1. Introduction

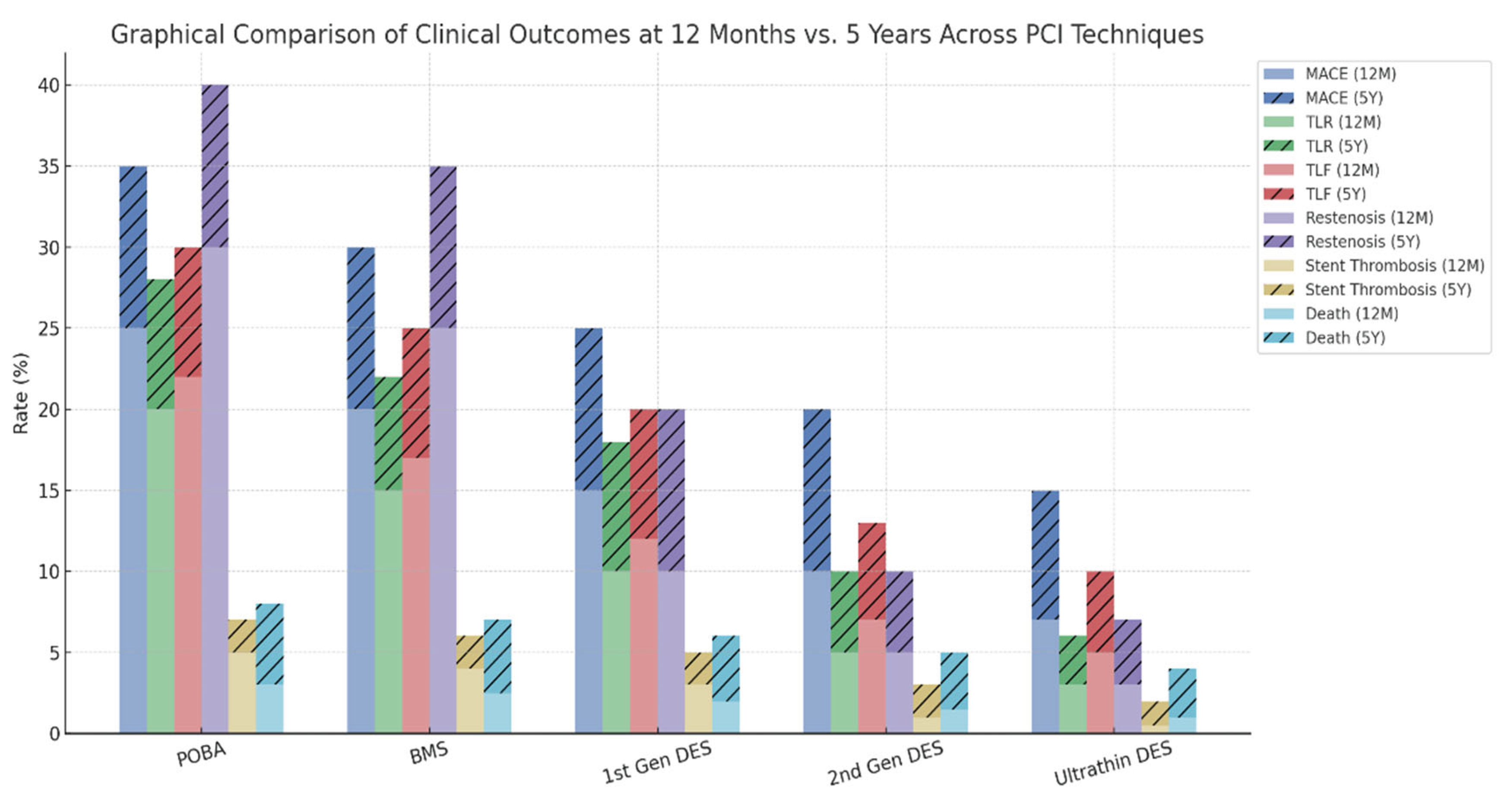

The management of coronary artery disease (CAD) has evolved dramatically since Andreas Grüntzig introduced balloon angioplasty in 1977 [

1]. While revolutionary, early balloon angioplasty was limited by elastic recoil, abrupt vessel closure, and restenosis rates as high as 30-50% [

2]. These challenges prompted the development of bare-metal stents (BMS) in the late 1980s, which provided mechanical scaffolding to maintain vessel patency [

3]. However, BMS introduced neointimal hyperplasia, leading to in-stent restenosis (ISR) in 20-30% of cases [

4]. The advent of drug-eluting stents (DES) in the early 2000s, which released antiproliferative agents to inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation, reduced restenosis rates to below 10% [

5]. Despite their efficacy, DES are associated with delayed endothelialization, late stent thrombosis, and the need for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), increasing bleeding risks [

6].

While the introduction of bare-metal stents (BMS) and first-generation DES dramatically reduced restenosis and target lesion revascularization (TLR) compared to POBA, long-term outcomes such as MACE and stent thrombosis remained suboptimal. Subsequent evolution toward second-generation and ultrathin DES further improved safety and efficacy, yet certain limitations persist, particularly in small vessels, bifurcations, and high-bleeding-risk populations.

Despite advancements in DES technology, the presence of a permanent metallic scaffold remains a central limitation, associated with delayed vascular healing, persistent inflammation, and late thrombotic events. These observations have revived interest in non-scaffold-based therapies, particularly drug-coated balloons (DCBs), which deliver antiproliferative agents locally without leaving behind foreign material.

DCBs have demonstrated promising results, especially in in-stent restenosis (ISR), small vessel disease, and specific high-risk anatomical settings. The absence of permanent implants with DCBs allows for preservation of native vasomotion and may reduce long-term complications such as very late stent thrombosis or neoatherosclerosis. In this context, the integration of DCBs into the PCI armamentarium represents a paradigm shift —moving from permanent scaffolding toward transient drug delivery with long-lasting vascular benefit.

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) emerged as an innovative solution to address these limitations, embodying a leave nothing behind philosophy. By delivering antiproliferative drugs directly to the vessel wall during brief balloon inflation, DCBs avoid permanent implants, reducing risks of chronic inflammation, neoatherosclerosis, and stent-related complications [

7]. DCBs also enable shorter DAPT durations, a critical advantage for patients at high bleeding risk (HBR) [

8].

Initially developed for ISR, DCBs have expanded to small vessel disease (SVD), de novo lesions, and complex anatomies, supported by robust clinical evidence [20, 22]. This review provides an in-depth analysis of the pharmacological foundations, clinical applications, and future directions of DCBs in PCI, emphasizing their role in modern cardiology.

Thus, while DES remains the cornerstone in most PCI scenarios, DCBs offer a complementary strategy, especially where long-term outcomes require minimization of metal burden and improved vessel healing. Future trials will further define their optimal role.

