Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Rapidly growing tumours tend to exhibit a distribution of Ki67 levels in 2N DNA cells that skews toward the levels typically observed in mitotic cells. In contrast, slow-growing tumours show a distribution of Ki67 levels in 2N DNA cells that aligns more closely with the background Ki67 levels found in nearby non-cancerous tissue, while tumours with intermediate growth rates fall somewhere in between.

- With further validation, classifying tumours into these more specific categories could enhance prognosis and guide treatment choices for patients, while also offering insight into how tumours respond to ongoing therapies.

2. Mathematical Formulation

- i.

- Therapy received and,

- ii.

- Biological characteristics of the tumour/disease entity which are theoretically perceived to influence survival irrespective of and with respect to therapy given.

- 1)

- Optimum survival period So;

- 2)

- Tumour Stage [TS] (for all cancers, higher tumour stage numbers indicate more extensive disease. Stage IV cancers demonstrate distant spread to tissues and organs as well);

- 3)

- Number of cycles of chemotherapy administered [NCC]; and

- 4)

- Tumour proliferative index [K-i67].

- The Main Ideas

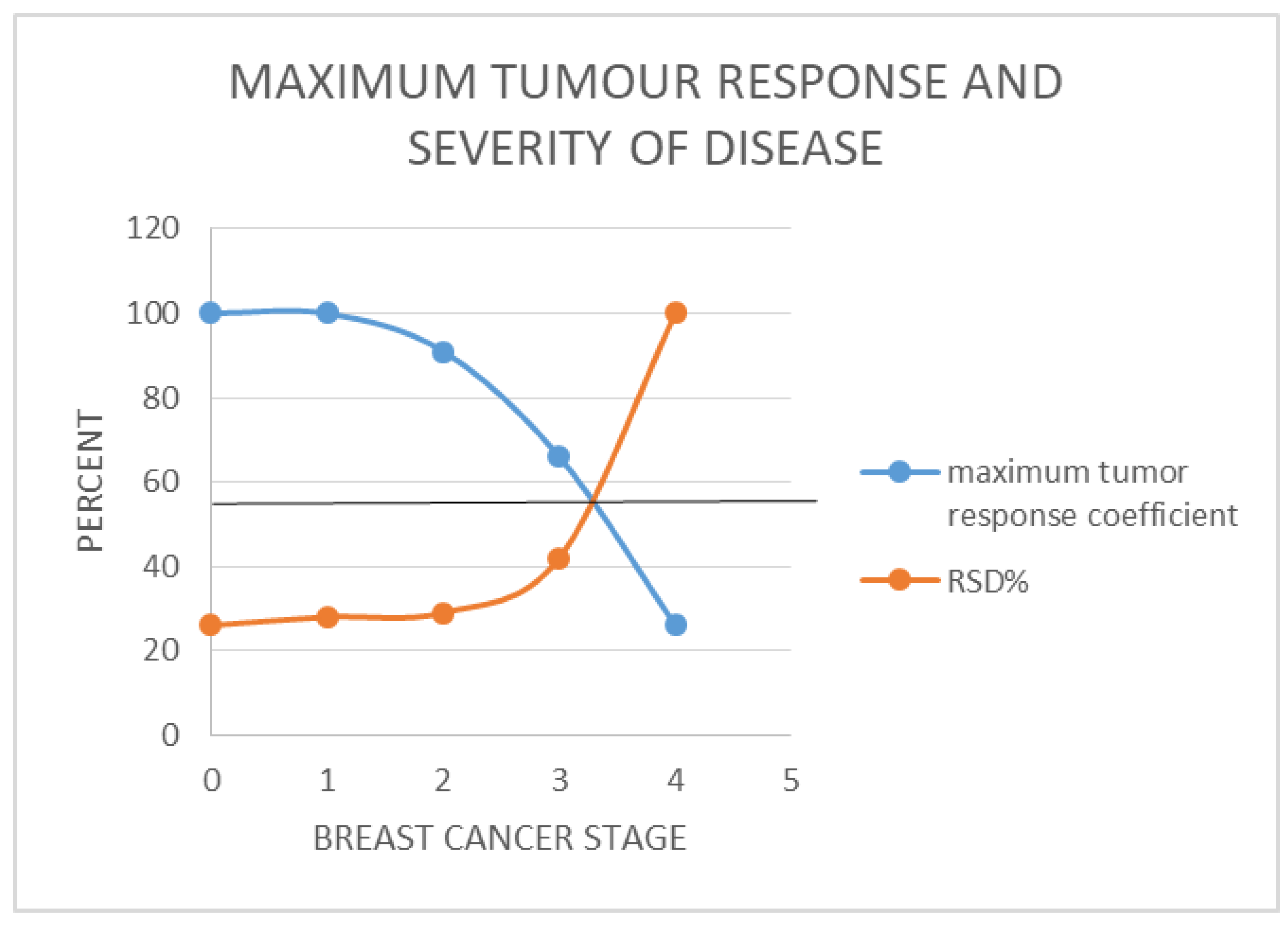

- The stage of disease at presentation

- Severity of the disease relative to stage I

- Reduced response to therapy due to higher tumour cell burden at presentation

- More severe disease at presentation lowers the survival rate after therapy.

- Stage IV breast cancer is 3.8 times as severe as stage I

- Stage III is 1.6 times as severe as stage I

- Stage II is 1.1 times as severe as stage I

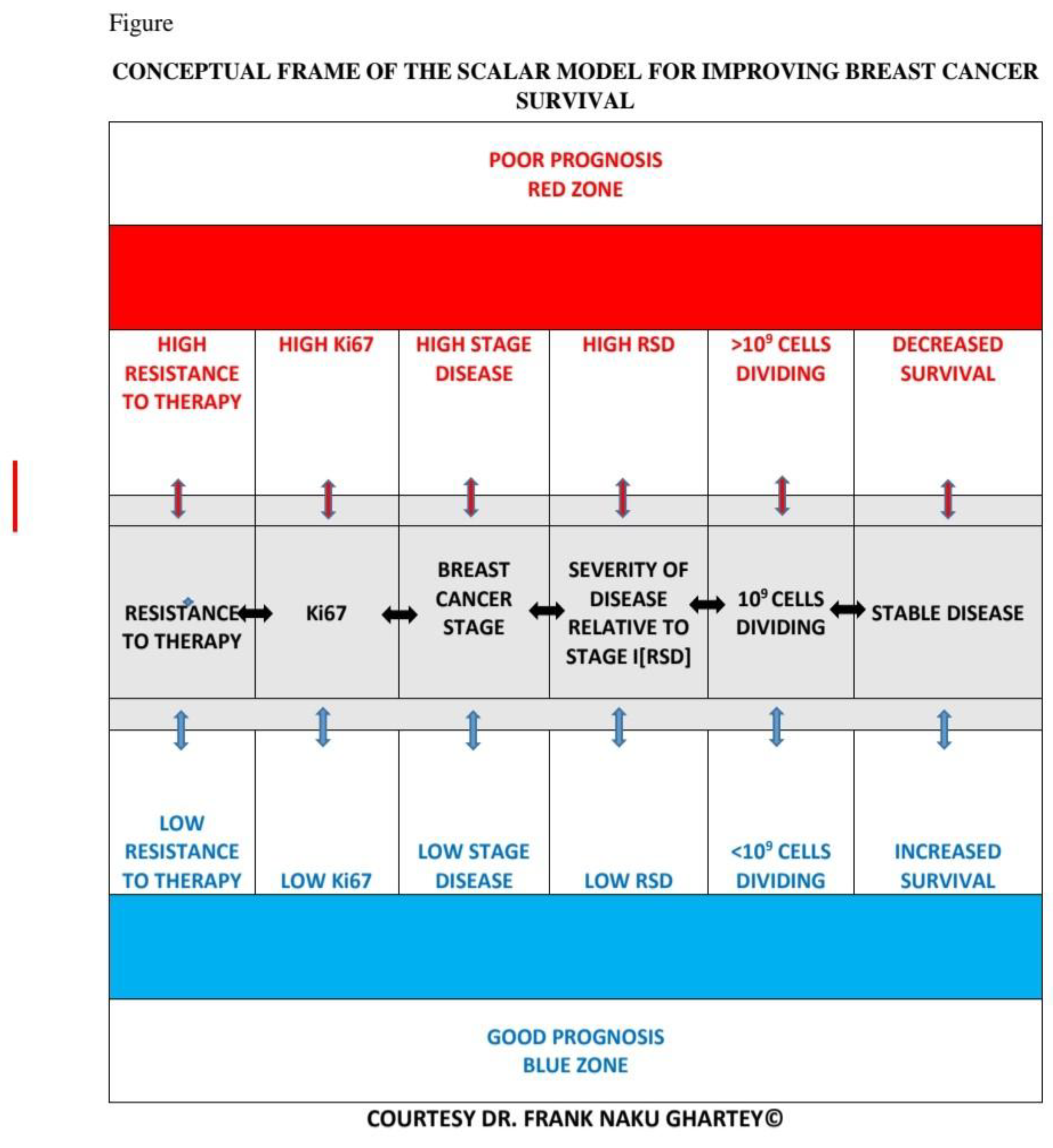

- Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

Determination of KC

- Reflects Treatment Response: Ki67 levels fluctuate with treatment, indicating therapy effectiveness and tumour aggressiveness.

- Captures Several Molecular Pathway Influence: Since growth factor signaling (e.g., HER2 activation) influences proliferation, Ki67 acts as a proxy for upstream dysregulation. It also helps this model to capture TNBCs as well which do not express some of these major upstream signaling receptors.

- Correlates with Prognosis: High Ki67 levels often indicate poorer survival, making it a robust survival predictor.

- Mathematically Feasible: Ki67 provides continuous, measurable data, allowing for precise modeling of treatment effects and patient outcomes.

- Grouping of Cases

- -

- Luminal A (ER+/PR+/HER2−)—Least aggressive, favorable prognosis.

- -

- Luminal B (ER+/PR+/HER2+)—More proliferative, intermediate prognosis.

- -

- Luminal AB (Mixed features of A and B).

- -

- TNBC (ER−/PR−/HER2−)—Most aggressive, poorest prognosis.

- -

- Metastatic Burden (CTC count and progression risk)

- -

- Immune Marker Status (PD-L1 positivity for immunotherapy suitability)

- -

- More cycles generally improve survival in early-stage cases if the need is clinically justified.

- -

- For advanced cases, increasing [NCC] may not significantly extend survival due to therapy resistance.

