Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

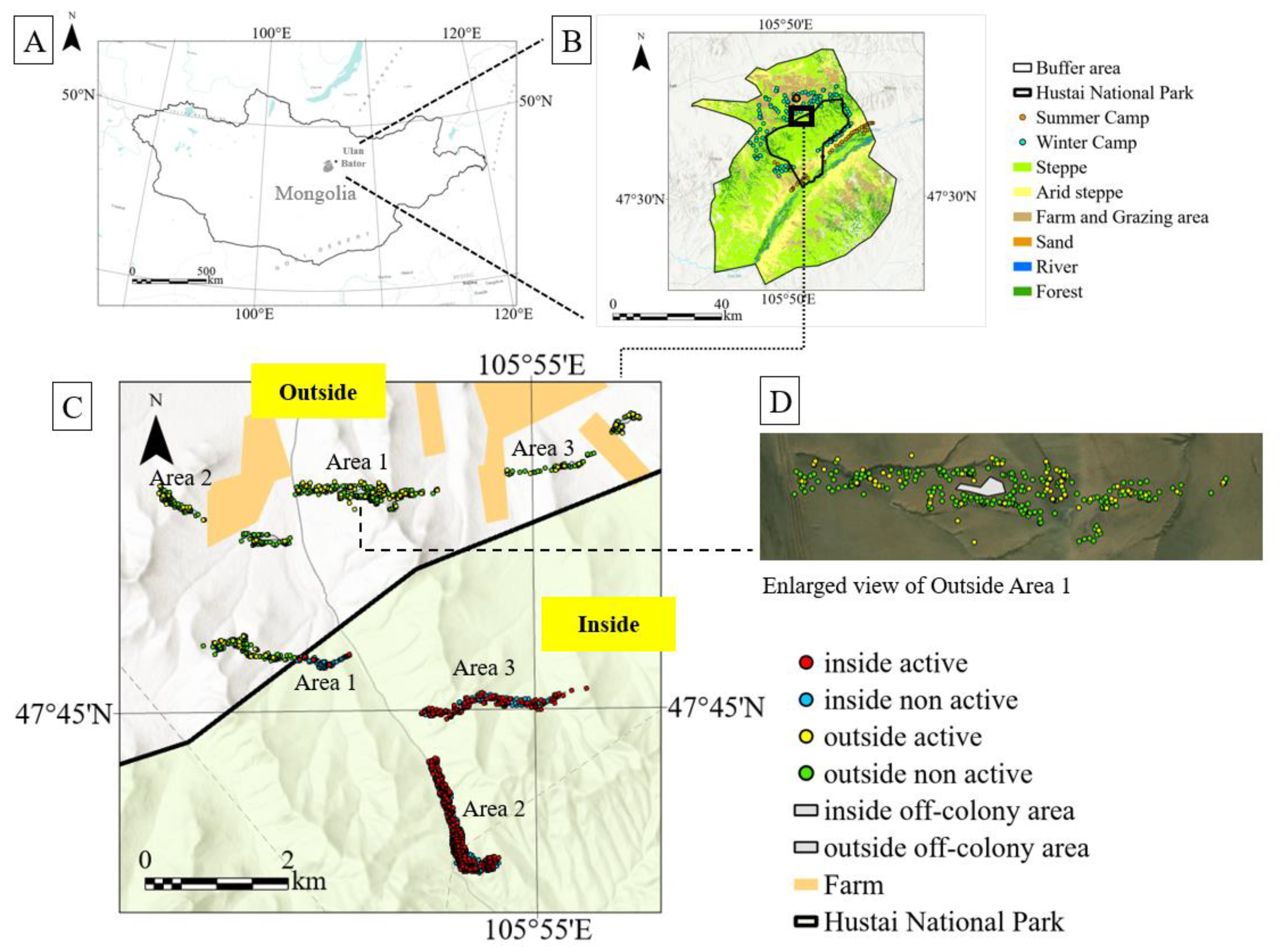

2.1. Survey Area

2.2. Data Used

2.3. Analysis of Habitat Structure

2.4. Vegetation Survey

2.5. Vegetation Index Extraction and Analysis

2.6. Analysis of the Relationship Between Burrow Activity and NDVI

3. Results

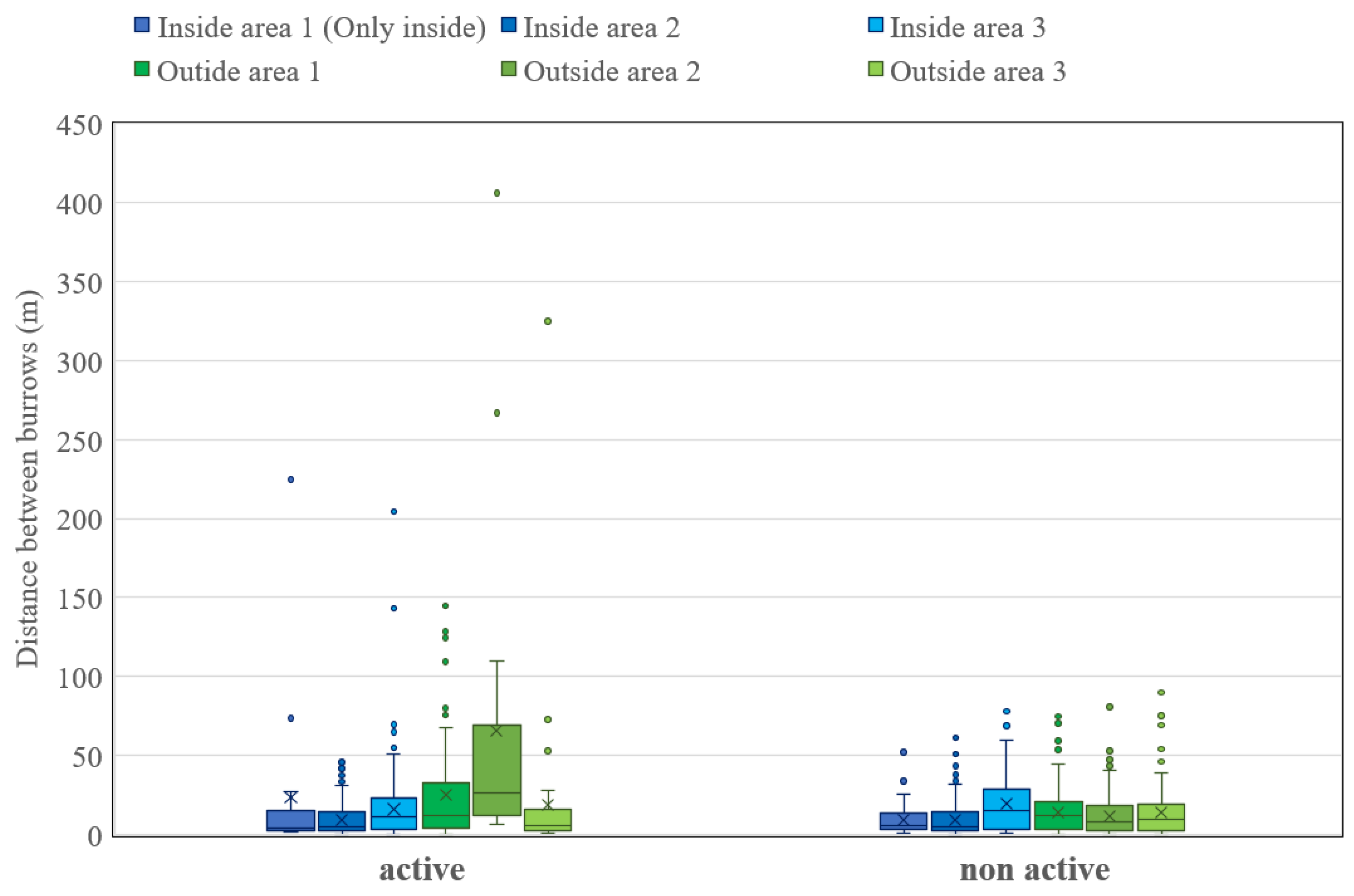

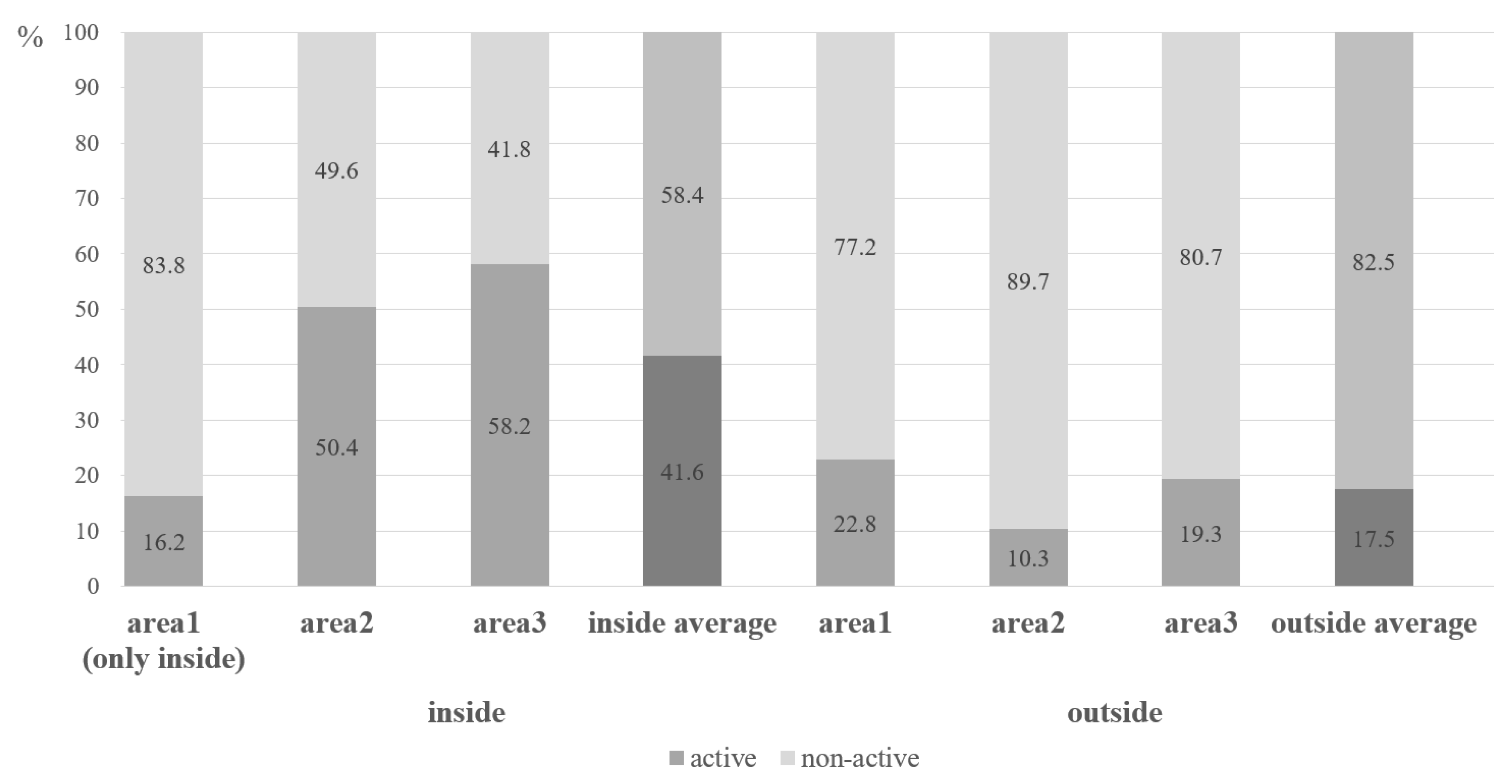

3.1. Habitat Structure and Activity Patterns of Marmots

3.2.1. Effects of the Protected Area and Marmot Burrows on Plant Community Structure (2023–2024)

Results for 2023

Results for 2024

| Year | Factor | Df | Sum of Squares | R² | F | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Area (inside/outside) | 1 | 0.6576 | 0.2001 | 4.3645 | **0.001** | *** |

| Status (active burrow/off-colony area) | 1 | 0.1502 | 0.0457 | 0.9969 | 0.417 | ||

| Area × Status | 1 | 0.0678 | 0.0206 | 0.45 | 0.870 | ||

| 2024 | Area | 1 | 0.2775 | 0.2161 | 2.6054 | *0.027* | * |

