Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Profiling of J. spicigera Extract

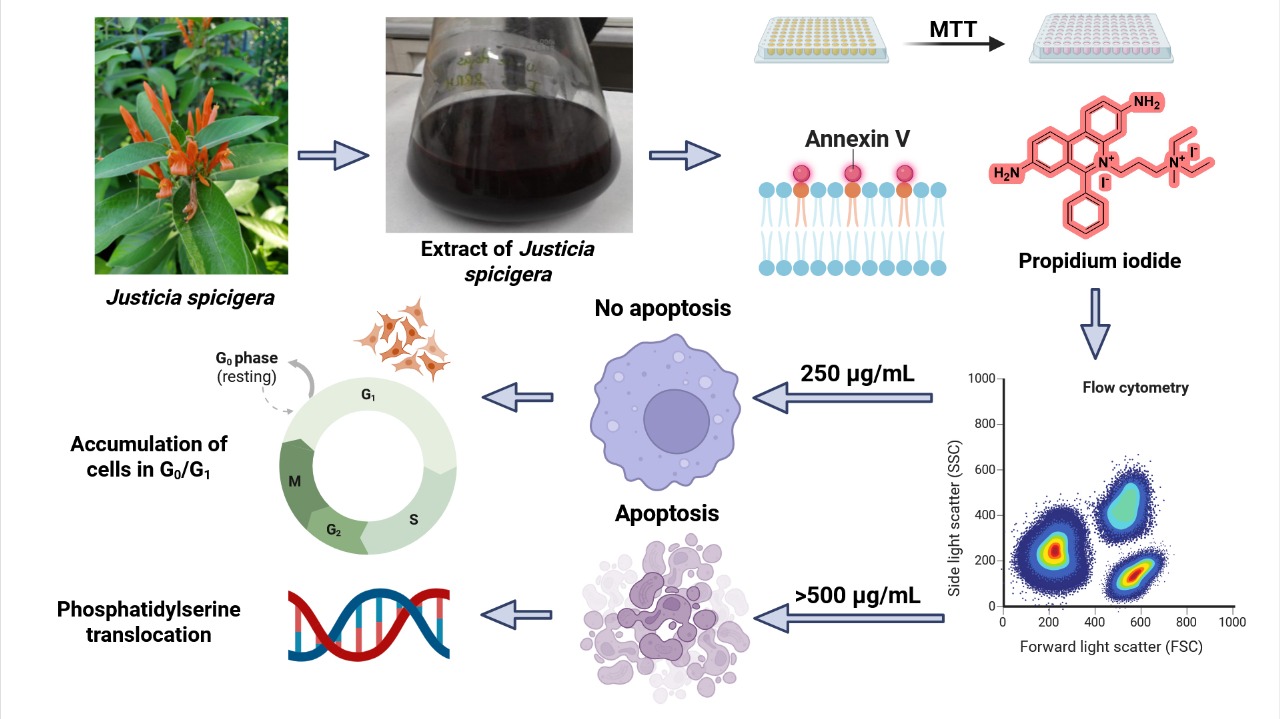

2.2. Effects of J. spicigera on LNCaP Cell Proliferation

2.2.1. MTT Assay

2.2.2. Morphological Characterization of Treated LNCaP Cells

2.2.3. Trypan Blue Assay

2.3. Apoptosis Induction and Cell Viability

2.4. Cell Cycle Arrest Mechanism

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Extract Preparation

4.2. Preliminary Phytochemical Characterization

4.3. Cell Culture and Maintenance

4.4. MTT Assay for Cell Viability

4.5. Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay

4.6. Flow Cytometry for Apoptosis (Annexin V/PI Staining)

4.7. Cell Cycle Analysis (PI Staining by Flow Cytometry)

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raychaudhuri, R.; Lin, D.W.; Montgomery, R.B. Prostate Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignozzi, S.; Santucci, C.; Levi, F.; Malvezzi, M.; Boffetta, P.; Corso, G.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Cancer mortality predictions for 2025 in Latin America with focus on prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Defunciones registradas de hombres por tumor maligno de la próstata por entidad federativa de residencia habitual y grupo quinquenal de edad, serie 2010 a 2023; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2025. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/tabulados/interactivos/?pxq=mortalidad (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- SSA. Boletín Epidemiológico. Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Sistema Único de Información. Dirección General de Epidemiología, Secretaría de Salud: Mexico City, Mexico. 2025, Volume 42. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/direccion-general-de-epidemiologia-boletin-epidemiologico (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Sekhoacha, M.; Riet, K.; Motloung, P.; Gumenku, L.; Adegoke, A.; Mashele, S. Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules 2022, 27, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrance, W.; Dreicer, R.; Jarrard, D.F.; Scarpato, K.R.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; Cookson, M.S. Updates to Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline (2023). J. Urol. 2023, 209, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Canales, M.; Jimenez-Rivas, R.; Canales-Martinez, M.M.; Garcia-Lopez, A.J.; Rivera-Yanez, N.; Nieto-Yanez, O.; Rodriguez-Monroy, M.A. Protective Effect of Amphipterygium adstringens Extract on Dextran Sulphate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 8543561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Armas, J.P.; Arroyo-Acevedo, J.L.; Palomino-Pacheco, M.; Ortiz-Sanchez, J.M.; Calva, J.; Justil-Guerrero, H.J.; Herrera-Calderon, O. Phytochemical Constituents and Ameliorative Effect of the Essential Oil from Annona muricata L. Leaves in a Murine Model of Breast Cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rosas, C.A.; González-Periañez, S.; Pawar, T.J.; Zurutuza-Lorméndez, J.I.; Ramos-Morales, F.R.; Olivares-Romero, J.L.; Saavedra Vélez, M.V.; Hernández-Rosas, F. Anticonvulsant Potential and Toxicological Profile of Verbesina persicifolia Leaf Extracts: Evaluation in Zebrafish Seizure and Artemia salina Toxicity Models. Plants 2025, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Hernández, K. I.; Pawar, T. J.; Ramos-Morales, F. R.; López-Rosas, C. A.; Hernández-Rosas, F. Chemical Duality of Verbesina Metabolites: Sesquiterpene Lactones, Selectivity Index (SI), and Translational Feasibility for Anti-Resistance Drug Discovery. Preprints 2026, 2026011104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.A.; Tabassum, N. Natural product inspired leads in the discovery of anticancer agents: an update. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 8605–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles-Lopez, G.E.; Gonzalez-Trujano, M.E.; Rodriguez, R.; Deciga-Campos, M.; Brindis, F.; Ventura-Martinez, R. Gastrointestinal activity of Justicia spicigera Schltdl. in experimental models. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, M.R.B.; Sallum, L.O.; Martins, J.L.R.; Peixoto, J.C.; Napolitano, H.B.; Rosseto, L.P. Overview of the Justicia Genus: Insights into Its Chemical Diversity and Biological Potential. Molecules 2023, 28, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Cruz-Jimenez, L.; Hernandez-Torres, M.A.; Monroy-Garcia, I.N.; Rivas-Morales, C.; Verde-Star, M.J.; Gonzalez-Villasana, V.; Viveros-Valdez, E. Biological Activities of Seven Medicinal Plants Used in Chiapas, Mexico. Plants 2022, 11, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; León-Becerril, E.; García-Depraect, O. Beyond the Exploration of Muicle (Justicia spicigera): Reviewing Its Biological Properties, Bioactive Molecules and Materials Chemistry. Processes 2022, 10, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Villicana, M.; Noriega-Cisneros, R.; Pena-Montes, D.J.; Huerta-Cervantes, M.; Aguilera-Mendez, A.; Cortes-Rojo, C.; Saavedra-Molina, A. Antilipidemic and Hepatoprotective Effects of Ethanol Extract of Justicia spicigera in Streptozotocin Diabetic Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garza, N.E.; Quintanilla-Licea, R.; Romo-Saenz, C.I.; Elizondo-Luevano, J.H.; Tamez-Guerra, P.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C.; Gomez-Flores, R. In Vitro Biological Activity and Lymphoma Cell Growth Inhibition by Selected Mexican Medicinal Plants. Life 2023, 13, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Cabanas-Wuan, A.; Arana-Argaez, V.E.; Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Zapata-Bustos, R.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Antidiabetic effects of Justicia spicigera Schltdl (Acanthaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vasquez, A.; Diaz-Rojas, M.; Castillejos-Ramirez, E.V.; Perez-Esquivel, A.; Montano-Cruz, Y.; Rivero-Cruz, I.; Mata, R. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitory activity of compounds from Justicia spicigera (Acanthaceae). Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arberet, L.; Pottier, F.; Michelin, A.; Nowik, W.; Bellot-Gurlet, L.; Andraud, C. Spectral characterisation of a traditional Mesoamerican dye: relationship between in situ identification on the 16th century Codex Borbonicus manuscript and composition of Justicia spicigera plant extract. Analyst 2021, 146, 2520–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, X.A.; Aguilar, H.; González, C.; Ferreé-D'Amare, A.R. Estudio químico del "muitle" (Justicia spicigera). Rev. Latinoamer. Quím. 1990, 21, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, K.L.; Alam, M. Isolation of Kaempferitrin From Justicia spicigera. J. Nat. Prod. 1982, 45, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Morales, J.R.; Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Gonzalez-Rivera, M.L.; Gonzalez Prado, H.I.; Barragan-Galvez, J.C.; Hernandez-Flores, A.; Ramirez-Morales, M.A. Synergistic Interaction Between Justicia spicigera Extract and Analgesics on the Formalin Test in Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, N.E.; Abdelkawy, M.A.; Abdel Rahman, E.H.; Hamed, M.A.; Ramadan, N.S. Phytochemical and in vitro Screening of Justicia spicigera Ethanol