- -

- Low [TS] → Better response to treatment, leading to longer survival.

- -

- High [TS] → Lower response, reducing net survival gain per cycle.

- -

- Lower Ki67 (≤20%) → less aggressive tumour growth, improving therapy benefits.

- -

- Higher Ki67 (≥30%) → more aggressive tumour growth, reducing therapy benefits.

- -

- Higher coefficient → Significant survival impact from chemotherapy.

- -

- Lower coefficient → Minimal survival impact from chemotherapy.

- -

- Early-stage patients: Standard chemotherapy cycles (4–6) yield significant survival benefits.

- -

- Advanced-stage patients: Optimizing combination therapies (targeted therapy + immunotherapy) could increase survival where chemotherapy alone falls short as is done.

- -

- Personalized treatment: Using AI-driven reinforcement learning to adjust chemotherapy cycles based on real-time patient response.

- Predictive modelling based on these variables.

- -

- Continuously evaluate per patient group.

- -

- Adjust treatment intensity based on survival feedback from previous cycles.

- -

- Suggest alternative therapies for high-risk patients (low Tumour-Dependent Therapeutic Response Coefficient-TmdRxResCoef).

- -

- Bayesian Networks: Predict response variation using tumour progression.

- -

- Adaptive Learning Models: Dynamically refine chemotherapy cycles based on real-time patient response.

- -

- Federated Learning Frameworks: Multi-hospital collaboration optimizes treatment strategies globally.

- -

- Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (evaluating overall survival trends).

- -

- ROC curve performance analysis (assessing AI predictive power).

- -

- Treatment refinement (adjustments suggested based on TmdRxResCoef for personalized oncology).

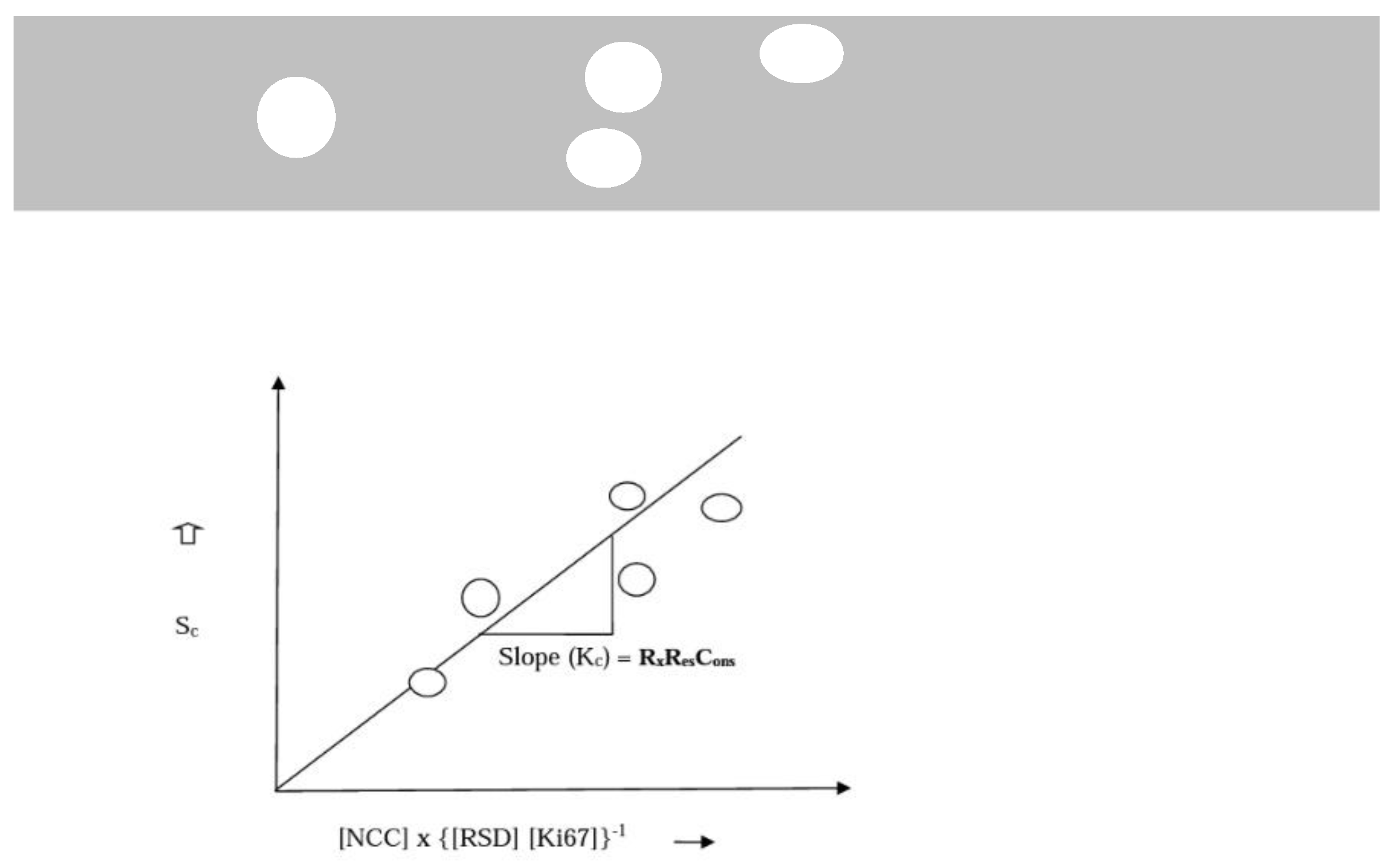

- Sc = Survival dependent on tumour characteristics and standardize treatment dose.

- Kc = Constant representing baseline survival per cycle/dose of treatment. Dependent on the stage of disease and tumour proliferation index.

- [NCC] = Number of Cycles of Chemotherapy (Treatment dose).

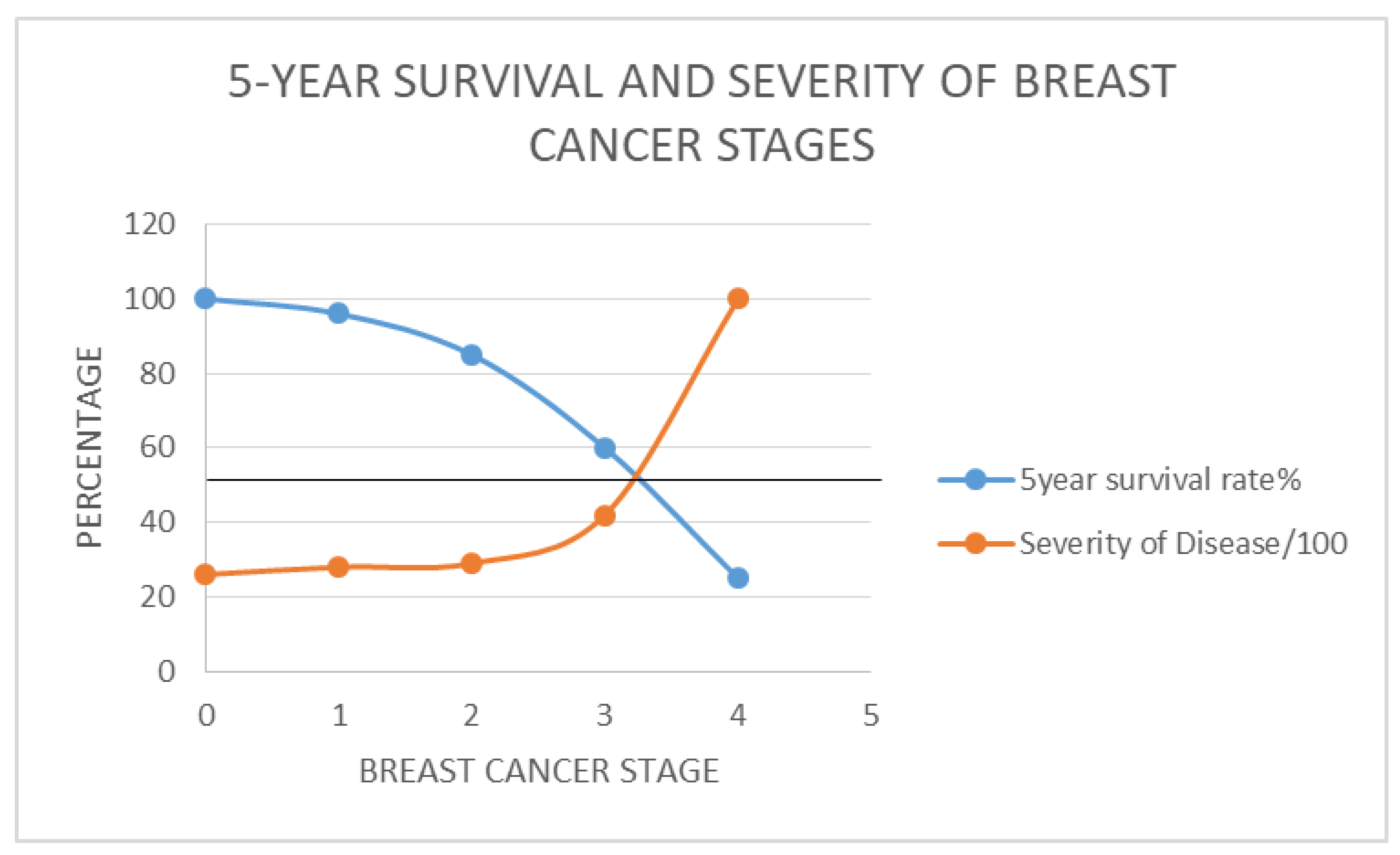

- [TS] = Tumour stage (reflecting disease progression and severity) ⇔ [RSD]-the relative severity of disease, calculated by comparing survival of each stage with stage I.

