1. Introduction

Alamandine (ALA) was identified and characterized in 2013 by a research team led by Dr. Robson Santos during an investigation into the function of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) [

1]. This discovery, alongside the identification of Angiotensin-(1-7) [Ang-(1-7)] in 1988 [

2], marks a significant milestone in the interpretation of the RAS.

These findings reinforced the concept of two axes within the RAS that have seemingly opposing functions, which balance each other in maintaining health. The classical axis, represented by ACE-AngII-AT1, coexists with a novel axis involving ACE2-Ang-(1-7)/ALA-Mas/MrgD, which plays a central role in the pathophysiology of various diseases. However, despite these advancements, clear gaps persist in our understanding of this system.

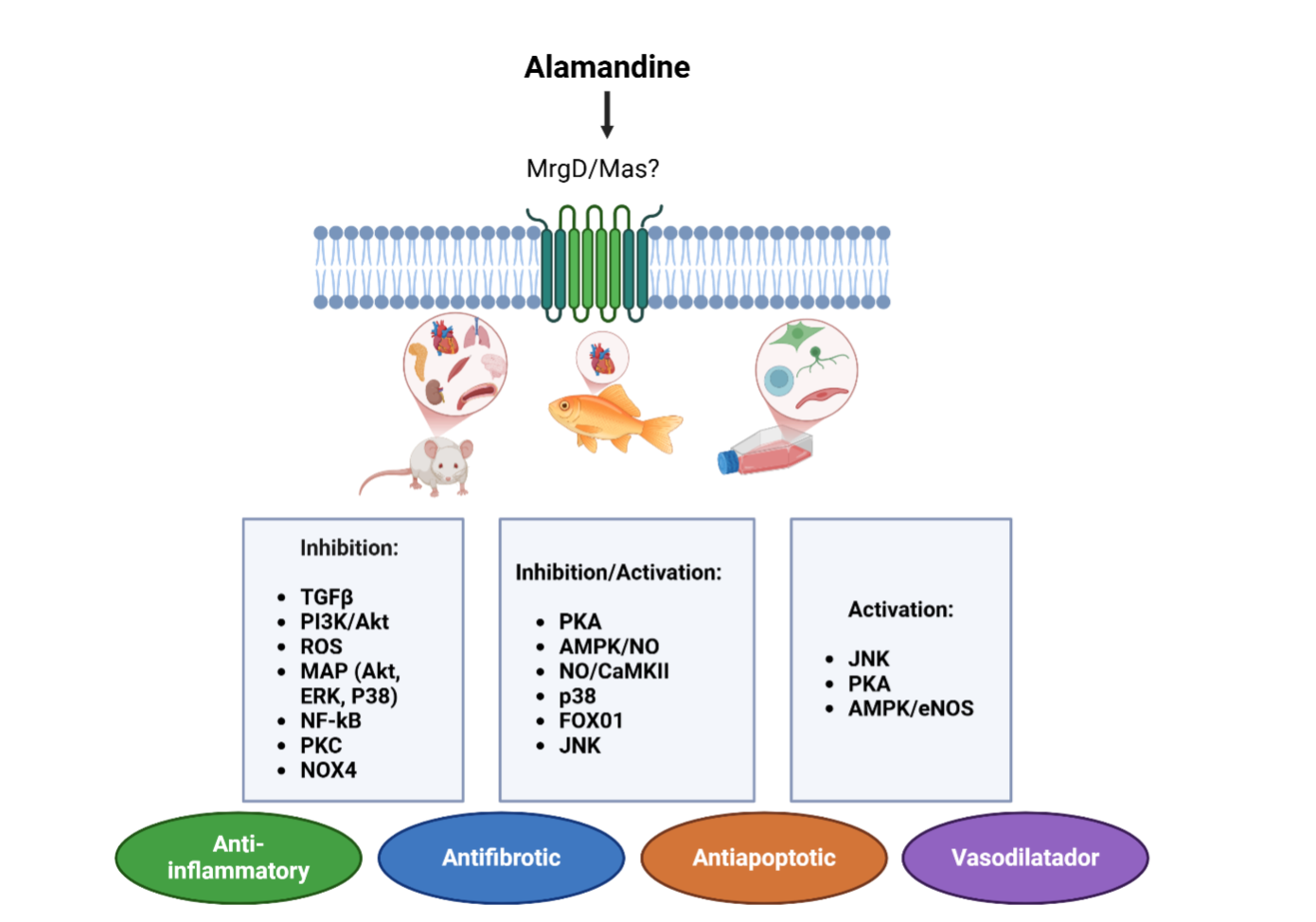

The primary mechanism by which ALA functions is through the activation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling, specifically involving the Mas receptor (MrgD). This activation leads to various downstream effects, including vasodilation, anti-inflammatory actions[

3], and antifibrotic effects [

4], which closely resemble those of Ang-(1-7) [

5].

Literature data demonstrate that ALA induces vasodilation both in vitro and in vivo, likely through the activation of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) to produce nitric oxide (NO) [

6]. Furthermore, ALA exhibits antifibrotic effects, likely through the inhibition of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling, thus reducing collagen deposition in the heart [

7] and kidneys [

8]. These results revealed the importance of the new axis in counteracting the harmful effects of excessive angiotensin II (Ang II) action.

Building on this understanding, we propose a scoping review using an emerging methodology to synthesize existing knowledge on the topic. Although not all articles present the highest quality, considering the limited literature available, all studies discussing ALA's mechanisms of action were included. This method also identifies gaps, opportunities, and research priorities to guide future studies on its mechanisms of action in the body.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review employs the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology [

9] and is registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF, DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/CG9U4). The review follows five stages: identifying research questions, finding relevant studies, selecting eligible studies, collecting and recording data, and summarizing and reporting results. Detailed descriptions of each stage are provided below [

9].

2.1. Stage 1: Identification of the Research Question

The main research question was formulated using the 'Population,' 'Concept,' and 'Context' (PCC) framework, covering both in vivo and in vitro studies. This approach focuses on identifying the primary signaling pathways that explain the ALA's mechanism of action. In this context, we considered all body systems, including the kidneys, brain, cardiovascular system, heart, eyes, lungs, and others.

Based on the PCC framework, our main research question was: What mechanisms of action of ALA are described in the literature? This led to the following sub-questions:

2.2. Stage 2: Identification of Relevant Studies (Search Strategy)

All studies that evaluated the mechanism of action of ALA, regardless of the body system studied, were eligible for this scoping review. We did not impose restrictions on publication date or language. However, qualitative studies, reviews, editorials, comments, abstracts, and conference proceedings were excluded.

Initially, a search was conducted in the PubMed database to identify potential keywords for the search strategy, based on the titles, abstracts, and keywords of retrieved articles. Subsequently, a final search was performed across the PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science databases (see

Supplementary Table S1 for all search strategies). All databases were searched on April 14, 2023, and updated on January 30, 2025.

