Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

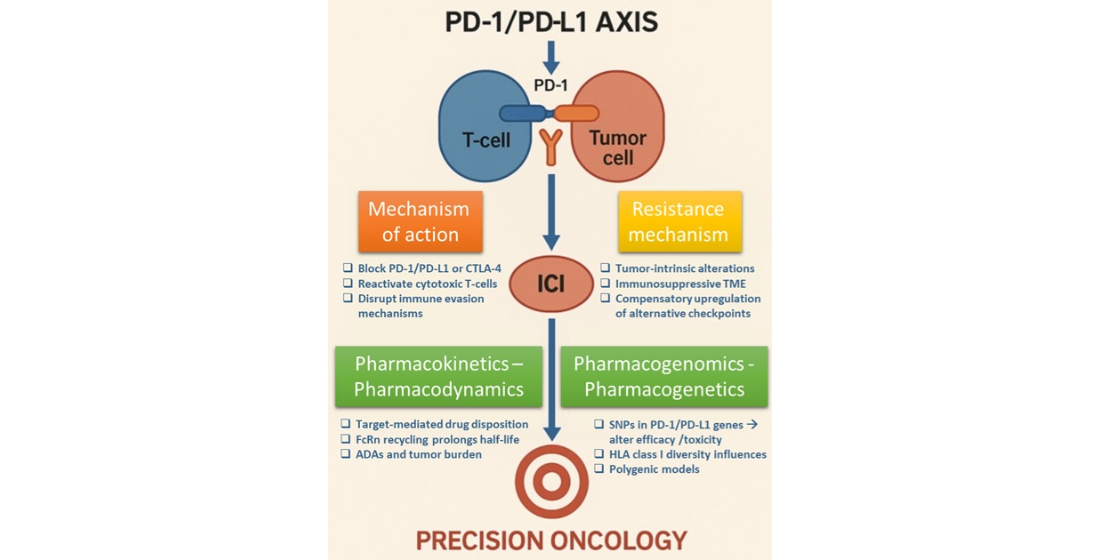

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

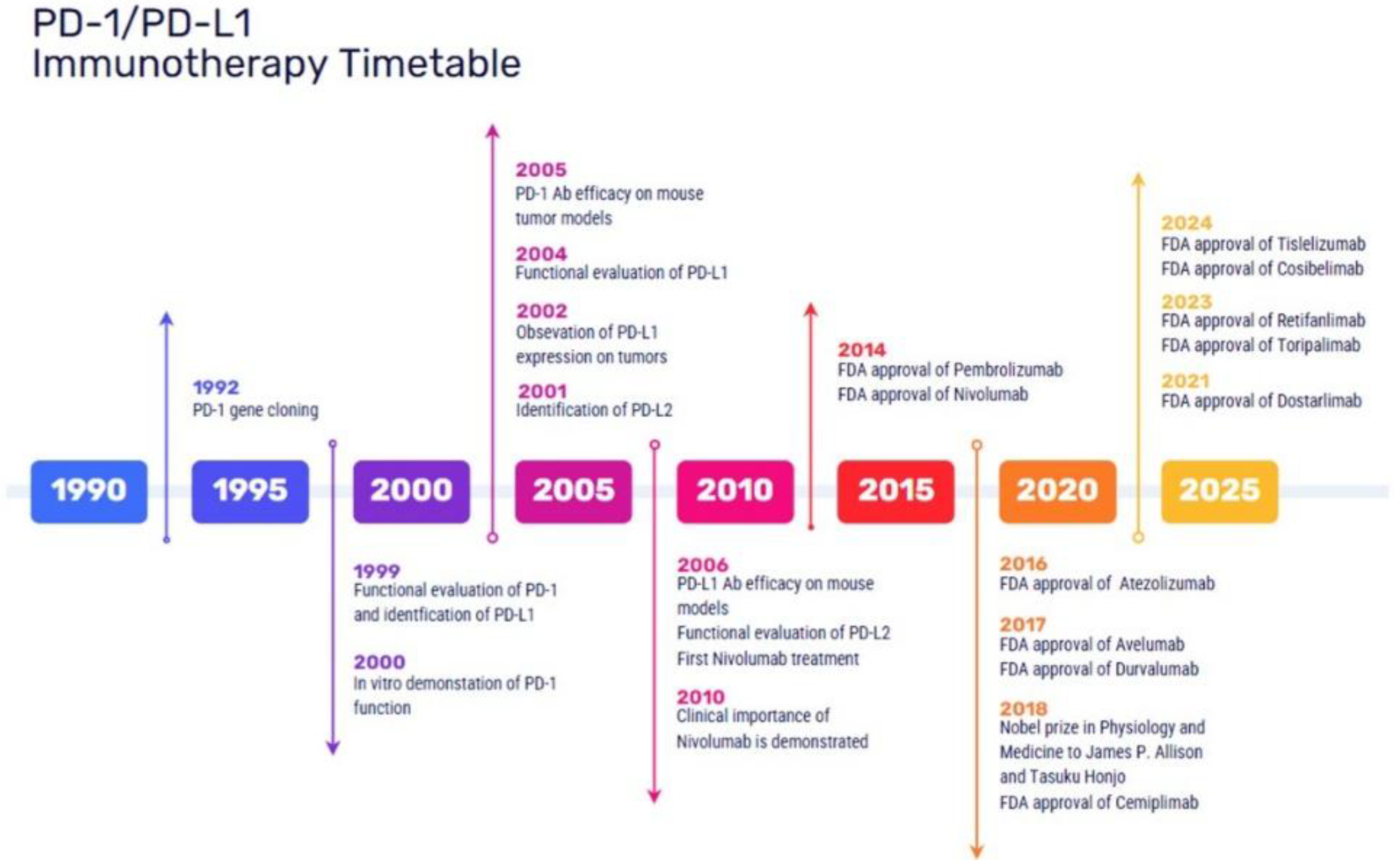

2. Evolution of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment

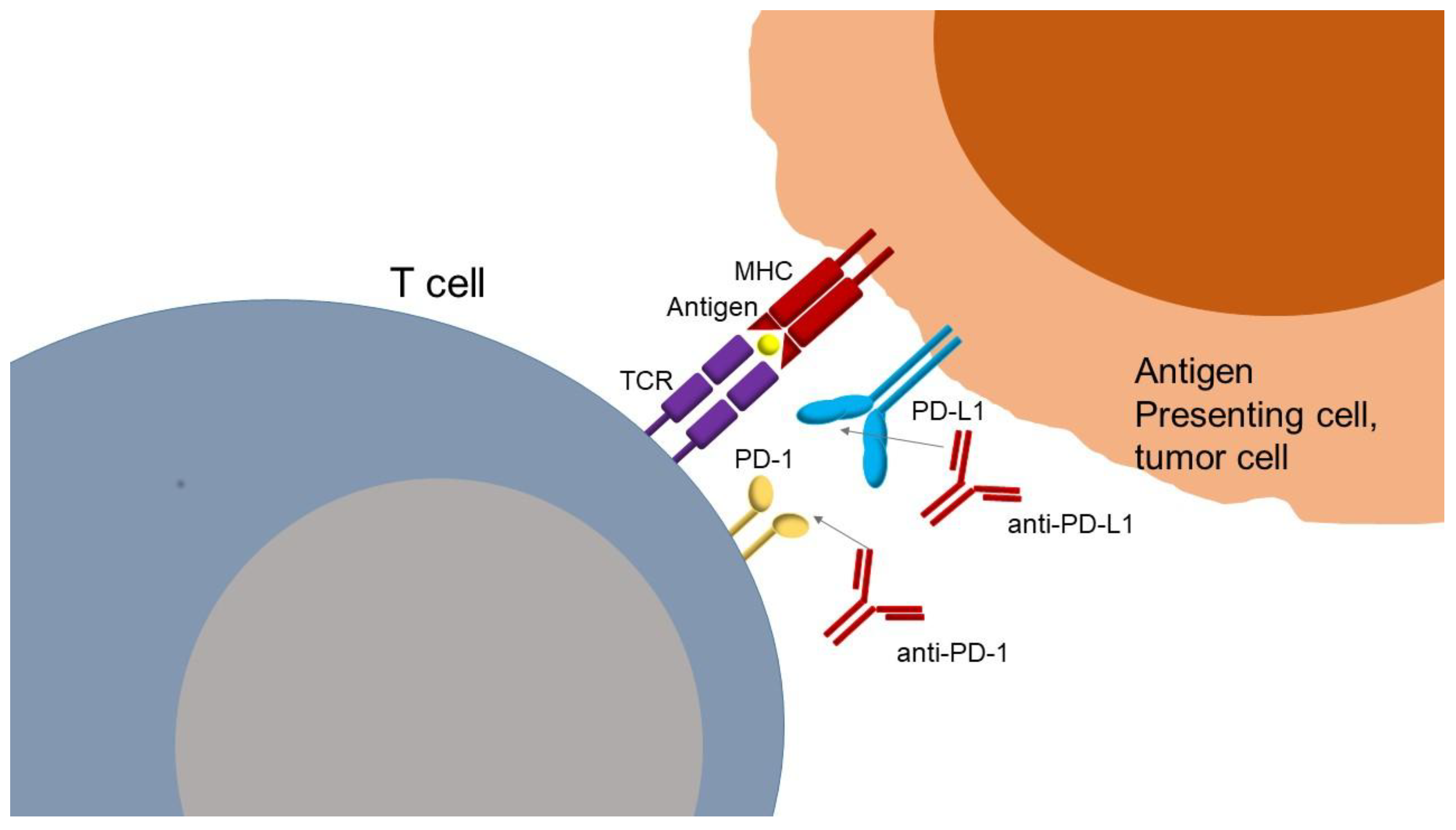

3. Mechanisms of ICIs Action

4. The Role of ICIs in the Treatment of Solid Tumors

1. Skin Cancers

2. Lung Cancer

3. Gastrointestinal Malignancies

4. Breast Cancer

5. Gynaecological Malignancies

5. Genitourinary Malignancies

6. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas (HNSCC)

