1. Introduction

Major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) are rare entities frequently associated with congenital heart defects characterised by severe, multilevel stenosis or atresia of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), pulmonary valve abnormalities, and hypoplasia of the main pulmonary artery and its branches [

1]. These complex conditions exhibit significant variability in the origins and supply routes of pulmonary blood flow. MAPCAs originate from the aorta or its primary branches and connect distally to the pulmonary arterial system, providing crucial blood supply to the lungs [

2]. Depending on the degree of underdevelopment of the native pulmonary vessels, segments of the lungs may be supplied exclusively by MAPCAs or by a dual system involving both MAPCAs and native pulmonary arteries (NPAs) [

3].

The surgical management of MAPCAs aims to achieve biventricular circulation, wherein unifocalized MAPCAs and NPAs jointly support pulmonary blood flow. Given the heterogeneity in the development of native pulmonary vessels and the anatomical variability of MAPCAs, surgical treatment often requires a staged approach. This typically involves establishing a systemic-to-pulmonary shunt with unifocalized pulmonary vessels or creating a right ventricular-to-pulmonary connection to promote adequate growth and development of the pulmonary vasculature [

4,

5].

Virtual reality (VR) and three-dimensional (3D) printing technologies have emerged as valuable tools that address the inherent limitations of conventional two-dimensional (2D) imaging modalities, allowing for more personalised and precise treatment planning. VR provides an immersive experience with genuine depth perception and the ability to manipulate anatomical models, facilitating enhanced surgical assessments and virtual training. 3D-printed models offer real-scale anatomical representations, improving communication among surgical teams and enhancing education for both medical professionals and patients' families [

6,

7].

This study aims to assess the technical feasibility, clinical benefits, and user experience of utilizing 3D virtual reality (VR) and 3D printing technologies in the preoperative planning for surgeries in patients with rare and complex congenital heart defects involving MAPCAs unifocalisation. Additionally, the effectiveness of communication with both the medical team and the patients' parents was evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, non-randomized, comparative cohort study was conducted at the University Children’s Hospital to evaluate the impact of integrating 3D printing and virtual reality (VR) technologies in preoperative planning for patients undergoing MAPCAs unifocalization. Outcomes were compared between two groups: a control group assessed with traditional imaging methods (e.g., echocardiography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) and an intervention group that additionally utilized VR and 3D printing. The decision to incorporate new technologies was based on clinical criteria and resource availability, including software licensing limitations during the testing period. Each case was reviewed by a multidisciplinary heart team to determine the diagnostic approach.

2.2. Study Population

Nine patients with complex congenital cardiac anomalies and MAPCAs undergoing unifocalization and corrective surgery between 2017 and 2023 were included. The control group (n=4) received conventional diagnostic assessment, while the intervention group (n=5) received VR and 3D printing-assisted planning. The median age at surgery was 213 days (29–306 days) for the VR/3D group and 220 days (35–340 days) for the control group. Preoperative imaging data, including computed tomography angiography (CTA) and catheterization angiography (CA), were available for all patients.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) infants diagnosed with congenital heart defects with MAPCAs-dependent pulmonary circulation, (2) candidates for primary unifocalization of MAPCAs and NPAs, (3) availability of adequate imaging data, and (4) informed parental consent. Exclusion criteria included (1) incomplete clinical data, (2) insufficient imaging quality, (3) emergent surgery that precluded preparation of 3D models or VR simulations, and (4) technical infeasibility for using 3D printing or VR.

Case selection for 3D printing and VR was determined by the heart team, prioritizing complex anatomical presentations and cases where enhanced visualization was expected to influence surgical planning. Resource limitations (e.g., restricted software licenses) also influenced patient selection.

2.4. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Baseline demographics, clinical history, and imaging data were collected for both groups. Intraoperative findings, surgical outcomes, hospital stay length, and postoperative complications were recorded prospectively. Additional data on the preparation and application of 3D models and VR were documented for the intervention group.

