Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The introduction of the ⵟ-product, a novel, physics-grounded neural operator that unifies directional sensitivity with an inverse-square proximity measure, designed for geometrically faithful similarity assessment.

- The proposal of Neural-Matter Networks (NMNs), a new class of neural architectures based on the ⵟ-product, which inherently incorporate non-linearity and are designed to preserve input topology.

- The development and pretraining of AetherGPT, a transformer model based on GPT-2 architectural principles incorporating the ⵟ-product, pretrained on the FineWeb 10B dataset, serving as an initial large-scale validation of the proposed concepts.

- A commitment to open science through the release of all associated code and models under the Affero GNU General Public License.

2. Related Work

2.1. Inverse-Square Laws

2.2. Learning with Kernels

2.3. Deep Learning

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Revisiting Core Computational Primitives and Similarity Measures

3.1.1. The Dot Product: A Measure of Alignment

3.1.2. The Convolution Operator: Localized Feature Mapping

- Feature Detection: Kernels learn to identify localized patterns (edges, textures, motifs) at various abstraction levels.

- Spatial Hierarchy: Stacking layers allows the model to build complex feature representations from simpler ones.

- Parameter Sharing: Applying the same kernel across spatial locations enhances efficiency and translation equivariance.

3.1.3. Cosine Similarity: Normalizing for Directional Agreement

3.1.4. Euclidean Distance: Quantifying Spatial Proximity

3.2. The Role and Geometric Cost of Non-Linear Activation

3.2.1. Linear Separability and the Limitations of the Inner Product

3.2.2. Non-Linear Feature Space Transformation via Hidden Layers and Its Geometric Cost

3.2.3. Topological Distortions and Information Loss via Activation Functions

-

Non-Injectivity and Collapsing Regions: Many common activation functions render the overall mapping T non-injective.

- ReLU (): Perhaps the most prominent example. For each hidden neuron i, the entire half-space defined by is mapped to . Distinct points within this region, potentially far apart, become indistinguishable along the i-th dimension of the hidden space. This constitutes a significant loss of information about the relative arrangement of data points within these collapsed regions. The mapping is fundamentally many-to-one. For instance, consider two input vectors that are anti-aligned with a neuronś weight vector to different degrees—one strongly and one weakly. A ReLU activation function would map both resulting negative dot products to zero, rendering their distinct geometric opposition indistinguishable to subsequent layers. This information is irretrievably discarded.

- Sigmoid/Tanh: While smooth, these functions saturate. Inputs and that are far apart but both fall into the saturation regime (e.g., large positive or large negative values) will map to . This ’squashing’ effect can merge distinct clusters from the input space if they map to saturated regions in the hidden space, again losing discriminative information and distorting the metric structure.

- Distortion of Neighborhoods: The relative distances between points can be severely distorted. Points close in the input space might be mapped far apart in , or vice-versa (especially due to saturation or the zero-region of ReLU). This means the local neighborhood structure is not faithfully preserved. Formally, the mapping T is generally not a homeomorphism onto its image, nor is it typically bi-Lipschitz (which would provide control over distance distortions).

