1. Introduction

The challenges associated with diagnosing and treating vascular disease are many and diverse. The complexity of each patient’s disease morphology, the variations in thrombus and calcification and its’ deposition in blood vessels, variations in patient anatomy, tortuosity of access vessels and hostile environments make intervention multifaceted and risky. The current practice of endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) relies on two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) CT imaging visualisations and this meets most of the current requirements for planning the EVAR. However, there is a lack of realistic 3D relationship between complex vascular disease and anatomical structures [

1]. When 3D printing technology is implemented to produce patient-specific or personalised models, it has the potential to overcome the limitations of currently used 2D and 3D visualisations owing to its superiority of presenting realism of 3D perception of anatomical structures in relation to pathology, in addition to the advantages of tactile experience.

It is purported that clinician skills can be optimised where 3D printed models are introduced for training and procedural simulation [

2]. 3D printed cardiac models have been produced for teaching anaesthetic residents and fellows anatomy and pathology and for planning surgical interventions [

3]; while 3D printed personalised vascular models (3DPPVM) are being utilised for pre-surgical planning and simulation of EVAR [

4,

5,

6,

7]. 3DPPVM models are patient-specific with high accuracy, addressing the variances between vessels and anatomical structures, and previous studies reported its great value in assisting the challenging situations such as planning fenestrated stent-grafts [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Earlier research indicates that in high-acuity, low-occurrence (HALO) patient presentations, 3DPPVM are shown to be a good teaching tool for a tangible experience [

12]; simulate EVAR procedural steps with high fidelity [

13], and serve as a training tool to guide interventions in patients with complex cardiovascular anatomy and pathology [

14]. The application of 3DPPVM in simulating interventional radiology procedures is reinforced by its value as a learning medium to perform diagnostic radiology procedures and simulate endovascular or interventional procedures [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], leading to the reduction of intervention time with a higher level evidence achieved through reduced procedural times.

Research publications has demonstrated the utility and clinical value of 3DPPVM in vascular conditions including aneurysm, dissection, extremity vascular disease, and other arterial diseases [

23]. However, there is still a paucity in literature on the use of these models in education and training in radiology and endovascular interventions where the environment is anatomically hostile and disease progression is compounding. There is a paradigm shift in surgical training moving from traditional methods to simulation-based approaches with the aim of developing more effective learning environments [

24]. With the advancement of the printing materials used in 3D printing, it is possible to reproduce the models with “tissue-mimicking properties” [

25]. This promotes the model’s use in simulation training, where the interventional trainee relies on the haptic feedback from the guide wires, while they direct the wires to the target vessels. Wu et al [

4] developed a personalised 3D printed aortic dissection model with testing different materials. Their results showed that Agilus A30 has the tensile strength similar to normal human aortic tissue properties with similar CT attenuation on both non-contrast and contrast-enhanced CT scans of aortic dissection. This prompted our study to produce 3DPPVM using this material as we aim to generate more realistic vascular models for education and simulation purposes. Although previous studies reported the value of 3DPPVM in surgical planning and simulation of complex surgical procedures, they were limited to including only one particular vascular anatomical region with use of 3D printing technology. Our study addresses this gap by including common vascular diseases including aortic, carotid, coronary and renal arterial diseases with developed corresponding 3D printed models.

Our primary aim of this study was to generate 3DPPVM with materials that are flexible and responsive, similar to arterial tissue properties; and to include models of abdominal aortic aneurysm, carotid artery stenosis, coronary artery and renal artery stenosis based on selected CT angiographic images. Our secondary aim of the study was to determine the clinical value of these 3DPPVM in simulating interventional vascular procedures for pre-surgical planning and treatment of these common vascular diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Strategy

A qualitative/quantitative mixed study design was conducted to ascertain the applicability of 3DPPVM by specialist clinicians. Ethics approval was obtained from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee for this study (HRE2023-0271). Four anonymized patients’ computed tomography angiography (CTA) imaging data comprising abdominal aortic aneurysm, left internal carotid artery stenosis, right coronary artery stenosis and left renal artery stenosis were selected from generation of 3DPPVM.