2.5. Survey Assessments

Parental comprehension and satisfaction were assessed post-surgery via a questionnaire. The survey included 10 statements across five domains: understanding of the child’s condition, surgical plan comprehension, communication clarity, anxiety reduction, and overall satisfaction with care. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

Medical staff from both surgical and cardiology teams completed post-operative surveys for each case. These evaluated the diagnostic method’s utility in surgical planning, confidence in the approach, and perceived impact on outcomes. The survey also contained 10 statements covering anatomy understanding, surgical preparation, intraoperative confidence, team communication, and satisfaction with VR and 3D printing. Responses were similarly rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

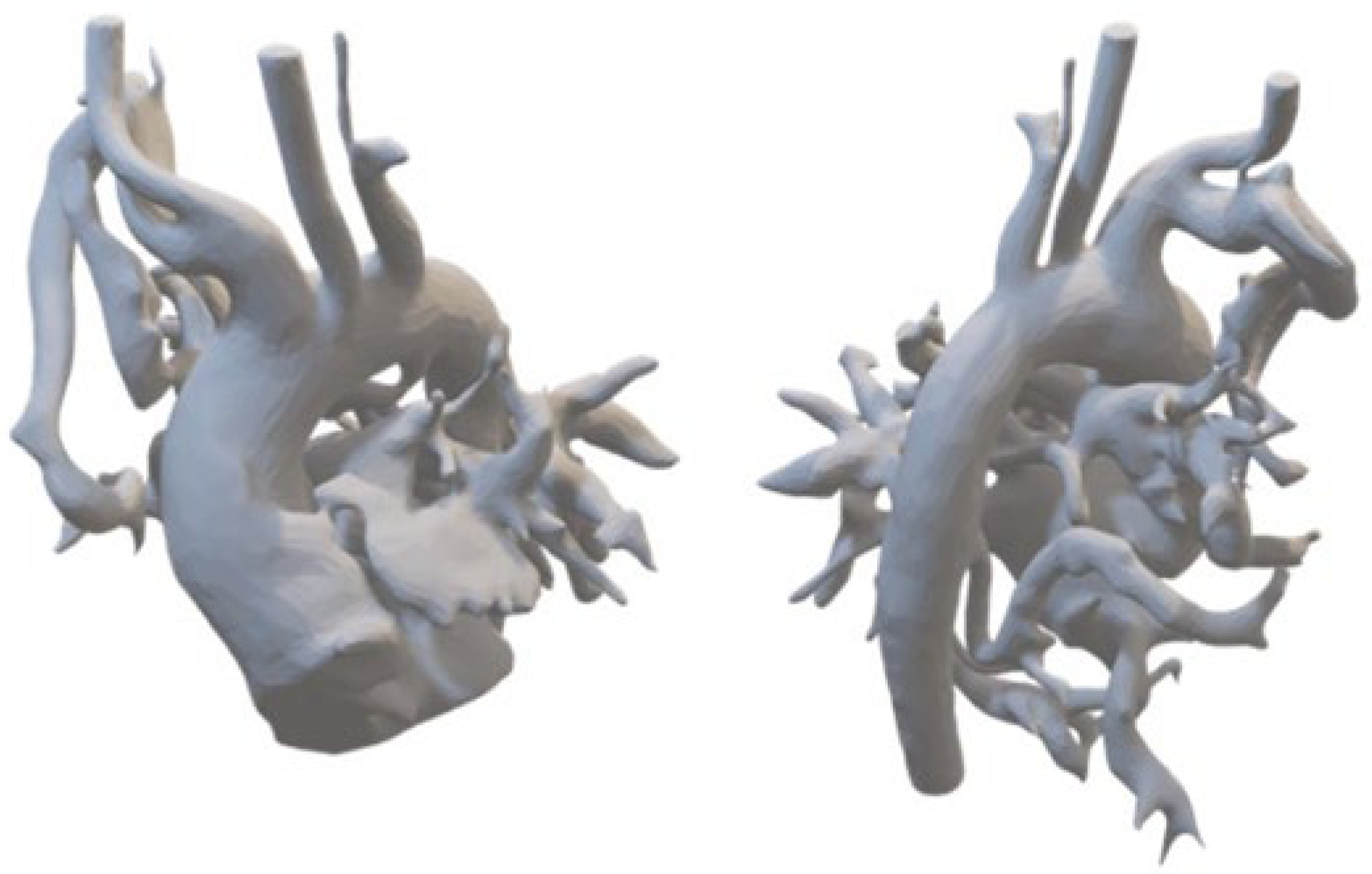

2.6. D Printing for Personalized Anatomical Models

Patient-specific CT data saved in DICOM format were segmented using 3D Slicer software, with further refinements for stabilizing elements and design adjustments. Final files compatible with 3D printing were generated using FDM printing techniques (Orca Slycer) and printed using high-resolution 3D printing technologies (

Figure 1).