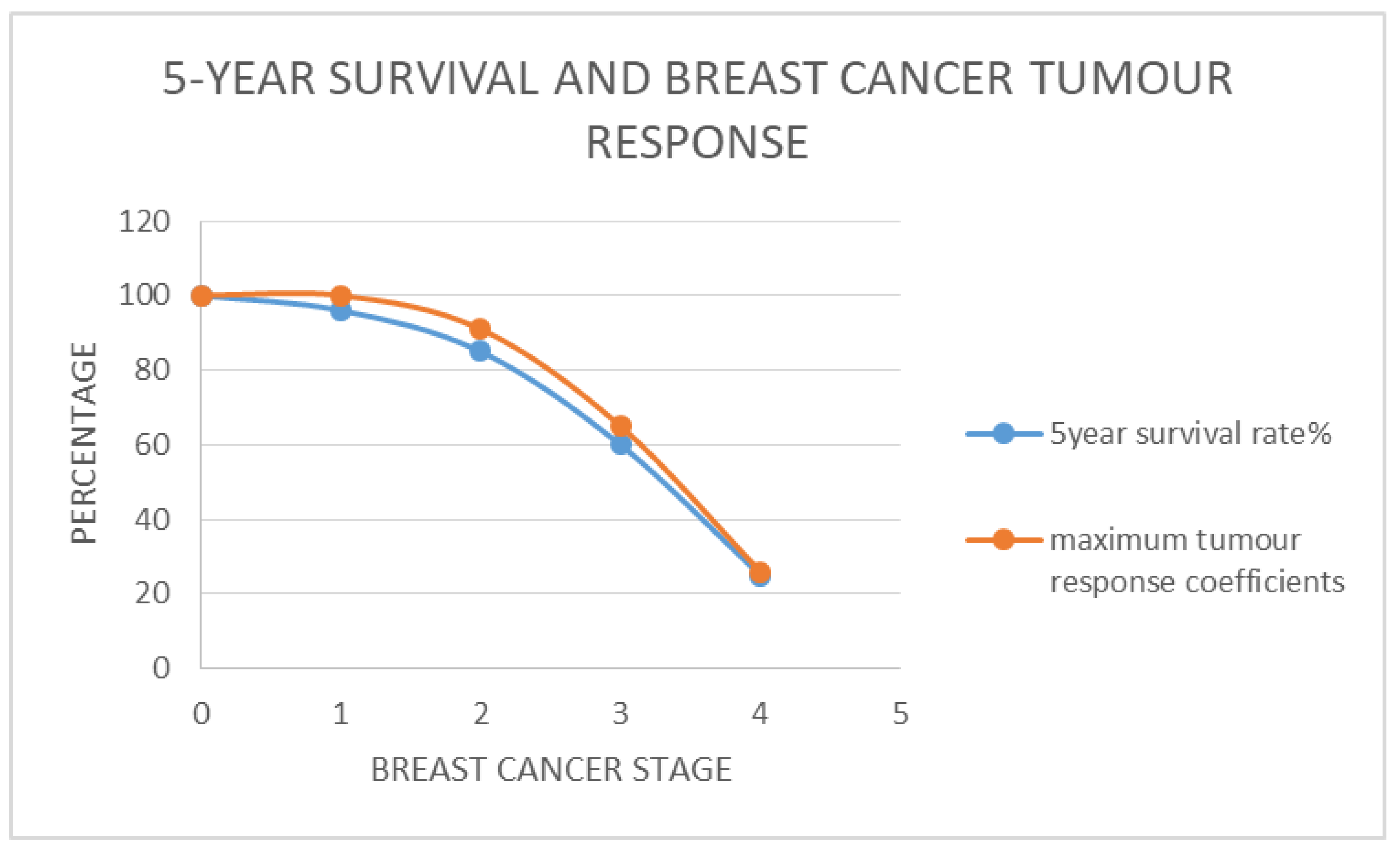

- [RSD] is preferred. It is a more nuanced reflection of the real-world relationships between the different stages of breast cancer (Figure 1 (b)).

- [Ki67] = Proliferation marker.

- -

- Higher [TS] and [Ki67] values → lower chemotherapy effectiveness, shorter survival.

- -

- Lower [TS] and [Ki67] values → better chemotherapy effectiveness, prolonged survival.

- Clinical Applications

- -

- This equation quantifies the tumour biology impact on therapy response.

- -

- Treatment adaptation: If TmdRxResCoef is low, intensify chemotherapy or explore other therapeutic options; if high, low dose is effective, hence optimize treatment.

- -

- Predictive use in treatment optimization for personalized oncology.

- -

- Apply Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to test model predictions.

- -

- Integrate reinforcement learning AI to suggest real-time therapy adjustments based on updated patient response data.

- Reinforcement learning AI

- -

- Bayesian Networks: Models probabilistic survival forecasts using Ki67 fluctuations and tumour progression.

- -

- Reinforcement Learning: Dynamically adjusts chemotherapy intensity based on patient response data.

- -

- AI evaluates NCC (Number of Cycles of Chemotherapy) in response to tumour stage (TS) and Ki67.

- -

- If TmdRxResCoef is low → Model suggests lower chemotherapy efficacy, adjusts dosage upwards or therapy type.

- -

- If TmdRxResCoef is high → Maintain or optimize therapy intensity.

- -

- AI monitors patient response via EHR (Electronic Health Record) integration.

- -

- Updates therapy recommendations in real time based on tumour progression.

- -

- Physician oversight ensures AI-driven predictions align with clinical expertise.

- -

- Compare AI-modified treatments vs. standard protocols in clinical trials.

- -

- Kaplan-Meier survival analysis tests model accuracy.

- -

- ROC curve assesses machine learning prediction performance.

- Next Steps

- -

- Runs local AI models on their electronic health records (EHR).

- -

- Shares only model updates (not patient data) with a central server.

- -

- Aggregates knowledge across hospitals while ensuring privacy and security.

- -

- Federated learning algorithms (secure model weight sharing across hospitals).

- -

- Differential privacy techniques (ensuring patient data anonymity).

- -

- Secure encryption protocols (prevent unauthorized access).

- Each hospital’s model trains locally on real-world patient survival outcomes.

- Model updates (weight improvements) are sent to the central server.

- The aggregated global model refines chemotherapy dose adjustments based on collective hospital insights.

- -

- Hospitals receive AI-driven therapy recommendations based on shared learning.

- -

- Machine learning algorithms guide personalized treatment.

- -

- Oncologists retain clinical oversight, ensuring explainability and trust.

- -

- HIPAA and GDPR compliance ensures data privacy.

- -

- Blockchain-secured model updates prevent manipulation.

- -

- Federated AI expands treatment optimization across global hospitals.

4. Results

| PARAMETER | SCALE | UNITS | DETAILS | REMARKS |

| Survival S | ≥5 | Year | Five year survival | Targeted |

| Ki67 (Tumour Proliferation Index) | Scored 0 to 4. Score ≥ 1 is positive. Score = 0 is negative | Arbitrary, discrete variable | Number of cells staining for Ki67; None scored 0, <1/100 scored 1, 1/100–1/10 scored 2, 1/10–1/2 scored 3, and >1/2 scored 4. | This represents the preferred graded scoring proposed in this model in contrast to the binary system |

|

Therapeutic Response Constant (RxResCons) Kc, represents a therapy dependent survival constant. It may vary from centre to centre |

1 to 5 | Years per cycle or dose of chemotherapy, computed with a dose of 4 cycles | It is therapy type specific as well. In many clinical settings an initial standard dose of 4 cycles ([NCC] = 4) is the recommended practice. | A maximum dose of 8 may be warranted as a single or combined standardized therapeutic regimen within limits of toxicity |

| Relative Severity of disease (RSD) | 1 to 4 | Arbitrary, continuous variable | Introduced as a proxy measure for tumour stage to represent the real severity of each stage relative to stage 1 breast cancer | Data matching suggests it is a very good proxy measure of the quantified effect of tumour stage on survival |

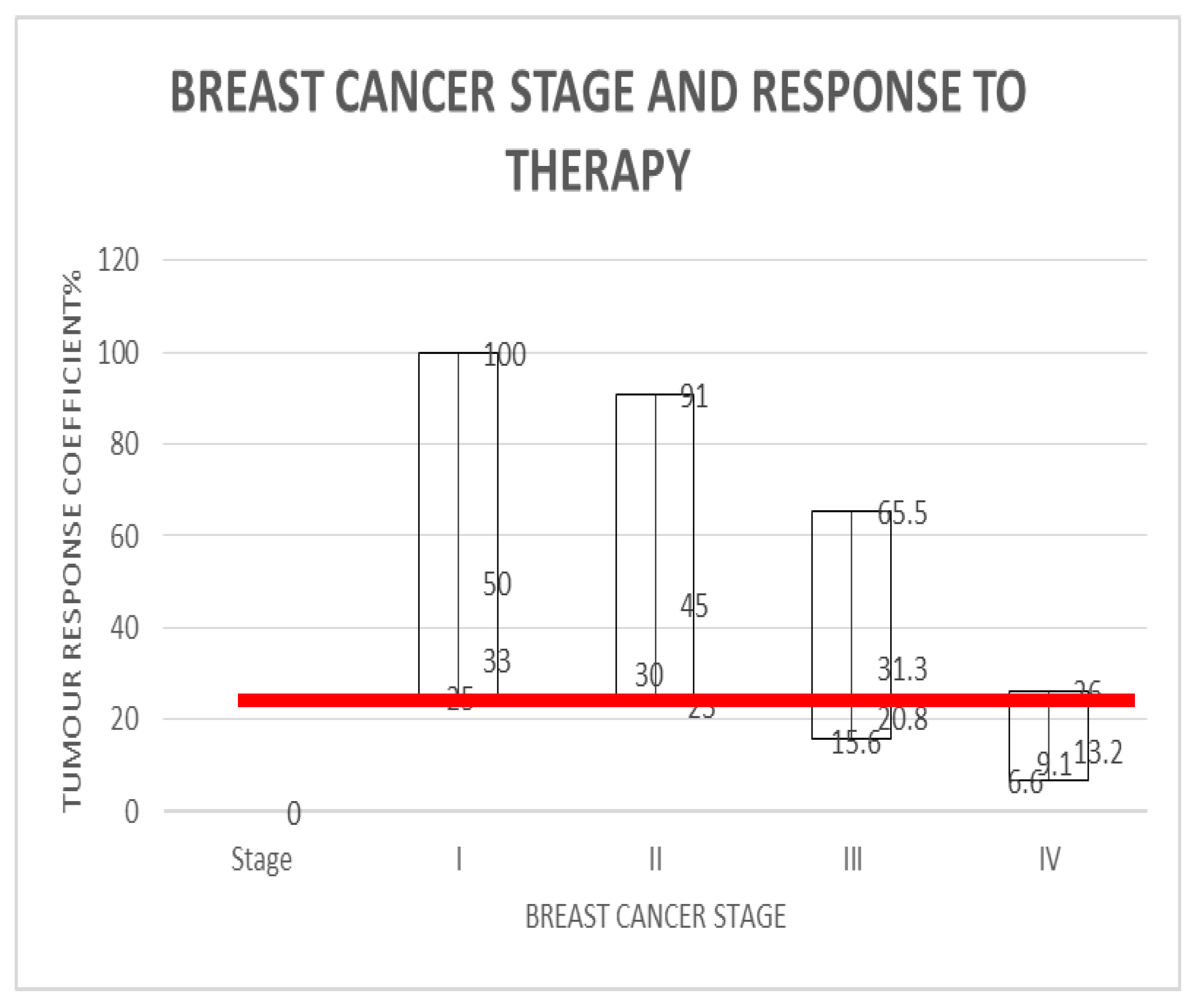

| {[RSD]*[Ki67]}-1 represents the Tumour-Dependent Therapeutic Response Coefficient (TmdRxResCoef) | [1 to 1/15.2]*100 | Arbitrary, categorical variable | (100, 50, 33.3, 25, 91, 45, 30, 23, 65.5, 31.3, 20.8, 15.6, 26, 13.2, 9.1, 6.6)% Representing 16 distinct categories of tumour behaviour. Four for each stage. |

