1. Introduction

Nowadays, virtually all industrial processes cause disturbances in their surroundings due to logistical or environmental issues. This is one of the reasons why, whenever possible, industrial zones are usually located on the outskirts of urban areas. Concentrating or isolating activities helps, to some extent, to implement corrective measures to mitigate potential effects on the population.

From the perspective of environmental acoustics, authorities legislate more leniently on the maximum noise limits that industries can emit in the vicinity of their facilities. This assumes that industrial processes generate sound disturbances greater than those experienced in everyday urban life, with differences ranging between 10-20 dB between zones [

1,

2,

3]. Although legislation is somewhat more permissive, controlling emission levels is necessary and mandatory.

Noise sources in the industrial sector can be countless, but it is common to find internal combustion engines, such as electric generators or driving elements, which generate significant levels of noise pollution due to their operating principles. There are two main sources of noise in combustion engines: the combustion roar or roar of the engine [

4], which results from its operation in stable conditions; and the thermoacoustic instability’s noise, that is related to the fluid oscillations that occur during combustion.

The combustion noise is the main one in Diesel engines [

5,

6]. It depends on several operating parameters such as speed, load, injection strategy, fuel composition or ignition delay.

The first idea about diesel engine noise was the importance of the time variation of the pressure inside each cylinder and that’s right: noise is highly consistent with cylinder pressure [

7]. But it has been proved by means of experimental studies that noise is caused largely by the randomness of combustion: the cylinder pressure is dominated by randomness over a wide range of frequencies where noise is produced.

Fluctuation in combustion can be increased if the engine work has been optimized, for example, to minimize fuel consumption or achieve a certain quality of exhaust gas. The effects associated with low load were not present (ignition effect, speed control in idle type operation). The results show that combustion dynamics is a non-linear, multidimensional process mediated by noise [

8,

9,

10].

When considering combustion as a source of noise, Duran and other authors [

11,

12,

13] identified two main generation mechanisms:

Direct combustion noise, in which the acoustic waves generated by the flame propagate towards the exhaust. It usually has its main amplitudes in low frequencies and in a few preferential frequencies. Direct noise is generated and irradiated from a region in turbulent combustion. It is caused by a temporary fluctuation in the release of total heat in the reaction region. Although this fluctuation is small, it can generate pressure waves.

Indirect combustion noise, also called "entropy noise", which is due to entropy waves. The entropy waves are associated with hot spots, which entropy level is different from that of the surrounding environment. The acceleration of entropy waves generates pressure fluctuations that propagate upflow and downflow. When positive feedback occurs, they contribute to the instability of combustion.

Although the combustion noise and its stability are related, the dominance of direct or indirect noise does not depend on the stability / instability conditions of combustion but on the nature of the device [

14].

Strahle [

7] noted that molecular weight differences or specific heat variations could produce analogous effects, though recent studies show these factors are secondary to thermal gradients in modern combustors, where temperature fluctuations exceed 300 %. Indirect noise arises downstream of the combustion zone due to thermal inhomogeneities ("hot/cold spots") interacting with components like turbine blades. Large Eddy Simulations (LES) in transonic nozzles confirm that entropy waves contribute up to 40 % of total acoustic noise in gas turbines, particularly under unsteady flow conditions [

15]. In homogeneous flows, noise combines three wave types:

1. Acoustic waves (propagating at sound speed),

2. Turbulent convective waves,

3. Entropy convective waves.

When accelerated through variable geometries (e.g., convergent-divergent diffusers), entropy waves generate fluctuating forces equivalent to acoustic dipoles, radiating sound at 80–500 Hz in annular combustors. This mechanism, termed entropy noise, dominates over direct noise in aviation turbines under partial load [

16].

Thermoacoustic instabilities stem from phase-amplitude coupling between pressure oscillations and heat release. The Rayleigh Index, spatiotemporally integrated, quantifies this coupling: positive values indicate perturbation amplification. Experimental studies in premixed burners reveal this index remains positive under steady conditions, even with out-of-phase responses, due to flame nonlinearities [

17]. In rocket engines, this phenomenon generates 1–5 kHz longitudinal modes, mitigated via modulated acoustic injection [

18].