| Status | 1 | 0.3844 | 0.2993 | 3.6084 | **0.004** | ** | |

| Area × Status | 1 | 0.1961 | 0.1527 | 1.841 | *0.081* | . (marginal) |

| 2023 | Inside | outside | ||||||

| active burrow | off-colony area | active burrow | off-colony area | |||||

| Artemisia adamsii | 13.6% | Artemisia adamsii | 22.8% | Stipa krylovii | 17.0% | Heteropappus hispidus | 19.0% | |

| Heteropappus hispidus | 9.8% | Carex duriuscula | 14.2% | Artemisia adamsii | 16.0% | Allium anisopodium | 12.0% | |

| Stipa krylovii | 9.2% | Leymus chinensis | 13.4% | Leymus chinensis | 9.2% | Stipa krylovii | 11.0% | |

- PERMANOVA = Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance.

- NMDS = Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling; a stress value < 0.1 indicates a reliable 2D representation.

- Significant effects (p < 0.05) are indicated with asterisks: p < 0.05 = *.p < 0.01 = **.p < 0.001 = ***.p < 0.1 = . (marginal)

- Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was used as the distance metric.

- Values in bold or asterisk-marked cells indicate statistically significant or marginally significant results.

3.2.2. Comparison of Vegetation Height

- For Artemisia frigida, vegetation height on active burrows inside the park (mean: 9.2 cm) was significantly lower than in off-colony areas (mean: 22.6 cm) (t = -6.04, p = 0.0004), indicating potential suppression of vegetation cover or growth on burrows.

- For Artemisia adamsii, vegetation height on active burrows outside the park (mean: 20.8 cm) was significantly higher than in off-colony areas (mean: 9.8 cm) (t = 4.18, p = 0.0041). However, due to a limited sample size, statistical testing could not be conducted for this species inside the park.

- For Leymus chinensis, no significant differences in vegetation height were observed in either area (inside: p = 0.191; outside: NA), suggesting that the impact of burrows may be limited for this species.