2.3. Stage 3: Selection of Studies for the Review

Endnote® was employed as reference management software to facilitate data management. Duplicate studies were removed using the software's automated deduplication function. Subsequently, Rayyan® software was utilized, and two independent reviewers (ATS and JF) assessed the eligibility of each report through a two-step process. Initially, they reviewed the titles and abstracts to select all potentially eligible articles. Later, ATS and JF read the full texts to confirm eligibility. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through consensus, and if necessary, a third reviewer (IAM) was consulted.

2.4. Stage 4: Data Extraction

The same two reviewers (ATS and JF) independently extracted data from all eligible studies using a data extraction spreadsheet created in Microsoft Office Excel®. A pilot test of this spreadsheet was conducted using five randomly selected full texts before proceeding with data extraction, ensuring consistent data extraction by the reviewers and avoiding ambiguities and errors.

Supplementary Table S2 summarizes the extracted data.

2.5. Stage 5: Summary of Data and Synthesis of Results

We used descriptive statistics to outline the characteristics of studies on ALA mechanisms of action, incorporating tables and graphs to present the collected data. This scoping review is presented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) checklist (

Supplementary Table S3) [

10].

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies and General Characteristics of Selected Studies

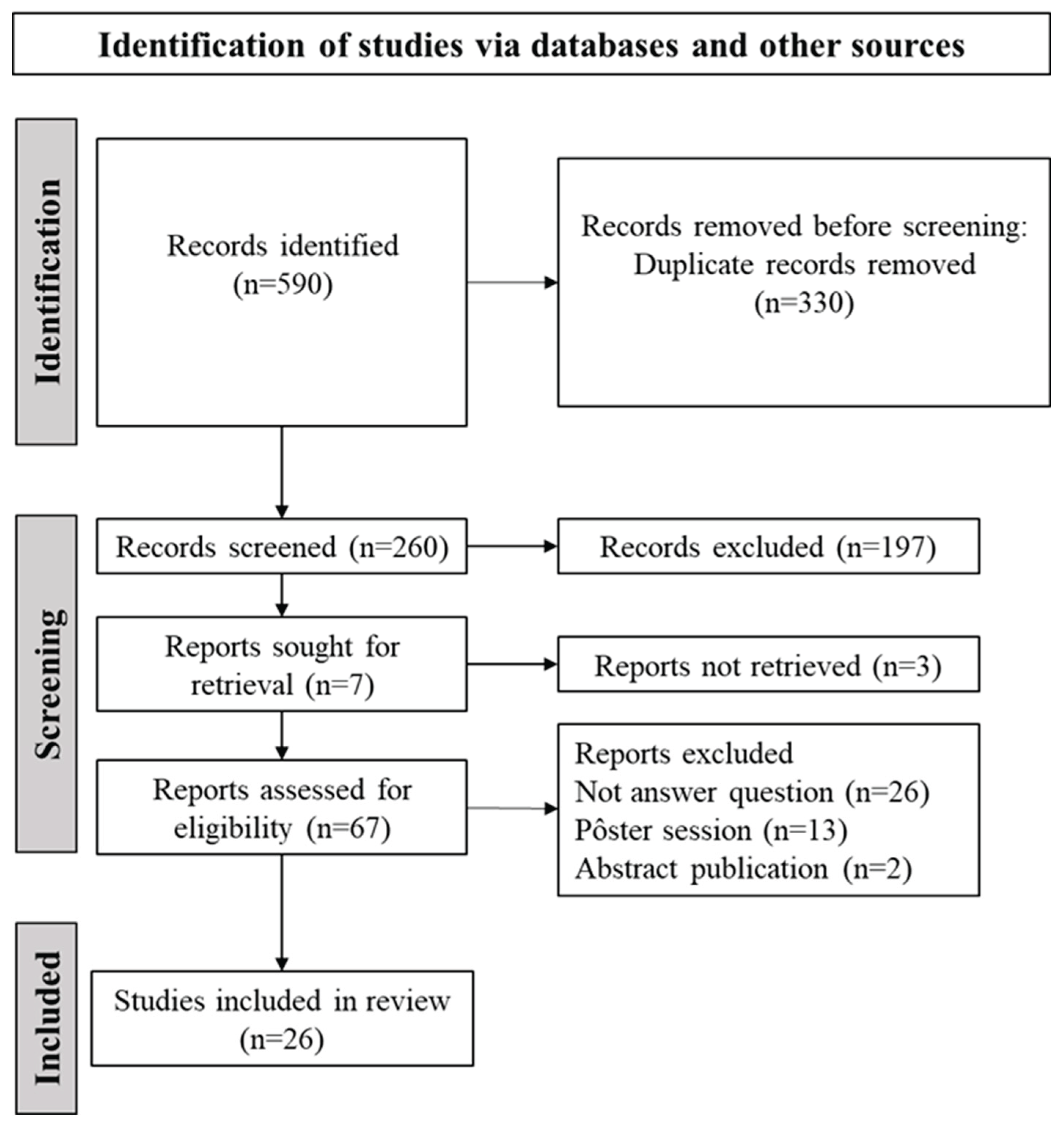

Figure 1 presents the study selection flowchart. A total of 590 records were identified across all databases. After automated deduplication and screening of titles and abstracts, 67 records remained for full-text examination and data extraction. Of these, 41 studies were excluded for the following reasons: 26 did not address the research question, 13 were posters, and 2 were abstracts. Consequently, 26 studies were deemed eligible [

4,

6,

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

Supplementary Table S4 provides a list of excluded studies along with justifications. Detailed characteristics of each study are presented in

Supplementary Table S5. Most studies were published in 2022 (n=6) [

7,

11,

13,

14,

15,

16].