2. Advantages of Drug-Coated Balloons Compared to Stents

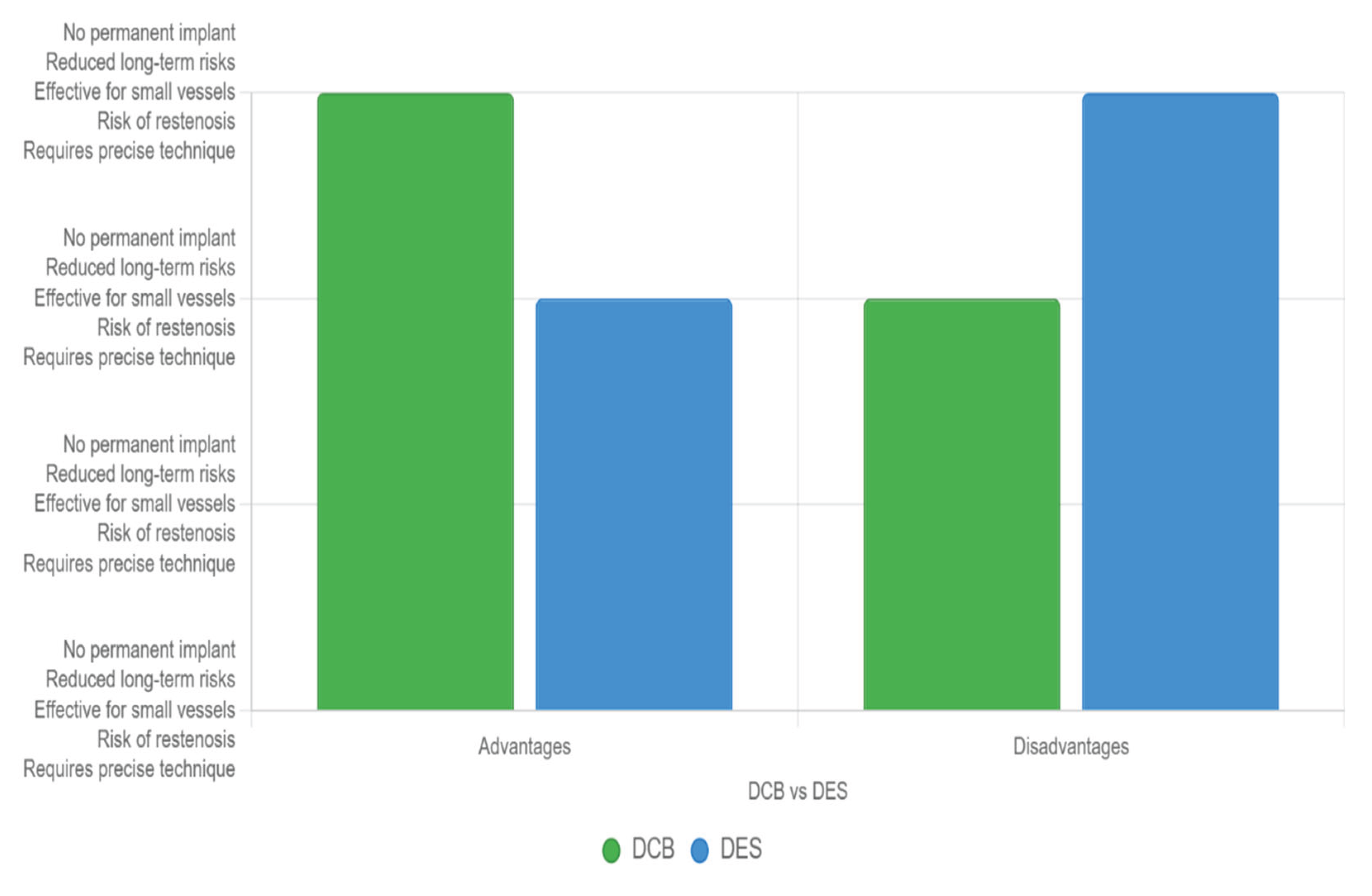

DES, introduced earlier, provide a permanent metallic scaffold that prevents acute vessel closure and significantly reduces restenosis by delivering antiproliferative drugs over time. Their primary advantages include long-term vessel patency and effectiveness in complex or long lesions, making them a cornerstone for many procedures. However, DES carry disadvantages such as the risk of late stent thrombosis, necessitating extended dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), and potential for in-stent restenosis or neoatherosclerosis, adding procedural and follow-up complexity.

In contrast, drug-coated balloons (DCBs), a more recent innovation, offer a distinct therapeutic benefit by delivering antiproliferative agents directly to the vessel wall without leaving a permanent implant, (“Nothing left behind” concept), thereby addressing several limitations associated with drug-eluting stents (DES). Their key advantages include reduced long-term risks like thrombosis, no need for prolonged DAPT, and suitability for small vessels, bifurcation lesions, or in-stent restenosis cases where scaffolds are less ideal. This makes DCBs a flexible option, particularly in patients with contraindications to long-term anticoagulation.

One of the primary advantages of DCBs lies in their ability to maintain vascular physiology. By avoiding the implantation of a metallic scaffold, DCBs allow natural arterial healing while preserving vessel elasticity and function. In contrast, DES permanently alter the vessel environment and may impair vasomotion.

A key clinical benefit of DCBs is the reduced risk of late and very late stent thrombosis. First-generation DES were linked to higher rates of these complications due to delayed endothelialization and chronic inflammation induced by metallic struts.

Since DCBs do not leave a foreign body behind, the risk of such adverse events is minimized, offering a safer long-term profile in appropriately selected patients.

DCBs also enable a shorter duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), which is especially valuable in patients at high bleeding risk. The absence of a permanent implant reduces the need for extended DAPT, thereby minimizing bleeding complications without compromising efficacy in restenosis prevention.

Moreover, DCBs are particularly advantageous in anatomically challenging scenarios such as small vessel disease and bifurcation lesions. Stenting in small arteries is often associated with higher restenosis rates, and bifurcations may require complex strategies to protect side branches. DCBs deliver uniform drug distribution without mechanical limitations, making them an attractive option in these contexts.

As a stent-free modality with comparable efficacy, DCBs represent a significant advancement in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Emerging data, including results from the BASKET-SMALL 2 and PICCOLETO II trials, support the role of DCBs in de novo lesions, demonstrating similar long-term outcomes and lower revascularization rates compared to DES.

However, DCBs have drawbacks, including the need for precise deployment to ensure adequate drug transfer and a potential for higher restenosis rates due to the absence of a scaffold, which can limit their efficacy in certain anatomies or unstable lesions (see

Figure 3).

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) offer significant advantages over drug-eluting stents (DES) in patients with hypersensitivity to metals, a concern in percutaneous coronary intervention due to potential adverse reactions to stent materials like nickel or cobalt. DCBs deliver antiproliferative drugs to the vessel wall without leaving a permanent metallic scaffold, mitigating risks associated with metal hypersensitivity, such as chronic inflammation, in-stent restenosis (ISR), and late stent thrombosis.