2.2. Generation of 3D Printed Vascular Models

Four datasets which were adequately contrast-opacified were selected for the generation of the vascular models. These covered carotid arteries, coronary arteries, abdominal aorta and renal arteries demonstrating vascular disease vividly (left internal carotid artery stenosis, right coronary artery stenosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm and left renal artery stenosis). These CTA images were segmented to remove the surrounding abdominal organs and tissues, thereby isolating the arteries of interest. 3D Slicer (V5.2) was used to process these Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data. Smoothing and hollowing algorithms were applied to the virtual model, and the virtual cutting tool was applied to open the ends of the virtual model to prevent pressure build-up during printing. An appropriate wall thickness (2mm) was added to the segmented models prior to printing to support the printing process and avoid printing errors. It was saved as an STL file (Standard Tessellation Language) (

Figure 1).

2.3. Material Selection

The STL files were printed in a variety of plastics and resins and shown to an interventional radiologist for informal discussion (

Figure 2). All the models were CT scanned in a 6% solution of Omnipaque and water to allow for acquisition of contrast enhancement similar to standard CTA (CT attenuation close to 150-300 HU) [

26]. The Hounsfield units measured on the models were compared to the Hounsfield units measured on the original patient CT scan. After the measurements of the Hounsfield units, Formlabs 50A elastic resin was selected for the final printing of the four 3DPPVM chosen for the assessment (

Figure 3). The files were exported for orientation and printing on the Formlabs 3D printer (Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) at a scale of 1:1.

2.4. Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited from both public and private hospitals, in Western Australia and Queensland, Australia through convenience sampling including snowball sampling via email invitations. Twenty-one radiology and surgical specialists were invited to participate in the study. They were asked to rank the usefulness and application of these four 3DPPVM and their attributes for use in vascular intervention. The 3DPPVM assessment took 20 minutes, including viewing of the CT DICOM images which was made available on 3D Slicer Software and operator guidance proffered. The segmented CT scans of the 4 models were made available to the participants and were viewable in coronal, axial and sagittal reconstructions, and 3D visualisations. The software ‘cutting tool’ was demonstrated for opening the virtual arterial vessel for luminal examination. After that, the participants were asked to complete a questionnaire focusing on the clinical applications of the 3DPVM with answers ranking from 1 to 5 with 5 being the highest. The questions were designed to focus on the following aspects: whether 3DPPVM present realism, display anatomical structures with high accuracy, enhance planning of interventional procedures, develop haptic skills or reduce procedure time or improve communication with clinicians, etc (Appendix 1). Limitations of 3DPPVM were also identified in one of the questions (Q18), and participants were allowed to provide further comments or suggestions in the end. They had the opportunity to rate their recommendation on the use of 3DPPVM ranking from 1 to 10 with 10 being highly recommended.

Figure 4.

Order of presentation of 3DPPVM to clinicians.

Figure 4.

Order of presentation of 3DPPVM to clinicians.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed using the IBM SPSS statistical package, version 29.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Shapiro-Wilk Test was executed to confirm the normality of the data and statistical significance was established at a p-Value of <0.05.

The two-way ANOVA test was conducted to examine whether there is any significant difference in the distribution of the independent variables of medical specialty and years of experience; against the dependent variables of the 3DPPVM realism, anatomy, disease shown, procedure, planning, simulation, haptic feedback, time of surgery, pathology to patient and pathology to health professional.

Descriptive statistics were executed to measure the mean, the range and the standard deviation across the dependent variables of the 3DPPVM realism, anatomy, disease shown, procedure, planning, simulation, haptic feedback, time of surgery, pathology to patient and pathology to health professional; against the four 3DPPVM. Descriptive statistics were also executed to measure the minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation across the most applicable use for the 3DPPVM and their most limited application.

Where participants entered a qualitative response, these were analysed thematically. T’ tests were run across the data with a 95% confidence level. Frequencies, descriptive analyses and pie charts were generated from the data collected.

3. Results

A total of 21 participants were recruited in this study, comprising 6 radiologists and 15 surgeons.