7. Haematological Malignancies

5. ICIs Pharmacokinetics - Pharmacodynamics

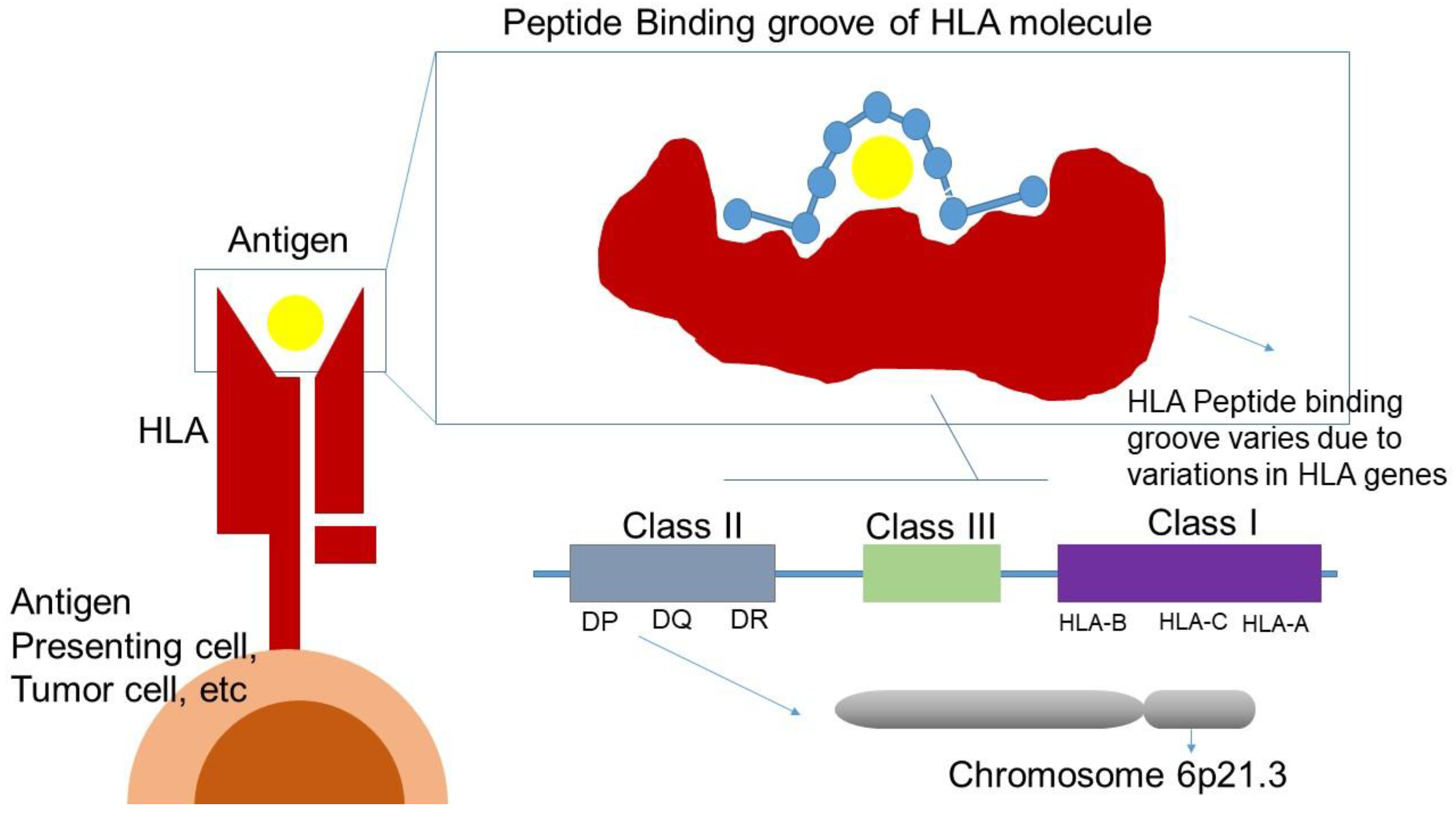

6. Pharmacogenomics -Pharmacogenetics

| Generic name | Dose range (mg/kg ) | t½ (days) | CL (L/day) | Vc (L) | Vp (L) | Q (L/day) | IIV (CV%) | Ref. |

| Atezolizumab | 1–20 | 27 | 0.20 | 3.28 | 3.63 | 0.546 | CL: 29%,Vc: 18%, Vp: 34% | [107] |

| Avelumab | 1–20 | 6,1 | 0.59 | 2.83 | 1.17 | CL: 25.2%, Vc: 18.3%, Vp: 1.05% | * | |

| Durvalumab | 0.1–20 | 21 | 0.232 | 3.51 | 3.45 | 0.476 | CL: 27.2%, Vc: 22.1% | ** |

| Nivolumab | 0.1–20 | 25 | 0.23 | 3.63 | 2.78 | 0.770 | CL: 35%, Vc: 35.1% | [108] |

| Pembrolizumab | 1–10 | 27,3 | 0.22 | 3.48 | 4.06 | 0.795 | CL: 38%,Vc: 21% | [109] |

| Cemiplimab | 1–10 | 28,9 | 0.290 | 3.32 | 1.65 | 0.638 | CL, Q: 8.70% | [110] |

| Dostarlimab | 500 mg or 1000 mg | 23,5 | 0.179 | 2.98 | 2.10 | 0.547 | CL: 23.5%, Vc: 16.1% | [111] |

| Tislelizumab | 0.5-10 | 23.8 | 0.15 | 3.05 | 1.27 | 0.74 | CL:26.3%, Vc:16.7%, Vp:74.7% | [112] |

| Retifanlimab | 1–10 | 18.7 | 0.2928 | 3.76 | 2.64 | 0.684 | CL: 31.4%, Vc:17.9%, Vp:35.5% | *** |

| Toripalimab | 0.3 -10 | 10 ± 1,5 | 0.3576 | 3.7 | … | …. | …. | **** |

| Camrelizumab | 1–10 | 3–11 | 0.231 | 3.07 | 2.90 | 0.414 | CLline: 50.8%, Vc: 49.5% | [113] |

| Cosibelimab | 800 mg or 1200 mg | 17,4 | 0.238 | 3.58 | 2.31 | … | CL: 30.8% ,Vc: 16.8%, Vp: 53.0% | ***** |

SNPs Within the PD-1 Pathway

SNPs Within the PD-L1 Receptor Gene

HLA and Response to ICI Treatment

7. Drug Resistance

Tumor Antigen Deletion

T Cell Dysfunction

Increase in Immunosuppressive Cells

Drug Resistance due to Changes in PD-L1 Expression

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Drug Resistance

i. Histone Deacetylases (HDACs)

ii. Histone Methyltransferases (HMT/EZH2)

iii. miRNAs in Cancers and in Resistance to ICIs

iv. Alteration of Tumor Immunogenicity

v. DNA Methylation and Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Treatment Resistance

Further Difficulties of ICIs Treatments

8. Biomarkers Participating in the Immune Inhibition Process

Checkpoints

Immune-Activation Mechanism

Immune Inhibitory Mechanisms

Potential Biomarkers

i. Biomarkers Related to DNA Damage/Antigen Presentation/Interferon Signaling

ii. Tumor-Infiltrated T Cells (TILs)

iii. Peripheral T Cells

Gut Microbiome

Other Immune Check Points

Other Potential Peripheral Blood Biomarkers

9. Biomarkers in ICI Treatments in Clinical Practice

PD-L1 Expression

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

MSI-H/dMMR

Cost Effectiveness of Biomarkers

10. Discussion

Prospectives – Novel Therapies – Precision Medicine

Promising Ongoing Clinical Trials

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Shan, Q.; Liang, T.; Forde, P.; Zheng, L. Clinical development of immuno-oncology therapeutics. Cancer letters 2025, 617, 217616. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2015, 348, 56-61. [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Cancer 2012, 12, 252-264. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Agata, Y.; Shibahara, K.; Honjo, T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. The EMBO journal 1992, 11, 3887-3895. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, G.J.; Long, A.J.; Iwai, Y.; Bourque, K.; Chernova, T.; Nishimura, H.; Fitz, L.J.; Malenkovich, N.; Okazaki, T.; Byrne, M.C.; et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. The Journal of experimental medicine 2000, 192, 1027-1034. [CrossRef]

- Latchman, Y.; Wood, C.R.; Chernova, T.; Chaudhary, D.; Borde, M.; Chernova, I.; Iwai, Y.; Long, A.J.; Brown, J.A.; Nunes, R.; et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nature immunology 2001, 2, 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, F.; Kaneko, K.; Tamura, H.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Ichikawa, M.; Rietz, C.; Flies, D.B.; Lau, J.S.; Zhu, G.; et al. Blockade of B7-H1 and PD-1 by monoclonal antibodies potentiates cancer therapeutic immunity. Cancer research 2005, 65, 1089-1096.

- Brahmer, J.R.; Drake, C.G.; Wollner, I.; Powderly, J.D.; Picus, J.; Sharfman, W.H.; Stankevich, E.; Pons, A.; Salay, T.M.; McMiller, T.L.; et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2010, 28, 3167-3175. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, M.J.; Teng, M.W. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clinical & translational immunology 2018, 7, e1041. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.H. Costimulation of T lymphocytes: the role of CD28, CTLA-4, and B7/BB1 in interleukin-2 production and immunotherapy. Cell 1992, 71, 1065-1068. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Powles, T.; van der Heijden, M.S.; Balar, A.V.; Necchi, A.; Dawson, N.; O'Donnell, P.H.; Balmanoukian, A.; Loriot, Y.; et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2016, 387, 1909-1920. [CrossRef]

- Massard, C.; Gordon, M.S.; Sharma, S.; Rafii, S.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Luke, J.; Curiel, T.J.; Colon-Otero, G.; Hamid, O.; Sanborn, R.E.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Durvalumab (MEDI4736), an Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2016, 34, 3119-3125. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Russell, J.; Hamid, O.; Bhatia, S.; Terheyden, P.; D'Angelo, S.P.; Shih, K.C.; Lebbé, C.; Linette, G.P.; Milella, M.; et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2016, 17, 1374-1385. [CrossRef]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Chung, C.H.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Lim, A.M.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 379, 341-351. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Dunmall, L.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Fan, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y. The dilemmas and possible solutions for CAR-T cell therapy application in solid tumors. Cancer letters 2024, 591, 216871. [CrossRef]

