I. Introduction

Accurate assessment of the effectiveness of rehabilitation training is critical to the development of individualized treatment plans. Traditional assessment methods rely on clinical experience and scale scores, which have limitations such as high subjectivity and insufficient data acquisition. The introduction of machine learning technology provides an objective, data-driven means of prediction for rehabilitation training. In this study, we integrated clinical data, image data and physiological signals to construct a prediction model based on supervised and unsupervised learning, and optimized the feature extraction and model training strategies[

1]. Through multi-dimensional data fusion and model performance evaluation, the prediction accuracy and generalization ability are improved. The research results can provide accurate decision support for rehabilitation medicine and promote the development of intelligent rehabilitation technology.

The prediction model constructed in this study holds significant clinical value, particularly in the field of stroke rehabilitation. Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, and timely, accurate evaluation of rehabilitation progress is essential for tailoring effective recovery programs. By integrating clinical data such as neurological assessments, motor function scores, and rehabilitation histories with physiological signals and imaging data, the model can provide objective, real-time predictions of functional improvement in stroke patients. For example, electromyographic (EMG) signals from affected limbs, combined with gait analysis and MRI-based tissue recovery metrics, allow clinicians to quantify motor recovery with high precision. Additionally, electroencephalogram (EEG) data can be used to monitor cortical activity changes associated with neuroplasticity during training. The use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) enhances the analysis of motion patterns and posture dynamics, helping to detect subtle improvements or regressions. This data-driven approach enables early identification of patients who may require modified therapy strategies or more intensive interventions. Furthermore, unsupervised learning methods such as clustering can classify patients into recovery trajectories, facilitating group-based therapy planning and resource allocation. The integration of this predictive model into clinical practice supports evidence-based decision-making, reduces reliance on subjective assessments, and improves rehabilitation outcomes for stroke survivors. As a result, it advances the development of intelligent, personalized rehabilitation medicine.

II. Data collection and Feature Extraction

A. Clinical Data Collection

The collection of clinical data relies mainly on hospital Electronic Medical Records (EMR), rehabilitation center databases, and patient interviews. A total of 216 patients were included in the study, whose data were collected between January 2021 and September 2023 from three tertiary hospitals and two rehabilitation centers in Beijing and Wuhan. The basic information of patients, including age, gender, medical history, surgical records, and drug use, was obtained through the EMR system. Rehabilitation training records, such as program type, frequency, duration, and rehabilitation scores, were extracted from the rehabilitation center database. These variables comprehensively reflect the patient's recovery trajectory [

2]. Clinicians and rehabilitation therapists administered standardized clinical scales (e.g., Fugl-Meyer Motor Function Score, Barthel Index) on a biweekly basis during the 12-week rehabilitation period. Additional data were gathered through monthly follow-up interviews, self-reported forms, and synchronized video recordings. All patient records were de-identified and normalized using standard clinical data formats to ensure privacy protection and consistency in downstream model training [

3].

B. Image Data Acquisition

Image data acquisition is mainly used to analyze the patient's movement patterns, muscle activity and rehabilitation progress, often using 3D motion capture systems, high-speed cameras, medical imaging (MRI, CT) and thermal imaging equipment for data acquisition. In gait analysis, optical motion capture systems such as Vicon or OptiTrack are used to capture the joint point trajectories of the patient during walking, and the data are stored in three-dimensional coordinates in a format such as (

)[

4]. Electromyography (EMG) images were combined with Fourier transform to analyze the muscle contraction frequency, calculated as:

MRI images are used to detect soft tissue recovery, and grayscale histogram analysis quantifies tissue changes, with common metrics including pixel intensity mean

and standard deviation

, calculated with the following formula:

Computer vision techniques (e.g., OpenPose) are used to extract motion keypoints and analyze the postural changes of patients before and after rehabilitation by convolutional neural networks (CNN) to improve the accuracy of the prediction model[

5].

C. Physiological Signal Acquisition

Electrocardiographic signals (ECG) are acquired by 12-lead electrocardiographs or portable ECG monitors, recorded in the bandwidth range of 0.05-150 Hz, with a sampling frequency of typically 250-1000 Hz per second.Electromyographic signals (EMG) are acquired using a surface electromyography transducer (sEMG), where electrodes are placed on the surface of the target muscle group, with a sampling frequency in the range of 1000-2000 Hz, and the signals are Noise was removed by band-pass filtering (20-450Hz)[

6]. Electroencephalographic (EEG) signals, on the other hand, use a high-density EEG cap (e.g., Neuroscan) with a sampling frequency usually in the range of 256 Hz or 512 Hz. blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂) is calculated using pulse oximetry, with measurements taken by infrared and visible light transmission to calculate changes in blood oxygenation. All signals are processed by analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) and stored in time-series data format for subsequent feature extraction and analysis.