Figure 5 shows the demographics of study participants with regard to their working experience.

The mean ranks of 3DPPVM for each question is detailed in

Table 1. The highest overall scores were found in accurately displaying anatomical structures (mean ranks >4.2 for all of the four models), clarifying pathology to patients (mean ranks >4.1 for all of the four models) and clarifying pathology to health professionals (mean ranks 4.0 for aorta, carotid and coronary artery models, and 3.83 for renal artery model). The lowest mean ranks were noted in reducing procedure time and developing haptic skills with less than 3.5 and 3.5, respectively when compared to others. No significant difference was found with regard to the value of these 3DPPVM in these areas, except for the demonstration of realism and enhancement of planning of interventions, where aorta model was ranked the highest.

Further questions on the use of 3DPPVM enhancement of communication with interventional clinicians, whether 3DPPVM is feasible in a surgical setting and whether the clinician would recommend 3DPPVM to their colleagues, with the received Yes responses from those that completed these questions shown in

Table 2.

Participants were asked to rank 3DPPVM’s applications with ranking scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most important application in the areas including pre-interventional planning, pre-interventional simulation, interventional orientation, communication in medical practice, and education/training. The 3DPPVM were found to have applications in all the areas with education and training measured as the most important with a mean rank of 2.11, followed by pre-interventional planning, communication, pre-intervention simulation and interventional orientation the least applicable, as shown in

Table 3.

Participants were also asked to provide their feedback on the 3D model’s limitations with ranking scale of 1-5, with 1 being the most limited application. The most limiting factor was the lack of surrounding anatomy with a mean rank of 2.20, followed by their static nature limitation, softness, orientation for simulation and least limited for education and training (

Table 4).