- Al Hadidi, S.; Heslop, H.E.; Brenner, M.K.; Suzuki, M. Bispecific antibodies and autologous chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies for treatment of hematological malignancies. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2024, 32, 2444-2460. [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Lin, Y.; Mai, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Cui, L. Targeting cancer with precision: strategical insights into TCR-engineered T cell therapies. Theranostics 2025, 15, 300-323. [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Rodas, M.; Villalba-Esparza, M.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Chen, L.; Rimm, D.L.; Schalper, K.A. Biological and clinical significance of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in the era of immunotherapy: a multidimensional approach. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 2025, 22, 163-181. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, M.; Ren, F.; Meng, X.; Yu, J. The landscape of bispecific T cell engager in cancer treatment. Biomarker research 2021, 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Bispecific T cell engagers: an emerging therapy for management of hematologic malignancies. Journal of hematology & oncology 2021, 14, 75. [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, W.; Dong, C. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: advancements, challenges, and prospects. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8, 450. [CrossRef]

- Bommareddy, P.K.; Shettigar, M.; Kaufman, H.L. Integrating oncolytic viruses in combination cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology 2018, 18, 498-513. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology 2004, 4, 336-347. [CrossRef]

- Intlekofer, A.M.; Thompson, C.B. At the bench: preclinical rationale for CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade as cancer immunotherapy. Journal of leukocyte biology 2013, 94, 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Boussiotis, V.A. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. The New England journal of medicine 2016, 375, 1767-1778. [CrossRef]

- Lázár-Molnár, E.; Yan, Q.; Cao, E.; Ramagopal, U.; Nathenson, S.G.; Almo, S.C. Crystal structure of the complex between programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 10483-10488. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, A.H.; Pauken, K.E. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nature reviews. Immunology 2018, 18, 153-167. [CrossRef]

- Laderach, D.; Movassagh, M.; Johnson, A.; Mittler, R.S.; Galy, A. 4-1BB co-stimulation enhances human CD8(+) T cell priming by augmenting the proliferation and survival of effector CD8(+) T cells. International immunology 2002, 14, 1155-1167. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Cui, J.J.; Zhan, Y.; Ouyang, Q.Y.; Lu, Q.S.; Yang, D.H.; Li, X.P.; Yin, J.Y. Reprogramming the tumor microenvironment by genome editing for precision cancer therapy. Molecular cancer 2022, 21, 98. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, D.M.; Do, M.H.; Phillips, G.S.; Postow, M.A.; Akaike, T.; Nghiem, P.; Lacouture, M.E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2020, 83, 1239-1253. [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Chesney, J.; Pavlick, A.C.; Robert, C.; Grossmann, K.F.; McDermott, D.F.; Linette, G.P.; Meyer, N.; Giguere, J.K.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2016, 17, 1558-1568. [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Lucas, M.W.; Scolyer, R.A.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Lopez-Yurda, M.; Hoeijmakers, L.L.; Saw, R.P.M.; Lijnsvelt, J.M.; Maher, N.G.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Resectable Stage III Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine 2024, 391, 1696-1708. [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Del Vecchio, M.; Mandalá, M.; Gogas, H.; Arance Fernandez, A.M.; Dalle, S.; Cowey, C.L.; Schenker, M.; Grob, J.J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III/IV Melanoma: 5-Year Efficacy and Biomarker Results from CheckMate 238. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2023, 29, 3352-3361. [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Khattak, M.A.; Rutkowski, P.; Del Vecchio, M.; Spagnolo, F.; Mackiewicz, J.; Merino, L.C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Kirkwood, J.M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma: Long-term follow-up, crossover, and rechallenge with pembrolizumab in the phase III KEYNOTE-716 study. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2025, 220, 115381. [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, P.; Bhatia, S.; Lipson, E.J.; Sharfman, W.H.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; Brohl, A.S.; Friedlander, P.A.; Daud, A.; Kluger, H.M.; Reddy, S.A.; et al. Durable Tumor Regression and Overall Survival in Patients With Advanced Merkel Cell Carcinoma Receiving Pembrolizumab as First-Line Therapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 693-702. [CrossRef]

- Damsin, T.; Lebas, E.; Marchal, N.; Rorive, A.; Nikkels, A.F. Cemiplimab for locally advanced and metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Expert review of anticancer therapy 2022, 22, 243-248. [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Schmalbach, C.E. Updates in the Management of Advanced Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Surgical oncology clinics of North America 2024, 33, 723-733. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Cosibelimab: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 695-698. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.A.; Weiss, J. Advances in the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Immunotherapy. Clinics in chest medicine 2020, 41, 237-247. [CrossRef]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; Leighl, N.; Balmanoukian, A.S.; Eder, J.P.; Patnaik, A.; Aggarwal, C.; Gubens, M.; Horn, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2015, 372, 2018-2028. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. The New England journal of medicine 2020, 383, 1328-1339. [CrossRef]

- Sezer, A.; Kilickap, S.; Gümüş, M.; Bondarenko, I.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Gogishvili, M.; Turk, H.M.; Cicin, I.; Bentsion, D.; Gladkov, O.; et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 397, 592-604. [CrossRef]

- Landre, T.; Justeau, G.; Assié, J.B.; Chouahnia, K.; Davoine, C.; Taleb, C.; Chouaïd, C.; Duchemann, B. Anti-PD-(L)1 for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancers: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2022, 71, 719-726. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Yu, J. The Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors vs. Chemotherapy for KRAS-Mutant or EGFR-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancers: A Meta-Analysis Based on Randomized Controlled Trials. Disease markers 2022, 2022, 2631852. [CrossRef]

- Cascone, T.; Awad, M.M.; Spicer, J.D.; He, J.; Lu, S.; Sepesi, B.; Tanaka, F.; Taube, J.M.; Cornelissen, R.; Havel, L.; et al. Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2024, 390, 1756-1769. [CrossRef]

- Wakelee, H.; Liberman, M.; Kato, T.; Tsuboi, M.; Lee, S.H.; Gao, S.; Chen, K.N.; Dooms, C.; Majem, M.; Eigendorff, E.; et al. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2023, 389, 491-503. [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe Caro, R.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S.W.; Carcereny Costa, E.; Park, K.; Alexandru, A.; Lupinacci, L.; de la Mora Jimenez, E.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2019, 381, 2020-2031. [CrossRef]

- West, H.; McCleod, M.; Hussein, M.; Morabito, A.; Rittmeyer, A.; Conter, H.J.; Kopp, H.G.; Daniel, D.; McCune, S.; Mekhail, T.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2019, 20, 924-937. [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Kurata, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; de Wit, M.; et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 379, 2342-2350. [CrossRef]

- Heymach, J.V.; Harpole, D.; Mitsudomi, T.; Taube, J.M.; Galffy, G.; Hochmair, M.; Winder, T.; Zukov, R.; Garbaos, G.; Gao, S.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2023, 389, 1672-1684. [CrossRef]

- Felip, E.; Altorki, N.; Zhou, C.; Csőszi, T.; Vynnychenko, I.; Goloborodko, O.; Luft, A.; Akopov, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Kenmotsu, H.; et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 398, 1344-1357. [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.; Mansfield, A.S.; Szczęsna, A.; Havel, L.; Krzakowski, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Huemer, F.; Losonczy, G.; Johnson, M.L.; Nishio, M.; et al. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 379, 2220-2229. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.W.; Dvorkin, M.; Chen, Y.; Reinmuth, N.; Hotta, K.; Trukhin, D.; Statsenko, G.; Hochmair, M.J.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Ji, J.H.; et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2021, 22, 51-65. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Spigel, D.R.; Cho, B.C.; Laktionov, K.K.; Fang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zenke, Y.; Lee, K.H.; Wang, Q.; Navarro, A.; et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Limited-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2024, 391, 1313-1327. [CrossRef]

- Janjigian, Y.Y.; Shitara, K.; Moehler, M.; Garrido, M.; Salman, P.; Shen, L.; Wyrwicz, L.; Yamaguchi, K.; Skoczylas, T.; Campos Bragagnoli, A.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2021, 398, 27-40. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.; Kojima, T.; Hochhauser, D.; Enzinger, P.; Raimbourg, J.; Hollebecque, A.; Lordick, F.; Kim, S.B.; Tajika, M.; Kim, H.T.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab for Heavily Pretreated Patients With Advanced, Metastatic Adenocarcinoma or Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus: The Phase 2 KEYNOTE-180 Study. JAMA oncology 2019, 5, 546-550. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.J.; Ajani, J.A.; Kuzdzal, J.; Zander, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Piessen, G.; Mendez, G.; Feliciano, J.; Motoyama, S.; Lièvre, A.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 384, 1191-1203. [CrossRef]

- Rha, S.Y.; Oh, D.Y.; Yañez, P.; Bai, Y.; Ryu, M.H.; Lee, J.; Rivera, F.; Alves, G.V.; Garrido, M.; Shiu, K.K.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer (KEYNOTE-859): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2023, 24, 1181-1195. [CrossRef]

- Janjigian, Y.Y.; Kawazoe, A.; Bai, Y.; Xu, J.; Lonardi, S.; Metges, J.P.; Yanez, P.; Wyrwicz, L.S.; Shen, L.; Ostapenko, Y.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy for HER2-positive gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: interim analyses from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-811 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2023, 402, 2197-2208. [CrossRef]

- Grieb, B.C.; Agarwal, R. HER2-Directed Therapy in Advanced Gastric and Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma: Triumphs and Troubles. Current treatment options in oncology 2021, 22, 88. [CrossRef]

- Moehler, M.; Oh, D.Y.; Kato, K.; Arkenau, T.; Tabernero, J.; Lee, K.W.; Rha, S.Y.; Hirano, H.; Spigel, D.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. First-Line Tislelizumab Plus Chemotherapy for Advanced Gastric Cancer with Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression ≥ 1%: A Retrospective Analysis of RATIONALE-305. Advances in therapy 2025, 42, 2248-2268. [CrossRef]

- Yoshinami, Y.; Shoji, H. Recent advances in immunotherapy and molecular targeted therapy for gastric cancer. Future science OA 2023, 9, Fso842. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Stadler, Z.K.; Cercek, A.; Mendelsohn, R.B.; Shia, J.; Segal, N.H.; Diaz, L.A., Jr. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology 2019, 16, 361-375. [CrossRef]

