1. Introduction

Cancer cells employ metabolic reprogramming to regulate metabolism, providing sufficient energy and substrates while maintaining redox balance and supporting rapid cell proliferation [

1,

2]. Dysregulated glucose metabolism is a hallmark of metabolic reprogramming in many cancer cells, leading to an increased rate of glucose consumption compared to normal cells [

3,

4]. Most of the glucose is secreted as lactate rather than being oxidized in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Consequently, dysregulated glucose metabolism in rapidly proliferating cancer cells fails to produce adequate amounts of ATP or the intermediates required for biosynthesis [

5,

6]. An alternative energy source is amino acids, particularly glutamine, the most abundant amino acid in mammals [

7,

8]. Cancer cells rely more heavily on glutamine compared to other amino acids and upregulate glutamine metabolism to meet the bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands of continuous growth [

9]. The primary purpose of glutamine metabolism is to generate energy for cell proliferation by providing a carbon source [

10]. Glutamine enters the cell via the alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2) and is metabolized in the mitochondria by glutaminase (GLS) into glutamate. Glutamate is then converted into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), mainly through glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (GLUD1), producing ATP in the TCA cycle [

11,

12]. Another function of glutamine is to provide a nitrogen source for the synthesis of nucleotides and other non-essential amino acids. Additionally, glutamate can be used to generate glutathione, an antioxidant that serves as a redox buffer against oxidative stress [

13].

As a crucial epigenetic regulatory mechanism, histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) regulate numerous biological processes, including gene transcription, chromatin dynamics, and development [

14]. Histone modifications can regulate genomic DNA by modulating it into euchromatic regions (which are transcriptionally active) or into inactive heterochromatic regions (which are transcriptionally repressed), thereby controlling gene expression as a class of gene expression-regulating PTMs [

15,

16]. Histone modifications regulate chromatin structure and the enrichment of DNA and transcription regulatory proteins in chromatin, playing a crucial role in regulating DNA replication, repair, and gene expression [

17,

18]. More than 16 types of histone modifications, including acetylation, methylation, and crotonylation, occur on the N-terminal tails and globular domains of core histones [

19,

20,

21]. Histone crotonylation is a novel and broadly impactful histone modification that has been widely confirmed to play roles in various physiological and pathological processes, making it a hot topic and frontier area of research [

22,

23,

24]. In 2023, a significant study revealed that in glioblastoma, glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH) mediates lysine metabolism reprogramming, leading to the production of crotonyl-CoA, which increases the level of histone crotonylation and affects interferon signaling and CD8+ T cell infiltration [

25]. This study for the first time uncovered the key role of crotonylation in immune evasion, while also identifying the critical function of GCDH in this process [

25]. However, the role of GCDH in breast cancer has not been elucidated. In this study, we determined how GCDH participate in the regulation of breast cancer growth and energy metabolism by employing the in vitro and in vivo model, followed by mechanistic studies to explore the regulatory mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

The breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were sourced from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). For their maintenance, both MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium, which was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA). The cells were cultivated under controlled environmental conditions in a 5% CO2 incubator (Thermo, Waltham, USA), with the temperature maintained at 37°C and the humidity level set at 95%. For cell transfection, the siRNAs and GCDH overexpression vectors were synthesized by Ribo Bio (Guangzhou, China) and mixed with an RNAi Max reagent (Invitrogen, USA) in accordance with manufacturer’s protocol.

