1. Introduction

Chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) and atrial fibrillation (AF) represent two of the most prevalent cardiovascular conditions worldwide, frequently coexisting in clinical practice and compounding morbidity and mortality risks when present together. Both entities share multiple pathophysiological pathways, including systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and neurohormonal activation, which contribute to both arrhythmogenic and atherothrombotic processes [

1,

2,

3]. Traditionally, clinical risk scores derived from AF populations, such as CHA₂DS₂VA or HAS-BLED, have been utilized primarily for estimating the risk of thromboembolic events or major bleeding in patients requiring anticoagulation [

4]. However, increasing evidence suggests that several components of these scores—including age, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus—also represent established risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) [

5].

Given this shared risk profile, it is plausible that AF-related clinical scores may carry additional value beyond their initial scope. Despite their widespread use, these scores have rarely been investigated as tools for identifying angiographic CAD severity. This represents a critical gap in clinical practice, especially considering the lack of simple, non-invasive methods to predict CAD burden in patients presenting with AF. Traditional CAD risk models often rely on laboratory markers or imaging techniques, which may not always be accessible during early assessment [

6].

In this context, repurposing widely used AF-related scores—such as CHA₂DS₂VA, HAS-BLED, and C₂HEST—for the early detection of significant coronary lesions may offer a pragmatic and accessible strategy for cardiovascular risk stratification. Their integration into clinical decision-making pathways could improve triage and resource allocation, particularly in settings with limited access to advanced diagnostics [

7]. Subsequently, several modified versions of the classical CHA₂DS₂VA score have emerged to improve predictive accuracy in broader cardiovascular contexts. Among these, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF incorporates hyperlipidemia, smoking, and family history to enhance atherosclerotic risk stratification [

8]. The CHA₂DS₂VA-RAF variant extends this further by integrating renal dysfunction (R) and the type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), accounting for renal contributions to cardiovascular risk. Similarly, the CHA₂DS₂VA-LAF version introduces left atrial enlargement (as the acronym L) and the type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), aiming to capture the atrial myopathy and structural cardiac changes associated with both AF progression and adverse cardiovascular outcomes [

9]. Furthermore, newer scores such as C₂HEST and HATCH, originally conceived to predict incident AF in other cardiovascular populations, integrate variables with established links to coronary disease, raising the possibility that their diagnostic utility may extend beyond arrhythmia prediction alone [

10].

The ability to non-invasively predict significant CAD using clinical data alone is of particular relevance in patients with AF and suspected CCS, especially given that this population may have atypical or silent ischemic presentations, and the yield of traditional non-invasive testing is often limited [

11]. Therefore, identifying simple, accessible clinical tools that could assist in early stratification of coronary risk holds substantial clinical value.

This proof-of-concept study aimed to explore the association between AF-derived clinical scores and the severity of coronary stenosis, in a cohort of patients with CCS and/or AF. We hypothesized that risk scores such as CHA₂DS₂VA, its extended variants (HSF, RAF, LAF), HAS-BLED, C₂HEST, and HATCH would differ according to the severity of coronary artery disease, highlighting their potential utility as diagnostic aids in cardiovascular risk stratification. Accordingly, we sought to evaluate the diagnostic utility of selected AF-related clinical scores in predicting significant CAD as determined by invasive coronary angiography and anatomical scoring systems, such as the Gensini and SYNTAX scores.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Patients and Investigation

We conducted a prospective proof-of-concept study that included 131 consecutively enrolled patients admitted with an indication for coronary angiography between January and June 2024. Eligible patients were over the age of 18, with or without a diagnosis of AF, who presented with signs suggestive of stable CAD. Inclusion criteria encompassed high-risk clinical profiles such as a strong family history of CAD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, or active smoking, along with either angina symptoms or positive results on non-invasive diagnostic tests (exercise stress test, stress echocardiography, myocardial scintigraphy), or documented coronary stenosis on coronary computed tomography angiography. All participants were required to provide written informed consent and demonstrate the capacity to understand the nature of the study. Although the same patient cohort was used as in our previously published study exploring galectin-3 and pentraxin-3 as biomarkers in S-CCS [

2], the current analysis focuses exclusively on the diagnostic value of widely used AF-related clinical risk scores in relation to coronary disease severity as assessed by invasive coronary angiography. In this context, we evaluated the relationship between AF-related scores and both Gensini and SYNTAX scores.

Exclusion criteria included patients under the age of 18, those who did not provide signed informed consent, individuals with acute myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease with creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min/1.73 m², hemodynamically significant valvular heart disease (greater than mild severity), advanced heart failure (NYHA class III or IV), as well as patients with significant thyroid or psychiatric disorders.

2.2. Clinical Evaluation and Data Collection

For all enrolled patients, comprehensive clinical, electrocardiographic (ECG), echocardiographic, and angiographic data were collected. Demographic data included age, sex, and smoking status. The presence of relevant comorbidities was documented, including history and type of AF, hypertension (HTN), heart failure (HF), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD) with moderate impairment (creatinine clearance between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m²), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), aortic atherosclerotic plaques, dyslipidemia, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), transient ischemic attack (TIA), and stroke. Chronic pharmacologic treatments were also recorded, including statins, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, oral anticoagulants, antiplatelet therapy, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Coronary angiography was performed using an Azurion 7 Philips system. The severity of coronary stenosis was visually evaluated and adjunctive physiological assessment using fractional flow reserve (FFR) or instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) were used, when it was necessary.