4. Methodology: A Framework for Geometry-Aware Computation

4.1. The ⵟ-Product: A Unified Operator for Alignment and Proximity

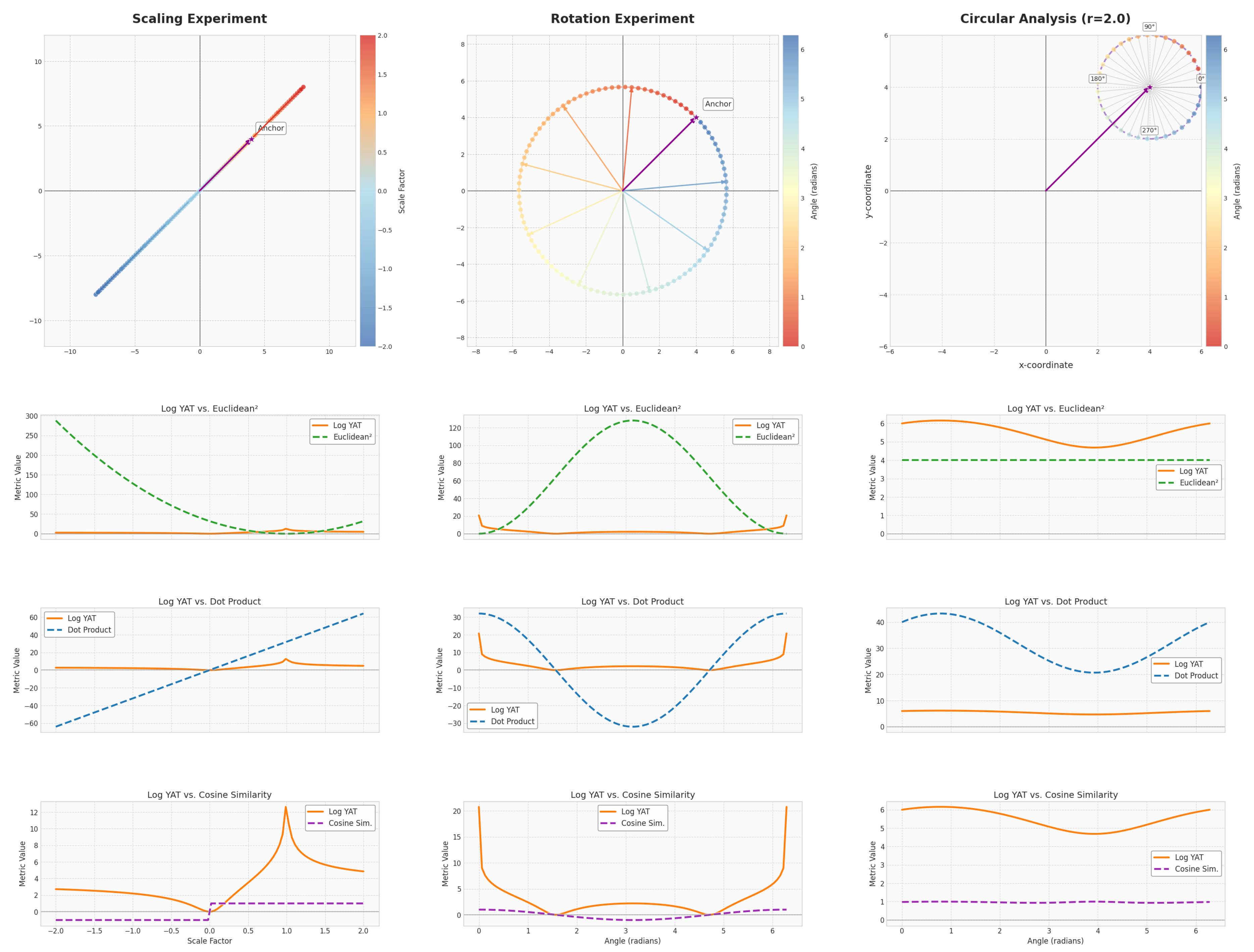

- Dot Product (): The dot product measures the projection of one vector onto another, thus capturing both alignment and magnitude. A larger magnitude in either vector, even with constant alignment, leads to a larger dot product. While useful, its direct sensitivity to magnitude can sometimes overshadow the pure geometric alignment.

- Cosine Similarity (): Cosine similarity normalizes the dot product by the magnitudes of the vectors, yielding the cosine of the angle between them. This makes it purely a measure of alignment, insensitive to vector magnitudes. However, as pointed out, this means it loses information about true distance or scale; two vectors can have perfect cosine similarity (e.g., value of 1) even if one is very distant from the other, as long as they point in the same direction.

- Euclidean Distance (): This metric computes the straight-line distance between the endpoints of two vectors. It is a direct measure of proximity. However, it does not inherently capture alignment. For instance, if is a reference vector, all vectors lying on the surface of a hypersphere centered at will have the same Euclidean distance to , regardless of their orientation relative to .