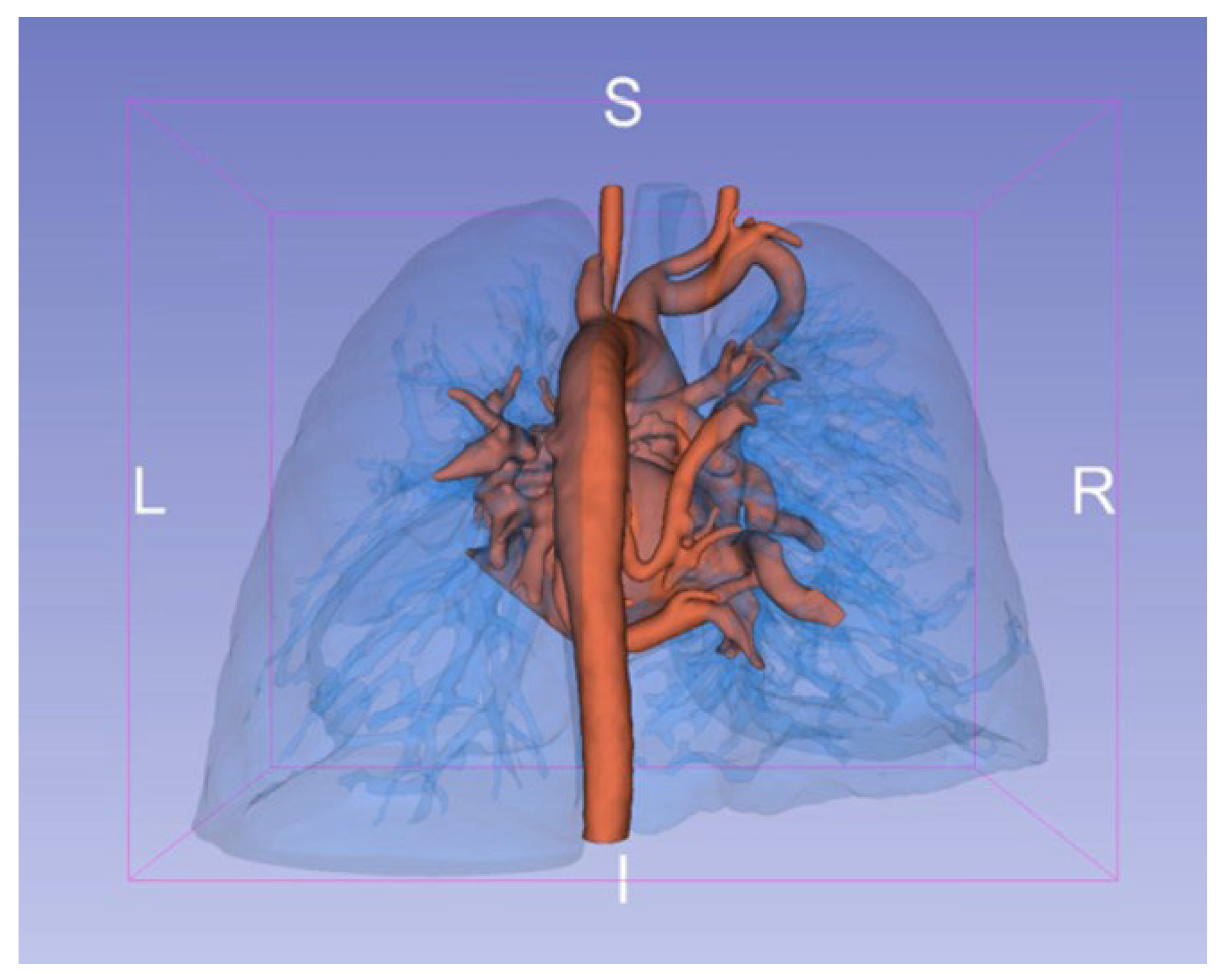

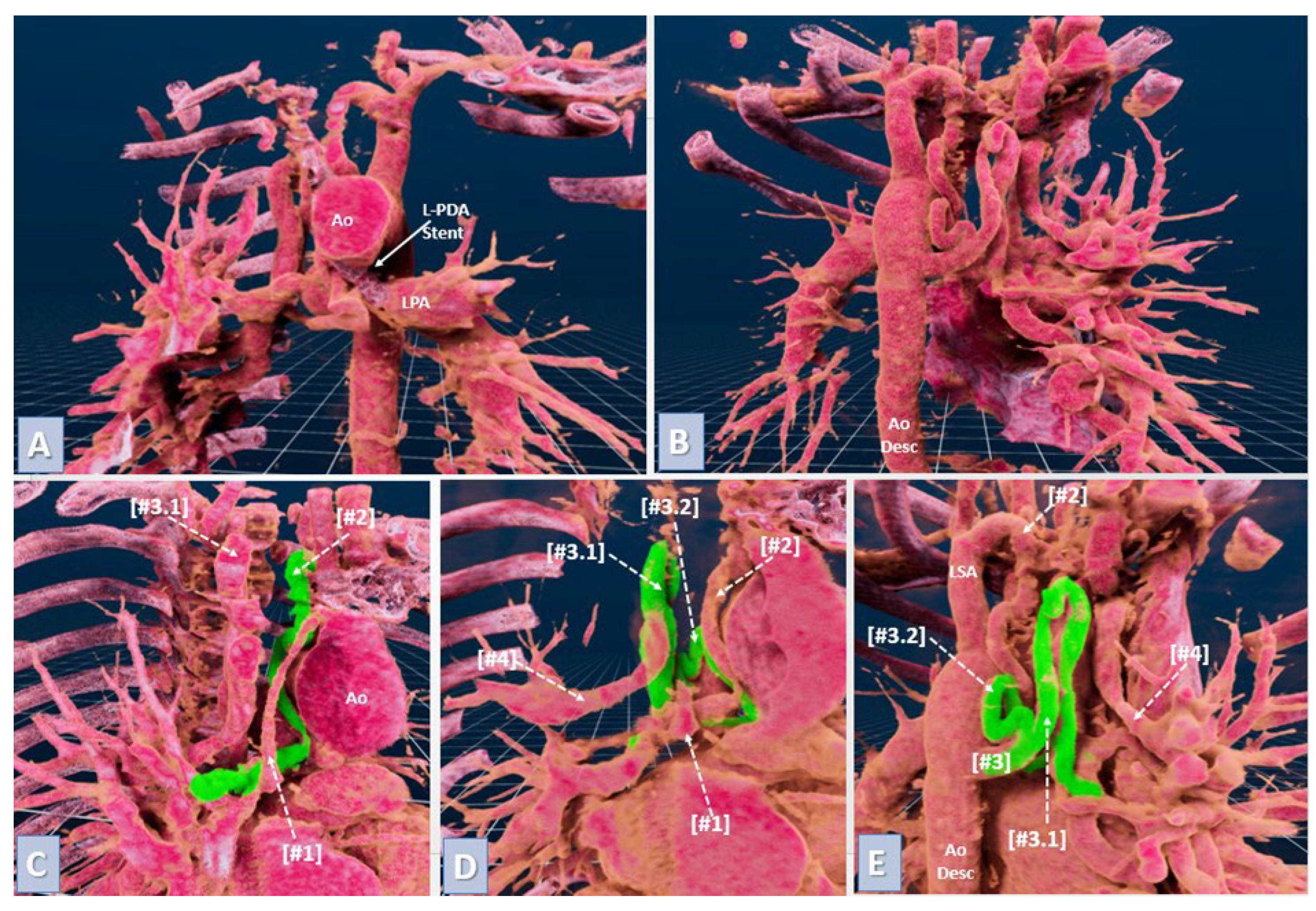

2.7. Virtual Reality for Immersive Simulation

VR models were created from preoperative CTA scans in DICOM format using automated segmentation to enhance visualization of key structures like pulmonary artery branches and MAPCAs. These data were imported into VR software, creating an interactive 3D environment reviewed by an experienced physician to confirm anatomical accuracy (