Clinical risk scores specified for AF (CHA₂DS₂, CHA₂DS₂VA, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, CHA₂DS₂VA-RAF, CHA₂DS₂VA-LAF, HAS-BLED, C₂HEST, and HATCH) were calculated prospectively at the time of admission, based on clinical and historical data routinely collected. These scores were computed using predefined criteria derived from current guidelines, and each calculation was independently performed by two trained investigators to ensure consistency. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus following review of the original clinical documentation. Their selection was based on clinical relevance, widespread use in AF management, and their incorporation into major cardiovascular guidelines. Anatomical and functional coronary scores derived from invasive coronary angiography reflecting CAD severity—Gensini and SYNTAX—were calculated after diagnostic coronary angiography was performed, using the angiographic data obtained. To ensure consistency and transparency in score application,

Table 1 summarizes the clinical variables and scoring criteria used for the calculation of each score included in the study.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed for all numerical variables, including mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values. For comparisons of quantitative variables between two groups, we employed the Student’s t-test, provided that normal distribution was confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. When comparing quantitative variables across more than two groups, we applied ANOVA (analysis of variance) if assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were satisfied (the latter verified via Levene’s test). In cases where variance homogeneity was violated, we used the Welch ANOVA test, which offers greater robustness. If the assumption of normality was not met, we utilized non-parametric tests: the Mann–Whitney U test for two-group comparisons and the Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple groups. When overall significance was identified in multiple-group comparisons, we conducted post hoc tests to determine specific group differences. For standard ANOVA, the Tukey–Kramer post hoc test was used to account for unequal group sizes. Following Welch’s ANOVA, the Games–Howell post hoc test was applied. For non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis comparisons, we used the Dunn post hoc test with Bonferroni adjustment. For categorical variables, intergroup comparisons were performed using the Chi-squared (χ²) test. Correlations between continuous variables were evaluated using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), with corresponding p-values and 95% confidence intervals to assess the direction and strength of associations.

