1. Introduction

Melanoma is one of the deadliest forms of skin cancer, but early detection significantly improves the chances of successful treatment. According to the U.S. National Cancer Institute, the 5-year survival rate for patients diagnosed at localized stages (0, I, II) is as high as 97.6%. In contrast, survival rates decrease sharply to 60.3% when diagnosed at a regional stage (III) and drop further to 16.2% at the metastatic stage (IV) [

1]. These statistics highlight the importance of melanoma diagnosis in the early stages.

Recent advances in deep learning have accelerated the development of automated methods for skin lesion diagnosis, leading to a growing number of AI models designed specifically for dermatology. The availability of relatively large, publicly accessible skin lesion datasets has further propelled progress in this field, enabling the refinement of deep-learning-based diagnostic approaches. The adoption of such automated systems for melanoma detection holds significant potential for improving early diagnosis and, consequently, enhancing patient survival rates.

Despite recent progress, existing lesion analysis methods face several limitations. First, the majority of datasets suffer from the lack of detailed metadata from pathology reports such as Breslow thickness, presence of ulceration, regression, dermal mitotic rate, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, preexisting nevus, steatosis, perivascular and perineural invasion, making it difficult to assess how well these methods perform, especially on early-stage lesions. Specifically, Breslow thickness and ulceration determine the T-category in the TNM classification used for disease staging. Without this information, the distribution of early/advanced melanomas remains unknown. Since early detection of melanoma is a primary objective of deep learning models, the lack of dedicated datasets makes it difficult to assess their effectiveness accurately. This gap poses a significant challenge to the development of reliable diagnostic tools, as early-stage melanoma can exhibit visual similarities to benign nevi, borderline lesions, melanosis, or even scars [

2]. These variations in appearance across stages could pose a challenge for deep learning models, potentially affecting classification performance. Additionally, early-stage melanoma often exhibits subtle features, making it more challenging to differentiate from benign lesions and complicating accurate diagnosis. As a result, an imbalanced distribution of melanoma stages in datasets can introduce bias into deep learning models. When trained on data with unknown stage distribution, models may not effectively address early detection, presumably failing to identify early-stage melanoma accurately.

Secondly, the wide availability of large open-access datasets presents a challenge, as nearly all research projects rely on the same training data, while cross-dataset evaluation remains vastly underutilized. For example, only 36 of 176 skin lesion segmentation methods studied in [

3] used cross-dataset evaluation to test their models. Moreover, only 23.6% of works studied in [

4] used an external dataset for evaluation. Without testing across diverse datasets, it’s challenging to determine whether a method will perform robustly in real-world clinical settings.

Assessing the performance of deep learning models is a critical medical and legal concern, prompting the curation of specialized datasets for this purpose. Researchers can use general benchmarks to evaluate the robustness of deep learning models [

5]. Additionally, specialized skin lesion analysis datasets exist, such as skin tone diversity benchmarks for lesion diagnosis [

6,

7] and datasets that categorize images by Breslow thickness bins rather than providing exact values [

8]. While there are multiple datasets containing skin lesion images, it is not a common practice that models are tested with multiple datasets from different sources, and no further analysis of the bias and robustness of the models is provided [

4].

We propose an early-stage melanoma benchmark dataset (EMB) consisting of melanoma images with Breslow thickness and T-category. Data was collected from known public sources and delivered in a standardized format for future use. We also present a detailed evaluation of multiple models on the curated dataset. Our results confirm that models perform worse on a dataset composed of thin melanoma images compared to their performance on a dataset with an unknown stage distribution. The EMB dataset addresses the gaps described above as it provides labeled images with an emphasis on early-stage melanoma and is designed to facilitate cross-dataset benchmarking, offering a new standard for assessing the reliability and accuracy of automated melanoma diagnostic tools. The dataset and code used to prepare the data are available at

GitHub

2. Methods

The early-stage melanoma benchmark dataset was developed to support research on automated melanoma diagnosis with a particular focus on early detection. It consists of melanoma images paired with corresponding thickness information provided in millimeters. The thickness data was extracted from image descriptions or metadata found in archival sources. Each lesion was categorized into a T-category label based on its thickness.

2.1. Data Collection

Images for the datasets came from two publicly available repositories: the ISIC Archive [

9] and the Dermoscopy Atlas website [

10]. From the ISIC Archive, images with a melanoma thickness label and images from the category melanoma in situ were downloaded with corresponding metadata using the provided interface. The rest of the data was scraped from the Dermoscopy Atlas website. For scraped images, the thickness label was extracted from the image description or the assigned diagnosis of melanoma in situ. Initially, we collected 1290 images with matching Breslow thickness.