Pressure oscillations modulate injector mass flow rates, creating positive feedback. In full annular combustors, LES simulations show 70 % of acoustic energy concentrates in first-order transverse modes (200–800 Hz), requiring active strategies like aeroacoustics valves for suppression [

19]. Adaptive control systems, using piezoresistive microphones and membrane actuators, achieve 18 dB reductions in exhaust noise through destructive interference of low-frequency waves (<500 Hz) [

20].

Three situations can be differenced [

8]:

- Low frequency oscillations (from 4 Hz to 70 Hz) are mainly due to instabilities in the flame front when it does not progress homogeneously throughout the combustion chamber. As these phenomena have high time constants, they are related to low frequency emissions.

- From 70 Hz to 700 Hz stationary waves with different phase angles appear. The time constants of these phenomena are from 3 ms to 6 ms.

- Phenomena related to high frequency components have time constants of the order of 0.5 ms.

It should be noted that, at a first glance, the rotational frequencies of the motors and generators are within the proper range for flame front fluctuations. A coupling between this phenomenon and the operating frequencies of the equipment could result in significant noise emissions.

When working with large machines, avoiding strong simplifications is mandatory. It is not possible to assume that neither phenomena are instantaneous nor the distribution of fuel into the cylinders is homogeneous or similar simplifications.

2. Materials and Methods: Case Study

2.1. Description

This case study refers to a set of 8 engines of 10 MW of nominal power each, installed in an urban area. They were reconverted 4-cycle Diesel engines of 12 cylinders which generate alternating current at 50 Hz. As the generators have 6 pairs of poles, they rotate at 500 rpm (8.3 Hz). Two years later than their installation, the engines needed another important modification to meet the NOx emission specifications. Thus, the cylinders’ chambers were modified and a turbocharger group operating at 25,500 rpm (425 Hz) was installed in each engine. No more problems with NOx emissions were reported. But sometime later, non-expected behaviors related to the acoustic emissions from the engines were perceived. Particularly, a “random variability” of sound pressure levels emitted by those large engines operating in the same conditions with only a few hours of difference was recorded in many opportunities [

21].

The engines we studied were 4-stroke diesel engines; the fuel is ignited by the high compression generated within the combustion chamber. Its idealized thermodynamic cycle is as follows: one useful power stroke every two revolutions, i.e., each cylinder explodes every two revolutions of the crankshaft. The engine speed is 500 rpm (8.3 Hz), with automatic regulation that adjusts the frequency to ±1 % of the nominal value. Assuming that the acoustic emissions of interest are generated in each engine combustion chamber, a response at a frequency like 3,000 explosions/min or 50 per second would be expected (six pistons exploding at 500 rpm). Air is taken from the outside through ducts that pass through the chamber walls and is filtered before being admitted to the engine. The fuel entering each cylinder varies according to the engine’s operating conditions, controlling the maximum compression pressure. Each engine has an individual passive silencer at the outlet and an individual exhaust stack, 60 m high [

21].

There is a certain symmetry in the location of the engines. They are installed in two lines of four. The ducts leading to the stacks are symmetrical. The chimneys, approximately 1.5 m in diameter, are made of thermal iron and clad with sheet metal. Two of the engines also have a heat recovery boiler in their exhaust system, which harnesses the thermal energy of the exhaust gases to produce steam, which is used for specific services, such as reducing the viscosity of the fuel used in combustion [

21].

Under normal operating conditions, any machinery with rotating elements often produces acoustic emissions that are related to the rotation frequency. Thus, gears and bearings are among the better-known noise sources. Tonal components associated with the number of blades and the speed of rotation usually appear in turbomachines; it is the case of turbines and compressors. The number of cylinders and the speed of rotation of internal combustion engines can also introduce pure tones in their acoustic emission spectrum.

The noise is caused largely by the randomness of combustion.

Depending on the difference between the convection and acoustic times, the entropy waves can be coupled in a constructive or destructive way with the acoustics of the combustion chamber. However, qualitative analysis does not arise if the coupling between entropy and acoustic waves is strong enough to significantly influence thermoacoustic stability. In general, combustion instability can be understood as the result of a resonant interaction between at least two oscillatory mechanisms in the system: an excitation mechanism and a feedback effect. The relative phase between the acoustic signal at the combustion chamber outlet and the pressure pulse generated by the entropy wave determines whether the combustion chamber’s susceptibility to thermoacoustic oscillations is improved or reduced by this interaction of the entropy waves with the acoustics of the combustion chamber. The case we present had no instabilities in the releasing of heat (measured as power generation), but there were thermoacoustic instabilities in the combustion chambers [

21].