- Overman, M.J.; McDermott, R.; Leach, J.L.; Lonardi, S.; Lenz, H.J.; Morse, M.A.; Desai, J.; Hill, A.; Axelson, M.; Moss, R.A.; et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. The Lancet. Oncology 2017, 18, 1182-1191. [CrossRef]

- Chalabi, M.; Verschoor, Y.L.; Tan, P.B.; Balduzzi, S.; Van Lent, A.U.; Grootscholten, C.; Dokter, S.; Büller, N.V.; Grotenhuis, B.A.; Kuhlmann, K.; et al. Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Locally Advanced Mismatch Repair-Deficient Colon Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2024, 390, 1949-1958. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Edeline, J.; Cattan, S.; Ogasawara, S.; Palmer, D.; Verslype, C.; Zagonel, V.; Fartoux, L.; Vogel, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2018, 19, 940-952. [CrossRef]

- El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Sangro, B.; Yau, T.; Crocenzi, T.S.; Kudo, M.; Hsu, C.; Kim, T.Y.; Choo, S.P.; Trojan, J.; Welling, T.H.R.; et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet (London, England) 2017, 389, 2492-2502. [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2020, 382, 1894-1905. [CrossRef]

- Sangro, B.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Yarchoan, M.; De Toni, E.N.; Furuse, J.; Kang, Y.K.; et al. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2024, 35, 448-457. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Chan, S.L.; Gu, S.; Bai, Y.; Ren, Z.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Jia, W.; Jin, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): a randomised, open-label, international phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England) 2023, 402, 1133-1146. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.S.; Adams, S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Henschel, V.; Molinero, L.; Chui, S.Y.; et al. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion130): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2020, 21, 44-59. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, B.; Gumusay, O. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2020, 382, e108. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, N.; Dubot, C.; Lorusso, D.; Caceres, M.V.; Hasegawa, K.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Tewari, K.S.; Salman, P.; Hoyos Usta, E.; Yañez, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Persistent, Recurrent, or Metastatic Cervical Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 385, 1856-1867. [CrossRef]

- Oaknin, A.; Tinker, A.V.; Gilbert, L.; Samouëlian, V.; Mathews, C.; Brown, J.; Barretina-Ginesta, M.P.; Moreno, V.; Gravina, A.; Abdeddaim, C.; et al. Clinical Activity and Safety of the Anti-Programmed Death 1 Monoclonal Antibody Dostarlimab for Patients With Recurrent or Advanced Mismatch Repair-Deficient Endometrial Cancer: A Nonrandomized Phase 1 Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology 2020, 6, 1766-1772. [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.A.; Cibula, D.; O'Malley, D.M.; Boere, I.; Shahin, M.S.; Savarese, A.; Chase, D.M.; Gilbert, L.; Black, D.; Herrstedt, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dostarlimab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with dMMR/MSI-H primary advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer in a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ENGOT-EN6-NSGO/GOG-3031/RUBY). Gynecologic oncology 2025, 192, 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Di Dio, C.; Bogani, G.; Di Donato, V.; Cuccu, I.; Muzii, L.; Musacchio, L.; Scambia, G.; Lorusso, D. The role of immunotherapy in advanced and recurrent MMR deficient and proficient endometrial carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology 2023, 169, 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Westin, S.N.; Moore, K.; Chon, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Thomes Pepin, J.; Sundborg, M.; Shai, A.; de la Garza, J.; Nishio, S.; Gold, M.A.; et al. Durvalumab Plus Carboplatin/Paclitaxel Followed by Maintenance Durvalumab With or Without Olaparib as First-Line Treatment for Advanced Endometrial Cancer: The Phase III DUO-E Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, 283-299. [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Arén Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, 1277-1290. [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2019, 380, 1116-1127. [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Penkov, K.; Haanen, J.; Rini, B.; Albiges, L.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Negrier, S.; Uemura, M.; et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2019, 380, 1103-1115. [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Zurawski, B.; Oyervides Juárez, V.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Basso, U.; Shah, A.Y.; et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 384, 829-841. [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Kopyltsov, E.; Méndez-Vidal, M.J.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2021, 384, 1289-1300. [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Csőszi, T.; Özgüroğlu, M.; Matsubara, N.; Géczi, L.; Cheng, S.Y.; Fradet, Y.; Oudard, S.; Vulsteke, C.; Morales Barrera, R.; et al. Pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (KEYNOTE-361): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2021, 22, 931-945. [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2020, 383, 1218-1230. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M.; Sade, J.P.; Bamias, A.; Beuzeboc, P.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus Gemcitabine-Cisplatin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 2023, 389, 1778-1789. [CrossRef]

- Oridate, N.; Takahashi, S.; Tanaka, K.; Shimizu, Y.; Fujimoto, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Yokota, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Takahashi, M.; Ueda, T.; et al. First-line pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: 5-year follow-up of the Japanese population of KEYNOTE-048. International journal of clinical oncology 2024, 29, 1825-1839. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.L.; Liu, X.; Shen, L.F.; Hu, G.Y.; Zou, G.R.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.B.; Chen, X.Z.; Zhu, X.D.; Yuan, Y.W.; et al. Adjuvant PD-1 Blockade With Camrelizumab for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: The DIPPER Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, D.; Xu, X.; Xiao, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W. A real-world evaluation of tislelizumab in patients with head and neck cancer. Translational cancer research 2024, 13, 808-818. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Li, X.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Wen, D.X.; Guo, S.S.; Liu, L.T.; Li, Y.F.; Luo, M.J.; Xie, S.Y.; Liang, Y.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant toripalimab for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a randomised, single-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2024, 25, 1563-1575. [CrossRef]

- Younes, A.; Santoro, A.; Shipp, M.; Zinzani, P.L.; Timmerman, J.M.; Ansell, S.; Armand, P.; Fanale, M.; Ratanatharathorn, V.; Kuruvilla, J.; et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin's lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. The Lancet. Oncology 2016, 17, 1283-1294. [CrossRef]

- Armand, P.; Rodig, S.; Melnichenko, V.; Thieblemont, C.; Bouabdallah, K.; Tumyan, G.; Özcan, M.; Portino, S.; Fogliatto, L.; Caballero, M.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Relapsed or Refractory Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2019, 37, 3291-3299. [CrossRef]

- Centanni, M.; Moes, D.; Trocóniz, I.F.; Ciccolini, J.; van Hasselt, J.G.C. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2019, 58, 835-857. [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yu, L.; Shangguan, D.; Li, W.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Tang, J.; Liao, D. Advances in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. International immunopharmacology 2023, 115, 109638. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, U.J.; Socher, I.; Braeunlich, C.G.; Kroll, H.; Bein, G.; Santoso, S. A variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism influences the transcriptional activity of the neonatal Fc receptor alpha-chain promoter. Immunology 2006, 119, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Keizer, R.J.; Huitema, A.D.; Schellens, J.H.; Beijnen, J.H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2010, 49, 493-507. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, E.Q.; Balthasar, J.P. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2008, 84, 548-558. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Suryawanshi, S.; Hruska, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Vezina, H.E.; McHenry, M.B.; Waxman, I.M.; Achanta, A.; et al. Assessment of nivolumab benefit-risk profile of a 240-mg flat dose relative to a 3-mg/kg dosing regimen in patients with advanced tumors. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2017, 28, 2002-2008. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Song, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.; Xu, J.; Maher, V.E.; et al. Association of time-varying clearance of nivolumab with disease dynamics and its implications on exposure response analysis. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2017, 101, 657-666. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Subramaniam, S.; Zhao, H.; Blumenthal, G.M.; Turner, D.C.; Li, C.; Ahamadi, M.; et al. Time dependent pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab in patients with solid tumor and its correlation with best overall response. Journal of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics 2017, 44, 403-414. [CrossRef]

- Porporato, P.E. Understanding cachexia as a cancer metabolism syndrome. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e200. [CrossRef]

- Baverel, P.G.; Dubois, V.F.S.; Jin, C.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Song, X.; Jin, X.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Gupta, A.; Dennis, P.A.; Ben, Y.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Durvalumab in Cancer Patients and Association With Longitudinal Biomarkers of Disease Status. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2018, 103, 631-642. [CrossRef]

- Beers, S.A.; Glennie, M.J.; White, A.L. Influence of immunoglobulin isotype on therapeutic antibody function. Blood 2016, 127, 1097-1101. [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, A.; Schwanbeck, R.; Valerius, T.; Rösner, T. Antibody Isotypes for Tumor Immunotherapy. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie 2017, 44, 320-326. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Subudhi, S.K.; Blando, J.; Scutti, J.; Vence, L.; Wargo, J.; Allison, J.P.; Ribas, A.; Sharma, P. Anti-CTLA-4 Immunotherapy Does Not Deplete FOXP3(+) Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) in Human Cancers. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019, 25, 1233-1238. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Feng, Y.; Roy, A.; Kollia, G.; Lestini, B. Nivolumab dose selection: challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned for cancer immunotherapy. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2016, 4, 72. [CrossRef]

- Oude Munnink, T.H.; Henstra, M.J.; Segerink, L.I.; Movig, K.L.; Brummelhuis-Visser, P. Therapeutic drug monitoring of monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory and malignant disease: Translating TNF-α experience to oncology. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2016, 99, 419-431. [CrossRef]

- Stroh, M., H. Winter, M. Marchand, L. Claret, S. Eppler, J. Ruppel, O. Abidoye, S. L. Teng, W. T. Lin, S. Dayog, R. Bruno, J. Jin, and S. Girish. "Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Atezolizumab in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma." Clin Pharmacol Ther 102, no. 2 (2017): 305-12.