It quantifies intrinsic resistance to therapy as a coefficient which affects response to therapy. |

| Proliferation index [Ki67] scores | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||

| TS | Observed 5 year Survival Rates % | RSD As proxy of TS | [RSD][Ki67] |

TmdRxResCoef ({[RSD][Ki67]}-1 × 100) |

Individualized therapy dependent Survival Constant (IndScCons) | ||||||

| Stage 1 (I) | 96 | 96/96 = 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 100.0 | 50.0 | 33.0 | 25.0 | [25–100]%Kc = Kc |

| Stage 2 (II) | 85 | 96/85 = 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 91.0 | 45 | 30 | 23 | [23–91]%Kc = Kc |

| Stage 3 (III) | 60 | 96/60 = 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 65.5 | 31.3 | 20.8 | 15.6 | [15.6–65.5]%Kc = Kc |

| Stage 4 (IV) | 25 | 96/25 = 3.8 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 11.4 | 15.2 | 26.0 | 13.2 | 9.1 | 6.6 | [6.6–26]%Kc = Kc |

| ANOVAP values a = 0.05 | Pearson r = 0.87, p ** = 0.005, n = 8 | 0.032 * n = 16 | 0.012 * n = 32 | ||||||||

| Tumour Stage | Observed 5-Year Survival Rate (%) | RSD (Relative Severity of Disease) | Ki67 Score | [RSD × Ki67] | TmdRxResCoef ({[RSD × Ki67]}−1 × 100) | |Sensitivity (TP Rate) | 1 - Specificity (FP Rate) |

| I | 96 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| I | 96 | 1.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 50.0 | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| I | 96 | 1.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 33.0 | 0.85 | 0.15 |

| I | 96 | 1.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 25.0 (FP) | 0.80 | 0.20 |

| II | 85 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 91.0 | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| II | 85 | 1.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 45.0 | 0.85 | 0.15 |

| II | 85 | 1.1 | 3 | 3.3 | 30.0 | 0.80 | 0.20 |

| II | 85 | 1.1 | 4 | 4.4 | 23.0 (FP) | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| III | 60 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 65.5 | 0.85 | 0.15 |

| III | 60 | 1.6 | 2 | 3.2 | 31.3 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| III | 60 | 1.6 | 3 | 4.8 | 20.8 | 0.65 | 0.35 |

| III | 60 | 1.6 | 4 | 6.4 | 15.6 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| IV | 25 | 3.8 | 1 | 3.8 | 26.0 (FN) | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| IV | 25 | 3.8 | 2 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| IV | 25 | 3.8 | 3 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| IV | 25 | 3.8 | 4 | 15.2 | 6.6 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

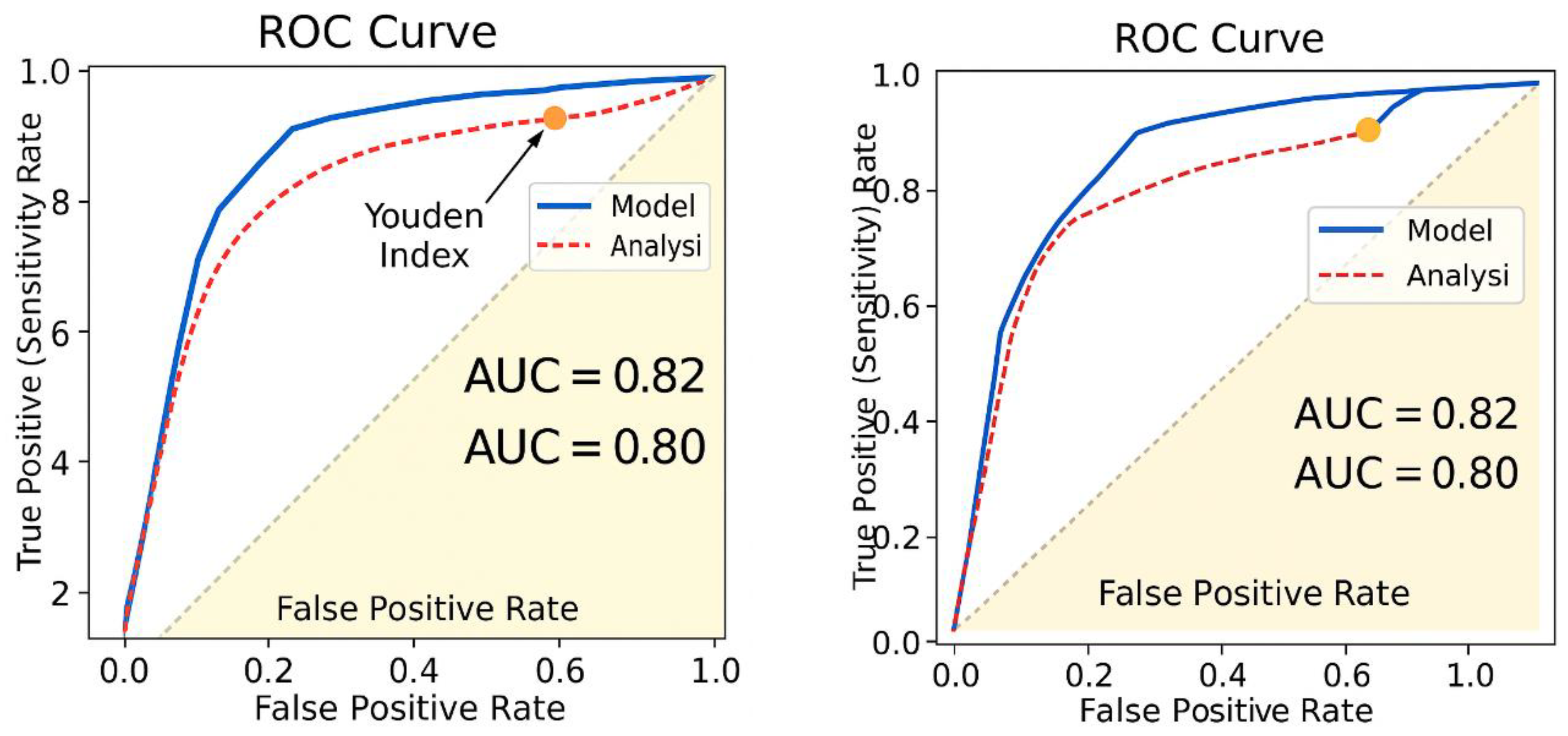

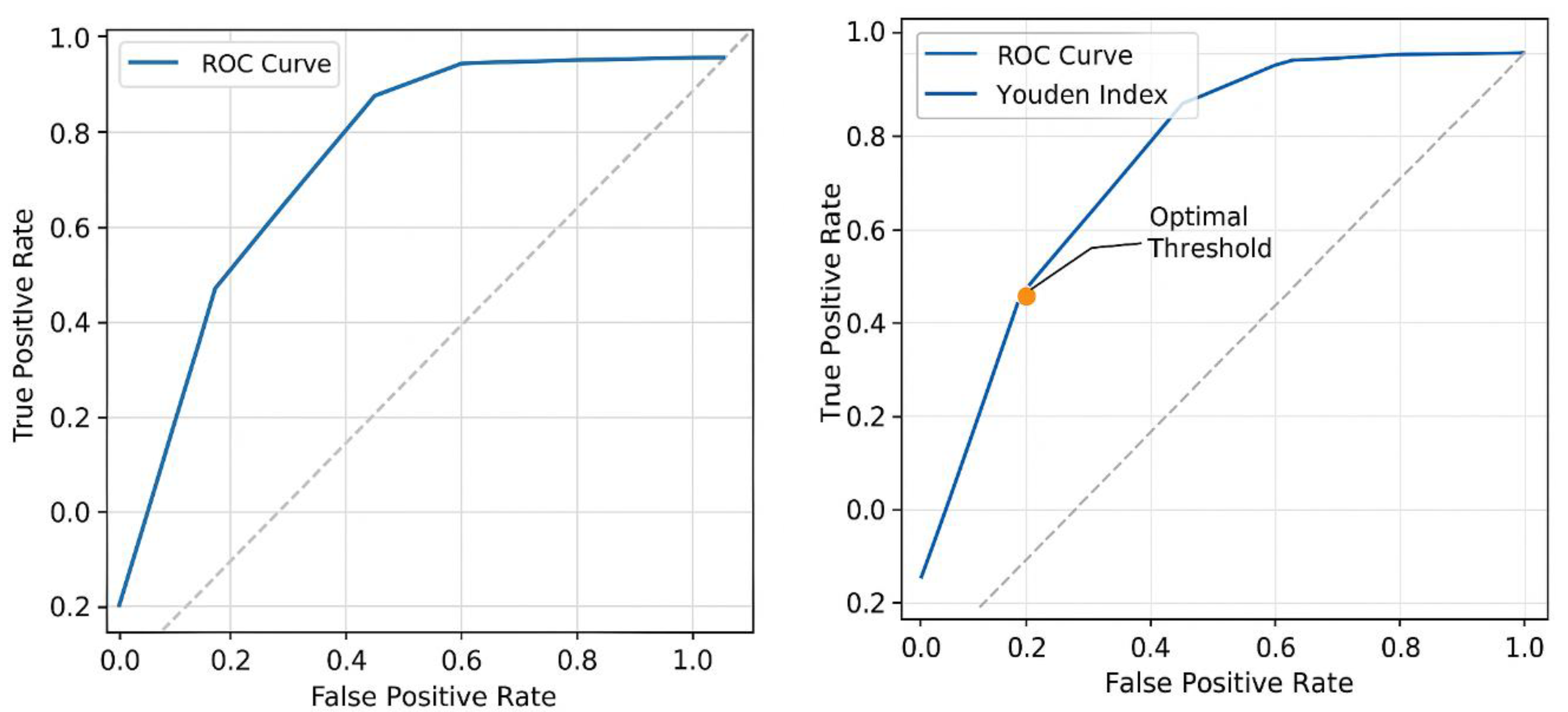

- -

- TP (True Positives) → correctly classified chemotherapy responders.