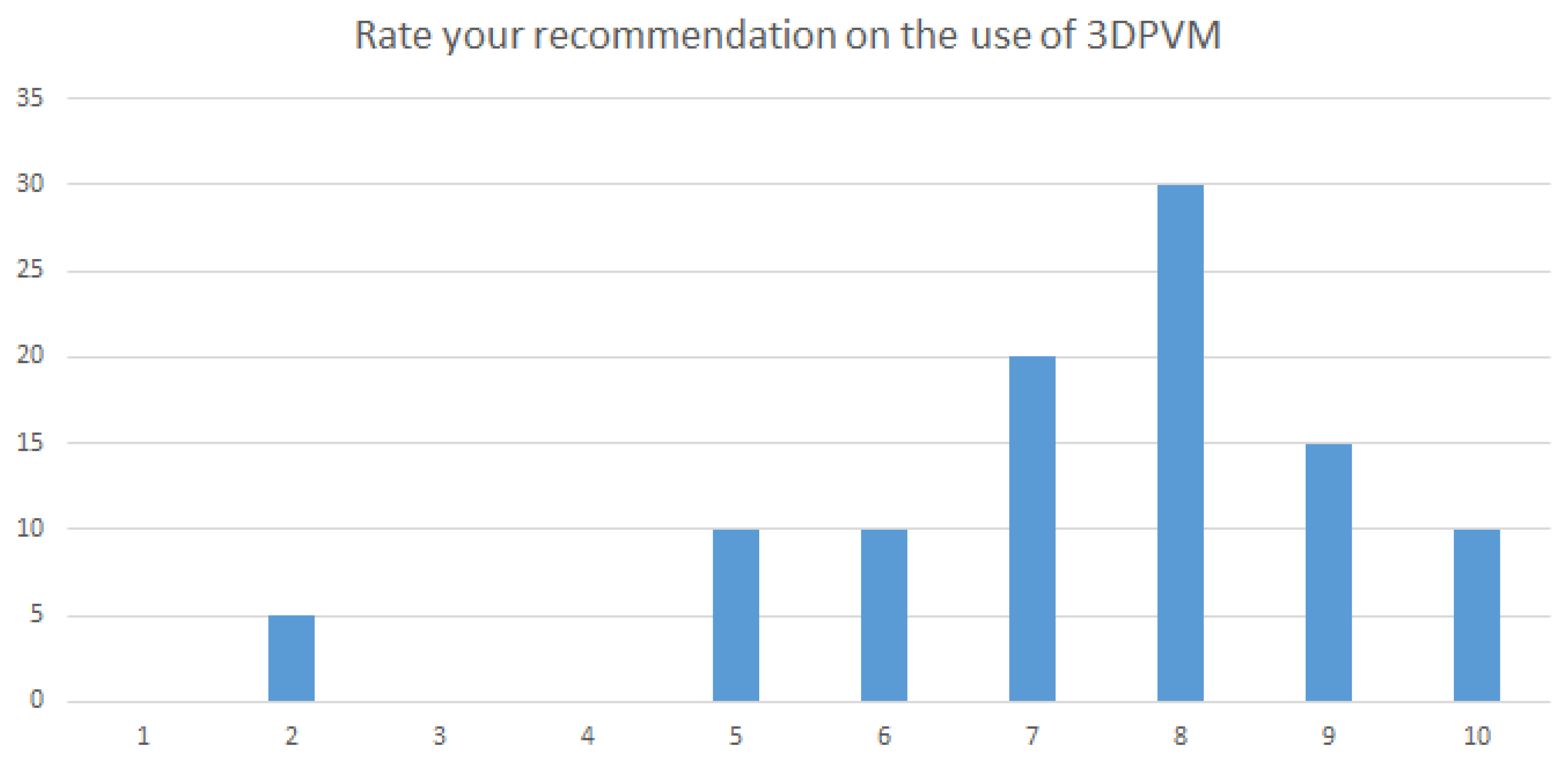

Clinicians ranked their recommendation for the use of 3DPVM on a scale of 1 to 10, where ten was the highest rank. The lowest ranking was two and the highest ranking was ten. 30% of participants ranked the models at an 8 and a cumulative value of over 75% of participants ranked the models above 7 out of 10 (

Figure 6). No qualitative response was given to indicate the reason for the low rankings.

4. Discussion

Our study shows that the 3DPPVM demonstrate good accuracy and realism as participants scored them more than 3.8 out of 5 in most of the application areas. The models developed in this study scored highly at a mean score of 4.2 to 4.3 replicating anatomy closely, a mean score of >4.2 for clarifying pathology to patients and mean score of 4.0 for clarifying pathology to health professionals. With inclusion of four different vascular models comprising common vascular pathologies, this study’s findings add valuable information to the current literature reinforcing the usefulness of 3DPPVM in cardiovascular disease.

3D printed vascular models are showing great promise in the medical education, pre-surgical planning and simulation of complex endovascular procedures [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

17,

18,

21,

22,

23,

24,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The 3D printed models are not only highly accurate, but also possessing high haptic and fluoroscopic fidelity which makes them suitable for training and simulation purposes. Coles-Black et al performed a systematic review of 9 studies focusing on the development of 3D printed templates to guide fenestrated physician-modified stent grafts [

27]. Despite limitations of the study designs in their review (5 case reports, 1 technical report and 1 letter to the editor with only 2 prospective trials), the review shows the potential value of using 3D printed templates to assist with placement of fenestrated stent grafts in patients with complex or challenging aortic aneurysms as it could lead to significant cost reduction and increasing the accuracy of fenestration alignment. This is also confirmed by a recent review on the application of 3D printed models in planning of complex aortic aneurysm repair [

10]. By comparing 3D printing guided group with non-3D printing guided group, the cardiopulmonary bypass time (170 vs 181 minutes) and total circulatory arrest time (12 vs 13.5 minutes) were reduced, while no significant changes were found in other areas such as total operative time, hospitalization duration and intensive care unit admission duration between the two groups [

10,

32]. Authors also indicated the importance of incorporating artificial intelligence into image processing and segmentation as AI-driven 3D printing will significantly reduce the time and effort required for printing these models [

32,

33].

