1. Introduction

Whilst the placental cord insertion can be efficiently evaluated with two-dimensional and colour doppler ultrasound imaging [

1,

2], ultrasound assessment of the placental cord insertion (PCI) site can be complex, particularly when the cord insertion is abnormal, and requires proficient sonographer spatial perception. Despite the availability of excellent 2D resources, visualising anatomical spatial relationships remains challenging [

3]. The production of 3D printed models can bypass this problem by providing clear visualisation of spatial relationships [

4].

3D printing is a rapidly developing technology showing great potential in medical applications; in particular, it has been shown that 3DPMs offer exceptional dimensional awareness [

5]. 3D anatomical models are now widely used in many aspects of medicine [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] including education [

11,

12,

13], pre-surgical planning [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and patient communication [

19,

20,

21] due to advancements in 3D printing technology, reduction in costs and ease of access to 3D printing facilities [

6,

17]. Patient-specific or personalised 3D models can be printed at 1:1 scale based on imaging datasets, mainly computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound [

14]. Further, these models can be printed with different materials depending on the usefulness for clinical applications [

19,

22]

Current literature describes the production of a variety of 3DPMs for a diverse array of medical applications with superior advantages reported when compared to the use of standard two-dimensional (2D) or 3D image visualisations [

6,

20,

23]. In the field of obstetrics, raw data obtained from 3D ultrasound imaging is being used to create 3DPMs to facilitate antenatal assessment, maternal and paternal fetal attachment and presurgical planning of fetal malformations [

24,

25]. To the best of our knowledge no studies have described the creation of 3DPMs that depict the PCI. This study aimed to address this research gap by assessing the potential value of 3DPMs of the PCI in ultrasound education. Our 3DPMs are patient specific, based on images of selected patient’s cases, thus the models reflect realistic physiological and pathological processes. We hypothesized that our 3DPMs would serve as a useful adjunct for clinical education in ultrasound imaging of the PCI site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. 3D Model Development

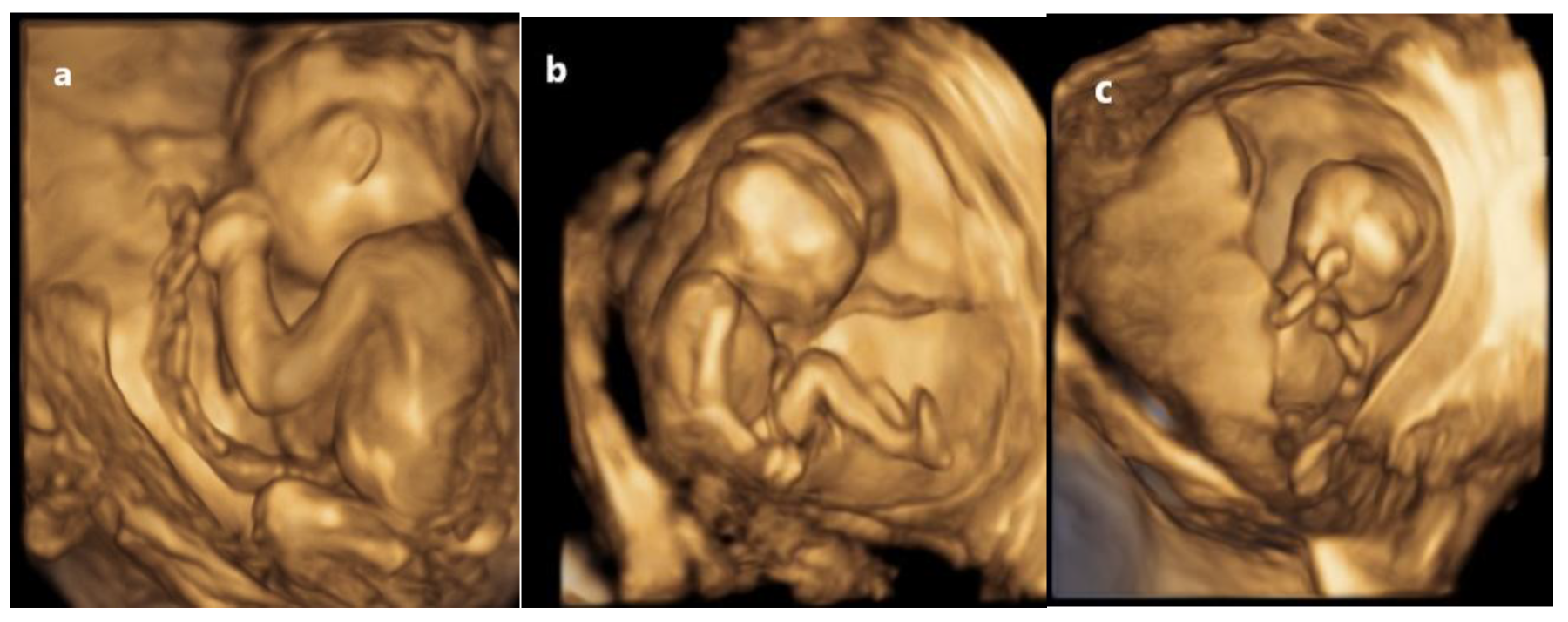

Three 3D model representing normal, marginal and velamentous placental cord insertions were developed using raw ultrasound data of selected three patients at Vestrum Ultrasound for Women (VUW) who provided informed consent. We acquired 3D static images of the normal PCI, MCI and VCI (the gestational ages of the fetuses were 20 weeks 3 days, 16 weeks 2 days and 12 weeks 4 days gestation, respectively) using a GE Voluson E10 ultrasound machine (GE Healthcare, Solingen, Germany) at VUW (