According to Schuermans (2003) [

22], fluctuations in fuel concentration are the main (but not the only) cause of the interaction between the heat release and the sound field. The crux of the problem is that all the ideal processes under which combustion is studied in small machines are no longer valid in large ones. The hypotheses about instantaneous ignition, homogeneity of the mixture and all phenomena occurring inside of each cylinder are no longer applicable.

Thermoacoustic oscillations cause increased wear on the motors. The high sound pressure levels associated with the oscillations that occur in the case of a thermoacoustic instability impose an additional mechanical load on the wall of the combustion chamber. In addition, non-stationary flow increases heat transfer to the coating and local overheating may occur. Even electronic systems that control combustion can fail due to high levels of vibration or temperature, which would lead to loss of system control. Clearly, thermoacoustic instabilities are an undesirable phenomenon in every combustion chamber.

2.2. Field Measurements

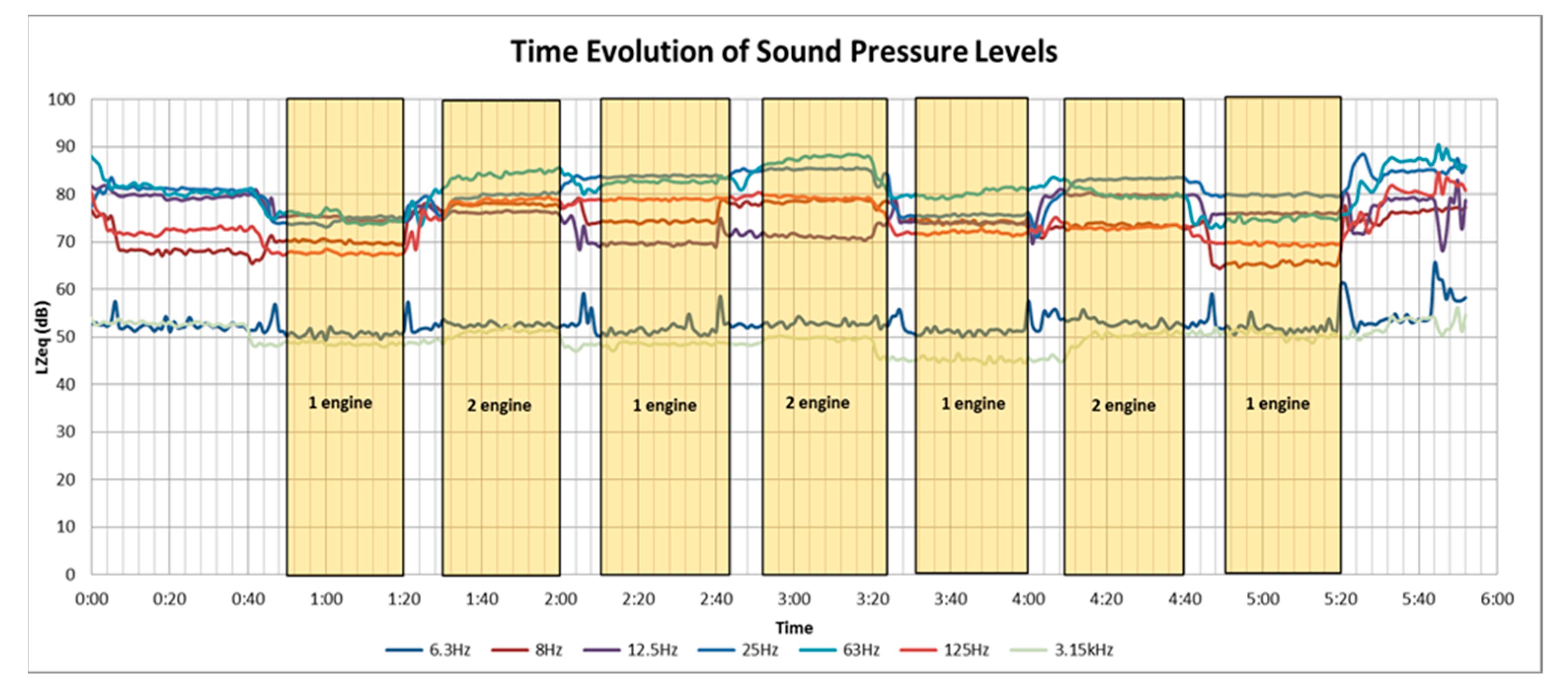

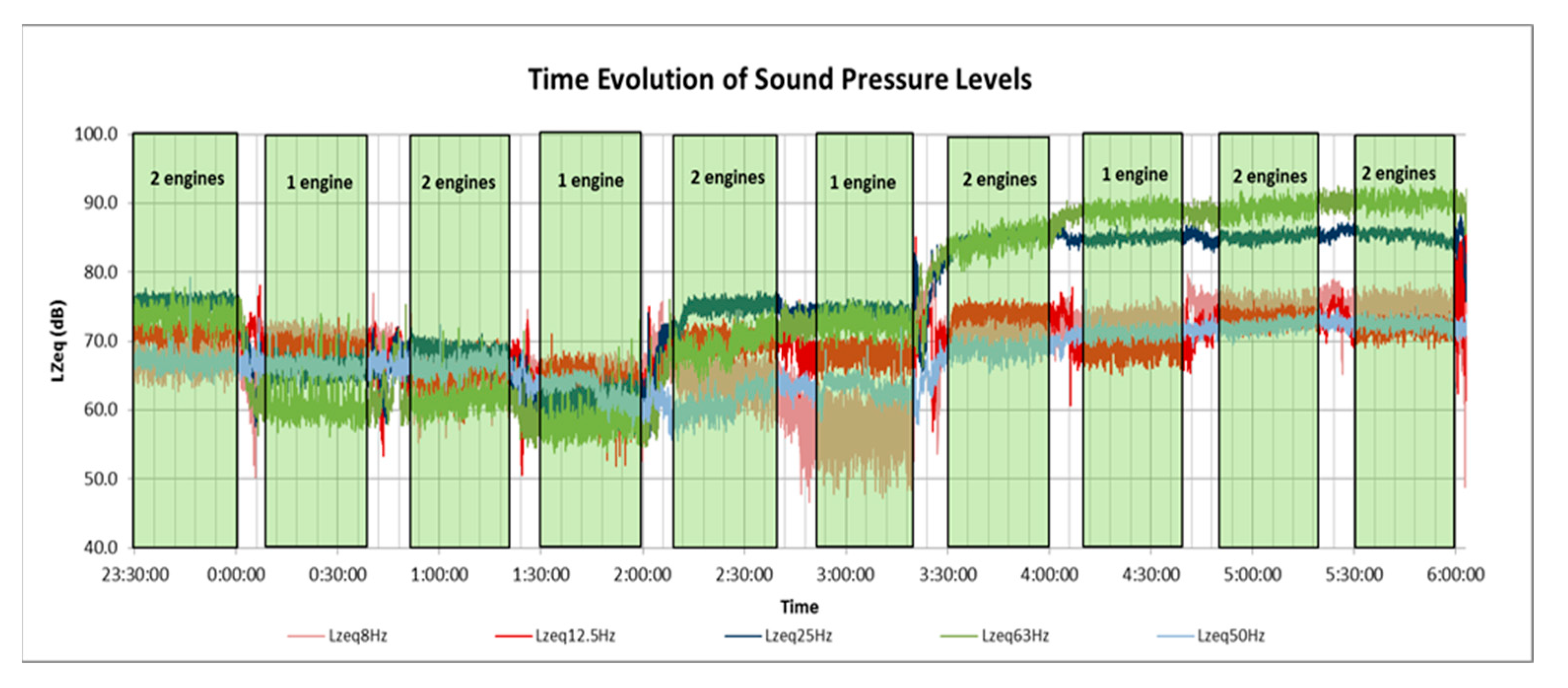

First, some operation tests were done. These operation tests consisted of a predesigned time sequence of turning the engines on and off one by one with simultaneous recordings of sound pressure levels at third-octave bands (TOB) at three different points. Using a precise sequence, one of the engines was turned on and ran for 30 minutes; then, a second engine was turned on and the two engines ran together for 30 minutes; after this period, the first engine was turned off and the second one ran alone for 30 minutes; and so on, until a sequence was completed in which all the engines were recorded running alone for 30 minutes [

22].