Metal hypersensitivity can trigger local inflammatory responses, contributing to neoatherosclerosis and ISR. DES, despite advancements, retain a metallic structure that may provoke such reactions, particularly in sensitive patients. A comprehensive review notes that DCBs avoid “allergy to metal or polymer,” reducing chronic inflammation and preserving vessel anatomy. The absence of a permanent implant eliminates the risk of long-term foreign body reactions, which can exacerbate hypersensitivity-related complications.

Clinical trials support DCBs’ efficacy in settings where metal avoidance is critical. The PACCOCATH ISR-I and -II trials demonstrated that paclitaxel-coated DCBs significantly reduced late lumen loss (LLL) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared to plain balloon angioplasty in BMS-ISR, with no metal-related complications [

9]. Similarly, the PEPCAD II trial showed DCBs outperforming paclitaxel-eluting stents in LLL reduction, suggesting effective drug delivery without a metallic scaffold. For de novo lesions, the DEBUT trial found DCBs noninferior to bare-metal stents (BMS) in high-bleeding-risk patients, with no hypersensitivity-related adverse events reported, highlighting their safety in avoiding metal implants.

In conclusion, DCBs provide a compelling alternative to stents by eliminating metal-related hypersensitivity risks, reducing inflammation, and enabling shorter DAPT. Ongoing trials like TRANSFORM II will further clarify their role, but current evidence strongly supports DCBs for patients with metal hypersensitivity undergoing PCI.

The complementary nature of DES and DCBs allows cardiologists to tailor interventions based on patient-specific factors—lesion length, vessel size, calcification, and comorbidities. DES excel in providing structural support and durability, while DCBs offer a less invasive, scaffold-free approach with quicker recovery profiles. This duality ensures both devices have a place in modern practice, with the choice driven by clinical evidence, procedural goals, and individual patient outcomes, optimizing safety and efficacy in coronary artery disease management.

Figure 3.

Main advantages and disadvantages between stents and DCBs.

Figure 3.

Main advantages and disadvantages between stents and DCBs.

