1. Introduction

The catalytic oxidation of styrene is an environmentally friendly path for the production of benzaldehyde, which is an important intermediate for the production of many fine compounds and commodity chemicals [

1]. Various catalysts differ in the conversion and selectivity of benzaldehyde, styrene epoxide, phenylacetaldehyde, 1-phenylethane-1,2-diol, benzoic acid, phenylacetaldehyde and other oxidation products. The development of sustainable and effective catalytic systems for the production of benzaldehyde using green oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide, is highly significant. For the rational design of efficient catalysts, we must know the corresponding reaction mechanisms. Redox-active ligands can contribute to it by storing and providing electrons, modifying the Lewis acidity of the metal, and assisting the formation/breaking of substrate bonding.

The catalytic styrene oxidation is assumed to be a simple reaction procedure, but its details require further systematic research. Knowledge of its important details is crucial for the development of new catalytic systems. Despite intense studies of the catalyzed oxidation of alkenes with hydrogen peroxide, no generally accepted mechanism of these reactions is known.

The Wacker process [

2] is an industrial homogeneous catalytic oxidation of ethylene to acetaldehyde in the presence of PdCl

2 and CuCl

2 that was considered to be well understood. Its mechanism is based on an active intermediate [PdCl

2(C

2H

4)(H

2O)], with π-bonded ethylene to Pd(II) central atom.

However, other catalytic studies using transition metal complexes with multidentate ligands suppose that the intermediate M-O-O-H (M is the metal center) is formed and the O-O bond is activated so that the alkene can react with it [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]