- Shek, D.; Read, S.A.; Ahlenstiel, G.; Piatkov, I. Pharmacogenetics of anticancer monoclonal antibodies. Cancer drug resistance (Alhambra, Calif.) 2019, 2, 69-81. [CrossRef]

- Michot, J.M.; Bigenwald, C.; Champiat, S.; Collins, M.; Carbonnel, F.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Berdelou, A.; Varga, A.; Bahleda, R.; Hollebecque, A.; et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2016, 54, 139-148. [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Haanen, J.B.; Ribas, A.; Schumacher, T.N. CANCER IMMUNOLOGY. The "cancer immunogram". Science (New York, N.Y.) 2016, 352, 658-660. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Hsu, J.M.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.C.; Hung, M.C. Advances and prospects of biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cell reports. Medicine 2024, 5, 101621. [CrossRef]

- Heersche, N.; Veerman, G.D.M.; de With, M.; Bins, S.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Dingemans, A.C.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Jansman, F.G.A. Clinical implications of germline variations for treatment outcome and drug resistance for small molecule kinase inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Drug resistance updates : reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy 2022, 62, 100832. [CrossRef]

- de Joode, K.; Heersche, N.; Basak, E.A.; Bins, S.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Mathijssen, R.H.J. Review - The impact of pharmacogenetics on the outcome of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer treatment reviews 2024, 122, 102662. [CrossRef]

- Stroh, M.; Winter, H.; Marchand, M.; Claret, L.; Eppler, S.; Ruppel, J.; Abidoye, O.; Teng, S.L.; Lin, W.T.; Dayog, S.; et al. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Atezolizumab in Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2017, 102, 305-312. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, G.; Wang, X.; Agrawal, S.; Gupta, M.; Roy, A.; Feng, Y. Model-Based Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Nivolumab in Patients With Solid Tumors. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2017, 6, 58-66. [CrossRef]

- Ahamadi, M.; Freshwater, T.; Prohn, M.; Li, C.H.; de Alwis, D.P.; de Greef, R.; Elassaiss-Schaap, J.; Kondic, A.; Stone, J.A. Model-Based Characterization of the Pharmacokinetics of Pembrolizumab: A Humanized Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody in Advanced Solid Tumors. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2017, 6, 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Paccaly, A.J.; Rippley, R.K.; Davis, J.D.; DiCioccio, A.T. Population pharmacokinetic characteristics of cemiplimab in patients with advanced malignancies. Journal of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics 2021, 48, 479-494. [CrossRef]

- Melhem, M.; Hanze, E.; Lu, S.; Alskär, O.; Visser, S.; Gandhi, Y. Population pharmacokinetics and exposure-response of anti-programmed cell death protein-1 monoclonal antibody dostarlimab in advanced solid tumours. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2022, 88, 4142-4154. [CrossRef]

- Budha, N.; Wu, C.Y.; Tang, Z.; Yu, T.; Liu, L.; Xu, F.; Gao, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, Y.; et al. Model-based population pharmacokinetic analysis of tislelizumab in patients with advanced tumors. CPT: pharmacometrics & systems pharmacology 2023, 12, 95-109. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Sheng, C.C.; Ma, G.L.; Xu, D.; Liu, X.Q.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, C.L.; Xu, B.H.; Song, Y.Q.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of the anti-PD-1 antibody camrelizumab in patients with multiple tumor types and model-informed dosing strategy. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 1368-1375. [CrossRef]

- Groha, S.; Alaiwi, S.A.; Xu, W.; Naranbhai, V.; Nassar, A.H.; Bakouny, Z.; El Zarif, T.; Saliby, R.M.; Wan, G.; Rajeh, A.; et al. Germline variants associated with toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 2584-2591. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, N.; Diab, A.; Yu, R.K.; Futreal, A.; Criswell, L.A.; Tayar, J.H.; Dadu, R.; Shannon, V.; Shete, S.S.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. Genetic determinants of immune-related adverse events in patients with melanoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2021, 70, 1939-1949. [CrossRef]

- Montaudié, H.; Beranger, G.E.; Reinier, F.; Nottet, N.; Martin, H.; Picard-Gauci, A.; Troin, L.; Ballotti, R.; Passeron, T. Germline variants in exonic regions have limited impact on immune checkpoint blockade clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Pigment cell & melanoma research 2021, 34, 978-983. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Watson, R.A.; Tong, O.; Ye, W.; Nassiri, I.; Gilchrist, J.J.; de Los Aires, A.V.; Sharma, P.K.; Koturan, S.; Cooper, R.A.; et al. IL7 genetic variation and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with melanoma. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 2592-2600. [CrossRef]

- Parakh, S.; Musafer, A.; Paessler, S.; Witkowski, T.; Suen, C.; Tutuka, C.S.A.; Carlino, M.S.; Menzies, A.M.; Scolyer, R.A.; Cebon, J.; et al. PDCD1 Polymorphisms May Predict Response to Anti-PD-1 Blockade in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 672521. [CrossRef]

- Refae, S.; Gal, J.; Ebran, N.; Otto, J.; Borchiellini, D.; Peyrade, F.; Chamorey, E.; Brest, P.; Milano, G.; Saada-Bouzid, E. Germinal Immunogenetics predict treatment outcome for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. Investigational new drugs 2020, 38, 160-171. [CrossRef]

- de With, M.; Hurkmans, D.P.; Oomen-de Hoop, E.; Lalouti, A.; Bins, S.; El Bouazzaoui, S.; van Brakel, M.; Debets, R.; Aerts, J.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; et al. Germline Variation in PDCD1 Is Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Treated with Anti-PD-1 Monotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Numakura, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; Muto, Y.; Sekine, Y.; Sasagawa, H.; Kashima, S.; Yamamoto, R.; Koizumi, A.; Nara, T.; et al. Severe Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Nivolumab for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Are Associated with PDCD1 Polymorphism. Genes 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Suminaga, K.; Nomizo, T.; Yoshida, H.; Ozasa, H. The impact of PD-L1 polymorphisms on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors depends on the tumor proportion score: a retrospective study. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 2025, 151, 61. [CrossRef]

- Nomizo, T.; Ozasa, H.; Tsuji, T.; Funazo, T.; Yasuda, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Yagi, Y.; Sakamori, Y.; Nagai, H.; Hirai, T.; et al. Clinical Impact of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in PD-L1 on Response to Nivolumab for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 45124. [CrossRef]

- Del Re, M.; Cucchiara, F.; Rofi, E.; Fontanelli, L.; Petrini, I.; Gri, N.; Pasquini, G.; Rizzo, M.; Gabelloni, M.; Belluomini, L.; et al. A multiparametric approach to improve the prediction of response to immunotherapy in patients with metastatic NSCLC. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2021, 70, 1667-1678. [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.; Miyake, H.; Takahashi, M.; Oya, M.; Tsuchiya, N.; Masumori, N.; Matsuyama, H.; Obara, W.; Shinohara, N.; Fujimoto, K.; et al. Effect of genetic polymorphisms on outcomes following nivolumab for advanced renal cell carcinoma in the SNiP-RCC trial. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2023, 72, 1903-1915. [CrossRef]

- Funazo, T.Y.; Nomizo, T.; Ozasa, H.; Tsuji, T.; Yasuda, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Sakamori, Y.; Nagai, H.; Hirai, T.; Kim, Y.H. Clinical impact of low serum free T4 in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 17085. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Nomizo, T.; Ozasa, H.; Tsuji, T.; Funazo, T.; Yasuda, Y.; Ajimizu, H.; Yamazoe, M.; Kuninaga, K.; Ogimoto, T.; et al. PD-L1 polymorphisms predict survival outcomes in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with PD-1 blockade. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2021, 144, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Polcaro, G.; Liguori, L.; Manzo, V.; Chianese, A.; Donadio, G.; Caputo, A.; Scognamiglio, G.; Dell'Annunziata, F.; Langella, M.; Corbi, G.; et al. rs822336 binding to C/EBPβ and NFIC modulates induction of PD-L1 expression and predicts anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in advanced NSCLC. Molecular cancer 2024, 23, 63. [CrossRef]

- Chat, V.; Ferguson, R.; Simpson, D.; Kazlow, E.; Lax, R.; Moran, U.; Pavlick, A.; Frederick, D.; Boland, G.; Sullivan, R.; et al. Autoimmune genetic risk variants as germline biomarkers of response to melanoma immune-checkpoint inhibition. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2019, 68, 897-905. [CrossRef]

- Hurkmans, D.P.; Basak, E.A.; Schepers, N.; Oomen-De Hoop, E.; Van der Leest, C.H.; El Bouazzaoui, S.; Bins, S.; Koolen, S.L.W.; Sleijfer, S.; Van der Veldt, A.A.M.; et al. Granzyme B is correlated with clinical outcome after PD-1 blockade in patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ogimoto, T.; Ozasa, H.; Yoshida, H.; Nomizo, T.; Funazo, T.; Yoshida, H.; Hashimoto, K.; Hosoya, K.; Yamazoe, M.; Ajimizu, H.; et al. CD47 polymorphism for predicting nivolumab benefit in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncology letters 2023, 26, 364. [CrossRef]

- Bins, S.; Basak, E.A.; El Bouazzaoui, S.; Koolen, S.L.W.; Oomen-de Hoop, E.; van der Leest, C.H.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Sleijfer, S.; Debets, R.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; et al. Association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms and adverse events in nivolumab-treated non-small cell lung cancer patients. British journal of cancer 2018, 118, 1296-1301. [CrossRef]

- Haratani, K.; Hayashi, H.; Chiba, Y.; Kudo, K.; Yonesaka, K.; Kato, R.; Kaneda, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Takeda, M.; et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events With Nivolumab Efficacy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA oncology 2018, 4, 374-378. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Jung, D.K.; Choi, J.E.; Jin, C.C.; Hong, M.J.; Do, S.K.; Kang, H.G.; Lee, W.K.; Seok, Y.; Lee, E.B.; et al. Functional polymorphisms in PD-L1 gene are associated with the prognosis of patients with early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Gene 2017, 599, 28-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, F.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.; Li, R.; Liu, C.; Chen, W.; Hua, D.; Zhang, X. A miR-570 binding site polymorphism in the B7-H1 gene is associated with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Human genetics 2013, 132, 641-648. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Jung, D.K.; Choi, J.E.; Jin, C.C.; Hong, M.J.; Do, S.K.; Kang, H.G.; Lee, W.K.; Seok, Y.; Lee, E.B.; et al. PD-L1 polymorphism can predict clinical outcomes of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line paclitaxel-cisplatin chemotherapy. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 25952. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Hammer, C.; Carroll, J.; Di Nucci, F.; Acosta, S.L.; Maiya, V.; Bhangale, T.; Hunkapiller, J.; Mellman, I.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Genetic variation associated with thyroid autoimmunity shapes the systemic immune response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Nature communications 2021, 12, 3355. [CrossRef]

- Postow, M.A.; Sidlow, R.; Hellmann, M.D. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, 158-168. [CrossRef]