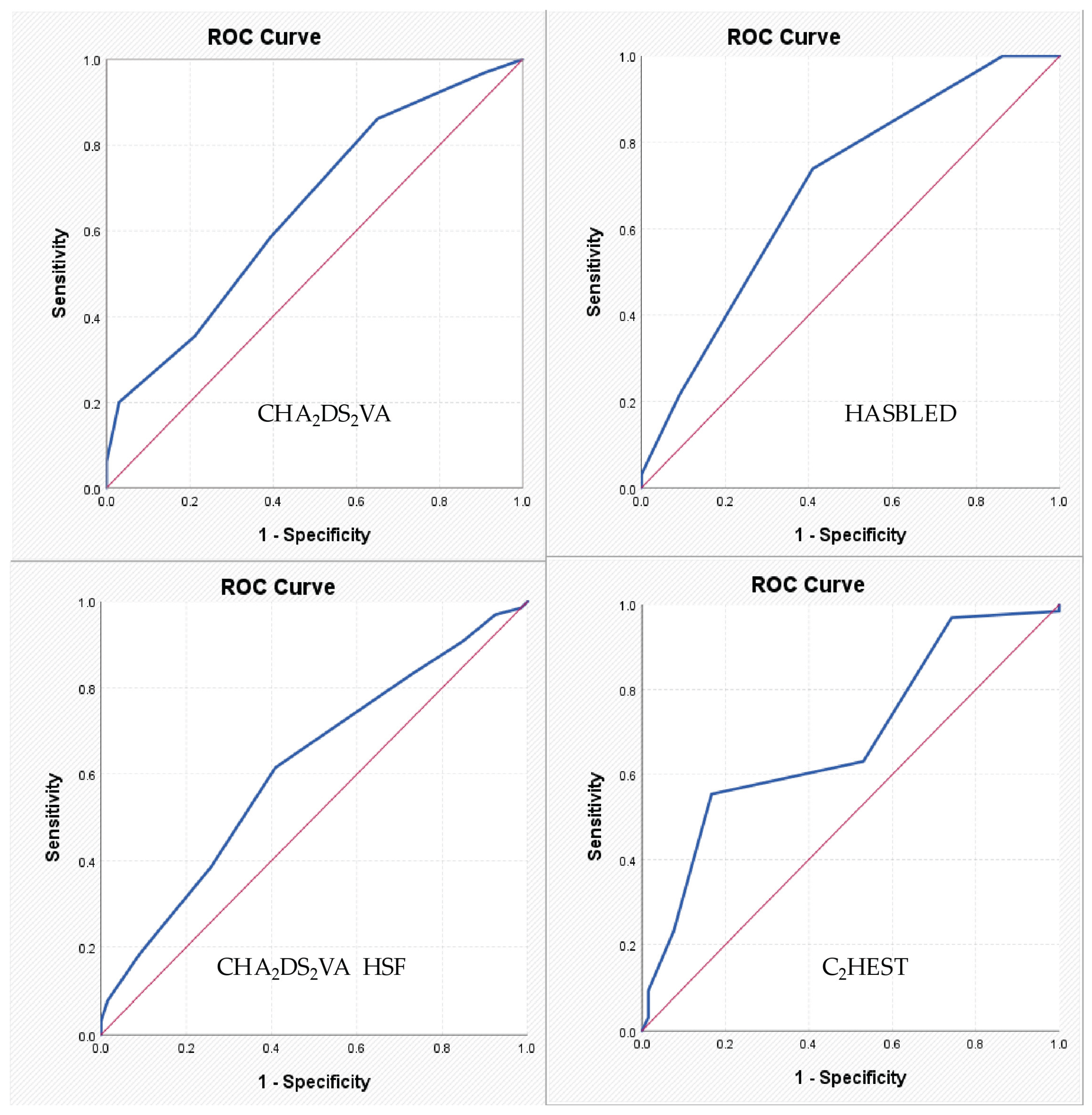

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, while values < 0.01 were considered highly significant. To assess the diagnostic performance of the evaluated clinical scores, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated and compared for each parameter.

2.4. Ethics

This proof-of-concept study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013. Upon admission, all participants provided written informed consent after receiving detailed explanations regarding the study objectives, procedures, and their rights as participants. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Gr. T. Popa” Iași (Approval No. 352/9 October 2023) and the Ethics Committee of St. Spiridon Emergency Clinical Hospital, Iași (Approval No. 75/11 September 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 131 patients were enrolled in the study and stratified into two subgroups based on coronary angiography findings:

Table 2 summarizes the general characteristics, comorbidities, treatment profiles, echocardiographic findings, and laboratory parameters of the study population.

Patients in the S-CCS group demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and reduced HDL-cholesterol levels, compared to those in the N-CCS group. However, no significant differences were observed between the groups regarding age, sex, family history of coronary artery disease, smoking status, hypertension, or obesity. A statistically significant difference was noted in cardiac rhythm, with sinus rhythm being more frequent in the S-CCS group (53.8%) compared to the N-CCS group (37.9%, p = 0.026). Conversely, atrial fibrillation (AF) was more prevalent in the N-CCS group (62.1%) than in the S-CCS group (46.2%), with a p-value of 0.067, suggesting a near-significant trend. The overall prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in the cohort was 9.9%, with a significantly higher occurrence in the S-CCS group (15.4%) compared to the N-CCS group (4.5%, p = 0.038).

None of echocardiographic parameters were statistically significant different in pa-tients with significant versus non-significant coronary lesions.

Regarding laboratory findings, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) was the only lipid marker that significantly differed between groups. Patients with significant coronary lesions exhibited notably significantly lower HDLc levels (mean: 40.88 mg/dL) compared to those with non-significant lesions (mean: 46.06 mg/dL), with a p-value of 0.004. This suggests that HDLc may serve as a potentially valuable biomarker in evaluating the extent of CAD.

Treatment regimens varied substantially across the two subgroups. Among patients diagnosed with significant coronary artery disease, 60 underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), while the remaining five underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and were managed with single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT). Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were co-administered with DAPT for gastroprotection, in line with clinical guidelines. Furthermore, the widespread prescription of nitrates and trimetazidine in the significant CAD group underscores adherence to evidence-based medical management. The higher prevalence of lipid-lowering therapy in this group further reflects a strong focus on secondary prevention strategies for high-risk atherosclerotic patients.

3.2. Potential Assessment of Coronary Lesion Severity Using AF-Related Risk Scores

To assess the diagnostic potential of AF-related clinical risk scores in predicting significant coronary artery stenosis, we compared multiple scoring systems between patients with significant and non-significant coronary lesions. The findings, summarized in

Table 3, illustrate the distribution of these scores—as well as the Gensini score—across patients with N-CCS and those with S-CCS, as determined by coronary angiography.

Unsurprisingly, the Gensini score, a well-validated indicator of coronary lesion burden, was markedly higher in the S-CCS group (mean: 46.83 ± 39.3) compared to the N-CCS group (mean: 5.07 ± 4.96), with a highly significant p-value (<0.001). This confirms the expected stratification in coronary severity between the two groups and serves as a reliable foundation for further comparative analysis of clinical risk profiles.

Among the AF-related scores, several showed significant differences between groups, pointing to a potentially meaningful link between AF risk and CAD severity:

The CHA₂DS₂VA score was significantly elevated in the S-CCS group (mean: 4.09 ± 1.656) compared to the N-CCS group (mean: 3.20 ± 1.338, p = 0.002). This suggests that patients with more advanced coronary lesions tend to accumulate more systemic vascular risk factors, thereby increasing their AF and thromboembolic risk.

The HAS-BLED score, used to estimate bleeding risk in anticoagulated AF patients, was also higher among S-CCS patients (1.98 ± 0.760) than in those with N-CCS (1.36 ± 0.835), with a statistically significant p-value (<0.001). This may reflect a greater prevalence of comorbidities and pharmacological interventions in the S-CCS group, which complicates antithrombotic management.

Additionally, the CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF variant, incorporating hyperlipidemia, smoking status and family history of premature CAD, showed a significant elevation in the S-CCS group (mean: 6.00 ± 1.854 vs. 5.26 ± 1.712, p = 0.021).

Of particular interest, the C₂HEST score, developed to predict incident AF in individuals without prior arrhythmia, also differed significantly between the two groups (3.49 ± 1.501 in S-CCS vs. 2.55 ± 1.279 in N-CCS, p < 0.001). This reinforces the hypothesis that more extensive coronary atherosclerosis is linked to a higher likelihood of developing AF, possibly via shared mechanisms such as atrial remodeling, inflammation, and myocardial ischemia.