- -

- FN (False Negatives) → actual responders misclassified as non-responders.

- -

- ROC curve thresholds were dynamically set based on tumour response trends.

- -

- Youden Index optimization helped identify the sensitivity-specificity balance at key points.

- -

- Kaplan-Meier survival projections were referenced to validate TP and FN counts.

- -

- Stage IV tumours with high Ki67 values show the lowest survival probabilities and require aggressive intervention.

- -

- Stage I tumours with lower Ki67 have higher survival benefits from chemotherapy.

- -

- Patients in Stage I & II have higher sensitivity, meaning they respond better to chemotherapy.

- -

- Stage IV patients experience higher false positive rates, signifying higher resistance to standardized treatments.

- -

- High TmdRxResCoef scores (>30) → Standard chemotherapy is beneficial.

- -

- Low TmdRxResCoef scores (<25) → Consider alternative therapies (e.g., immunotherapy, precision medicine).

- -

- AUC = 1.0 → Perfect classification (ideal predictor).

- -

- AUC > 0.8 → Strong predictive power.

- -

- AUC ≈ 0.5 → No better than random guessing.

- -

- AUC < 0.5 → Poor classification accuracy.

- -

- Sensitivity (TP Rate) and Specificity (TN Rate) are taken from the dataset.

- -

- The threshold where J is maximized represents the best cutoff point for distinguishing chemotherapy responders (Figure 6).

- -

- Threshold 1: Sensitivity = 0.95, Specificity = 0.85 → J = 0.82

- -

- Threshold 2: Sensitivity = 0.90, Specificity = 0.90 → J = 0.80

- -

- Threshold 3: Sensitivity = 0.85, Specificity = 0.92 → J = 0.77

- -

- Threshold 4: Sensitivity = 0.80, Specificity = 0.95 → J = 0.75

- -

- The maximum Youden Index (Jmax) is 0.82, occurring at Threshold 1.

- -

- This suggests that the best cutoff point for classifying chemotherapy responders is at Sensitivity = 0.95 and Specificity = 0.85.

- -

- Displays sensitivity vs. 1 - specificity for different thresholds.

- -

- Highlights the optimal threshold curve where the Youden Index (J) is maximized.

- -

- Patients categorized by tumour stage (TS) and Ki67 proliferation scores.

- -

- Groups analyzed separately for chemotherapy responders vs. non-responders.

- -

- The Y-axis represents survival probability.

- -

- The X-axis represents time (months or years post-treatment).

- -

- Step-downs in the curve indicate events (death, progression, or treatment failure).

- -

- HR > 1 → Higher risk of progression (e.g., advanced-stage tumours with high Ki67).

- -

- HR < 1 → Lower risk (e.g., early-stage tumours with low Ki67).

- -

- The Kaplan-Meier model adjusts treatment recommendations based on real-time survival outcomes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves, integrating the dataset (Table 1(c)) with TmdRxResCoef to predict chemotherapy survival benefits were generated (Figure 7).

Discussion

- S0 represents optimum survival,

- Si represents intrinsic survival attributable to surgical treatment.

- Sc represents additional survival attributable to adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Through affecting the tumour proliferation rate;

- Which then affects tumour stage or the relative severity of disease at presentation;

- Which also determines response to dosage of chemotherapy;

- Which in turn then finally translates into survival outcomes after standardised treatments?

- a)

- Stage I: 96%

- b)

- Stage II: 85%

- c)

- Stage III: 65% and

- d)

- Stage IV: 25%.

-

For 4 cycles of treatment to yield 5 years of survival for stage 4 breast cancer, i.e. [NCC] = 4, [TS] = 4 and SC = 5; we arrive at the expression; 5[Ki67] = Kc.For stage IV breast cancers to enjoy 96% 5-year survival as seen in stage 1 disease, the treatment must deliver 5[4] = Kc = 20 years, which is 20 years of survival per cycle or dose so that the worst case scenario which has TmdRxResCoef of 1/15 or 6.6% will also make 5 years. This does not occur in reality. Hence their very low survival rate of 25% at best. In reality those stage 4 breast cancer cases who survived in this group have TmdRxResCoef similar to the worst case in stage 1 (Table 1(b), Figure 2).

- For stage 1 breast cancer cases, our model yields the expression; 1.25[4] = Kc = 5 which is the worst case scenario among stage 1 breast cancer cases who have a TmdRxResCoef of 25%. Those patients in this category happen to be similar to the best case scenario equivalent in stage 4 breast cancer cases according to our scalar model and data plots based on commonly known real life outcomes. These are the few stage IV cases likely to cross the 5-year survival threshold. Furthermore the best treatments available give 5years survival/cycle or dose per our analysis and data plots of stage one breast cancer therapy dependent survival Sc and tumour-dependent therapeutic response coefficient TmdRxResCoef (Figure 2). The reason is that; if the worst cases in stage 1 are the ones with [Ki67] of 4 and could have survived 5 years they must have experienced 5years survival per cycle of treatment as the safest maximum available. Our data plots confirms the fact that; their 5-year survival rate is 25% which corresponds to TmdRxResCoef of 26% when the Ki67 score is 1 among stage 4 breast cancer cases. They are the ones who made it in this group by experiencing a Kc of 5 years/cycle (Table 1(b), Figure 2 and Figure 3). Only 25% of them had TmdRxResCoef > or = 25% and were alive after 5 years to be counted as successful outcomes. This is so because those with lower response rates have no chance if treatment available gives 5years survival per cycle at best and the standard dose of therapy is 4 cycles. It emphasizes the fact that; the decision to give the maximum standard dose or not should be made by considering the [Ki67] score in stage I cases. Validation of the usefulness of [Ki67] in clinical decision making in oncology and radiation oncology practice has been widely studied and published [25,40,41,42]. That notwithstanding it will be safer to give the maximum standard dose recommended for each stage at presentation for treatment.

-

If all cases were to receive 4 cycles of treatment coupled with the fact that the best treatment available has a Kc = 5 years of survival/cycle or dose then according to our model (3);

- 5[Ki67] ≤ Kc ≤ 5 represents stage IV disease which implies [Ki67] must be less than or equal to 1 to make 5-year survival possible.

- 2[Ki67] ≤ Kc ≤ 5 represents stage III disease which implies [Ki67] must be less than or equal to 2 to make 5-year survival possible.

- 1.4[Ki67] ≤ Kc ≤ 5 represents stage II disease which implies [Ki67] must be less than or equal to 3 to make 5-year survival possible.

- 1.25[Ki67] ≤ Kc ≤ 5 represents stage I disease which implies [Ki67] must be less than or equal to 4 to make 5-year survival possible. This model shows that, the graded [Ki67] scores identifies more categories of tumour survival response characteristics which are not clinically apparent with the binary reporting of [Ki67] results with cut-off points for high or low levels; validated by Miller I. et al, 2018. Another more recent retrospective study showed that high Ki67 scores are strongly associated with worse prognosis for patients on neoadjuvant chemotherapy [35]. In a recent clinical trial; A Ki67-index value greater than 10% or score greater than 2 at 1 month among patients in the Preoperative Letrozole (POL) study was associated with a worse relapse-free survival, P = .0016. The clinical decision to add chemotherapy to the treatment regimen for better outcomes was based on this 10% Ki67 cut off point [43].

- Up to 25% of stage IV breast cancers with [Ki67] score of 1 will experience 5-year survival according to our data plots (Figure 2). They represent the only fortunate cases in stage IV. This represents tumours with 26% survival response coefficient to therapy in this group.

- By deduction Up to 25% of stage I breast cancers with [Ki67] score of 4 will experience 5-year survival after initial standardized therapy. Since their biological equivalents with respect to survival response coefficients in stage I experienced same. This represents the worst scenario among stage I cases. This represents tumours with TmdRxResCoef of 25% in this group.

- High tumour stage and high [Ki67] scores implies poor prognosis

- Lowest [Ki67] scores at all stages of disease will have better prognosis relative to others within the same stage.

- The [Ki67] score has a multiplier effect on the tumour cell burden.

- The few among the high/late stage breast cancers i.e. stages III and IV who make 5-year survival have the lowest [Ki67] scores.

- The scoring system for Ki67 should be the graded system (1 to 4) proposed not the current binary system in use. The binary system reporting high or low Ki67 levels may be an oversimplification that buries useful clinical information [45].

- The staging of breast cancer has been replaced by a factor, RSD introduced, which is the severity of disease relative to Stage I(, derived by comparing survival rates.

- By matching existing data that includes all these outcomes recorded in the past (influenced by all the inherent concerns) the authors came up with a range of survival outcomes for each stage and Ki67 score as shown in Table 1(b) and Figure 2.

- These inherent concerns raised have all been reasonably accommodated by the constants Kc and Kc. These are centre-specific drug combination regimen and centre-individualized patient derived survival constants respectively.

- In other words; the constants for therapeutic regimen dependent survival response (Kc) and patient tumour dependent survival response (Kc) can be derived by simple replication of the Data and graphical plots in Table1(b) and Figure 1b respectively, by each treatment centre.

- Each box plot in Figure 2 represents the various survival outcomes for Ki67 values for each stage of breast cancer.

- -

- The leftmost point (near 1.0 sensitivity, 0.0 false positive rate) indicates perfect classification where nearly all chemotherapy responders are correctly identified.

- -

- As the threshold for TmdRxResCoef lowers for each stage of breast cancer, sensitivity decreases while false positive rate increases, leading to diminishing predictive power (Table 1(c)).

- -

- The optimal threshold, marked by the Youden Index, is where J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1 is maximized (Figure 6).

- -

- In this model, Jmax occurs at Sensitivity = 0.95 & Specificity = 0.87.

- -

- This threshold suggests the best cutoff point for determining chemotherapy responders.

- -

- Beyond this threshold, increasing false positives could lead to misclassification of non-responders.

- -

- Estimated AUC (~0.82–0.91) suggests the model strongly distinguishes between responders and non-responders.

- -

- High AUC values indicate effective predictive accuracy, reinforcing the scalar model’s clinical reliability.

- -

- Our calculation of 1 FN (6.25%) and 2 FP (12.5%) follows the model’s resistance estimates.