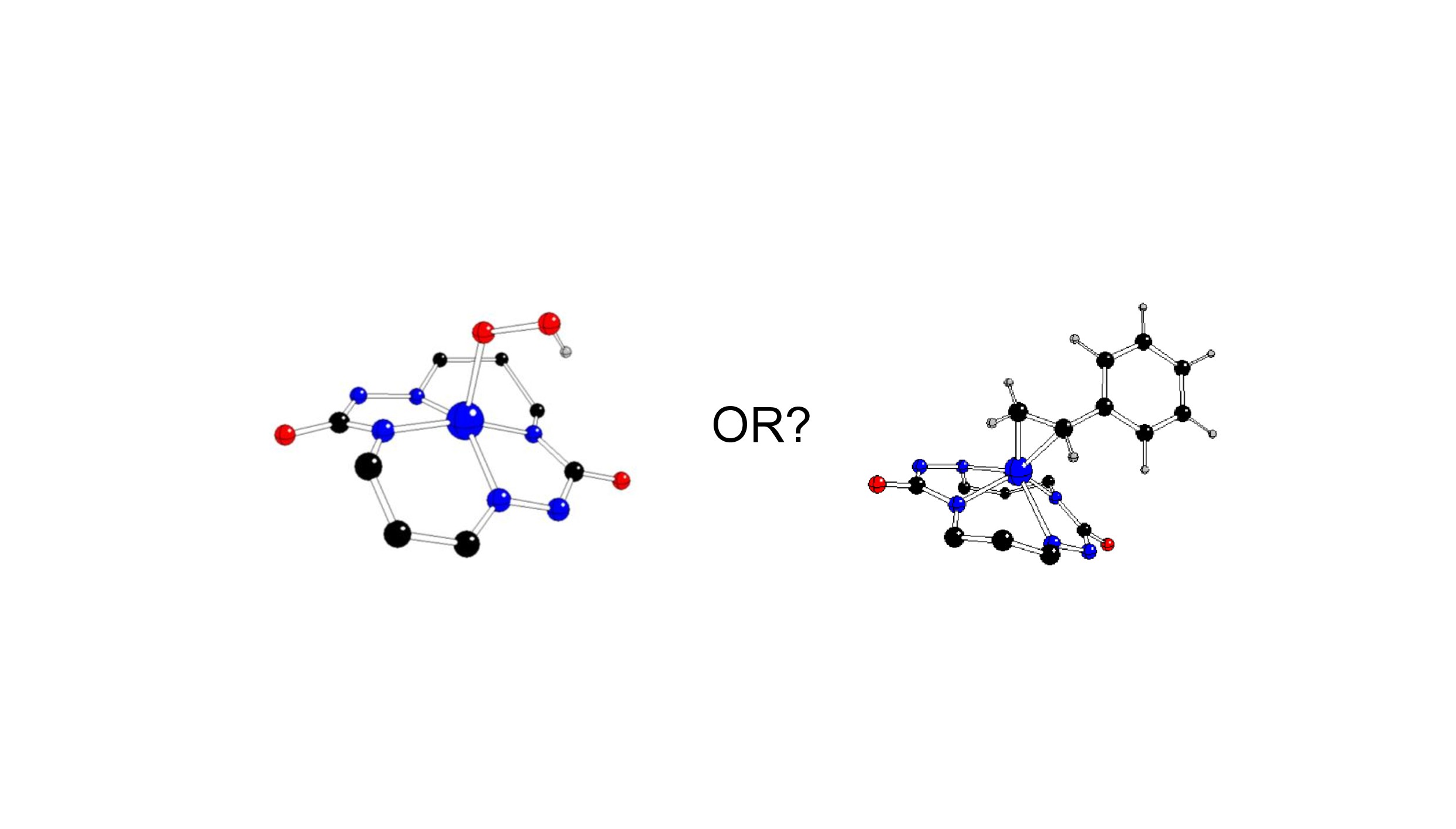

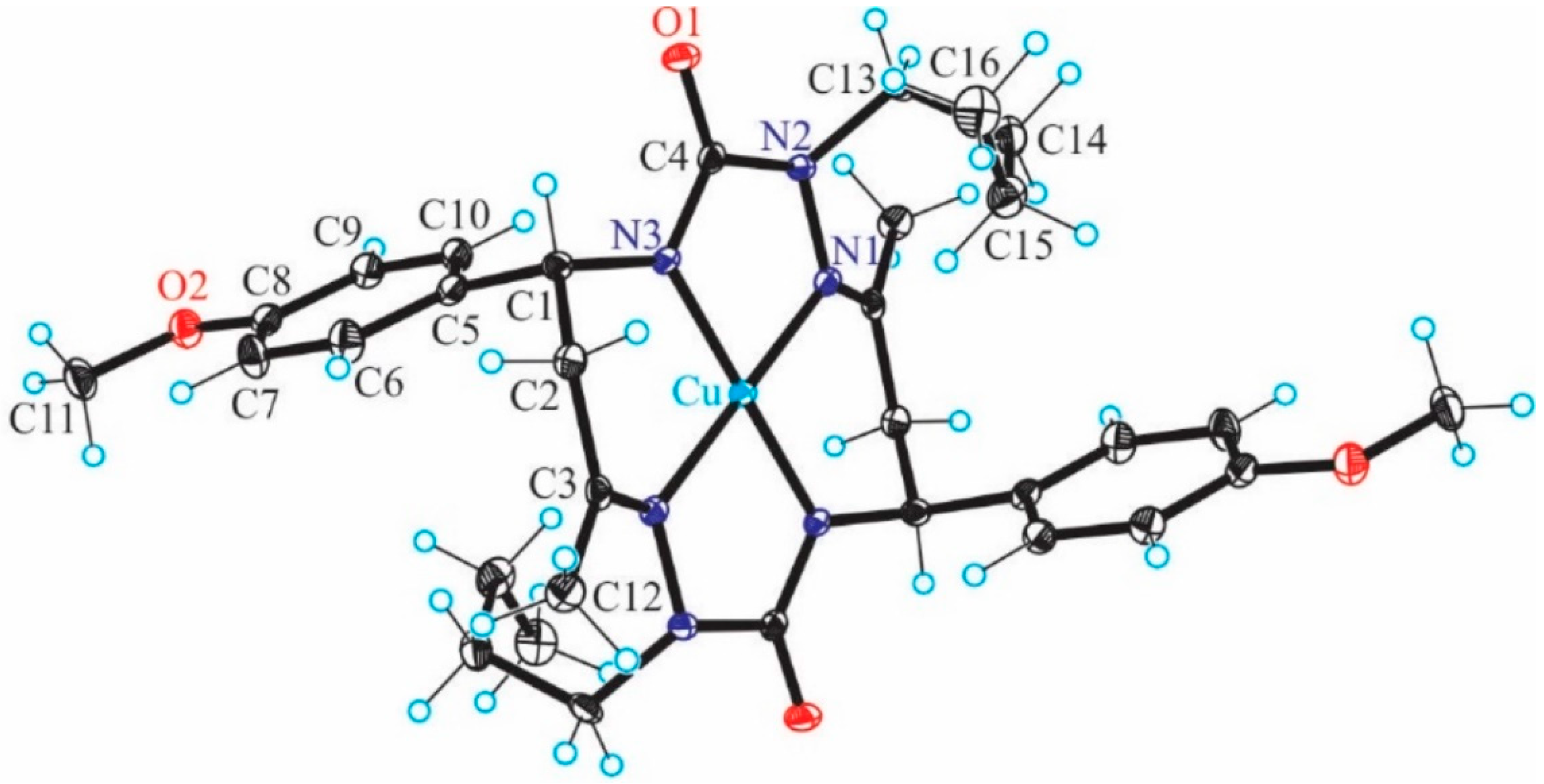

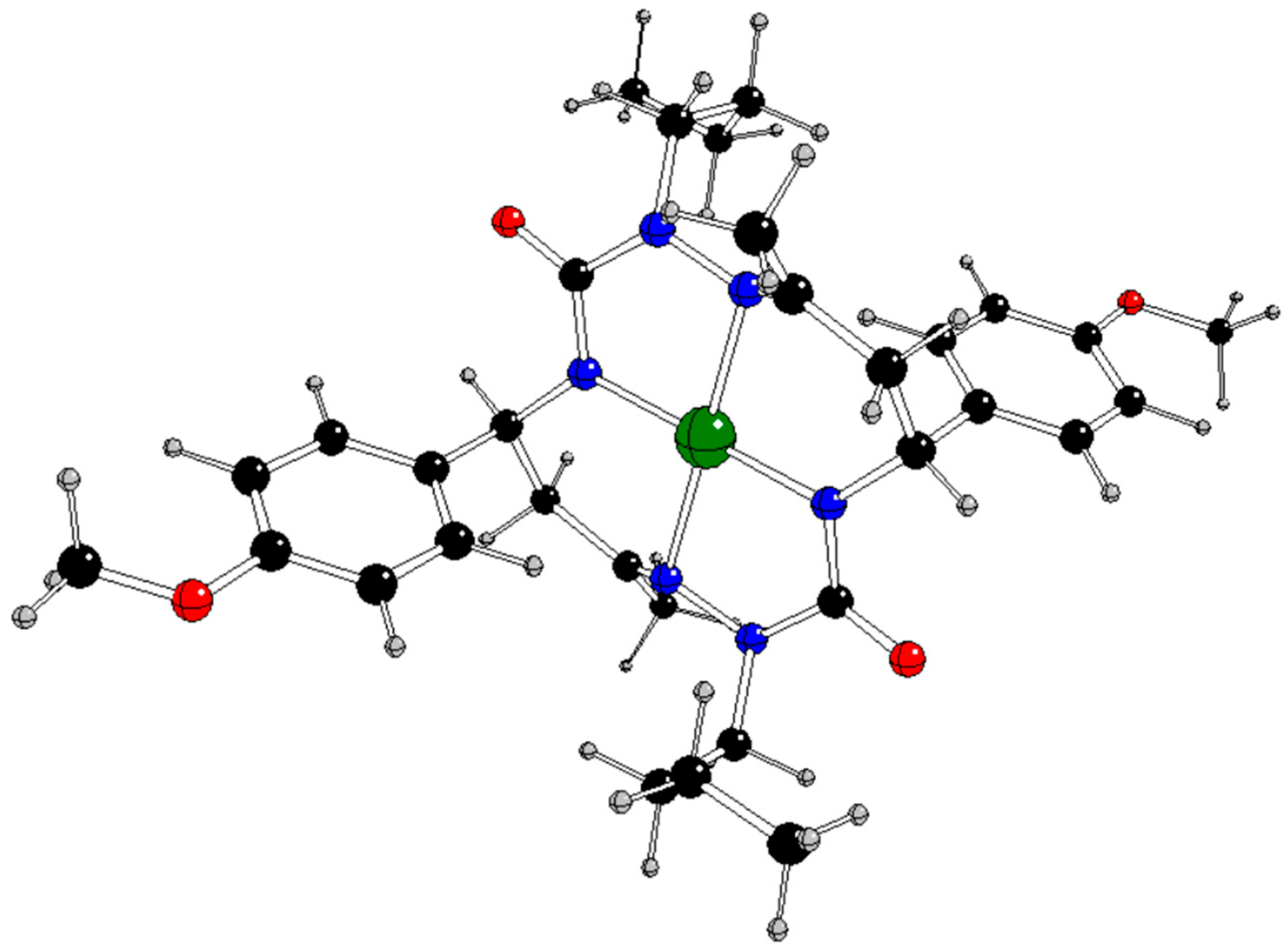

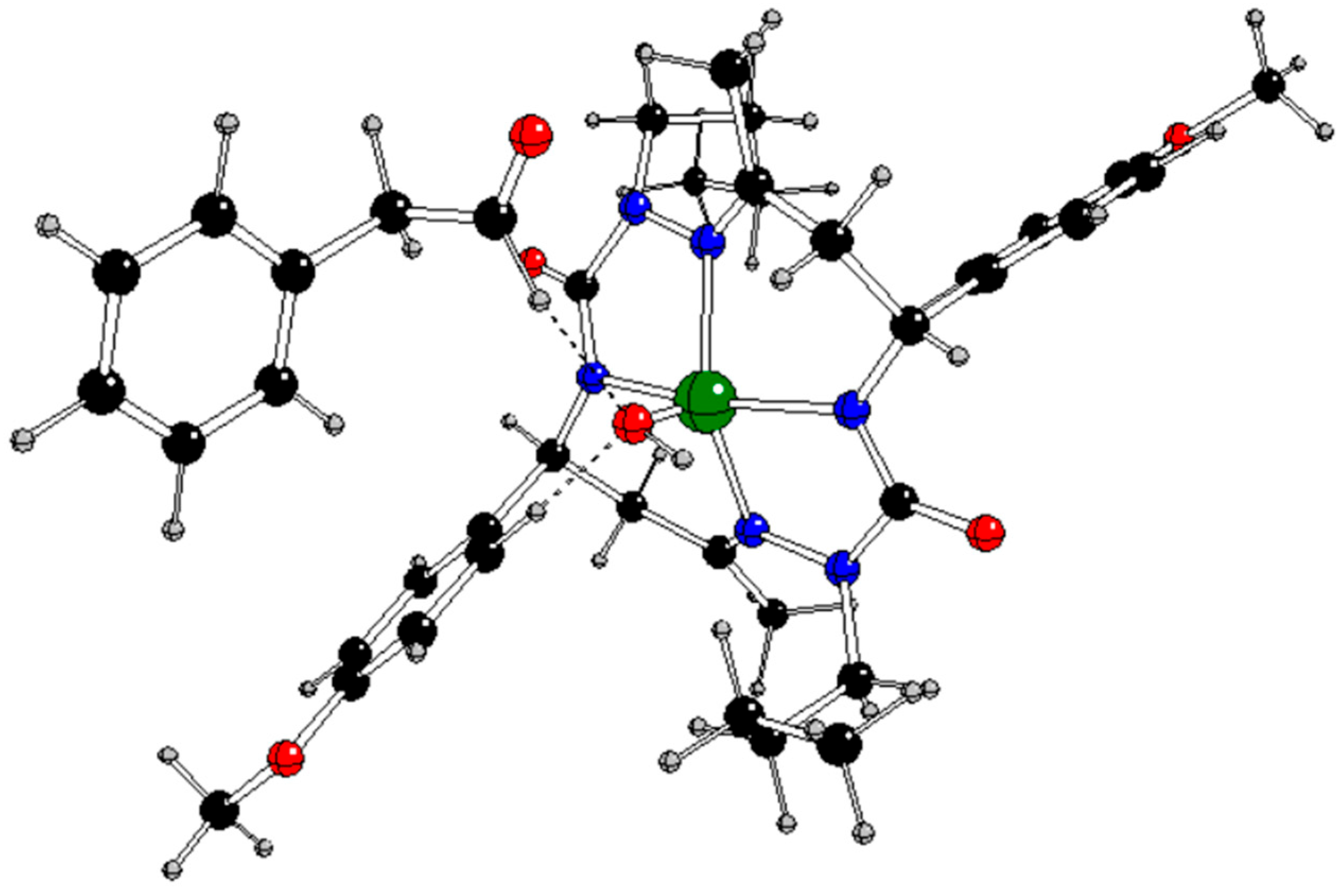

In our previous study [

13], the CuL complex (

Figure 1) with

trans-2,9-dibutyl-7,14-dimethyl-5,12-di(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,2,4,8,9,11-hexaazacyclotetradeca-7,14-diene-3,10-dione (H

2L), a 14-membered bis-semicarbazide hexaazamacrocycle (see

Figure S1 in Supplementary Information), was synthesized and characterized by analytical and spectroscopic techniques (IR, UV−vis,

1H and

13C NMR, ESI mass spectrometry, single-crystal X-ray diffraction, and spectroelectrochemistry). This complex selectively catalyzes the microwave-assisted oxidation of neat styrene to benzaldehyde using hydrogen peroxide (30% aqueous solution) as the oxidizing agent, under low microwave irradiation (25 W) and in the absence of any added solvent. Under optimized conditions (40 min of irradiation at 80 °C), the catalytic system provided benzaldehyde in a yield of up to 81% (turnover frequency up to 2.4 × 10

3 h 1) as the only product. The CuL catalyst can be very simply separated by cooling to room temperature.

In [

13] we proposed a free radical mechanism for the catalytic oxidation of styrene. It should be initiated by the Cu-assisted formation of the hydroxyl or hydroperoxyl radicals.

Now we plan to investigate possible mechanisms of styrene oxidation by hydrogen peroxide under CuL catalysis by quantum-chemical treatment. In this part of our study we will investigate structure, energy, and electron structure of relevant intermediates within three reaction pathways.

