1. Introduction

Melanoma is a malignant tumor originating from melanocytes, the neural crest derived cells responsible for melanin production in the epidermis. Unlike non-melanoma skin cancers, melanoma exhibits a high propensity for early invasion and metastasis, making it one of the most lethal forms of skin cancer despite its relatively low incidence rate [

1].

The pathogenesis of melanoma is driven by a combination of environmental exposures and genetic alterations. Among the most prominent driver mutations are activating alterations in the BRAF gene, particularly the V600E mutation, present in approximately 40-60% of cutaneous melanomas, as well as NRAS (15-20%) and NF1 mutations (10-15%) [

1,

2,

3]. These mutations activate the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, promoting uncontrolled cell proliferation, survival, and migration. In addition, inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor genes like CDKN2A contribute to melanoma progression [

4,

5]. Intermittent intense sun exposure and other ultraviolet radiation sources induce DNA damage and mutagenesis, acting as a primary environmental initiator in susceptible individuals [

6].

Globally, the incidence of melanoma has been rising, especially in fair-skinned populations. According to international epidemiological data, melanoma accounts for approximately 1-2% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide, with over 325,000 new cases and 57,000 deaths annually [

7]. It ranks as one of the top five cancers in countries with high UV exposure, such as Australia, New Zealand, and parts of North America and Europe. The increased incidence among younger individuals, together with the increased cost of advanced immunotherapies and targeted treatments, further amplifies the global challenge of melanoma [

8,

9].

Clinically, melanoma often resembles benign melanocytic lesions such as nevi, which complicates early detection. Variants like dysplastic, Spitz, or deep penetrating nevi share dermoscopic and histopathologic features with early melanomas, contributing to diagnostic ambiguity [

10,

11]. This overlap frequently results in delayed or missed diagnoses, especially in early-stage tumors lacking overt asymmetry or pigment irregularity.

Early-stage detection improves prognosis. Localized melanomas have a 5-year survival rate exceeding 98%, whereas metastatic melanoma carries a survival rate below 30% despite modern therapies [

1]. Thus, enhancing early diagnostic accuracy remains a priority for reducing melanoma-related mortality. Advances in digital pathology, molecular biomarkers, and AI-assisted dermoscopy are being investigated to improve differentiation between benign and malignant lesions [

4,

12].

Among AI-assisted tools, convolutional neural networks (CNN) have been reported to have good performance in classifying skin lesions with accuracy comparable to or exceeding that of dermatologists [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. CNNs process dermoscopic images to identify subtle malignancy indicators such as asymmetry, border irregularity, color variation, and diameter [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Transfer learning is frequently utilized in this domain, where models pre-trained on large datasets like ImageNet are fine-tuned on smaller, domain-specific datasets such as skin lesion images [

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, CNNs encounter challenges in ensuring generalizability across diverse populations and imaging conditions. Besides, their reliance on fixed-size square images (e.g., 224×224, 299×299, 331×331 pixels) can lead to the loss of relevant details in high-resolution dermoscopic images.

To overcome these limitations, Vision Transformers (ViT) have emerged as a viable alternative for image classification tasks [

27]. They implement self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and contextual information, thereby improving performance on complex visual tasks such as melanoma detection [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Unlike CNNs, which rely on local receptive fields, ViTs model global relationships between image patches, making them effective for analyzing the heterogeneous features of skin lesions. Recent studies indicate that ViTs surpass CNNs on various medical imaging benchmarks, including dermatology datasets [

28,

31,

32].

However, ViTs typically require large amounts of training data due to their high parameter count and the absence of inductive biases found in CNNs. This demand creates challenges in medical domains where annotated datasets are often limited. Although large datasets for skin lesions are publicly available, such as the ISIC archive [

33], the number of images, which is on the order of tens of thousands, remains small compared with datasets like ImageNet that contain millions of instances. To address this limitation, data augmentation techniques can be applied, for example by using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to generate synthetic images or by applying self-supervised learning to make use of unlabeled data [

34,

35,

36]. In addition, transfer learning from large-scale pre-trained ViT models offers a practical strategy to reduce the impact of data scarcity.

A pretrained ViT model is evaluated in this study to classify dermoscopic images into benign and malignant categories. The model is trained and fine-tuned on the ISIC 2019 dataset, which offers a large collection of high-quality dermoscopic images with expert-provided annotations. To improve the training process, a GAN-based data augmentation pipeline is introduced, generating synthetic images that strengthen the model’s generalization capabilities.

The performance of the resulting model was assessed on a new dataset with data from hospitals in the United States. The images in this dataset received initial classifications from the FotoFinder AI MoleAnalyzer Pro, a commercial diagnostic tool, and were later confirmed by biopsy. The FotoFinder system is a well-established instrument in the domain of skin lesion image classification, as documented in several studies [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The proposed method, based on a Vision Transformer architecture, achieved a statistically significant increase in classification accuracy compared to the commercial tool and convolutional neural network baselines. This outcome demonstrates the utility of transformer-based models for improving melanoma detection.

This article is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the experimental setup, including datasets, model architectures, training, augmentation, and evaluation.

Section 3 presents the performance results, statistical tests, and the effect of synthetic data on the performance of the evaluated models.

Section 4 provides a discussion of these findings, their architectural and clinical implications. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the work, acknowledges its limitations, and suggests future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Preparation

To train and evaluate the Vision Transformer model for melanoma classification, the ISIC 2019 Challenge dataset was used, an extensive repository of dermoscopic images compiled by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration [

45]. The dataset includes over 25,000 high-resolution images of skin lesions annotated by expert dermatologists. These images encompass a variety of skin conditions, such as benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and malignant melanomas, representing a spectrum of clinical presentations.

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets. ISIC provides a train/validation split, and the initial test set from ISIC-2019 was repurposed as the validation set. The training set included 12,875 nevus images and 4,522 melanoma images. The validation set included 2,495 nevus images and 1,327 melanoma images. Finally, the test set was constructed as a new subset consisting of 96 nevus images and 91 melanoma images.

The MN187 dataset consisted of 187 de-identified dermoscopic images obtained through a collaboration with the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital Dermatology Clinic. It included 96 benign nevi and 91 malignant melanomas, all biopsy confirmed. Each image was initially analyzed by the FotoFinder AI MoleAnalyzer Pro, which produced preliminary malignancy probability scores used for comparative evaluation.

The FotoFinder MoleAnalyzer Pro is a market-approved convolutional neural network. It was the first AI application for dermatology to receive approval in the European market [

43]. This deep learning system uses complex machine learning algorithms to analyze dermoscopic images and provide malignancy risk assessments with probability scores of

to

, where higher scores indicate a higher risk of malignancy [

38]. The system can identify melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and most squamous cell carcinomas, including actinic keratoses [

39].