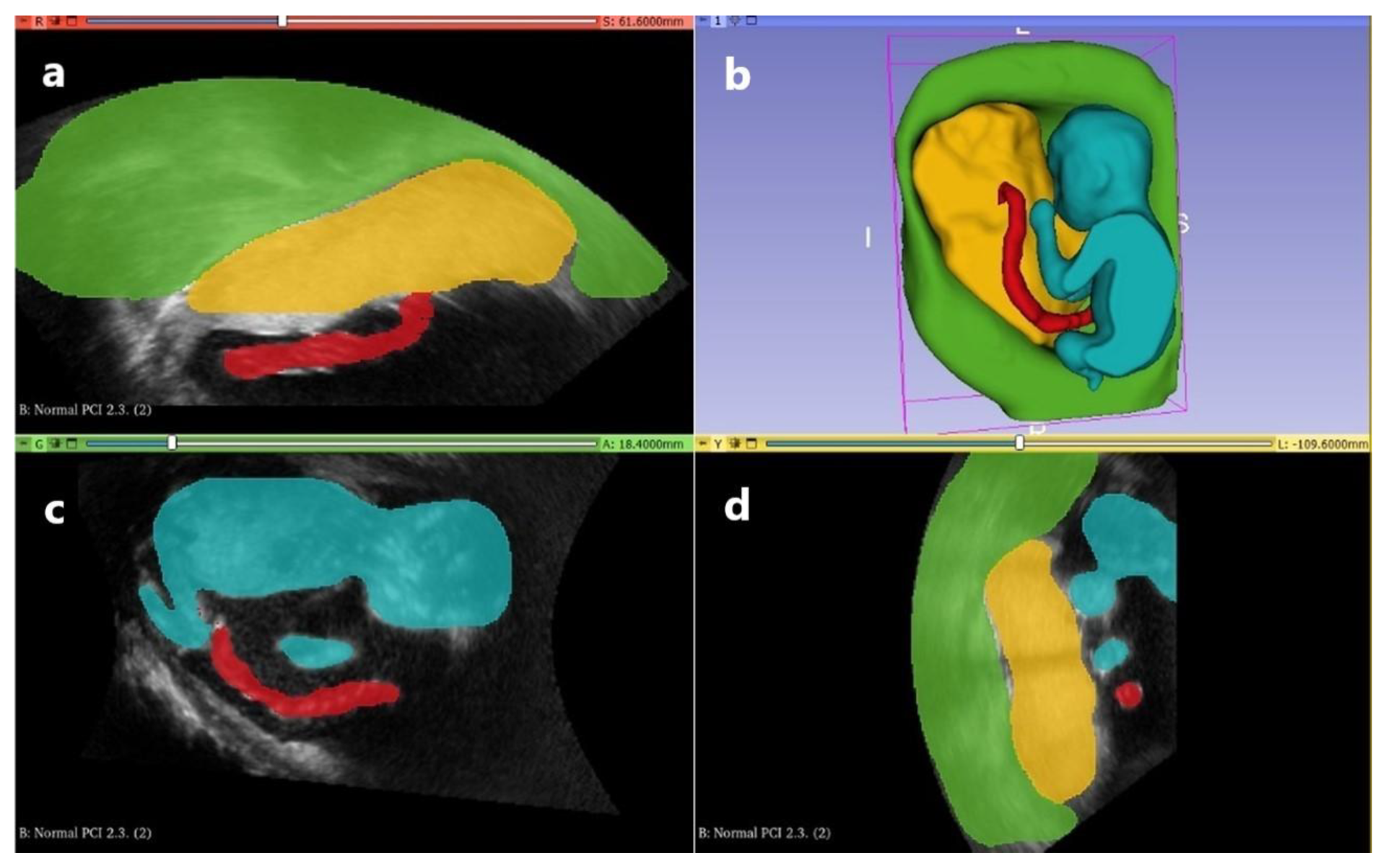

Figure 1). These images in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format were imported into an open source software 3D Slicer (

www.slicer.org) version 5.4.0. Segmentation of the images for each PCI was performed manually to accurately delineate the boundaries of the uterus, placenta, fetus and umbilical cord with

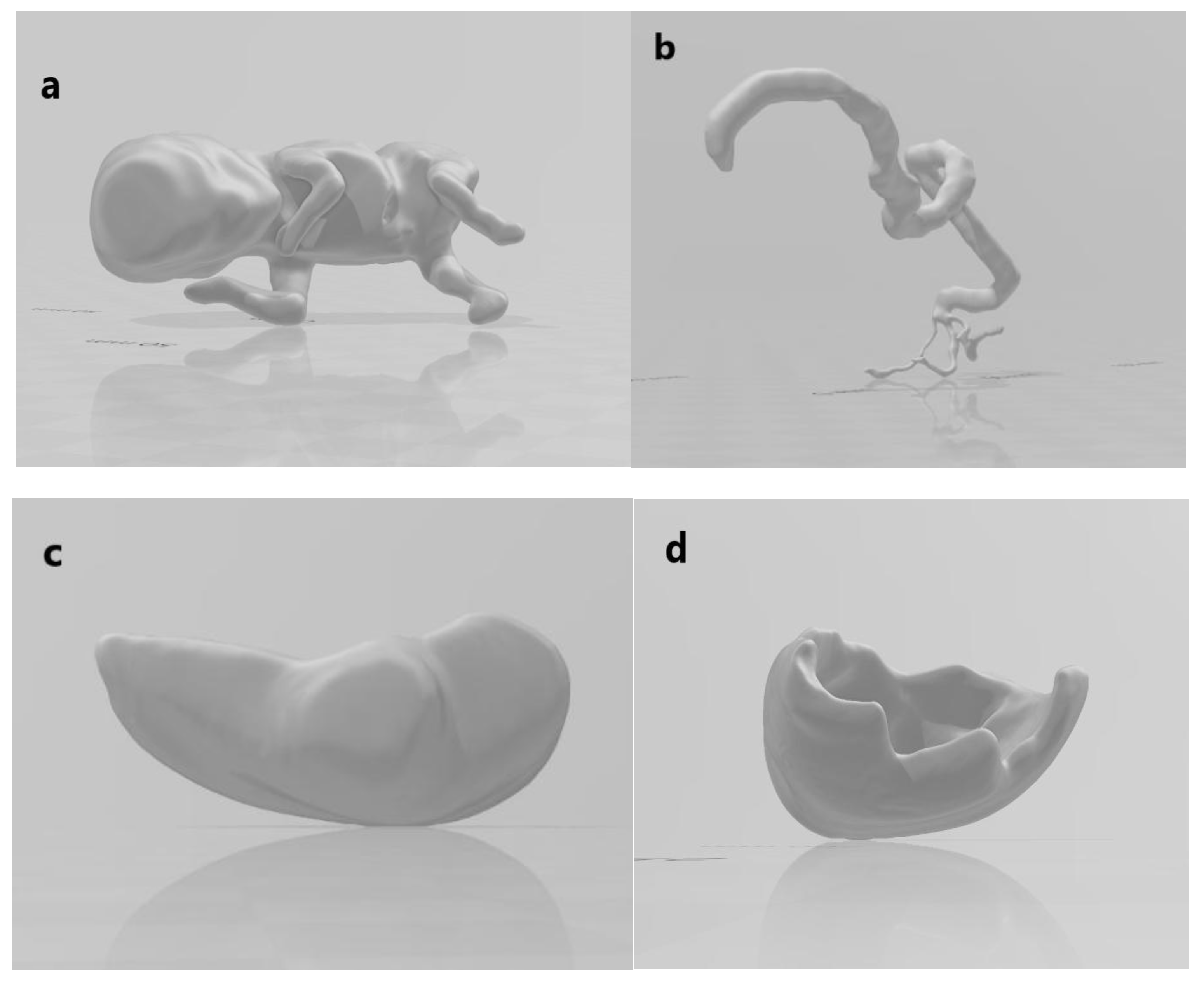

Figure 2 illustrating the segment editor for the NCI. The segmented volume data were converted to Standard Tessellation Language (STL) files.

Figure 3 demonstrates the STL files for the VCI model.