D. Feature Engineering

Feature engineering is a key step in building an effective predictive model, aiming to transform raw data into informative inputs that enhance model performance. This process includes data cleaning, feature extraction, dimensionality reduction, and feature selection. For clinical data, normalization techniques such as Z-score normalization are applied to eliminate the influence of scale differences between features. Meanwhile, missing data are handled through mean interpolation or K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) interpolation to maintain data integrity. In terms of image data, high-dimensional features are automatically extracted using convolutional neural networks (CNN), which enables the model to capture complex spatial information. Motion features are further enhanced through edge detection methods like the Sobel operator, as well as keypoint detection techniques such as OpenPose, which provide detailed insights into patient posture and joint movement. For physiological signals, time-frequency domain features are obtained using methods such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), enabling dynamic tracking of signal variations over time. Common metrics like mean, variance, peak-to-peak amplitude, and power spectral density are calculated to capture signal characteristics. To manage the high dimensionality of the dataset and avoid overfitting, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to reduce redundant features, while LASSO regression helps select the most relevant variables[

7]. Finally, all processed features are integrated into a structured dataset and input into machine learning algorithms for model training.

III. Machine Learning Model Construction

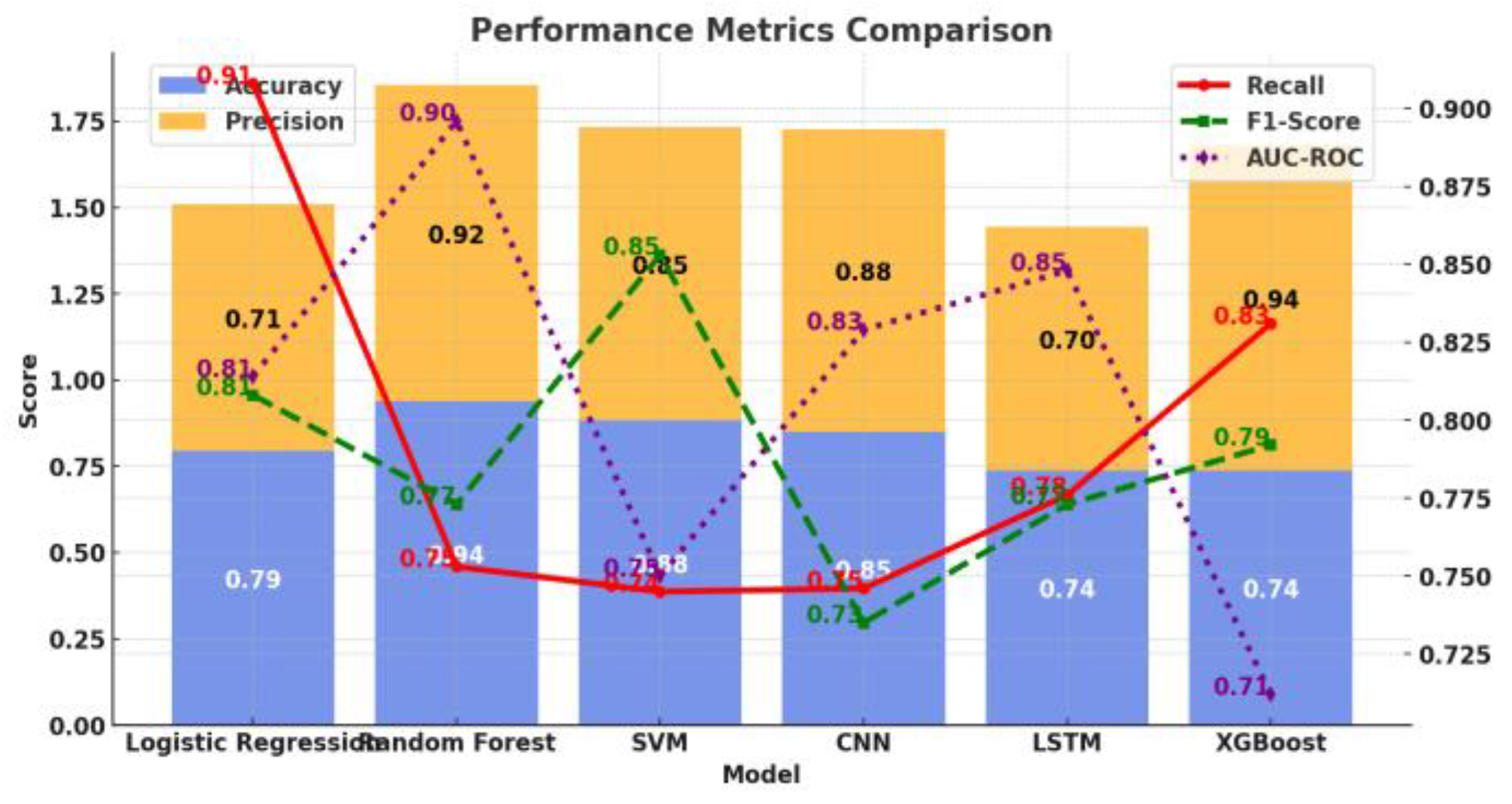

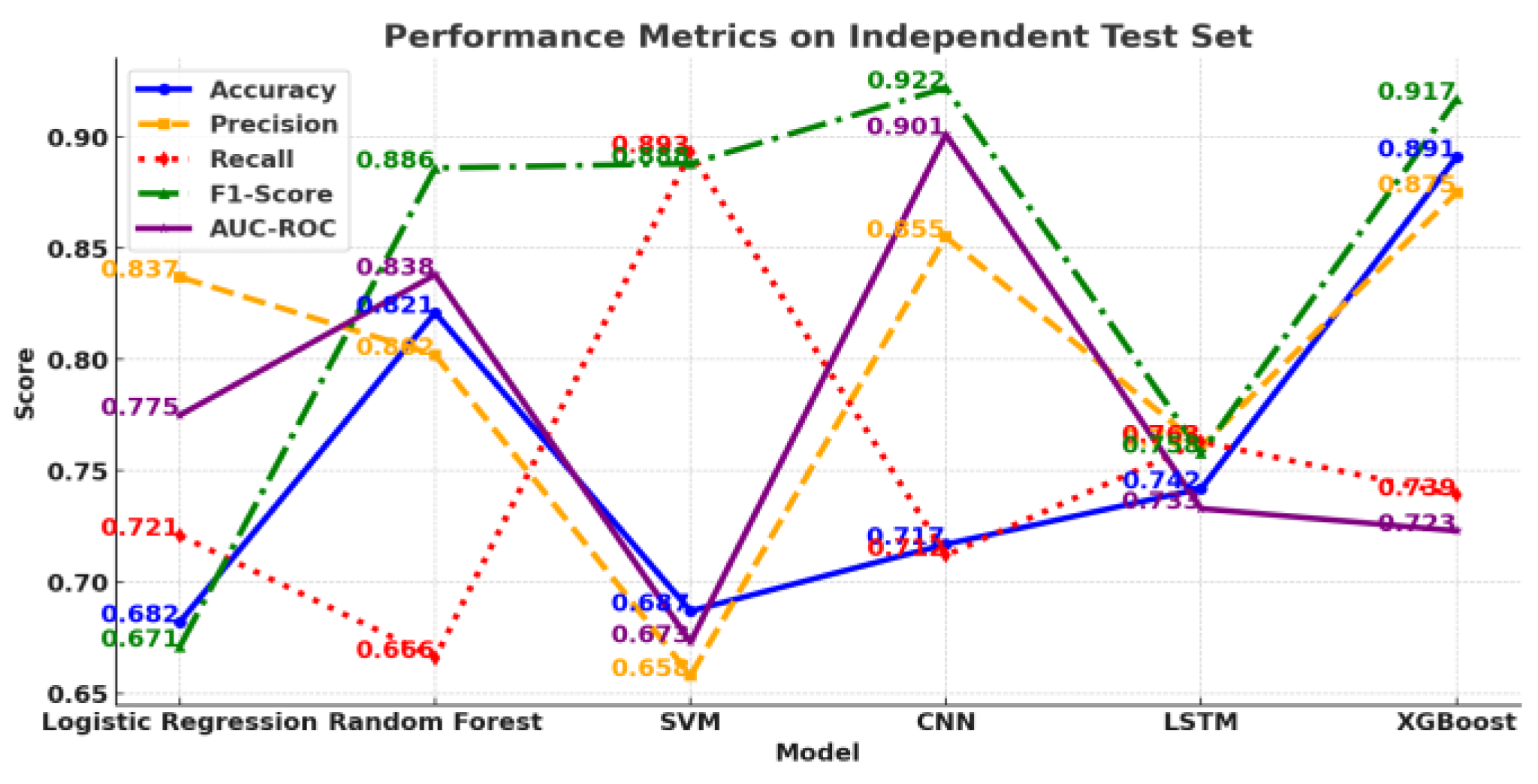

A. Supervised Learning Models

Supervised learning models are mainly used to build a prediction system for rehabilitation training effects, based on labeled data, and common algorithms include Logistic Regression (Logistic Regression), Random Forest (Random Forest), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Deep Learning (CNN, LSTM)[

8].

Logistic regression is suitable for dichotomous tasks such as predicting the success of a patient's rehabilitation, which is mathematically modeled as:

Where, is the input feature and is the weight parameter.