Evaluations of the MoleAnalyzer Pro in multiple clinical studies have produced variable outcomes, influenced by the study setting and population. In controlled clinical environments, the system has been reported to have high diagnostic accuracy, with sensitivities from

to

and specificities from

to

[

42]. One prospective diagnostic accuracy study found a sensitivity of

and specificity of

, with performance similar to that of expert dermatologists [

41]. Another study found the AI’s diagnostic accuracy was similar to experienced dermatologists, achieving an area under the ROC curve of

[

39].

In contrast, real-world clinical studies have reported more modest results. One study of a high-risk melanoma population found lower metrics, with a sensitivity of

and specificity of

compared to histopathology as ground truth (ROC-AUC of

) [

38]. Other research found even lower performance, with a sensitivity of

and specificity of

, and concluded that the system cannot take the place of dermatologist decision-making [

37].

For evaluating CNN models tried in this study, the images were resized and padded to a consistent size of 224x224 pixels, which is the input size required by most pre-trained CNN backbone architectures. Padding with black pixels was applied to make images square, which allows us to keep the original proportions of images within the padding and to eliminate distortions that could affect model performance. Scaling was performed to preserve significant features of the images. Although ViT models can handle variable input sizes, input dimensions were standardized across all models to enable fair comparisons.

2.2. Model Architecture

Modern deep learning classification models typically consist of a pretrained feature extraction backbone paired with a classification head composed of fully connected layers. The backbone, often a convolutional neural network or a transformer-based model, is trained on large datasets like ImageNet, while the classification head is fine-tuned for the specific task.

In this study, the Vision Transformer was chosen as the backbone architecture. ViTs represent a significant advancement in image classification by utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture global context. Introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017), attention mechanisms have revolutionized natural language processing and generative AI [

46]. Although initially developed for text data, this architecture has been successfully adapted for image analysis [

27].

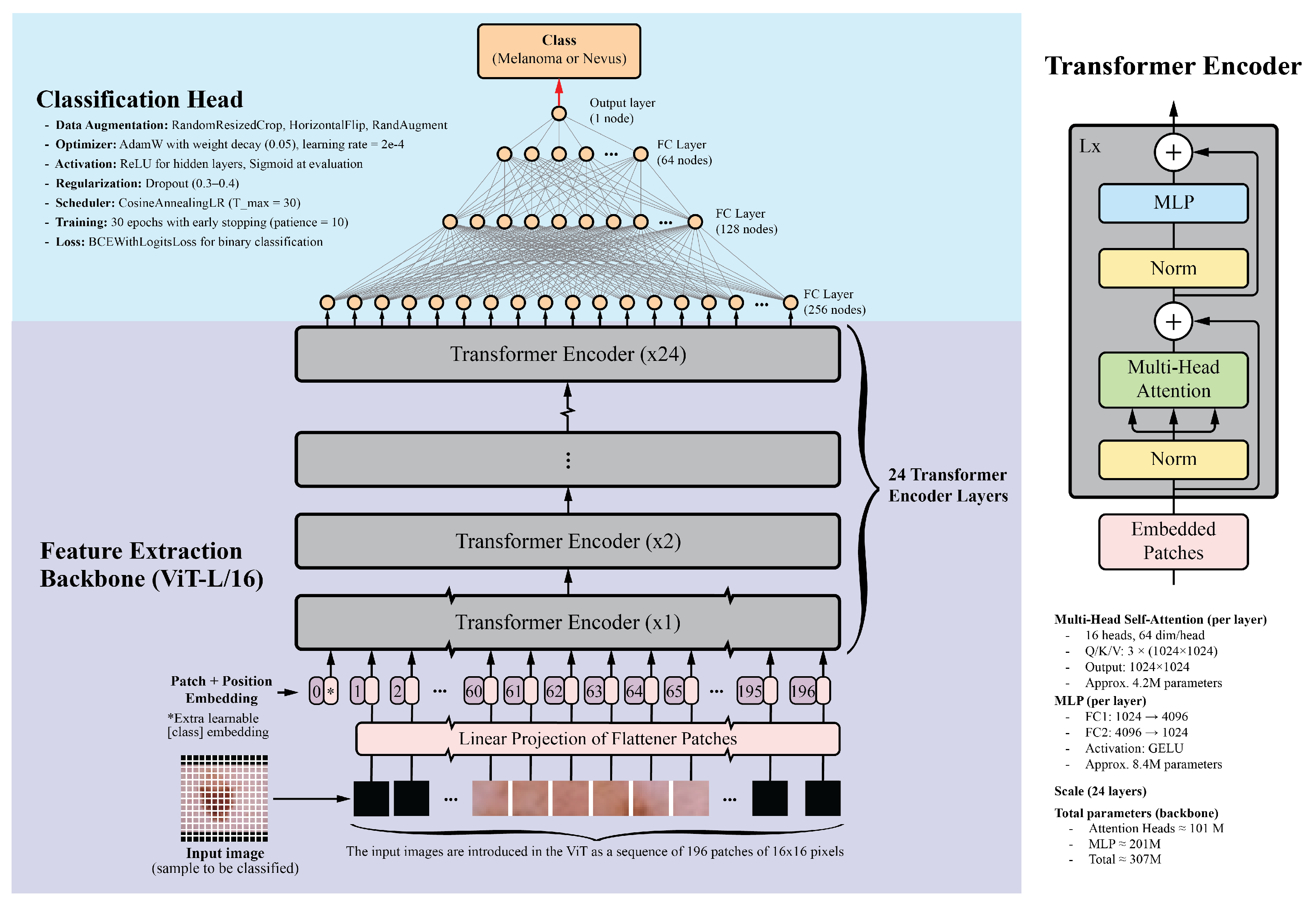

Unlike traditional CNNs that rely on local receptive fields, ViTs divide images into fixed-size patches, embed them linearly, and process them through transformer encoders. This enables ViTs to model long-range dependencies and complex relationships between image regions, making them effective for tasks requiring a holistic understanding. For this study, the ViT-L/16 model, pretrained on the ImageNet-1k dataset, was selected. This model, part of the PyTorch library, contains 24 transformer layers, each with 16 attention heads and a hidden size of 1024. Input images are divided into 16x16 pixel patches, resulting in a sequence of 196 patches for a standard 224x224 image. Each patch is embedded into a 1024-dimensional vector, with positional embeddings added to retain spatial information. The transformer layers include multi-head self-attention mechanisms, feed-forward neural networks, layer normalization, and residual connections. With approximately 307 million parameters, the detailed architecture of the ViT model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The classification head consists of four fully connected layers with ReLU activations: 256, 128, 64, and 1 neurons, respectively. The final layer uses a sigmoid activation function to generate a probability score between 0 and 1, indicating the probability of malignancy. Dropout layers with a 0.5 dropout rate were added after each fully connected layer to prevent overfitting. While the classification head was trained from scratch, the ViT backbone was fine-tuned on the skin lesion dataset.

For comparison, several CNN backbones were evaluated, including ResNet-152, DenseNet-201, EfficientNet-B7, and InceptionV4. These models, recognized as top performers in their respective families, have achieved good results in image classification tasks, including skin lesion analysis [

16,

47,

48,

49]. Additionally, the ViT-B/16 model, a smaller variant of the ViT-L/16, was included. This model features 12 transformer layers, 12 attention heads, and a hidden size of 768, while maintaining a similar architecture to that shown in

Figure 1. The classification head architecture was standardized across all models to ensure a fair comparison.