3. Pharmacological Premises

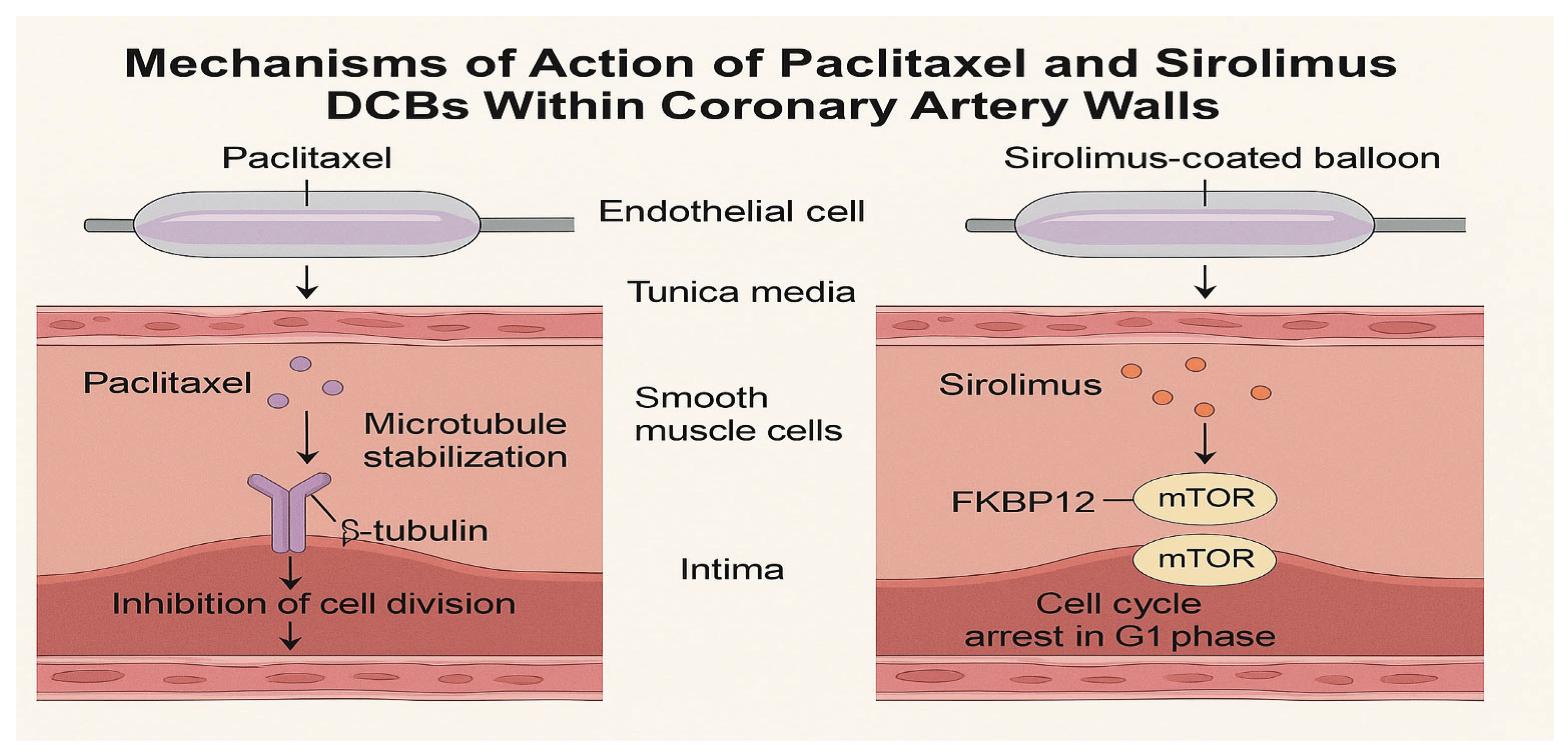

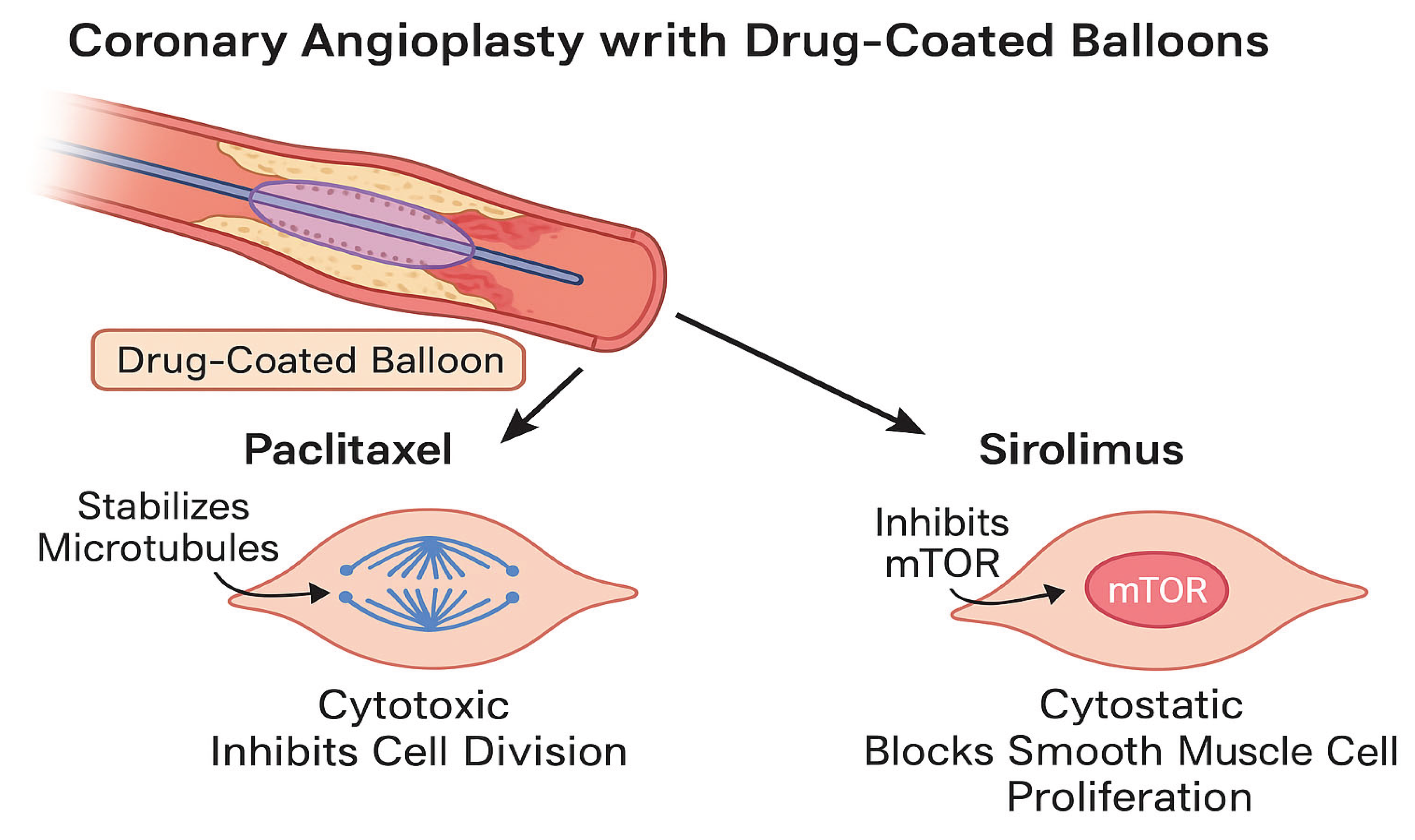

DCBs deliver antiproliferative agents to the arterial wall during 30-60 seconds of balloon inflation, inhibiting neointimal hyperplasia without permanent scaffolds [

7]. The two primary drugs used are paclitaxel and sirolimus, each with distinct pharmacological profiles.

Paclitaxel, a cytotoxic diterpenoid, binds to the subunit of tubulin, stabilizing microtubules and arresting cell division in the G2/M phase [

11]. Its high lipophilicity (logP 3.96) enables rapid tissue uptake and prolonged retention, with tissue concentrations detectable for weeks after a single application [

13]. This property makes paclitaxel ideal for DCBs, as it ensures sustained antiproliferative effects despite brief exposure. However, its cytotoxic nature can delay endothelial healing, potentially increasing inflammation in some cases [

11,

13].

Sirolimus, a cytostatic macrolide, inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway by binding to FKBP12, arresting the cell cycle in the G1 phase [

12]. With lower lipophilicity (logP 2.5) and a shorter tissue half-life, sirolimus requires advanced delivery systems to achieve sustained effects [

14]. Recent innovations, including phospholipid carriers and micro-reservoir formulations, enhance sirolimus transfer and retention, improving its efficacy in DCBs [

15]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that sirolimus promotes faster endothelialization and reduces inflammatory responses compared to paclitaxel, suggesting a superior healing profile [

12].

- 2.

Drug Delivery Technologies and Excipient Systems

The efficacy of DCBs hinges on the excipient matrix, which facilitates drug transfer from the balloon surface to the arterial wall. Paclitaxel-coated balloons commonly use excipients such as shellac, urea, iopromide, or contrast agents to enhance solubility and adhesion [

7]. These form a thin film that enables rapid drug release upon inflation, achieving high local concentrations (up to 500 μg/g tissue) within seconds [

13].

Sirolimus-coated balloons require more complex excipients due to their lower lipophilicity and larger molecular size (MW 914 Da vs 853 Da for paclitaxel).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of action of paclitaxel and sirolimus drug-coated balloons (DCBs) within coronary artery walls. Paclitaxel stabilizes microtubules, leading to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, while sirolimus inhibits the mTOR pathway, arresting the cell cycle in the G1 phase. Both drugs are delivered rapidly to the vessel wall during balloon inflation, with paclitaxel exhibiting prolonged retention due to its high lipophilicity, and sirolimus relying on advanced excipient systems for sustained effects.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of action of paclitaxel and sirolimus drug-coated balloons (DCBs) within coronary artery walls. Paclitaxel stabilizes microtubules, leading to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, while sirolimus inhibits the mTOR pathway, arresting the cell cycle in the G1 phase. Both drugs are delivered rapidly to the vessel wall during balloon inflation, with paclitaxel exhibiting prolonged retention due to its high lipophilicity, and sirolimus relying on advanced excipient systems for sustained effects.

Formulations such as butyryl-tri-n-hexyl-citrate(BTHC), polylactic-co-glycolic acid -PLGA), and bioresorbable phospholipids sustain drug release and improve vascular uptake [

15]. For example, the Selution SLR drug-coating-balloon uses a micro-reservoir system to maintain sirolimus release for up to 60 days [

14].

Table 1 summarizes key drug and excipient properties.

Figure 2.

Distinct cellular mechanisms of paclitaxel and sirolimus during coronary angioplasty with DCBs. Paclitaxel targets microtubules to prevent smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, while sirolimus inhibits the mTOR pathway, achieving a similar antiproliferative effect with a more favorable endothelial healing profile.

Figure 2.

Distinct cellular mechanisms of paclitaxel and sirolimus during coronary angioplasty with DCBs. Paclitaxel targets microtubules to prevent smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, while sirolimus inhibits the mTOR pathway, achieving a similar antiproliferative effect with a more favorable endothelial healing profile.

Although Drug-Coated Balloons (DCBs) emerged later than stents, including drug-eluting stents (DES), both have established unique roles in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), reflecting evolving cardiovascular care.

4. Clinical Applications and Indications of DCBs

DCBs are indicated for a range of coronary lesions where stents are suboptimal or contraindicated, including ISR, SVD, de novo lesions, bifurcation lesions, and HBR patients. Their versatility stems from their ability to deliver drugs without permanent implants, preserving vessel physiology and reducing long-term complications [

10].