Extract for Antioxidant Activity and in vivo Assessment Against Schistosoma mansoni Infection in Mice. Anti-Infective Agents 2018, 16, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, N.; Khan, W.; Md, S.; Ali, A.; Saluja, S.S.; Sharma, S.; Al-Ghamdi, S.S. Phytosterols as a natural anticancer agent: Current status and future perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 88, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres-Cortes, J.R.; Cantu-Garza, F.A.; Mendoza-Mata, M.T.; Chavez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Ramos-Mandujano, G.; Zambrano-Ramirez, I.R. Cytotoxic activity of Justicia spicigera is inhibited by bcl-2 proto-oncogene and induces apoptosis in a cell cycle dependent fashion. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Avila, E.; Tapia-Aguilar, R.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, S.L.; Pérez-Flores, J.; Velasco-Lezama, R. Actividad antibacteriana y antifúngica de Justicia spicigera. Rev. Latinoam. Quím. 2012, 40, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo-Salcedo, M.d.R.; Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Carranza-Alvarez, C.; González-Espíndola, L.Á.; Domínguez, F.; García-Carrancá, A. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Effects of Mexican Medicinal Plants. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 1934578X1100601234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Vázquez, M.C.; Alonso-Castro, A.J.; García-Carrancá, A. Kaempferitrin induces immunostimulatory effects in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrance, W.; Dreicer, R.; Jarrard, D.F.; Scarpato, K.R.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; Cookson, M.S. Updates to Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline (2023). J. Urol. 2023, 209, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, E.L.; Arbuck, S.G.; Pluda, J.M.; Simon, R.; Kaplan, R.S.; Christian, M.C. Clinical trial designs for cytostatic agents: are new approaches needed? J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pomares, C.; Juárez-Aguilar, E.; Domínguez-Ortiz, M.Á.; Gallegos-Estudillo, J.; Herrera-Covarrubias, D.; Sánchez-Medina, A.; Hernández, M.E. Hydroalcoholic extract of the widely used Mexican plant Justicia spicigera Schltdl. exerts a cytostatic effect on LNCaP prostate cancer cells. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 12, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Ortiz-Sanchez, E.; Garcia-Regalado, A.; Ruiz, G.; Nunez-Martinez, J.M.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, I.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Kaempferitrin induces apoptosis via intrinsic pathway in HeLa cells and exerts antitumor effects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S. Kaempferitrin Regulates the Proliferation, Metastasis, and Immune Escape of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer by Inhibiting the Akt/NF-κB Pathway. Drug Dev. Res. 2025, 86, e70117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Jakstas, V.; Savickas, A.; Bernatoniene, J. Flavonoids as Anticancer Agents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Khan, H.; Zia, A.; Khan, A.; Fakhri, S.; Aschner, M.; Saso, L. Bcl-2 Modulation in p53 Signaling Pathway by Flavonoids: A Potential Strategy towards the Treatment of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, S.; Zeng, A.; He, S.; Jin, X.; Li, C.; Lu, Q. Inhibitory Effect of β-Sitosterol on the Ang II-Induced Proliferation of A7r5 Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells. Anal. Cell. Pathol. (Amst) 2023, 2023, 2677020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elasbali, A.M.