2.3. Training Configuration and Optimization

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch (version 2.8.0) and executed on a pair of NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPUs with 48 GB memory. For consistency among models, a unified training configuration was adopted. Images were normalized using the ImageNet mean and standard deviation ([0.485, 0.456, 0.406], [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]), in line with the pretrained weights. The training pipeline included random resized cropping to 224 pixels with a scale range of 0.7 to 1.0, random horizontal flipping, and RandAugment with two operations of magnitude 9. The training set was loaded with a batch size of 128 and shuffled at each epoch, while the validation and test sets were processed with batch sizes of 64 images.

The Vision Transformer backbone was initialized with ImageNet-1k pretrained weights. For stable training and reduced overfitting, the transformer backbone parameters were frozen, and only the classification head was trained. The classification head consisted of four fully connected layers with sizes 256, 128, 64, and 1 neuron. Each hidden layer included batch normalization, ReLU activations, and dropout with a rate of 0.5. The final output layer produced a raw logit for binary classification.

Training optimization used binary cross-entropy with logits (BCEWithLogitsLoss) as the loss function. Parameters were updated with the AdamW optimizer configured with a learning rate of and a weight decay of . A cosine annealing learning rate scheduler with progressively reduced the learning rate across epochs.

2.4. Data Augmentation

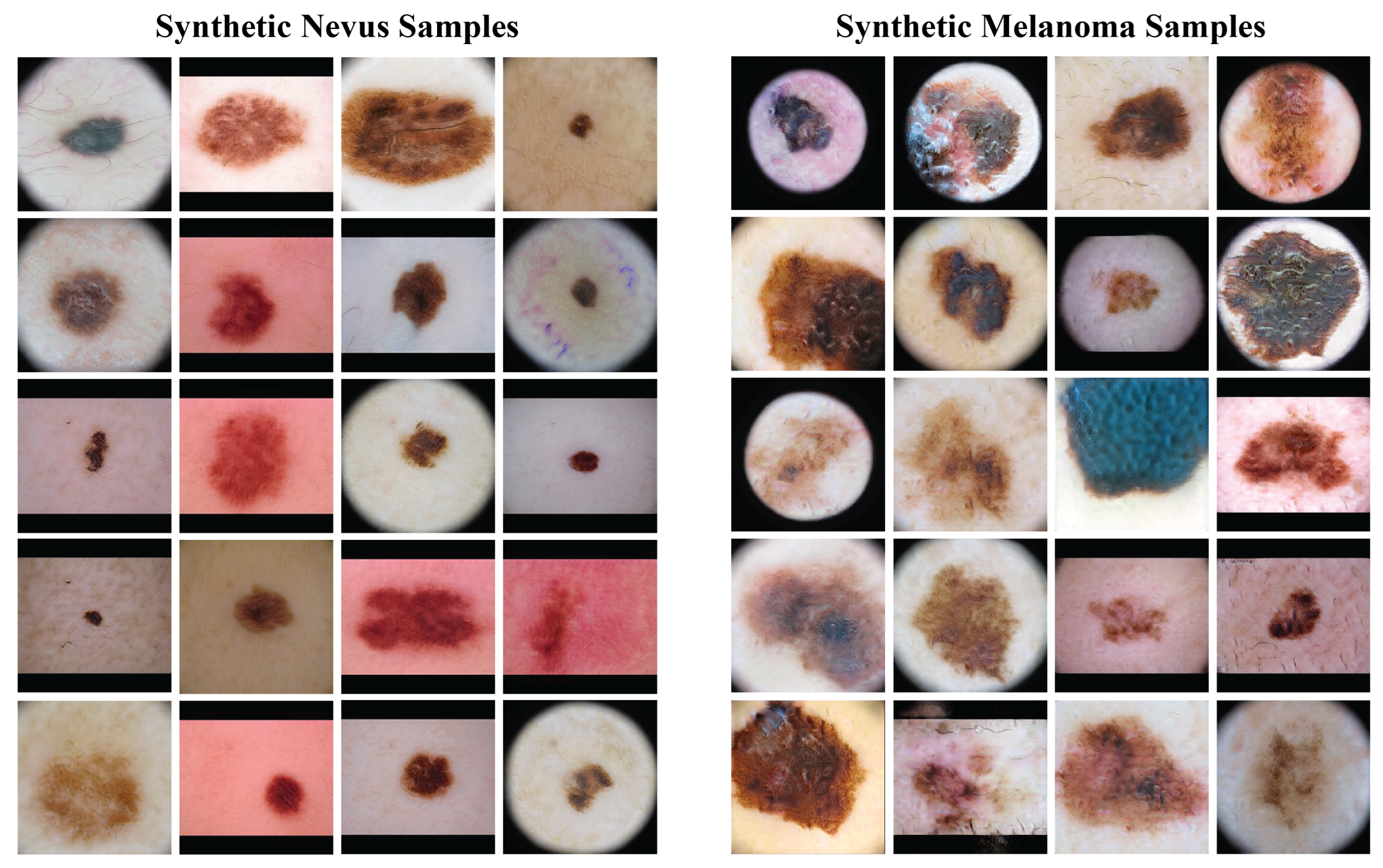

To address class imbalance and broaden the training distribution, generative models were applied to the ISIC 2019 challenge dataset, which contains 12,875 nevus and 4,522 melanoma images. Separate generative adversarial networks were trained for each class on images resized to pixels, allowing the networks to capture class-specific distributions.

The GAN models followed the StyleGAN2-ADA architecture described in [

50] and used the official NVIDIA implementation [

51], with modifications introduced for compatibility with newer PyTorch and CUDA versions. The StyleGAN2-ADA training procedure is based on

ticks, where each tick processes a fixed number of images. Training was conducted for 1000 ticks, with regular snapshots saved to monitor progress.

The FID50k_full metric, which calculates the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) over 50,000 generated images, served to monitor training progress. To manage computational expenses, training concluded manually once the FID score dropped below 50. Each GAN required several days to train.

After training, each GAN produced 25,000 images for its class, creating a total of 50,000 synthetic samples. These generated images maintained visual consistency with real dermoscopic data and contained variations within their class.

All synthetic images were resized and normalized to match the preprocessing of the real data ( pixels, normalized with ImageNet statistics). The combined set of real and generated images formed a larger and more balanced training dataset, which supported the classification model’s performance.

2.5. Model Performance Monitoring and Evaluation

The Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) serves as the primary evaluation metric in this study. This threshold-independent metric measures binary classification performance by quantifying the model’s capacity to separate positive and negative classes across all classification thresholds [

52,

53,

54]. ROC-AUC is appropriate for imbalanced datasets and finds common application in medical imaging tasks such as skin lesion classification.