Figure 2). Surgeons interacted with the VR models using headsets and controllers, providing a fully immersive planning experience (

Figure 3).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous not normally distributed variables or mean ± SD for normal distributions. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between the intervention and control groups, while Fisher's exact test analyzed categorical variables. The effect size for the difference in operative and cardiopulmonary bypass times as well as intensive care unit recovery time and hospitalisation time between the intervention and control groups was evaluated using Cliff’s delta and a permutation test to confirm statistical significance. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using Statistica 13 software.

3. Results

3.1. Enhanced Surgical Precision and Reduced Operative Time

All patients in both VR/3D printing and control groups underwent midline sternotomy and primary unifocalization of all MAPCAs and native pulmonary arteries with cardiopulmonary bypass. Cardioplegic cardiac arrest was performed to facilitate right ventriculotomy, VSD assessment, and RV–PA conduit implantation. During the procedure, MAPCAs were carefully mobilized and gathered in the middle inferior mediastinum. In two cases, a large MAPCA was routed through the mediastinal pleura to anastomose end-to-end with a native pulmonary artery or a reconstructed neo-pulmonary trunk. Most MAPCAs were repositioned and anastomosed end-to-side or side-to-side with properly cut, hypoplastic pulmonary branches. Narrow MAPCAs were widened with a pulmonary homograft patch to optimize blood flow. After completing the anastomoses, the neo-pulmonary trunk was reconstructed with a homograft, and the right ventricular outflow tract was connected using a reinforced PTFE vessel or a valved RV–PA conduit tailored to patient size.

The integration of 3D printing and VR signifficantly reduced operative and bypass times as wel as ICU time. The intervention group demonstrated a shorter operative time (6.5 hours versus 8.3 hours) with Cliff’s delta calculated at −0.88, indicating a large effect size favoring the intervention. The permutation test yielded a statistically significant difference with a p-value of p=0.022. Similarly, a reduction in cardiopulmonary bypass time was observed in the intervention group (126 minutes versus 158 minutes), with Cliff’s delta of −0.84, reflecting a large effect size. The permutation test result was significant, with a p-value of p=0.03. The intervention group experienced shorter postoperative intensive care time, with a Cliff’s delta of −0.84, also representing a large effect size. The permutation test yielded a p-value of p=0.039, indicating statistical significance (

Table 1).

3.2. Educational Impact on Surgical Teams and Families

The use of VR and 3D printing offered significant educational benefits, enhancing team understanding of patient-specific anatomy and preparation for surgery. Junior team members, in particular, gained familiarity with complex cardiovascular structures through 3D models, improving their ability to assist effectively during surgery. This preparation translated into better teamwork, reduced uncertainty, and a more coordinated intraoperative environment (

Table 2).

In the VR/3D group, medical staff rated their understanding of patient-specific anatomy significantly higher (Mean ± SD: 4.75 ± 0.45) than in the control group (4.0 ± 0.75, p = 0.0318). Surgical preparation scores were also higher in the intervention group (4.6 ± 0.6 vs. 4.0 ± 0.9, p = 0.0495), and team communication and collaboration showed improvement with VR/3D use (4.75 ± 0.5 vs. 4.2 ± 0.8, p = 0.0318). The highest-rated factor in the VR/3D group was satisfaction with the technology in surgical planning (4.85 ± 0.35 vs. 4.1 ± 0.7, p = 0.0260), with trainees rating VR and 3D printing particularly positively, reflecting these technologies’ support for those in training (

Table 2).

The 3D-printed models and VR simulations also significantly improved communication with families, as they facilitated clearer explanations of congenital defects and surgical plans. Parents in the VR/3D group rated their understanding of their child’s anatomy higher (4.7 ± 0.45) than those in the control group (3.9 ± 0.85, p = 0.0245). Additionally, parents’ confidence in expected surgical outcomes and overall satisfaction were greater in the VR/3D group (4.9 ± 0.3 vs. 4.3 ± 0.6, p = 0.0215), indicating improved trust and reduced preoperative anxiety (

Table 3).