2.2. In vivo Mouse Model

Female BALB/c athymic nude mice that aged 5-6 weeks old were obtained from Vital River Laboratory (Beijing, China). These mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment with a consistent temperature of 25°C and a stable humidity level. They had unlimited access to water and food and were subjected to a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All procedures involving these animals were reviewed and approved by the Use and Care of Animals Committee at the Affiliated Lihuili Hospital of Ningbo University, adhering to their established guidelines. For the tumor model, MDA-MB-231 cells at a concentration of 4 × 106 were resuspended in 50 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and injected subcutaneously into the mice. Once the tumors developed to an approximate volume of 100 mm3, the mice were allocated into different groups randomly, and the treatment regimen was initiated. siRNA was administered at a dosage of 20 nmol per 20 grams of body weight via tail vein injection, repeated every three days. Throughout the study, tumor dimensions and body weight of the mice were recorded at scheduled time points. The average tumor volume was determined using the formula: (length × width2) / 2. Upon completion of the experiment, the tumors were excised, and their weights were measured.

2.3. Cell Proliferation

Cell viability and proliferation were detected by using cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8, Solarbio, China) and Cell-Light EdU Apollo567 In Vitro Kit (RiboBio, China) according to manufacturer’s instruction. For CCK-8, cancer cells were placed in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h. At the time points, CCK-8 reagent was added and reacted with cells for 2 h, then absorbance values at 450 nm were measured with a microplate reader (TECAN, China). For EdU assay, cells were seeded into 96-well plates, fixed, and labeled with EdU reagent for 30 min. Cells were then penetrated and stained with Apollo567. Imaged were taken under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

2.4. Glutamine metabolism

The glutamine metabolism was assessed by measuring the levels of intracellular glutamine, ATP and α-Ketoglutaric acid (α-KG) levels. The rates of glutamine uptake and consumption, as well as the production of glutamate, were quantified using the Glutamine Assay Kit from Abnova (Catalog No. KA1627) and the Glutamate Assay Kit from Sigma (Catalog No. MAK004-1KT), respectively. Both assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ protocols.

For assessing ATP levels, cells cultured in 24-well plates were rinsed with 500 μL of PBS and lysed using 250 μL of a lysis reagent specifically designed for luciferase assays (Promega, USA). The lysed samples were briefly centrifuged at 13,000 g for 1 minute to ensure complete separation of the cellular components. The ATP present in the cells was then measured by combining 50 μL of the supernatant from the lysed samples with 50 μL of the CellTiter-Glo reagent. The mixture was incubated in the dark for 10 minutes for reaction. The resulting luminescence, which is proportional to the amount of ATP in the sample, was measured using a plate reader (TECAN, China). The α-KG content Assay kit (BC5425, Sosarbio) was used for detection of α-KG as per manufacturer’s protocols.

2.5. Western Blot Assay

For direct immunoblot analysis, cells were first lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) to extract the proteins. The protein content was then quantified with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit, a reliable method for determining the concentration of protein samples (Bio-Rad, USA). Following quantification, the proteins were denatured and separated by molecular weight through sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The resolved proteins were transferred from the gel to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was then processed for conjugation with primary antibodies and secondary antibodies. The targeted proteins were reacted with ECL reagent and visualized in an immaign system.

2.6. qPCR Assay

Total RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s specified protocol. For complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, 300 ng of RNA was utilized, employing the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo). The real-time PCR was conducted on a Real-time PCR System using SYBR Green Mixture (Thermo). The relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2-∆∆Ct method, normalizing to the expression of GAPDH gene.

2.7. ChIP-qPCR Assay

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in accordance with the EZ-ChIP kit protocol from Millipore. The cells were exposed to formaldehyde and incubated for 10 minutes to create covalent crosslinks between DNA and protein. Following this, the cell lysates were sonicated to produce chromatin fragments with an approximate size of 200 to 300 bp. The sonicated chromatin was then subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies specific for the histone modification marker H3K27cr (Millipore, USA), or normal IgG as a negative control. The DNA from the precipitated chromatin was subsequently analyzed using qPCR assay to evaluate the enrichment of GLS1 sequence associated with the proteins of interest.