| Species | Area | Active Burrow Mean (n) | Off-Colony Area Mean (n) | Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stipa krylovii | Inside | 59.3 (6) | 57.8 (6) | 0.214 | 0.836 |

| Stipa krylovii | Outside | 55.5 (6) | 35.2 (11) | 3.59 | 0.0027 |

| Leymus chinensis | Inside | 23.0 (6) | 28.0 (5) | -1.45 | 0.191 |

| Leymus chinensis | Outside | – (5) | – (0) | – | – |

| Artemisia frigida | Inside | 9.17 (6) | 22.6 (5) | -6.04 | <0.001 |

| Artemisia adamsii | Inside | – (0) | – (6) | – | – |

| Artemisia adamsii | Outside | 20.8 (6) | 9.83 (6) | 4.18 | 0.0041 |

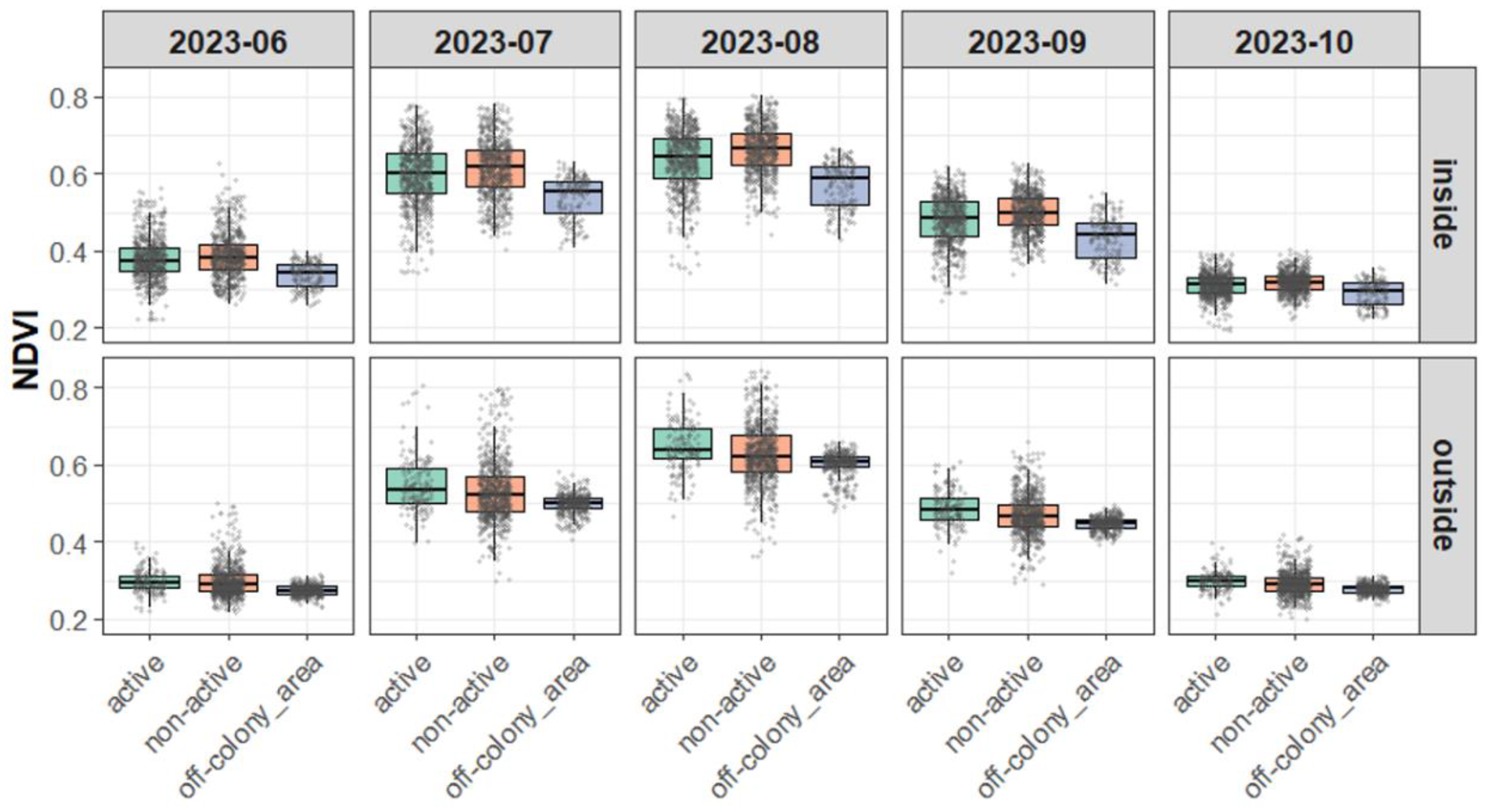

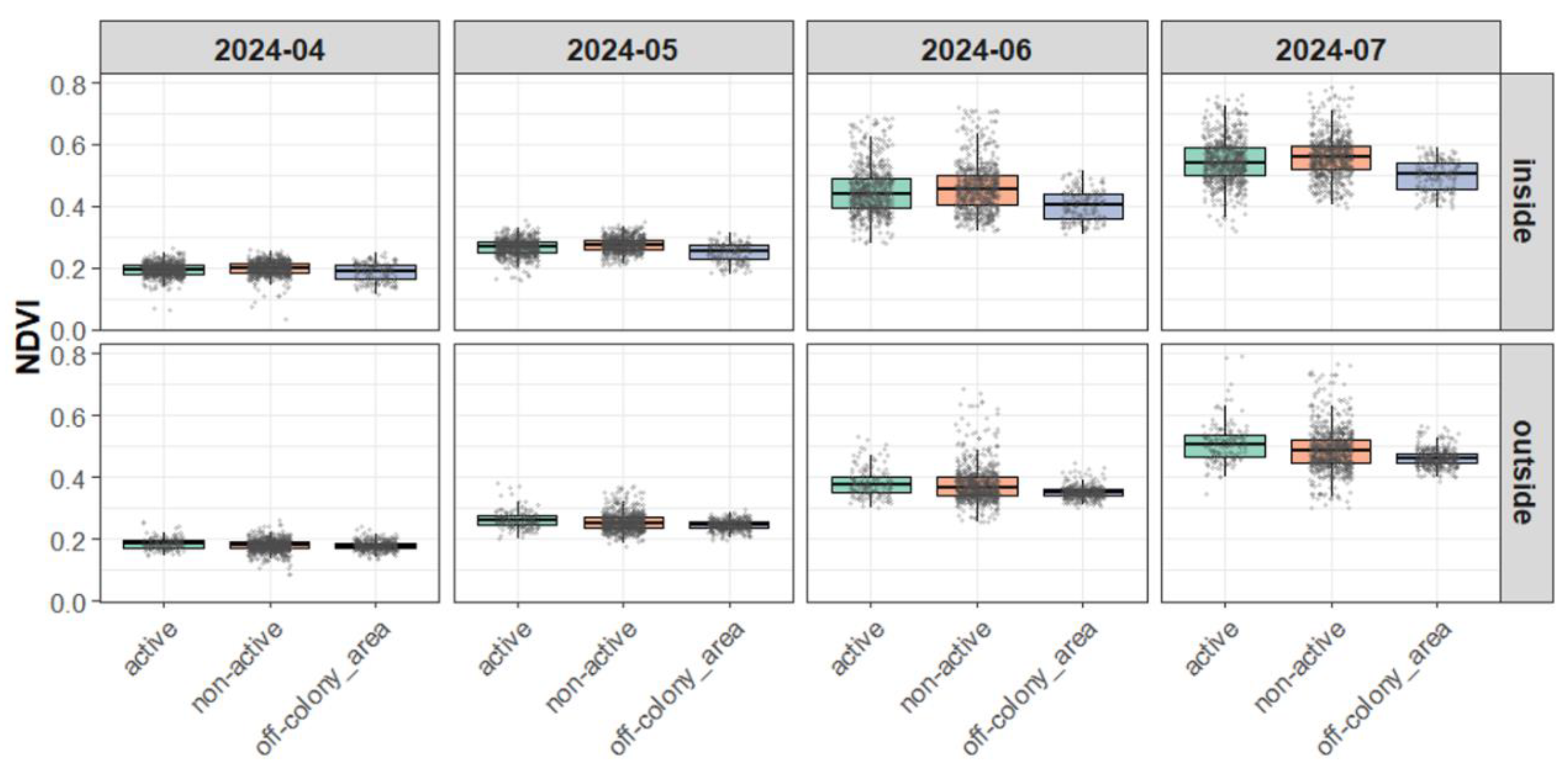

3.3. Results of Burrow Activity and Vegetation Index (NDVI)

3.3.1. NDVI Distribution Characteristics and Model Fit

| Predictor | Estimate (2023) | Std. Error | z-Value | Estimate (2024) | Std. Error | z-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | –0.1198 | 0.0322 | –3.72 | –0.6123 | 0.0321 | –19.10 | ||

| area (outside) | –0.0532 | 0.0457 | –1.16 | –0.0641 | 0.0467 | –1.37 | ||

| burrow type (non-active) | 0.0827 | 0.0137 | 6.05*** | 0.0575 | 0.0162 | 3.56** | ||

| burrow type (off-colony area) | –0.1385 | 0.0635 | –2.18* | –0.0728 | 0.0626 | –1.16 | ||

| area × burrow type (non-active) | –0.1344 | 0.0257 | –5.23*** | –0.0950 | 0.0306 | –3.11** | ||

| area × burrow type (off-colony area) | –0.0063 | 0.0887 | –0.07 | –0.0278 | 0.0876 | –0.32 | ||

| Statistic | 2023 | 2024 | ||||||

| AIC (interaction model) | –16,285.7 | –13,792.7 | ||||||

| AIC (additive model) | –16,261.2 | –13,734.1 | ||||||

| ΔAIC (interaction – additive) | 24.6 | 58.6 | ||||||

3.3.2. Variance in NDVI Across Burrow Types

3.3.3. Visual Supplement

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Competing interest

Appendix A

| Year | Month | Area | Comparison | F Value | Pr(>F) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Jun | Inside | active vs non-active | 1.6856 | 0.1944 | n.s. |

| active vs off-colony | 19.41 | 1.19E-05 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 25.757 | 4.77E-07 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 3.8999 | 0.04859 | * | ||

| active vs off-colony | 106.06 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 115.81 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2023 | Jul | Inside | active vs non-active | 2.6713 | 0.1024 | n.s. |

| active vs off-colony | 25.562 | 5.27E-07 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 19.292 | 1.26E-05 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 1.0398 | 0.3081 | n.s. | ||

| active vs off-colony | 133.46 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 177.51 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2023 | Aug | Inside | active vs non-active | 23.42 | 1.45E-06 | *** |

