1. Introduction

Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) is the mainstay of prostate cancer treatment, especially in the metastatic disease. The rationale is reducing the serum testosterone levels below the castration threshold and so reducing the activation of AR and the prostate cancer cell growth [

1]. The Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonists bind GnRH receptor in the pituitary gland determining reduced production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and, therefore, testosterone. Notably, the non-pulsatile stimulation of GnRH receptors by agonists initially causes a surge in LH and testosterone, defined “testosterone surge” or “flare-up phenomenon”; however, sustained continuous stimulation results in receptor downregulation over a few weeks. [

1] With this rationale a short course of bicalutamide (3-4 weeks) is generally required at the beginning of a GnRH agonist treatment in order to control the possible initial increase of testosterone eventually impacting disease progression.

The flare-up phenomenon occurs in about 10% of patients treated with GnRH agonist [

2]. Testosterone levels increase by a maximum of 2-fold starting on day 2-4 and decrease to baseline values in about 1 week [

3]. The correlation between testosterone flare and progression of prostate cancer has not been proved, but this phenomenon could in theory increase bone pain, spinal cord compression, bladder outlet obstruction and cardiovascular problems [

4]. However, while GnRH agonist monotherapy seems to be safe in patients with low stage disease and low bone involvement, the testosterone surge could exacerbate complications in patients with advanced disease, i.e., high volume bony disease [

4,

5]. For those patients, the European Association of Urology (EAU) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend the association of a first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) with GnRH agonists. The recommendation suggests administering the anti-androgen for at least 7 days before starting GnRH in order to manage potential increases in testosterone levels and mitigate risks of adverse events (weak recommendation) [

2,

4,

6].

Second generation Androgen Receptor Targeted Agents (ARTA) (apalutamide, enzalutamide, darolutamide) exhibit a more efficient inhibition of the AR pathway compared to first-generation agents. Not only they bind to the Ligand Binding Domain, but also prevent AR translocation into the nucleus and the recruitment of co-activators [

7].

In particular, apalutamide is a selective AR inhibitor that binds AR with 7- to 10-fold greater affinity than bicalutamide. The antitumor activity of bicalutamide was largely restricted to growth inhibition rather than tumor shrinkage, while apalutamide induced significant tumor regression. Unlike first-generation anti-androgens (eg, bicalutamide), apalutamide selectively and irreversibly binds to the AR with high affinity and exhibits minimal binding to other hormonal and neurotransmitter receptors [

8].

ARTA demonstrated a significant improvement in oncological outcomes both in castration resistant (CRPC) and metastatic hormone-sensitive (mHSPC) prostate cancer. In patients with mHSPC, apalutamide demonstrated a reduction of 52% for the risk of radiological progression and 48% for the risk of death after adjusting for crossover [

9]. Recently, Chowdhury et al. showed a reduction of up to 90% in Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) levels in patients enrolled in TITAN trial treated with apalutamide, versus a reduction of up to 55% in the placebo arm. Furthermore, the achievement of 90% PSA reduction or ≤0.2 ng/ml in PSA levels at 3 months was associated with improvement in overall survival, radiological progression-free survival, time to PSA progression and time to CRPC [

10].

In these studies, apalutamide 240mg plus GnRH agonist was administered after an induction period of 14 days with a first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide). This approach accounts for the double-blind design of the trials and addresses the flare phenomenon in the placebo arm [

9,

10]

Considering the more efficient block of AR by ARTA, the use of these drugs following a first-generation agent determine only a redundancy in pharmacological action without a proven benefit. Furthermore, given the prognostic role of a rapid and deep PSA decline in patients treated with apalutamide on oncological outcome, it is of paramount importance to start the treatment with the most effective drug to accelerate the PSA response.

In the present report, we question the real utility of the association of first-generation antiandrogen to GnRH agonists at the beginning of an ARTA treatment. In fact, we describe our clinical experience with 14 days of apalutamide monotherapy followed by apalutamide plus GnRH agonist administration for the treatment of mHSPC.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive retrospective study of patients with mHSPC who were treated in first-line with apalutamide monotherapy for 14 days (to prevent flare up phenomenon) followed by continuous combination with GnRH agonist plus apalutamide at the Oncology Complex Unit of the “S. Maria delle Grazie” Hospital, Pozzuoli, Italy, between June 2022 and April 2024. Inclusion criteria were a confirmed diagnosis of mHSPC, absence of previous hormonal treatments for metastatic disease, and provided informed consent to participate. Patients included in other clinical trials were excluded. The protocol was approved by Campania 1 Ethical Committee.