A high ROC-AUC score alone does not fully characterize model performance. For instance, a model might obtain a high score by correctly ranking a small number of straightforward cases, which could overstate its general discriminative capability [

55].

To evaluate the statistical significance of performance differences, the ROC-AUC of each model is compared with a baseline model using DeLong’s test [

56]. This non-parametric test assesses the difference between two correlated ROC curves while considering the paired nature of predictions on the same dataset.

The statistical hypotheses are defined as follows: the null hypothesis () states no difference in ROC-AUC exists between the baseline model and the evaluated model (); the alternative hypothesis () states a difference exists (). A significance level of is used. A p-value from DeLong’s test less than () leads to rejection of the null hypothesis, supporting a statistically significant performance difference. If the null hypothesis is not rejected (), the observed AUC difference is considered likely due to chance and not a significant improvement over the baseline model.

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

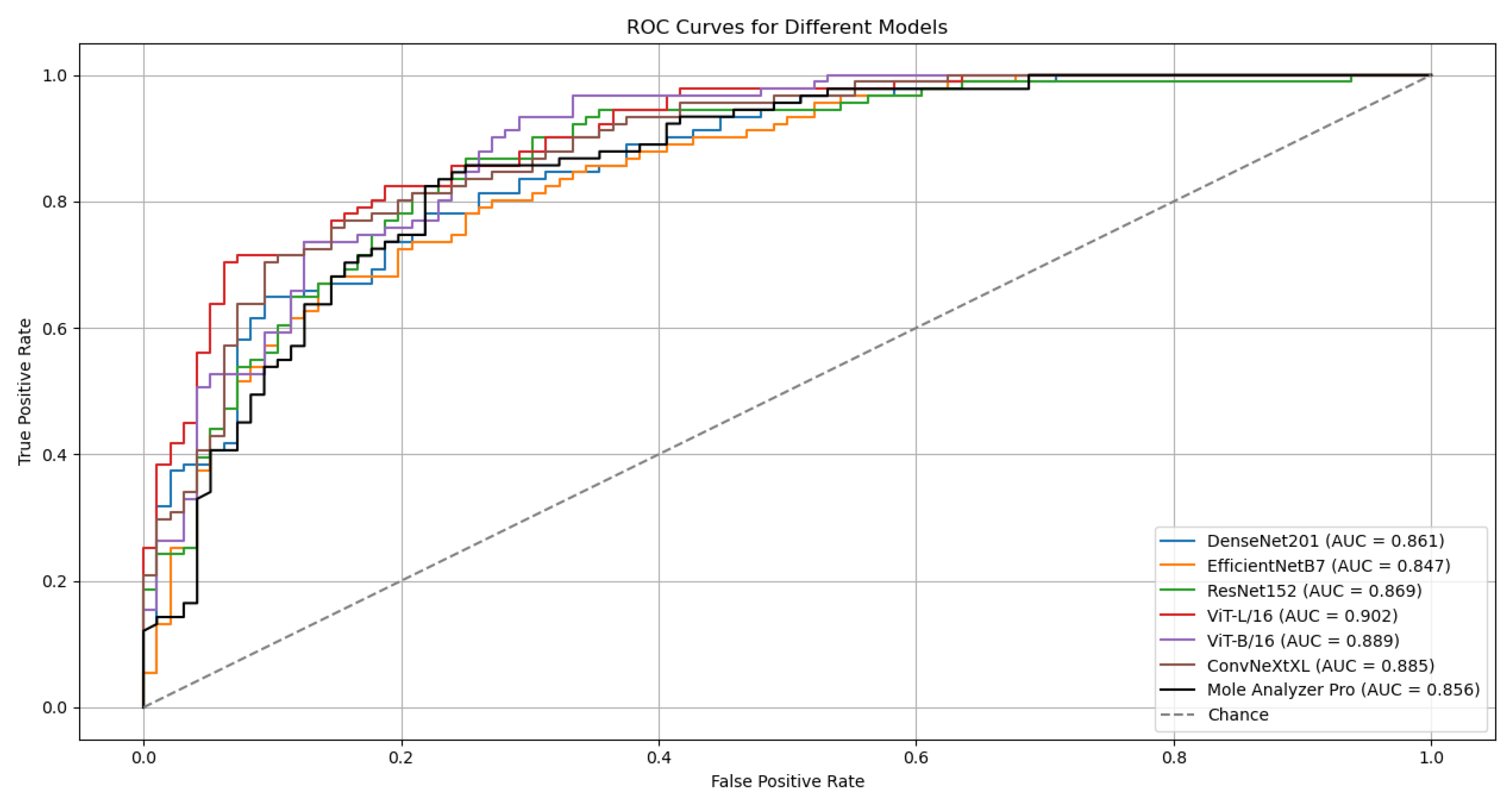

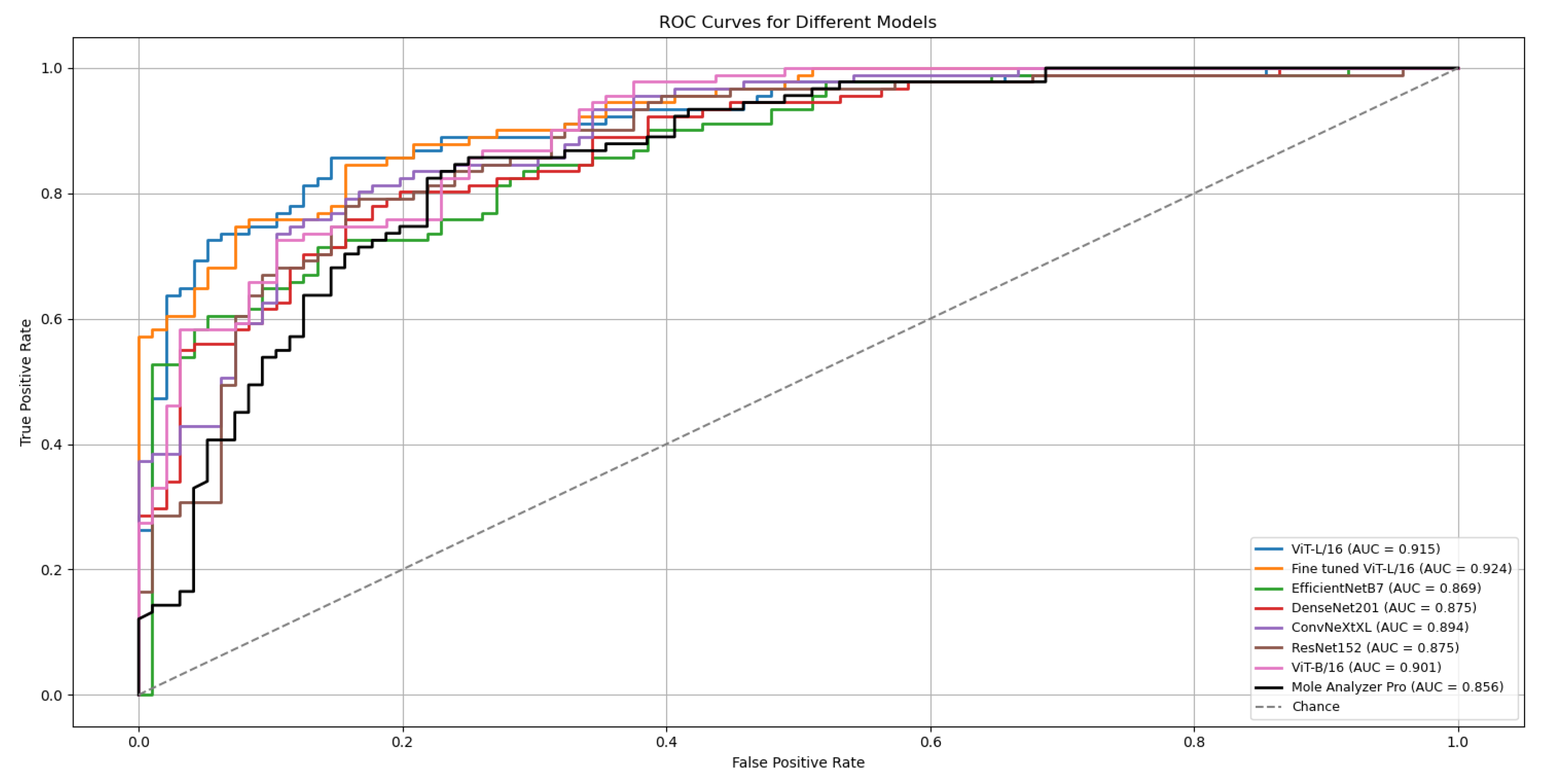

The proposed models were evaluated using the ROC-AUC metric.

Table 1 summarizes the results for five deep learning classification models, each employing distinct backbones for feature extraction while sharing the same classification head, as depicted in

Figure 1. These models were trained on the ISIC-19 dataset, using standard image transformations (Resize, CenterCrop, and Normalization) integrated into the training pipeline. Validation was performed on the ISIC-19 dataset, and testing was carried out on the MN187 dataset.

The outcomes of five runs for each model are detailed in

Table 1. The ROC Curves and AUC scores for the top-performing model, ViT-L/16, on both validation and test datasets are presented in

Figure 2.

Although the models were trained on the ISIC-19 dataset, they kept strong generalization capabilities when evaluated on the MN187 dataset, performing at a level similar to or exceeding the Mole Analyzer Pro. The ViT-L/16 model achieved the highest ROC-AUC score of 0.902 on the MN187 dataset, exceeding all other models. The ConvNeXt-XL, a CNN-based model larger than ViT-L/16 in terms of parameters, achieved the second-highest ROC-AUC score of 0.885, comparable to the ViT-B/16 model. The other CNN models had lower performance, aligning more closely with the Mole Analyzer Pro.

While most models achieved higher ROC-AUC scores than the Mole Analyzer Pro, it is necessary to assess whether these improvements are statistically significant.

Table 2 summarizes the results of DeLong’s test, which compares the ROC-AUC of each deep learning model to that of the Mole Analyzer Pro.

The ViT-L/16 model achieved a ROC-AUC of 0.901, which exceeds the Mole Analyzer Pro ROC-AUC of 0.856. However, the p-value of 0.070 means this difference is not statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level. The CNN models (EfficientNet-B7, DenseNet-201, ConvNeXt-XL) and the ViT-B/16 also had higher ROC-AUC scores than the Mole Analyzer Pro, but their p-values suggest these differences are not statistically significant. None of the models had a performance improvement that could be attributed to factors other than chance, so the null hypothesis could not be rejected.

3.2. Results with Data Augmentation

While models like ViT-L/16 and ConvNeXt-XL achieved higher ROC-AUC scores and lower probabilities of the differences being due to chance, they did not reach a statistically significant improvement over the Mole Analyzer Pro. Vision Transformers, due to their high parameter count and lack of inherent CNN inductive biases, often need large volumes of training data for optimal performance.