- ⵟ-Product (): The ⵟ-product uniquely combines aspects of both alignment and proximity in a non-linear fashion. The numerator, , emphasizes strong alignment (being maximal when vectors are collinear and zero when orthogonal) and is sensitive to magnitude. The denominator, , heavily penalizes large distances between and . This synergy allows the ⵟ-product to be highly selective. It seeks points that are not only well-aligned with the weight vector but also close to it. Unlike cosine similarity, it distinguishes between aligned vectors at different distances. Unlike Euclidean distance alone, it differentiates based on orientation. This combined sensitivity allows the ⵟ-product to identify matches with a high degree of specificity, akin to locating a point with "atomic level" precision, as it requires both conditions (alignment and proximity) to be met strongly for a high output.

4.2. Design Philosophy: Intrinsic Non-Linearity and Self-Regulation

4.3. Core Building Blocks

4.3.1. The Neural Matter Network (NMN) Layer

- is the weight vector of the i-th NMN unit.

- is the bias term for the i-th NMN unit.

- represents the ⵟ-product between the weight vector and the input .

- n is the number of NMN units in the layer.

- s is a scaling factor.

- a positive integer n (number of units),

- weight vectors for ,

- scalar bias terms for ,

- vector coefficients for ,

4.3.2. Convolutional Neural-Matter Networks (CNMNs) and the ⵟ-Convolution Layer

4.3.3. The ⵟ-Attention Mechanism

4.4. Architectural Implementations

- Fundamental Operator Replacement: The standard dot product is replaced by the ⵟ-product. This is manifested as ⵟ-Convolution (Equation ??) in convolutional networks and ⵟ-Attention (Equation 4.3.3) in transformer-based models.

- Feed-Forward Networks (FFNs): The FFNs within are constructed using NMN layers (Section 4.3.1) without explicit non-linear activation functions.

- Omission of Standard Layers: Consistent with this design philosophy, explicit activation functions and standard normalization layers are intentionally omitted.

4.4.1. Convolutional NMNs:

4.4.2. YatFormer: AetherGPT

4.5. Output Processing for Non-Negative Scores

- Standard Sigmoid Function (): When applied to non-negative inputs (), the standard sigmoid function produces outputs in the range . The minimum value of for renders it unsuitable for scenarios where small non-negative scores should map to values close to 0.

- Standard Softmax Function (): The use of the exponential function in softmax can lead to hard distributions, where one input value significantly dominates the output, pushing other probabilities very close to zero. While this is often desired for classification, it can be too aggressive if a softer assignment of probabilities or attention is preferred.