- i)

Reaction pathway A is a simple reaction of neutral styrene Ph-CH=CH2 with hydroperoxyl (O-OH)q .

- ii)

Reaction pathway B starts with the formation of a [CuL(OOH)]q complex followed by styrene addition.

- iii)

Reaction pathway C starts with the formation of the π-complex [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q and subsequent addition of hydroperoxyl.

All intermediates will be studied in various charge q and spin states to account for the noninnocent character of the ligand L2- and possible Cu(II)/Cu(I) equilibria. The obtained results should enable one to propose a realistic reaction pathway which will be studied in more detail in the next parts of this study.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Reaction Pathway A

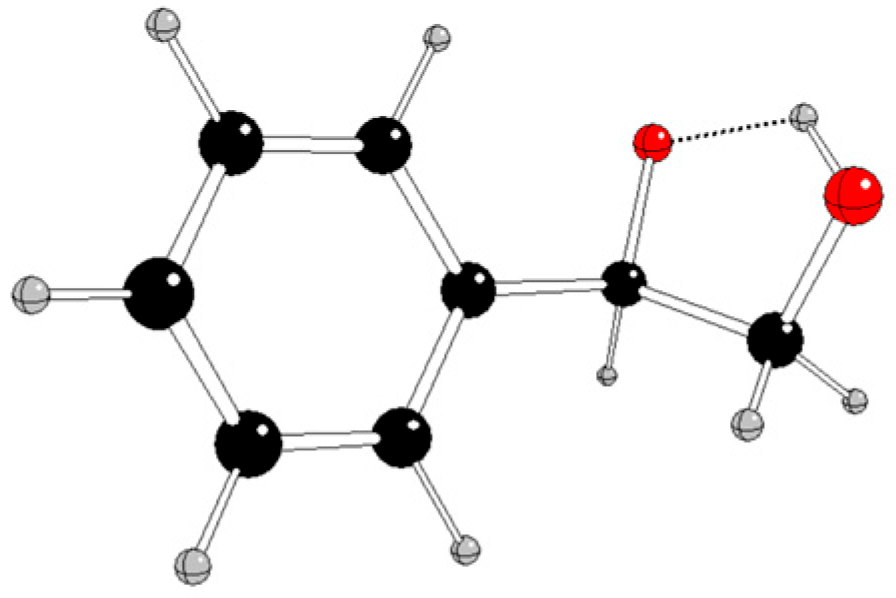

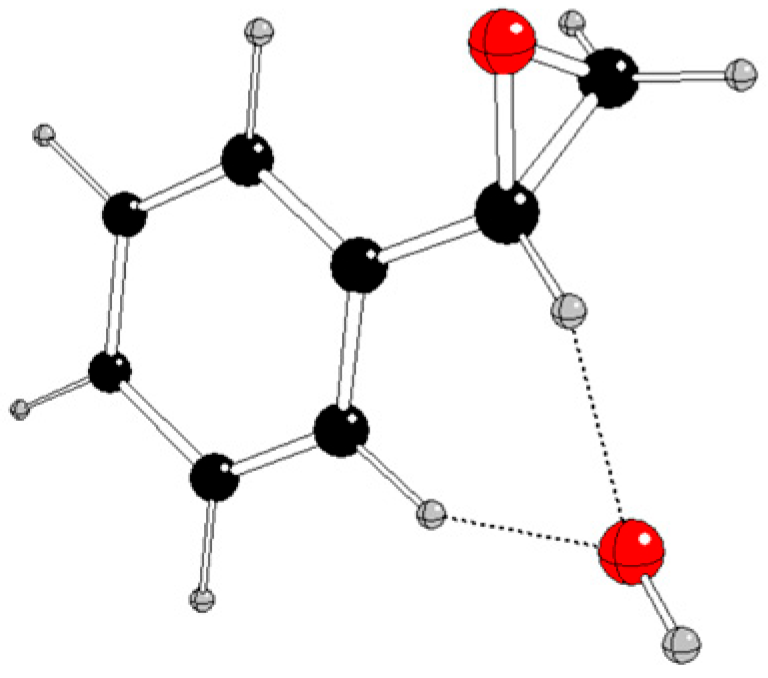

Selected energy and structure parameters of DFT optimized styrene, hydroperoxyl, and their reaction products in various charge and spin states are presented in

Tables 1 and S1 – S3 of Supplementary Information; their pictures are in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure S2 – S4 of Supplementary Information. The addition of the O – O

H bond

\ /

O

(C – black, O – red, H – gray).

Table 1.

Relative DFT energies, ΔEDFT, and Gibbs energies at 298 K, ΔG298, of the compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms. The energy values are related to the most stable systems (in bold) of the same composition.