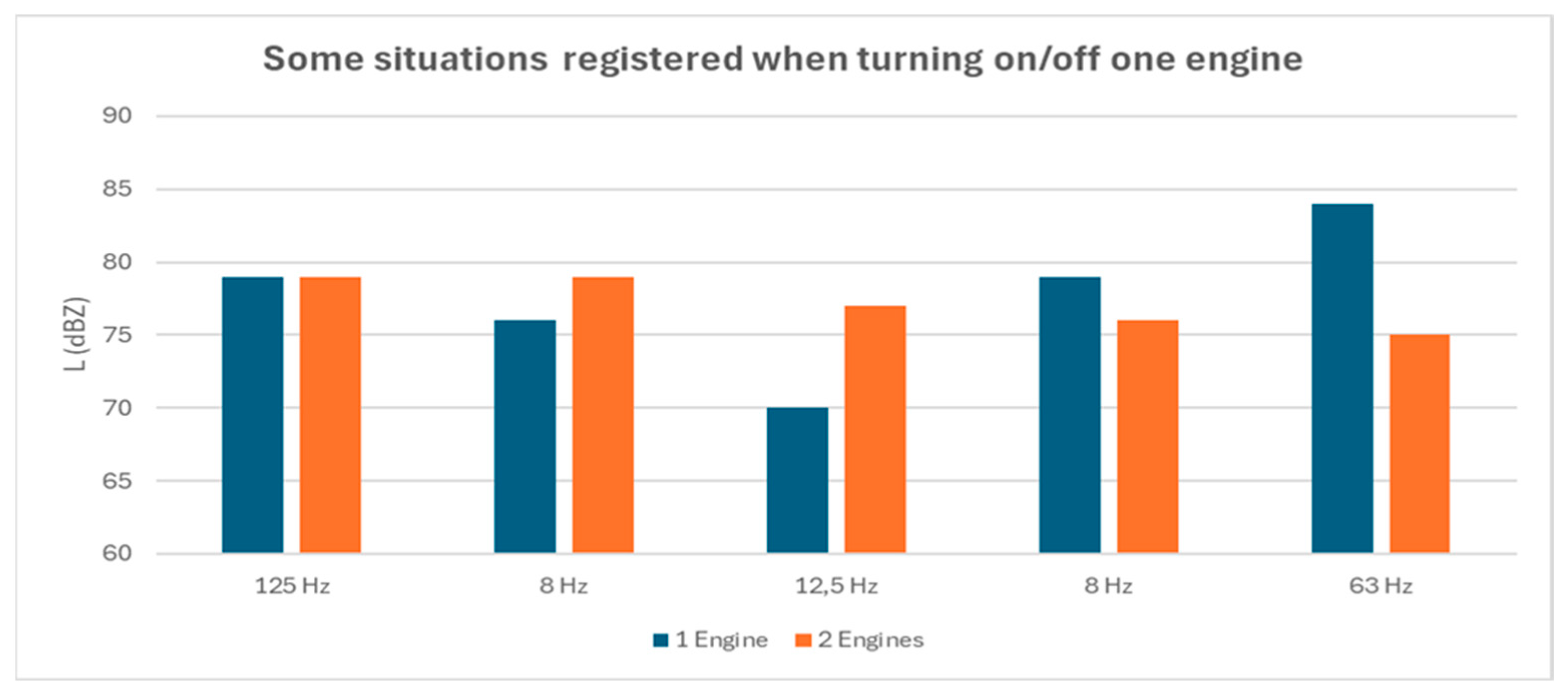

The first surprising results were found when processing the measured data. Thus, we found that in some TOB and in the closest measuring point (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3):

The sound pressure levels did not change when turning off one engine.

The sound pressure levels decreased 3 dB –as expected- when turning off one engine.

The sound pressure levels decreased more than 3 dB when turning off one engine.

The sound pressure levels increased 3 dB when turning off one engine.

The sound pressure levels increased more than 3 dB when turning off one engine.