2.2. T-category Label

Online image repositories are based on community contribution, which causes the issue of potentially duplicated images appearing in the same repository and the same image being present in multiple repositories. Possible overlap between our data and the datasets commonly used for training was also assessed. Most skin lesion diagnosis methods were trained on ISIC datasets from the years 2016-2020 [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], so we removed overlapping images between our benchmark dataset and ISIC challenge datasets to ensure a fair comparison.

Following [

17], we found duplicates using the

czkawka [

18] application that compares image hashes using hamming distance to find identical and similar images. The search was performed using the Lanczos3 resize algorithm and gradient type hashes of size 16. The similarity threshold was set to 40 to find images with even minimal resemblance. All flagged duplicates were manually investigated to exclude false positives. We do not consider multiple images of the same lesion as duplicates. We began by identifying duplicate images within the collected dataset, where we found and removed 7 identical images. Next, we searched for duplicates between the ISIC Challenges and our benchmark datasets. Initially, this search was based on ISIC IDs, which led to identifying and removing 146 duplicate images. Additionally, using the

czkawka tool, we detected 33 more duplicate images with different ISIC IDs.

Currently, melanoma stages are defined based on metrics proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) using, among others, lesion thicknesses [

19]. We assigned the labels based on the T-grouping of the AJCC staging method. Breslov thickness indicates tumor thickness from the granular layer of the epidermis to the deepest level of invasion [

19]. We assigned T-category labels based on thickness information according to the

Table 1. We grouped the a and b categories together as we did not have ulceration information to distinguish them.

Figure 1 presents the final composition of the dataset. A total of 1104 images with thickness information were collected. Of these, 907 images came from the ISIC archive, and 197 were obtained through web scraping from the Dermoscopy Atlas website. The dataset includes 1017 dermoscopic images and 87 clinical photographs. Atlas data did not include the image type, so we labeled it based on visual characteristics observed in the data.

3. Results

To establish benchmark results on the EMB dataset, we tested various methods with code and model weights available online. We tested EfficientNet Ensemble, the winner of the SIIM-ISIC challenge in 2020 [

20], Class-Enhancement Contrastive Learning for Long-tailed Skin Lesion Classification (ECL) [

21], and deep mask pixel-wise supervision (DMP) [

22]. All methods were trained on data from the ISIC challenge datasets without external data. These methods were selected based on the public availability of the code, trained models, and demonstration of SOTA performance. Clinical images were excluded from testing as the methods were trained on dermoscopic images only. For the ISIC 2020 winner, we tested individual models from the ensemble, selecting only those that did not utilize metadata. For ECL, we tested two versions of the model: the 8-class model and the 9-class model. Similarly, for deep pixel-wise supervision, we tested the ConvNeXt 9-class models and the 2-class models. Input images for each model were preprocessed according to the specific requirements described in the original papers. Classification accuracy was assessed by checking whether the model correctly predicted the melanoma/malignant class. Since our dataset contains only melanoma cases, all images should be classified as either the positive class in binary models or the melanoma category in multi-class models.

Results achieved by tested models are shown in

Table 2. Column

All shows results for the entire dataset, and Columns

Tis-T4 provide results for lesions in the corresponding thickness stages. Column

Rep. shows the average accuracy reported by the authors on the ISIC dataset on which the model was tested.

All tested algorithms performed well on the datasets they were originally trained and evaluated on, but exhibited a significant drop in performance when tested on our dataset. The best-performing model from the ISIC winner ensemble (EfficientNet-B4 768 9c) reached an accuracy of 97.71% on the combined data from ISIC 2018-2020. However, when evaluated on our data, it achieved a median accuracy of 0.54 with a 95% confidence interval of . Similarly, the ECL 9 class model, which achieved an average accuracy of 86.11% on the ISIC 2019 test, showed a reduced accuracy of 0.40 (confidence interval ) on EMB data. The deep mask pixel-wise supervision (ConvNeXt-DMP 224 2c) achieved 90.70% accuracy on ISIC 2019+2020 data, and on EMB, its accuracy declined to 0.55 with a confidence interval of . All models showed the lowest accuracy on in situ and T1 melanomas, indicating difficulty in detecting early-stage lesions. Performance generally improved with increasing thickness, with T3 and T4 melanomas yielding the highest accuracy for most models, although some achieved their best results on T2 cases.