ISR, caused by neointimal proliferation following stent deployment, remains a primary indication for DCBs. Re-treating ISR with additional stents increases metal burden, procedural complexity, and restenosis risk [

15]. Landmark trials, including PEPCAD II [

16], ISAR-DESIRE 3 [

8], and RIBS IV [

17], have established DCBs as non-inferior or superior to repeat DES for both BMS- and DES-ISR. The DAEDALUS meta-analysis (n=2,110) confirmed comparable target lesion failure (TLF) rates (12.2% vs. 13.5%) and lower bleeding complications with DCBs due to shorter DAPT durations [

19].

The AGENT IDE trial (2024), a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT), further validated the efficacy of the Agent paclitaxel-coated DCB (2 μg/mm

2) versus conventional balloon angioplasty in 600 patients with ISR. The primary endpoint, TLF at 1 year, was significantly lower with DCB (17.9% vs. 28.7%; HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.420.84, p=0.003). Secondary out- comes included reduced TLR (13.0% vs. 24.7%, p=0.001), target vessel myocardial infarction (5.8% vs. 11.1%, p=0.02), and stent thrombosis (0% vs. 3.2%, p<0.001), with no difference in mortality [

28].

- b.

Small Vessel Disease (SVD)

SVD (vessel diameter <2.75 mm) is associated with higher restenosis and thrombosis risks due to limited luminal area [

19]. The BASKET-SMALL 2 trial (n=758) demonstrated non-inferiority of paclitaxel DCBs to second-generation DES, with similar MACE rates at 12 months (7.5% vs. 7.3%) and 36 months (12.8% vs. 12.4%) [

19]. The RESTORE SVD trial (n=230) corroborated these findings, reporting comparable late lumen loss (LLL) (0.38 mm vs. 0.35 mm) and lower rates of target lesion thrombosis with DCBs [

21]. Imaging studies suggest better endothelial recovery and reduced late inflammation in DCB-treated vessels [

21].

- c.

De Novo Lesions

DCBs are increasingly utilized for de novo lesions, particularly in HBR or elderly patients where prolonged DAPT is undesirable. The PICCOLETO II trial (n=232) compared sirolimus DCBs to paclitaxel DCBs, reporting lower LLL (0.22 mm vs. 0.37 mm, p=0.03) and similar MACE rates [

21]. The FIRE trial (n=1,200) in frail elderly patients demonstrated non-inferiority of a DCB-based strategy to DES for major cardiac endpoints (9.2% vs. 9.8%, p=0.67), with shorter DAPT durations [

23]. The BIO-RISE CHINA and FUTURE SVD trials further support sirolimus DCBs for de novo lesions, showing reduced TLR and improved vessel healing [26, 27].

- d.

Bifurcation Lesions

Bifurcation lesions pose technical challenges due to complex anatomy and risk of side branch occlusion. DCBs are effective for side branch treatment after main branch stenting, preserving vessel anatomy and reducing the need for complex two-stent strategies [

24]. Observational data and small RCTs report favorable patency rates (9095%) and lower MACE with DCB use in side branches [

25].

- e.

High Bleeding Risk (HBR) Patients

HBR patients, including the elderly, those with chronic kidney disease, or recent bleeding, benefit from DCBs shorter DAPT requirements (1-3 months vs. 6-12 months for DES) [

10]. The ESC 2023 guidelines endorse DCBs for HBR patients, citing reduced bleeding events and comparable efficacy to DES in ISR and SVD [

10].

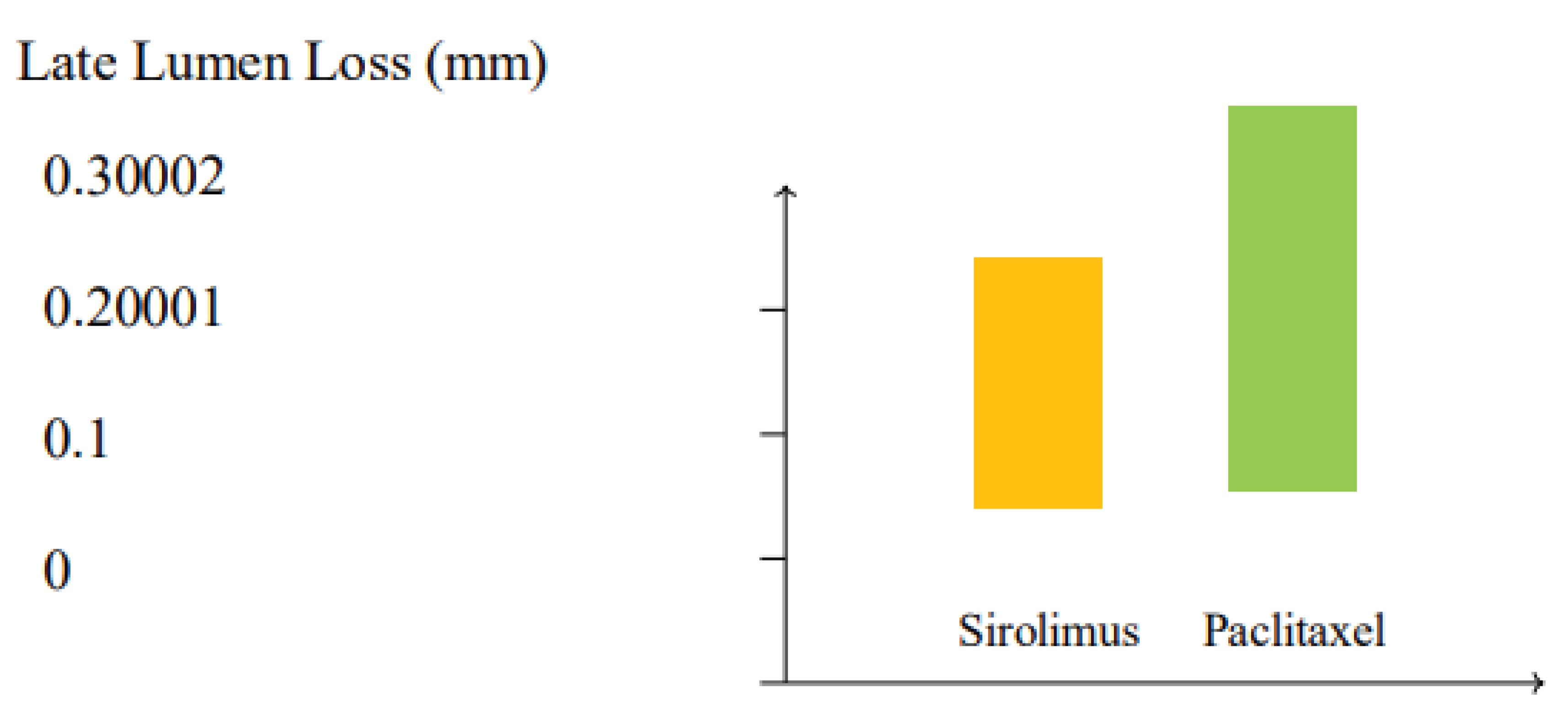

5. Comparative Efficacy: Paclitaxel vs. Sirolimus

Head-to-head comparisons of paclitaxel and sirolimus DCBs are limited but growing. A 2023 meta-analysis (n=3,245) found comparable TLF (11.8% vs. 12.1%) and TLR (7.9% vs. 8.2%) rates between paclitaxel and sirolimus DCBs in ISR and SVD [

34]. Sirolimus DCBs showed a trend toward lower LLL (0.24 mm vs. 0.31 mm, p=0.06) and improved endothelial healing, as evidenced by optical coherence tomography (OCT) studies [

34]. The TRANSFORM II trial (ongoing) aims to further compare sirolimus DCBs to everolimus-eluting stents in de novo lesions [

35].