3.3. Intraoperative Guidance and Decision-Making

The availability of 3D-printed models during surgery provided a tangible reference for real-time decision-making, particularly in complex anatomical situations. These models enabled precise scaling and orientation, aiding the surgical team in performing accurate anastomoses. Combined with VR simulations, this real-time guidance helped surgeons navigate complex anatomy with confidence, contributing to successful outcomes in all VR/3D cases. Feedback indicated increased intraoperative confidence with new technologies (4.5 ± 0.5 vs. 3.8 ± 1.1).

In summary, integrating VR and 3D printing technologies demonstrated substantial benefits in surgical precision, reduced operative and bypass times, enhanced teamwork, and improved communication with families. These results underscore the potential for VR and 3D printing to transform surgical planning and education, supporting their broader application in complex congenital surgeries involving MAPCAs.

4. Discussion

The integration of 3D printing and virtual reality (VR) technologies marks a significant advancement in the management of complex congenital heart defects involving major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) [

8]. Traditional imaging methods like 2D echocardiography and computed tomography angiography (CTA) often lack the spatial details necessary for intricate preoperative planning, limiting a comprehensive understanding of three-dimensional (3D) cardiovascular structures critical for precise surgical decision-making [

9]. This study, in line with emerging evidence, underscores the transformative potential of 3D printing and VR in enhancing surgical approaches to MAPCAs unifocalization.

Recent studies have highlighted that 3D printing can address some of these imaging limitations by creating detailed, tactile models that provide a more nuanced view of spatial relationships in cardiac structures [

10,

11]. For instance, the use of 3D-printed heart models has demonstrated a significant impact on surgical planning, enabling surgeons to develop individualized strategies that align with specific anatomical challenges in patients with CHD [

12]. Our findings align with these studies; we found that 3D-printed models allowed surgeons to interact directly with patient-specific anatomy, offering crucial insights into the optimal arrangement and anastomosis of MAPCAs and native pulmonary arteries. This hands-on experience proved invaluable for accurate preoperative planning in complex cases, further supporting the established evidence that 3D printing can effectively enhance surgical strategy formulation [

13,

14].

Similarly, VR offers a distinct advantage over traditional 2D visualization by providing an immersive, 3D interactive experience that benefits surgeons and trainees alike. Prior studies have demonstrated VR’s role in enhancing diagnostic assessment accuracy and its utility as a collaborative tool for multidisciplinary teams [

15,

16]. Our findings reinforce these benefits, as VR significantly improved the surgical team’s understanding of complex cardiac anatomy, facilitating both decision-making and real-time intraoperative navigation. In alignment with earlier studies [

6], VR in our cohort enabled surgeons to rehearse procedures virtually, which likely contributed to the increased surgical confidence and reduced operative times observed. The ability to practice different approaches in a safe, virtual environment has been previously correlated with improved intraoperative confidence, an effect observed in our study as reflected in high ratings from surgical staff.

The innovative roles of 3D printing and VR in congenital heart disease surgeries have been documented by other researchers, who observed that both technologies offer additional value to cardiac surgeons and cardiologists by enhancing spatial visualization beyond the scope of traditional 2D imaging [

17]. Specifically, our findings indicated that 3D printing provided a tangible model for studying static anatomical structures, while VR allowed dynamic, immersive simulations that aided in surgical planning. These complementary roles were particularly evident in their impact on team communication and collaboration, as VR enabled a shared virtual exploration of complex anatomical structures. This cohesive teamwork benefit aligns with studies by Lau et al. [

7] and Chessa et al. [

18], both of whom highlighted the potential of VR to improve intraoperative coordination. Moreover, the combined data from staff and parental surveys illustrated the added educational and communicative value of these technologies. In the VR/3D group, the surgical team reported higher confidence in their understanding of anatomy, surgical preparation, and communication (

Table 2), resulting in better operative and bypass times and shorter ICU time (

Table 1). Parents in the VR/3D group also demonstrated improved comprehension of their child’s anatomy and procedure, which likely contributed to reduced preoperative anxiety and greater satisfaction with care (

Table 3).