2.8. Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

The GLS1 promoter region construct was amplified from genomic DNA and was cloned into pGL3-Basic. Then, HEK293T cells were transfected with GLS1 promoter constructs by Lipofectamine 2000. After culturing 48 hours, the luciferase activity was analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The results were expressed as ratio of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) and SPSS (version 19.0). The Student’s t-test was employed for comparing the means between two groups, while one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized for multiple group comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was established as the threshold for statistical significance across all data sets evaluated.

3. Results

3.1. GCDH Modulates Proliferation and Glutamine Metabolism of Breast Cancer Cells

To analyze the role of GCDH in breast cancer metabolism, we depleted GCDH using siRNA and measured cell viability and glutamine metabolism. Results from western blot assay indicated efficient depletion of GCDH under siGCDH-1, siGCDH-2, and siGCDH-3 transfection. (

Figure 1A), here, we selected siGCDH-2 for subsequent experiments. The knockdown of GCDH notably suppressed the viability of breast cancer cells (

Figure 1B) and the number of EdU-positive proliferating breast cancer cells (

Figure 1C). The glutamine level was elevated (

Figure 1D) and the levels of glutamic acid, α-KG and ATP were significantly decreased in GCDH-depleted cells (

Figure 1E-G). These data indicated that GCDH depletion suppressed the in vitro growth and metabolism of breast cancer cells.