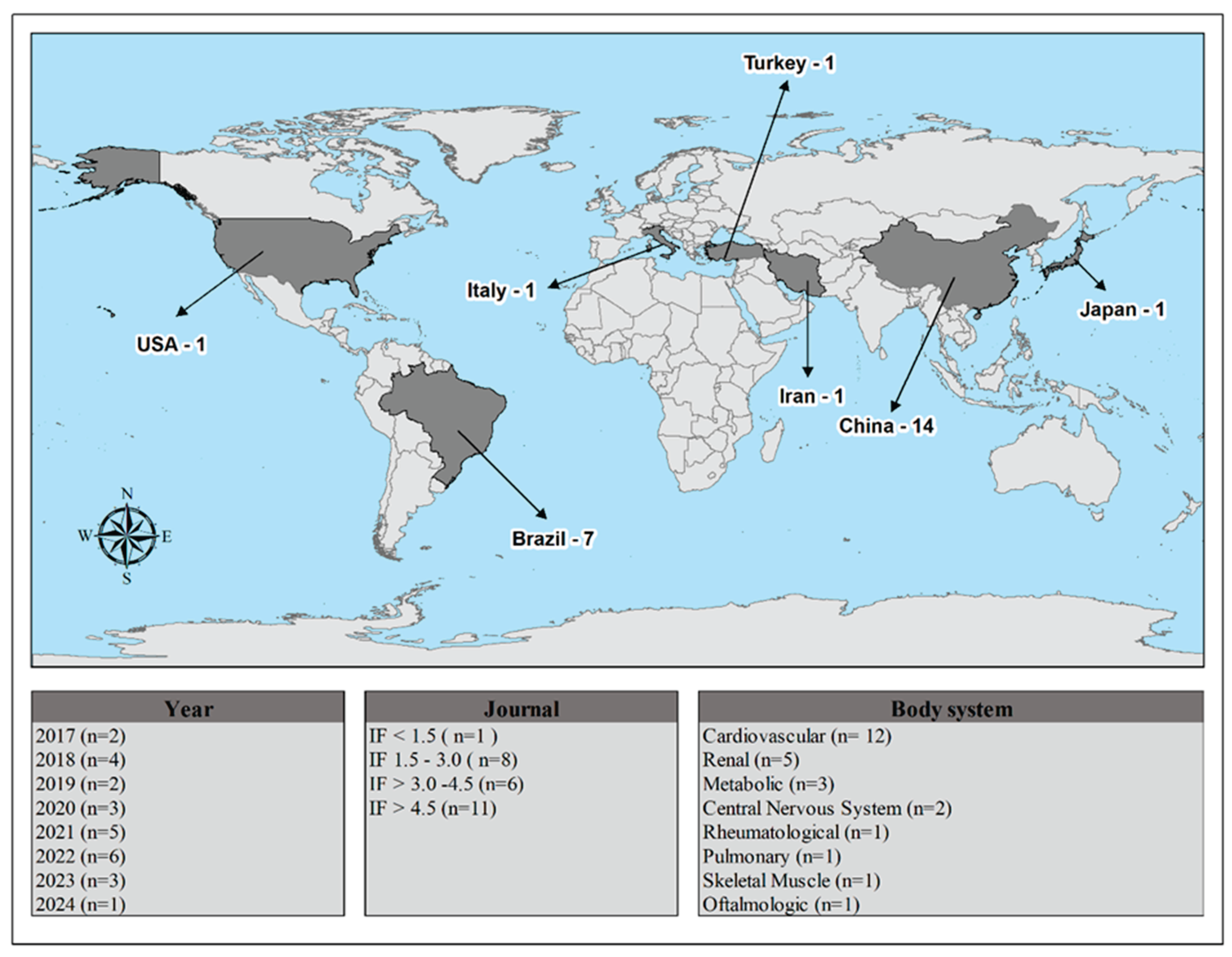

Figure 2 provides a summary of the study features, including publication year, country, impact factor, and body system. All studies were described in English and were experimental in nature (100%). The studies were published in journals with an impact factor above 4.5 (n=11), and the cardiovascular system was the most studied body system (n=12).

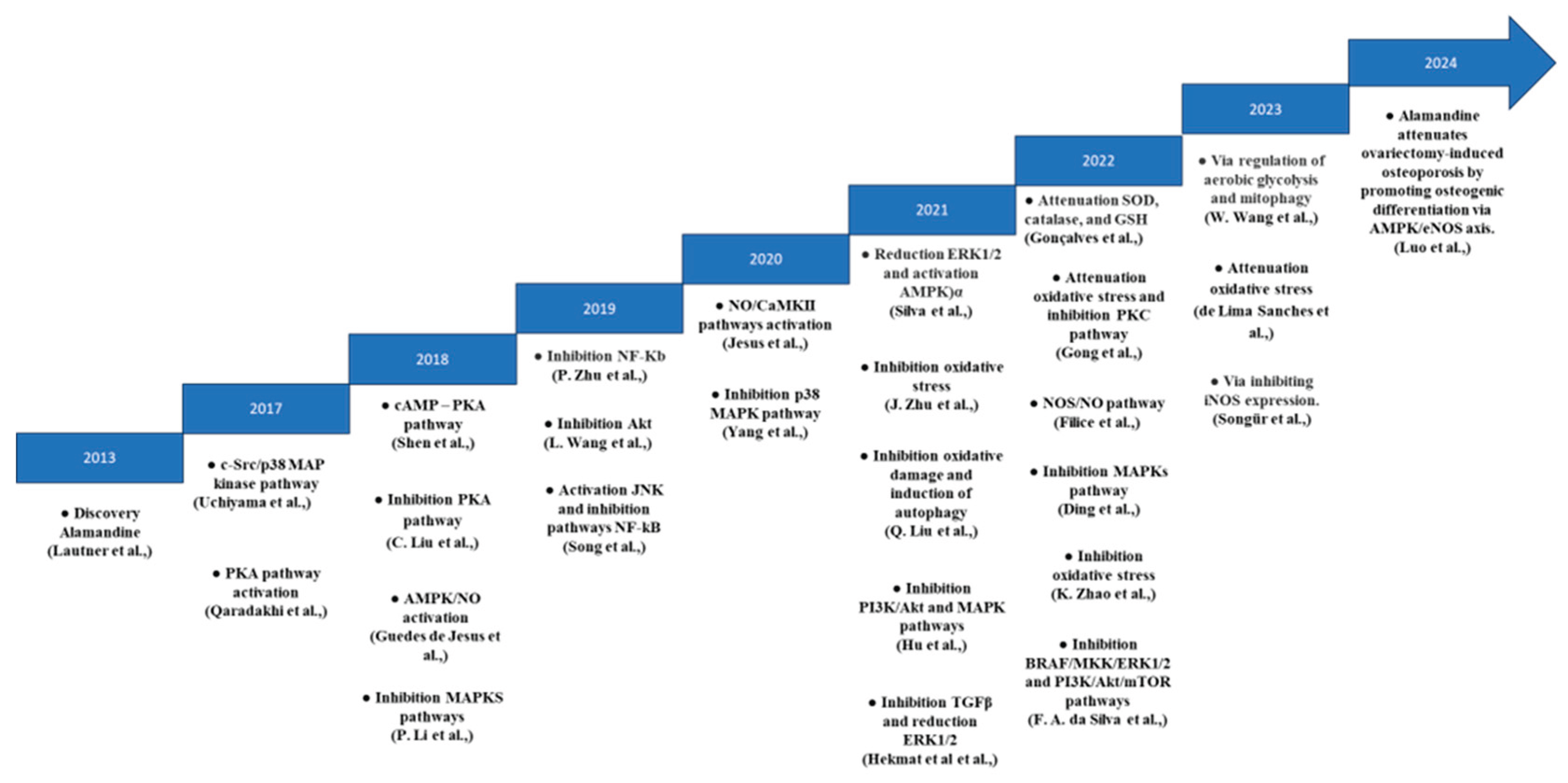

Figure 3 illustrates the timeline of ALA's mechanisms of action, beginning with its discovery in 2013.

4. Discussion

Identified in 2013, ALA, closely related to Ang-(1-7) and distinguished by a single amino acid [

34], dramatically alters its biological activity. ALA can be derived from angiotensin A through the action of ACE2 [

35] or by the decarboxylation of Ang-(1-7) [

36] (

Figure 4). This axis, comprising ACE2-Ang-(1-7)/ALA-Mas/MrgD, plays a critical role in counterbalancing the effects of Ang II, offering promising therapeutic avenues for various diseases.

