1. Introduction

Given the importance of MRI as a routine diagnostic tool in many clinical pathways, the likelihood of needing a scan at some point in a lifetime is high. This finding holds even for cochlear implant recipients (van de Heyning et al., 2021).

Developments of the CI magnet to bipolar diametral magnets, which align to the applied magnetic field, allow a painless procedure without complications (Todt et al., 2017). The position of the implant at the head (Todt et al., 2015), the position of the head inside the MRI scanner (chin to chest) (Ay et al., 2021), and a proper sequence allow the routine assessment of the internal auditory canal and the cochlea.

These findings allow the routine follow-up of vestibular schwannoma and intralabyrinthine schwannoma in combination with a cochlear implant (Sudhoff et al., 2020; 2021). Further development and application of MARS sequences enable the reduction of artifacts around the implant and improved visualization of central structures (Edmonson et al., 2018; Canzi et al., 2023; Winchester et al., 2025).

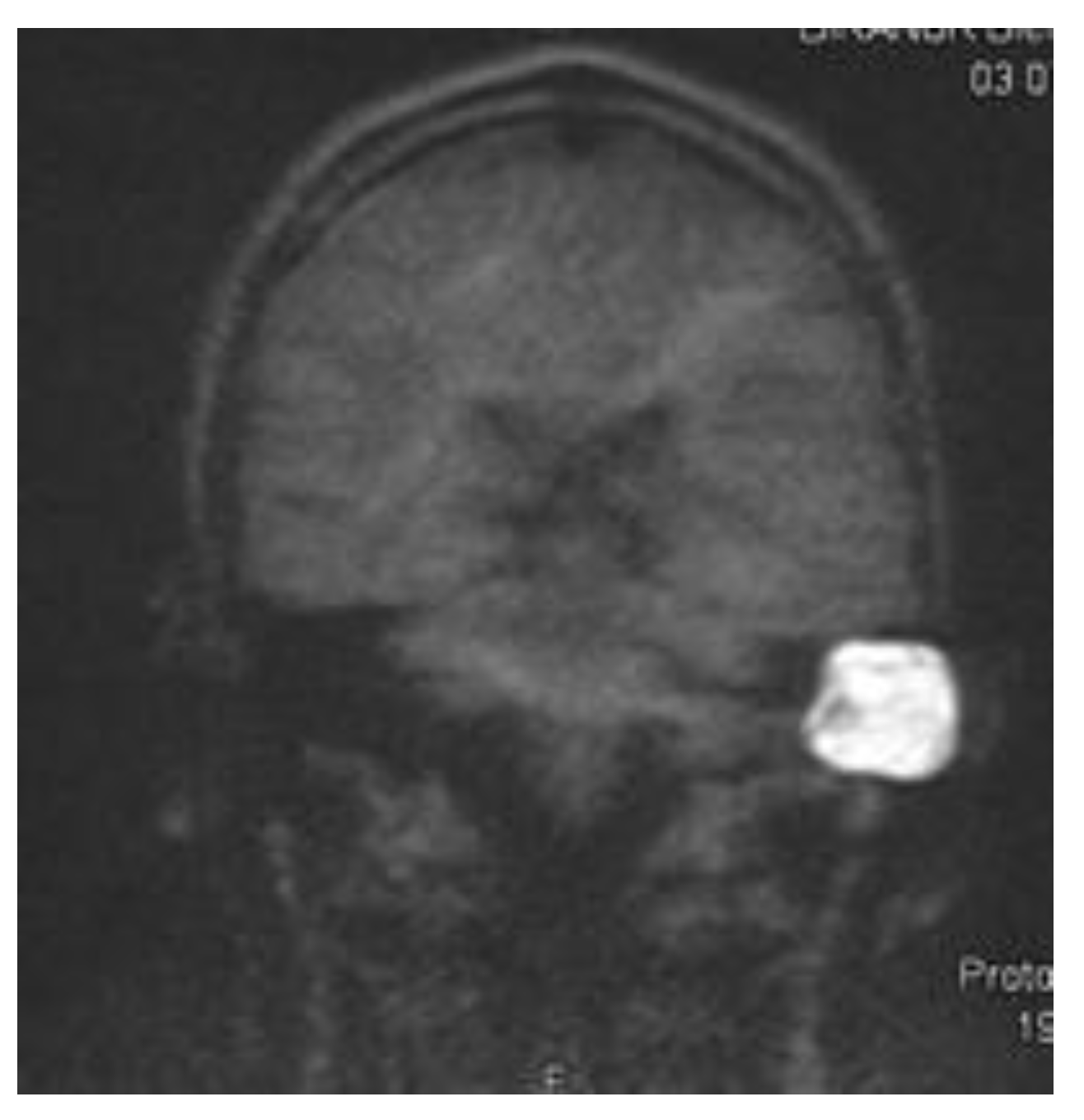

The introduction of MRI into the field of cholesteatoma detection allowed a non-surgical visual second look (Tran ban Huy et al., 1986) for the first time. Besides the initial single-shot echo planar imaging (EPI) DWI detection sequence (Fitzek et al., 2002), non-EPI echo planar imaging DWI was developed, achieving higher sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 97%, respectively (Jindal et al., 2011; De Foer et al., 2006). The disadvantage of most cholesteatoma detection sequences is their high susceptibility to magnetic fields. Therefore, significant distortive artifacts can be generated by an implant (Nassiri et al., 2024), which makes the evaluation of cholesteatoma impossible. Although modified cholesteatoma sequences, such as multishot EPI DWI RESOLVE and single-shot non-epi DWI HASTE (

Figure 1), are assumed to be less susceptible to magnets with acceptable rates of cholesteatoma detection (Bozer et al., 2024)