4.1. Educational Impact and Team Collaboration

One of VR’s most significant contributions to surgical education lies in its immersive, interactive, and cost-effective nature. Multiple studies [

19,

20] have reported VR’s potential in surgical training, particularly in facilitating skill acquisition through repetitive practice in a risk-free setting. Such training can address the limitations of traditional "see one, do one, teach one" approaches, helping to reduce medical errors and enhance patient safety. Our study demonstrated VR’s effectiveness in educating junior staff, who used VR and 3D models to familiarize themselves with complex cardiovascular structures. VR’s immersive quality also enabled improved team cohesion, allowing all members to share a unified understanding of the surgical approach, reducing uncertainty and enhancing coordination. This finding resonates with prior studies that showed VR’s potential to foster teamwork and build confidence through hands-on virtual practice [

21].

Furthermore, our study highlighted the educational and communication benefits of VR and 3D printing for the families of patients. Research by Zhao et al. [

11] and Yoo et al. [

9] has shown that both technologies aid in explaining complex procedures to families, fostering trust and understanding. In our cohort, parents in the VR/3D group reported a higher level of understanding and satisfaction, likely due to the clearer explanations these models provided. This aligns with growing recognition of VR and 3D printing as valuable tools for family-centered care, supporting both patient education and family engagement in the treatment process.

4.2. Complementary Roles of 3D Printing and VR

While 3D printing and VR offer unique advantages, our study underscores that they are most effective when used in tandem. 3D-printed models provided a physical reference for understanding structural anatomy, particularly useful for studying static spatial relationships. In contrast, VR’s adaptability and interactivity made it ideal for simulating complex maneuvers, offering a dynamic preview of challenging surgical procedures. This dual approach supports comprehensive preoperative assessments and reinforced anatomical understanding, illustrating that 3D printing and VR are complementary, not interchangeable, in CHD surgery.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite promising results, our study is limited by its small sample size, tied to the preliminary nature of introducing these technologies with restricted accessibility. This limitation constrains the generalizability of our findings, and further research with larger patient cohorts is needed to validate these observations. Future studies should also prioritize developing standardized protocols for 3D printing and VR in CHD surgery to ensure consistent outcomes across clinical settings and improve cost-effectiveness.

In addition, expanding VR capabilities to simulate team dynamics through multi-user platforms could further enhance collaborative practice. Broadening these technologies’ applications into postoperative care, patient education, and long-term follow-up would deepen their utility in managing complex congenital heart defects. Moreover, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning could improve the accuracy of simulations by tailoring them to each patient’s unique anatomy. As these advancements take shape, VR and 3D printing could play a pivotal role in training the next generation of cardiac surgeons, complementing traditional methods, reducing medical errors, and improving patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of 3D printing and VR technologies in preoperative planning for complex congenital heart surgeries involving MAPCAs demonstrated enhanced surgical precision, reduced operative and intensive care times, and improved educational experiences for surgical teams and families. These findings support the broader integration of VR and 3D printing as valuable tools in routine clinical practice, advancing personalized and precise treatment strategies for congenital heart conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.; methodology, J.K.; software, K.G.; investigation, J.Sz.; resources, A.R.; data curation, K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Jagiellonian University (118.6120.09.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interes.

References

- Ryan JR, Moe TG, Richardson R, Frakes DH, Nigro JJ, Pophal S. A novel approach to neonatal management of tetralogy of Fallot, with pulmonary atresia, and multiple aortopulmonary collaterals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1):103-4. [CrossRef]