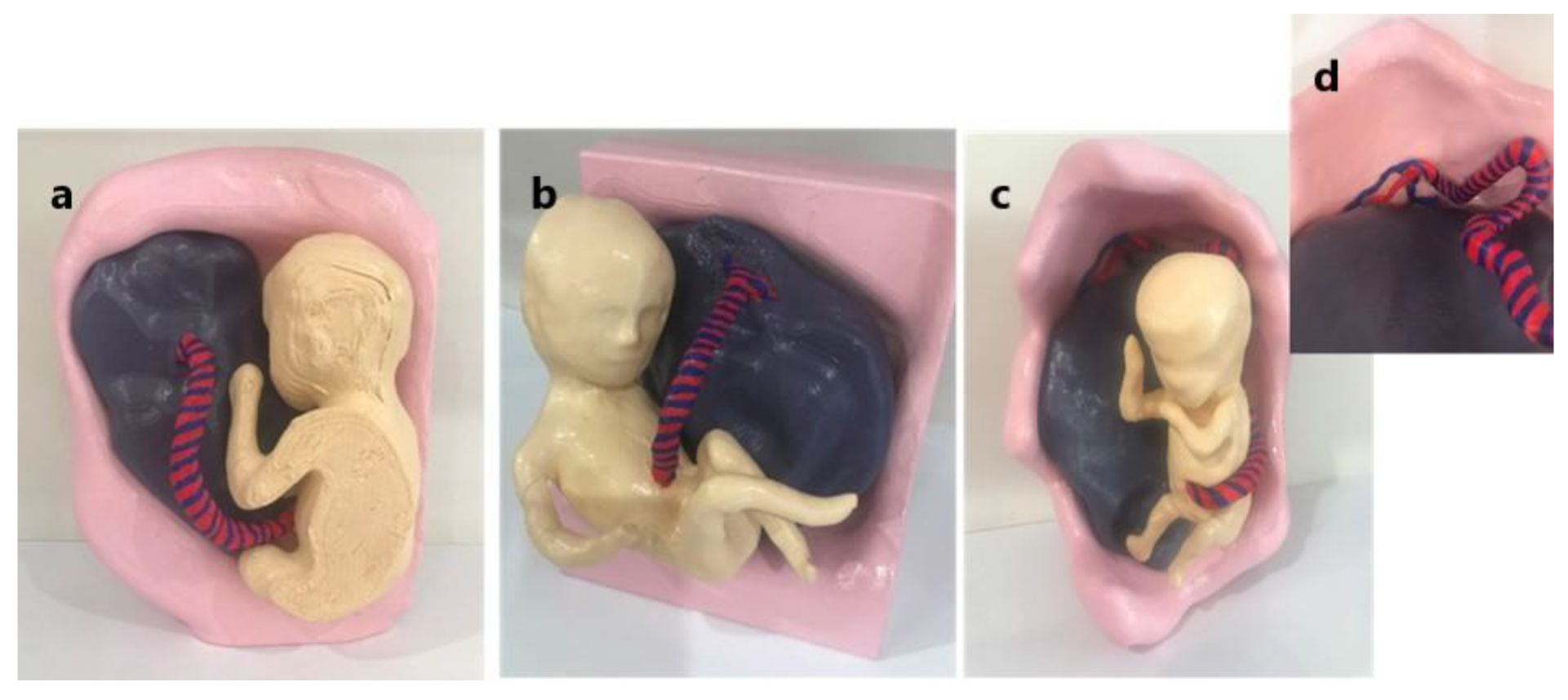

The 3DPMs were printed using a Raised 3D N2 Plus fused deposition modelling printer and utilising polylactic acid material. Each of the three models comprised four STL files (fetus, umbilical cord, placenta and uterus) which were printed in a ratio of 1:1 for the NCI and MCI models and a ratio of 1:2 for the VCI model due to the earlier gestation of the fetus. The individual components of the models were glued together and painted schematically resulting in 3DPMs demonstrating the anatomical relationship of the placenta, cord and fetus.

Figure 4 illustrates the 3DPM construction process and

Figure 5 demonstrates the three completed 3DPMs.

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

Thirty-three sonographers were recruited from a large private medical imaging practice in Western Australia through convenience sampling. Each participant attended a face-to-face demonstration of normal, marginal and velamentous cord insertions utilizing 2D ultrasound images, ultrasound videos and our 3DPM. The sonographers were initially asked to complete a questionnaire (Supplementary file 1) establishing:

1. Consent;

2. Demographics (years of experience as a sonographer);

3. Confidence in assessing the PCI with ultrasound and ability to spatially visualize the placenta and PCI utilizing five level Likert scale rating (with 1 indicating extremely poor, 5 indicating excellent).

Ultrasound images and videos of the three classifications of cord insertion were then presented in the form of a power point presentation (Supplementary file 2) followed by a hands-on demonstration of the 3DPM. Participants were then asked to complete a subsequent questionnaire (Supplementary file 3). A one to three ranking scale was utilized to establish which of the three methods of demonstrating the PCI (2D ultrasound images, 2D ultrasound videos and 3DPM), if any, best enhanced the participants’ ability to spatially visualize the relationship between the placenta and the PCI. Five level Likert scale questions (with 1 indicating not at all, 5 indicating very much) were used to determine if the 3DPMs:

1. Increased confidence in identifying NCI, MCI and VCI with ultrasound;

2. Improved understanding of the structural relationship between the placenta and the PCI;

3. Enhanced ability to spatially visualize the placenta and the PCI.

Participants opinions on the usefulness of the 3DPMs in ultrasound education and their likelihood of recommending the 3DPMs as an educational device were ascertained using five level Likert scale questions (with 1 indicating not useful/not likely, 5 indicating extremely useful/likely).

Participants were given the option of providing additional comments at the end of the second questionnaire. The demonstration, inclusive of questionnaire completion, took approximately 15 minutes for each participant to complete.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Excel v2209 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA) and G*Power v3.1.9.7 (Heinrich-Heine-Universit€ at, D€usseldorf, Germany) [

26]. Post hoc analysis using one-way ANOVA in G*Power with the effect size of 0.61, level of significance 5% and sample size of 33, calculated the power of our study to be 86%. The Shapiro-Wilk test demonstrated the ordinal data for the Likert scale questions was not normally distributed (P < 0.05). Cronbach’s alpha tested for internal consistency of the Likert scale questions with α = 0.977 for the pre-demonstration survey and α = 0.938 for the post- demonstration survey, indicating high internal consistency and thus reliability of the survey questions. Additionally, individual questions were deemed reliable as removal of the questions independently from the analysis resulted in Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.97 to 0.978 (pre-demonstration) and 0.928 to 0.941 (post-demonstration). Descriptive statistics measured the mean and standard deviation of Likert and rating scale questions. While there is controversy in the literature as to whether parametric tests can be used to analyse non-normally distributed ordinal data, Dr Geoff Norman has shown “compelling evidence, with actual examples using real and simulated data, that parametric tests not only can be used with ordinal data, such as data from Likert scales, but also that parametric tests are generally more robust than nonparametric tests”[

27] (p. 542). Hence, although data was not normally distributed, parametric one-way ANOVA test was conducted to establish association between the participants’ years of experience and their questionnaire responses. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Qualitative data from the free-text section of the questionnaire was analysed thematically, with data categorised into five themes.

2.4. Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021-0629), SKG Radiology clinical standards committee and VUW.

3. Results

A total of 33 sonographers were recruited in this study. The participants’ years of experience were categorized into three groups with Group 1 having ≤ 3 years’ experience (n=12), Group 2 having 4 to 10 years’ experience (n=9) and Group 3 having more than 10 years’ experience (n=12).

Results indicate participants’ confidence in assessing the PCI and ability to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI for all PCI classifications, pre-demonstration, was higher than average with mean ratings documented in

Table 1. It is noted that the mean rating for both confidence and spatial awareness decreased with increasing PCI complexity.

We further analysed the data to establish if there is any relationship between a participant’s years of experience and their responses. There is a significant association between a sonographer’s experience level and (i) their confidence in assessing the PCI and (ii) their ability to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI, with those sonographers in group one (least experienced participants) being less confident and less able to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI than those in groups 2 (p-values < 0.05 for all PCI types). There is no significant association when comparing groups 2 and 3 (Supplementary Table 1).

Following the demonstration, participants were asked to rank the 2D ultrasound images, 2D ultrasound videos and 3DPMs from 1 to 3 (with 1 being least helpful and 3 being most helpful) to determine which method of PCI demonstration was the most effective in terms of spatially visualising the PCI. Results showed most participants found the ultrasound images to be the least useful method for spatially visualising the NCI, MCI and VCI (ranked 1 in 81.8%, 78.8% and 84.8%, respectively), and the 3DPMs the most beneficial (ranked 3 in 69.7%, 75.8% and 78.8%, respectively).

Table 2 documents the ranking of the images, videos and 3DPMs for each PCI category. There is no significant association between the ranking and participant’s years of experience.