- Russo, V.; Klein, T.; Lim, D.J.; Solis, N.; Machado, Y.; Hiroyasu, S.; Nabai, L.; Shen, Y.; Zeglinski, M.R.; Zhao, H.; et al. Granzyme B is elevated in autoimmune blistering diseases and cleaves key anchoring proteins of the dermal-epidermal junction. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 9690. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Martucci, V.L.; Quandt, Z.; Groha, S.; Murray, M.H.; Lovly, C.M.; Rizvi, H.; Egger, J.V.; Plodkowski, A.J.; Abu-Akeel, M.; et al. Immunotherapy-Mediated Thyroid Dysfunction: Genetic Risk and Impact on Outcomes with PD-1 Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2021, 27, 5131-5140. [CrossRef]

- Pierini, F.; Lenz, T.L. Divergent Allele Advantage at Human MHC Genes: Signatures of Past and Ongoing Selection. Molecular biology and evolution 2018, 35, 2145-2158. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Weiskopf, D.; Angelo, M.A.; Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. HLA class I alleles are associated with peptide-binding repertoires of different size, affinity, and immunogenicity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2013, 191, 5831-5839. [CrossRef]

- Cuppens, K.; Baas, P.; Geerdens, E.; Cruys, B.; Froyen, G.; Decoster, L.; Thomeer, M.; Maes, B. HLA-I diversity and tumor mutational burden by comprehensive next-generation sequencing as predictive biomarkers for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with PD-(L)1 inhibitors. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2022, 170, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Chowell, D.; Morris, L.G.T.; Grigg, C.M.; Weber, J.K.; Samstein, R.M.; Makarov, V.; Kuo, F.; Kendall, S.M.; Requena, D.; Riaz, N.; et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2018, 359, 582-587. [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Calapre, L.; Lo, J.; Correia, S.; Bowyer, S.; Chopra, A.; Watson, M.; Khattak, M.A.; Millward, M.; Gray, E.S. Prognostic value of HLA-I homozygosity in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with single agent immunotherapy. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Chhibber, A.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Cristescu, R.; Liu, X.; Mehrotra, D.V.; Shen, J.; Shaw, P.M.; Hellmann, M.D.; et al. Germline HLA landscape does not predict efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy across solid tumor types. Immunity 2022, 55, 56-64.e54. [CrossRef]

- Negrao, M.V.; Lam, V.K.; Reuben, A.; Rubin, M.L.; Landry, L.L.; Roarty, E.B.; Rinsurongkawong, W.; Lewis, J.; Roth, J.A.; Swisher, S.G.; et al. PD-L1 Expression, Tumor Mutational Burden, and Cancer Gene Mutations Are Stronger Predictors of Benefit from Immune Checkpoint Blockade than HLA Class I Genotype in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 2019, 14, 1021-1031. [CrossRef]

- Chowell, D.; Krishna, C.; Pierini, F.; Makarov, V.; Rizvi, N.A.; Kuo, F.; Morris, L.G.T.; Riaz, N.; Lenz, T.L.; Chan, T.A. Evolutionary divergence of HLA class I genotype impacts efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nature medicine 2019, 25, 1715-1720. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; DiNatale, R.G.; Chowell, D.; Krishna, C.; Makarov, V.; Valero, C.; Vuong, L.; Lee, M.; Weiss, K.; Hoen, D.; et al. High Response Rate and Durability Driven by HLA Genetic Diversity in Patients with Kidney Cancer Treated with Lenvatinib and Pembrolizumab. Molecular cancer research : MCR 2021, 19, 1510-1521. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Chen, H.; Jiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Gong, J.; Li, J.; Zou, J.; et al. Germline HLA-B evolutionary divergence influences the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy in gastrointestinal cancer. Genome medicine 2021, 13, 175. [CrossRef]

- Correale, P.; Saladino, R.E.; Giannarelli, D.; Giannicola, R.; Agostino, R.; Staropoli, N.; Strangio, A.; Del Giudice, T.; Nardone, V.; Altomonte, M.; et al. Distinctive germline expression of class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles and DRB1 heterozygosis predict the outcome of patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Naranbhai, V.; Viard, M.; Dean, M.; Groha, S.; Braun, D.A.; Labaki, C.; Shukla, S.A.; Yuki, Y.; Shah, P.; Chin, K.; et al. HLA-A*03 and response to immune checkpoint blockade in cancer: an epidemiological biomarker study. The Lancet. Oncology 2022, 23, 172-184. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Narita, S.; Fujiyama, N.; Hatakeyama, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Kato, R.; Naito, S.; Sakatani, T.; Kashima, S.; Koizumi, A.; et al. Impact of germline HLA genotypes on clinical outcomes in patients with urothelial cancer treated with pembrolizumab. Cancer science 2022, 113, 4059-4069. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Mo, H.; Jiao, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, J. Prognostic and predictive impact of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and HLA-I genotyping in advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy. Thoracic cancer 2022, 13, 1631-1641. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Otsuka, A.; Tanaka, H.; Levesque, M.P.; Dummer, R.; Kabashima, K. HLA-A*26 Is Correlated With Response to Nivolumab in Japanese Melanoma Patients. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2017, 137, 2443-2444. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, L.C.; Dorak, M.T.; Bettinotti, M.P.; Bingham, C.O.; Shah, A.A. Association of HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles and immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced inflammatory arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2019, 58, 476-480. [CrossRef]

- Akturk, H.K.; Couts, K.L.; Baschal, E.E.; Karakus, K.E.; Van Gulick, R.J.; Turner, J.A.; Pyle, L.; Robinson, W.A.; Michels, A.W. Analysis of Human Leukocyte Antigen DR Alleles, Immune-Related Adverse Events, and Survival Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Use Among Patients With Advanced Malignant Melanoma. JAMA network open 2022, 5, e2246400. [CrossRef]

- Hasan Ali, O.; Berner, F.; Bomze, D.; Fässler, M.; Diem, S.; Cozzio, A.; Jörger, M.; Früh, M.; Driessen, C.; Lenz, T.L.; et al. Human leukocyte antigen variation is associated with adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2019, 107, 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Diao, L.; Yang, Y.; Yi, X.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Li, Y.; Villalobos, P.A.; Cascone, T.; Liu, X.; Tan, L.; et al. CD38-Mediated Immunosuppression as a Mechanism of Tumor Cell Escape from PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer discovery 2018, 8, 1156-1175. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhong, M.; Zhong, H.; Ruan, R.; Xiong, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J. Targeting HGF/c-MET signaling to regulate the tumor microenvironment: Implications for counteracting tumor immune evasion. Cell communication and signaling : CCS 2025, 23, 46. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. Regulatory T-cells-related signature for identifying a prognostic subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma with an exhausted tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 975762. [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Helmink, B.A.; Sharma, P.; Wargo, J.A. Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 2021, 184, 5309-5337. [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Rosenthal, R.; Hiley, C.T.; Rowan, A.J.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Wilson, G.A.; Birkbak, N.J.; Veeriah, S.; Van Loo, P.; Herrero, J.; et al. Allele-Specific HLA Loss and Immune Escape in Lung Cancer Evolution. Cell 2017, 171, 1259-1271.e1211. [CrossRef]

- Jhunjhunwala, S.; Hammer, C.; Delamarre, L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nature reviews. Cancer 2021, 21, 298-312. [CrossRef]

- Sade-Feldman, M.; Jiao, Y.J.; Chen, J.H.; Rooney, M.S.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Eliane, J.P.; Bjorgaard, S.L.; Hammond, M.R.; Vitzthum, H.; Blackmon, S.M.; et al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1136. [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Aulakh, L.K.; Lu, S.; Kemberling, H.; Wilt, C.; Luber, B.S.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2017, 357, 409-413. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.Q.; Peng, L.H.; Ma, L.J.; Liu, D.B.; Zhang, S.; Luo, S.Z.; Rao, J.H.; Zhu, H.W.; Yang, S.X.; Xi, S.J.; et al. Heterogeneous immunogenomic features and distinct escape mechanisms in multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology 2020, 72, 896-908. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Nixon, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Castellanos, E.; Estrada, M.V.; Ericsson-Gonzalez, P.I.; Cote, C.H.; Salgado, R.; Sanchez, V.; et al. Tumor-specific MHC-II expression drives a unique pattern of resistance to immunotherapy via LAG-3/FCRL6 engagement. JCI insight 2018, 3. [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Akbay, E.A.; Li, Y.Y.; Herter-Sprie, G.S.; Buczkowski, K.A.; Richards, W.G.; Gandhi, L.; Redig, A.J.; Rodig, S.J.; Asahina, H.; et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10501. [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.T.; Salmena, L. Recent advances in PTEN signalling axes in cancer. Faculty reviews 2020, 9, 31. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Richards, J.A.; Gupta, R.; Aung, P.P.; Emley, A.; Kluger, Y.; Dogra, S.K.; Mahalingam, M.; Wajapeyee, N. PTEN functions as a melanoma tumor suppressor by promoting host immune response. Oncogene 2014, 33, 4632-4642. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.; Palomo, I.; Fuentes, E. Role of adenosine A2b receptor overexpression in tumor progression. Life sciences 2016, 166, 92-99. [CrossRef]

- Crunkhorn, S. Reactivating PTEN promotes antitumour immunity. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2021, 20, 588. [CrossRef]

- Cucchiara, F.; Crucitta, S.; Petrini, I.; de Miguel Perez, D.; Ruglioni, M.; Pardini, E.; Rolfo, C.; Danesi, R.; Del Re, M. Gene-network analysis predicts clinical response to immunotherapy in patients affected by NSCLC. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2023, 183, 107308. [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, J.A.; Luke, J.J.; Zha, Y.; Segal, J.P.; Ritterhouse, L.L.; Spranger, S.; Matijevich, K.; Gajewski, T.F. Secondary resistance to immunotherapy associated with β-catenin pathway activation or PTEN loss in metastatic melanoma. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2019, 7, 295. [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer cell 2023, 41, 374-403. [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nature reviews. Immunology 2021, 21, 485-498. [CrossRef]