Our study follows the previous study design with regard to the process that each participant undertook, first viewing original DICOM images, followed by presentation of 3DPPVM, then completing a short questionnaire [

34,

35]. Consistent with previous studies, 3DPPVM were scored higher in demonstrating anatomical structures and pathology, which is similar to these two reports documenting the value of 3D printed models in appreciation of complex anatomy and pathology (congenital heart defects), communication with patients and health professional, and pre-operative/intra-operative planning. In Lee’s study, 3D printed models and virtual reality were considered the preferred tools in medical education, while 3D printed models were ranked as the best communication tool when compared to other methods [

35]. These previous studies mainly focused on one particular disease, which is congenital heart disease with developed personalised models, while our study includes four different vascular diseases, thus, adding valuable information to the existing literature with regard to the clinical application of 3D printing in vascular disease.

Although our models were printed with soft material, the static nature of the 3DPPVM was recognized by some of the participants as one of the limitations that could influence their use in surgical simulation. Lack of surrounding structures was scored as the most limited factor by most of the participants. Ideally the 3D printed models should be placed in the environment with surrounding anatomical structures as shown in a study by Kaschwich et al [

29]. Authors developed patient-specific 3D printed vascular anatomy simulator which was connected to a pumping system simulating an authentic environment during the interventional procedures. Furthermore, all main abdominal arteries were drained to simulate blood flow representing realistic physiology condition. Despite inclusion of different vascular diseases in our 3DPPVM, this limitation should be addressed in future studies as most of the currently used 3D printed models lack of surrounding anatomical environment [

36].

Some of limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, this small cohort of participants could be expanded to include more clinicians from different specialties such as including interventional cardiologists, vascular residents, etc. Second, as highlighted previously, our 3D printed models lack of simulating hemodynamic flow, thus restricting its application to some extent when performing endovascular stent grafting procedures. This should be considered in future studies to optimise the training outcomes as operators will experience realistic haptic feeling when placing guide wires or catheters into the vascular system. Third, our selected cases represent common pathologies, such as abdominal aortic aneurysm, and artery stenosis which could be simple not reflecting more complex or challenging vascular anomalies. Future studies should include differing degrees of plaque and thrombus to make the models more realistic in their pliability and conformation when being evaluated for stent-graft access. Major factors affecting the advancement of the delivery systems include the tortuosity of the vessel and how the variances in calcification density will need to be included in the future model design.

5. Conclusions

In this study we developed personalised 3DPPVM with high accuracy of replicating the patient anatomy and disease morphology. Results showed that 3DPPVM serve as educational tools in medical education and training, as well as pre-operative simulation of endovascular procedures. With further improvement of model design, 3D printing technology will continue to play an important role in simulating endovascular stent grafting procedures with reduction of procedure-related risks or complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.L.D and Z.S.; Writing – original and draft preparation, D.L.D.; Project administration-Z.S.; Project supervision- Z.S.; Writing – review and editing, D.L.D. and Z.S.