Table 1.

Relative DFT energies, ΔEDFT, and Gibbs energies at 298 K, ΔG298, of the compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms. The energy values are related to the most stable systems (in bold) of the same composition.

| |

q |

Ms

|

ΔEDFT [kJ/mol] |

ΔG298 [kJ/mol] |

| Reaction path A |

|

|

|

|

| (OOH)q

|

0 |

2 |

94.99 |

97.20 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

67.03 |

53.90 |

| [Ph-CH(O)-CH2OH]q

|

0 |

2 |

251.65 |

252.31 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

321.52 |

307.97 |

[Ph - CH – CH2(OH)]q

\ /

O |

0 |

2 |

379.46 |

365.86 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

139.13 |

128.78 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

277.67 |

245.69 |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

| [CuL]q

|

0 |

2 |

127.26 |

148.50 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

90.95 |

97.98 |

| |

+1 |

1 |

748.24 |

776.49 |

| |

+1 |

3 |

778.22 |

799.62 |

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

224.48 |

232.30 |

| |

0 |

3 |

224.43 |

226.92 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

322.18 |

341.47 |

| |

0 |

3 |

323.41 |

333.39 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

37.81 |

20.01 |

| |

0 |

2 |

85.46 |

74.80 |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

184.97 |

182.87 |

| |

0 |

3 |

197.46 |

188.30 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Table 2.

Natural charges of Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

Table 2.

Natural charges of Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cα

|

Cβ

|

O |

OH

|

HO

|

| Reaction path A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (OOH)q

|

0 |

2 |

- |

- |

-0.145 |

-0.305 |

0.450 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

- |

- |

-0.767 |

-0.630 |

0.396 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

- |

- |

-0.511 |

-0.890 |

0.401 |

| Ph-CH=CH2

|

0 |

1 |

-0.191 |

-0.346 |

- |

- |

- |

| [Ph-CH(O)-CH2OH]q

|

0 |

2 |

0.052 |

0.012 |

-0.350 |

-0.691 |

0.565 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.106 |

-0.036 |

-0.945 |

-0.795 |

0.477 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

-0.025 |

-0.345 |

-0.360 |

-0.763 |

0.388 |

Ph - CH – CH2(OH)]q

\ /

O |

0 |

2 |

0.090 |

-0.044 |

-0.586 |

-0.434 |

0.416 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.042 |

-0.056 |

-0.587 |

-1.319 |

0.390 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

-0.025 |

-0.345 |

-0.763 |

-0.360 |

0.388 |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

- |

- |

-0.167 |

-0.317 |

0.484 |

| |

0 |

3 |

- |

- |

-0.167 |

-0.317 |

0.484 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

- |

- |

-0.614 |

-0.514 |

0.437 |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

-0.488 |

0.446 |

-0.566 |

-0.925 |

0.433 |

| |

0 |

3 |

-0.488 |

0.448 |

-0.561 |

-0.856 |

0.437 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

-0.491 |

0.436 |

-0.584 |

-1.188 |

0.424 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

-0.277 |

-0.472 |

- |

- |

- |

| |

-1 |

3 |

-0.240 |

-0.452 |

- |

- |

- |

| |

0 |

2 |

-0.192 |

-0.356 |

- |

- |

- |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.019 |

-0.251 |

-0.327 |

-0.452 |

0.461 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.012 |

-0.228 |

-0.319 |

-0.452 |

0.457 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.081 |

-0.785 |

-0.347 |

-0.454 |

0.440 |

Table 3.

Natural spin populations at Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

Table 3.

Natural spin populations at Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cα

|

Cβ

|

O |

OH

|

HO

|

| Reaction path A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (OOH)q

|

0 |

2 |

- |

- |

0.742 |

0.268 |

-0.010 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

- |

- |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

- |

- |

1.479 |

0.535 |

-0.014 |

| Ph-CH=CH2

|

0 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| [Ph-CH(O)-CH2OH]q

|

0 |

2 |

-0.029 |

0.116 |

0.820 |

0.033 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.050 |

0.346 |

0.862 |

0.032 |

0.074 |

[Ph - CH – CH2(OH)]q

\ /

O |

0 |

2 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.001 |

1.021 |

-0.023 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.568 |

-0.025 |

0.211 |

0.967 |

-0.018 |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

- |

- |

0.701 |

0.310 |

-0.008 |

| |

0 |

3 |

- |

- |

0.702 |

0.309 |

-0.008 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

- |

- |

0.097 |

0.007 |

0.001 |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

-0.002 |

-0.004 |

-0.005 |

-0.343 |

0.008 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.002 |

0.004 |

0.005 |

0.435 |

-0.011 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.035 |

-0.001 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

- |

- |

- |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.042 |

0.174 |

- |

- |

- |

| |

0 |

2 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

- |

- |

- |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.035 |

-0.998 |

-0.021 |

-0.006 |

0.000 |

| |

0 |

3 |

-0.029 |

0.982 |

0.065 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

-0.001 |

0.254 |

0.022 |

-0.001 |

0.000 |

Our results indicate that the most probable non-radical styrene oxidation in singlet spin state

Ph-CH=CH2 + (OOH)- → [Ph-CH(O)-CH2OH]- (1)

is highly exotermic (Gibbs reaction energy at normal condition Δ

rG

298 = -307.84 kJ/mol, compare

Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

Table 4.

Overlap weighted bond orders between Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

Table 4.

Overlap weighted bond orders between Cα, Cβ, O, OH and HO atoms in (O-OH-HO) and (Ph-CαH=CβH2) units with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms.

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cα-Cβ

|

Cα-O |

Cα-OH

|

Cβ-O |

Cβ-OH

|

O-OH

|

| Reaction path A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (OOH)q

|

0 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.679 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.417 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.090 |

| Ph-CH=CH2

|

0 |

1 |

1.380 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| [Ph-CH(O)-CH2OH]q

|

0 |

2 |

0.756 |

0.930 |

-0.026 |

0.010 |

0.823 |

-0.006 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.800 |

0.944 |

-0.023 |

-0.020 |

0.787 |

-0.022 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.935 |

0.834 |

-0.015 |

-0.048 |

0.699 |

0.010 |

[Ph - CH – CH2(OH)]q

\ /

O |

0 |

2 |

0.817 |

0.674 |

0.001 |

0.669 |

0.001 |

-0.010 |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.814 |

0.656 |

-0.020 |

0.685 |

-0.001 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.902 |

0.026 |

0.001 |

0.877 |

-0.002 |

-0.011 |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.720 |

| |

0 |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.719 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