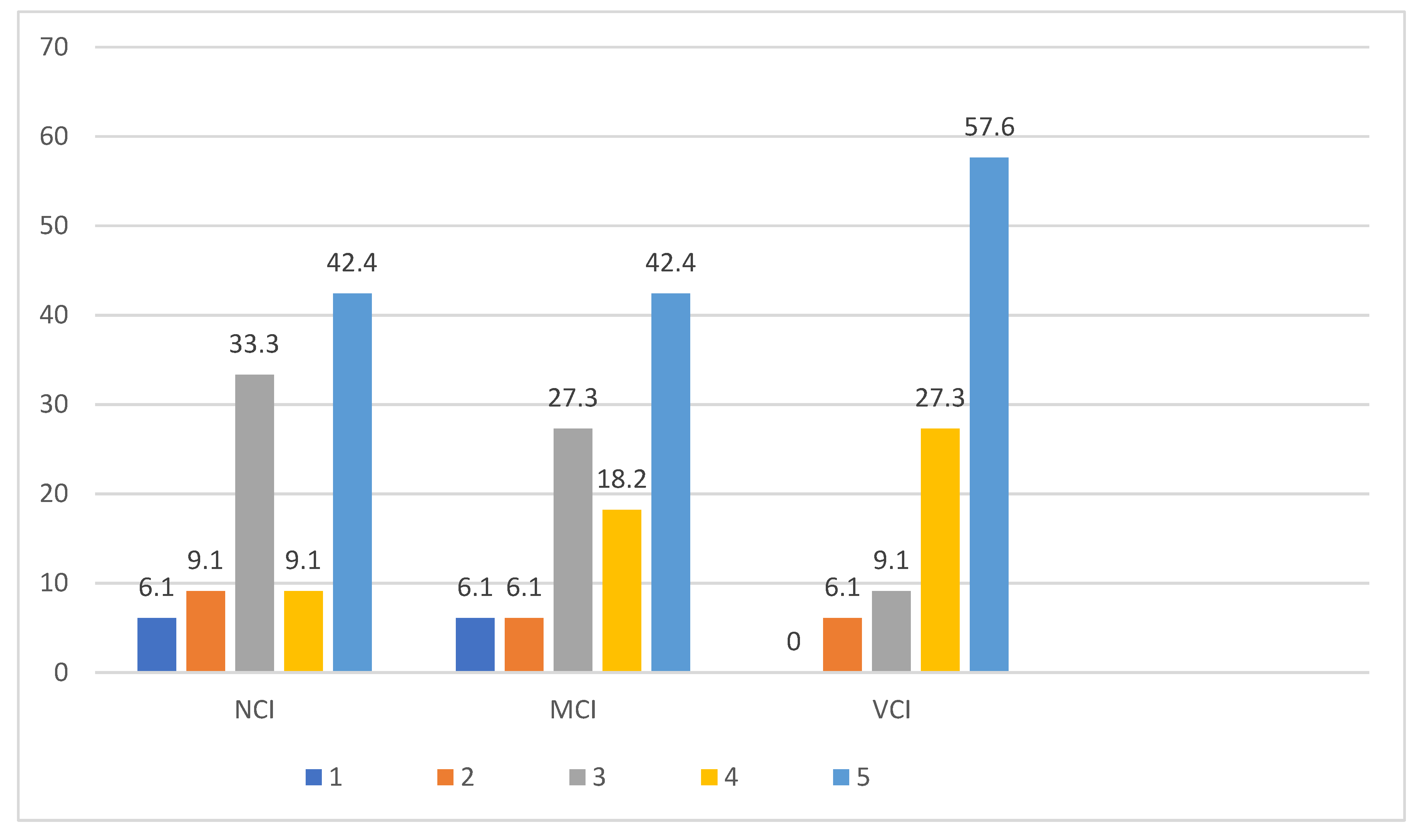

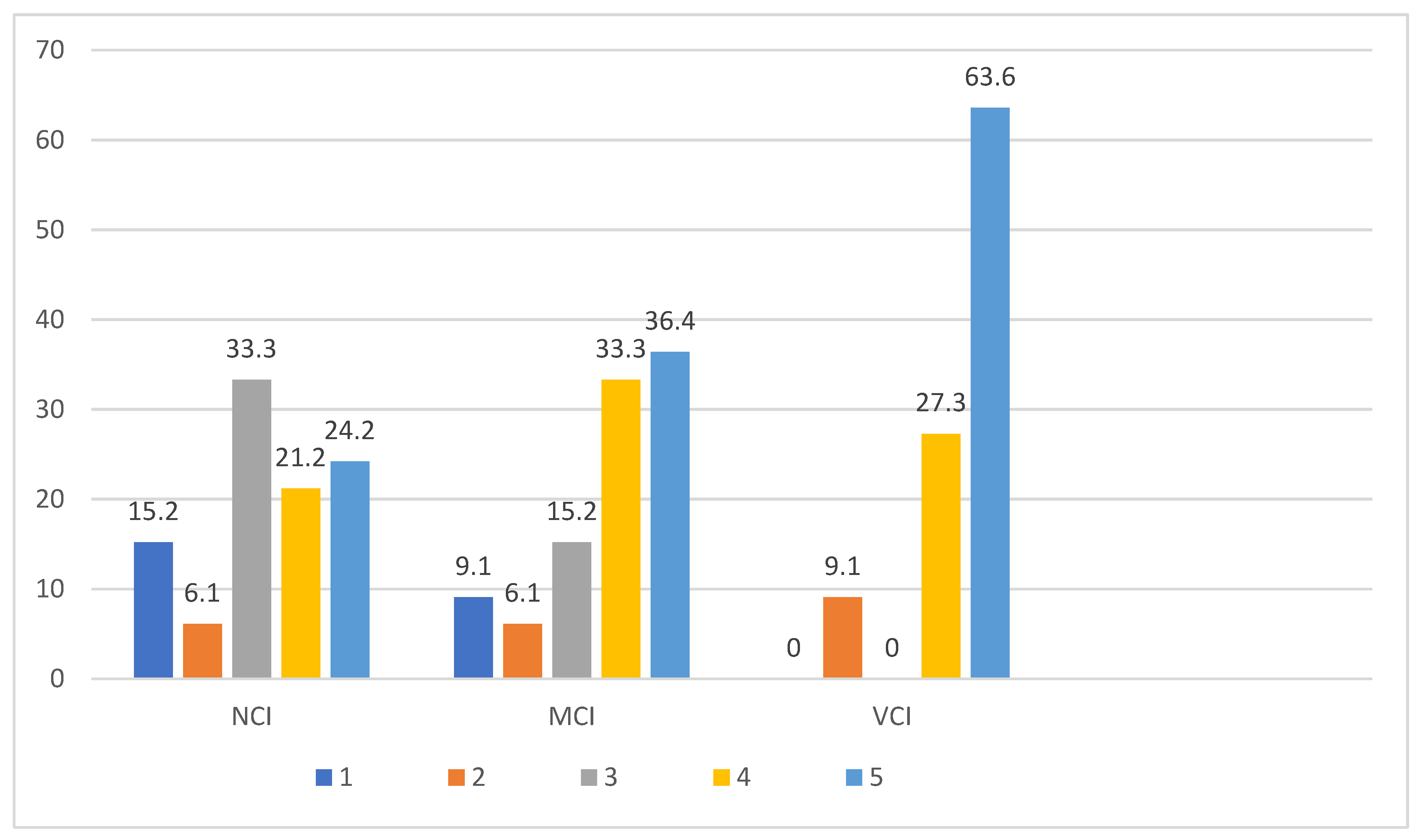

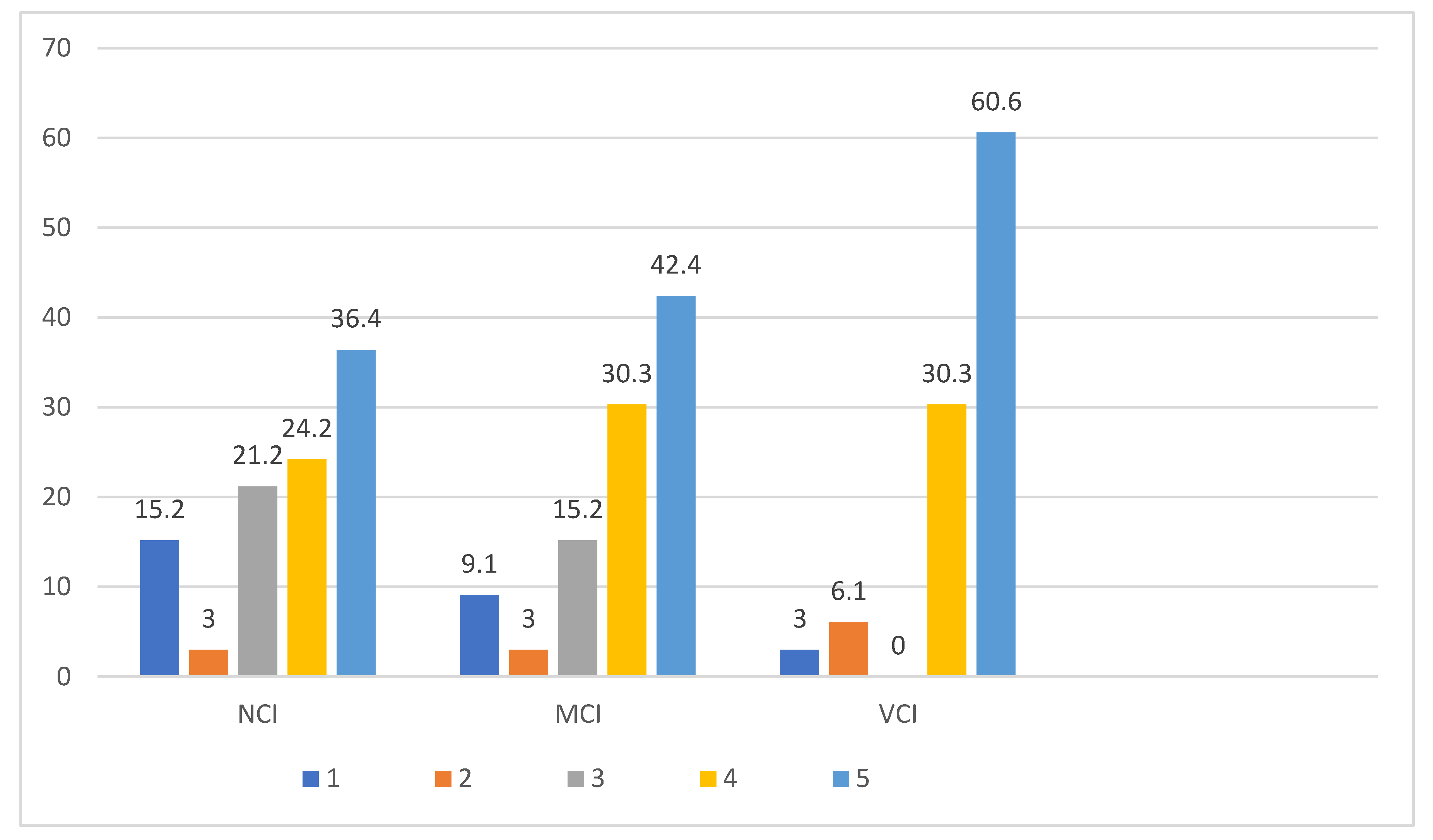

The 3DPMs rated highly for each question with sonographer confidence, understanding and ability to spatially visualise the PCI increasing in proportion to PCI complexity as illustrated in

Table 3 and

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