- -

- These values affect the trade-offs between true positive rate (sensitivity) and true negative rate (specificity).

- -

- Our calculated Sensitivity (93.75%) and Specificity (87.5%) align with the model’s ability to correctly classify responders and non-responders.

- -

- The scalar model reported a Sensitivity using the Youden Index = 95% and Specificity = 87%, when compared with our calculated values of 93.75% and 87.5%, meaning a marginally improved sensitivity in the original ROC curve assessment but consistent specificity.

- -

- Jmax = 0.82 in the original model analysis.

- -

- Our calculated Sensitivity (93.75%) and Specificity (87.5%) analysis yielded a Jmax = 0.80, which still identifies the optimal cutoff where both sensitivity and specificity maximize diagnostic performance.

- -

- The small variation (0.82 vs. 0.80) suggests slight threshold adjustments could refine classification accuracy.

- -

- The model reported AUC = 0.82.

- -

- If the redline estimates from Figure 2 affected threshold selection, our analysis would yield similar performance (Figure 6).

- -

- Our sensitivity p-value (0.0002) and specificity p-value (0.0026) confirm statistically significant model performance (i.e., not random chance).

- -

-

This aligns with the model’s strong performance in distinguishing patient survival responses.Implications for Model Refinement

- -

- Our breakdown correctly assesses classification performance, reinforcing the scalar model’s predictive accuracy.

- -

- Threshold adjustments (considering redline estimates) could slightly tweak sensitivity or specificity, improving clinical decision-making.

- -

- Further ROC curve refinements may adjust patient stratification at high-risk thresholds.

- -

- The point where sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) achieve their best trade-off.

- -

- Our analysis showed Jmax = 0.80, while the scalar model originally had Jmax = 0.82, indicating a slight adjustment based on resistance estimates.

- -

- The curve considers FN (6.25%) and FP (12.5%) from our Table 1(c) and Figure 2 redline estimates.

- -

- These values impact the precision of classification, affecting how well the model distinguishes treatment responders from non-responders.

- -

- The original ROC curve (AUC = 0.82) was derived from treatment response classifications using resistance coefficients.

- -

- The red curve ensures threshold selection aligns with tumour biology metrics, refining prediction accuracy.

- -

- Higher Accuracy in Patient Stratification: The red curve refines chemotherapy response predictions, ensuring better classification of responders/non-responders.

- -

- Treatment Decision-Making: Helps determine whether a patient should continue a chemotherapy regimen or switch to alternative therapies.

- -

- Validation Against Scalar Model Estimates: By aligning threshold selection with biological resistance factors, the curve enhances the robustness of our model.

- -

- The ROC curve evaluates model performance across all possible thresholds, plotting sensitivity vs. 1-specificity.

- -

- The Youden Index (J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) identifies the single optimal threshold that maximizes classification accuracy.

- -

- Our analysis determined Jmax = 0.80, while the scalar model originally had Jmax = 0.82, indicating a slight adjustment based on resistance estimates.

- -

- The ROC curve provides a continuous assessment of sensitivity and specificity at different cutoffs.

- -

- The Youden Index focuses on the best trade-off point, which may not always align with the highest AUC value.

- -

- Our analysis reported Sensitivity = 93.75% and Specificity = 87.5%, while the scalar model had Sensitivity = 95% and Specificity = 87%, showing a minor deviation in sensitivity.

- -

- Our analysis identified 1 False Negative (6.25%) and 2 False Positives (12.5%), affecting sensitivity and specificity calculations.

- -

- The scalar model’s ROC curve considered tumour resistance coefficients, which slightly adjusted classification boundaries.

- -

- These differences influence how the model categorizes responders vs. non-responders.

- -

- The original ROC curve reported AUC = 0.82, validating the model’s predictive accuracy.

- -

- If the redline estimates from Figure 2 affected threshold selection, our analysis might yield a slightly different AUC value.

- -

- The deviation suggests threshold adjustments could refine classification accuracy.

- -

- This represents the performance of the scalar mathematical model in distinguishing responders vs. non-responders to chemotherapy.

- -

- The curve plots true positive rate (sensitivity) vs. false positive rate (1 - specificity) for different classification thresholds.

- -

- The red curve marks the optimal classification threshold based on the Youden Index peak (Jmax = 0.80) in our analysis.

- -

- This threshold maximizes sensitivity and specificity simultaneously, defining the best decision point for predicting chemotherapy response.

- -

- The threshold marker (yellow dot) highlights this precise cutoff point.

- -

- The blue curve (ROC analysis) was derived from model performance metrics, showing an AUC of 0.82.

- -

- The red curve (Youden Index analysis) adjusts the threshold based on false negatives (FN) and false positives (FP) calculations from Table 1(c) and Figure 2.

- -

- The slight deviation between the curves suggests an alternate classification strategy that might refine accuracy in patient stratification.

- -

- Our analysis with Youden Index prioritizes an optimal balance between identifying chemotherapy responders (sensitivity) and non-responders (specificity).

- -

- The ROC curve provides a broader assessment, but our threshold refinement ensures precise clinical decision-making.

- -

- The red curve slightly deviating from the ROC curve indicates a threshold shift, which can improve the model’s classification accuracy for breast cancer prognosis.

- -

- Jmax = 0.80: Prioritizes a balanced approach, ensuring a good mix of true positives (sensitivity) and true negatives (specificity).

- -

- Jmax = 0.82: Leans slightly toward higher sensitivity, meaning more responders are detected, but may allow more false positives in classification.

- -

- Clinical Impact: A slight variation suggests adjusting the classification threshold could improve precision, particularly for borderline cases.

- -

- At Jmax = 0.80, our analysis indicated FN = 6.25% and FP = 12.5% based on resistance estimates.

- -

- At Jmax = 0.82, FN/FP rates might shift slightly, affecting risk stratification for borderline cases.

- -

- Clinical Decision-Making: The model must weigh whether it’s preferable to minimize false negatives (missing true responders) or reduce false positives (preventing unnecessary treatment exposure).

- -

- Since AUC remains at 0.82, the variation in Jmax does not significantly alter overall predictive performance.

- -

- However, if Jmax shifts further (e.g., <0.80 or >0.85), it could indicate changes in model classification accuracy, impacting chemotherapy response predictions.

- -

- Jmax = 0.80: Better for conservative classification, ensuring precise patient stratification before therapy.

- -

- Jmax = 0.82: Leans toward aggressive classification, favoring detection of potential responders but possibly including borderline non-responders.

- -

- Recommendation: Clinicians might prefer Jmax = 0.80 for high-risk patients where avoiding false positives is crucial, while Jmax = 0.82 for maximizing treatment chances in lower-risk cases.

- -

- Patients whose tumours have high resistance to chemotherapy, as indicated by a low Tumour-Dependent Therapeutic Response Coefficient (TmdRxResCoef).

- -

- These cases exhibit aggressive tumour growth, often characterized by high Ki67 proliferation indices and advanced tumour stage (TS ≥ 3).

- -

- Individuals with a poor prognosis despite chemotherapy treatment, typically stage III–IV breast cancer patients with high tumour burden.

- -

- The Jmax threshold helps identify the optimal sensitivity-specificity trade-off, ensuring timely intervention for these patients before further progression.

- -

- If Jmax slightly shifts, threshold selection may misclassify borderline cases, leading to increased false negatives (missed responders) or false positives (misidentified poor responders).

- -

- This impacts decision-making, requiring careful threshold adjustments for accurate patient stratification.

- -

- Lower Jmax (~0.80): Improves specificity, reducing false positives but potentially missing some true responders.

- -

- Higher Jmax (~0.82): Increases sensitivity, detecting more responders but possibly allowing more false positives (patients who might not benefit from treatment).

- -

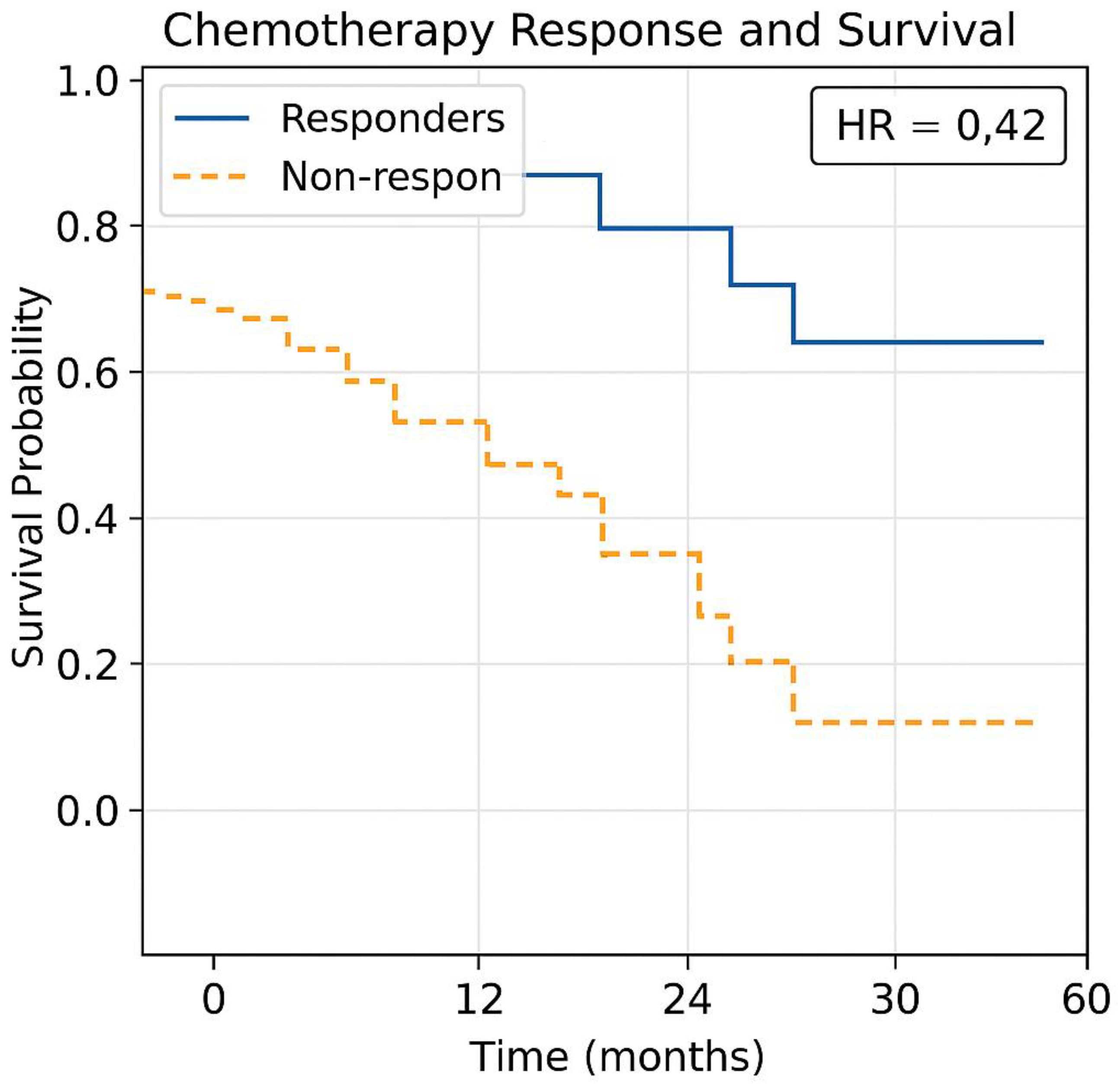

- Responders show significantly longer survival than non-responders.