| active vs off-colony | 7.2054 | 0.007412 | ** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 0.0665 | 0.7966 | n.s. | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 3.0339 | 0.08188 | . | ||

| active vs off-colony | 96.862 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 182.43 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2023 | Sep | Inside | active vs non-active | 23.398 | 1.47E-06 | *** |

| active vs off-colony | 0.4516 | 0.5018 | n.s. | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 7.1883 | 0.007481 | ** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 0.5464 | 0.46 | n.s. | ||

| active vs off-colony | 181.59 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 193.47 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2023 | Oct | Inside | active vs non-active | 9.032 | 0.002702 | ** |

| active vs off-colony | 5.0711 | 0.02459 | * | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 20.634 | 6.37E-06 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 2.7936 | 0.09499 | . | ||

| active vs off-colony | 70.386 | 4.12E-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 118.84 | < 2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2024 | Apr | Inside | active vs non-active | 0.3341 | 0.5633 | n.s. |

| active vs off-colony | 39.726 | 4.72E-10 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 30.622 | 4.19E-08 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 0.3207 | 0.5713 | n.s. | ||

| active vs off-colony | 4.7067 | 0.03047 | * | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 13.22 | 0.000289 | *** | |||

| 2024 | May | Inside | active vs non-active | 4.8423 | 0.02794 | * |

| active vs off-colony | 8.6904 | 0.003288 | ** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 24.639 | 8.37E-07 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 0.444 | 0.5054 | n.s. | ||

| active vs off-colony | 35.685 | 4.16E-09 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 69.166 | 2.57E-16 | *** | |||

| 2024 | Jun | Inside | active vs non-active | 0.0069 | 0.9336 | n.s. |

| active vs off-colony | 17.613 | 2.99E-05 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 18.283 | 2.12E-05 | *** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 2.5934 | 0.1077 | n.s. | ||

| active vs off-colony | 107.89 | <2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 119.88 | <2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| 2024 | Jul | Inside | active vs non-active | 2.4171 | 0.1203 | n.s. |

| active vs off-colony | 13.105 | 0.000312 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 7.4029 | 0.006646 | ** | |||

| Outside | active vs non-active | 2.7545 | 0.09733 | . | ||

| active vs off-colony | 73.145 | <2.2e-16 | *** | |||

| non-active vs off-colony | 142.14 | <2.2e-16 | *** |

References

- Reichman, O. J., & Seabloom, E. W. (2002). The role of pocket gophers as subterranean ecosystem engineers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 17(1), 44-49. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A. D., Detling, J. K., & Brown, J. H. (2012). Ecological roles and conservation challenges of social, burrowing, herbivorous mammals in the world’s grasslands. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(9), 477-486. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Dou, H., Wei, S., Fang, Y., Long, Z., Wang, J., ... & Jiang, G. (2021). A review of the engineering role of burrowing animals: Implication of Chinese Pangolin as an Ecosystem Engineer. Journal of Zoological Research, 3(3). [CrossRef]

- Whicker, A. D., & Detling, J. K. (1988). Ecological consequences of prairie dog disturbances. BioScience, 38(11), 778-785. [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. P., & Jones, C. G. (2006). The concept of organisms as ecosystem engineers ten years on: progress, limitations, and challenges. BioScience, 56(3), 203-209. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/202001805_The_Concept_of_Organisms_as_Ecosystem_Engineers_Ten_Years_On_Progress_Limitations_and_Challenges.

- Wesche, K., Nadrowski, K., & Retzer, V. (2007). Habitat engineering under dry conditions: the impact of pikas (Ochotona pallasi) on vegetation and site conditions in southern Mongolian steppes. Journal of Vegetation Science, 18(5), 665-674. [CrossRef]

- Prugh, L. R., & Brashares, J. S. (2012). Partitioning the effects of an ecosystem engineer: kangaroo rats control community structure via multiple pathways. Journal of Animal Ecology, 667-678. [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. O., Murdoch, J. D., Newman, D. P., & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2009). Vulpes corsac (Carnivora: Canidae). Mammalian Species, (832), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M. L., Bennett, D. E., & Holbrook, J. D. (2021). Burrow webs: Clawing the surface of interactions with burrows excavated by American badgers. Ecology and Evolution, 11(17), 11559-11568. [CrossRef]

- Gharajehdaghipour, T., Roth, J. D., Fafard, P. M., & Markham, J. H. (2016). Arctic foxes as ecosystem engineers: increased soil nutrients lead to increased plant productivity on fox dens. Scientific reports, 6(1), 24020. [CrossRef]

- Hagenah, N., & Bennett, N. C. (2013). Mole rats act as ecosystem engineers within a biodiversity hotspot, the C ape F ynbos. Journal of Zoology, 289(1), 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A. W., Apollonio, M., Krausman, P. R., & Rachlow, J. L. (2016). Pygmy rabbit burrows increase microhabitat heterogeneity in sagebrush-steppe ecosystems. Ecosphere, 7(6), e01334. [CrossRef]