-

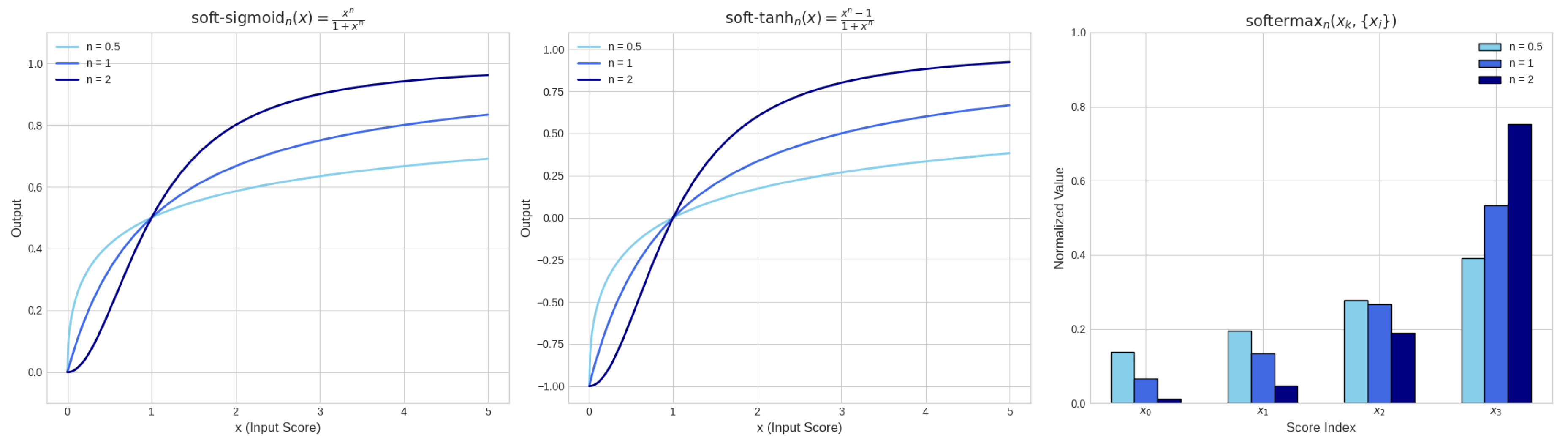

softermax: This function normalizes a score (optionally raised to a power ) relative to the sum of a set of non-negative scores (each raised to n), with a small constant for numerical stability. It is defined as:The power n controls the sharpness of the distribution: recovers the original Softermax, while makes the distribution harder (more peaked), and makes it softer.

-

soft-sigmoid: This function squashes a single non-negative score (optionally raised to a power ) into the range . It is defined as:The power n modulates the softness: higher n makes the function approach zero faster for large x, while makes the decay slower.

-

soft-tanh: This function maps a non-negative score (optionally raised to a power ) to the range by linearly transforming the output of soft-sigmoid. It is defined as:The power n again controls the transition sharpness: higher n makes the function approach more quickly for large x.Figure 6. Visualization of the softermax, soft-sigmoid, and soft-tanh functions. These functions are designed to handle non-negative inputs from the ⵟ-product and its derivatives, providing appropriate squashing mechanisms that maintain sensitivity across the range of non-negative inputs.Figure 6. Visualization of the softermax, soft-sigmoid, and soft-tanh functions. These functions are designed to handle non-negative inputs from the ⵟ-product and its derivatives, providing appropriate squashing mechanisms that maintain sensitivity across the range of non-negative inputs.

5. Results and Discussion

6. Explainability

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer

License

References

- Aki, Keiiti and Paul G. Richards. 2002. Quantitative Seismology (2 ed.). Sausalito, CA: University Science Books.

- Anderson, James E. 2011. The gravity model. Annual Review of Economics 3(1), 133–160. [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, G. K. 2000. An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Boser, Bernhard E., Isabelle M. Guyon, and Vladimir N. Vapnik. 1992. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Workshop on Computational Learning Theory, COLT ’92, New York, NY, USA, pp. 144–152. Association for Computing Machinery. [CrossRef]

- Bouhsine, Taha. 2024. Deep learning 2.0: Artificial neurons that matter – reject correlation, embrace orthogonality.

- Bouhsine, Taha, Imad El Aaroussi, Atik Faysal, and Wang. 2024. Simo loss: Anchor-free contrastive loss for fine-grained supervised contrastive learning. In Submitted to The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations. under review.

- Cortes, Corinna. 1995. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning. [CrossRef]

- Cybenko, George. 1989. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Mathematics of control, signals and systems 2(4), 303–314. [CrossRef]

- de Coulomb, Charles-Augustin. 1785. Premier mémoire sur l’électricité et le magnétisme. Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, 1–31. in French.

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. 2021. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale.

- Draganov, Andrew, Sharvaree Vadgama, and Erik J Bekkers. 2024. The hidden pitfalls of the cosine similarity loss. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.16468.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich. 1835. Allgemeine Lehrsätze in Beziehung auf die im verkehrten Verhältniss des Quadrats der Entfernung wirkenden Anziehungs- und Abstossungskräfte. Göttingen: Dietrich.

- Goodfellow, Ian, Yoshua Bengio, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. 2016. Deep learning, Volume 1. MIT Press.

- Hornik, Kurt, Maxwell B. Stinchcombe, and Halbert L. White. 1989. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Networks 2, 359–366. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Changcun. 2020. Relu networks are universal approximators via piecewise linear or constant functions. Neural Computation 32(11), 2249–2278. [CrossRef]

- Ivakhnenko, Alexey Grigorevich. 1971. Polynomial theory of complex systems. IEEE transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (4), 364–378. [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, Paul. 1901. Étude comparative de la distribution florale dans une portion des alpes et des jura. Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles 37, 547–579.