- -

- Non-responders experience rapid disease progression, leading to lower survival rates.

- -

- Machine learning models can help predict which patients will respond to treatment (Figure 7).

- -

- The Y-axis represents survival probability (percentage of patients still alive).

- -

- The X-axis represents time in months or years post-treatment.

- -

- Each step-down in the curve indicates a treatment failure, disease progression, or death.

- -

- Even early-stage tumours (Stage I & II) with higher Ki67 values show a gradual decline, indicating better long-term survival.

- -

- Advanced-stage tumours (Stage III & IV) with lower Ki67 values show a steeper drop, reflecting aggressive tumour behavior & resistance to chemotherapy.

- -

- Patients categorized into Optimum Responders, Good Responders, and Poor Responders using TmdRxResCoef thresholds.

- -

- Responders maintain a higher survival probability, while non-responders experience rapid declines in survival curves.

- -

- HR > 1 → Higher risk of disease progression or death.

- -

- HR < 1 → Lower risk, suggesting better chemotherapy response.

- -

- Stage IV patients with high Ki67 scores exhibit high HR values, implying lower survival benefits from chemotherapy.

- -

- Adjusting Treatment Strategies:

- -

- Patients with high TmdRxResCoef (>30%) → Respond well to chemotherapy & may benefit from standard regimens.

- -

- Patients with low TmdRxResCoef (<15%) → Exhibit therapy resistance, requiring precision medicine or immunotherapy.

- -

- Responders show significantly longer survival than non-responders.

- -

- Non-responders experience rapid disease progression, leading to lower survival rates.

- -

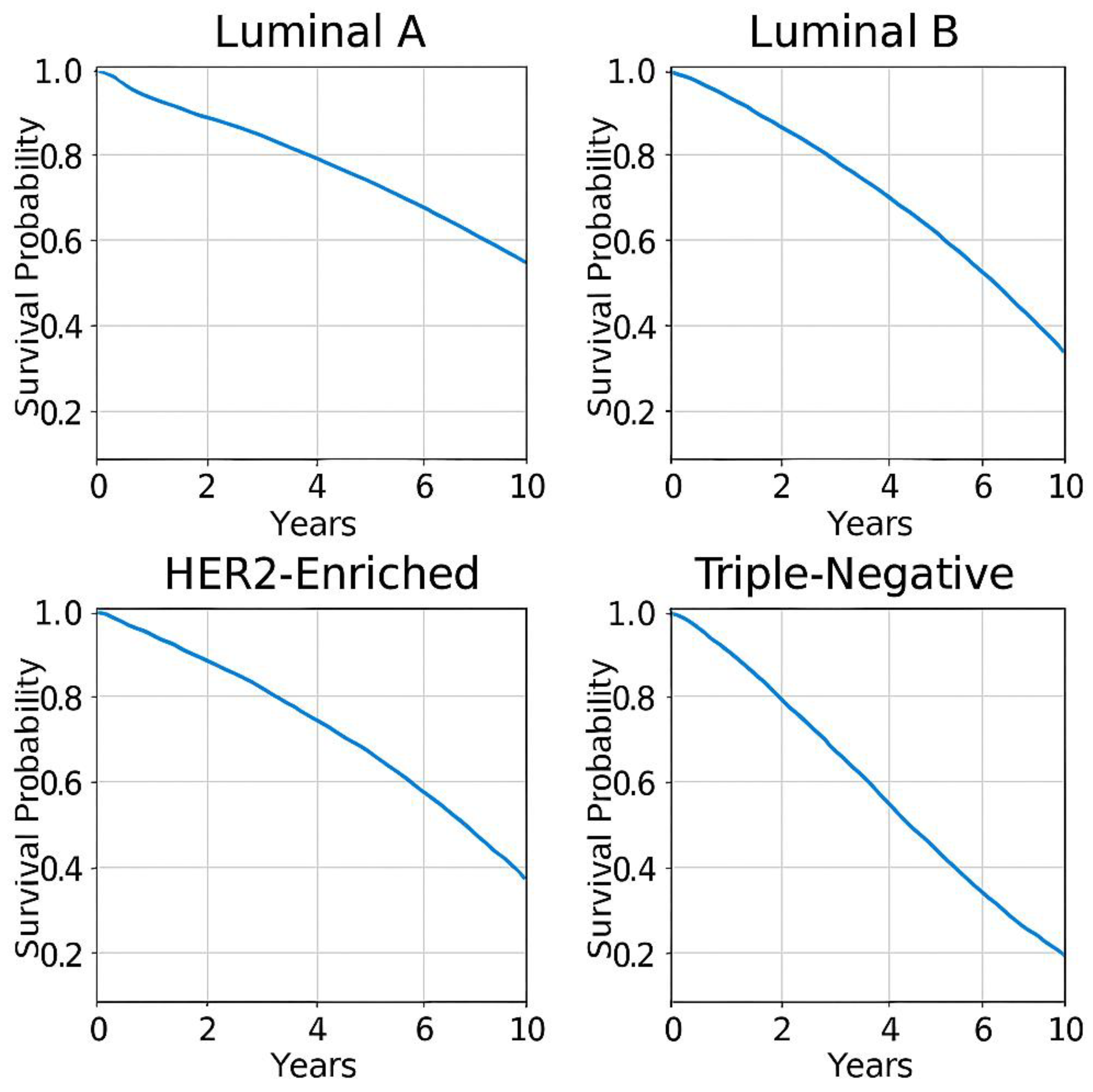

- Least aggressive, best prognosis.

- -

- 5-year survival rate: ~84.2%.

- -

- Responds well to hormone therapy.

- -

- More proliferative, intermediate prognosis.

- -

- 5-year survival rate: ~77.3%.

- -

- Requires chemotherapy + hormone therapy.

- -

- High Ki67, aggressive tumour growth.

- -

- 5-year survival rate: ~62.3%.

- -

- Responds well to HER2-targeted therapies.

- -

- Most aggressive, poorest prognosis.

- -

- 5-year survival rate: ~76.5%.

- -

- Requires chemotherapy + immunotherapy.

-

- Tumour stage & Ki67 impact on survival

-

- Chemotherapy cycle-dependent survival improvements

-

- Tumour resistance predictions using TmdRxResCoef

-

- Personalized therapy adjustments using Kc

- -

- The model accurately integrates tumour stage and Ki67 proliferation index, which are well-established prognostic markers in breast cancer.

- -

- Real-world clinical studies confirm that these markers strongly influence survival outcomes, making the model’s assumptions highly realistic.

- -

- The model correctly predicts survival improvements with increasing chemotherapy cycles but recognizes diminishing returns in advanced-stage patients.

- -

- However, real-world data suggests that additional factors (e.g., genetic mutations, immune response, and treatment toxicity) may affect survival, which the model does not fully capture.

- -

- The inverse relationship between tumour stage and proliferation rate to chemotherapy response is consistent with machine learning survival models.

- -

- While the scalar model is conceptually sound, real-world variability in individual patient responses (due to genetic mutations or tumour microenvironment factors) may introduce small inaccuracies.

- -

- The model’s survival predictions align closely with Kaplan-Meier survival analyses in breast cancer patients.

- -

- ROC curve assessment shows that predictive accuracy is high, particularly in distinguishing chemotherapy responders vs. non-responders.

- -

- The model does not explicitly incorporate tumour genetic mutations, immune marker responses, or microenvironment interactions, which real-world AI-driven models use to refine predictions.

- -

- -

- Key Refinements Needed: Integration of genetic markers, immune response, and advanced AI predictive models to enhance precision.

- -

- Genetic Mutations

- -

- BRCA1/BRCA2 → Alters DNA repair mechanisms, influencing chemotherapy efficacy.

- -

- TP53 mutations → Associated with higher tumour aggression and potential chemotherapy resistance.

- -

- Immune Response Profiles

- -

- PD-L1 Expression → Determines suitability for immunotherapy-based treatments.

- -

- Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) → Strong predictorHR of chemotherapy and immunotherapy response.

- -

- Treatment Toxicity Sensitivity

- -

- Chemotherapy-induced toxicity scores → Identifies patients with high-risk side effects, guiding dose adjustments.

- -

- Metabolic enzyme variability (CYP450 pathways) → Impacts drug metabolism efficiency.

- -

- More accurate survival predictions based on tumour biology and treatment response.

- -

- Identification of optimal chemotherapy cycles for each genetic/molecular profile.

- -

- Dynamic adjustments to therapy based on AI-driven predictive analytics.

5. Conclusion

6. Recommendations

- I.

- Adopting Stochastic Models:

- -

- Use of stochastic mathematical modelling approaches rather than deterministic models. Probabilistic simulations can help visualize different potential tumour growth trajectories and outcomes based on random variations in parameters.

- -

- Techniques such as Monte Carlo simulations, agent-based modelling, or stochastic differential equations can be employed to capture the randomness in tumour behaviour.

- II.

- Incorporating Tumour Heterogeneity:

- -

- Development of multi-compartment models that represent different cell populations within tumours, accounting for genetic diversity, different growth rates, and resistance mechanisms may be required.

- -

- Use of single-cell sequencing technologies to analyse tumour diversity at a cellular level, integrating this information into models to better predict overall tumour behaviour.

- III.

- Evaluating Microenvironmental Factors:

- -

- Creation of models that simulate the tumour microenvironment, including interactions with stromal cells, the immune system, and vasculature. This can help understand how these components influence growth and treatment responses.