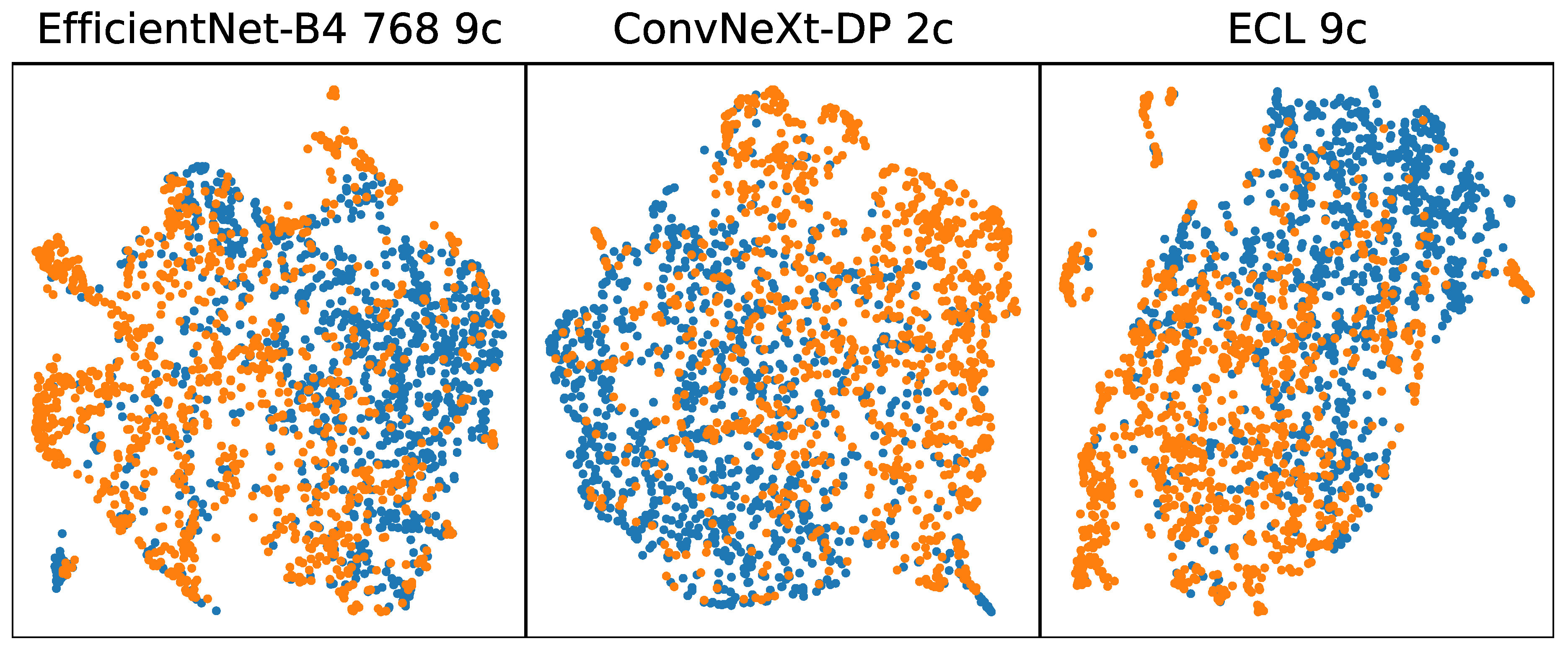

Figure 2 shows a UMAP visualization of features extracted from melanoma images from the ISIC 2019 dataset (blue) and from EMB (orange). The visualization reveals a relatively uniform structure in feature representation for both datasets, yet a non-uniformity exists between the challenge data and the benchmark data. This indicates that while early-stage melanoma shares some common features with later-stage melanoma, these shared features are insufficient for accurate classification when using models trained on the ISIC Challenge datasets.