- Jacot, Arthur, Franck Gabriel, and Clément Hongler. 2018. Neural tangent kernel: Convergence and generalization in neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 31.

- Kepler, Johannes. 1939. Ad vitellionem paralipomena, quibus astronomiae pars optica traditur. 1604. Johannes Kepler: Gesammelte Werke, Ed. Walther von Dyck and Max Caspar, Münchenk.

- Knoll, Glenn F. 2010. Radiation Detection and Measurement (4 ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Lecun, Y., L. Bottou, Y. Bengio, and P. Haffner. 1998. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 86(11), 2278–2324. [CrossRef]

- Lee-Thorp, James, Joshua Ainslie, Ilya Eckstein, and Santiago Ontanon. 2022, May. FNet: Mixing Tokens with Fourier Transforms. arXiv:2105.03824 [cs].

- Liu, Hanxiao, Zihang Dai, David R. So, and Quoc V. Le. 2021, June. Pay Attention to MLPs. arXiv:2105.08050 [cs].

- Livni, Roi, Shai Shalev-Shwartz, and Ohad Shamir. 2014. An algorithm for training polynomial networks.

- Lu, Zhou, Hongming Pu, Feicheng Wang, Zhiqiang Hu, and Liwei Wang. 2017. The expressive power of neural networks: A view from the width. Advances in neural information processing systems 30.

- Modest, Michael F. 2013. Radiative Heat Transfer (3 ed.). New York: Academic Press.

- Montavon, Grégoire, Wojciech Samek, and Klaus-Robert Müller. 2018, February. Methods for interpreting and understanding deep neural networks. Digital Signal Processing 73, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Nair, Vinod and Geoffrey E Hinton. 2010. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the 27th international conference on machine learning (ICML-10), pp. 807–814.

- Newton, Isaac. 1687. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. London: S. Pepys.

- Ng, Andrew, Michael Jordan, and Yair Weiss. 2001. On spectral clustering: Analysis and an algorithm. Advances in neural information processing systems 14.

- Rahimi, Ali and Benjamin Recht. 2007. Random features for large-scale kernel machines. Advances in neural information processing systems 20.

- Rappaport, Theodore S. 2002. Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice (2 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Rea, Mark S. 2000. The IESNA Lighting Handbook: Reference & Application (9 ed.). New York: Illuminating Engineering Society of North America.

- Schölkopf, Bernhard, John C Platt, John Shawe-Taylor, Alex J Smola, and Robert C Williamson. 2001. Estimating the support of a high-dimensional distribution. Neural computation 13(7), 1443–1471. [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, Bernhard, Alexander Smola, and Klaus-Robert Müller. 1997. Kernel principal component analysis. In International conference on artificial neural networks, pp. 583–588. Springer.

- Schölkopf, Bernhard, Alexander Smola, and Klaus-Robert Müller. 1998. Nonlinear component analysis as a kernel eigenvalue problem. Neural computation 10(5), 1299–1319. [CrossRef]

- Skolnik, Merrill I. 2008. Radar Handbook (3 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Steck, Harald, Chaitanya Ekanadham, and Nathan Kallus. 2024. Is cosine-similarity of embeddings really about similarity? In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, pp. 887–890.

- Tanimoto, Taffee T. 1958. Elementary mathematical theory of classification and prediction.

- Tolstikhin, Ilya, Neil Houlsby, Alexander Kolesnikov, Lucas Beyer, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Jessica Yung, Daniel Keysers, Jakob Uszkoreit, Mario Lucic, and Alexey Dosovitskiy. 2021. Mlp-mixer: An all-mlp architecture for vision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.01601.

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 30.

- Williams, Christopher and Matthias Seeger. 2000. Using the nyström method to speed up kernel machines. Advances in neural information processing systems 13.

- Williams, Christopher KI and Carl Edward Rasmussen. 2006. Gaussian processes for machine learning, Volume 2. MIT press Cambridge, MA.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).