A random forest consists of multiple decision trees, and the final prediction is taken as the average of the votes of each tree[

9].

SVM is used for small samples of high-dimensional data to find the maximum interval hyperplane with the optimization objective:

The novelty of the proposed model lies in its integrated deep learning structure: a hybrid CNN-LSTM model that processes heterogeneous input data types in parallel streams. CNN layers extract high-level spatial features from motion images, while LSTM layers capture temporal dependencies from physiological time-series signals. These representations are then concatenated in a fusion layer, enabling the model to jointly learn spatiotemporal correlations relevant to functional recovery. The architecture supports end-to-end training and benefits from improved convergence and generalization across multiple rehabilitation domains. Optimization is achieved via cross-entropy loss with adaptive learning rate scheduling and dropout regularization, which helps mitigate overfitting in small-to-medium datasets [

10].

B. Unsupervised Learning Models

Common methods include cluster analysis (K-Means, DBSCAN), principal component analysis (PCA), and autoencoder.

K-Means clustering was used to classify patients into different rehabilitation process categories with the goal of minimizing the within-cluster squared error (WCSS):

Where is the first cluster and is the center of the cluster. K-Means needs to set the number of clusters but cannot discover the data structure automatically.

DBSCAN is based on density clustering for non-spherical data and can be used to identify abnormal recovery patients.PCA (Principal Component Analysis) is used for feature dimensionality reduction, projecting high-dimensional physiological signal data into a low-dimensional space in order to preserve the main information and improve computational efficiency. Autoencoder is an unsupervised neural network-based method that learns a low-dimensional representation of the data to help detect abnormal patterns, such as abnormal signals during recovery or extreme recovery cases[

11].

V. Conclusions

A machine learning-based model for predicting the effectiveness of rehabilitation training achieves multimodal feature fusion and improves prediction accuracy by integrating clinical data, motion imagery, and physiological signals. The proposed hybrid architecture, which combines CNN and LSTM modules, represents a novel contribution by enabling joint learning across spatial and temporal modalities. This spatiotemporal fusion mechanism enhances model sensitivity to subtle functional changes and improves robustness across diverse patient profiles.

Beyond conventional supervised modeling, the integration of data-driven weighting strategies, adaptive training schedules, and dimensionality reduction enhances the model’s interpretability and clinical relevance. The architecture’s modularity supports flexible application across different rehabilitation contexts. Future work will focus on expanding clinical datasets, optimizing real-time deployment pipelines, and extending the model to other recovery scenarios such as spinal cord injuries and orthopedic rehabilitation, thereby enhancing its generalizability and translational impac.

References

- Lu, Q.; Wang, M.; Zuo, Y.; et al. Construction and verification of a risk prediction model of psychological distress in psychiatric nurses [J]. BMC Nursing, 2025, 24, 161–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, F.; Zhong, L.; Min, J.; et al. Construction and validation of risk prediction models for renal replacement therapy in patients with acute pancreatitis [J]. European Journal of Medical Research, 2025, 30, 70–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wan, H.; et al. Construction and validation of a nomogram prediction model for the occurrence of complications in patients following robotic radical surgery for gastric cancer [J]. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery, 2025, 410, 54–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba, Q.M.; Zheng, L.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; et al. Construction of a nomogram prediction model for early postoperative stoma complications of colorectal cancer. [J]. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery, 2025, 17, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, N.E.; Huang, J.; Chiu, J.; et al. Development and validation of an EHR-based risk prediction model for geriatric patients undergoing urgent and emergency surgery [J]. BMC Anesthesiology, 2025, 25, 33–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, B.; Pan, C.; Wang, T.; et al. Development and validation of a recurrence risk prediction model for elderly schizophrenia patients [J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2025, 25, 73–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney G D. Development and temporal-validation of prognostic models for 5-year risk of pneumonia, respiratory failure/collapse, and fracture among adults with cerebral palsy. [J]. Advances in medical sciences. 2025; 70, 109–116.

- Huang, J.; Hao, J.; Luo, H.; et al. Construction of a C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte index-based prediction model for all-cause mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. [J]. Renal failure, 2025, 47, 2444396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Metabolism pathway-based subtyping in endometrial cancer: An integrated study by multi-omics analysis and machine learning algorithms [J]. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids, 2024, 35, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Huan, R.; et al. Machine learning unveils immune-related signature in multicenter glioma studies [J]. iScience, 2024, 27, 109317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sıtkı A,Emre Y,Metehan H A. A New Comparative Approach Based on Features of Subcomponents and Machine Learning Algorithms to Detect and Classify Power Quality Disturbances [J]. Electric Power Components and Systems, 2024; 52, 1269–1292.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).