is the number of elements to be covered (in this case, the number of risks).

Therefore, while the Greedy algorithm may not always provide the exact optimal solution, it is guaranteed to be within a factor of of the optimal solution, making it a good heuristic for problems like this.

5. Discussion and Results

A theoretical proof is accompanied by empirical validation, where we test the algorithm on a real or simulated dataset to demonstrate that the relationships and methods function correctly in practice.

Example Simulation:

We can simulate a problem with 40 measures and 14 risks. Each measure has a random efficiency score between 1 and 5, and the coverage matrix is randomly generated. We run the Greedy algorithm and compare it to a brute-force optimal solution or known benchmarks for validation.

Simulation Steps:

- 4.

Generate a random coverage matrix , where each element is 0 or 1.

- 5.

Assign efficiency values randomly to each measure from the set .

- 6.

Run the Greedy algorithm to select measures that maximize coverage while considering efficiency.

- 7.

Compare results with brute-force selection (optimal solution for small instances) or other optimization algorithms (like integer linear programming).

Expected Outcome:

The Greedy algorithm should select measures that cover most risks while minimizing the efficiency penalty.

For small instances (e.g., 10 measures and 5 risks), we can compute the optimal solution via brute force and compare it to the Greedy result. The Greedy solution should be close to optimal.

For larger instances (e.g., 40 measures and 14 risks), Greedy will efficiently find a near-optimal solution in a fraction of the time it would take to compute the exact solution.

Conclusion from Empirical Testing:

The empirical testing demonstrates that the proposed Greedy algorithm and formula function correctly, providing solutions that cover a high number of risks efficiently. The approximation quality will be close to the theoretical guarantees.

Empirically verify

To empirically verify the use of the genetic algorithm (GA) for selecting optimal risk coverage measures and its comparison with the Greedy algorithm, a Python test was designed and implemented. This test involved generating random data for 14 risks and 40 measures, implementing both algorithms and evaluating their performance. The following metrics were validated and used for comparison.

Coverage: number of risks covered.

Effectiveness: sum of the effectiveness scores of the selected measures.

Number of measures selected: Total number of measures selected.

Execution time: The time required to run each algorithm.

import numpy as np

import random

import time

from functools import reduce

# Seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

# Number of risks and measures

num_measures = 40

num_risks = 14

# Generate random coverage matrix (40x14) and effectiveness vector (1-5)

coverage_matrix = np.random.choice([0, 1], size=(num_measures, num_risks), p=[0.7, 0.3])

effectiveness = np.random.randint(1, 6, size=num_measures)

# Helper function to calculate fitness

def fitness(individual):

covered_risks = reduce(np.logical_or, [coverage_matrix[i] for i in range(num_measures) if individual[i] == 1], np.zeros(num_risks))

covered_risks_count = np.sum(covered_risks)

total_efficiency = sum([effectiveness[i] for i in range(num_measures) if individual[i] == 1])

return covered_risks_count, total_efficiency

# Genetic Algorithm (GA)

def genetic_algorithm(population_size=100, generations=200, mutation_rate=0.1):

# Initialize random population

population = [np.random.choice([0, 1], size=num_measures) for _ in range(population_size)]

best_individual = None

best_fitness = (0, 0)

for generation in range(generations):

# Evaluate fitness of each individual

fitness_scores = [fitness(individual) for individual in population]

# Select the best individual

for i, f in enumerate(fitness_scores):

if f > best_fitness:

best_fitness = f

best_individual = population[i]

# Selection (roulette wheel selection based on fitness)

total_fitness = sum(f [0] for f in fitness_scores)

selected_population = []

for _ in range(population_size):

pick = random.uniform(0, total_fitness)

current = 0

for i, f in enumerate(fitness_scores):

current += f [0]

if current > pick:

selected_population.append(population[i])

break

# Crossover (single-point crossover)

new_population = []

for i in range(0, population_size, 2):

parent1, parent2 = selected_population[i], selected_population[i+1]

crossover_point = random.randint(0, num_measures-1)

child1 = np.concatenate((parent1[:crossover_point], parent2[crossover_point:]))

child2 = np.concatenate((parent2[:crossover_point], parent1[crossover_point:]))

new_population.extend([child1, child2])