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Al-Oanzi, Z.H.; Qanash, H.; Alharbi, B.; Binsaleh, N.K.; Adnan, M. Cytotoxic Activity, Cell Cycle Inhibition, and Apoptosis-Inducing Potential of Athyrium hohenackerianum (Lady Fern) with Its Phytochemical Profiling. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 2022, 2055773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.B.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Yao, W.J.; Wei, L. Lotus leaf flavonoids induce apoptosis of human lung cancer A549 cells through the ROS/p38 MAPK pathway. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Liska, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Flavonoids and their role in oxidative stress, inflammation, and human diseases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 413, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Xu, L.; Huang, M.; Deng, B.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yinzhi, S. β-Sitosterol Protects against Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via Targeting PPARγNF-κB Signalling. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2020, 2020, 2679409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, J. Kaempferitrin, a major compound from ethanol extract of Chenopodium ambrosioides, exerts antitumour and hepatoprotective effects in the mice model of human liver cancer xenografts. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Kamarudin, M.N.A.; Naidu, R. Anticancer Mechanism of Flavonoids on High-Grade Adult-Type Diffuse Gliomas. Nutrients 2023, 15, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Su, M.; Ren, Y.; Shang, H. Potential anti-liver cancer targets and mechanisms of kaempferitrin based on network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental verification. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 108693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Pan, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, J. Kaempferitrin alleviates LPS-induced septic acute lung injury in mice through downregulating NF-κB pathway. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr). 2023, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Bax and Bak genes are essential for maximum apoptotic response by curcumin, a polyphenolic compound and cancer chemopreventive agent derived from turmeric, Curcuma longa. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Wu, J.M. Differential effects on growth, cell cycle arrest, and induction of apoptosis by resveratrol in human prostate cancer cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 1999, 249, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, A.; Kim, S.H.; Hwang, C. Androgen receptor negatively regulates mitotic checkpoint signaling to induce docetaxel resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate 2022, 82, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meerloo, J.; Kaspers, G.J.; Cloos, J. Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 731, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Hu, Y. LNCaP-AI prostate cancer cell line establishment by Flutamide and androgen-free environment to promote cell adherent. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3.B.1–A3.B.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, I.; Batra, S.K. Protocol for Apoptosis Assay by Flow Cytometry Using Annexin V Staining Method. Bio Protoc. 2013, 3, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Sederstrom, J.M. Assaying Cell Cycle Status Using Flow Cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2015, 111, 28.6.1–28.6.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.