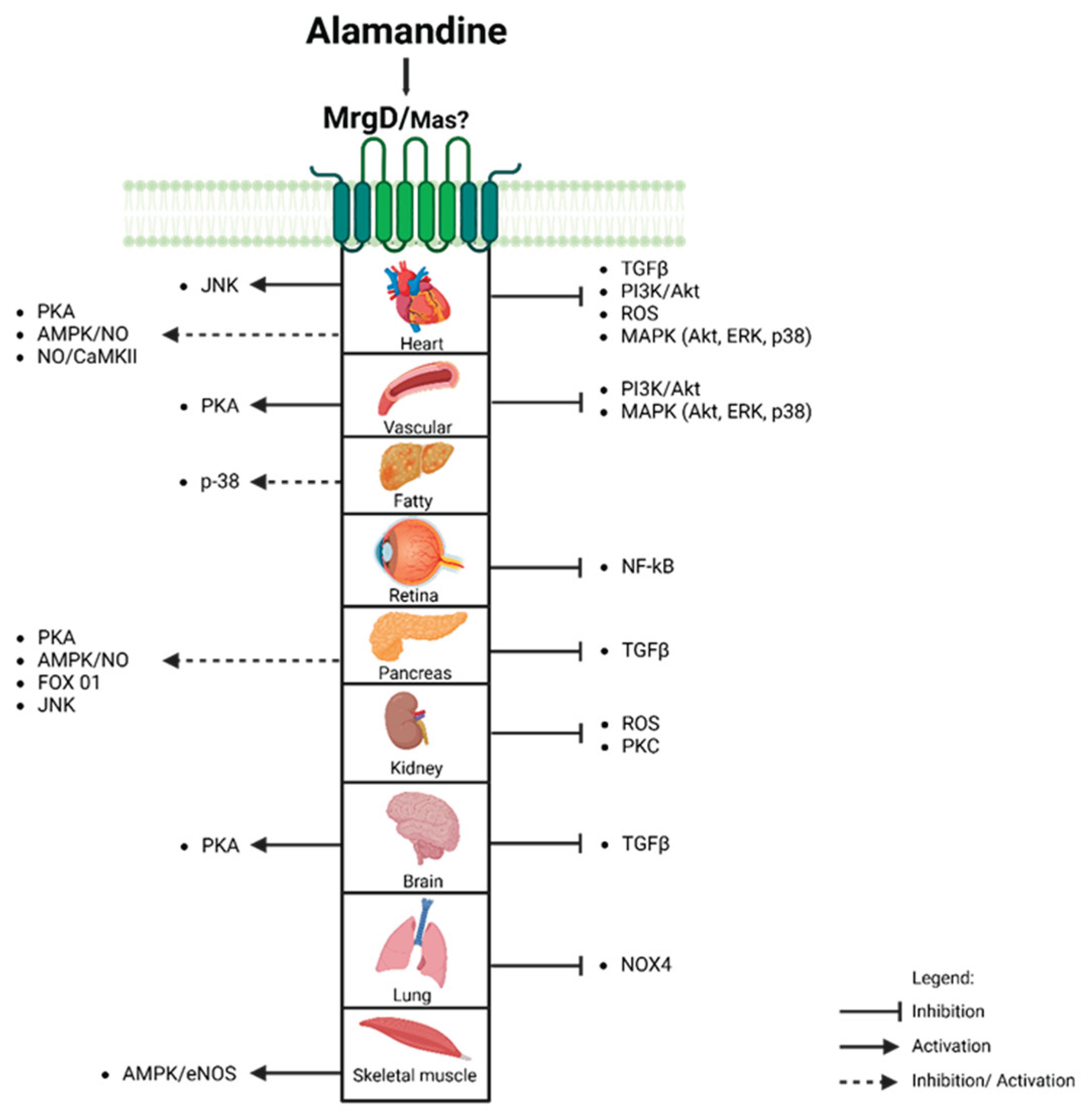

ALA interacts with widely expressed MrgD and Mas receptors. Activation of the ALA-MrgD axis is associated with beneficial effects, including vasodilation, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic actions. These effects are mediated by signaling pathways (

Figure 5), particularly Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) and Adenosine Monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), regulating NO production and cellular energy homeostasis. Understanding ALA's role in the RAS system opens new research opportunities for treating cardiovascular, renal, and oncological conditions.

4.1. Mas and Mrgd Receptors: ALA's (un)Specificity

The MrgD and Mas receptors are expressed in the dorsal root ganglia of the nervous system [

37] and various organs, including the heart [

6,

20,

38], brain [

39,

40,

41], lungs [

21], adipose tissue [

42], vascular endothelium, arterial smooth muscle cells [

43], and retina [

32]. ALA's affinity for the Mas receptor indicates a secondary receptor role [

36,

14].

The Mas and MrgD receptors may interact to form a functional complex. ALA binds to MrgD, promoting the dimerization of Mas and MrgD receptors, which leads to anti-inflammatory responses like reduced interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β secretion in lipopolysaccharide-activated THP-1 macrophages and M1 macrophages. Moreover, ALA promotes antiproliferative effects [

44].

The complexity of this interaction is evident in cells using compounds like as PD123319, D-PRO7-ANG-(1-7), and A779, exposing the challenge of targeting specific receptors [

45]. This suggests ALA's actions may involve MrgD and AT2 receptors, not just the Mas receptor [

1,

31,

46]. Furthermore, ALA's potential to promote MasR and MrgDR dimerization opens possibilities for enhanced anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects.

4.2. Mapks and Ampk Signaling Pathways

ALA-MrgD interaction in cardiomyocyte cultures enhances NO production [

6] and phosphorylates AMPK and LKB1, key regulators of energy and cardioprotection [

47]. AMPK activation is crucial for preventing cardiac injury progression to heart failure [

48,

49] and is linked to metabolic diseases [

50,

51], with bone tissue research supporting these findings [

22].

Emphasizing its cardiovascular benefits, ALA exhibits a broad anti-inflammatory effect by reversing the increased phosphorylation of Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), Protein Kinase B (Akt), Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38, reversing their increased activity in sepsis-associated renal injury [

18]. This inhibition involves the protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway [

20], underscoring cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent kinase's role in these processes [

52]. Inhibition of PKA by ALA induces cardiac remodeling [

53] and promotes vasodilation, as confirmed using KT5720, a PKA inhibitor [

23]. In fact, Shen et al.(2018) demonstrated that regulation of the PKA pathway is essential for ALA's effects in the brain.

Additionally, in ischemia-reperfusion (IRI), ALA treatment significantly lowers apoptosis in myocardial cells [

26], possibly by attenuating the inflammatory response through inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation [

26,

32]. This suppression reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [

18,

54], reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

32], and impacts myocardial infarction models due to pressure overload [

7]. It promotes protein kinase phosphorylation [

18,

54], affecting the balance between cellular survival/apoptosis.

The anti-inflammatory properties of ALA also extend to synovial fibroblasts, inhibiting the MAPK pathway, and leading to a reduction in inflammatory mediators associated with rheumatoid arthritis [

13]. Furthermore, ALA decreases matrix metalloproteinase-2, essential for TNF-alpha maturation and apoptosis control in cardiomyocytes [

55]. It also reduces TGF-β, preventing connective tissue fibrosis [

25,

56], and plays a crucial role in mitigating hypertrophic and fibrotic pathways by inhibiting phosphorylated forms in the MAPK pathways [

4].