0.505 |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.868 |

-0.027 |

0.000 |

1.292 |

-0.012 |

0.001 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.869 |

-0.026 |

0.000 |

1.294 |

-0.007 |

0.001 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.855 |

-0.027 |

0.001 |

1.282 |

-0.017 |

0.001 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

1.279 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

-1 |

3 |

1.279 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

0 |

2 |

1.379 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.949 |

0.722 |

-0.025 |

-0.025 |

0.000 |

0.530 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.958 |

0.690 |

-0.024 |

-0.019 |

-0.001 |

0.529 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.975 |

0.668 |

-0.027 |

-0.043 |

-0.005 |

0.524 |

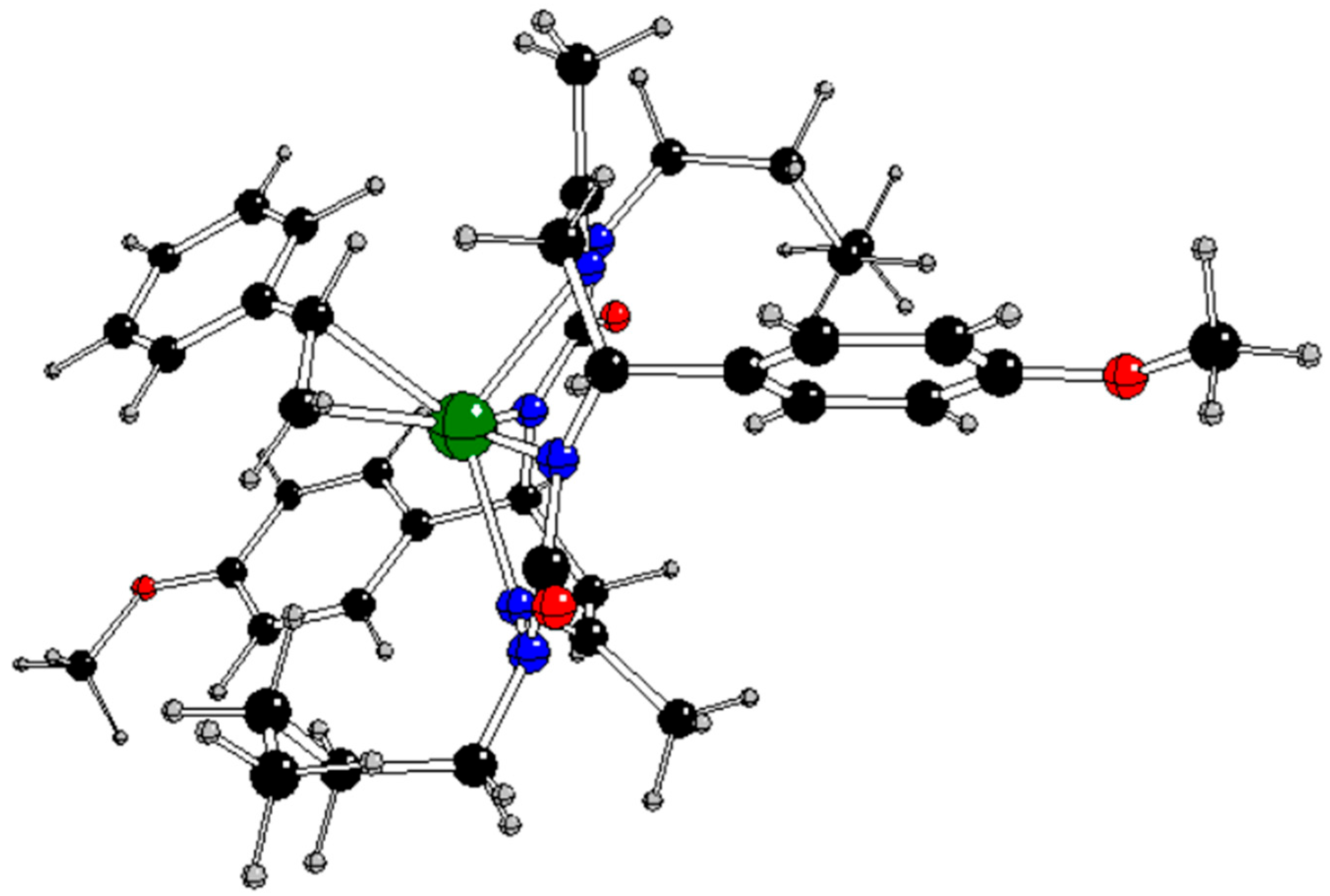

2.2. Reaction Pathway B

We optimized the geometry of [CuL]

q starting from its X-ray structure [

13] and subsequently with added hydroperoxyl (starting from the Cu – O distance of ca 2.2 Å) in various charge and spin states (the spin multiplicity is denoted as the left superscript where necessary). After geometry optimization, the original square-planar [CuL]

q complex changed its coordination to square-pyramidal only in the case of anionic doublet

2[CuL(OOH)]

- (

Tables S2 and S3 in Supplementary Information,

Figures 4 - 5 and S5 – S6 in Supplementary Information) while its neutral analogues contain the neutral hydroperoxyl radical (O-O

H-H

O)

0 (see atomic charges in

Table 2 and spin populations in

Table 3) attached by hydrogen bonding H

O…N3 (N3 has the highest negative charge and spin population among nitrogen atoms, see

Table 5 and

Table 6) without any Cu-O bond (see

Table 7,

Figure S6 and

Tables S2 – S3 in Supplementary Information). The anionic complexes

1[CuL]

- and

2[CuL(OOH)]

- are more stable than their neutral analogues (

Tables 1 and S1 in Supplementary Information). It can be deduced that they are related by the exothermic reaction

1[CuL]- + 2(OOH)0 → 2[CuL(OOH)]- (2)

as indicated by the reaction Gibbs energy under normal conditions Δ

rG

298 = -56.37 kJ/mol (

Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

Table 5.

Natural charges of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 for atom notation).

Table 5.

Natural charges of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 for atom notation).

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cu |

N1 |

N3 |

N2 |

| H2L |

0 |

1 |

- |

-0.357(2×) |

-0.680(2×) |

-0.383(2×) |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL]q

|

0 |

2 |

0.927 |

-0.339(2×) |

-0.787(2×) |

-0.363(2×) |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.603 |

-0.356(2×) |

-0.784(2×) |

-0.404(2×) |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.853 |

-0.334

-0.504 |

-0.748

-0.781 |

-0.373

-0.366 |

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

0.925 |

-0.348(2×) |

-0.859

-0.793 |

-0.350

-0.355 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.925 |

-0.348(2×) |

-0.859

-0.793 |

-0.350

-0.355 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.903 |

-0.315

-0.332 |

-0.777

-0.750 |

-0.369(2×) |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.923 |

-0.296

-0.303 |

-0.651

-0.677 |

-0.350

-0.347 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.955 |

-0.295

-0.307 |

-0.670

-0.722 |

-0.337

-0.348 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.956 |

-0.312

-0.317 |

-0.751

-0.743 |

-0.376

-0.356 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

0.670 |

-0.326

-0.270 |

-0.785

-0.782 |

-0.411

-0.356 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.885 |

-0.377

-0.396 |

-0.774

-0.781 |

-0.372(2×) |

| |

0 |

2 |

0.928 |

-0.340

-0.342 |

-0.787

-0.783 |

-0.362(2×) |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.931 |

-0.340

-0.342 |

-0.787

-0.784 |

-0.363

-0.363 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.926 |

-0.341

-0.341 |

-0.787

-0.780 |

-0.362

-0.363 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.848 |

-0.310(2×) |

-0.778

-0.759 |

-0.390

-0.351 |

Table 6.

Natural spin populations of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 for atom notation).

Table 6.

Natural spin populations of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 for atom notation).