There is no significant association between a sonographer’s years of experience and the 3DPMs improving their confidence, understanding or ability to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI (

Table 4) and no significant associations were determined when comparing the grouped years of experience (Supplementary Table 2).

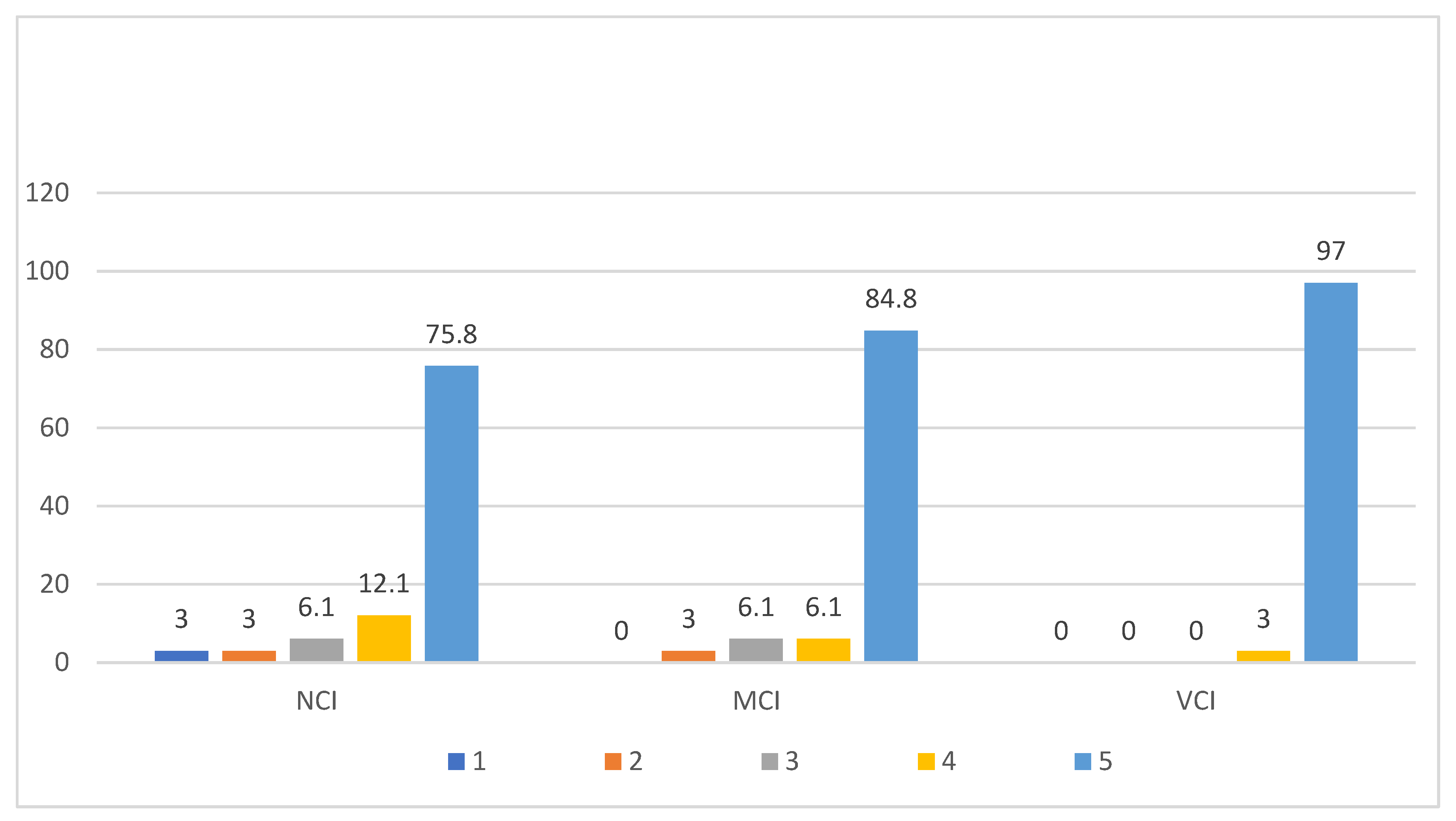

Most sonographers indicated they felt the models of each PCI type would be useful in ultrasound education (