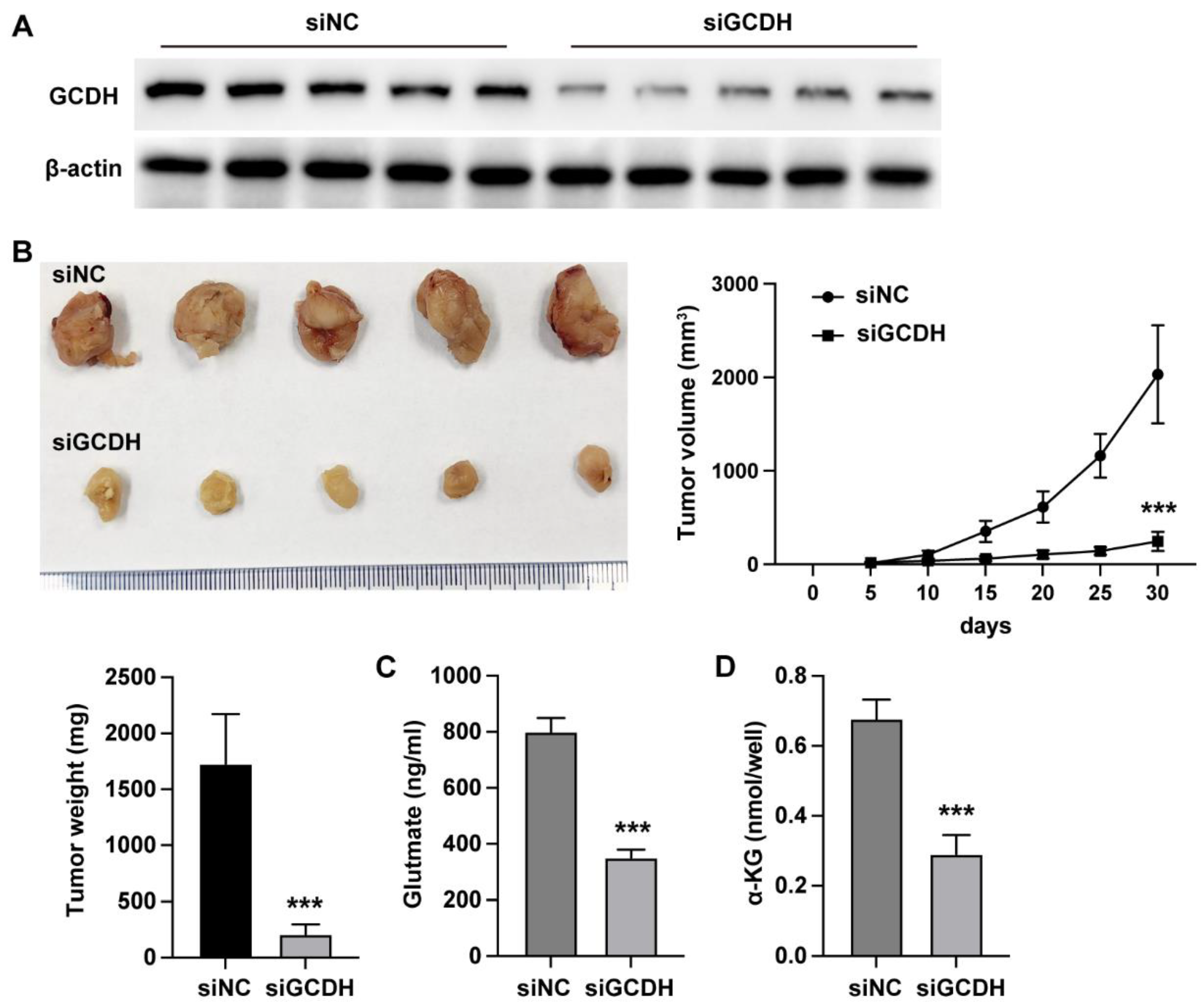

3.2. GCDH Modulates In Vivo Glutamine Metabolism of Breast Cancer

We next analyzed the in vivo effects of GCDH using xenograft mouse model. The siGCDH treatment significantly downregulated the protein level of GCDH in xenograft tumor tissues (

Figure 2A), simultaneously suppressed the in vivo growth ability of MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 2B-D). Meanwhile, the knockdown of GCDH notably elevated the glutamine level (

Figure 2E) and downregulated the α-KG level (

Figure 2F).