Figure 4.

Comparison of late lumen loss (LLL) between paclitaxel and sirolimus drug-coated balloons (DCBs) based on meta-analysis data. Sirolimus DCBs demonstrate a trend toward lower LLL (0.24 mm) compared to paclitaxel DCBs (0.31 mm), suggesting improved vessel patency (p=0.06).

Figure 4.

Comparison of late lumen loss (LLL) between paclitaxel and sirolimus drug-coated balloons (DCBs) based on meta-analysis data. Sirolimus DCBs demonstrate a trend toward lower LLL (0.24 mm) compared to paclitaxel DCBs (0.31 mm), suggesting improved vessel patency (p=0.06).

- b.

Sirolimus Paclitaxel Safety and Healing

Paclitaxel DCBs association with increased morbidity in peripheral artery disease raised concerns, but coronary DCB studies have not substantiated these risks [

29]. Sirolimus DCBs demonstrate superior endothelialization and reduced inflammatory infiltrates in preclinical models and OCT studies, potentially lowering long-term complications [

33]. The PEPPER registry (n=816) reported low MACE rates (6.5%) with sirolimus DCBs in ISR, supporting their safety [

33].

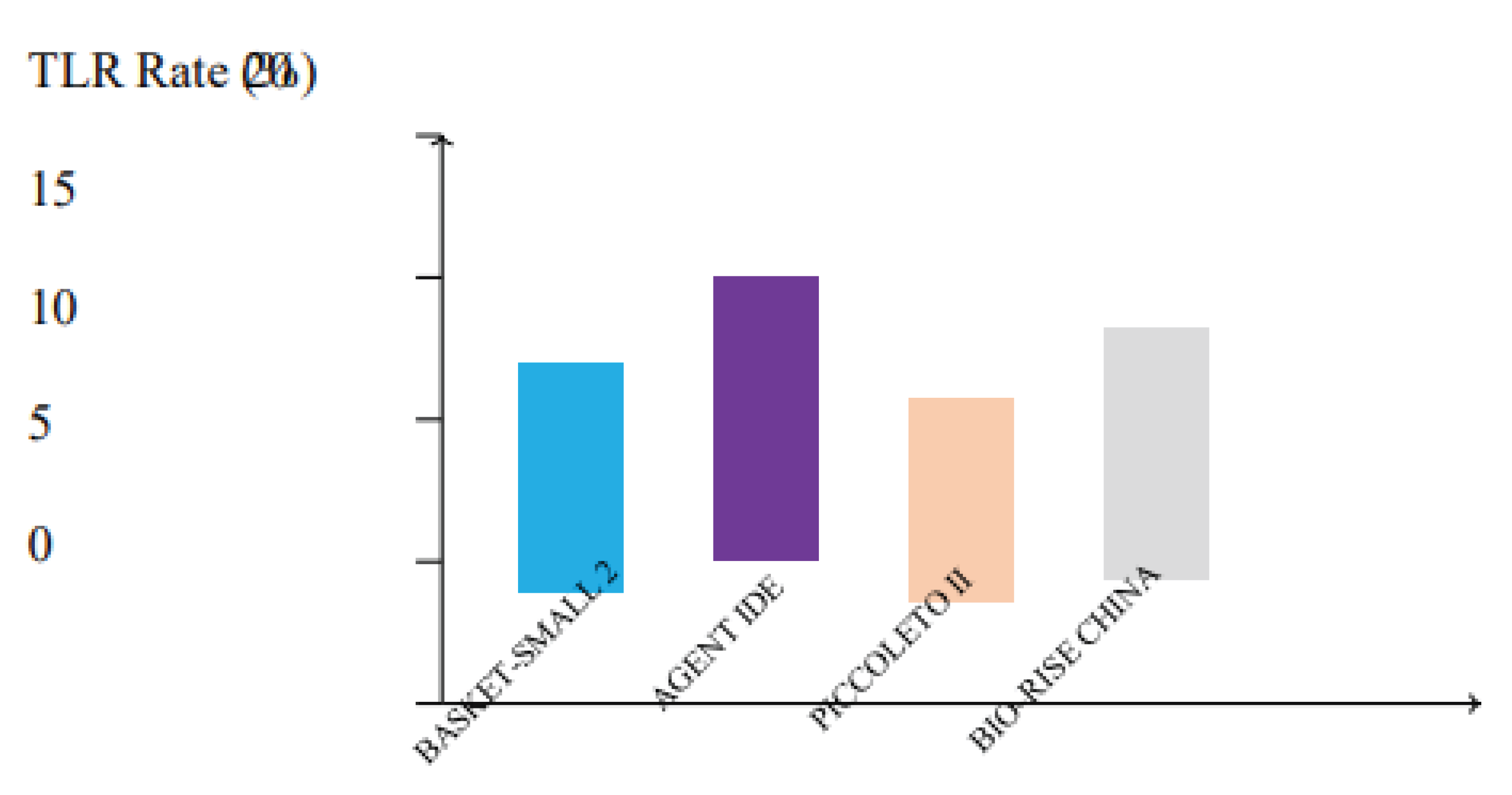

Figure 5.

Target lesion revascularization (TLR) rates across major clinical trials comparing drug-coated balloons (DCBs). Trials such as BASKET-SMALL 2, AGENT IDE, PICCOLETO II, and BIO-RISE CHINA demonstrate low TLR rates, with sirolimus and paclitaxel DCBs showing comparable efficacy in reducing the need for repeat interventions.

Figure 5.

Target lesion revascularization (TLR) rates across major clinical trials comparing drug-coated balloons (DCBs). Trials such as BASKET-SMALL 2, AGENT IDE, PICCOLETO II, and BIO-RISE CHINA demonstrate low TLR rates, with sirolimus and paclitaxel DCBs showing comparable efficacy in reducing the need for repeat interventions.

6. Technical Considerations

Optimal DCB outcomes require meticulous lesion preparation and procedural adherence:

Lesion Predilatation: Use semi-compliant or scoring balloons to achieve <30% residual stenosis [

30].

Avoidance of Dissections: Flow-limiting dissections (type C or greater) increase failure risk [

31].

Angiographic Goals: Achieve TIMI 3 flow and avoid geographic mismatch [

30].

Intravascular Imaging: IVUS and OCT enhance lesion characterization and balloon sizing, reducing failure rates [

31].