- Poggio, M.; Hu, T.; Pai, C.C.; Chu, B.; Belair, C.D.; Chang, A.; Montabana, E.; Lang, U.E.; Fu, Q.; Fong, L.; et al. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell 2019, 177, 414-427.e413. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.W.; Chan, L.C.; Wei, Y.; Hsu, J.M.; Xia, W.; Cha, J.H.; Hou, J.; Hsu, J.L.; Sun, L.; et al. Exosomal PD-L1 harbors active defense function to suppress T cell killing of breast cancer cells and promote tumor growth. Cell research 2018, 28, 862-864. [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.; Hou, K.; Huang, Q.; Lei, Y.; Chen, W. Targeting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell, a Promising Strategy to Overcome Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 783. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.M.; Zhao, Q.; Peng, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.P.; Wu, C.; Zheng, L. Activated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease progression through PD-L1. The Journal of experimental medicine 2009, 206, 1327-1337. [CrossRef]

- Sprinzl, M.F.; Galle, P.R. Immune control in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression: role of stromal cells. Seminars in liver disease 2014, 34, 376-388. [CrossRef]

- De Henau, O.; Rausch, M.; Winkler, D.; Campesato, L.F.; Liu, C.; Cymerman, D.H.; Budhu, S.; Ghosh, A.; Pink, M.; Tchaicha, J.; et al. Overcoming resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by targeting PI3Kγ in myeloid cells. Nature 2016, 539, 443-447. [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2012, 366, 2443-2454. [CrossRef]

- Song, T.L.; Nairismägi, M.L.; Laurensia, Y.; Lim, J.Q.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.M.; Pang, W.L.; Kizhakeyil, A.; Wijaya, G.C.; Huang, D.C.; et al. Oncogenic activation of the STAT3 pathway drives PD-L1 expression in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 1146-1158. [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Formisano, L.; Gonzalez-Ericsson, P.I.; Sanchez, V.; Dean, P.T.; Opalenik, S.R.; Sanders, M.E.; Cook, R.S.; Arteaga, C.L.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Melanoma response to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy requires JAK1 signaling, but not JAK2. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1438106. [CrossRef]

- Dillen, A.; Bui, I.; Jung, M.; Agioti, S.; Zaravinos, A.; Bonavida, B. Regulation of PD-L1 Expression by YY1 in Cancer: Therapeutic Efficacy of Targeting YY1. Cancers 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wei, J.; Xue, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Zheng, L.; Duan, Y.; Deng, H.; Xiong, W.; Tang, F.; et al. Dissecting the roles and clinical potential of YY1 in the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in oncology 2023, 13, 1122110. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; Garcia-Diaz, A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Kalbasi, A.; Grasso, C.S.; Hugo, W.; Sandoval, S.; Torrejon, D.Y.; et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer discovery 2017, 7, 188-201. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.A.; Kouzarides, T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 2012, 150, 12-27. [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; De Palma, R.; Altucci, L. HDAC inhibitors as epigenetic regulators for cancer immunotherapy. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2018, 98, 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Quiros, J.; Mahuron, K.; Pai, C.C.; Ranzani, V.; Young, A.; Silveria, S.; Harwin, T.; Abnousian, A.; Pagani, M.; et al. Targeting EZH2 Reprograms Intratumoral Regulatory T Cells to Enhance Cancer Immunity. Cell reports 2018, 23, 3262-3274. [CrossRef]

- Keir, M.E.; Butte, M.J.; Freeman, G.J.; Sharpe, A.H. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annual review of immunology 2008, 26, 677-704. [CrossRef]

- Perrier, A.; Didelot, A.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Blons, H.; Garinet, S. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Kobayashi, A.; Jiang, P.; Ferrari de Andrade, L.; Tay, R.E.; Luoma, A.M.; Tsoucas, D.; Qiu, X.; Lim, K.; Rao, P.; et al. A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2018, 359, 770-775. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Peng, Y.; Ge, Z.; Nagel, Z.D.; Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Kapoor, P.; et al. ARID1A deficiency promotes mutability and potentiates therapeutic antitumor immunity unleashed by immune checkpoint blockade. Nature medicine 2018, 24, 556-562. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Adam, A.; Zhao, C.; Chen, H. Recent Advancements in the Mechanisms Underlying Resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Emran, A.A.; Chatterjee, A.; Rodger, E.J.; Tiffen, J.C.; Gallagher, S.J.; Eccles, M.R.; Hersey, P. Targeting DNA Methylation and EZH2 Activity to Overcome Melanoma Resistance to Immunotherapy. Trends in immunology 2019, 40, 328-344. [CrossRef]

- Madore, J.; Strbenac, D.; Vilain, R.; Menzies, A.M.; Yang, J.Y.; Thompson, J.F.; Long, G.V.; Mann, G.J.; Scolyer, R.A.; Wilmott, J.S. PD-L1 Negative Status is Associated with Lower Mutation Burden, Differential Expression of Immune-Related Genes, and Worse Survival in Stage III Melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016, 22, 3915-3923. [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine 2015, 372, 2521-2532. [CrossRef]

- Perez, H.L.; Cardarelli, P.M.; Deshpande, S.; Gangwar, S.; Schroeder, G.M.; Vite, G.D.; Borzilleri, R.M. Antibody-drug conjugates: current status and future directions. Drug discovery today 2014, 19, 869-881. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, J.; Page, D.B.; Li, B.T.; Connell, L.C.; Schindler, K.; Lacouture, M.E.; Postow, M.A.; Wolchok, J.D. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2015, 26, 2375-2391. [CrossRef]

- Spain, L.; Diem, S.; Larkin, J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer treatment reviews 2016, 44, 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Havel, J.J.; Chowell, D.; Chan, T.A. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Cancer 2019, 19, 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; McLeod, H.L. Prospect for immune checkpoint blockade: dynamic and comprehensive monitorings pave the way. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 1299-1304. [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Jiao, D.; Xu, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Han, X.; Wu, K. Biomarkers for predicting efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Molecular cancer 2018, 17, 129. [CrossRef]

- Vilain, R.E.; Menzies, A.M.; Wilmott, J.S.; Kakavand, H.; Madore, J.; Guminski, A.; Liniker, E.; Kong, B.Y.; Cooper, A.J.; Howle, J.R.; et al. Dynamic Changes in PD-L1 Expression and Immune Infiltrates Early During Treatment Predict Response to PD-1 Blockade in Melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2017, 23, 5024-5033. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Fang, W.; Zhan, J.; Hong, S.; Tang, Y.; Kang, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Zhou, T.; Qin, T.; et al. Upregulation of PD-L1 by EGFR Activation Mediates the Immune Escape in EGFR-Driven NSCLC: Implication for Optional Immune Targeted Therapy for NSCLC Patients with EGFR Mutation. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 2015, 10, 910-923. [CrossRef]

- Gainor, J.F.; Shaw, A.T.; Sequist, L.V.; Fu, X.; Azzoli, C.G.; Piotrowska, Z.; Huynh, T.G.; Zhao, L.; Fulton, L.; Schultz, K.R.; et al. EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016, 22, 4585-4593. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.L. Precision immunology: the promise of immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33, 1315-1317. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; Kvistborg, P.; Makarov, V.; Havel, J.J.; Lee, W.; Yuan, J.; Wong, P.; Ho, T.S.; et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2015, 348, 124-128. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; Canal, F.; Scarpa, M.; Basato, S.; Erroi, F.; Fiorot, A.; Dall'Agnese, L.; Pozza, A.; Porzionato, A.; et al. Mismatch repair gene defects in sporadic colorectal cancer enhance immune surveillance. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43472-43482. [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. The New England journal of medicine 2015, 372, 2509-2520. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, H.; Zaanan, A.; Sinicrope, F.A. Microsatellite instability testing and its role in the management of colorectal cancer. Current treatment options in oncology 2015, 16, 30. [CrossRef]

- Delyon, J.; Mateus, C.; Lefeuvre, D.; Lanoy, E.; Zitvogel, L.; Chaput, N.; Roy, S.; Eggermont, A.M.; Routier, E.; Robert, C. Experience in daily practice with ipilimumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: an early increase in lymphocyte and eosinophil counts is associated with improved survival. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2013, 24, 1697-1703. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, S.; Koyama, S.; Itahashi, K.; Tanegashima, T.; Lin, Y.T.; Togashi, Y.; Kamada, T.; Irie, T.; Okumura, G.; Kono, H.; et al. Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer cell 2022, 40, 201-218.e209. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.A.; Amir, E. HYPE or HOPE: the prognostic value of infiltrating immune cells in cancer. British journal of cancer 2018, 118, e5. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.; Stromhaug, K.; Klaeger, S.; Kula, T.; Frederick, D.T.; Le, P.M.; Forman, J.; Huang, T.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; et al. Phenotype, specificity and avidity of antitumour CD8(+) T cells in melanoma. Nature 2021, 596, 119-125. [CrossRef]

- Luoma, A.M.; Suo, S.; Wang, Y.; Gunasti, L.; Porter, C.B.M.; Nabilsi, N.; Tadros, J.; Ferretti, A.P.; Liao, S.; Gurer, C.; et al. Tissue-resident memory and circulating T cells are early responders to pre-surgical cancer immunotherapy. Cell 2022, 185, 2918-2935.e2929. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Fearon, D.T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2015, 348, 74-80. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Puri, S.; Moudgil, T.; Wood, W.; Hoyt, C.C.; Wang, C.; Urba, W.J.; Curti, B.D.; Bifulco, C.B.; Fox, B.A. Multispectral imaging of formalin-fixed tissue predicts ability to generate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from melanoma. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2015, 3, 47. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, X.; Feng, K.; Gao, R.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Corse, E.; Hu, Y.; Han, W.; et al. Temporal single-cell tracing reveals clonal revival and expansion of precursor exhausted T cells during anti-PD-1 therapy in lung cancer. Nature cancer 2022, 3, 108-121. [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.C.; Sen, D.R.; Al Abosy, R.; Bi, K.; Virkud, Y.V.; LaFleur, M.W.; Yates, K.B.; Lako, A.; Felt, K.; Naik, G.S.; et al. Subsets of exhausted CD8(+) T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nature immunology 2019, 20, 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Tsui, C.; Kretschmer, L.; Rapelius, S.; Gabriel, S.S.; Chisanga, D.; Knöpper, K.; Utzschneider, D.T.; Nüssing, S.; Liao, Y.; Mason, T.; et al. MYB orchestrates T cell exhaustion and response to checkpoint inhibition. Nature 2022, 609, 354-360. [CrossRef]