In contrast, other scores—such as CHA₂DS₂, CHA₂DS₂VA-RAF, CHA₂DS₂VA-LAF, and HATCH—did not show statistically significant differences between groups. This may indicate limited sensitivity of these particular models for detecting angiographic CAD severity in this clinical context.

3.3. Diagnostic Performance of AF-Related Risk Scores in CCS

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the AF-related risk scores, we included in a binary logistic regression model the four scores that showed statistically significant differences between patients with and without S-CCS: CHA₂DS₂VA, HAS-BLED, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, and C₂HEST. The model was built using the Forward LR method. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test indicated that the model was viable, as the result was not statistically significant (p = 0.232). Initially, the model had a prediction accuracy for S-CCS of 50.4%; after incorporating the selected predictors, the accuracy increased to 71.8%, suggesting that the identified variables contribute meaningfully to diagnostic discrimination. The model explained 31.6% of the variance in the S-CCS diagnosis (Nagelkerke R² = 0.316) and demonstrated a sensitivity of 69.2% and a specificity of 74.2%. Although not exceptional, these performance metrics indicate a reasonable level of clinical utility.

Among the four tested predictors, HAS-BLED and C₂HEST scores emerged as statistically significant contributors to the model. Specifically, each one-point increase in the HAS-BLED score was associated with a 2.585-fold increase in the odds of having significant CAD, assuming the other predictors remained constant. Likewise, each one-point increase in the C₂HEST score was associated with a 1.564-fold increase in the odds of significant stenosis (

Table 4).

For the HAS-BLED score, the identified cut-off value was 1.50. The corresponding AUC coefficient was 0.694, indicating a relatively low discriminative power, with a sensitivity of 73.8% and a specificity of 59.1%. For the CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF score, the identified cut-off value was 5.50, with an AUC of 0.615, which also reflects a low discriminative power, with sensitivity of 61.5% and specificity of 59.1%. For the C₂HEST score, the identified cut-off value was 3.50, and the AUC was 0.682, again indicating a relatively low discriminative ability, but with a sensitivity of 55.4% and a specificity of 83.3%. For the remaining parameters, no satisfactory values were recorded (

Table 5,

Figure 1).

3.4. AF-Related Risk Scores: Correlations with Gensini Score

To further explore the potential utility of AF-related clinical scores in estimating the severity of CAD, we assessed the correlation between each score and the Gensini index. The results revealed a statistically significant moderate positive correlation between the HAS-BLED score and the Gensini score (r = 0.368, p < 0.0001), as well as between the CHA₂DS₂VA score and Gensini (r = 0.273, p = 0.0016). These findings suggest that as the clinical burden captured by these scores increases, so does the angiographically quantified severity of CAD. In contrast, the correlations for CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF and C₂HEST scores were weaker and did not reach statistical significance (r = 0.148 and r = 0.154, respectively), with 95% confidence intervals crossing zero. Although the trend remained positive, the lack of statistical significance suggests that these scores may have limited value as standalone predictors of coronary severity in this population. The results are described in

Table 6.

Finally, the confidence intervals for HAS-BLED (0.210 to 0.507) and CHA₂DS₂VA (0.106 to 0.425) further reinforce the robustness of their associations, as opposed to the broader, zero-inclusive intervals for CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF and C₂HEST. These results underscore that not all AF-related risk scores are equally informative in this context; rather, specific scores such as HAS-BLED and CHA₂DS₂VA may reflect overlapping cardiovascular risk factors relevant to both AF and CAD. Consequently, they may serve as practical tools in preliminary risk stratification, particularly when integrated with clinical and imaging data in patients presenting with CCS and/or AF.

3.5. AF-Related Risk Scores: Correlations with SYNTAX Score in Patients with S-CCS

In our study, the SYNTAX PCI and SYNTAX CABG scores were calculated exclusively for patients diagnosed with S-CCS. This methodological decision reflects the original purpose of the SYNTAX scoring system, which is to assist in determining the optimal revascularization strategy—PCI versus CABG—in patients with anatomically complex CAD. Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 7, including mean ± standard deviation and median with interquartile range (IQR).

Subsequently, we explored whether AF-related clinical risk scores—previously shown to correlate significantly with CAD severity in our cohort—also associate with the angiographic complexity of coronary disease as quantified by SYNTAX scoring. To this end, we conducted Pearson correlation analyses between the four clinical scores (CHA₂DS₂VA, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, HAS-BLED, and C₂HEST) and both SYNTAX PCI and CABG scores. The results are presented in

Table 8.

The analysis revealed statistically significant positive correlations between all clinical scores and both SYNTAX PCI and SYNTAX CABG values. Importantly, all p-values for the correlations were below the 0.05 threshold, even <0.001, indicating that the observed relationships are highly statistically significant and unlikely to be due to random variation. Furthermore, the calculated 95% confidence intervals for Pearson coefficients confirm the robustness of these associations, as none of them cross zero.

The HAS-BLED score demonstrated the strongest correlation with SYNTAX PCI (r = 0.423, p < 0.00001) and SYNTAX CABG (r = 0.430, p < 0.00001), suggesting that this score, although originally designed to predict bleeding risk, may also serve as a surrogate marker for CAD severity. This can be explained by the fact that HAS-BLED includes components closely related to vascular dysfunction (e.g., hypertension, renal impairment, age, previous stroke), which are also major contributors to coronary atherosclerosis.