Conversely, Ang II is known to promote phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, contributing to cardiac [

57], vascular fibrosis [

31,

58], cardiac stress, and hypertrophy [

59,

60]. The Ang-(1-7) and ALA axis improves aortic function (61), suggesting therapeutic benefits.

ALA also shows promise in controlling blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats by inhibiting PKA in the heart [

20]. It improves cardiac function in models of heart failure by attenuating TGF-β signaling and ERK 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation [

25]. In cardiomyocytes, PKA inhibition may reduce MAPK activation, affecting pathways like JNK and p38 [

4,

52,

62].

4.3. Nitric Oxide Production: The Therapeutic Role of ALA in Cardiovascular Health

ALA enhances endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity at serine 1177 and threonine 495, increasing NO release and highlighting its therapeutic potential for vasodilation and cardiovascular health [

23,

24,

53]. Studies on goldfish (Carassius auratus) show that ALA enhances cardiac contractility under normoxic conditions via the NOS/NO system, revealing its sensitivity to hypoxia and broad cardiac benefits [

14,

63].

Furthermore, Songür et al.(2023) and Hu et al.(2021) showed that ALA's anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and antipyretic properties protect against acute renal injury and endotoxemia by suppressing inducible NOS (iNOS) expression, highlighting its potential in mitigating inflammatory responses. In adipose tissue, ALA activates the MrgD receptor, triggering c-Src and increasing iNOS expression [

28], leading to NO production that may cause mitochondrial dysfunction and stimulate lipoprotein lipase activity, adversely affecting adipocytes [

64]. ALA's mechanisms are complex, showing anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing iNOS in acute renal injury, while potentially causing mitochondrial dysfunction in adipose tissue by increasing iNOS and NO production, highlighting its context-dependent biological impacts.

In a transgenic rat model with overexpressed renin, ALA enhances cardiomyocyte contractility via the NO/calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) pathway, initiating NO production and activating CaMKII in vascular smooth muscle cells [

19]. CaMKII phosphorylates the threonine 17 residue of phospholamban within the sarcoplasmic reticulum, increasing the activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and enhancing contractility [

19,

65].

4.4. Modulation of pi3k Enzyme Activity by ALA

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) enzyme family is central to numerous biological processes, including cell survival, apoptosis, and cardiac function [

66]. PI3K, along with its downstream effector Akt, regulates cell growth and apoptosis, playing a significant role in cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction associated with hypertension. In primary cardiac fibroblasts, ALA's interaction with the MrgD receptor inhibits Akt activation induced by Ang II, thereby reducing cardiac fibrosis [

29,

67,

68].

PI3K's role in cellular processes is broad. In addition to its role in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway is also relevant in various cell types, including tumor cells. For example, in cancer cell lines such as Mia Paca-2 and A549, ALA treatment shifts energy generation from anaerobic to aerobic processes, potentially slowing cancer growth. It inhibits the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, essential for cancer cell growth and survival, and induces the nuclear translocation of the FoxO1 protein, affecting various cellular processes [

11].

This pathway inhibition leads to the dephosphorylation and reduced activity of components like 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1, Akt1, and the mTOR receptor, as well as the BRAF/MKK/ERK1/2 signaling pathway, resulting in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. ALA reduces the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and its effectors, NIBAN2 and STMN1, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment [

11,

69].

Moreover, Wang et al. (2023) reported that ALA inhibits glycolysis in vitro, via MrgD axis and downregulates hexokinase 2 (HK2), reducing the impact of TGF-β1 on lung fibroblast (LF) [

30]. ALA decreases the NADPH Oxidase 4 levels and ROS generation in fibroblasts, which are known to contribute to the development of pulmonary fibrosis [

21]. Under anaerobic conditions, the glycolysis enhancement results in lactate formation from pyruvate [

70], creating a feedback loop that enhances LF activation and upregulates glycolysis pathway such as HK2 activity and the allosteric effector of phosphofructokinase-1 by 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) activity. In fact, HK2 and PFKFB3 are related to fibrosis development in several tissues: pulmonary [

71,

72], hepatic stellate cells [

73,

74], cardiac [

75], kidney tubular cells [

76] and renal fibroblast NRK-49F cells [

77].

Conversely, ALA/MrgD counter-regulates this loop, reducing hexokinase activity [

78], and decreasing glycolysis pathway [

30]. Moreover, previous study suggests that ALA-MrgD signaling downregulates the expression of HK2 and PFKFB3 genes, reinforcing the importance of changes in energetic metabolism during fibrosis and highlighting ALA's potential role in controlling this energetic shift [

30,

74,

76,

77,

79].

Mitophagy and glycolytic flux indicate a complex interaction with ALA [

80]. These insights highlight ALA's therapeutic potential by inhibiting LF activation via TGF-β1 and autophagy proteins (Parkin/LC3), while counteracting metabolic reprogramming in bleomycin-induced fibrosis by suppressing HK2, PFKFB3, Parkin, and LC3 activation [

30].

These findings show that in adipose tissue, ALA activates the NFκB and p38 MAP kinase pathways, which upregulate plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, a protein linked to adverse health outcomes [

81]. Uchiyama et al. (2017) demonstrated that a low dose of ALA (5.76 μg/kg) modulates leptin expression and secretion via the phospholipase C, cSrc, and p38 MAPK pathways. These findings reveal ALA's intricate metabolic effects, indicating the need for further investigation to fully understand its mechanisms and potential applications.

4.5. Alamandine and Oxidative Stress

Evidence suggests that ALA plays a crucial role in reducing cardiac fibrosis resulting from oxygen and glucose deprivation. This effect is supported by reductions in oxidative stress and ischemic injury [

7], as well as decreasing in apoptosis [

7,

82], which collectively lowers the risk of heart failure [

83]. ALA administration is associated with enhanced activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH), as demonstrated in the hippocampus of C57/Bl6 mice [

15]. Furthermore, De Lima Sanches et al. (2023) confirmed ALA's antioxidant properties, showing that oral administration effectively reduced superoxide anion (O2•-) and normalized nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 levels in the right carotid artery following transverse aortic constriction.

Oxidative stress has been related to caspase-3 signaling and cardiac apoptosis activation, particularly in the doxorubicin (DOX) model [

84]. Hekmat et al. (2021) demonstrated increased caspase-3 activation and apoptosis in DOX-exposed groups versus controls, while ALA significantly reduces both. Zhao et al. (2022) also demonstrated that ALA inhibits increases in collagen I, α-SMA, TGF-β, Bax/Bcl2, and the caspase-3/cleaved caspase-3 ratio, processes linked to cell death from oxygen-glucose deprivation in neonatal rat cardiac fibroblasts, highlighting ALA's cardiac protective effects [

7].

According to J. Zhu et al. (2021), in rats subjected to IRI, ALA treatment significantly increased SOD activity awhile reducing levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), NADPH oxidase activity, O2•- production, Nox expression, inflammation, and apoptosis. Additionally, Gong and colleagues found that in cases of renal sodium overload, ALA mitigated the decline in SOD and GSH activity, as well as the increase in MDA, 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine, and O2•- levels. This effect, likely mediated by inhibiting the protein kinase C signaling pathway [

16], underscores ALA’s protective role against oxidative stress and inflammation in renal function.