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cu |

N1 |

N3 |

N2 |

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL]q

|

0 |

2 |

0.526 |

0.115(2×) |

0.111(2×) |

0.006(2×) |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.590 |

0.090

0.345 |

0.098

0.115 |

0.001

0.006 |

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

-0.532 |

-0.110(2×) |

-0.111

-0.116 |

-0.011

-0.006 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.525 |

0.110(2×) |

0.110

0.116 |

0.011

0.006 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.575 |

0.054

0.047 |

0.106(2×) |

0.002

0.004 |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.197 |

0.104(2×) |

-0.061

0.022 |

0.008

0.003 |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.673 |

0.138(2×) |

0.296

0.186 |

0.050

0.008 |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.610 |

0.059

0.065 |

0.109

0.106 |

0.000

0.002 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.571 |

0.153

0.166 |

0.111

0.108 |

0.000

0.002 |

| |

0 |

2 |

0.526 |

0.115(2×) |

0.112

0.110 |

0.006(2×) |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.527 |

0.115(2×) |

0.112

0.109 |

0.007(2×) |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.527 |

0.115(2×) |

0.111(2×) |

0.007(2×) |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.507 |

0.000

0.023 |

0.083

0.087 |

-0.001

0.002 |

The spin population in

2[CuL(OOH)]

- is located mainly at Cu, unlike the spinless

1[CuL]

-. Consequently, the spin transfer from neutral hydroperoxyl radical to central Cu atom can be concluded in reaction (2) which is connected with weakening of the O-O

H bond (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Subsequent addition of neutral styrene to the hydroperoxyl group in

2[CuL(OOH)]

- similarly to reaction pathway A (due to sterical reasons C

β must be close to O and C

α close to OH) causes hydrogen and oxygen transfers resulting to

2{[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH

2-CHO)}

- where Ph-CH

2-CH=O is only weakly bonded to [CuL(OH)]

- (

Figure 6,

Table 7 and S2 – S3 in Supplementary Information). Here, the O atom originally bonded to Cu is moved to C

β simultaneously with H transfer from C

β to C

α and Cu is bonded to O

H of hydroperoxyl. It is interesting that if we remove one electron, analogous neutral complexes are obtained (

Figure S7,

Tables S2 – S3 in Supplementary Information) with significantly higher energies (

Table 1 and S1 in supplementary Information). Consequently, the C

α-C

β bonds are weakened and the double C

β=O bonds are formed (

Figure 4). The strengths of Cu-O bonds are comparable with those of Cu-N1/N3 (

Figure 7) and the Cu coordination is square-pyramidal (unlike

Table 7.

Overlap weighted bond orders of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 and

Table 2 for atom notation).

Table 7.

Overlap weighted bond orders of the relevant atoms in some compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities M

s (see

Figure 1 and

Table 2 for atom notation).

| |

q |

Ms

|

Cu-N1 |

Cu-N3 |

Cu-O/OH

|

Cu-Cα/β

|

| Reaction path B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL]q

|

0 |

2 |

0.260(2×) |

0.339(2×) |

- |

- |

| |

-1 |

1 |

0.188(2×) |

0.298(2×) |

- |

- |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.272

0.357 |

0.338

0.346 |

- |

- |

| [CuL(OOH)]q

|

0 |

1 |

0.232

0.230 |

0.311

0.305 |

0.069

0.015 |

- |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.232

0.230 |

0.310

0.305 |

0.070

0.015 |

- |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.238

0.215 |

0.305

0.313 |

0.302

0.023 |

- |

| {[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.293

0.297 |

0.384

0.391 |

0.000

0.333 |

0.000(2×) |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.287

0.295 |

0.362

0.386 |

0.000

0.333 |

0.000(2×) |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.241

0.233 |

0.308

0.310 |

-0.001

0.309 |

0.004

0.009 |

| Reaction path C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

|

-1 |

1 |

0.172

0.132 |

0.220

0.240 |

- |

0.195

0.240 |

| |

-1 |

3 |

0.287

0.294 |

0.332(2×)

|

- |

-0.001

0.007 |

| |

0 |

2 |

0.259(2×) |

0.338(2×) |

- |

0.001(2×) |

| {CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}q

|

0 |

1 |

0.258(2×)

|

0.337

0.333 |

0.000(2×) |

0.000(2×) |

| |

0 |

3 |

0.258

0.260 |

0.337

0.339 |

0.000(2×) |

0.000(2×) |

| |

-1 |

2 |

0.161

0.178 |

0.277

0.262 |

0.010

0.003 |

0.052

0.324 |

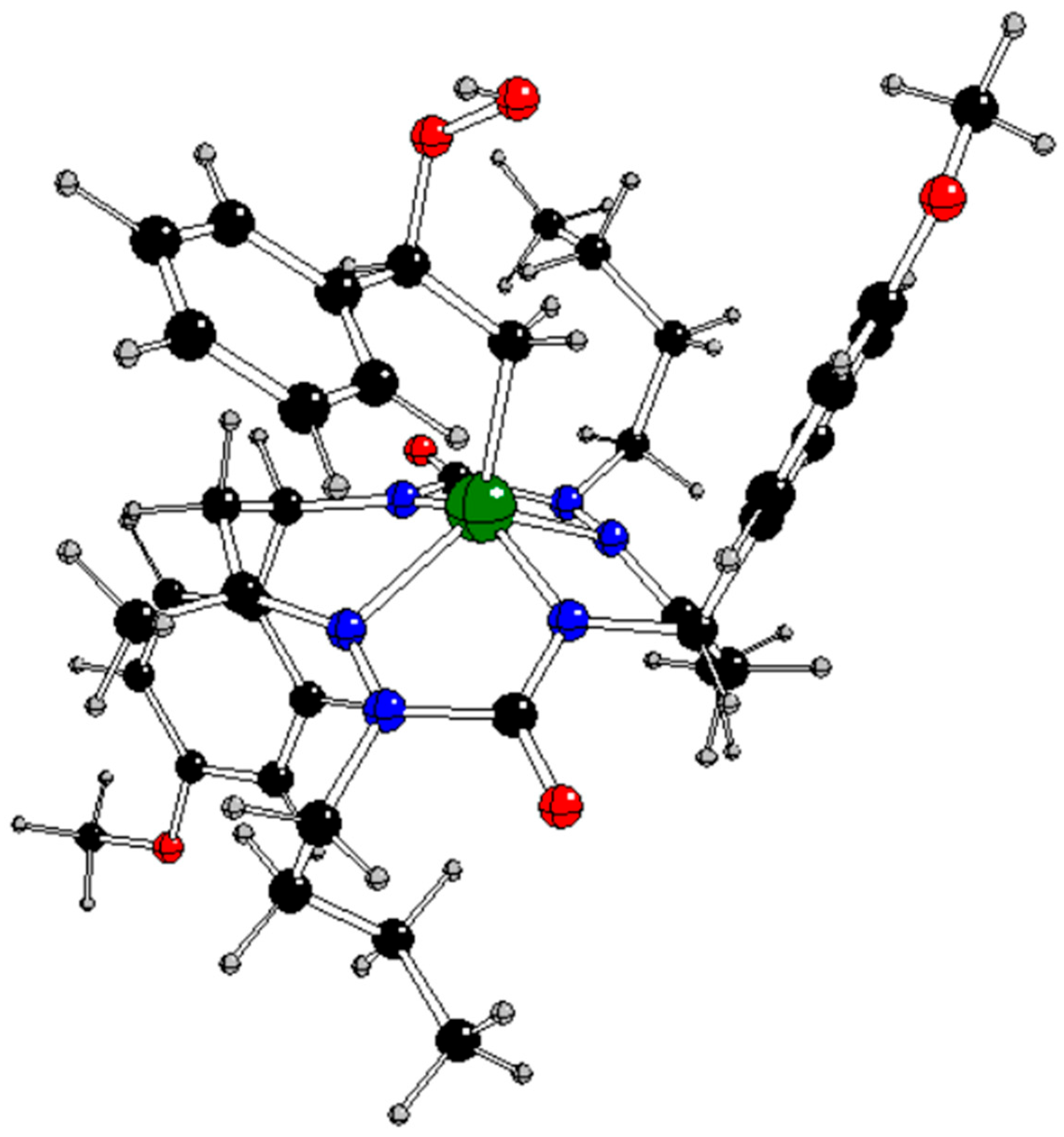

The most probable styrene oxidation step can be described by the exothermic reaction