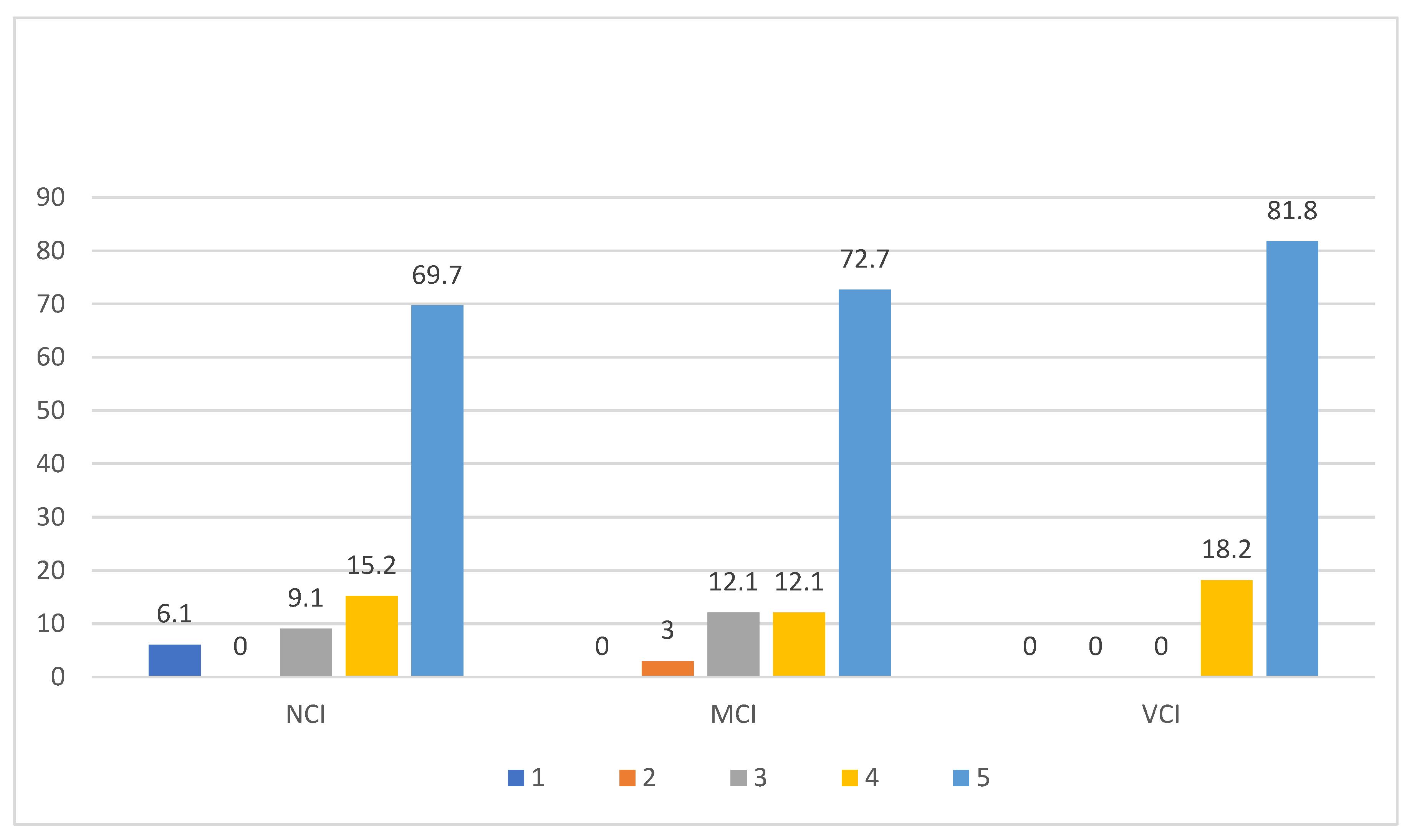

Figure 9) with 75.8%, 84.8% and 97% indicating the models of normal, marginal and velamentous cord insertions respectively, would be extremely useful. Participants were also asked how likely they would be to recommend the models as an educational device with 69.7%, 72.7% and 81.8% indicating they would recommend normal, marginal and velamentous cord insertion models respectively (

Figure 10).

Table 5 presents the participants’ mean ratings for the usefulness of the 3DPMs in ultrasound education. There is no significant association between these opinions and the participants’ years of experience (

Table 6), and no significant associations were determined when comparing the grouped years of experience (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 5.

Mean ratings of usefulness of 3DPMs in ultrasound education based on participants’ opinions.

Table 5.

Mean ratings of usefulness of 3DPMs in ultrasound education based on participants’ opinions.

| Opinions |

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

SD |

| Do you think the 3D model of the NCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.55 |

0.97 |

| Do you think the 3D model of the MCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.73 |

0.72 |

| Do you think the 3D model of the VCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.97 |

0.17 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the NCI as an educational device? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.42 |

1.09 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the MCI as an educational device? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.54 |

0.83 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the VCI as an educational device? |

33 |

1 |

5 |

4.81 |

0.39 |

Table 6.

Participant opinion of 3DPMs according to years of experience, p-values.

Table 6.

Participant opinion of 3DPMs according to years of experience, p-values.

| Opinions |

p-value |

| Do you think the 3D model of the NCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

0.605 |

| Do you think the 3D model of the MCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

0.601 |

| Do you think the 3D model of the VCI would be useful in ultrasound education? |

1.000 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the NCI as an educational device? |

0.582 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the MCI as an educational device? |

0.930 |

| Would you recommend the 3D model of the VCI as an educational device? |

0.622 |

Eleven participants provided comments in the free text section of the questionnaire (

Table 7). The feedback was categorised into five themes: (i) use of 3DPMs of the PCI as educational tools; (ii) improved visualisation of the PCI; (iii) extended use of the 3D models; (iv) general comments; and (v) limitations, with several sonographers providing comments applicable to multiple themes.

4. Discussion

Comprehensive understanding of complex anatomy can be challenging in all aspects of medical imaging. Imaging modalities primarily produce two-dimensional images which limits spatial perception of anatomical relationships [

28]. Studies have demonstrated medical students find visualising anatomy in three dimensions particularly challenging [

29]. Even when 3D imaging is undertaken, interpreting 3D images on flat 2D screens can impede understanding of complicated anatomy [

28,

30,

31]. The production of 3D printed models can bypass this problem by providing clear visualisation of spatial relationships [

4].

This study was designed to assess the effectiveness of 3D printed models of the PCI in ultrasound education. Participants in our study initially indicated a higher than average rating of confidence in assessing the PCI and their ability to spatially visualise the PCI with ratings decreasing with increasing complexity of the PCI. We observed a significant association between these results and a participant’s years of experience with those sonographers with less experience expressing the lowest confidence and least aptitude for spatial orientation. Following the demonstration, participants indicated the 3D models improved their confidence in assessing the PCI as well as their understanding of the placenta/PCI relationship and their spatial visualisation of the PCI. The 3D model of the VCI rated the highest out of the three models, indicating the benefit of the 3D models increases with PCI complexity. Participants’ responses following the demonstration showed no significant relationship between their feedback and their years of experience suggesting the 3D models are useful for sonographers with all levels of clinical experience.

Backhouse et al express that despite the availability of excellent 2D resources, visualising anatomical spatial relationships remains challenging [

3]. This suggests 2D resources on their own may not be adequate for teaching anatomy, one of the most onerous subjects for students due to the need for spatial visualization [

32]. Halpern et al propose the use of 3D models would improve a student’s understanding of a 2D ultrasound image resulting in increased confidence in recognizing anatomy [

33]. In our study, participants were asked to rank the 2D ultrasound images, 2D ultrasound videos and 3D printed models according to which was most effective for spatial visualisation of the PCI with results indicating sonographers found the 2D ultrasound images least helpful and the 3D models the most beneficial for all PCI types. Our findings concur with the literature that 3D printed models increase spatial visual orientation [

34] and assist with understanding anatomical relationships [

35].

3D printed models are being progressively valued in ultrasound education with their ability to accurately depict anatomical structures [

16,

36] and provide both a visual and tactile representation which improves understanding, particularly of complex anatomy [

6,

18]. A 3D model can be physically handled and rotated providing considerable advantage over 2D and 3D imaging [

6,

18]. Most participants in our study indicated the 3D PCI models would be beneficial in ultrasound education. Backhouse et al investigated the effect a 3D printed model of orbit had on optometry students’ education. The response of their participants was extremely positive with the students indicating the model enhanced their ability to spatially visualise anatomical relationships preferring the 3D models over traditional resources [

3].

In their literature review, Halpern et al found 14 of 16 studies included in their review demonstrated 3D modelling applications enhanced student education in ultrasound [

33]. Tan et al have shown 3D models enhance the understanding of and contribute significantly to anatomical education [

34]. Interestingly, a study by Yi et al that evaluated the educational value of 3DPMs, 3D images and 2D images in assessing the ventricular system of the brain showed not only did their participants rate their 3DPMs higher than 3D images, but the models distinctly increased interest and enthusiasm among the students in their research [

37].

The free text section of our questionnaire introduced new concepts for the use of 3D models in obstetric ultrasound education with two participants suggesting 3DPMs of placental location and placental developmental variation would also be beneficial. Further future direction involves utilising the 3DPMs for enhanced patient understanding of placental and PCI anatomy and pathology.

As with all advancements in medical education, cost and feasibility must be considered when assessing the practicality of introducing 3DPMs into ultrasound education. 3D printing technology is being used increasingly in medical and educational applications with manufacture costs varying greatly. Current literature describes decreasing costs [

3,

6,

17] however expenditure is relative to the model being created and materials used. Perhaps the most significant cost is time with the printing process sometimes taking days to complete. In our study the individual components of the models ranged from 1 to 28.5 hours to print with a cost of approximately AUD

$50 per model, inclusive of materials and printing, making our models an affordable and readily accessible adjunct to ultrasound education.