ALA shows promise, but limited research prevents definitive conclusions about its pathophysiological benefits. As the mechanisms underlying ALA's effects are not fully elucidated, it is crucial to interpret these findings with caution, acknowledging that they reflect our present understanding. Continued research is necessary to fully uncover ALA's therapeutic potential and its mechanisms of action.

5. Conclusions

Despite our limited knowledge, the discovery of Ang-(1-7) and ALA marks a significant advancement in our understanding of the RAS, introducing peptides with antagonistic actions. Numerous studies have sought to elucidate the benefits of this contemporary axis in various pathophysiological conditions, considering it counter-regulatory to the actions of Ang II, the potentially most active and studied peptide in the classical axis.

Thus, the recognition of these new peptides sparks a new debate and reinterpretation of the RAS. In the current knowledge, ALA acts by reducing oxidative stress and the inflammatory process, is involved in hypertrophic and fibrotic pathways, may interfere with glycolysis, and even affects the spread and growth of cancer cells. Studies reveal that ALA exhibits anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, anti-fibrotic, and metabolic effects through several mechanisms. Furthermore, various studies have shown that its administration, across a wide range of dosages, does not have detrimental effects. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that ALA presents impactful therapeutic potential, with the possibility of significantly contributing to improving people's health in the future.

However, it is important to note that ALA's discovery is recent, and many mechanisms require further elucidation as research continues. Thus far, part of what we know about its role in pathophysiology consists of the findings presented in this article. Moreover, the findings underscore the importance of considering dosage, tissue specificity, and the experimental conditions (in vivo vs. in vitro) when evaluating ALA's biological impacts. Further studies are necessary to elucidate ALA's diverse roles in health and disease, particularly in different pathophysiological contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R. and J.F.; methodology, F.M.S.; validation, A.T.S., J.F., L.B. and I.A.M.; formal analysis, A.F.K.V.; investigation, K.R.; data curation, A.T.S. and J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, K.R. and J.F; visualization, I.A.M.; supervision, K.R.; project administration, K.R., F.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

JF, ATS, IAM was supported by a doctoral fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Schematic representations were created with Biorender.com (QX27V8JO7G, QQ27V8L08X and UR27V8LF1B).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE |

Angiotensin-converting Enzyme |

| ACE2 |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| Akt |

Protein Kinase B |

| ALA |

Alamandine |

| ANG-(1-7) |

Angiotensin-(1-7) |

| Ang II |

Angiotensin II |

| AMPK |

Adenosine Monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| CAMKII |

Calmodulin-dependent kinase II |

| Dox |

Doxorubicin |

| eNOS |

Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| ERK1/2 |

Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1 and 2 |

| HK2 |

Hexokinase 2 |

| iNOS |

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IRI |

Ischemia-Reperfusion |

| JNK |

c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LF |

Lung Fibroblasts |

| MAPKs |

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| MrgD |

Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member D |

| NF-kB |

Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NO |

Nitric Oxide |

| NOS |

Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| O2•- |

Superoxide anion |

| PCC |

Population Concept and Context |

| PI3K |

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKA |

Protein kinase A |

| PKFB3 |

Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 |

| RAS |

Renin-angiotensin System |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| SHR |

Spontaneously hypertensive rats |

| SOD |

Superoxide Dismutase |

| STMN1 |

Stathmin 1 |

| TGFβ |

Transforming Growth Factor-β |

References

- Lautner RQ, Villela DC, Fraga-Silva RA, Silva N, Verano-Braga T, Costa-Fraga F, et al. Discovery and characterization of alamandine: A novel component of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res. 2013;112(8):1104–11. [CrossRef]

- Santos RA, Pesquero J, Chernicky CL, Greene LJ, Ferrario CM. Converting Enzyme Activity and Angiotensin Metabolism in the Dog Brainstem. Hypertension. 1988;11:153–157. [CrossRef]

- Schleifenbaum, J. Alamandine and its receptor mrgd pair up to join the protective arm of the renin-angiotensin system. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6(June):1–6. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Chen XR, Xu F, Liu C, Li C, Liu H, et al. Alamandine attenuates sepsis-associated cardiac dysfunction via inhibiting MAPKs signaling pathways. Life Sci. 2018;206(2017):106–16. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes RS, Netto MRT, Carvalho FB, Rigatto K. Alamandine: A promising treatment for fibrosis. Peptides (NY). 2022;157(May):170848. [CrossRef]

- Guedes de Jesus IC, Scalzo S, Alves F, Marques K, Rocha-Resende C, Bader M, et al. Alamandine acts via MrgD to induce AMPK/NO activation against ANG II hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;314(6):C702–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhao K, Xu T, Mao Y, Wu X, Hua D, Sheng Y, et al. Alamandine alleviated heart failure and fibrosis in myocardial infarction mice. Biol Direct. 2022;17(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Li Y, Lou A, Wang G zhen, Hu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Alamandine attenuates hepatic fibrosis by regulating autophagy induced by NOX4-dependent ROS. Clin Sci. 2020 Apr 17;134(7):853–69. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.globals.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, Brien KKO, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;(August 2016):467–73.

- da Silva FA, Rodrigues-Ribeiro L, Melo-Braga MN, Passos-Silva DG, Sampaio WO, Gorshkov V, et al. Phosphoproteomic studies of alamandine signaling in CHO-Mrgd and human pancreatic carcinoma cells: An antiproliferative effect is unveiled. Proteomics. 2022;22(17). [CrossRef]

- de Lima Sanches B, Souza-Neto F, de Alcântara-Leonídeo TC, Silva MM, Guatimosim S, Vieira MAR, et al. Alamandine attenuates oxidative stress in the right carotid following transverse aortic constriction in mice. Peptides (NY). 2023;(June). [CrossRef]

- Ding W, Miao Z, Feng X, Luo A, Tan W, Li P, et al. Alamandine, a new member of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), attenuates collagen-induced arthritis in mice via inhibiting cytokine secretion in synovial fibroblasts. Peptides (NY). 2022;154(May):170816. [CrossRef]

- Filice M, Mazza R, Imbrogno S, Mileti O, Baldino N, Barca A, et al. An ACE2-Alamandine Axis Modulates the Cardiac Performance of the Goldfish Carassius auratus via the NOS/NO System. Antioxidants. 2022;11(4):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves SCA, Bassi BLT, Kangussu LM, Alves DT, Ramos LKS, Fernandes LF, et al. Alamandine Induces Neuroprotection in Ischemic Stroke Models. Curr Med Chem. 2022;29(19):3483–98. [CrossRef]

- Gong J, Luo M, Yong Y, Zhong S, Li P. Alamandine alleviates hypertension and renal damage via oxidative-stress attenuation in Dahl rats. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hekmat AS, Navabi Z, Alipanah H, Javanmardi K. Alamandine significantly reduces doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40(10):1781–95. [CrossRef]