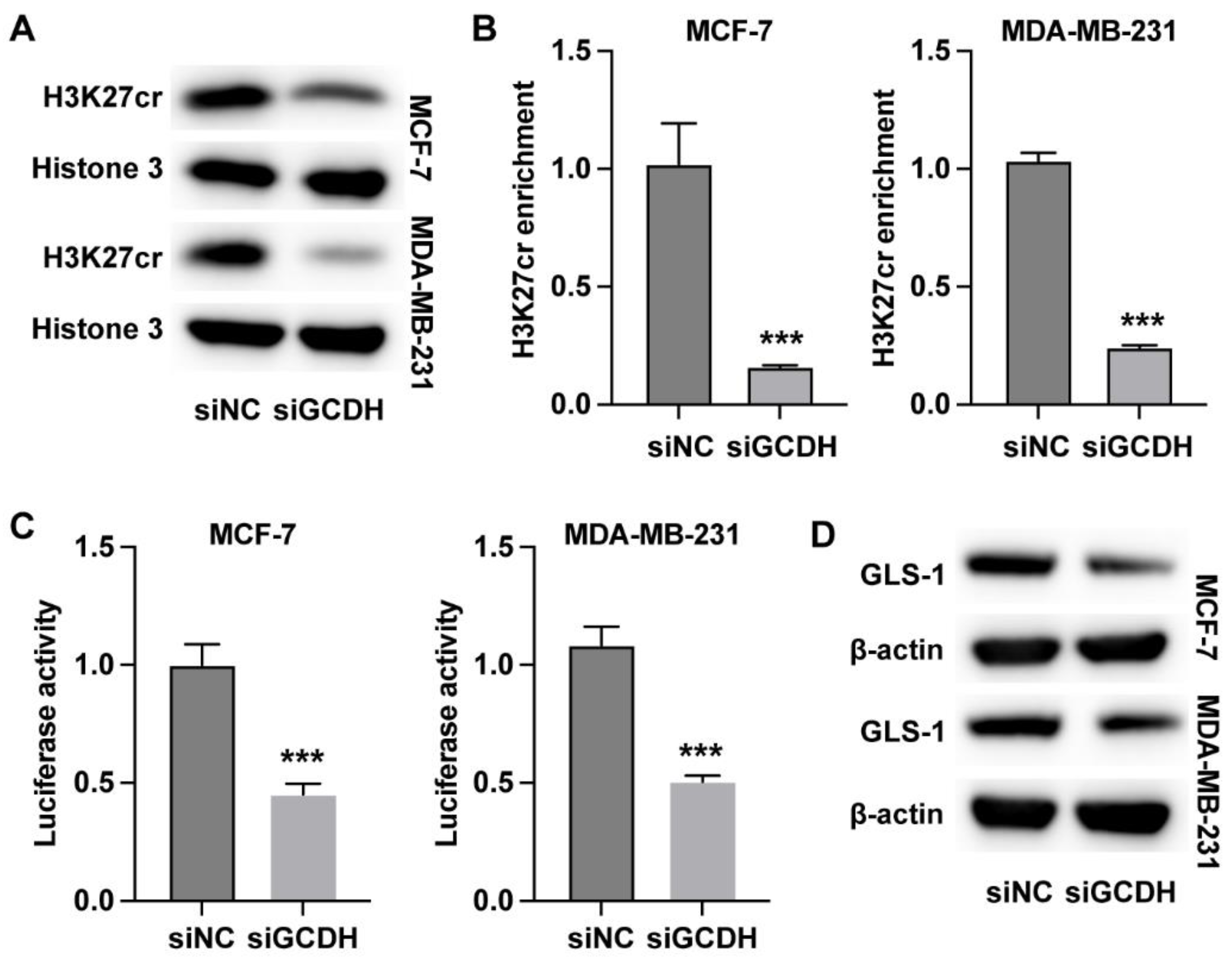

3.3. GCDH Regulates Histone Crotonylation of GLS1 in Breast Cancer Cells

Subsequently, we analyzed the regulatory mechanisms underlying the GCDH-regulated glutamine metabolism in breast cancer. We observed that knockdown of GCDH led to reduced crotonylation modification on histone H3K27 (

Figure 3A). The results from qPCR and western blot indicated that knockdown of GCDH downregulated the RNA and protein level of GLS1 (

Figure 3B and C). The enrichment of H3K27 crotonylation on GLS1 promoter region was notably reduced under depletion of GCDH (

Figure 3D). Moreover, the promoter activity of GLS1 was significantly suppressed by siGCDH (

Figure 3E). Besides, the overexpression of GLS1 in breast cancer cells could recover the protein expression of GLS1 that suppressed by siGCDH (

Figure 3F). These data indicated that GCDH epigenetically regulated the expression of GLS1 in breast cancer cells.