2[CuL(OOH)]- + Ph-CH=CH2 → 2{[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH2-CHO)}- (3)

as indicated by the reaction Gibbs energy under normal conditions Δ

rG

298 =-266.67 kJ/mol (

Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

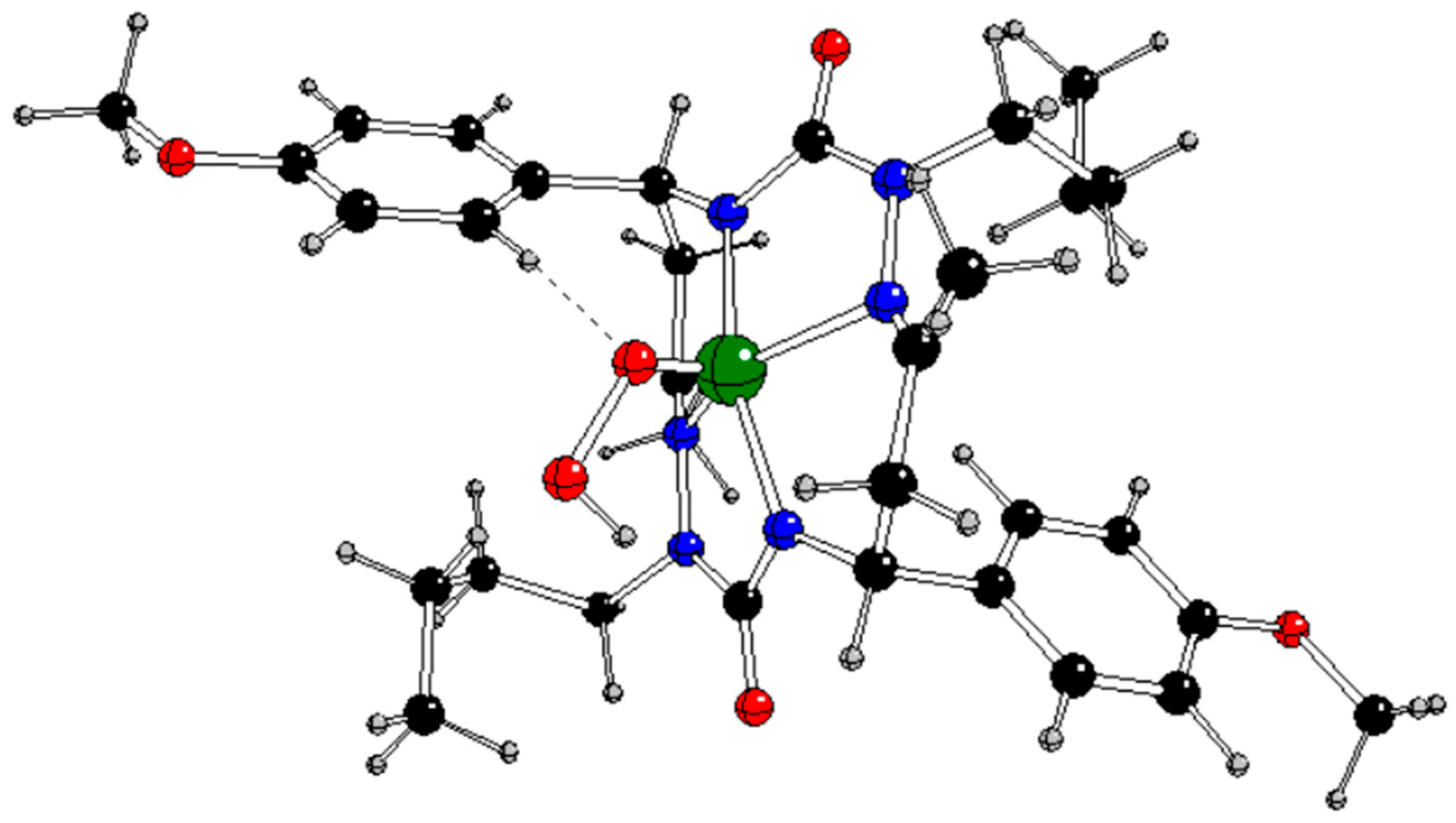

2.3. Reaction Pathway C

We optimized the structures of [CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]q

starting from the optimized structures of [CuL]q with added

neutral styrene in the form of a π-complex with Cu-Cα/β distances

of ca 2.4 Å. Only the optimized structure of 1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]-

preserved the original form of a π-complex where

the Cu- Cα/β bond lengths are comparable with the Cu-N1/N3 ones

and the square-planar Cu coordination lost its planarity (Figure 7, Tables

S2 – S3 in supplementary Information). Its 1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]0

and 3[CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]- analogues with

separated square-planar [CuL]q and neutral Ph-CH=CH2

components are energetically higher (Table 1,

S1 – S3, and Figure S8 in Supplementary

Information).

Figure 7.

DFT optimized structure of [CuL(Ph-CαH=CβH2)]- in singlet spin state (Cu – green, C – black, N – blue, O – red, H – gray).

Figure 7.

DFT optimized structure of [CuL(Ph-CαH=CβH2)]- in singlet spin state (Cu – green, C – black, N – blue, O – red, H – gray).

The lower charge and absence of spin at Cu in

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- indicates the formal oxidation state Cu(I) unlike the Cu(II) one in [CuL]

q,

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

0 and

3[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- (

Table 5Tables –

Table 6). The Cu-N1/N3 bonds in

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- are weaker than in [CuL]

q and comparable with the Cu-C

α/β ones (

Table 7). The C

α=C

β bond strength is equal to that of free styrene (

Table 4).

According to our results, the only stable π-complex can be obtained by the non-radical endothermic reaction

1[CuL]- + Ph-CH=CH2 → 1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]- (4)

as indicated by the reaction Gibbs energy under normal conditions Δ

rG

298 = +91.95 kJ/mol (

Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

The addition of the hydroperoxyl radical to

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- leads to

2{CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH

2]}

- (analogously to the reaction pathway A) with a split Cu-C

α bond and hydroperoxyl bonding to the C

α site (

Figure 8,

Tables S2-S3 in Supplementary Information). Subsequently, the spin density is moved from hydroperoxyl to Cu with a higher positive charge corresponding to the real oxidation state instead of Cu(I) in

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- (

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 5 and

Table 6). The Cu-N1/N3 bonds are weaker than the Cu-C

β one in

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- (

Table 7).

Figure 8.

DFT optimized structure of {CuL[Ph-CαH(O-OH-HO)-CβH2]}- in doublet spin state (Cu – green, C – black, N – blue, O – red, H – gray).

Figure 8.

DFT optimized structure of {CuL[Ph-CαH(O-OH-HO)-CβH2]}- in doublet spin state (Cu – green, C – black, N – blue, O – red, H – gray).

An electron removal from

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- should correspond to the formal oxidation state Cu(II) but it causes the Ph-CH(OOH)-CH

2 split from the [CuL]

0 unit (

Tables S2-S3 and

Figure S9 in Supplementary Information) with higher energies (

Tables 1 and S1 in Supplementary Information). Based on charges and spin populations (

Tables 2, 3, 5 and 6), the real Cu(II) oxidation state is preserved in neutral [CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

0 complexes and the spin density is moved from hydroperoxyl to N1 and N3 atoms.

Our results show that the most advantageous hydroperoxyl addition to the above mentioned π-complex can be described by the endothermic reaction

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH2)]- + 2(OOH)0 → 2{CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH2]}- (5)

as indicated by the reaction Gibbs energy under normal conditions Δ

rG

298 = -35.92 kJ/mol (

Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

3. Method

Geometry optimization of the systems under study was performed using B3LYP hybrid functional [

14] and 6-311+G* basis sets from the Gaussian library [

15]. The optimized structures were tested on the absence of imaginary vibrations using vibrational analysis. Singlet spin states in Cu complexes were treated using an unrestricted formalism and their energies related to triplet spin states were corrected as follows (‘broken symmetry’ treatment, BS) [

16].