- Hu W, Gao W, Miao J, Xu Z, Sun L. Alamandine, a derivative of angiotensin-(1-7), alleviates sepsis-associated renal inflammation and apoptosis by inhibiting the PI3K/Ak and MAPK pathways. Peptides (NY). 2021;146(August):170627. [CrossRef]

- Jesus ICG, Mesquita TRR, Monteiro ALL, Parreira AB, Santos AK, Coelho ELX, et al. Alamandine enhances cardiomyocyte contractility in hypertensive rats through a nitric oxide-dependent activation of CaMKII. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020;318(4):C740–50. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Yang CX, Chen XR, Liu BX, Li Y, Wang XZ, et al. Alamandine attenuates hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in hypertensive rats. Amino Acids. 2018;50(8):1071–81. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Zheng B, Zhang Y, Huang W, Hong Q, Meng Y. Alamandine via MrgD receptor attenuates pulmonary fibrosis via nox4 and autophagy pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;99(9):885–93. [CrossRef]

- Luo W, Yao C, Sun J, Zhang B, Chen H, Miao J, et al. Alamandine attenuates ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis by promoting osteogenic differentiation via AMPK / eNOS axis. 2024;1–14. [CrossRef]

- Qaradakhi T, Matsoukas MT, Hayes A, Rybalka E, Caprnda M, Rimarova K, et al. Alamandine reverses hyperhomocysteinemia-induced vascular dysfunction via PKA-dependent mechanisms. Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;35(6):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Shen YH, Chen XR, Yang CX, Liu BX, Li P. Alamandine injected into the paraventricular nucleus increases blood pressure and sympathetic activation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Peptides (NY). 2018;103:98–102. [CrossRef]

- Silva MM, De Souza-Neto FP, De Jesus ICG, Gonçalves GK, De Carvalho Santuchi M, De Lima Sanches B, et al. Alamandine improves cardiac remodeling induced by transverse aortic constriction in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320(1):H352–63. [CrossRef]

- Song XD, Feng JP, Yang RX. Alamandine protects rat from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by activating JNK and inhibiting NF-κB. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;12(15):6718–26. [CrossRef]

- Songür HS, Kaya SA, Altınışık YC, Abanoz R, Özçelebi E, Özmen F, et al. Alamandine treatment prevents LPS-induced acute renal and systemic dysfunction with multi-organ injury in rats via inhibiting iNOS expression. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;960(November). [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama T, Okajima F, Mogi C, Tobo A, Tomono S, Sato K. Alamandine reduces leptin expression through the c-Src/p38 MAP kinase pathway in adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Liu C, Chen X, Li P. Alamandine attenuates long-term hypertension-induced cardiac fibrosis independent of blood pressure. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19(6):4553–60. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Zhang Y, Huang W, Yuan Y, Hong Q, Xie Z, et al. Alamandine/MrgD axis prevents TGF-β1-mediated fibroblast activation via regulation of aerobic glycolysis and mitophagy. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Wu X, Shen Y, Liu C, Li P, Kong X. Alamandine attenuates angiotensin II-induced vascular fibrosis via inhibiting p38 MAPK pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;883(November 2019):173384. [CrossRef]

- Zhu P, Verma A, Prasad T, Li Q. Expression and Function of Mas-Related G Protein-Coupled Receptor D and Its Ligand Alamandine in Retina. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57(1):513–27. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Qiu JG, Xu WT, Ma HX, Jiang K. Alamandine protects against renal ischaemia–reperfusion injury in rats via inhibiting oxidative stress. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2021;73(11):1491–502. [CrossRef]

- Villela DC, Passos-Silva DG, Santos RAS. Alamandine: A new member of the angiotensin family. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(2):130–4. [CrossRef]

- Jankowski V, Vanholder R, Van Der Giet M, Tölle M, Karadogan S, Gobom J, et al. Mass-spectrometric identification of a novel angiotensin peptide in human plasma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(2):297–302. [CrossRef]

- Tetzner A, Naughton M, Gebolys K, Eichhorst J, Sala E, Villacañas Ó, et al. Decarboxylation of Ang-(1–7) to Ala1-Ang-(1–7) leads to significant changes in pharmacodynamics. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:116–23. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara T, Harada M, Ogi K, Maruyama M, Fujii R, Tanaka H, et al. Identification of a G protein-coupled receptor specifically responsive to β-alanine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(22):23559–64. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira AC, Melo MB, Motta-Santos D, Peluso AA, Souza-Neto F, Da Silva RF, et al. Genetic deletion of the alamandine receptor mrgd leads to dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;316(1):H123–33. [CrossRef]

- Hami J, von Bohlen und Halbach V, Tetzner A, Walther T, von Bohlen und Halbach O. Localization and expression of the Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor member D (MrgD) in the mouse brain. Heliyon. 2021 Nov;7(11). [CrossRef]

- Jackson L, Eldahshan W, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Within the brain: The renin angiotensin system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):1–23. [CrossRef]

- Marins FR, Oliveira AC, Qadri F, Motta-Santos D, Alenina N, Bader M, et al. Alamandine but not angiotensin-(1–7) produces cardiovascular effects at the rostral insular cortex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2021;321(3):R513–21. [CrossRef]

- Cerri GC, Santos SHS, Bader M, Santos RAS. Brown adipose tissue transcriptome unveils an important role of the Beta-alanine/alamandine receptor, MrgD, in metabolism. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2023;114:109268. [CrossRef]

- Habiyakare B, Alsaadon H, Mathai ML, Hayes A, Zulli A. Reduction of angiotensin A and alamandine vasoactivity in the rabbit model of atherogenesis: Differential effects of alamandine and Ang(1-7). Int J Exp Pathol. 2014;95(4):290–5. [CrossRef]

- Rukavina NL, Silva MG, Erra FA, Karina AG, Mazzitelli L, Pineda M, et al. Alamandine, a protective component of the renin-angiotensin system, reduces cellular proliferation and interleukin-6 secretion in human macrophages through MasR – MrgDR heteromerization. 2024;229(June). [CrossRef]

- Assis AD, Mascarenhas FNA do P, Araújo F de A, Santos RAS, Zanon RG. Angiotensin-(1-7) receptor Mas antagonist (A779) influenced gliosis and reduced synaptic density in the spinal cord after peripheral axotomy. Peptides (NY). 2020;129(May):170329. [CrossRef]

- Marins FR, Oliveira AC, Qadri F, Motta-Santos D, Alenina N, Bader M, et al. Alamandine but not angiotensin-(1–7) produces cardiovascular effects at the rostral insular cortex. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2021;321(3):R513–21. [CrossRef]

- Takano APC, Diniz GP, Barreto-Chaves MLM. AMPK signaling pathway is rapidly activated by T3 and regulates the cardiomyocyte growth. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;376(1–2):43–50. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Beauloye C, Bertrand L, Horman S, Hue L. AMPK activation, a preventive therapeutic target in the transition from cardiac injury to heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90(2):224–33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang CX, Pan SN, Meng R Sen, Peng CQ, Xiong ZJ, Chen BL, et al. Metformin attenuates ventricular hypertrophy by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase-endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2011;38(1):55–62. [CrossRef]

- Hardie, DG. AMPK—Sensing Energy while Talking to Other Signaling Pathways. Cell Metab. 2014 Dec;20(6):939–52. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.