- Galletti, G.; De Simone, G.; Mazza, E.M.C.; Puccio, S.; Mezzanotte, C.; Bi, T.M.; Davydov, A.N.; Metsger, M.; Scamardella, E.; Alvisi, G.; et al. Two subsets of stem-like CD8(+) memory T cell progenitors with distinct fate commitments in humans. Nature immunology 2020, 21, 1552-1562. [CrossRef]

- Beltra, J.C.; Manne, S.; Abdel-Hakeem, M.S.; Kurachi, M.; Giles, J.R.; Chen, Z.; Casella, V.; Ngiow, S.F.; Khan, O.; Huang, Y.J.; et al. Developmental Relationships of Four Exhausted CD8(+) T Cell Subsets Reveals Underlying Transcriptional and Epigenetic Landscape Control Mechanisms. Immunity 2020, 52, 825-841.e828. [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Skaarup Larsen, M.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561-565. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.D.; Madireddi, S.; de Almeida, P.E.; Banchereau, R.; Chen, Y.J.; Chitre, A.S.; Chiang, E.Y.; Iftikhar, H.; O'Gorman, W.E.; Au-Yeung, A.; et al. Peripheral T cell expansion predicts tumour infiltration and clinical response. Nature 2020, 579, 274-278. [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Chaft, J.E.; Smith, K.N.; Anagnostou, V.; Cottrell, T.R.; Hellmann, M.D.; Zahurak, M.; Yang, S.C.; Jones, D.R.; Broderick, S.; et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, 1976-1986. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Quinn, R.A.; Debelius, J.; Xu, Z.Z.; Morton, J.; Garg, N.; Jansson, J.K.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Knight, R. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature 2016, 535, 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Zitvogel, L.; Straussman, R.; Hasty, J.; Wargo, J.A.; Knight, R. The microbiome and human cancer. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2021, 371. [CrossRef]

- Kraehenbuehl, L.; Weng, C.H.; Eghbali, S.; Wolchok, J.D.; Merghoub, T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 2022, 19, 37-50. [CrossRef]

- Tawbi, H.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Castillo Gutiérrez, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; De Menezes, J.J.; et al. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine 2022, 386, 24-34. [CrossRef]

- Ezdoglian, A.; Tsang, A.S.M.; Khodadust, F.; Burchell, G.; Jansen, G.; de Gruijl, T.; Labots, M.; van der Laken, C.J. Monocyte-related markers as predictors of immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy and immune-related adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer metastasis reviews 2025, 44, 35. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Koh, J.; Kim, S.; Yim, J.; Song, S.G.; Kim, H.; Li, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Chung, Y.K.; Kim, H.; et al. Cell-intrinsic PD-L1 signaling drives immunosuppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells through IL-6/Jak/Stat3 in PD-L1-high lung cancer. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Strati, A.; Adamopoulos, C.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A.; Lianidou, E.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Signaling Pathway for Cancer Therapy: Focus on Biomarkers. International journal of molecular sciences 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Su, J. Predictive Value of the Lung Immune Prognostic Index for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iranian journal of allergy, asthma, and immunology 2025, 24, 132-142. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Buzdin, A.; Mu, X.; Yan, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chang, H.H.; Duhon, M.; et al. FDA-Approved and Emerging Next Generation Predictive Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Patients. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11, 683419. [CrossRef]

- Man, J.; Millican, J.; Mulvey, A.; Gebski, V.; Hui, R. Response Rate and Survival at Key Timepoints With PD-1 Blockade vs Chemotherapy in PD-L1 Subgroups: Meta-Analysis of Metastatic NSCLC Trials. JNCI cancer spectrum 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.; Singh, H.; Larkins, E.; Drezner, N.; Ricciuti, B.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.; Tang, S.; Beaver, J.A.; Awad, M.M. Impact of Increasing PD-L1 Levels on Outcomes to PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibition in Patients With NSCLC: A Pooled Analysis of 11 Prospective Clinical Trials. The oncologist 2024, 29, 422-430. [CrossRef]

- Taube, J.M.; Klein, A.; Brahmer, J.R.; Xu, H.; Pan, X.; Kim, J.H.; Chen, L.; Pardoll, D.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Anders, R.A. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2014, 20, 5064-5074. [CrossRef]

- Zdrenka, M.; Kowalewski, A.; Ahmadi, N.; Sadiqi, R.U.; Chmura, Ł.; Borowczak, J.; Maniewski, M.; Szylberg, Ł. Refining PD-1/PD-L1 assessment for biomarker-guided immunotherapy: A review. Biomolecules & biomedicine 2024, 24, 14-29. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, 2078-2092. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Xia, W.; Chen, C.H.; Rau, K.M.; Ye, L.; Wei, Y.; Chou, C.K.; Wang, S.C.; Yan, M.; et al. Removal of N-Linked Glycosylation Enhances PD-L1 Detection and Predicts Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Therapeutic Efficacy. Cancer cell 2019, 36, 168-178.e164. [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Gu, D.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. A comparability study of natural and deglycosylated PD-L1 levels in lung cancer: evidence from immunohistochemical analysis. Molecular cancer 2021, 20, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Song, Y.; Deng, W.; Blake, N.; Luo, X.; Meng, J. Potential predictive biomarkers in antitumor immunotherapy: navigating the future of antitumor treatment and immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy. Frontiers in oncology 2024, 14, 1483454. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, B.; Van Campenhout, C.; Rorive, S.; Remmelink, M.; Salmon, I.; D'Haene, N. Methods of measurement for tumor mutational burden in tumor tissue. Translational lung cancer research 2018, 7, 661-667. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, L.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.A.; Donoghue, M.; Yuan, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Gallagher, P.S.; Philip, R.; Ghosh, S.; Theoret, M.R.; Beaver, J.A.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden-High Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2021, 27, 4685-4689. [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti, B.; Wang, X.; Alessi, J.V.; Rizvi, H.; Mahadevan, N.R.; Li, Y.Y.; Polio, A.; Lindsay, J.; Umeton, R.; Sinha, R.; et al. Association of High Tumor Mutation Burden in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers With Increased Immune Infiltration and Improved Clinical Outcomes of PD-L1 Blockade Across PD-L1 Expression Levels. JAMA oncology 2022, 8, 1160-1168. [CrossRef]

- Florou, V.; Floudas, C.S.; Maoz, A.; Naqash, A.R.; Norton, C.; Tan, A.C.; Sokol, E.S.; Frampton, G.; Soares, H.P.; Puri, S.; et al. Real-world pan-cancer landscape of frameshift mutations and their role in predicting responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancers with low tumor mutational burden. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Georgoulias, G.; Zaravinos, A. Genomic landscape of the immunogenicity regulation in skin melanomas with diverse tumor mutation burden. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 1006665. [CrossRef]

- Bonneville, R.; Krook, M.A.; Kautto, E.A.; Miya, J.; Wing, M.R.; Chen, H.Z.; Reeser, J.W.; Yu, L.; Roychowdhury, S. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO precision oncology 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Marabelle, A.; O'Malley, D.M.; Hendifar, A.E.; Ascierto, P.A.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Penel, N.; Cassier, P.A.; Bariani, G.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Doi, T.; et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability-high and mismatch-repair-deficient advanced solid tumors: updated results of the KEYNOTE-158 trial. Nature cancer 2025, 6, 253-258. [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Nie, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Y. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: current achievements and future perspective. International journal of biological sciences 2021, 17, 3837-3849. [CrossRef]

- McGrail, D.J.; Pilié, P.G.; Rashid, N.U.; Voorwerk, L.; Slagter, M.; Kok, M.; Jonasch, E.; Khasraw, M.; Heimberger, A.B.; Ueno, N.T.; et al. Validation of cancer-type-dependent benefit from immune checkpoint blockade in TMB-H tumors identified by the FoundationOne CDx assay. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2022, 33, 1204-1206. [CrossRef]

- Mucherino, S.; Lorenzoni, V.; Triulzi, I.; Del Re, M.; Orlando, V.; Capuano, A.; Danesi, R.; Turchetti, G.; Menditto, E. Cost-Effectiveness of Treatment Optimisation with Biomarkers for Immunotherapy in Solid Tumours: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor resistance in cancer treatment: Current progress and future directions. Cancer letters 2023, 562, 216182. [CrossRef]

- Bell, H.N.; Zou, W. Beyond the Barrier: Unraveling the Mechanisms of Immunotherapy Resistance. Annual review of immunology 2024, 42, 521-550. [CrossRef]

- Heinhuis, K.M.; Ros, W.; Kok, M.; Steeghs, N.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. Enhancing antitumor response by combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in solid tumors. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2019, 30, 219-235. [CrossRef]

- Moya-Horno, I.; Viteri, S.; Karachaliou, N.; Rosell, R. Combination of immunotherapy with targeted therapies in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Therapeutic advances in medical oncology 2018, 10, 1758834017745012. [CrossRef]

- Starzer, A.M.; Wolff, L.; Popov, P.; Kiesewetter, B.; Preusser, M.; Berghoff, A.S. The more the merrier? Evidence and efficacy of immune checkpoint- and tyrosine kinase inhibitor combinations in advanced solid cancers. Cancer treatment reviews 2024, 125, 102718. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Li, S.C.; He, Q.J.; Yang, B.; Cao, J. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Uzar, W.; Kaminska, B.; Rybka, H.; Skalniak, L.; Magiera-Mularz, K.; Kitel, R. An updated patent review on PD-1/PD-L1 antagonists (2022-present). Expert opinion on therapeutic patents 2024, 34, 627-650. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Wei, M.; Zuo, Z.; Su, Q. Small-Molecule Drugs in Immunotherapy. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry 2023, 23, 1341-1359. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, J.; Ding, C.; Jin, Y.; Cui, X.; Pu, K.; Zhu, Y. Peptide Blocking of PD-1/PD-L1 Interaction for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer immunology research 2018, 6, 178-188. [CrossRef]

- Kamijo, H.; Sugaya, M.; Takahashi, N.; Oka, T.; Miyagaki, T.; Asano, Y.; Sato, S. BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 decreases CD30 and CCR4 expression and proliferation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell lines. Archives of dermatological research 2017, 309, 491-497. [CrossRef]