We would like to acknowledge some limitations of our study. As a small cohort from a single private radiology practice in Western Australia were involved in our research our results may not be representative of other ultrasound departments. The validity of our results would benefit from a larger group of participants from a diverse range of ultrasound settings including both private and public departments offering general ultrasound examinations and/or specialised obstetric ultrasound. Our demonstration was not pilot tested thus although Cronbach’s alpha indicated reliability of the survey questions, we cannot be sure of the comprehensibility of the power point presentation and 3D model demonstration.

5. Conclusions

3D printing technology is rapidly evolving, and the benefits of printed models are being increasingly appreciated. This study has shown 3DPMs of the PCI could be beneficial in ultrasound education. Participants indicated improved confidence in assessing the PCI and enhanced spatial orientation of the PCI, particularly when complex, following demonstration of the models. The 3DPMs were the preferred method of demonstrating the PCI over more traditional resources of 2D ultrasound images and ultrasound videos. We believe our 3DPMs could prove a valuable and low cost addition to ultrasound education with the potential to increase the accuracy of 2D ultrasound assessment of the PCI.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Attached as separate word document.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: S.W, Z.S and S.M..; writing—original and draft preparation, S.W.; project administration, Z.S and S.M..; project supervision, Z.S and S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.W, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Yin How Wong, Taylor’s University, Malaysia for facilitating the printing of the 3D PCI models. We also thank SKG Radiology for hosting the demonstrations, the sonographers who participated in this survey and Dr Andrea Liddiard, Vestrum Ultrasound for Women, for her clinical assistance with image data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allaf, M.B.; Andrikopoulou, M.; Crnosija, N.; Muscat, J.; Chavez, M.R.; Vintzileos, A.M. Second trimester marginal cord insertion is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 32, 2979–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wax, I.R; Craig, W.Y.; Pinette, M.G.; Wax, J.R. Second-Trimester Ultrasound-Measured Umbilical Cord Insertion-to-Placental Edge Distacne: Determining an Outcome-Based Threshold for Identifying Marginal Cord Insertion. J Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhouse, S.; Taylor, D.; Armitage, J.A. Is This Mine to Keep? Three-dimensional Printing Enables Active, Personalized Learning in Anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ 2019, 12, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, Y.H.; Harahsheh, A.S.; Krieger, A.; Olivieri, L.J. Usage of 3D models of tetralogy of Fallot for medical education: Impact on learning congenital heart disease. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 54–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, X.; Pan, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, B.; Xue, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, B. Feasibility Analysis of 3D Printing With Prenatal Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Fetal Abnormalities. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 41, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastawrous, S.; Wake, N.; Levin, D.; Ripley, B. Principles of three-dimensional printing and clinical applications within the abdomen and pelvis. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 2018, 43, 2809–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Yu, L.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Liang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Evaluation of placental growth potential and placental bed perfusion by 3D ultrasound for early second-trimester prediction of preeclampsia. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, H.; Song, T.; Su, C.; Chen, D. Utilizing 3D Printing Model of Placenta Percreta to Guide Obstetric Operation [3D]. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, 42S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, P. 3D Printing and Its Current Status of Application in Obstetrics and Gynecological Diseases. Bioengineering. 2023, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Niu, Y.; Sun, F.; Huang, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Three-dimensional printing and 3D slicer powerful tools in understanding and treating neurosurgical diseases. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1030081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesel, M.; Beyers, I.; Kalisz, A.; Joukhadar, R.; Wöckel1, A.; Herbert, S-L. ; Curtaz, C.; Wulff, C. A 3D printed model of the female pelvis for practical education of gynecological pelvic examination. 3D printing in medicine. 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recker, F.; Jin, L.; Veith, P.; Lauterbach, M.; Karakostas, P.; Schäfer, V.S. Development and Proof of Concept of a Low-Cost Ultrasound Training Model for Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis Using 3D Printing. Diagnostics. 2021, 11, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recker, F.; Remmersmann, L.; Jost, E.; Jimenez-Cruz, J.; Haverkamp, N.; Gembruch, U.; Strizek, B.; Schäfer, V.S. Development of a 3D-printed nuchal translucency model: a pilot study for prenatal ultrasound training. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wong, Y.H.; Yeong, C.H. Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Low-Cost Models in Medical Education and Clinical Practice. Micromachines. 2023, 14, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wee, C. 3D Printed Models in Cardiovascular Disease: An Exciting Future to Deliver Personalized Medicine. Micromachines. 2022, 13, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittek, A.; Strizek, B.; Recker. F. Innovations in ultrasound training in obstetrics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024, 311, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasli, M.; Dabbagh, S.R.; Tasoglu, S.; Aydin, S. Additive manufacturing and three-dimensional printing in obstetrics and gynecology: a comprehensive review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Szary, J.; Luis, M.S.; Mikulski, S.; Patel, A.; Schulz, F.; Tretiakow, D.; Fercho, J.; Jaguszewska, K.; Frankiewicz, M.; Pawlowska, E.; et al. The Role of 3D Printing in Planning Complex Medical Procedures and Training of Medical Professionals-Cross-Sectional Multispecialty Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, G.; Shearn, A.I.; Milano, E.G. , Ordonez, M.V.; Nieves, M.; Forte, V.; Caputo, M.; Schievano, S.; Mustard, H.; Wray, J.; Biglino, G. The use of 3D-printed models in patient communication: a scoping review. J. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 6, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Squelch, A.; Sun, Z. Investigation of the Clinical Value of Four Visualization Modalities for Congenital Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglino, G.; Koniordou, D.; Gasparini, M.; Capelli, C.; Leaver, L-K. ; Khambadkone, S.; Schievano, S.; Taylor, A.M.; Wray, J. Piloting the Use of Patient-Specific Cardiac Models as a Novel Tool to Facilitate Communication During Cinical Consultations. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017, 38, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, K.; Liu, L.; FU, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, A.; He, Y. 3D Printing of Physical Organ Models: Recent Developments and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2101394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, I.; Gupta, A.; Ihdayhid, A.; Sun, Z. Clinical Applications of Mixed Reality and 3D Printing in Congenital Heart Disease. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coté, J.J.; Coté, B.P.; Badura-Brack, A.S. 3D printed models in pregnancy and its utility in improving psychological constructs: a case series. 3D printing in medicine. 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coté JJ, Thomas B, Marvin J. Improved maternal bonding with the use of 3D-printed models in the setting of a facial cleft. J. 3D Print. Med. 2018, 2, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A-G. Statistical power analyses using GPower 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, I.; Sun, Z. Dimensional accuracy and clinical value of 3d printed models in congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Quayle, M.R.; Adams, J.W.; Bertram, J.F.; McMenamin, P.G. Three-Dimensional Printing of Archived Human Fetal Material for Teaching Purposes. Anat. Sci. Edu. 2019, 12, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, H.; Hansen, K.; Nørgård, M,Ø. ; Wang, T.; Pedersen, M. From tissue to silicon to plastic: three-dimensional printing in comparative anatomy and physiology. R. Soc. open sci. 2016, 3, 150643–150643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadeed, K.; Acar, P.; Dulac, Y.; Cuttone, F.; Alacoque, X.; Karsenty, C. Cardiac 3D printing for better understanding of congenital heart disease. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 111, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Pan, Z. Wu, Y.; Gu, Z.; Li, M.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yao, Y.; Shui, W.; Shen, Z.; et al. The role of three-dimensional printed models of skull in anatomy education: a randomized controlled trail. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 575. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, S.A.; Brace, E.J.; Hall, A.J.; Morrison, R.G.; Patel, D.V.; Yuh, J.Y.; Brolis, N.V. 3-D modeling applications in ultrasound education: a systematic review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 48, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Han, B.; Tang, J.; Kang, C.; Zhang, N.; Xu, Y. Full color 3D printing of anatomical models. Clin. Anat. 2022, 35, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFUMB/ISUOG Statement on the Safe Use of Doppler Ultrasound During 11–14 Week Scans (or Earlier in Pregnancy). Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2013, 39, 373.