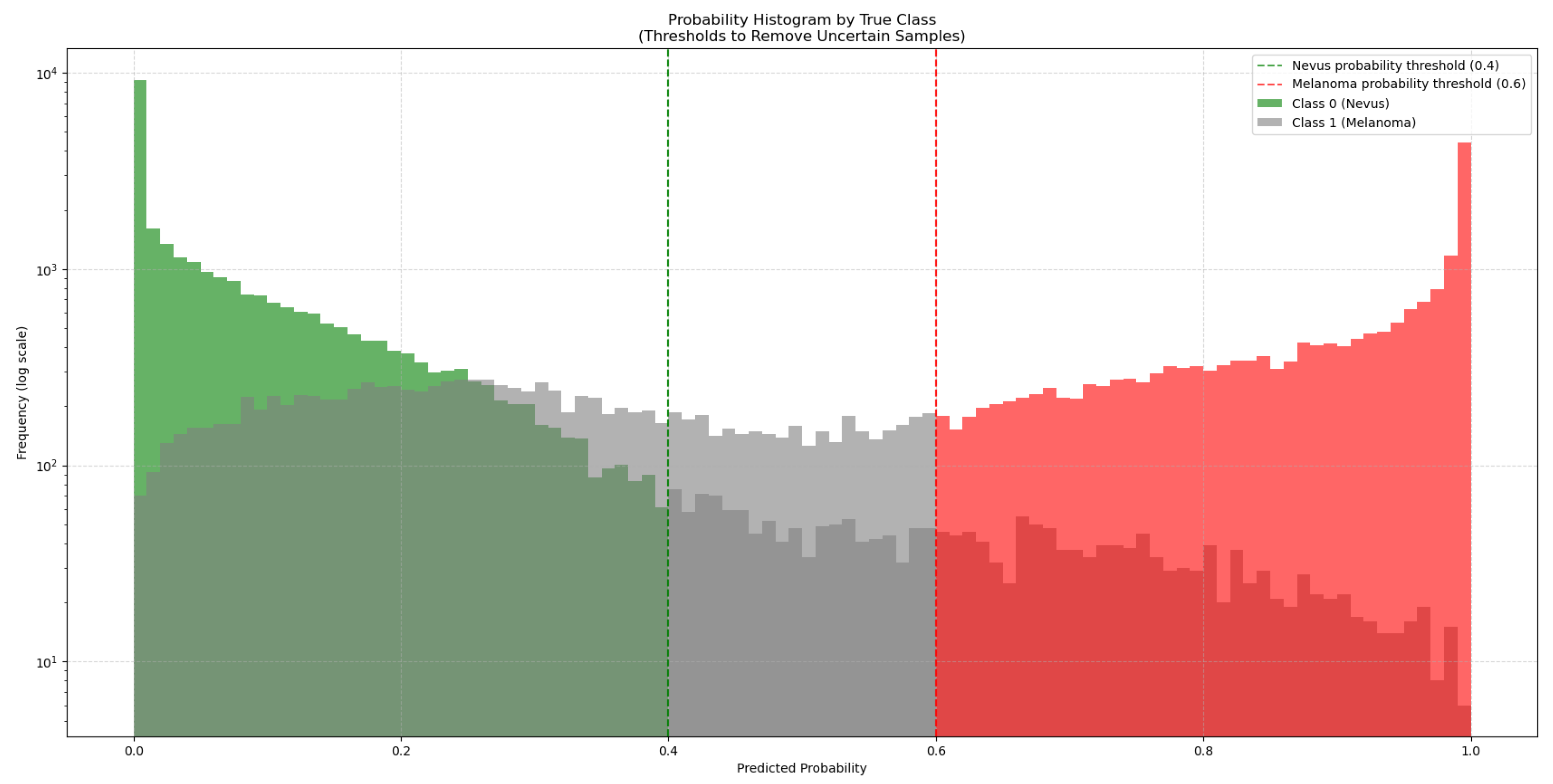

To address this, 50,000 synthetic images generated with GANs were added to the training dataset. As these synthetic images come from a trained GAN model, they might not match the true data distribution perfectly and could contain artifacts or biases. To manage this, the synthetic images were classified by the ViT-L/16 model, which had the highest ROC-AUC score. This model generated a new subset from the 50,000 synthetic images by choosing only those it classified with high confidence (probability > 0.6 for melanoma and < 0.4 for nevus), as seen in

Figure 3. This method added only high-quality synthetic images that were close to real images to the training set.

Figure 4 presents a sample of the synthetic images from the GANs. The left column has synthetic nevus images, and the right column has synthetic melanoma images. These images have a range of colors, textures, and patterns found in real dermoscopic images. The GANs produced realistic images that could be useful for training the classification model.

Before the addition of synthetic images, the ISIC-19 dataset had 12,875 nevus and 4,522 melanoma images (class proportions of 74.0% nevus and 26.0% melanoma). After filtering with the ViT-L/16 model, 27,793 nevus and 18,438 melanoma synthetic images were chosen. This created a new training dataset with a total of 40,668 nevus and 22,960 melanoma images (adjusting the class proportions to 63.9% nevus and 36.1% melanoma), which increased the size and diversity of the training data.

3.3. Model Performance with Data Augmentation

Including high-confidence synthetic images in the training data produced measurable performance gains for all model architectures.

Table 3 presents results from five independent training runs on both the validation (ISIC-2019) and external test (MN187) sets. The uniformity of these improvements across multiple runs supports the conclusion that the data augmentation strategy provided general benefit.

The ViT-L/16 architecture remained the strongest performer, reaching a top ROC-AUC of 0.915 on the challenging MN187 test set, as presented in

Figure 5. This result exceeds its previous best score of 0.902. Other models also showed substantial improvement; the ConvNeXt-XL model advanced from a previous score of 0.885 to 0.894. Similar positive trends were observed for the ViT-B/16, ResNet-152, EfficientNet-B7, and DenseNet-201 models, confirming that the augmented dataset created a more effective training environment.

To evaluate the statistical significance of these improvements, the best run from each model was compared against the established benchmark, Mole Analyzer Pro, using DeLong’s test. The results of this analysis are in

Table 4. The standard ViT-L/16 model, with an AUC of 0.915, achieved a statistically significant advantage over the commercial software (p = 0.032).

A refined version of the ViT-L/16 model was developed for further improvement. This fine-tuned model, included in

Figure 5 and

Table 4, was created by initializing with the best ViT-L/16 run, freezing its classification head, and unfreezing the final six transformer layers. These layers were then trained for an additional 30 epochs with a reduced learning rate. This process allowed the higher-level feature representations to adapt more specifically to skin lesion data characteristics. The outcome was a model that achieved a ROC-AUC of 0.926 on the MN187 test set. The statistical comparison with Mole Analyzer Pro for this model produced a p-value of 0.006, providing evidence that its improved performance is statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence for the potential of Vision Transformers in melanoma classification using dermatoscopic images. The ViT-L/16 model achieved the highest ROC-AUC score among all evaluated models, reflecting its capacity to capture global contextual information in dermatoscopic images. This performance supports the advantages of self-attention mechanisms when analyzing complex visual patterns found in skin lesions.

Despite promising findings, the ROC-AUC improvements compared with Mole Analyzer Pro were not statistically significant in the initial experiments. This outcome reflects the difficulty of achieving meaningful performance gains in medical imaging, where high baselines and small datasets constrain model development. Adding synthetic images produced by a GAN helped address data scarcity and produced a statistically significant increase in ROC-AUC for the ViT-L/16 model. This result implies that data augmentation can improve model generalization in domains with limited annotated data.

Using a GAN to generate synthetic images provided a practical approach to expand the training dataset. Filtering synthetic images based on model confidence reduced the chance of introducing artifacts or biases. This selection process limited the set to higher-quality synthetic images, which likely improved ViT-L/16 performance. However, reliance on synthetic data also raises concerns about possible limitations, including the risk of overfitting to the synthetic distribution.

When comparing ViT and CNN architectures, ViT generally outperformed the CNN-based models in this study. Although model size is an important factor, the superior performance of ViT-L/16 cannot be explained by parameter count alone. For example, the CNN-based ConvNeXt Large model contains more parameters than ViT-L/16 yet achieved lower performance. The results support the view that the Transformer architecture itself, with its self-attention mechanism, may be better suited for the task. The finding is consistent with recent reports showing stronger outcomes from ViT on a range of medical imaging applications [

28,

31,

32]. However, ViT models require greater computational resources during both training and inference, which can limit their practicality in resource-constrained settings.

Another important point to consider is the need for statistical validation to evaluate model performance. Although ViT-L/16 produced higher ROC-AUC scores than Mole Analyzer Pro, the initial lack of statistical significance points to the need for methods such as the DeLong test to confirm that observed improvements are unlikely to be due to chance. In a clinical context, reporting performance metrics without such validation could be misleading, as a seemingly better model might not represent a true advancement. For medical applications, where decisions impact patient care, establishing statistical significance is a fundamental step in building trust in a model’s reported capabilities. This practice helps to ensure that performance claims are reliable and not simply the result of variability in the test dataset.

The fine-tuned ViT-L/16 variant, obtained by unfreezing only the top six transformer blocks and training them with a reduced learning rate, delivered an incremental yet meaningful improvement (ROC-AUC 0.926; p = 0.006 vs. Mole Analyzer Pro) over the frozen-backbone configuration (best ROC-AUC 0.915). This suggests that limited, targeted adaptation of high-level self-attention layers helps align global contextual features with dermoscopic lesion morphology without incurring instability or overfitting. The constrained unfreezing strategy likely preserved generic representations in earlier layers while refining class-discriminative cues, such as pigment network irregularity, streak distribution, and peripheral asymmetry. Expanding fine-tuning depth, applying layer-wise learning rate decay, or integrating lightweight adapters (e.g. LoRA) may further improve performance, but these strategies also carry an increased risk of overfitting in limited-data and domain-shift settings [

57,

58,

59].