- Seale, A.N.; Ho, S.Y.; Shinebourne, E.A.; Carvalho, J.S. Prenatal identification of the pulmonary arterial supply in tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia. Cardiol. Young- 2009, 19, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Z.; McElhinney, D.B.; Reddy, V.; Moore, P.; Hanley, F.L.; Teitel, D.F. Coronary to pulmonary artery collaterals in patients with pulmonary atresia and ventricular septal defect. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trezzi, M.; Cetrano, E.; Albanese, S.B.; Borro, L.; Secinaro, A.; Carotti, A. The Modern Surgical Approach to Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries. Children 2022, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikai, A. Surgical strategies for pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect associated with major aortopulmonary collateral arteries. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 66, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.S.; Krishnan, A.; Huang, C.Y.; Spevak, P.; Vricella, L.; Hibino, N.; Garcia, J.R.; Gaur, L. Role of virtual reality in congenital heart disease. Congenit. Hear. Dis. 2018, 13, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, I.; Gupta, A.; Sun, Z. Clinical Value of Virtual Reality versus 3D Printing in Congenital Heart Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulos, A.A.; Mitsouras, D.; Yoo, S.-J.; Liu, P.P.; Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Rybicki, F.J. Applications of 3D printing in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.J.; Hussein, N.; Peel, B.; Coles, J.; van Arsdell, G.S.; Honjo, O.; Haller, C.; Lam, C.Z.; Seed, M.; Barron, D. 3D Modeling and Printing in Congenital Heart Surgery: Entering the Stage of Maturation. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappanayil, M.; Koneti, N.R.; Kannan, R.R.; Kottayil, B.P.; Kumar, K. Three-dimensional-printed cardiac prototypes aid surgical decision-making and preoperative planning in selected cases of complex congenital heart diseases: Early experience and proof of concept in a resource-limited environment. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017, 10, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gong, X.; Ding, J.; Xiong, K.; Zhuang, K.; Huang, R.; Li, S.; Miao, H. Integration of case-based learning and three-dimensional printing for tetralogy of fallot instruction in clinical medical undergraduates: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R.M.; Jolley, M.A.; Mascio, C.E.; Chen, J.M.; Fuller, S.; Rome, J.J.; Silvestro, E.; Whitehead, K.K. Clinical 3D modeling to guide pediatric cardiothoracic surgery and intervention using 3D printed anatomic models, computer aided design and virtual reality. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valverde, I.; Gomez-Ciriza, G.; Hussain, T.; Suarez-Mejias, C.; Velasco-Forte, M.N.; Byrne, N.; Ordoñez, A.; Gonzalez-Calle, A.; Anderson, D.; Hazekamp, M.G.; et al. Three-dimensional printed models for surgical planning of complex congenital heart defects: an international multicentre study. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2017, 52, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, S.; Rockefeller, T.; Raptis, D.A.; Woodard, P.K.; Eghtesady, P. 3D Printing Provides a Precise Approach in the Treatment of Tetralogy of Fallot, Pulmonary Atresia with Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, A.H.; el Mathari, S.; Abjigitova, D.; Maat, A.P.M.; Taverne, Y.J.J.; Bogers, A.J.C.; Mahtab, E.A. Current and Future Applications of Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality in Cardiothoracic Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 113, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, F.; Vida, V.; Godard, C.; Bertelli, F.; Reffo, E.; Boddaert, N.; El Beheiry, M.; Masson, J. Fast-track virtual reality for cardiac imaging in congenital heart disease. J. Card. Surg. 2021, 36, 2598–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, J.J.; Bakhuis, W.; Sadeghi, A.H.; Veen, K.M.; Roest, A.A.W.; Bruining, N.; van Walsum, T.; Hazekamp, M.G.; Bogers, A.J.J.C. Optimized preoperative planning of double outlet right ventricle patients by 3D printing and virtual reality: a pilot study. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chessa M, Van De Bruaene A, Farooqi K, Valverde I, Jung C, Votta E, et al. Three-dimensional printing, holograms, computational modelling, and artificial intelligence for adult congenital heart disease care: an exciting future. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(28):2672-84. [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.Q.; Lan, L.; Kay, J.; Lohre, R.; Ayeni, O.R.; Goel, D.P.; de Sa, D. Immersive Virtual Reality for Surgical Training: A Systematic Review. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 268, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulijala Y, Ma M, Pears M, Peebles D, Ayoub A. Effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Reality in Surgical Training-A Randomized Control Trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(5):1065-72. [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.Y.; Ooi, S.W.; Bin Rusli, K.D.; Lau, T.C.; Tam, W.W.S.; Chua, W.L. Nurse-Physician Communication Team Training in Virtual Reality Versus Live Simulations: Randomized Controlled Trial on Team Communication and Teamwork Attitudes. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).