Treatment consisted of apalutamide monotherapy at the dose of 240 mg orally once per day from day 1 to day 13, subsequently associated with a GnRH agonist from day 14. Treatment combination was continued until progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred, according to clinical practice. Serum PSA and testosterone levels were measured at baseline (at starting frontline treatment with apalutamide alone), at day 14 (after 13 days of apalutamide monotherapy), at day 28 (after additional 15 days of apalutamide plus a GnRH agonist), and at day 60. Undetectable PSA was defined as a value ≤0.2 ng/ml.

Selected patients and disease characteristics were recorded at diagnosis and/or at starting frontline apalutamide treatment, including age, Gleason score, tumour stage, presence of comorbidities, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) and disease volume, classified according to the definition given in the CHAARTED trial [

11].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize PSA and testosterone changes over time and the toxicity profile. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean values ± standard deviations, and categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups (i.e., low vs high volume disease) were performed using the contingency table analysis with the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate (for categorical data), and through a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for continuous data). Toxicities were tabulated, both overall and according to their grade. Analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Patients’ Characteristics

A total of 27 mHSPC patients treated with apalutamide monotherapy followed, after 14 days, by the addition of a GnRH agonist were considered in the present analysis. At prostate cancer diagnosis the mean patient age was 68.2 (±6.9) years, with 15 patients (44.4%) presenting de novo metastases. At the start of frontline apalutamide treatment, the mean age was 71.1 (±7.4) years. The large majority of patients (85.2%) had ECOG PS of 0, and 17 (63.0%) and 10 (37.0%) patients had, respectively, low- and high-volume disease. The Gleason score was equal to 7 in 8 patients (30.8%), 8 in 12 patients (46.1%) and ≥9 in 6 patients (23.1%) (the sum does not add up to the total because of 1 missing information -

Table 1).

3.2. Decrease in PSA Levels

PSA levels decreased from a mean of 45.2 (±63.1) ng/ml at baseline to a mean of 12.6 (±23.4) ng/ml at day 14 and to 3.3 ng/ml (±6.0) at day 28 (