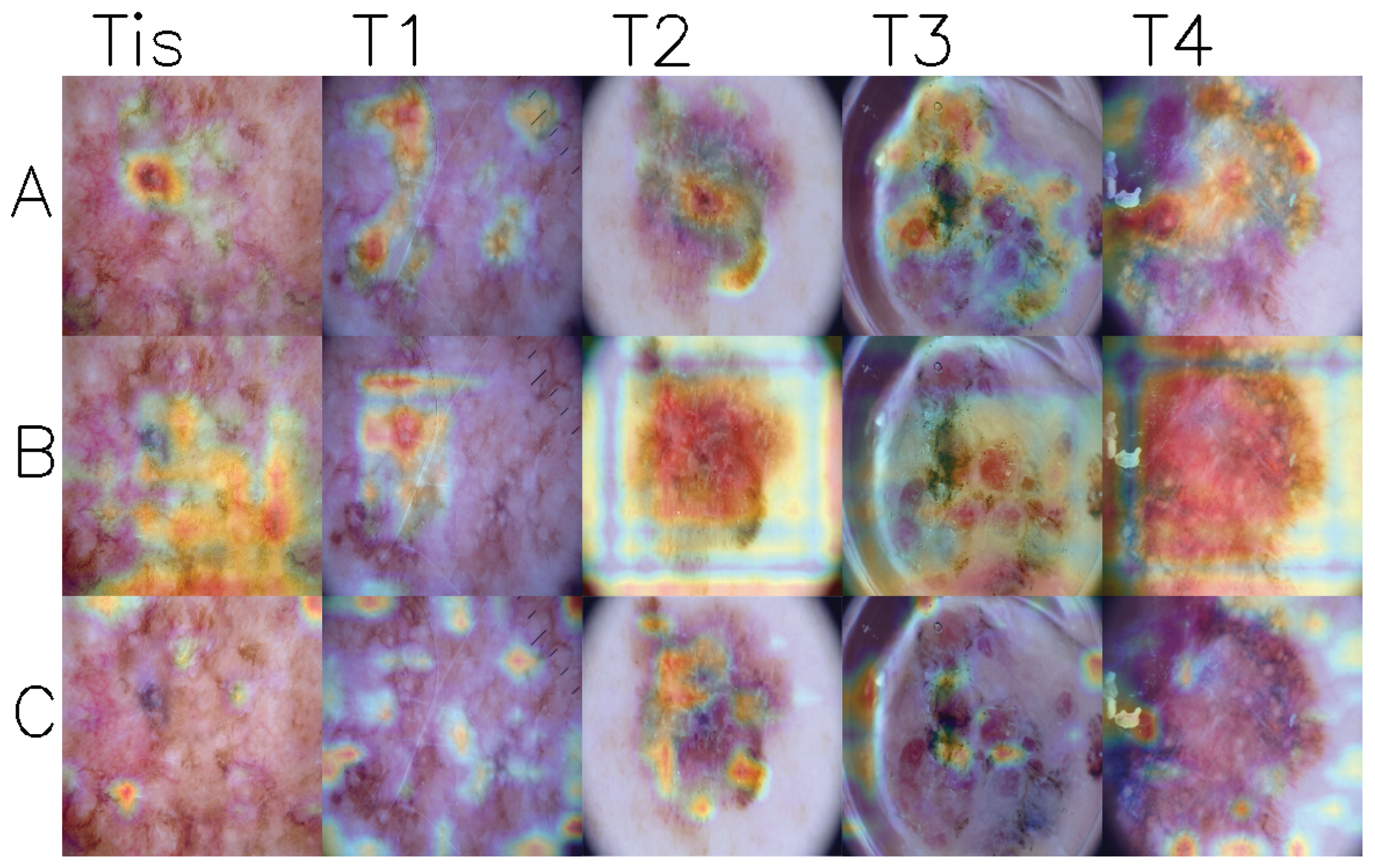

Figure 3 shows GradCam visualizations of activation maps from the last convolutional layer for three models. Upon examining the images, it can be observed that models generally focus on the lesion areas, particularly in stages T2 to T4. However, in stages Tis and T1 cases, the models often concentrate on seemingly unrelated regions while ignoring areas with high pigmentation.

4. Limitations

While our dataset serves as a benchmark for early melanoma diagnosis, several limitations should be considered. Although efforts were made to separate the benchmark dataset from the ISIC Challenge sets, some overlap may remain. Certain images in the benchmark dataset may appear in training sets if they originate from the ISIC Archive. This could affect benchmarking reliability, as models might previously be exposed to similar data in the training and validation stages. In addition, the dataset contains a higher representation of thin and in situ melanoma cases compared to more advanced stages. There is also a larger proportion of dermoscopic images relative to clinical images. The dataset prioritizes early intervention research, so we did not concentrate on balancing the dataset but rather on providing the highest possible number of melanoma images.