- Valkó, O., Tölgyesi, C., Kelemen, A., Bátori, Z., Gallé, R., Rádai, Z., ... & Deák, B. (2021). Steppe Marmot (Marmota bobak) as ecosystem engineer in arid steppes. Journal of Arid Environments, 184, 104244. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A. W., Apollonio, M., Krausman, P. R., & Rachlow, J. L. (2016). Pygmy rabbit burrows increase microhabitat heterogeneity in sagebrush-steppe ecosystems. Ecosphere, 7(6), e01334. [CrossRef]

- Valkó, O., Tölgyesi, C., Kelemen, A., Bátori, Z., Gallé, R., Rádai, Z., ... & Deák, B. (2021). Steppe Marmot (Marmota bobak) as ecosystem engineer in arid steppes. Journal of Arid Environments, 184, 104244. [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. D., Munkhzul, T., Buyandelger, S., Reading, R. P., & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2009). The endangered Siberian marmot Marmota sibirica as a keystone species? Observations and implications of burrow use by corsac foxes Vulpes corsac in Mongolia. Oryx, 43(3), 431-434. [CrossRef]

- Buyandelger, S., & Otgonbayar, B. (2022). Mongolian marmot burrow influences an occupancy of Isabelline wheatear. Landscape and Ecological Engineering, 18(2), 239-245. [CrossRef]

- Becchina, R. A. (2020). Recovering Endangered Siberian Marmot (Marmota sibirica): Status and Distribution in a Steppe Region of Mongolia. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/331.

- Buyandelger, S., Baatargal, O., Bayartogtokh, B., & Reading, R. P. (2022). Ecosystem engineering influence of Mongolian marmots (Marmota sibirica) on small mammal communities in Mongolia. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 15(2), 172-179. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, V. V., Brandler, O. V., Badmaev, B. B., Zoje, D., & Adiya, Y. (2009). Factors that lead to a decline in numbers of Mongolian marmot populations. Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 21(3-4), 371-379. [CrossRef]

- Buyandelger, S., Enkhbayar, T., Otgonbayar, B., Zulbayar, M., & Bayartogtokh, B. (2021). Ecosystem engineering effects of Mongolian marmots (Marmota sibirica) on terrestrial arthropod communities. Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences, 19(1), 17-30. Retrieved from https://www.biotaxa.org/mjbs/article/view/66415.

- Townsend, S. E. (2009). Estimating Siberian marmot (Marmota sibirica) densities in the Eastern Steppe of Mongolia. Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 21(3-4), 325-338. [CrossRef]

- Fijn, N., & Terbish, B. (2021). The multiple faces of the marmot: associations with the plague, hunting, and cosmology in Mongolia. Human Ecology, 49(5), 539-549. [CrossRef]

- Thapaliya, K. (2008). Analysis of factors related to the distribution of red deer, Cervus elephus L., in Hustai National Park, Mongolia. ITC. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237632048_Analysis_of_factors_related_to_the_distribution_of_Red_deer_Cervus_elephus_L_in_Hustai_National_Park_Mongolia.

- Suzuki, K., Kamijo, T., Jamsran, U., & Tamura, K. (2013). Evaluation of the effect of protected area designation by comparing steppe vegetation inside and outside Hustai National Park, Mongolia. Journal of Vegetation Science, 30(2), 85–93. [In Japanese]. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, Y., Okuro, T., Buuveibaatar, B., Undarmaa, J., & Takeuchi, K. (2010). Clustered animal burrows yield higher spatial heterogeneity. Plant Ecology, 206, 211-224. [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. (2019). Mongolia: Overgrazing problem and its impact on grasslands. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2019/298/article-A002-en.xml.

- Shen, H., Dong, S., DiTommaso, A., Xiao, J., & Zhi, Y. (2021). N deposition may accelerate grassland degradation succession from grasses-and sedges-dominated into forbs-dominated in overgrazed alpine grassland systems on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecological Indicators, 129, 107898. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., & Sun, J. (2021). Impact of soil degradation on plant communities in an overgrazed Tibetan alpine meadow. Journal of Arid Environments, 193, 104586. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, Y., Ohkuro, T., Buuveibaatar, B., Undarmaa, J., & Takeuchi, K. (2010). Pollinators are attracted to mounds created by burrowing animals (marmots) in a Mongolian grassland. Journal of Arid Environments, 74(1), 159-163. [CrossRef]

- Ulziibaatar, M., & Matsui, K. (2021). Herders’ Perceptions about Rangeland Degradation and Herd Management: A Case among Traditional and Non-Traditional Herders in Khentii Province of Mongolia. Sustainability, 13(14), 7896. [CrossRef]

- Narmandakh, D., & Sakurai, T. (2022). Impact of Rangeland Degradation on Farm Performance and Household Welfare in the Case of Mongolia. Japanese Journal of Agricultural Economics, 24, 52-57. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, Y., Ohkuro, T., Bayarbaatar, B., & Takeuchi, K. (2009). Effects of disturbance by Siberian marmots (Marmota sibirica) on spatial heterogeneity of vegetation at multiple spatial scales. Grassland Science, 55(2), 89-95. [CrossRef]

- King, S. R., & Gurnell, J. (2005). Habitat use and spatial dynamics of takhi introduced to Hustai National Park, Mongolia. Biological Conservation, 124(2), 277-290. [CrossRef]

- Hustai National Park. (n.d.). Brief history of Hustai National Park establishment. Retrieved from https://www.hustai.mn/language/en.