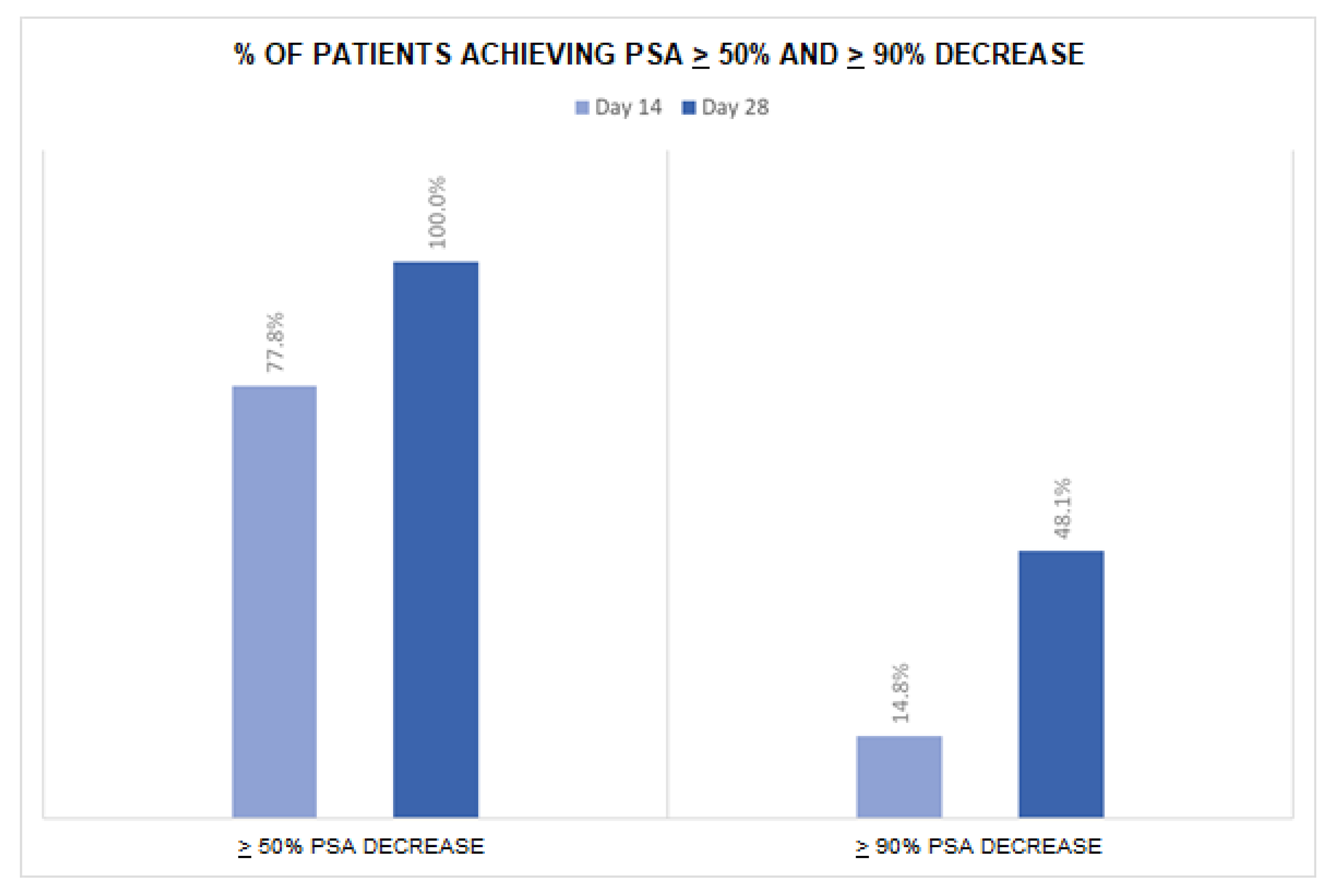

Table 2). After 14 days of apalutamide monotherapy, 21 patients (77.8%) achieved a ≥50% PSA reduction and 4 (14.8%) a ≥90% PSA reduction (

Figure 1). At day 28 (after additional 14 days of apalutamide monotherapy and 14 days of apalutamide plus GnRH agonist), 27 patients (100%) achieved a ≥50% PSA reduction and 13 (48.1%) a ≥90% PSA reduction. The number of patients with undetectable PSA was 1 (3.7%) at day 14, 2 (7.4%) at day 28 and 9 (33.3%) at day 60. Overall, 20 patients (74.1%) achieved undetectable PSA at any time in the first 28 days of treatment. No significant difference in PSA levels or PSA reduction emerged between subgroups of patients with low vs. high volume disease (all p-values were >0.05).

3.3. Decrease in Testosterone Levels

The mean serum testosterone levels were 6.56 (± 4.46) ng/ml at baseline, 6.58 (± 4.42) ng/ml at day 14, and 2.40 (± 3.38) ng/ml at day 28 (

Table S1). A total of 6 patients (22.2%) had a reduction in testosterone levels at day 14, with 1 patient experiencing a ≥90% reduction from the baseline value. At day 28, 24 patients (88.9%) showed a testosterone decrease, with 20 patients (74.1%) achieving a ≥50% and 8 (29.6%) a ≥90% reduction. No significant difference in testosterone levels or testosterone decrease was reported across subgroups of disease volume (all p-values were >0.05).

3.4. Toxicities

During treatment, 16 patients (59.3%) reported toxicities, the most common one being those of the skin (n=11, 40.7%, [G1-2: n=6, G3: n=5]). Three patients (11.1%) had hypertension, 1 (3.7%) reported cardiopathy and 1 (3.7%) hypothyroidism. No patient reported signs or symptoms caused by flare-up during the observation period (see

Table S2).

4. Discussion

This is one of the first studies describing, as a single centre experience, the biochemical response and toxicity of frontline apalutamide monotherapy followed by the addition of GnRH agonist administration in a series of mHSPC patients without the need of first generation anti-androgen to avoid the flare up phenomenon. We observed a rapid lowering in PSA levels after two weeks of apalutamide monotherapy treatment, which further declined after additional two weeks of the combination apalutamide + GnRH agonist. Furthermore, all patients reached optimal castration level in the first month of treatment. No new adverse events were reported, and the toxicity profile was consistent with previous studies.

The efficacy of apalutamide plus GnRH agonist therapy on PSA levels, and the association between a deep and rapid PSA control with clinical outcomes was demonstrated for patients with mHSPC in the TITAN phase III trial [

10]. In our cohort, over two-thirds of patients had >50% PSA level reduction (77.8%), with 15% achieving a ≥90% decline, as soon as only 14 days of treatment with apalutamide monotherapy, thus demonstrating the high AR-binding affinity and efficacy of the drug, even in the normal testosterone level phase in the absence of combined GnRH agonist therapy. Importantly, the effect of apalutamide on the decrease of PSA values was rapid, with noticeable results apparent after just 14 days of treatment. Literature data on this topic from Real-World studies are particularly scanty. Our findings thus provide useful new insights of potential relevance for the management of mHSPC in everyday clinical practice.