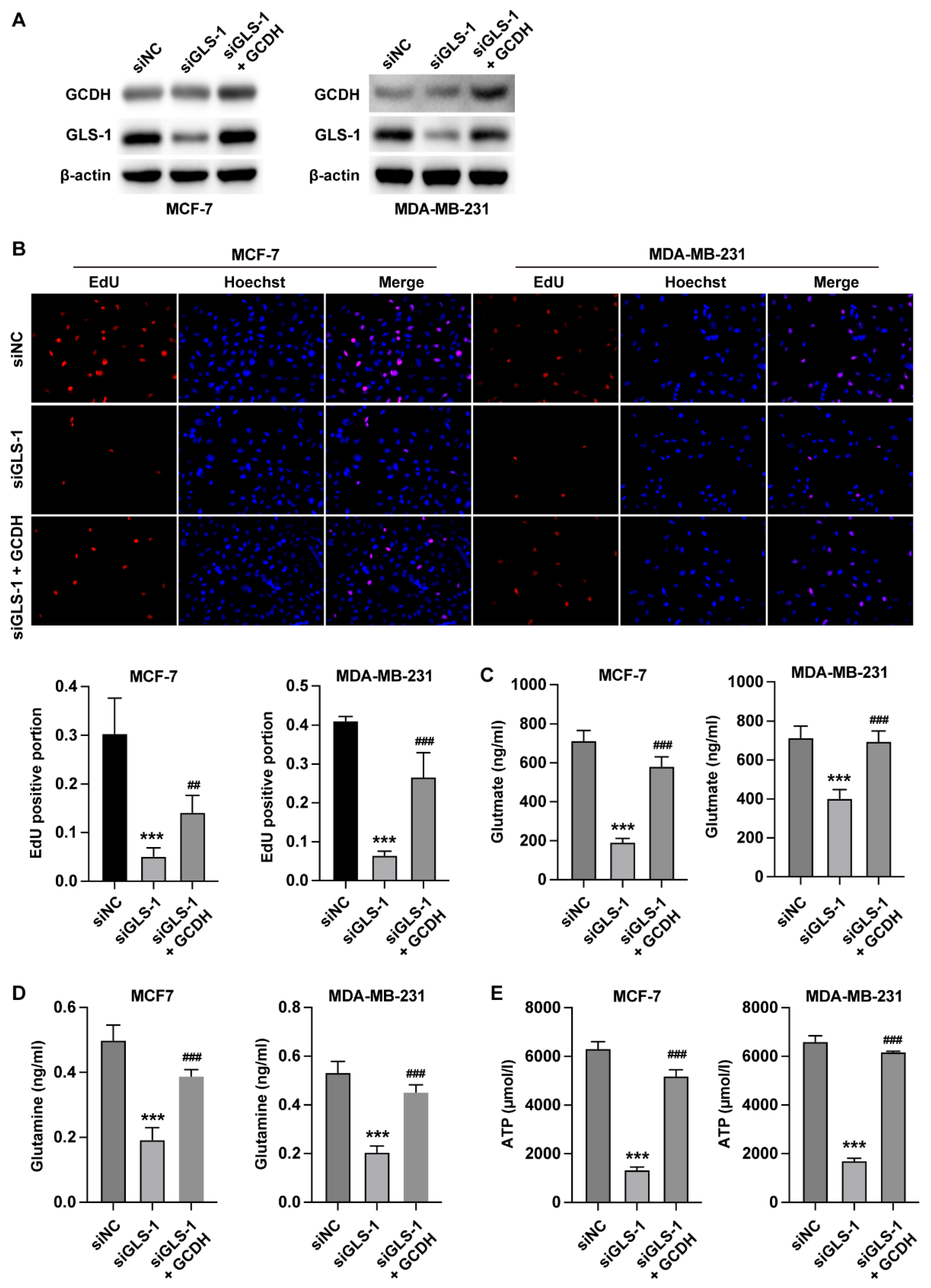

3.4. GCDH Modulates Breast Cancer Glutamine Metabolism via Targeting GLS1

Next, we verified the effects of GCDH/GLS1 axis on proliferation and metabolism of breast cancer cells. The results from EdU assay indicated that knockdown of GLS1 reduced the number of EdU-positive cells, whereas overexpression of GCDH recovered cell proliferation (

Figure 4A). Moreover, the rustles from metabolism examination revealed that knockdown of GLS1 elevated the level of intracellular glutamine (

Figure 4B) and reduced the production ofα-KG and ATP (

Figure 4C and D), whereas overexpression of GCDH abolished these effects.

4. Discussion

In current study, we performed in vitro and in vivo experiments to analyze the functions of GCDH during breast cancer development. We observed that GCDH knockdown in breast cancer cells led to suppressed cell proliferation and reduced glutamine metabolism, manifested as enhanced glutamine accumulation and reduced synthesis of glutamate acid, ATP and α-KG.