- Rouse, J. W., Haas, R. H., Schell, J. A., & Deering, D. W. (1973). Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. Third ERTS Symposium, NASA SP-351 I, 309–317. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19740022614.

- Kizilgeci, F., Yildirim, M., Islam, M. S., Ratnasekera, D., Iqbal, M. A., & Sabagh, A. E. (2021). Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Chlorophyll Content for Precision Nitrogen Management in Durum Wheat Cultivars under Semi-Arid Conditions. Sustainability, 13(7), 3725. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M. E., Kristensen, K., van Benthem, K. J., Magnusson, A., Berg, C. W., Nielsen, A., Skaug, H. J., Mächler, M., & Bolker, B. M. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal, 9(2), 378–400. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2017/RJ-2017-066/index.html.

- Ballova, Z., Pekarik, L., Píš, V., & Šibík, J. (2019). How much do ecosystem engineers contribute to landscape evolution? A case study on Tatra marmots. Catena, 182, 104121. [CrossRef]

- Buuveibaatar, B., & Yoshihara, Y. (2012). Effects of food availability on time budget and home range of Siberian marmots in Mongolia. Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences, 10(1-2), 25-31. Retrieved from https://www.biotaxa.org/mjbs/article/view/26596.

- Yokohama, M., Shimada, S. & Sekiyama, A. (2011). Vegetation and forage preference of livestock in the Mongolian steppe. Bulletin of Tokyo University of the Arts, 56(1), 1-9. Retrieved from https://nodai.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/458 [In Japanese].

- Kawashima, K., Hoshino, B., Ganzorig, S., Sawamuki, M., Asakawa, M., & Batsaikhan, N. (2012). Distribution and expansion of Microtus brandti in overgrazed areas in Mongolia. Grassland Science, 59(3), 217-224. [In Japanese]. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., & Sun, J. (2021). Impact of soil degradation on plant communities in an overgrazed Tibetan alpine meadow. Journal of Arid Environments, 193, 104586. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Batelaan, O., Guan, H., Duan, L., Liu, T., Wang, Y., ... & Yang, B. (2024). Evaluation of the contributions of climate change and overgrazing to runoff in a typical grassland inland river basin. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 52, 101725. [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, C. J. (2015). Olympic marmot burrow densities and their effects on alpine soil properties. Physical Geography, 36(4), 293–307. [CrossRef]

- Miura, N., Ito, T. Y., Lhagvasuren, B., Enkhbileg, D., Tsunekawa, A., Takatsuki, S., ... & Mochizuki, K. (2004). Analysis of the seasonal migrations of Mongolian gazelle, using MODIS data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inform. Sci., 35, 418-422. Retrieved from https://www.readkong.com/page/analysis-of-the-seasonal-migrations-of-mongolian-gazelle-5744763.

- Ito, T. Y., Sakamoto, Y., Lhagvasuren, B., Kinugasa, T., & Shinoda, M. (2018). Winter habitat of Mongolian gazelles in areas of southern Mongolia under new railroad construction: an estimation of interannual changes in suitable habitats. Mammalian Biology, 93, 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Harmse, C. J., Gerber, H., & Van Niekerk, A. (2022). Evaluating several vegetation indices derived from Sentinel-2 imagery for quantifying localized overgrazing in a semi-arid region of South Africa. Remote Sensing, 14(7), 1720. [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, Y., Okuro, T., Buuveibaatar, B., Undarmaa, J., & Takeuchi, K. (2010). Complementary effects of disturbance by livestock and marmots on the spatial heterogeneity of vegetation and soil in a Mongolian steppe ecosystem. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment, 135(1-2), 155-159. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (n.d.). Mongolian grasslands and drylands: Overview of grazing lands and land use in Mongolia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/4/y8344e/y8344e0e.htm.

- WWF. (2021). The Parliament of Mongolia has approved 22 areas for national protected areas. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved from https://www.wwf.mg/en/?346744/The-Parliament-of-Mongolia-has-approved-22-areas-for-national-protected-areas.

- Yoshihara, Y. (2013). Impact of overgrazing on ecosystems and proposals for grassland restoration in Mongolian steppe (Special Issue: Overuse and underuse of grassland ecosystems). Journal of Japanese Society of Grassland Science, 59(3), 212–216. [In Japanese] . [CrossRef]

| 2024 | Inside | Outside | ||||||

| active burrow | off-colony area | active burrow | off-colony area | |||||

| Artemisia adamsii | 15.6% | Stipa krylovii | 22.5% | Leymus chinensis | 25.0% | Heteropappus hispidus | 19.5% | |

| Stipa krylovii | 10.0% | Artrmisia frigida | 8.5% | Stipa krylovii | 13.0% | Stipa krylovii | 14.0% | |

| Artemisia dracunculus | 7.2% | Cleistogenes squarrosa | 8.0% | Artemisia glauca | 11.0% | Cleistogenes squarrosa | 10.0% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).