The C₂HEST score showed a moderate and highly significant correlation with SYNTAX PCI (r = 0.389, p < 0.001) and SYNTAX CABG (r = 0.389, p < 0.001). As a score intended to predict the development of AF, its association with coronary lesion complexity supports the shared pathophysiologic mechanisms between atrial remodeling and atherosclerosis, including systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.

The CHA₂DS₂VA and CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF scores also exhibited statistically significant, albeit weaker, correlations with SYNTAX scores (r ≈ 0.29–0.30, p < 0.02). Their predictive components—age, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart failure, and vascular disease—are directly linked to both AF risk and CAD progression, justifying their moderate association.

Overall, this analysis supports the notion that AF-related clinical risk scores may provide valuable insight into the anatomical severity of CAD in patients with S-CCS. The particularly strong performance of HAS-BLED and C₂HEST scores suggests their utility may extend beyond their original indications, potentially aiding in risk stratification when angiographic data are not yet available.

4. Discussion

The current proof-of-concept study provides novel insight into the potential diagnostic utility of AF-related clinical scores—traditionally used for predicting thromboembolic or rhythm outcomes—in stratifying the severity of CAD in patients with CCS. Among the risk scores evaluated, HAS-BLED and C₂HEST emerged as independent predictors of significant coronary stenosis, and both demonstrated a statistically significant association with Gensini and SYNTAX scores, validated measures of angiographic CAD burden. These findings support the hypothesis that overlapping pathophysiological substrates between AF and CAD may be captured by multipurpose clinical scores, extending their utility beyond their original scope.

4.1. Shared Risk and Pathophysiological Mechanisms

The clinical overlap between AF and CAD is well-established, with shared risk factors including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia, and advancing age contributing to both disease entities [

12]. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction serve as central mechanisms linking atherogenesis to atrial remodeling, creating a bidirectional relationship between arrhythmogenesis and atherosclerosis. The present proof-of-concept study builds upon this conceptual framework by demonstrating that higher CHA₂DS₂VA, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, C₂HEST and HAS-BLED, scores that encapsulate many of these shared risk variables, are associated with a higher prevalence and severity of coronary stenosis [

14,

15].

4.2. CHA₂DS₂VA and CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF: Beyond Stroke Risk

The CHA₂DS₂VA score, the new variant of the well-established CHA₂DS₂VASc score, was initially designed to assess thromboembolic risk in patients with AF. However, it incorporates clinical variables such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and vascular disease—all of which are independently associated with CAD. In our study, this score showed a significant association with the severity of angiographically confirmed CAD, suggesting its potential utility in broader cardiovascular risk stratification beyond AF populations.

Several prior studies have echoed these findings. For instance, Modi et al. investigated a modified version of the score, termed CHA₂DS₂VASc-HSF, which includes additional risk factors—Hyperlipidemia, Smoking, and Family history of premature CAD. Their study of 2,976 patients undergoing coronary angiography demonstrated that the CHA₂DS₂VASc-HSF score had a strong positive correlation with both the presence and severity of CAD, with a statistically significant association (p < 0.001). This variant improved the ability to predict significant coronary lesions, underscoring the relevance of incorporating lifestyle and genetic predispositions in cardiovascular risk tools [

16].

Moreover, a study by Cetin et al. demonstrated that the CHA₂DS₂VASc score positively correlates with the severity and complexity of CAD in patients undergoing coronary angiography. They found that higher CHA₂DS₂VASc scores were associated with increased SYNTAX scores, indicating more complex coronary lesions [

17]. Furthermore, a study by Tran et al. introduced the CHA₂DS₂VASc-HS score, which adds hyperlipidemia and smoking to the original CHA₂DS₂VASc components. Their findings revealed a strong correlation between higher CHA₂DS₂VASc-HS scores and increased Gensini score, suggesting that this modified score may be a useful tool for predicting CAD severity [

18].

In summary, our findings, supported by existing literature, indicate that both the CHA₂DS₂VA and CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF scores, though originally developed for stroke risk in AF management, have broader applicability in assessing CAD severity. These scores, based on readily available clinical parameters, could serve as valuable tools in the early identification and risk stratification of patients with significant CAD.

4.3. HAS-BLED Score: A Marker for CAD Risk?

The HAS-BLED score, originally developed to estimate the risk of major bleeding in patients with AF undergoing anticoagulation therapy, includes clinical parameters such as hypertension, abnormal liver or renal function, stroke history, bleeding history, labile INR, age, and concomitant use of drugs or alcohol. While its primary application is in bleeding risk stratification, emerging evidence suggests that the HAS-BLED score may also reflect the overall burden of systemic vascular disease, thereby serving as a potential marker for CAD severity.

In our study, higher HAS-BLED scores were significantly associated with greater CAD severity, as assessed by the Gensini and SYNTAX scores. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that the components of the HAS-BLED score are closely linked to cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes. For instance, a study by Konishi et al. evaluated the predictive value of the HAS-BLED score in patients undergoing PCI with drug-eluting stents. The study found that a high HAS-BLED score (≥3) was independently associated with increased risks of major bleeding and all-cause mortality over a median follow-up of 3.6 years, regardless of the presence of AF. This suggests that the HAS-BLED score captures comorbidities and clinical features that contribute to both bleeding and ischemic risks [

19].