Various international guidelines recommend short-term use of anti-androgenic treatment in newly diagnosed HSPC cases before starting GnRH agonists in order to mitigate the flare consequences, although the strength of the evidence is weak [

6,

12]. Our results support the use of apalutamide alone to protect against testosterone surge, and allows a PSA control, avoiding first generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide). Mean testosterone level, in fact, remained materially unchanged after 2 weeks of apalutamide alone in the majority of patients, while it decreased strongly (by almost two-thirds) after 2 subsequent weeks of apalutamide + GnRH agonist therapy. Previous information is limited, particularly from the clinical practice setting. In a case-report from China, one patient with newly diagnosed mHSPC underwent the same treatment schedule, reporting an upward trend in testosterone levels during the first two weeks, followed by a rapid decline during the period of combined therapy with apalutamide and GnRH agonists [

13]. Similar results emerged in a phase II open-label trial including a study arm of 42 patients with advanced HSPC treated with apalutamide alone [

14].

Major limitations of this study are its observational design and mainly descriptive aims. No comparison groups were available and the size of the mHSPC population was limited. Still, this exploratory analysis from a real-life setting may provide relevant clinical indications and promote new studies on the topic.

5. Conclusions

According to our findings, apalutamide alone is a viable option for mitigating the flare up phenomenon avoiding first generation anti-androgen therapy (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide); it is able to achieve a rapid and deep biochemical control and allows to start the most effective therapy earlier. In conclusion, our findings support a significant change in clinical practice for first-line patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) who can benefit immediately from a new androgen receptor targeting agent (ARTA) such as apalutamide to mitigate the flare up phenomenon and to achieve a rapid and deep biochemical control. Further studies are needed to confirm this results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Testosterone levels and proportion of patients achieving testosterone reduction at 14 and 28 days, overall and according to disease volume; Table S2: Toxicities reported during treatment in 27 patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F. Validation, G.F., L.F., E.M., M.B., S.P. Supervision, G. F. Writing – Original Draft Preparation, C.B., A.D., A.N. Writing – Review & Editing, F.F., M.I., L.M., G.C. Data Curation, C.L., R.A.C., P.C., A.M., M.T.D.N. Investigation, F.R., G.M.F., F.T., G.D.L., G.D.C., A. T., F.I., L.D.L., S.M. Funding Acquisition, G.F. Formal Analysis, G.F., M.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Campania I (protocol code 5/25 OSS ASL NA 2 Nord approved on 29-Apr-2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

No technical support was received for statistical analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADT |

Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| GnRH |

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| mHSPC |

metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer |

| PSA |

Prostate Specific Antigen |

| LH |

luteinizing hormone |

| FSH |

follicle-stimulating hormone |

| EAU |

European Association of Urology |

| ARTA |

Androgen Receptor Targeted Agents |

| AR |

Androgen Receptor |

| CRPC |

Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| ECOG PS |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status |

References

- Crawford, E.D.; Heidenreich, A.; Androgen-targeted therapy in men with prostate cancer: evolving practice and future considerations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2019, [22] (p. 24-38). [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.K.; Landrum, M.B.; Does oral antiandrogen use before leuteinizing hormone-releasing hormone therapy in patients with metastatic prostate cancer prevent clinical consequences of a testosterone flare? Urology, 2010, [75] (p. 642-647). [CrossRef]

- Krakowsky, Y.; Morgentaler, A.; Risk of Testosterone Flare in the Era of the Saturation Model: One More Historical Myth. Eur Urol Focus, 2019, [5] (p. 81-89). [CrossRef]

- Bubley, G.J.; Is the flare phenomenon clinically significant? Urology, 2001, [58] (p. 5-9). [CrossRef]

- Cornford P., Tilki D.; EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. 2025.

- Spratt, D.E.; Srinivas, S.; Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2025.

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Second generation androgen receptor antagonists and challenges in prostate cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis, 2022, [13] (p. 632). [CrossRef]

- Clegg, N.J.; Wongvipat, J.; ARN-509: a novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Res, 2012, [72] (p. 1494-1503). [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Agarwal, N.; Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2019, [381] (p. 13-24). [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Bjartell, A.; Deep, rapid, and durable prostate-specific antigen decline with apalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy is associated with longer survival and improved clinical outcomes in TITAN patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Ann Oncol, 2023, [34] (p. 477-485). [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, C.E.; Chen, Y.H.; Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Survival Analysis of the Randomized Phase III E3805 CHAARTED Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2018, [36] (p. 1080-1087). [CrossRef]

- Tilki, D.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II-2024 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2024, [86] (p. 164-182). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Absence of PSA Flare With Apalutamide Administered 1 Hour in Advance With GnRH Agonists: Case Report. Front Oncol, 2022, [12] (p. 878264). [CrossRef]

- Maluf, F.C.; Schutz, F.A.; A phase 2 randomized clinical trial of abiraterone plus ADT, apalutamide, or abiraterone and apalutamide in patients with advanced prostate cancer with non-castrate testosterone levels (LACOG 0415). Eur J Cancer, 2021, [158] (p. 63-71). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).