The sound pressure levels emitted by the same engine could largely differ in different tests. Not only the emitted sound pressure levels changed but also the main TOB when switching on or off did. It is particularly interesting to note the differences in emission spectra of the same engine in the same running conditions for two 30-minute episodes: the differences were as high as 10 dB, and there were both differences in favor or against of the first and second experiments. Also, when comparing measured and calculated sound pressure levels, we found that results differed to the expected ones. The largest differences were found at TOB of 25 Hz, 63 Hz and 125 Hz. We also analyzed some registers taken into de engines room. We found that for the same configuration and generated power, some TOB showed important fluctuations that were not seen in the broad band registers [

21].

The second step in the research was to determine the acoustic power of each of the engines according to the methodology established in ISO Standard 3744:2010 [

23]. A Class 1 (according to IEC 61672 Standard) Bruel&Kjaer sound pressure level meter (Model 2250) was used, with its tripod and a pole for measuring at the elevated positions. Also, the environmental sound pressure levels in the engines room were recorded during the tests.

Since the first test to measure the acoustic power of each engine, we observed large fluctuations in the engines’ fuel inlet pressure. The information about this phenomenon was not publicly available in the control system of the engines. Even though, it was clear that those large fluctuations in the pressure in the fuel inlet line were an unmistakable sign of the occurrence of instabilities in the combustion. As it is stated in the bibliography, the modification in any conditions in the combustion results in a modification in the associated acoustic emissions due to that the conditions of generation of the emission are modified; thus, when the combustion chambers were modified it should have been expected these phenomena to occur.

We were therefore faced with two problems: how to predict the instabilities that would occur and how to control the noise emission due to these instabilities.

When emissions were spontaneously controlled, some frequencies showed a rather symmetric pattern, as it can be seen in

Figure 4.

3. Results

Previous to each of the instability events, it could be observed a special pattern in the frequencies of 25 Hz and 50 Hz, related to “loss of chaos”. This issue was studied by Vinneeth et al. (2013) [

24]. The authors proposed to predict the passage to unstable conditions by a 0-1 test for chaos on sequentially acquired pressure measurements. It demonstrated to be an effective and objective measure of the proximity of the instability, without dependence on the geometry, the fuel or other particular features. Typical episodes of loss of chaos are shown in Figures 5–7 (the figures correspond to the environmental registers at the engines room during the tests for determining the acoustic power of each engine according to ISO 3744:2010 Standard, [

23]). As it can be seen, the process of loss of chaos lasts many minutes before the instability is installed. This is an important point to remark, regarding the possibility of control the system with an active noise control (ANC) solution.

Figures 6, 7 and 8.

Loss of chaos in different third-octave bands during the installation of thermoacoustic instability episodes. Graphs from the environmental sound pressure meter in the engines room. The tests according to ISO 3744 [

23] were carried out during these measurements (only one engine in operation). Please note the ordered pattern before the jump in the sound pressure levels in the considered band.

Figures 6, 7 and 8.

Loss of chaos in different third-octave bands during the installation of thermoacoustic instability episodes. Graphs from the environmental sound pressure meter in the engines room. The tests according to ISO 3744 [

23] were carried out during these measurements (only one engine in operation). Please note the ordered pattern before the jump in the sound pressure levels in the considered band.

4. Discussion

A better acoustic behavior of the engines with recovery boilers was observed, which is described in the literature as a recommended and implemented measure to control noise emissions in medium and high frequencies. However, it was possible to confirm, as expected, that, although the average and high frequencies are effectively controlled by the recovery boiler, which acts as a passive in-line silencer, the low frequencies are not controlled by this type of device.

Control Proposal:

The control of the sound emissions that occur due to the episodes of thermoacoustic instability should be approached as a control of the instabilities themselves, tending not to occur. This means that the control must be exercised at the source and for this it is necessary to resort to active noise control systems. It is not improper to emphasize that control in the path of propagation by conventional passive methods (silencers) does not solve the problem.

The most recommended integral control is the use of systems that combine active and passive elements, which are called hybrid systems: the conventional passive control at the output of the system to reduce the acoustic energy in medium and high frequencies; and active noise control at source to attack low frequencies and even prevent instability from occurring. For example, the use of recovery boilers -like two of the motors have- is a recommended passive control method; however, it does not allow the control of emissions at low frequencies [

21].