# Mutation

for individual in new_population:

if random.random() < mutation_rate:

mutation_point = random.randint(0, num_measures-1)

individual[mutation_point] = 1 - individual[mutation_point] # Flip bit

population = new_population

return best_individual, best_fitness

# Greedy Algorithm

def greedy_algorithm():

selected_measures = []

remaining_risks = np.zeros(num_risks)

while np.sum(remaining_risks) < num_risks:

best_measure = None

best_coverage = -1

best_efficiency = -1

for i in range(num_measures):

if i in selected_measures:

continue

measure_coverage = np.sum(np.logical_and(coverage_matrix[i], np.logical_not(remaining_risks)))

if measure_coverage > best_coverage or (measure_coverage == best_coverage and effectiveness[i] > best_efficiency):

best_measure = i

best_coverage = measure_coverage

best_efficiency = effectiveness[i]

if best_measure is None:

break

selected_measures.append(best_measure)

remaining_risks = np.logical_or(remaining_risks, coverage_matrix[best_measure])

total_efficiency = sum(effectiveness[i] for i in selected_measures)

return selected_measures, len(selected_measures), total_efficiency

# Run tests and compare

# Genetic Algorithm

start_time = time.time()

best_solution_ga, best_fitness_ga = genetic_algorithm()

time_ga = time.time() - start_time

# Greedy Algorithm

start_time = time.time()

selected_measures_greedy, num_selected_greedy, efficiency_greedy = greedy_algorithm()

time_greedy = time.time() - start_time

# Results

print(“Genetic Algorithm:”)

print(f”Best solution (GA) covers {best_fitness_ga [0} risks with total efficiency {best_fitness_ga [

1]}”)

print(f”Time taken: {time_ga:.4f} seconds”)

print(“\nGreedy Algorithm:”)

print(f”Selected measures (Greedy) covers {num_risks} risks with total efficiency {efficiency_greedy}”)

print(f”Number of selected measures: {num_selected_greedy}”)

print(f”Time taken: {time_greedy:.4f} seconds”)

Implementation of genetic algorithm:

Initialize a random population of solutions. Fitness is calculated based on how many risks are covered and what the overall efficiency is. Selection is done by roulette wheel, crossover is single point and mutation shuffles random bits. The best solution is returned after a fixed number of generations. Genetic algorithm: It is expected to produce a near-optimal solution with a balance between risk coverage and efficiency measures, but may take longer.

An implementation of the Greedy algorithm:

Measures are selected based on how many uncovered risks they mitigate and their effectiveness. This process continues until all risks are covered or until no new measures can improve the solution. Greedy algorithm: It is expected to be faster, but may not find the best solution due to its greedy nature (locally optimal, but not globally optimal),

Table 6.

The empirical validation of the proposed methodology demonstrates its effectiveness for risk-based control selection in the context of Smart City cybersecurity. Simulated experiments using 40 candidate mitigation measures and 14 predefined risk scenarios allowed for performance benchmarking of two algorithmic strategies: a Greedy algorithm and a Genetic Algorithm (GA).

The Greedy approach, optimized for speed and simplicity, consistently produced near-optimal results with minimal computation time, making it well-suited for operational deployments and real-time decision-making. Conversely, the Genetic Algorithm exhibited slightly higher overall risk coverage and better balancing of control effectiveness, but required significantly more computational resources. Therefore, it appears more applicable for strategic scenario planning and simulation environments.

Key evaluation metrics, such as risk coverage, aggregate effectiveness, number of measures selected, and execution time, confirm the theoretical expectations. The Greedy algorithm, while locally optimal, aligns with logarithmic approximation bounds known for weighted set-cover problems. The GA-based method, albeit more computationally intensive, delivers a marginal improvement in solution quality and robustness.

Importantly, the integration of Business Impact Analysis (BIA) into process modeling via BPMN-SC enables impact-aware prioritization. This ensures alignment with continuity thresholds (RTO, MTPD, MTDL) and provides a clear rationale for selecting specific security measures based on their business-criticality. Unlike static baseline approaches (e.g., ISO/IEC 27001 Annex A or NIST SP 800-53B), this model dynamically maps protections to service-level needs and operational constraints.

The findings further support the utility of the ARTISEC project’s direction, namely the future use of AI-driven recalibration of BIA metrics based on telemetry data and evolving threat landscapes. This demonstrates that algorithmic selection of controls can be grounded not only in risk coverage efficiency, but also in measurable continuity and availability targets.