Commercial skin analysis platforms such as Mole Analyzer Pro, which currently rely on convolutional neural networks, could benefit substantially from the integration of Vision Transformer models. These newer models generalize more effectively, providing accurate diagnoses on data not seen during training. They also adapt more readily to specific tasks and can incorporate filtered synthetic data with success. An important architectural advantage is their flexibility with input sizes, which removes the need for preprocessing steps such as padding and resizing. This combination of properties reduces manual image tuning and leads to more consistent performance in practice.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an evaluation of the clinical potential of Vision Transformers for melanoma classification was performed in two datasets. Using a standardized experimental framework, the ViT-L/16 architecture was found to consistently outperform conventional CNN based models and the commercial FotoFinder’s MoleAnalyzer Pro system. A statistically significant increase in diagnostic accuracy was observed with the incorporation of confidence filtered GAN generated images, supporting the value of synthetic data in addressing the challenges of class imbalance and limited annotated clinical datasets.

The findings offer several conclusions. First, ViTs provide clear advantages in modeling the global contextual features of dermoscopic images, allowing for a more accurate differentiation between malignant and benign lesions. Second, GAN based augmentation, when carefully filtered, improves both data diversity and generalization, mitigating the limitations imposed by relatively small medical imaging datasets. Third, statistical validation, including the use of DeLong’s test, is considered essential to confirm that observed performance gains are both reproducible and clinically meaningful.

This study establishes that transformer-based architectures, when combined with structured data augmentation, represent a promising direction for next-generation clinical decision support systems in dermatology. The methodology presented, which integrates transformer fine-tuning, selective synthetic data generation, and statistical significance testing, offers a reproducible framework for future research and clinical application.

Future work should focus on multi-center validation to strengthen generalizability, the integration of clinical metadata and patient risk factors to provide diagnostic context, and the use of explainable AI methods to build clinician trust and adoption. Moving in these directions could help transition Vision Transformers from research into real-world clinical practice, contributing to earlier melanoma detection and better patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and J.Z.; methodology, A.G.; software, A.G. and J.Z.; formal analysis, X.H.; investigation, A.G.; resources, G.P.-C. and T.B.; data curation, J.Z., G.P.-C. and T.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, X.H.; supervision, X.H., G.P.-C. and T.B.; project administration, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida (IRB #007837) and the James A. Haley Veterans Hospital—VA IRBNet Number: 1816729.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. All dermoscopic images were collected from a de-identified database, and it would not have been feasible to obtain informed consent from all patients, as some may have moved away or passed away. The IRB approved this waiver as described in the protocol: “We are requesting a waiver of consent to use the de-identified dermoscopy images of patients seen at the VA dermatology clinic, that are normally stored on the VA Sharepoint drive. This study cannot be conducted without biopsy proven dermoscopy pictures, and the recruitment timeline would be impracticably long to do this prospectively as patients come in. It would be impracticable to obtain consent from the patients whose images we intend to use because they are de-identified, so we would not be able to contact the patients, and some of them may have passed away or left the VA system.”