- Zaha VG, Young LH. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Regulation and Biological Actions in the Heart. Circ Res. 2012 Aug 31;111(6):800–14. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255505.

- Peng T, Lu X, Lei M, Feng Q. Endothelial nitric-oxide synthase enhances lipopolysaccharide-stimulated tumor necrosis factor-α expression via cAMP-mediated p38 MAPK pathway in cardiomyocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(10):8099–105. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Rababa’h A, Singh S, Suryavanshi S, Altarabsheh S, Deo S, McConnell B. Compartmentalization Role of A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins (AKAPs) in Mediating Protein Kinase A (PKA) Signaling and Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2014 Dec 24;16(1):218–29. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/16/1/218.

- Chen X, Li X, Zhang W, He J, Xu B, Lei B, et al. Activation of AMPK inhibits inflammatory response during hypoxia and reoxygenation through modulating JNK-mediated NF-κB pathway. Metabolism [Internet]. 2018 Jun;83(1):256–70. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0026049518300702.

- Shen J, O’Brien D, Xu Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 contributes to tumor necrosis factor alpha induced apoptosis in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347(4):1011–20. [CrossRef]

- Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K. TGF-β and the TGF-β Family: Context-Dependent Roles in Cell and Tissue Physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol [Internet]. 2016 May 2;8(5):a021873. Available online: http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/cshperspect.a021873.

- Zheng X, Yin Q, Lu H, Bai Y, Tian A, Yang Q, et al. A metabolite of Danshen formulae attenuates cardiac fibrosis induced by isoprenaline, via a NOX2/ROS/p38 pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(23):5573–85. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Díez R, Rodrigues-Díez R, Lavoz C, Rayego-Mateos S, Civantos E, Rodríguez-Vita J, et al. Statins inhibit angiotensin II/smad pathway and related vascular fibrosis, by a TGF-β-independent process. PLoS One. 2010;5(11). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Montezano AC, Burger D, Touyz RM. Angiotensin II, NADPH oxidase, and redox signaling in the vasculature. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(10):1110–20. [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Ginard B, Kajstura J, Anversa P, Leri A. A matter of life and death: cardiac myocyte apoptosis and regeneration. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003 May 15;111(10):1457–9. http://www.jci.org/articles/view/18611.

- Potthoff S, Stamer S, Grave K, Königshausen E, Sivritas S, Thieme M, et al. Chronic p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition improves vascular function and remodeling in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System [Internet]. 2016 Jul 12;17(3):147032031665328. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1470320316653284.

- Kostenko S, Shiryaev A, Dumitriu G, Gerits N, Moens U. Cross-talk between protein kinase A and the MAPK-activated protein kinases RSK1 and MK5. Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction. 2011;31(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Imbrogno S, Filice M, Cerra MC, Gattuso A. NO, CO and H2S: What about gasotransmitters in fish and amphibian heart? Acta Physiologica. 2018;223(1):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Jeon MJ, Leem J, Ko MS, Jang JE, Park HS, Kim HS, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of iNOS are responsible for the palmitate-induced decrease in adiponectin synthesis in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44(9):562–70.

- Beckendorf J, van den Hoogenhof MMG, Backs J. Physiological and unappreciated roles of CaMKII in the heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113(4):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Naga Prasad S, V. , Perrino C, Rockman HA. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in cardiac function and heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13(5):206–12. [CrossRef]

- Lin CY, Hsu YJ, Hsu SC, Chen Y, Lee HS, Lin SH, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist attenuates left ventricular hypertrophy and Akt-mediated cardiac fibrosis in experimental uremia. J Mol Cell Cardiol [Internet]. 2015;85(155):249–61. [CrossRef]

- Zhao QD, Viswanadhapalli S, Williams P, Shi Q, Tan C, Yi X, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 induces cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy through activating Akt/mTOR and NFκB signaling pathways. Circulation. 2015;131(7):643–55. [CrossRef]

- Roy SK, Srivastava RK, Shankar S. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways causes activation of FOXO transcription factor, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Mol Signal. 2010;5:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Lu L, Wang H, Liu X, Tan L, Qiao X, Ni J, et al. Pyruvate kinase isoform M2 impairs cognition in systemic lupus erythematosus by promoting microglial synaptic pruning via the β-catenin signaling pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):1–21.

- Zhang S, Sun L, Chen B, Lin S, Gu J, Tan L, et al. Telocytes protect against lung tissue fibrosis through hexokinase 2-dependent pathway by secreting hepatocyte growth factor. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2023;50(12):964–72. [CrossRef]

- Yin X, Choudhury M, Kang JH, Schaefbauer KJ, Jung MY, Andrianifahanana M, et al. Hexokinase 2 couples glycolysis with the profibrotic actions of TGF-β. Sci Signal. 2019;12(612). [CrossRef]

- Rho H, Terry AR, Chronis C, Hay N. Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Cell Metab. 2023;35(8):1406-1423. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Chen T, Lin Y, Gong J, Xu Q, et al. Caveolin-1 depletion attenuates hepatic fibrosis via promoting SQSTM1-mediated PFKL degradation in HSCs. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;204(April):95–107. [CrossRef]

- Wu R, Smeele KM, Wyatt E, Ichikawa Y, Eerbeek O, Sun L, et al. Reduction in hexokinase II levels results in decreased cardiac function and altered remodeling after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2011;108(1):60–9. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Li H, Jiang S, Fu D, Lu X, Lu M, et al. The glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 drives kidney fibrosis through promoting histone lactylation-mediated NF-κB family activation. Kidney Int. 2024;106(2):226–40. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Huo E, Cai Y, Zhang Z, Dong C, Asara JM, et al. PFKFB3-Mediated Glycolysis Boosts Fibroblast Activation and Subsequent Kidney Fibrosis. Cells. 2023;12(16). [CrossRef]

- Robey RB, Hay N, Robey RB, Hay N. Mitochondrial Hexokinases: Guardians of the Mitochondria. Cell Cycle. 2005;4101(5):654–8. [CrossRef]

- Zeng H, Pan T, Zhan M, Hailiwu R, Liu B, Yang H, et al. Suppression of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis restrains endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrotic response. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011 Jan 22;12(1):9–14. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm3028.

- Pandey M, Loskutoff DJ, Samad F. Molecular mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor-α-mediated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in adipocytes. The FASEB Journal [Internet]. 2005 Aug 31;19(10):1317–9. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1096/fj.04-3459fje.

- Kumar D, Jugdutt BI. Apoptosis and oxidants in the heart. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 2003;142(5):288–97. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Bing OHL, Long X, Robinson KG, Lakatta EG. Increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis during the transition to heart failure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;272(5 41-5). [CrossRef]

- Dash SK, Chattopadhyay S, Ghosh T, Dash SS, Tripathy S, Das B, et al. Self-assembled betulinic acid protects doxorubicin induced apoptosis followed by reduction of ROS-TNF-α-caspase-3 activity. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2015;72:144–57. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).