- Clark, A.E.; Biffi, B.; Sivera, R.; Dall’Asta, A.; Fessey, L.; Wong, T.-L.; Paramasivam, G.; Dunaway, D.; Schievano, S.; Lees, C, C. Developing and testing an algorithm for automatic segmentation of the fetal face from three-dimensional ultrasound images. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Ding, C.; Xu, H.; Huang, T.; Kang, D.; Wang, D. Three-Dimensional Printed Models in Anatomy Education of the Ventricular System: A Randomized Controlled Study. World Neurosurg 2019, 125, 891–901. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

3D static ultrasound images used to create the 3D model of (a) NCI (b) MCI and (c) VCI. NCI-normal cord insertion, MCI-marginal cord insertion, VCI-velamentous cord insertion.

Figure 1.

3D static ultrasound images used to create the 3D model of (a) NCI (b) MCI and (c) VCI. NCI-normal cord insertion, MCI-marginal cord insertion, VCI-velamentous cord insertion.

Figure 2.

3D image segment editor demonstrating (a) coronal, (c) sagittal and (d) axial planes derived from the imported 3D static ultrasound image of a NCI. (b) demonstrates the 3DPM preview. Green=uterus, yellow=placenta, blue=fetus, red=umbilical cord. NCI-normal cord insertion.

Figure 2.

3D image segment editor demonstrating (a) coronal, (c) sagittal and (d) axial planes derived from the imported 3D static ultrasound image of a NCI. (b) demonstrates the 3DPM preview. Green=uterus, yellow=placenta, blue=fetus, red=umbilical cord. NCI-normal cord insertion.

Figure 3.

3D segmented STL files for the VCI model (a) fetus, (b) cord, (c) placenta and (d) uterus.

Figure 3.

3D segmented STL files for the VCI model (a) fetus, (b) cord, (c) placenta and (d) uterus.

Figure 4.

Progression of the NCI 3DPM construction. NCI-normal cord insertion, 3DPM-3D printed model.

Figure 4.

Progression of the NCI 3DPM construction. NCI-normal cord insertion, 3DPM-3D printed model.

Figure 5.

The completed 3D printed models representing (a) NCI, (b) MCI, (c) VCI and (d) close up of the VCI inserting into the fetal membranes. NCI-normal cord insertion, MCI-marginal cord insertion, VCI-velamentous cord insertion.

Figure 5.

The completed 3D printed models representing (a) NCI, (b) MCI, (c) VCI and (d) close up of the VCI inserting into the fetal membranes. NCI-normal cord insertion, MCI-marginal cord insertion, VCI-velamentous cord insertion.

Figure 6.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving confidence in assessing the PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 6.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving confidence in assessing the PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 7.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving the understanding of the structural relationships between the PCI and placenta (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 7.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving the understanding of the structural relationships between the PCI and placenta (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 8.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving ability to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 8.

Rating of the 3DPMs in improving ability to spatially visualise the placenta and PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 9.

Rating of the usefulness of 3DPMs of the PCI in ultrasound education (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 9.

Rating of the usefulness of 3DPMs of the PCI in ultrasound education (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 10.

Rating of participant recommendation of 3DPMs of the PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Figure 10.

Rating of participant recommendation of 3DPMs of the PCI (%). 1-5 indicates Likert scale.

Table 1.

The mean ratings for participant confidence and ability to spatially visualise the PCI, pre demonstration.

Table 1.

The mean ratings for participant confidence and ability to spatially visualise the PCI, pre demonstration.

Question

Please rate your… |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean (SD) |

| Confidence in assessing the PCI with ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

3.87 (1.01) |

| Confidence in identifying NCI with ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

4.03 (0.98) |

| Confidence in identifying MCI with ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

3.79 (1.02) |

| Confidence in identifying VCI with ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

3.58 (1.03) |

| Ability to spatially visualise placenta and PCI while performing ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

4.00 (1.00) |

| Ability to spatially visualise placenta and NCI while performing ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

4.09 (1.10) |

| Ability to spatially visualise placenta and MCI while performing ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

3.84 (1.08) |

| Ability to spatially visualise placenta and VCI while performing ultrasound |

1 |

5 |

3.55 (1.15) |

Table 2.

Ranking for method of demonstration for each PCI type (n = 33).

Table 2.

Ranking for method of demonstration for each PCI type (n = 33).

| PCI type |

|

Ranking 1 n (%) |

Ranking 2 n (%) |

Ranking 3 n (%) |

| NCI |

Image |

27 (81.8) |

3 (9.1) |

3 (9.1) |

| |

Video |

3 (9.1) |

23 (69.7) |

7 (21.2) |

| |

Model |

3 (9.1) |

7 (21.2) |

23 (69.7) |

| MCI |

Image |

26 (78.8) |

5 (15.2) |

2 (6.1) |

| |

Video |

3 (9.1) |

24 (72.7) |

6 (18.2) |

| |

Model |

4 (12.1) |

4 (12.1) |

25 (75.8) |

| VCI |

Image |

28 (84.8) |

2 (6.1) |

3 (9.1) |

| |

Video |

0 |

29 (87.9) |

4 (12.1) |

| |

Model |

5 (15.2) |

2 (6.1) |

26 (78.8) |

Table 3.

Mean ratings of the 3DPMs based on participants’ responses.

Table 3.

Mean ratings of the 3DPMs based on participants’ responses.

Question:

Please rate your… |

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Average |

Mean |

SD |

| Confidence in assessing the PCI with ultrasound |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.84 |

1.14 |

| Confidence in assessing a NCI with ultrasound |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.73 |

1.28 |

| Confidence in assessing a MCI with ultrasound |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.84 |

1.23 |

| Confidence in assessing a VCI with ultrasound |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

4.36 |

0.89 |

| Understanding of the structural relationship between the placenta and a NCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.33 |

1.34 |

| Understanding of the structural relationship between the placenta and a MCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.82 |

1.26 |

| Understanding of the structural relationship between the placenta and a VCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

4.45 |

0.90 |

| Ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a NCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.64 |

1.41 |

| Ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a MCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

3.94 |

1.25 |

| Ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a VCI |

33 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

4.39 |

1.00 |

Table 4.

3DPMs role in improving participant confidence, understanding and ability to spatially visualise the placenta and cord insertion types according to years of experience, p-values.

Table 4.

3DPMs role in improving participant confidence, understanding and ability to spatially visualise the placenta and cord insertion types according to years of experience, p-values.

Question:

Have the 3D models improved…. |

p-value

|

| Your confidence in assessing the PCI with ultrasound? |

0.223 |

| Your confidence in identifying a NCI with ultrasound |

0.092 |

| Your confidence in identifying a MCI with ultrasound |

0.157 |

| Your confidence in identifying a VCI with ultrasound |

0.099 |

| Your understanding of the structural relationship between a NCI and the placenta |

0.906 |

| Your understanding of the structural relationship between a MCI and the placenta |

0.272 |

| Your understanding of the structural relationship between a VCI and the placenta |

1.000 |

| Your ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a NCI |

0.192 |

| Your ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a MCI |

0.714 |

| Your ability to spatially visualise the placenta and a VCI |

0.960 |

Table 7.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data.

Table 7.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data.

| Theme |

Feedback |

Total |

| Use of 3DPMs of the PCI as educational tools |

Useful teaching resources for trainees and junior staff (n=4)

Useful educational tool to explain different types of PCI (n=2) |

n=6 |

| Improved visualisation of the PCI |

Better visualisation and understanding of PCI (n=6)

The VCI model was particularly helpful (n=2) |

n=8 |

| Extended use of the 3D models |

The 3D models could help spatially visualise placental location (n=1) and placental developmental variations (n=1) |

n=2 |

| General comments |

Could be helpful in explaining our images/videos of the PCI to radiologist (n=1)

Excellent for dyslexic students who require a more visual approach to study (n=1)

The videos and 3d models pair nicely together (n=1) |

n=3 |

| Limitations |

Cost and availability (n=1) |

n=1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).