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study (including the MN187 clinical dermoscopic images and derived model outputs) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to patient privacy and institutional review constraints, the raw clinical images cannot be placed in a public repository. De-identified metadata, trained model weights, and synthetic GAN-generated images can be shared subject to a data use agreement.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided to A. Garcia for his Ph.D. studies at Worcester Polytechnic Institute by the Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (SENACYT) and the Government of the Republic of Panama through the Fulbright-SENACYT fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Signal pathways of melanoma and targeted therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platz, A.; Egyhazi, S.; Ringborg, U.; Hansson, J. Human cutaneous melanoma; a review of NRAS and BRAF mutation frequencies in relation to histogenetic subclass and body site. Molecular Oncology 2008, 1, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.E.; Edmiston, S.N.; Alexander, A.; Groben, P.A.; Parrish, E.; Kricker, A.; Armstrong, B.K.; Anton-Culver, H.; Gruber, S.B.; From, L.; et al. Association Between NRAS and BRAF Mutational Status and Melanoma-Specific Survival Among Patients With Higher-Risk Primary Melanoma. JAMA Oncology 2015, 1, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.H. Molecular Frontiers in Melanoma: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Advances. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, G.; Capone, M.; Ascierto, M.L.; Gentilcore, G.; Stroncek, D.F.; Casula, M.; Sini, M.C.; Palla, M.; Mozzillo, N.; Ascierto, P.A. Main roads to melanoma. Journal of Translational Medicine 2009, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.; Earnshaw, C.H.; Virós, A. Ultraviolet light and melanoma. The Journal of Pathology 2018, 244, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; De Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatology 2022, 158, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pinto, G.; Mignozzi, S.; La Vecchia, C.; Levi, F.; Negri, E.; Santucci, C. Global trends in cutaneous malignant melanoma incidence and mortality. Melanoma Research 2024, 34, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Guy, G.P. Stemming the Rising Incidence of Melanoma: Calling Prevention to Action. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2016, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, D.E. Precursors to melanoma and their mimics: nevi of special sites. Modern Pathology 2006, 19, S4–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raluca Jitian (Mihulecea), C.; Frățilă, S.; Rotaru, M. Clinical-dermoscopic similarities between atypical nevi and early stage melanoma. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2021, 22, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Su, J.; Zheng, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Peng, C.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, W. A Clinicopathological Analysis of Melanocytic Nevi: A Retrospective Series. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 681668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekler, A.; Utikal, J.S.; Enk, A.H.; Solass, W.; Schmitt, M.; Klode, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Sondermann, W.; Franklin, C.; Bestvater, F.; et al. Deep learning outperformed 11 pathologists in the classification of histopathological melanoma images. European Journal of Cancer 2019, 118, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, T.J.; Hekler, A.; Enk, A.H.; Klode, J.; Hauschild, A.; Berking, C.; Schilling, B.; Haferkamp, S.; Schadendorf, D.; Fröhling, S.; et al. A convolutional neural network trained with dermoscopic images performed on par with 145 dermatologists in a clinical melanoma image classification task. European Journal of Cancer 2019, 111, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, T.J.; Hekler, A.; Enk, A.H.; Klode, J.; Hauschild, A.; Berking, C.; Schilling, B.; Haferkamp, S.; Schadendorf, D.; Holland-Letz, T.; et al. Deep learning outperformed 136 of 157 dermatologists in a head-to-head dermoscopic melanoma image classification task. European Journal of Cancer 2019, 113, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jojoa Acosta, M.F.; Caballero Tovar, L.Y.; Garcia-Zapirain, M.B.; Percybrooks, W.S. Melanoma diagnosis using deep learning techniques on dermatoscopic images. BMC Medical Imaging 2021, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenssle, H.; Fink, C.; Schneiderbauer, R.; Toberer, F.; Buhl, T.; Blum, A.; Kalloo, A.; Hassen, A.B.H.; Thomas, L.; Enk, A.; et al. Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Annals of Oncology 2018, 29, 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr-Esfahani, E.; Samavi, S.; Karimi, N.; Soroushmehr, S.; Jafari, M.; Ward, K.; Najarian, K. Melanoma detection by analysis of clinical images using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA; 2016; pp. 1373–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigar, N.; Umar, M.; Shahzad, M.K.; Islam, S.; Abalo, D. A Deep Learning Approach Based on Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Skin Lesion Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 113715–113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, C.; Celebi, M.E.; Marques, J.S. Explainable skin lesion diagnosis using taxonomies. Pattern Recognition 2021, 110, 107413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorfuzzaman, M. An explainable stacked ensemble of deep learning models for improved melanoma skin cancer detection. Multimedia Systems 2021, 28, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridha, K.; Uddin, M.M.; Shin, J.; Khadka, S.; Mridha, M.F. An Interpretable Skin Cancer Classification Using Optimized Convolutional Neural Network for a Smart Healthcare System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41003–41018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Miah, M.S.; Haque, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.K. An enhanced technique of skin cancer classification using deep convolutional neural network with transfer learning models. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 5, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.A.; Hosny, K.M.; Fouad, M.M. Skin Lesions Classification Into Eight Classes for ISIC 2019 Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Transfer Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 114822–114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Al-Amidie, M.; Al-Asadi, A.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Shamma, O.; Fadhel, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Santamaría, J.; Duan, Y. Novel Transfer Learning Approach for Medical Imaging with Limited Labeled Data. Cancers 2021, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K.M.; Kassem, M.A.; Foaud, M.M. Classification of skin lesions using transfer learning and augmentation with Alex-net. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0217293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International conference on learning representations (ICLR); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Luo, S.; Greer, P. A Novel Vision Transformer Model for Skin Cancer Classification. Neural Processing Letters 2023, 55, 9335–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladhadh, S.; Alsanea, M.; Aloraini, M.; Khan, T.; Habib, S.; Islam, M. An Effective Skin Cancer Classification Mechanism via Medical Vision Transformer. Sensors 2022, 22, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Sommella, P.; Carratù, M.; O’Nils, M.; Lundgren, J. A Deep CNN Transformer Hybrid Model for Skin Lesion Classification of Dermoscopic Images Using Focal Loss. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Miao, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Yang, F.; et al. An improved transformer network for skin cancer classification. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 149, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshed, M.A.; Mumtaz, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Ahmed, S.; Tahir, M.; Shafi, M. Multi-Class Skin Cancer Classification Using Vision Transformer Networks and Convolutional Neural Network-Based Pre-Trained Models. Information 2023, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.C.F.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 International symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018); 2018; pp. 168–8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.J.; Tariq, A.; Adejumo, T.; Trivedi, H.; Gichoya, J.W.; Banerjee, I. Systematic Review of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Medical Image Classification and Segmentation. Journal of Digital Imaging 2022, 35, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goceri, E. GAN based augmentation using a hybrid loss function for dermoscopy images. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behara, K.; Bhero, E.; Agee, J.T. Skin Lesion Synthesis and Classification Using an Improved DCGAN Classifier. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanparast, T.; Shamsipour, M.; Ayatollahi, A.; Delavar, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Samadi, A.; Firooz, A. Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracy of Teledermoscopy, Face-to-Face Examinations and Artificial Intelligence in the Diagnosis of Melanoma. Indian Journal of Dermatology 2024, 69, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerminara, S.E.; Cheng, P.; Kostner, L.; Huber, S.; Kunz, M.; Maul, J.T.; Böhm, J.S.; Dettwiler, C.F.; Geser, A.; Jakopović, C.; et al. Diagnostic performance of augmented intelligence with 2D and 3D total body photography and convolutional neural networks in a high-risk population for melanoma under real-world conditions: A new era of skin cancer screening? European Journal of Cancer 2023, 190, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.E.; Kamali, K.; Dorey, R.A.; MacIntyre, O.C.; Cleminson, K.; MacGillivary, M.L.; Green, P.J.; Langley, R.G.; Purdy, K.S.; DeCoste, R.C.; et al. Using Artificial Intelligence as a Melanoma Screening Tool in Self-Referred Patients. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 2024, 28, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R.I.; Trepanowski, N.; Chang, M.S.; Tepedino, K.; Gianacas, C.; McNiff, J.M.; Fung, M.; Braghiroli, N.F.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Multicenter prospective blinded melanoma detection study with a handheld elastic scattering spectroscopy device. JAAD International 2024, 15, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLellan, A.N.; Price, E.L.; Publicover-Brouwer, P.; Matheson, K.; Ly, T.Y.; Pasternak, S.; Walsh, N.M.; Gallant, C.J.; Oakley, A.; Hull, P.R.; et al. The use of noninvasive imaging techniques in the diagnosis of melanoma: a prospective diagnostic accuracy study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2021, 85, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.; Rosic, N.; Stapelberg, M.; Hudson, J.; Coxon, P.; Furness, J.; Walsh, J.; Climstein, M. Performance of Commercial Dermatoscopic Systems That Incorporate Artificial Intelligence for the Identification of Melanoma in General Practice: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.L.; Tada, M.; So, A.; Torres, R. Artificial intelligence and skin cancer. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11, 1331895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.K.; Blum, A.; Kommoss, K.; Enk, A.; Toberer, F.; Rosenberger, A.; Haenssle, H.A. Assessment of Diagnostic Performance of Dermatologists Cooperating With a Convolutional Neural Network in a Prospective Clinical Study: Human With Machine. JAMA Dermatology 2023, 159, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIC 2019 challenge, 2019.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., Vol. 30. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Emara, T.; Afify, H.M.; Ismail, F.H.; Hassanien, A.E. A Modified Inception-v4 for Imbalanced Skin Cancer Classification Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES); 2019; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamel, M.; Iliopoulos, C.; Lim, Z. Deep learning approaches and data augmentation for melanoma detection. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 37, 10591–10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, K.; Akbar, S.; Shoukat, A. A Majority Voting based Ensemble Approach of Deep Learning Classifiers for Automated Melanoma Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC); 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Training generative adversarial networks with limited data. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2020; pp. 12104–12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVlabs. StyleGAN2-ADA PyTorch, 2020.

- Obuchowski, N.A.; Bullen, J.A. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves: review of methods with applications in diagnostic medicine. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2018, 63, 07TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Medical Diagnostic Test Evaluation. Caspian Journal of Internal Medicine 2013, 4, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Song, M.; Tan, X.; Wang, W. Four overlooked errors in ROC analysis: how to prevent and avoid. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2025, 30, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, L.; Alok, A.; Jose, J.; Iosifidis, A. Structured pruning adapters. Pattern Recognition 2024, 156, 110724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, G.S. Efficient learning rate adaptation based on hierarchical optimization approach. Neural Networks 2022, 150, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razuvayevskaya, O.; Wu, B.; Leite, J.A.; Heppell, F.; Srba, I.; Scarton, C.; Bontcheva, K.; Song, X. Comparison between parameter-efficient techniques and full fine-tuning: A case study on multilingual news article classification. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0301738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).