(6)

E

S, E

T and E

BS are singlet, triplet, and ‘broken symmetry’ (unrestricted singlet) energies, respectively. <S

2>

T and <S

2>

BS are triplet and ‘broken symmetry’ values of spin squares, respectively. Atomic charges, spin populations, and overlap weighted bond orders were evaluated in terms of natural population analysis [

17,

18]. All quantum-chemical calculations were performed using Gaussian16 software [

15]. The MOLDRAW software was used for geometry manipulation and visualization purposes [

20].

4. Conclusions

Using quantum-chemical treatment, relevant intermediates in various charge and spin states of three reaction pathways of styrene oxidation by hydroperoxyl were investigated. The reaction pathway A without any catalyst probably proceeds by non-radical mechanism when neutral styrene is attacked by a hydroperoxyl anion and

1[Ph-CH(O)-CH

2OH]

- is formed (

Figure 2). The alternative formation of epoxide (

Figure 3) is energetically less advantageous.

The alternative reaction pathways B and C are based on the [CuL]

q catalyst (

Figure 1), most probably its anionic form in the singlet spin state corresponding to the formal oxidation state Cu(I). Within the reaction pathway B the neutral hydroperoxyl radical is bonded to Cu to form

2[CuL(OOH)]

- (

Figure 4) which is unstable in other charge and spin states. The spin density is moved to Cu, which corresponds to the real oxidation state of Cu(II). Subsequent addition of neutral styrene results in

2{[CuL(OH)](Ph-CH

2-CHO)}

- formation after significant O and H atoms rearrangements which contains only weakly bonded

2[CuL(OH)]

- and Ph-CH

2-CH=O units. This reaction pathway seems to be realistic, but in future studies we must solve the Cu-OH split (probably by reaction with hydroperoxyl as in [

4,

5]) and the formation of benzaldehyde (by interaction with hydroperoxyl [

4] or with

2[CuL(OH)

]- [

3,

7]).

The reaction pathway C starts with the initial non-radical formation of the π-complex

1[CuL(Ph-CH=CH

2)]

- (

Figure 7) with the oxidation state of Cu(I) according to Eq. (4) but this reaction is problematic because of its endothermic character. However, its analogues in other charge and spin states do not allow for such a π-complex formation. Subsequent addition of a hydroperoxyl radical leads to

2{CuL[Ph-CH(OOH)-CH

2]}

- (

Figure 8) with Cu-C

β bonding. Its oxidation leads to Ph-CH(OOH)-CH

2 separation.

Our study explains why reaction pathway B of the catalytic oxidation of styrene by hydroperoxylating a bis-semicarbazide hexaazamacrocyclic Cu complex is preferred. Our future studies will provide additional details of its reaction mechanism, including solvent effects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: DFT energies, EDFT, and Gibbs energies at 298 K, G298, of the compounds under study with charges q, spin multiplicities Ms, and spin squares <S2>; Table S2: Selected bond lengths (in Å) between relevant atoms in the compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms; Table S3: Selected bond angles (in degrees) in the compounds under study with charges q and spin multiplicities Ms; Figure S1: X-ray structure of H2L with atom-labelling scheme and thermal ellipsoids drawn at 20% probability level; Figures S2 – S9: DFT optimized structures of the possible reaction intermediates in various charge q and spin states Ms.

Funding

Slovak Grant Agency VEGA (contract No. 1/0175/23) is acknowledged for financial support.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the HPC center at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, which is a part of the Slovak Infrastructure of High-Performance Computing (SIVVP Project, ITMS code 26230120002, funded by the European Region Development Funds), for computing facilities. .

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrade, M.A.; Martins, L.M.D.R.S. Selective Styrene Oxidation to Benzaldehyde over Recently Developed Heterogeneous Catalysts. Molecules 2021, 26, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, J.A. ; P. M. Henry, P.M. The Mechanism of the Wacker Reaction: A Tale of Two Hydroxypalladations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9038–9049. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou., Sh.; Chen, X.; Qia, Ch. Quantum chemical modeling of the epoxidation with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by Mn(III): Mechanistic insight. Chem. Phys. Let. 2010, 488, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashanizadegan, M.; Alavijeh, R.K.; Anafcheh, M. Facile synthesis of Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes of 2-hydroxybenzophenone: An efficient catalyst for oxidation of olefins and DFT study. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1146, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashanizadegan, M.; Ashari, H.A.; Sarkheil, M.; Anafcheh, M.; Jahangiry, S. New Cu(II), Co(II) and Ni(II) azo-Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, characterization, catalytic oxidation of alkenes and DFT study. Polyhedron 2021, 200, 115148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashanizadegan, M.; Habibi, N.; Mirzazadeh, H.; Ghiasi, M. Immobilized magnetic copper hydrazine complexes for oxidation of styrene to benzaldehyde by tert-butylhydroxyperoxide: an experimental and theoretical approach. React. Kinet., Mechan. Catal. 2022, 135, 3223–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.A.; Sarazen, M.L. Mechanistic Impacts of Metal Site and Solvent Identities for Alkene Oxidation over Carboxylate Fe and Cr Metal−Organic Frameworks. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 14476–14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kang, J.; Gao, W.; Bi, M.; Yang, D.; Ji, R.; Meng, Q.; Ma, C. A DFT and kinetic study: Is it possible to prepare epoxides without catalysts using the in-situ generated peroxy radicals or peroxides by one-step method? J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 44, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhafez, N.; Ehlers, A.W; de Bruin, B.; Gramage-Doria, R. Markovnikov-Selective Cobalt-Catalyzed Wacker-Type Oxidation of Styrenes into Ketones under Ambient Conditions Enabled by Hydrogen Bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202316825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vala, G.; Jadeja, R.N.; Patel, A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D. Development of novel heterogeneous cobalt acylpyrazolone catalyst: Synthesis, characterization and selective oxidation of styrene to benzaldehyde. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2024, 563, 121925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmara, Z.; Necas, M.; Karimi, P. Oxidation of styrene by Mn (II)-pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate complex: Synthesis, X-ray structure and DFT studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1330, 141440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeh, K.; Louroubi, A.; Abdallah, N.; Fkhar, L. , Aflak, N.; Bahsis, L.; Hasnaoui, A.; Ali, M.A.; El Firdoussi, L. Elaboration and characterization of Zn1−xCoxFe2O4 spinel ferrites magnetic material: application as heterogeneous catalysts in styrene oxidation. React. Kinet., Mechan. Catal. 2025, 138, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, A.; Fesenko, A.; Yankov, A.; Stepanenko, I.; Darvasiova, D.; Breza, M.; Rapta, P.; Martins, L.M.D.R.S.; Pombeiro, A.J.L.; Shutalev, A.; Arion, V.B. Nickel(II), Copper(II) and Palladium(II) Complexes with Bis-Semicarbazide Hexaazamacrocycles: Redox-Noninnocent Behavior and Catalytic Activity in Oxidation and C−C Coupling Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 10650–10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B. G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H. P.; Ortiz, J. V.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Williams-Young, D.; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M. J.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E. N.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T. A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A. P.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian 16, Rev. C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Malrieu, J.-P.; Trinquier, G. A Recipe for Geometry Optimization of Diradicalar Singlet States from Broken-Symmetry Calculations, J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 8226–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J. P.; Weinhold, F. Natural Hybrid Orbitals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 7211–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J. E.; Weinhold, F. Analysis of the Geometry of the Hydroxymethyl Radical by the “Different Hybrids for Different Spins” Natural Bond Orbital Procedure. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1988, 169, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugliengo, P. MOLDRAW: A Program to Display and Manipulate Molecular and Crystal Structures, University Torino, Torino, 2012. Available online: https://moldraw.software.informer.com (accessed on 9 September 2019).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).