Suboptimal lesion preparation is the leading cause of DCB failure, emphasizing the need for imaging-guided PCI [

32].

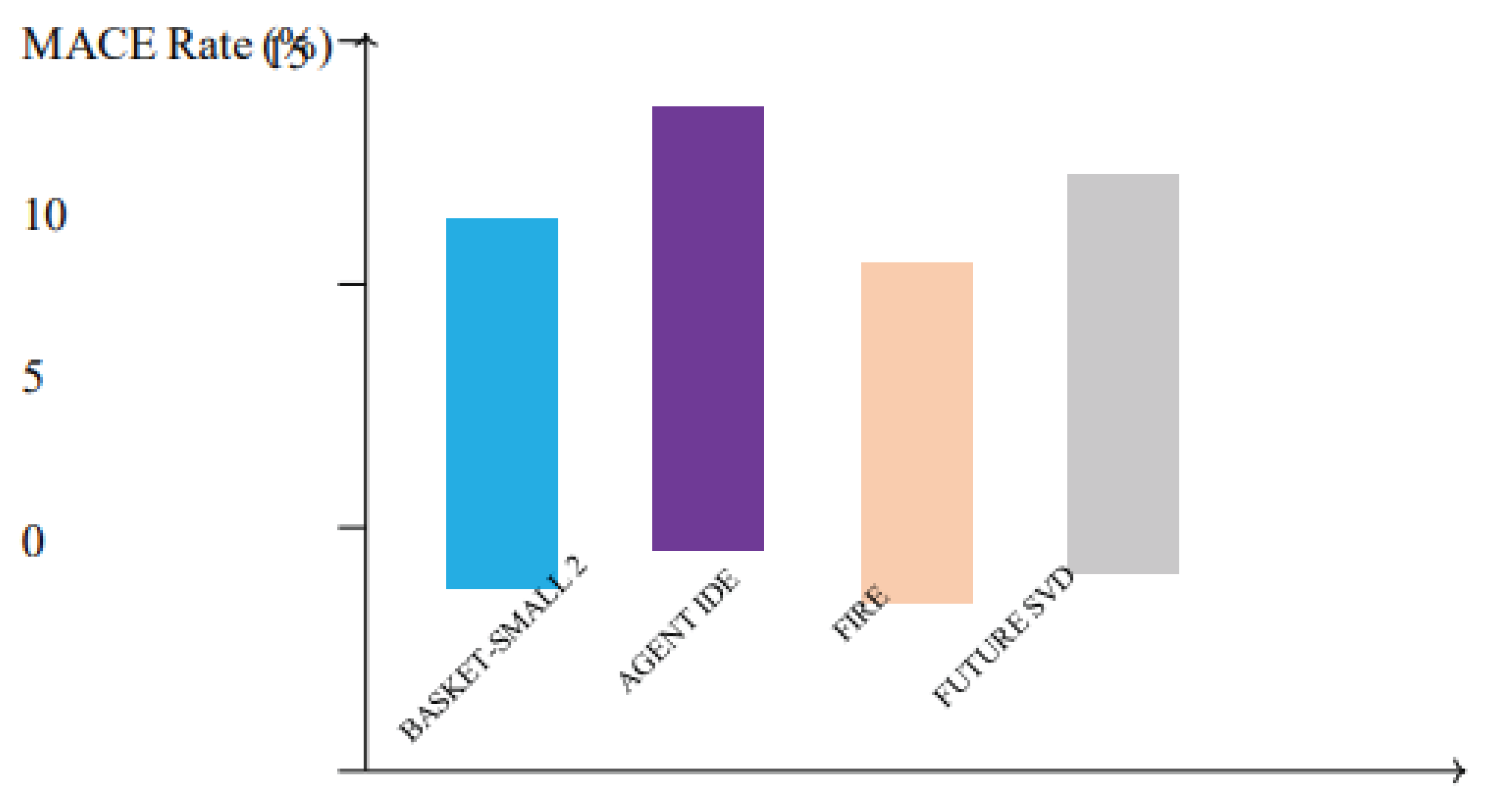

Figure 6.

Incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in key clinical trials evaluating drug-coated balloons (DCBs). Studies including BASKET-SMALL 2, AGENT IDE, FIRE, and FUTURE SVD report low MACE rates, highlighting the safety and efficacy of DCBs in diverse coronary lesions.

Figure 6.

Incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in key clinical trials evaluating drug-coated balloons (DCBs). Studies including BASKET-SMALL 2, AGENT IDE, FIRE, and FUTURE SVD report low MACE rates, highlighting the safety and efficacy of DCBs in diverse coronary lesions.

7. Discussion

DCBs represent a paradigm shift in PCI, offering a stentless alternative that addresses the limitations of DES while maintaining comparable efficacy. Their ability to deliver antiproliferative drugs without permanent implants reduces risks of stent thrombosis, neoatherosclerosis, and chronic inflammation, which are particularly relevant in complex lesions and HBR patients [7, 10]. The shorter DAPT requirement is a critical advantage, as prolonged DAPT increases bleeding risks, particularly in elderly or comorbid patients [

8]. Trials like AGENT IDE and BASKET-SMALL 2 underscore DCBs efficacy in ISR and SVD, with outcomes rivaling or surpassing DES [28, 20].

The transition from paclitaxel to sirolimus DCBs marks a significant advancement. Sirolimuss cytostatic mechanism and improved healing profile address concerns about paclitaxels cytotoxicity, potentially broadening DCB indications [

14]. However, sirolimus DCBs require sophisticated excipient systems, which increase production complexity and cost [

14]. Ongoing trials, such as TRANSFORM II, will clarify their role in de novo lesions and complex anatomies [

35].

Challenges remain, including optimizing drug formulations for calcified lesions and ensur- ing uniform drug delivery in tortuous vessels [

30]. The role of AI in lesion characterization and procedural planning is an exciting frontier, with potential to enhance precision and outcomes [

32]. Additionally, the economic impact of DCBs, particularly in resource-limited settings, warrants further study, as their upfront costs may be offset by reduced long-term complications and DAPT duration [

33].

8. Future Perspectives

The future of DCBs is promising, with several avenues for innovation:

Dual-Drug DCBs: Combining paclitaxel and sirolimus could leverage synergistic ef- fects, potentially reducing restenosis rates further [

15].

Ultra-Thin Balloons: These enhance deliverability in complex anatomies, minimizing vessel trauma [

14].

Novel Coatings: Biodegradable matrices and nanoparticle-based systems may improve drug elution and reduce inflammation [

15].

AI Integration: AI-driven algorithms for lesion characterization, balloon sizing, and patient selection could optimize outcomes [

32].

Expanded Indications: Trials like TRANSFORM II and SELUTION ISR are exploring DCBs in acute coronary syndromes and chronic total occlusions [

35].

Advancements in imaging, such as high-resolution OCT and AI-enhanced IVUS, will further refine procedural precision, ensuring optimal lesion preparation and DCB deployment [

31]. As evidence accumulates, DCBs may become the preferred strategy for a broader range of coronary lesions, particularly in HBR and complex anatomy patients.