5. Conclusions

Deep learning algorithms have been developed to support non-dermatologist clinicians or assist in identifying suspicious lesions prior to clinical care. While significant progress has been made in this field, several key challenges remain unresolved. Our analysis highlights the following issues for deep learning algorithms in detecting malignant melanoma: (1) State-of-the-art algorithms exhibit significantly worse performance on in situ and T1 melanoma images compared to their reported performance on the ISIC Challenge dataset; (2) This results in a substantial drop in performance when evaluated on EMB dataset, which includes mainly early-stage melanoma; (3) Clinical images pose a notable challenge for the tested models, further impacting their effectiveness. A lack of diversity in the training data causes those problems. The unknown distribution of melanoma stages and the underrepresentation of early-stage lesions in commonly used datasets introduce biases, leading to early-stage melanoma often being misclassified as benign. Most of the currently developed models use the same data for training and rarely perform a cross-dataset evaluation of model performance. Addressing these challenges is crucial for developing more robust and reliable deep learning systems for melanoma detection, and our dataset provides a valuable resource to help tackle these issues by enabling T-category-specific analysis and cross-dataset evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and P.G.; methodology, A.D., P.G., and P.P.; software, A.D.; validation, A.D.; formal analysis, A.D., P.P., and P.G.; investigation, A.D., P.P., and P.G.; resources, A.D.; data curation, A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, R.P., P.P., and P.G.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, R.P. and P.G.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study presented in this paper was funded by Warsaw University of Technology, within the program Excellence Initiative: Research University, project “Diagnosis of skin cancer in the conditions of limited social mobility”, IDUB against COVID-19 call.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data and code used in this study are available at:

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ISIC |

The International Skin Imaging Collaboration |

| UMAP |

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction |

| EMB |

Early Melanoma Benchmark |

| GradCam |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| DMP |

Deep Mask Pixel-wise Supervision |

| ECL |

Class-Enhancement Contrastive Learning for Long-tailed Skin Lesion Classification |

References

- Five-Year Survival Rates | SEER Training.

- Ferrara, G.; Argenziano, G. The WHO 2018 Classification of Cutaneous Melanocytic Neoplasms: Suggestions From Routine Practice. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 675296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirikharaji, Z.; Barata, C.; Abhishek, K.; Bissoto, A.; Avila, S.; Valle, E.; Celebi, M.E.; Hamarneh, G. A Survey on Deep Learning for Skin Lesion Segmentation, 2022, [2206.00356 [cs, eess]].

- Daneshjou, R.; Smith, M.P.; Sun, M.D.; Rotemberg, V.; Zou, J. Lack of Transparency and Potential Bias in Artificial Intelligence Data Sets and Algorithms: A Scoping Review. JAMA Dermatology 2021, 157, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrycks, D.; Dietterich, T. Benchmarking Neural Network Robustness to Common Corruptions and Perturbations, [1903.12261 [cs]].

- Groh, M.; Harris, C.; Soenksen, L.; Lau, F.; Han, R.; Kim, A.; Koochek, A.; Badri, O. Evaluating Deep Neural Networks Trained on Clinical Images in Dermatology with the Fitzpatrick 17k Dataset, [2104.09957 [cs]].

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Liang, W.; Rotemberg, V.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Bailey, E.E.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Science Advances 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, J.; Daneshvar, S.; Argenziano, G.; Hamarneh, G. Seven-Point Checklist and Skin Lesion Classification Using Multitask Multimodal Neural Nets. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISIC Archive.

- Dermoscopy Atlas | Home.

- Gutman, D.; Codella, N.C.F.; Celebi, E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.; Mishra, N.; Halpern, A. Skin Lesion Analysis toward Melanoma Detection: A Challenge at the International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 2016, hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC), [1605.01397 [cs]].

- Codella, N.C.F.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection: A Challenge at the 2017 International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC), [1710.05006 [cs]].

- Codella, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Tschandl, P.; Celebi, M.E.; Dusza, S.; Gutman, D.; Helba, B.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Marchetti, M.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC), [1902.03368 [cs]].

- Combalia, M.; Codella, N.C.F.; Rotemberg, V.; Helba, B.; Vilaplana, V.; Reiter, O.; Carrera, C.; Barreiro, A.; Halpern, A.C.; Puig, S.; et al. BCN20000: Dermoscopic Lesions in the Wild, [1908.02288 [cs, eess]].

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Scientific Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The ISIC 2020 Challenge Dataset.

- Cassidy, B.; Kendrick, C.; Brodzicki, A.; Jaworek-Korjakowska, J.; Yap, M.H. Analysis of the ISIC image datasets: Usage, benchmarks and recommendations. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 75, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikrut, R. qarmin/czkawka, 2024. original-date: 2020-09-01T17:37:29Z.

- Keung, E.Z.; Gershenwald, J.E. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert review of anticancer therapy 2018, 18, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Q.; Liu, B.; Liu, F. Identifying Melanoma Images using EfficientNet Ensemble: Winning Solution to the SIIM-ISIC Melanoma Classification Challenge, [2010.05351 [cs]].

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, K.; Xie, F. ECL: Class-Enhancement Contrastive Learning for Long-tailed Skin Lesion Classification, 2023, [2307.04136 [cs]].

- Dzieniszewska, A.; Garbat, P.; Piramidowicz, R. Deep Pixel-Wise Supervision for Skin Lesion Classification. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2025, 193, 110352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).