Funding

This work was funded by the Royal Perth Hospital Imaging Grant, Perth, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Curtin University (approval number: HRE2023-0271) and carried out to align with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Guy Tomlinson from Rockingham Hospital, Western Australia for assisting with CT scanning of models, and Carl Lares from Curtin University for printing the 3D vascular models.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yaprak, F.; Ozer, M.A.; Govsa, F.; Cinkooglu, A.; Pinar, Y.; Gokmen, G. Prespecialist perceptions of three-dimensional heart models in anatomical education. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2023, 45, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvini, S.; Raunig, I.; Demi, L.; Spadoni, N.; Tasselli, S. Unsuspected limitations of 3D printed model in planning of complex aortic aneurysm endovascular treatment. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 58, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango, S.; Gorbaty, B.; Brigham, J.; Iaizzo, P.A.; Perry, T.E. A role for ultra-high resolution three-dimensional printed human heart models. Echocardiography. 2023, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.A; Squelch, A.; Sun, Z. Investigation of three-dimensional printing materials for printing aorta model replicating type B aortic dissection. Curr. Med. Imaging. 2021, 17, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynio, P.; Kazimierczak, A.; Jedrzejczak, T.; Gutowski, P. A 3-dimensional printed aortic arch template to facilitate the creation of physician-modified stent-grafts. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2018, 25, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynio, P.; Wojtun, M.; Wojcik, K.; Kawa, M.; Falkowski, A.; Gutowski, P.; Kazimierczak, A. The accuracy and reliability of 3D printed aortic templates: a comprehensive three-dimensional analysis. Quant. Imaging. Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Hu, C.; Huang, S.; Long, W.; Wang, Q.; Xu, G.; Liu, S.; Qang, B.; Zhang, L.; li, L. An innovative customized stent graft manufacture system assisted by three-dimensional printing technology. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 112, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Huayuan, X.; Zhu, F.; Cheng, C.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Shen, K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Q.; et al. Clinical comparative analysis of 3D printing-assisted extracorporeal pre-fenestration and Castor integrated branch stent techniques in treating type B aortic dissections with inadequate proximal landing zones. BMC. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Zhu, F.; Cheng, C.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; He, X.; Lu, Q.; Xi, H.; Shen, K.; Yu, H. 3D Printing-Assisted versus Conventional Extracorporeal Fenestration Tevar for Stanford Type B Arteries Dissection with Undesirable Proximal Anchoring Zone: Efficacy Analysis. Heart. Surg. Forum. 2023, 26, E363–E371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Choi, P.; Ku, J.C.; Vergara, R.; Malgor, R.; Patel, D.; Li, Y. Application of three-dimensional printing in the planning and execution of aortic aneurysm repair. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 11, 1485267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.S.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Wang, C.; Shi, Y.H.; Zhou, M.J.; Zhao, J.X.; Liu, C.; Qiao, T.; Liu, C. J, et al. Three-dimensional printing to guide fenestrated/branched TEVAR in triple aortic arch branch reconstruction with a curative effect analysis. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024, 31, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudie, C.; Kinnin, J.; Bartellas, M.; Gullipalli, R.; Dubrowski, A. The Use of 3D printed vasculature for simulation-based medical education within interventional radiology. Cureus 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkkainen, J.; Sandri, G.; Tenorio, E.R.; Alexander, A.; Bjellum, K.; Matsumoto, J.; Morris, J.; Mendes, B.C.; DeMartino, R.R.; Oderich, G.S. Simulation of Endovascular Aortic Repair Using 3D Printed Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Model and Fluid Pump. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2019, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, B.; Illi, J.; Gloeckler, M.; Pilgrim, T.; Praz, F.; Windecker, S.; Haeberlin, A.; Grani, C. Imaging-Based, Patient-Specific Three-Dimensional Printing to Plan, Train, and Guide Cardiovascular Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart. Lung. Circ. 2022, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, G.; Anggrahini, D.W.; Rismawanti, R.I.; Fatimah, V.A.N.; Hakim, A.; Hidayah, R.N.; Gharini, P.P.R. 3D-Printing-Based Fluoroscopic Coronary Angiography Simulator Improves Learning Capability Among Cardiology Trainees. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2023, 14, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wee, C. 3D printed models in cardiovascular disease: An exciting future to deliver personalized medicine. Micromachines (Basel). 