9. Conclusions

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) represent a major innovation in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), providing an effective, stent-free therapeutic alternative for selected coronary lesions. Their capacity to deliver antiproliferative agents locally, without the long-term presence of a metallic scaffold, has redefined treatment strategies for in-stent restenosis (ISR), small vessel disease (SVD), de novo lesions, and bifurcation segments [

10]. By eliminating permanent implants, DCBs reduce the incidence of late and very late stent-related complications, such as thrombosis and neoatherosclerosis, while allowing for shorter durations of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)—a critical advantage in high-bleeding-risk (HBR) patients.

Recent evidence suggests that sirolimus-based DCBs may provide superior vascular healing and broader applicability compared to paclitaxel-based counterparts. Clinical trials such as PICCOLETO II and BIO-RISE CHINA have demonstrated the feasibility and safety of sirolimus DCBs, with promising efficacy in complex coronary lesions and small vessels [22, 26]. However, optimal results with DCBs are highly dependent on meticulous lesion preparation, appropriate vessel sizing, and the use of intracoronary imaging modalities such as IVUS or OCT to guide therapy [

20].

As the field of interventional cardiology continues to evolve, the role of DCBs is likely to expand. Advances in drug-release technologies, balloon material engineering, and integration of artificial intelligence for real-time decision-making are expected to further enhance the safety, efficacy, and precision of DCB-based PCI. In this context, DCBs are not merely an alternative to drug-eluting stents—they are emerging as a foundational strategy in the management of coronary artery disease, especially in anatomically or clinically challenging scenarios.

Ultimately, the continued adoption of DCBs will rely on robust clinical evidence, practitioner familiarity with technique-specific protocols, and thoughtful patient selection. When applied appropriately, DCBs offer a tailored, minimally invasive, and durable solution that aligns with the evolving goals of modern coronary revascularization.

References

- Grüntzig AR, Senning A, Siegenthaler WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary artery stenosis: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1978;301(2):6168. [CrossRef]

- Serruys PW, Luijten HE, Beatt KJ, et al. Incidence of restenosis after successful coronary angioplasty: a time-related phenomenon. Circulation. 1988;77(2):361371. [CrossRef]

- Sigwart U, Puel J, Mirkovitch V, et al. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(12):701706. [CrossRef]

- Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, et al. A randomized comparison of coronary stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(8):496501. [CrossRef]

- Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus- eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(23):17731780. [CrossRef]

- McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E, et al. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 2004;364(9444):15191521. [CrossRef]

- Scheller B, Speck U, Abramjuk C, et al. Paclitaxel balloon coating, a novel method for prevention and therapy of restenosis. Circulation. 2004;110(7):810814. [CrossRef]

- Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and bare-metal stents for the treatment of ISR: the ISAR-DESIRE 3 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(23):23142323.

- Scheller B, Hehrlein C, et al. Treatment of Coronary In-Stent Restenosis with a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Catheter N Engl J Med 2006;355:2113-2124. [CrossRef]

- Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2023 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:10261194.

- Axel DI, Kunert W, Göggelmann C, et al. Paclitaxel inhibits arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in vitro and in vivo using local drug delivery. Circulation. 1997;96:636645. [CrossRef]

- Marx SO, Marks AR. Bench to bedside: the development of rapamycin and its application to stent restenosis. Circ Res. 2001;89:650662.

- Kleber FX, Schulz A, Waliszewski M, et al. Local paclitaxel induces late lumen enlargement in coronary arteries after balloon angioplasty. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99(7):543549.

- Ielasi A, Tespili M, Giannini F, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloons for the treatment of coronary lesions: a review of available evidence. Int J Cardiol. 2022;343:18.

- Buccheri D, Frigerio M, Rognoni A, et al. New-generation drug-coated balloons: from bench to bedside. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2019;33(3):335346.

- Siontis GC, Stefanini GG, Mavridis D, et al. Percutaneous coronary interven- tions for the treatment of in-stent restenosis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):655664. [CrossRef]

- Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel- coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: the three-year results of the PEPCAD II ISR study. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(8):926934. [CrossRef]

- Alfonso F, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, Cárdenas A, et al. A randomized comparison of drug- eluting balloon vs everolimus-eluting stent in patients with ISR: the RIBS IV trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(1):2333.

- Giacoppo D, Alfonso F, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty vs. drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: a comprehensive, collaborative, individual patient data meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials (DAEDALUS study). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(38):37153728. [CrossRef]

- Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label RCT. Lancet. 2018;392(10150):849856. [CrossRef]

- Tang KH, Ong TK, Sivapatham T, et al. One-year outcomes of the RESTORE SVD China study: drug-coated balloon for small coronary vessel disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(4):S32S33.

- Cortese B, Di Palma G, Guimaraes MG, et al. Drug-coated balloon versus drug- eluting stent in coronary lesions: the PICCOLETO II trial. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;13(20):25042513.

- Baan J Jr, Claessen BE, van der Schaaf RJ, et al. A randomized trial of a DCB strategy versus a DES strategy in frail elderly patients with coronary artery disease: the FIRE trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):17801789.

- Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G, et al. Drug-coated balloons for side branch treatment in bifurcation lesions. EuroIntervention. 2020;15(16):14261434.

- Jimenez-Quevedo P, Sabaté M, et al. Bifurcation lesion management using DCB: insights from real-world registry data. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97(5):853861.

- Xu B, Gao R, Yang Y, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus-coated bal- loon vs paclitaxel DCB for ISR: BIO-RISE CHINA. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(19):24082417.

- Her AY, Kim YH, Shin ES, et al. Sirolimus- versus paclitaxel-eluting balloons in de novo coronary lesions: FUTURE SVD trial. Circulation. 2021;144(2):108118.

- Yeh RW, Shlofmitz R, Moses J, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon vs uncoated balloon for coronary in-stent restenosis: the AGENT IDE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(12):10151024. [CrossRef]

- Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, et al. Risk of death following appli- cation of paclitaxel-coated balloons in PAD: meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e011245. [CrossRef]

- Waksman R, Pakala R. Drug-eluting balloon: the comeback kid? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(4):352358. [CrossRef]

- Lee JM, Shin ES, Nam CW, et al. Physiological and anatomical predictors of DCB failure: the CLI-DIS study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2019;12(10):964976.

- Medrano-Gracia P, Sato Y, Otsuka K, et al. AI-enhanced PCI strategy planning using intravascular imaging. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2021;14(2):221231.

- Wöhrle J, Zadura M, Minda K, et al. Safety and performance of sirolimus-coated balloon for coronary ISR: PEPPER registry. Int J Cardiol. 2020;305:5055.

- Li Y, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. Sirolimus- versus paclitaxel-coated balloons for coronary interventions: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiol. 2023;44(5):789799.

- Greco A, Sciahbasi A, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary artery disease: rationale and design of the TRANSFORM II randomized clinical trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100(4):544552. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).