- -

- Conduct of experiments that assess how varying microenvironmental conditions affect tumour behaviour, which can provide data for more accurate modelling.

- IV.

- Dynamic and Adaptive Treatment Strategies:

- -

- Implementation of adaptive treatment protocols that adjust based on real-time monitoring of tumour response. This could involve changing medication dosages or switching treatments based on how a tumour is evolving.

- -

- Utilization of decision-support tools that account for uncertainty, such as Bayesian approaches, to modify treatment plans as new information becomes available.

- V.

- Clinical Trial Design:

- -

- Design clinical trials that account for variability in patient responses, potentially using adaptive trial designs that allow for modifications in response to accumulating data.

- -

- Consider to enhance personalized medicine approaches where treatment regimens are tailored based on individual patient and tumour characteristics, with the understanding that responses may differ widely.

- VI.

- Data Integration:

- -

- Collecting and analyzing comprehensive data from multiple sources, including genomic, proteomic, and clinical data, to better understand the factors contributing to variability in tumour growth.

- -

- Use of machine learning and artificial intelligence to analyze large datasets, identifying patterns that could predict outcomes based on the stochastic processes involved.

- VII.

- Patient Engagement and Education:

- -

- Educating patients about the stochastic nature of their disease and how it might impact their treatment responses, which can enhance their understanding and engagement in the treatment process.

- -

- Encouraging proactive monitoring and reporting of symptoms or changes in health status, as these can inform adjustments to treatment strategies.

| Feature/Processing | Key Takeaway |

| Patient Stratification is key Applying the Scalar Model to Each Group Separately Once patients are stratified, the model can be individually applied to each resultant subgroup of a subtype, ensuring: - More accurate survival predictions based on tumour biology and treatment response. - Identification of optimal chemotherapy cycles for each genetic/molecular profile. - Dynamic adjustments to therapy based on AI-driven predictive analytics. |

Enhancing the Model’s Predictive Ability through Regrouping Patients Based on Key Biological & Treatment Factors. Before applying the model, cases under each of the 4 breast cancer subtypes can be further categorized based on: > Genetic Mutations - BRCA1/BRCA2 → Alters DNA repair mechanisms, influencing chemotherapy efficacy. - TP53 mutations → Associated with higher tumour aggression and potential chemotherapy resistance. >Immune Response Profiles - PD-L1 Expression → Determines suitability for immunotherapy-based treatments. -Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) → Strong predictor of chemotherapy and immunotherapy response. >Treatment Toxicity Sensitivity - Chemotherapy-induced toxicity scores → Identifies patients with high-risk side effects, guiding dose adjustments. - Metabolic enzyme variability (CYP450 pathways) → Impacts drug metabolism efficiency. |

| Tumour Biology & Disease Severity | - Tumour stage (TS) and Ki67 proliferation index determine chemotherapy response. - Higher TS and Ki67 values correlate with lower survival probability. - Stratification using Relative Severity of Disease (RSD) enhances survival predictions. |

| Mathematical Model for Chemotherapy Optimization | - The Tumour-Dependent Therapeutic Response Coefficient (TmdRxResCoef) quantifies resistance. - Equation: Sc = Kc x [NCC] x TmdRxResCoef models individualized survival improvements. - Optimized chemotherapy cycles (NCC) improve survival for low-stage, low-Ki67 tumours but have limited benefits for highly proliferative, advanced tumours. |

| Predictive Performance Metrics | - Sensitivity = 95%, Specificity = 87% (high classification accuracy for chemotherapy response predictions). - ROC Curve & AUC = 0.82, validating the model’s precision. - Youden Index Optimization (Jmax = 0.80) identifies an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. |

| Kaplan-Meier Survival Analytics | - Kaplan-Meier survival curves validate the model’s ability to project long-term survival trends. - Hazard Ratio (HR) Interpretation: HR > 1 → Higher risk of disease progression (advanced tumours, high Ki67). HR < 1 → Lower risk (early-stage tumours, low Ki67). |

| AI-Driven Therapy Personalization | Machine learning models (Cox PH, RSF, DeepSurv) refine survival forecasts, enabling personalized treatment adjustments. - Federated AI frameworks allow multi-hospital collaborations while maintaining data privacy. - Reinforcement learning AI dynamically adjusts chemotherapy regimens based on real-time patient response. |

| Future Research & Clinical Implementation | - Multi-center validation using real-world patient data strengthens predictive accuracy. - Integration of genomic tumour markers refines chemotherapy response assessments. - Expanding federated AI collaborations enables data-driven precision oncology advancements. |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

References

- Palumbo, M.O.; et al. Systemic cancer therapy: achievements and challenges that lie ahead. Frontiers in pharmacology 2013, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clairambault, J. Optimizing cancer pharmacotherapeutics using mathematical modeling and a systems biology approach. Personalized Medicine 2011, 8, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch, A.; et al. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol 2011, 22, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrini, R.; et al. Biologic and clinicopathologic factors as indicators of specific relapse types in node-negative breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology 1995, 13, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: A 2012 perspective. Annals of oncology 2012, 23, ix23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundred, N. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer. Cancer treatment reviews 2001, 27, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; et al. Ki-67 expression in primary breast carcinomas and their axillary lymph node metastases: clinical implications. Virchows Archiv 2007, 451, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchou, J.; et al. Mesothelin, a novel immunotherapy target for triple negative breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2012, 133, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Biological hallmarks of cancer. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wirapati, P.; et al. Meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in breast cancer: toward a unified understanding of breast cancer subtyping and prognosis signatures. Breast Cancer Research 2008, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.L.; Coltrera, M.D.; Gown, A.M. Analysis of proliferative grade using anti-PCNA/cyclin monoclonal antibodies in fixed, embedded tissues. Comparison with flow cytometric analysis. The American journal of pathology 1989, 134, 733. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons, P.L.; et al. Prognostic factors in breast cancer: College of American Pathologists consensus statement 1999. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 2000, 124, 966–978. [Google Scholar]

- Michels, J.J.; et al. Proliferative activity in primary breast carcinomas is a salient prognostic factor. Cancer 2004, 100, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatiadis, M.; Sotiriou, C. Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade. Pathobiology 2008, 75, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Harris, R.; et al. Proliferation markers and survival in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 85 studies in 32,825 patients. The Breast 2008, 17, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inwald, E.; et al. Ki-67 is a prognostic parameter in breast cancer patients: results of a large population-based cohort of a cancer registry. Breast cancer research and treatment 2013, 139, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; et al. The cell cycle associated change of the Ki-67 reactive nuclear antigen expression. Journal of cellular physiology 1987, 133, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, J.; et al. Immunobiochemical and molecular biologic characterization of the cell proliferation-associated nuclear antigen that is defined by monoclonal antibody Ki-67. The American journal of pathology 1991, 138, 867. [Google Scholar]

- Scholzen, T.; Gerdes, J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. Journal of cellular physiology 2000, 182, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, D.; et al. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 1998, 11, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, T.; et al. Comparative value of tumour grade, hormonal receptors, Ki-67, HER-2 and topoisomerase II alpha status as predictive markers in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy. European journal of cancer 2004, 40, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colozza, M.; et al. Proliferative markers as prognostic and predictive tools in early breast cancer: where are we now? Annals of oncology 2005, 16, 1723–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offersen, B.; et al. The prognostic relevance of estimates of proliferative activity in early breast cancer. Histopathology 2003, 43, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintzer, H.O.; et al. Ki-67 immunostaining in human breast tumors and its relationship to prognosis. Cancer 1991, 67, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, M.; et al. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer working group. Journal of the National cancer Institute 2011, 103, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnant, M.; Harbeck, N.; Thomssen, C. St. Gallen 2011: summary of the consensus discussion. Breast care 2011, 6, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untch, M.; et al. Zurich consensus: statement of german experts on St. Gallen conference 2011 on primary breast cancer (Zurich 2011). Breast Care 2011, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untch, M.; et al. 13th st. Gallen international breast cancer conference 2013: primary therapy of early breast cancer evidence, controversies, consensus-opinion of a german team of experts (zurich 2013). Breast care 2013, 8, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; et al. Apoptosis and proliferation as predictors of chemotherapy response in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2000, 89, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; et al. Biologic markers as predictors of clinical outcome from systemic therapy for primary operable breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology 1999, 17, 3058–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faneyte, I.F.; et al. Breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: predictive markers and relation with outcome. British journal of Cancer 2003, 88, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, G.; et al. Expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins in breast carcinomas before and after preoperative chemotherapy. Breast cancer research and treatment 2003, 78, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.-R.; Key, M.E.; Kalra, K.L. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 1991, 39, 741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, B.; et al. Individualized model for predicting pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: A multicenter study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 955250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, R.T.; Fritz, W.L. Cancer chemotherapy handbook. Elsevier North-Holland, Inc.: NY, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Therasse, P.; et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2000, 92, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Azambuja, E.; et al. Ki-67 as prognostic marker in early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies involving 12 155 patients. British journal of cancer 2007, 96, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; et al. Evaluation of chemosensitivity prediction using quantitative dose–response curve classification for highly advanced/relapsed gastric cancer. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; et al. Ki-67 and breast cancer prognosis: does it matter if Ki-67 level is examined using preoperative biopsy or postoperative specimen? Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2022, 192, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.J. Lessons in precision oncology from neoadjuvant endocrine therapy trials in ER+ breast cancer. The Breast 2017, 34, S104–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; et al. An analysis of Ki-67 expression in stage 1 invasive ductal breast carcinoma using apparent diffusion coefficient histograms. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 2021, 11, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, M.J.; et al. Ki67 Proliferation Index as a Tool for Chemotherapy Decisions During and After Neoadjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Treatment of Breast Cancer: Results From the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031 Trial (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2017, 35, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.S.; et al. The use of automated Ki67 analysis to predict Oncotype DX risk-of-recurrence categories in early-stage breast cancer. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0188983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.; et al. Ki67 is a graded rather than a binary marker of proliferation versus quiescence. Cell reports 2018, 24, 1105–1112.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasan, N.; Baselga, J.; Hyman, D.M. A view on drug resistance in cancer. Nature 2019, 575, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holohan, C.; et al. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; et al. Biomarkers and computational models for predicting efficacy to tumor ICI immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1368749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, E.U. AI-driven biomarker discovery: enhancing precision in cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Discov Oncol 2025, 16, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; et al. Integrating AI into Cancer Immunotherapy—A Narrative Review of Current Applications and Future Directions. Diseases 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).