Glutamine metabolism is extensively recognized as a key factor in breast cancer progression, supplying vital nitrogen and carbon sources necessary for macromolecule biosynthesis and energy production [

10,

26]. Breast cancer cells show an increased reliance on glutamine transporters such as SLC1A5, SLC6A14, SLC7A5, and SLC7A11 for growth and proliferation [

27,

28]. These transporters enable glutamine uptake, which is then converted to glutamate by GLS, the first and rate-limiting step in glutaminolysis [

29,

30]. The subsequent conversion of glutamate to α-KG by enzymes like GLUD1 and GOT2 replenishes the TCA cycle, supporting oxidative phosphorylation and providing precursors for nucleotide and lipid synthesis [

31,

32]. In our study, we found that GCDH knockdown did not affect intracellular glutamine levels, but it did suppress the synthesis of glutamic acid, α-KG, and ATP, suggesting that GCDH operates by inhibiting glutaminolysis rather than regulating glutamine transport. Further investigation revealed that GCDH knockdown significantly reduced the expression of GLS1.

Subsequently, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the GCDH-regulated GLS1. Histone crotonylation is a non-acetyl lysine modification that occurs as frequently as acetylation, but its physiological roles remain largely unexplored. Recent studies have begun to uncover its significance in development and disease [

33,

34]. For instance, key enzymes that produce crotonyl-coenzyme A (CoA) have been found to be selectively activated in endodermal cells during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) in vitro and in mouse embryos. These enzymes enhance histone crotonylation, leading to increased expression of endodermal genes, thereby playing a vital role in endoderm differentiation [

24]. An earlier investigation showed that the coactivator p300 has the capacity to perform crotonyl transferase and acetyltransferase reactions. The study revealed that the transcriptional activation mediated by p300 through histone crotonylation is more potent compared to that achieved by histone acetylation [

35]. In our current study, we unveiled that GCDH could mediate the histone crotonylation of GLS1 and consequently activated its promoter activity and expression. The knockdown of GLS1 could repress the glutamine metabolism, while overexpression of GCDH could abolish these effects. These findings established the role of GLS1 as mediator for GCDH-regulated glutamine metabolism.

5. Conclusion

To summarize, we identified GCDH as a regulator for breast cancer development and revealed that GCDH modulated the glutamine metabolism. Mechanistic studies further demonstrated that GCDH epigenetically modulated the histone crotonylation and expression of GLS1. Our findings provided new molecular mechanisms underlying breast cancer development and presented a novel target for cancer treatment.

Funding

Medical and Health Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2024KY1482).

References

- B. Faubert, A. B. Faubert, A. Solmonson, R.J. DeBerardinis, Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression, Science, 368 (2020).

- Xia, L.; Oyang, L.; Lin, J.; Tan, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, N.; Yi, P.; Tang, L.; Pan, Q.; Rao, S.; et al. The cancer metabolic reprogramming and immune response. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanavat, M.; Shahrouzian, M.; Zayeri, Z.D.; Banihashemi, S.; Kazemi, S.M.; Saki, N. Digging deeper through glucose metabolism and its regulators in cancer and metastasis. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, N. Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: can it be exploited for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Shi, H.; He, R.; Chen, C.; Zhou, W. Glucose metabolism and tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer: A key link in cancer progression. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1038650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, A.F.; Mahmoud, W.; Al-Harizy, R.M. Targeting glucose metabolism to suppress cancer progression: prospective of anti-glycolytic cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 150, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.L. Lieu, T. E.L. Lieu, T. Nguyen, S. Rhyne, J. Kim, Amino acids in cancer, Experimental & molecular medicine, 52 (2020) 15-30.

- Sivanand, S.; Heiden, M.G.V. Emerging Roles for Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, C.T.; Wasti, A.T.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Glutamine and cancer: cell biology, physiology, and clinical opportunities. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3678–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Byun, J.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, K.-G. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, B.J.; Stine, Z.E.; Dang, C.V. From Krebs to clinic: Glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluntun, A.A.; Lukey, M.J.; Cerione, R.A.; Locasale, J.W. Glutamine Metabolism in Cancer: Understanding the Heterogeneity. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-H.; Qiu, Y.; Stamatatos, O.; Janowitz, T.; Lukey, M.J. Enhancing the Efficacy of Glutamine Metabolism Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B. Salovska, Y. B. Salovska, Y. Liu, Post-translational modification and phenotype, Proteomics, 23 (2023) e2200535.