Similarly, Castini et al. investigated the utility of the HAS-BLED score for risk stratification in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) without AF. Their study demonstrated that higher HAS-BLED scores were associated with increased in-hospital and post-discharge bleeding events, as well as higher mortality rates. The discriminative performance of the HAS-BLED score for predicting these outcomes was moderate to good, indicating its potential applicability beyond bleeding risk assessment in AF patients [

20].

Further evidence supporting the utility of the HAS-BLED score in the stable CAD population is provided by Yildirim et al., who evaluated its performance in predicting hemorrhagic events in patients with chronic CAD receiving antithrombotic therapy. Although the primary focus was on bleeding risk, their findings underscore the applicability of HAS-BLED in this clinical context, demonstrating that it outperformed the CRUSADE score in forecasting major bleeding complications. This is particularly relevant, as many of the components included in HAS-BLED—such as hypertension, renal dysfunction, and prior stroke—are also well-established contributors to CAD progression and adverse outcomes. The study’s emphasis on stable CAD patients highlights that HAS-BLED may not only serve as a bleeding risk tool in anticoagulated populations, but also offer insight into the overall clinical complexity and frailty of CAD patients, further supporting its broader relevance in cardiovascular risk assessment [

21].

Taken together, these data support the concept that the HAS-BLED score—though originally designed for assessing bleeding risk in anticoagulated AF patients—may reflect broader vascular risk, including the presence and severity of CAD. Its components overlap substantially with known predictors of adverse cardiovascular events. Therefore, in the setting of CCS, particularly in patients with AF or multiple comorbidities, the HAS-BLED score may serve as a pragmatic and clinically valuable tool not only for anticipating bleeding risk but also for identifying individuals with potentially advanced atherosclerotic disease.

4.4. C₂HEST Score: Predicting More than AF

The C₂HEST score, originally developed to predict the risk of incident AF, comprises six clinical variables: Coronary artery disease (CAD) or Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1 point each), Hypertension (1 point), Elderly (age ≥75 years, 2 points), Systolic heart failure (2 points), and Thyroid disease (hyperthyroidism, 1 point). While its primary application has been in AF risk stratification, emerging evidence suggests that the C₂HEST score may also serve as a marker for broader cardiovascular risk, including the severity of CAD [

22].

In our study, higher C₂HEST scores were significantly associated with greater CAD severity, as assessed by the Gensini and SYNTAX scores. This finding aligns with the components of the C₂HEST score, many of which are established risk factors for atherosclerosis and CAD progression. Supporting this, a study by Li et al. demonstrated that the C₂HEST score effectively predicted incident AF in a large cohort of post-ischemic stroke patients, with a C-index of 0.734, outperforming other risk scores such as the CHA₂DS₂VASc and Framingham risk scores. Although this study focused on AF prediction, the strong performance of the C₂HEST score underscores its potential utility in assessing overall cardiovascular risk [

22].

Moreover, a study by Rola et al. evaluated the utility of the C₂HEST score in predicting clinical outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without CAD. The study found that higher C₂HEST scores were associated with increased in-hospital, 3-month, and 6-month mortality rates, particularly in the CAD cohort. Specifically, in the CAD group, in-hospital mortality reached 43.06% in the high-risk C₂HEST stratum, compared to 26.92% in the non-CAD group. These findings suggest that the C₂HEST score captures comorbidities and clinical features that contribute to both bleeding and ischemic risks, extending its utility beyond AF prediction to broader cardiovascular risk assessment [

23].

These findings collectively indicate that the C₂HEST score, although originally intended for AF prediction, captures a cluster of clinical features that overlap substantially with the risk profile of patients prone to significant CAD. In our cohort, patients with S-CCS exhibited significantly higher C₂HEST scores compared to those with non-significant lesions, suggesting that this score may serve as a pragmatic tool for early recognition of more advanced coronary atherosclerosis. As such, the C₂HEST score could offer additional diagnostic value in identifying individuals at higher risk of severe coronary stenosis, guiding in the selection of patients for the invasive coronarography.

4.5. Clinical Implications, Study Limitations and Future Directions

The potential repurposing of AF-related clinical scores such as CHA₂DS₂VA, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, HAS-BLED, and C₂HEST for evaluating the severity of CAD introduces a pragmatic and accessible strategy for early cardiovascular risk stratification. These scores, based on widely available clinical parameters—such as age, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and prior vascular disease—offer low-cost, easy-to-use tools that can support decision-making in routine clinical practice.

A practical implication of our findings lies in the potential use of AF-related scores as a rapid, non-invasive screening tool in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of CAD. In emergency or outpatient settings where immediate access to advanced imaging is limited, clinical scores like HAS-BLED or C₂HEST could help identify high-risk patients who warrant early referral for invasive coronary assessment. Their simplicity and reliance on routinely collected clinical parameters allow for immediate bedside application without the need for additional laboratory or imaging data. This could streamline diagnostic pathways, reduce unnecessary testing, and optimize resource allocation.