2022, 13, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catasta, A.; Martini, C.; Mersanne, A.; Foresti, R.; Bianchini Massoni, C.; Freyrie, A.; Perini, P. Systematic Review on the Use of 3D-Printed Models for Planning, Training and Simulation in Vascular Surgery. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paessler, A.; Forman, C.; Minhas, K.; Patel, P.A.; Carmichael, J.; Smith, L.; Jaradat, F.; Assia-Zamora, S.; Arslan, Z.; Calder, F.; et al. 3D printing: a useful tool for safe clinical practice in children with complex vasculature. Arch. Dis. Child. 2024, 109, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Brito, J.; Rodrigues, T.; Santiago, H.; Ricardo, D.; Cardoso, P.; Pinto, F.J.; Silva Marques, J. Intravascular imaging modalities in coronary intervention: Insights from 3D-printed phantom coronary models. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2023, 42, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiser, K.; Sollmann, N.; Renz, M.; Kreiser, K.; Sollmann, N.; Renz, M. Importance and potential of simulation training in interventional radiology. Rofo. 2023, 195, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrzejczak, K.; Antonowicz, A.; Butruk-Raszeja, B.; Orciuch, W.; Wojtas, K.; Piasecki, P.; Narloch, J.; Wierzbicki, M.; Makowski, L. Three-Dimensionally Printed Elastic Cardiovascular Phantoms for Carotid Angioplasty Training and Personalized Healthcare. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersanne, A.; Foresti, R.; Martini, C.; Caffarra Malvezzi, C.; Rossi, G.; Fornasari, A.; De Filippo, M.; Freyrie, A.; Perini, P. In-House Fabrication and Validation of 3D-Printed Custom-Made Medical Devices for Planning and Simulation of Peripheral Endovascular Therapies. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Chadalavada, S.C.; Ghodadra, A.; Ali, A.; Arribas, E.M.; Chepelev, L.; Ionita, C.N.; Ravi, P.; Ryan, J.R.; Santiago, L.; et al. Clinical situations for which 3D Printing is considered an appropriate representation or extension of data contained in a medical imaging examination: vascular conditions. 3D. Print. Med. 2023, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresti, R.; Fornasari, A.; Claudio Bianchini, M.; Mersanne, A.; Martini, C.; Cabrini, E.; Freyrie, A.; Perini, P. Surgical Medical Education via 3D Bioprinting: Modular System for Endovascular Training. Bioengineering. 2024, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, R.; Zech, C.J.; Takes, M.; Brantner, P.; Thieringer, F.; Deutschmann, M.; Hergan, K.; Scharinger, B.; Hecht, S.; Rezar, R.; et al. Vascular 3D Printing with a Novel Biological Tissue Mimicking Resin for Patient-Specific Procedure Simulations in Interventional Radiology: a Feasibility Study. J. Digit. Imaging. 2022, 35, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ng, C.K.C.; Wong, Y.H.; Yeong, C.H. 3D-printed coronary plaques to simulate high calcification in the coronary arteries for investigation of blooming artifacts. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles-Black, J.; Barber, T.; Bolton, D.; Chuen, J. A systematic review of three-dimensional printed template-assisted physician-modified stent grafts for fenestrated endovascular aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles-Black, J.; Bolton, D.; Chuen, J. Accessing 3D printed vascular phantoms for procedural simulation. Front. Surg. 2021, 7, 626212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschwich, M.; Sieren, M.; Matsiak, F.; Bouchagiar, J.; Dell, A.; Bayer, A.; Ernst, F.; Ellebrecht, D.; Kleemann, M.; Horn, M. Feasibility of an endovascular training and research environment with exchangeable patient specific 3D printed vascular anatomy: simulator with exchangeable patient-specific 3D-printed vascular anatomy for endovascular training and research. Ann. Anat. 2020, 231, 151519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grab, M.; Hundertmark, F.; Thierfelder, N.; Fairchild, M.; Mela, P.; Hagl, C.; Grefen, L. New perspectives in patient education for cardiac surgery using 3D-printing and virtual reality. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1092007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargul, M.; Skorka, P.; Gutowski, P.; Kazimierczak, A.; Rynio, P. Empowering EVAR: revolutionizing patient understanding and qualification with 3D Printing. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, Y, Park, S. J.; Kim, T.; Kim, N.; Yang, D.H.; kim, J.B. Pre-sewn multi-branched aortic graft and 3D-printing guidance for Crawford extent II or III thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 34, 816–822. [Google Scholar]

- Raffort, J.; Adam, C.; Carrier, M.; Ballaith, A.; Coscas, R. Jen-Baptise, E, et al. Artificial intelligence in abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, I.; Gupta, A.; Ihdayhid, A.; Sun, Z. Clinical applications of mixed reality and 3D printing in congenital heart disease. Biomolecules. 2022, 12, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Squelch, A.; Sun, Z. Investigation of the clinical value of four visualization modalities for congenital heart disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, A.; Pagan-Diaz, G.J.; Grant, L.; Cvetkovic, C.; Bramlet, M.; Vozenilek, J.; Kesavadas, T.; Bashir, R. 3D printing for preoperative planning and surgical training. A review. Biomed. Microdevices. 2018, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).