- Millán-Zambrano, G.; Burton, A.; Bannister, A.J.; Schneider, R. Histone post-translational modifications — cause and consequence of genome function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Luo, H.; Lee, S.; Jin, F.; Yang, J.S.; Montellier, E.; Buchou, T.; Cheng, Z.; Rousseaux, S.; Rajagopal, N.; et al. Identification of 67 Histone Marks and Histone Lysine Crotonylation as a New Type of Histone Modification. Cell 2011, 146, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickner, J.H. Inheritance of epigenetic transcriptional memory through read–write replication of a histone modification. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2023, 1526, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrés, M.; García-Gomis, D.; Ponte, I.; Suau, P.; Roque, A. Histone H1 Post-Translational Modifications: Update and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, N.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Q.; Cong, X. Lactylation: the novel histone modification influence on gene expression, protein function, and disease. Clin. Epigenetics 2024, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyghton, M.P.; Cheng, A.W.; Welstead, G.G.; Kooistra, T.; Carey, B.W.; Steine, E.J.; Hanna, J.; Lodato, M.A.; Frampton, G.M.; Sharp, P.A.; et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21931–21936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Gao, P. Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer. Protein Cell 2022, 13, 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Konuma, T.; Sharma, R.; Wang, D.; Zhao, N.; Cao, L.; Ju, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Bosch, A.; et al. Histone H3 lysine 27 crotonylation mediates gene transcriptional repression in chromatin. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2206–2221.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Z. Histone crotonylation-centric gene regulation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2021, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xu, X.; Ding, J.; Yang, L.; Doan, M.T.; Karmaus, P.W.; Snyder, N.W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.-L.; Li, X. Histone crotonylation promotes mesoendodermal commitment of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 748–763.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, Y.; Cui, X.; Xu, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, L.; Li, B.; Lu, Y.; Guan, Q.; et al. Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase suppresses tumor progression and shapes an anti-tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.C.; Yu, Y.C.; Sung, Y.; Han, J.M. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.J.; Kim, E.-S.; Koo, J.S. Amino Acid Transporters and Glutamine Metabolism in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zeng, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, C.; Li, Y.; Tu, J.; Nephew, K.P.; Long, X. Glutamine metabolism in breast cancer and possible therapeutic targets. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 210, 115464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johmura, Y.; Yamanaka, T.; Omori, S.; Wang, T.-W.; Sugiura, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kumamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; et al. Senolysis by glutaminolysis inhibition ameliorates various age-associated disorders. Science 2021, 371, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Venneti, S.; Nagrath, D. Glutaminolysis: A Hallmark of Cancer Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Quadri, N.; Ramasamy, R.; Jiang, X. Glutaminolysis and Transferrin Regulate Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Cao, G.; Sun, G.; Zhu, L.; Tian, Y.; Song, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, W.; et al. GLS1-mediated glutaminolysis unbridled by MALT1 protease promotes psoriasis pathogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5180–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Martín-Sánchez, D.; Sánchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Sanz, A.B.; Ortiz, A. The Contribution of Histone Crotonylation to Tissue Health and Disease: Focus on Kidney Health. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Cao, X.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Tian, S.; Gong, T.; Xiong, H.; Cao, P.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; et al. Nuclear Condensation of CDYL Links Histone Crotonylation and Cystogenesis in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 33, 1708–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabari, B.R.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Yong-Gonzalez, V.; Molina, H.; Kong, H.E.; Dai, L.; Shimada, M.; Cross, J.R.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Intracellular Crotonyl-CoA Stimulates Transcription through p300-Catalyzed Histone Crotonylation. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).