In an ANC system, the essential element is the controller, which is the one that "makes the decisions" based on the information received from the different sensors. This is where efforts must be focused to achieve an effective and robust system. One of the central aspects should be the possibility of early detection of conditions leading to the occurrence of instability, such as loss of chaos, and the ability to act in time to modify such conditions before the undesired phenomenon occurs. ANC systems aim to emit a new wave whose nodes coincide with those of the main wave to be controlled, but the phases are inverted. When adding two equal waves in phase and in counterphase, they would be cancelled, and they should give a new wave that is practically zero. Both sources, the main one and the control system, must be separated no more than 0,3 λ. Considering the frequencies involved, which are low ones, it is practically achievable without difficulties (for example, to control a 25 Hz wave, the distance between the two sources must be at least 4 m. The best result should be achieved for 0,1 λ) [

21].

We proposed to use a system with feedforward control, for which it is recommended to emphasize in the best possible design of the control system to assure the success of the design, therefore it is recommended to develop an adaptive control that offers the greatest flexibility and potentiality to the system. The detection sensor would be on the pressure line that will communicate with the controller to emit the reverse wave when the loss of chaos is detected, just before the instability occurs. We found there are several minutes between the loss of chaos and the instability occurring, so it is possible to successfully implement the solution by controlling the time to emit the control sound signal at the right place and time. The application of existing sensor systems for the benefit of early detection and control of the problem is inescapable. For example, records of pressure fluctuations in the fuel supply system could significantly help to decide when to take actions.

5. Conclusions

The diagnosis of the main problem in the case study was not easy. When we arrived to understand there were acoustic instabilities occurring in the combustion chambers, all the pieces of the jigsaw appeared to be coherent and also the solution was clear.

Regarding the different stable (random) and unstable states of running lasts several minutes, as so the transition from one to another does, there was a clear proposal of noise control with a hybrid system. Every quasi-stationary condition before and after the occurrence of a thermoacoustic instability episode lasts some minutes, so active noise control systems seem to be a suitable solution to address the problem. We proposed an ANC system with feedforward control to get rid of the thermoacoustic instabilities; time for the controller to act was more than sufficient (minutes, rather than seconds).

Even though, the company rejected the idea of implementing such an innovative solution, with basis on administrative arguments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AEG, PGK and HCV; methodology, AEG; field data, PGK; formal analysis, AEG and PGK; investigation, AEG, PGK and HCV; data curation, AEG and PGK; writing—original draft preparation, AEG, PGK and HCV; writing—review and editing, AEG, PGK and HCV; supervision, AEG; project administration, AEG; funding acquisition, AEG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a technical assistance contract between Fundación Julio Ricaldoni and the National Energy Agency.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to contract restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANC |

Active Noise Control |

| LES |

Large Eddy Simulation |

| TOB |

Third Octave Band |

References

- Real Decreto 1367/2007, de 19 de octubre, por el que se desarrolla la Ley 37/2003, de 17 de noviembre, del Ruido. (2007). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). Recuperado de. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-18397.

- Norma Técnica Ecuatoriana NTE INEN-ISO 1996-2:2025. (2025). Registro Oficial del Ecuador. Recuperado de. Available online: https://www.lexis.com.ec/noticias/registro-oficial-del-dia-se-oficializa-nueva-norma-tecnica-sobre-medicion-del-ruido-ambiental.

- DOF México. (2025). Acuerdo por el que se modifica el numeral 5.4 de la Norma Oficial Mexicana sobre ruido ambiental. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Recuperado de. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle_popup.php?codigo=5324105.

- Gentil, Y. , Daviller, G., & Moreau, S. (2024). Combustion noise modelling re-examined for thermally perfect and multi-species gas flows. AIAA Aviation Forum. [CrossRef]

- Sawilam, M. , Babaa, S., Haddabi, A., Wasiu, S., Hussain, T., Khzouz, M. and Pillia, J. (2023) Noise Control Solutions for Diesel Generator Sets. Journal of Power and Energy Engineering, 11, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Zhang, S., Kang, N., & Hu, W. (2020). Noise exposure level of coal-fired thermal power stations in different scales - China, 2017-2019. China CDC Weekly, 2(32), 605–608. [CrossRef]

- Strahle, Warren C. (1978) Combustion Noise. Journal of Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, JPECS V. 4 N. 3-A, pp. 157-176, Pergamon Press Ltd., 1978, Great Britain.