Compared to traditional CAD risk estimation tools such as the Framingham Risk Score or the SCORE system, AF-derived scores offer a different angle of assessment—focusing more on cumulative systemic comorbidity than solely on lipid profiles or smoking status. While conventional models remain valid for long-term cardiovascular risk prediction, they may underperform in acute settings or in patients with atypical presentations, such as those with arrhythmias. The AF-based scores capture overlapping cardiovascular vulnerabilities (e.g., age, hypertension, heart failure), which may indirectly reflect underlying coronary disease burden and merit further validation in comparative studies.

It is also important to consider whether the performance of these repurposed scores may vary across different subgroups, such as sex, ethnicity, or comorbidity profiles. For instance, younger patients with non-valvular AF or those without overt cardiovascular symptoms may have deceptively low scores despite harboring significant coronary lesions. Similarly, sex-specific pathophysiological mechanisms could affect score sensitivity, given that women often present with atypical symptoms and microvascular disease. Although our study did not include stratified analyses, these factors should be addressed in future multicenter trials to refine risk stratification tools across diverse populations.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted in a single-center setting, which may limit the external generalizability of the findings. Variations in patient demographics, clinical practices, and resource availability across institutions could influence the performance and applicability of these scores in other settings. Second, the overall sample size, although suitable for exploratory analysis, was relatively modest. With 131 patients divided into two balanced groups (N-CCS and S-CCS), the statistical power to detect small but clinically relevant differences may have been insufficient, especially for borderline significant parameters.

Moreover, while these AF-derived scores demonstrated associations with CAD severity, they were not specifically designed for this purpose. Their predictive accuracy for coronary atherosclerosis is inherently constrained by their original focus on arrhythmia or bleeding risk. Consequently, they should be regarded as adjunctive tools that support—but not to replace—more specialized diagnostic approaches for CAD such as coronary computed tomography angiography or invasive coronarography. Subsequently, the study did not include longitudinal follow-up or clinical outcome tracking. As a result, the predictive performance of these risk scores for adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction, need for revascularization, hospital readmissions, or death (MACE) could not be evaluated.

Future research should focus on several key areas. Firstly, the validation of these scores in larger, multicenter cohorts with diverse patient populations is essential to confirm their utility in real-world settings. Such studies should explore their predictive performance across age groups, sexes, and different clinical presentations of CCS. Secondly, the development of hybrid or composite models that incorporate elements from multiple scoring systems, alongside biomarkers and imaging findings, could yield more robust and individualized risk stratification tools for patients with suspected CAD.

Finally, while originally designed for arrhythmia and bleeding risk assessment in AF, clinical scores such as CHA₂DS₂VA, CHA₂DS₂VA-HSF, HAS-BLED, and C₂HEST demonstrate potential for broader cardiovascular application. Their judicious use—alongside standard diagnostics—may aid in identifying patients with significant CAD and optimizing early clinical management, particularly in resource-limited or primary care settings.

5. Conclusions

Our proof-of-concept study demonstrates that clinical risk scores primarily developed for AF management—particularly HAS-BLED and C₂HEST—may be significantly associated with angiographic coronary artery disease severity. These scores showed meaningful correlations with Gensini and SYNTAX scores, reinforcing their potential utility in the early stratification of patients with CCS.