- Litak, G. , Taccani, R., Radu, R., Urbanowicz, K., Hołyst, J. A., Wendeker, M., & Giadrossi, A. (2005). Estimation of a noise level using coarse-grained entropy of experimental time series of internal pressure in a combustion engine. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 23, 1695–1701.

- Liu, J. , Li, X., & Yang, Z. (2020). Nonlinear dynamics of combustion instability and noise in low-load diesel engines. Applied Energy, 278(1), 115732. [CrossRef]

- Payri, R. , Broatch, A., Serrano, J. R., & García-Afonso, O. (2023). Correlación entre la presión en cilindro y el ruido de combustión en motores diésel modernos: efectos de la optimización termodinámica. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 548(1), 117569.

- Durán, I. , & Moreau, S. (2011). Analytical and numerical study of the Entropy Wave Generator experiment on indirect combustion noise. Proceedings of the 17th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. [CrossRef]

- Kings, N., & Hochgreb, S. (2019). Direct and indirect noise generated by entropic and compositional inhomogeneities. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, 141(4), 041029. [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, F., Rolland, E. O., & Hochgreb, S. (2019). Detection of direct and indirect noise generated by synthetic hot spots in a duct. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 446, 170-190. [CrossRef]

- Özgür, C. , Uludamar, E., Soyhan, H. S., & Raja Ahsan Shah, R. M. (2024). Optimisation of exhaust emissions, vibration, and noise of unmodified diesel engine fuelled with canola biodiesel-diesel blends with natural gas addition by using response surface methodology. Science and Technology for Energy Transition, 79, 37. [CrossRef]

- Ceci, A., Gojon, R., & Mihaescu, M. (2019). Large Eddy Simulations for Indirect Combustion Noise Assessment in a Nozzle Guide Vane Passage. Flow, Turbulence and Combustion, 102(2), 299–311. [CrossRef]

- Morgans, A. S. (2016). Entropy noise: A review of theory, progress and challenges. International Journal of Spray and Combustion Dynamics, 8(4), 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Schuermans, B., Moeck, J., & Noiray, N. (2022). The Rayleigh integral is always positive in steadily operated combustors. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 39(1), 4321–4329. [CrossRef]

- Bennewitz, A. , & Müller, K. (2022). Modulated acoustic injection for reducing thermoacoustic oscillations in liquid-fueled engines. Journal of Propulsion and Power, 38(2), 567–578.

- Livebardon, T., Moreau, S., & Poinsot, T. (2015). Numerical investigation of combustion noise generation in a full annular combustion chamber. AIAA Journal, 53(6), 2971–2983. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R., & Smith, T. (2024). Active noise cancellation in internal combustion engines using adaptive feedforward control. Applied Acoustics, 215, 109742. [CrossRef]

- González Alice Elizabeth, Cataldo Ottieri, José; Gianoli Kovar, Pablo; Montero Croucciée, Joaquín; Lisboa Marcos Raúl (2017). Measuring sound pressure levels during thermoacoustic instabilities in large engines: case study. Journal of Modern Physics, SCIRP, 2017.

- Schuermans, Bruno (2003) Modeling and control of thermoacoustic instabilities. Ph. D. Thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, 2003.

- UNE-EN-ISO 3744:2010 Standard Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación - Comité Europeo de Normalización. Norma UNE-EN-ISO 3744:2010. Acústica: Determinación de los niveles de potencia acústica y de los niveles de energía acústica de fuentes de ruido utilizando presión acústica. Métodos de ingeniería para un campo esencialmente libre sobre un plano reflectante (ISO 3744:2010). 84 pp. Julio, 2011.

- Vineeth Nair; Gireehkumaran Thampi; Sulochana Karuppusamy; Saravanan Gopalan; R. I. Sujith (2013) Loss of chaos in combustion noise as a precursor of impending combustion instability. International journal of spray and combustion dynamics, v. 5, N. 4, 2013, pp. 273–290.).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).