Given their simplicity, low cost, and broad clinical familiarity, these scores may serve as a rapid triage method to identify patients with suspected CCS who are most likely to benefit from early invasive evaluation. While these findings are promising, they should be interpreted with caution, and further multicenter studies with larger cohorts and prospective outcome tracking are necessary to validate the diagnostic and prognostic value of these scores in CAD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-F.O. and M.F.; methodology, P.C.M., M.G. and S.D.D.; software, P.C.M., M.G. and S.D.D.; validation, O.M., A.B. and R.M.; formal analysis, A.M.B., A.P.; and R.M.; investigation, A.M.B., D.-E.F. and A.V.; resources, O.M., A.B., and A.V.; data curation, M.M.; D.I.; and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-F.O.; writing—review and editing, A.-F.O. and M.F.; visualization, A.-F.O., D.-E.F. and M.F.; supervision, I.-I.C.-E., M.F. and D.M.T.; project administration, I.-I.C.-E., M.M., and D.M.T.; funding acquisition, D.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is a study from a PhD thesis of Alexandru- Florinel Oancea, and it received research funding from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Gr. T. Popa”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Gr. T. Popa” (no. 352/9 October 2023) and of the St. Spiridon Emergency Clinical Hospital (no. 75/11 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are available within the article. The first author has all data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oancea, A.F.; Jigoranu, R.A.; Morariu, P.C.; Miftode, R.-S.; Trandabat, B.A.; Iov, D.E.; Cojocaru, E.; Costache, I.I.; Baroi, L.G.; Timofte, D.V.; et al. Atrial Fibrillation and Chronic Coronary Ischemia: A Challenging Vicious Circle. Life 2023, 13, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A.-F.; Morariu, P.C.; Godun, M.; Dobreanu, S.D.; Jigoranu, A.; Mihnea, M.; Iosep, D.; Buburuz, A.M.; Miftode, R.S.; Floria, D.-E.; et al. Galectin-3 and Pentraxin-3 as Potential Biomarkers in Chronic Coronary Syndrome and Atrial Fibrillation: Insights from a 131-Patient Cohort. IJMS 2025, 26, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floria, M.; Oancea, A.F.; Morariu, P.C.; Burlacu, A.; Iov, D.E.; Chiriac, C.P.; Baroi, G.L.; Stafie, C.S.; Cuciureanu, M.; Scripcariu, V.; et al. An Overview of the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Landiolol (an Ultra-Short Acting Β1 Selective Antagonist) in Atrial Fibrillation. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Pisters, R.; Lane, D.A.; Crijns, H.J.G.M. Refining Clinical Risk Stratification for Predicting Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation Using a Novel Risk Factor-Based Approach. Chest 2010, 137, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.F. Established Risk Factors and Coronary Artery Disease: The Framingham Study. American Journal of Hypertension 1994, 7, 7S–12S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batta, A.; Hatwal, J.; Batta, A.; Verma, S.; Sharma, Y.P. Atrial Fibrillation and Coronary Artery Disease: An Integrative Review Focusing on Therapeutic Implications of This Relationship. World J Cardiol 2023, 15, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, G.D.; Lip, G.Y.H. Applying Clinical Risk Scores in Real-World Practice. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2024, 84, 2154–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, R.; Patted, S.V.; Halkati, P.C.; Porwal, S.; Ambar, S.; Mr, P.; Metgudmath, V.; Sattur, A. CHA2DS2-VASc-HSF Score – New Predictor of Severity of Coronary Artery Disease in 2976 Patients. International Journal of Cardiology 2017, 228, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Zhang, J. External Validation and Comparison of CHA2DS2–VASc-RAF and CHA2DS2–VASc-LAF Scores for Predicting Left Atrial Thrombus and Spontaneous Echo Contrast in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2022, 65, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-S.; Lin, C.-L. Prediction of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation for General Population in Asia: A Comparison of C2HEST and HATCH Scores. International Journal of Cardiology 2020, 313, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuuti, J.; Ballo, H.; Juarez-Orozco, L.E.; Saraste, A.; Kolh, P.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Jüni, P.; Windecker, S.; Bax, J.J.; Wijns, W. The Performance of Non-Invasive Tests to Rule-in and Rule-out Significant Coronary Artery Stenosis in Patients with Stable Angina: A Meta-Analysis Focused on Post-Test Disease Probability. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 3322–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oancea, A.-F.; Morariu, P.; Buburuz, A.; Miftode, I.-L.; Miftode, R.; Mitu, O.; Jigoranu, A.; Floria, D.-E.; Timpau, A.; Vata, A.; et al. Spectrum of Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Its Relationship with Atrial Fibrillation. JCM 2024, 13, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepine, C.J. ANOCA/INOCA/MINOCA: Open Artery Ischemia. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice 2023, 26, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladding, P.A.; Legget, M.; Fatkin, D.; Larsen, P.; Doughty, R. Polygenic Risk Scores in Coronary Artery Disease and Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ 2020, 29, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michniewicz, E.; Mlodawska, E.; Lopatowska, P.; Tomaszuk-Kazberuk, A.; Malyszko, J. Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Coronary Artery Disease - Double Trouble. Adv Med Sci 2018, 63, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, R.; Patted, S.V.; Halkati, P.C.; Porwal, S.; Ambar, S.; Mr, P.; Metgudmath, V.; Sattur, A. CHA2DS2-VASc-HSF Score – New Predictor of Severity of Coronary Artery Disease in 2976 Patients. International Journal of Cardiology 2017, 228, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M.; Cakici, M.; Zencir, C.; Tasolar, H.; Baysal, E.; Balli, M.; Akturk, E. Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease Severity Using CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc Scores and a Newly Defined CHA2DS2-VASc-HS Score. The American Journal of Cardiology 2014, 113, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.-V.; Nguyen, K.-D.; Nguyen, K.-D.; Huynh, A.-T.; Tran, B.-L.-T.; Ngo, T.-H. Predictive Performance of CHA2DS2-VASc-HS Score and Framingham Risk Scores for Coronary Disease Severity in Ischemic Heart Disease Patients with Invasive Coronary Angiography. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2023, 27, 7629–7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Miyauchi, K.; Tsuboi, S.; Ogita, M.; Naito, R.; Dohi, T.; Kasai, T.; Tamura, H.; Okazaki, S.; Isoda, K.; et al. Impact of the HAS-BLED Score on Long-Term Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. The American Journal of Cardiology 2015, 116, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castini, D.; Persampieri, S.; Sabatelli, L.; Erba, M.; Ferrante, G.; Valli, F.; Centola, M.; Carugo, S. Utility of the HAS-BLED Score for Risk Stratification of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Heart Vessels 2019, 34, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Uku, O.; Bilen, M.; Secen, O. Performance of HAS-BLED and CRUSADE Risk Scores for the Prediction of Haemorrhagic Events in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. CVJA 2019, 30, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bisson, A.; Bodin, A.; Herbert, J.; Grammatico-Guillon, L.; Joung, B.; Wang, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Fauchier, L. C2 HEST Score and Prediction of Incident Atrial Fibrillation in Poststroke Patients: A French Nationwide Study. JAHA 2019, 8, e012546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rola, P.; Doroszko, A.; Trocha, M.; Gajecki, D.; Gawryś, J.; Matys, T.; Giniewicz, K.; Kujawa, K.; Skarupski, M.; Adamik, B.; et al. The Usefulness of the C2HEST Risk Score in Predicting Clinical Outcomes among Hospitalized Subjects with COVID-19 and Coronary Artery Disease. Viruses 2022, 14, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).