Subtotal petrosectomy (SP) contains the complete exenteration of pneumatized cells of the mastoid, removal of epithelialized cells, and removal of the posterior wall. Closure of the eustachian tube and a blind sac closure of the EAC is performed after filling the cavity with fat. This technique, developed in the late 1950s (Rambo et al., 1958), was combined with a cochlear implant in the late 1990s (Bendet et al., 1998) as a surgical solution for many pathologies. It is described as being performed in cases of COM, cholesteatoma, temporal bone fractures, otosclerosis, vestibular schwannomas, and inner ear malformations, in combination with a cochlear implant (Morelli et al., 2025). Related to the assumed good safety profile, the SP is widely used. Caused by the closure of the blind sac, a follow-up of the underlying etiological disease is based on clinical observation, and usually involves a CT scan. Since CT is not the radiological tool of choice for detecting cholesteatoma, knowledge about residual or recurrent cholesteatoma is primarily based on clinical observation and is therefore limited. Different authors have described the rate of cholesteatoma in the groups of PS and CI as ranging from 9.3% to 20% (Yan et al., 2020; Aristigue et al., 2022; Gray et al., 1999). It can be assumed that the rate of undetected cholesteatoma is different. Recently, Macielak et al. described the rate of cholesteatoma in patients with recurrent disease after surgery (SP) as 80%.

This study aimed to develop a procedure for detecting cholesteatomas in patients with cochlear implants using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

2. Method

We performed MRI scans on five volunteers with a cochlear implant (Synchrony 2, MED-EL, Innsbruck, Austria). The implants were fixed with a swimming cap at a 120° angle from the nasion to the external ear canal line, with a distance of 12 cm. Inside the scanner, the volunteers were advised to scan in a chin-to-chest (anteversion) position (Ay et al., 2021). A cushion supported the head.

1.5 T scanning was performed with a MAGNETOM Altea scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The performed sequences included a non-EPI HASTE DWI (t2_haste_diff_cor_p2).

3T scanning was performed using a MAGNETOM Skyra scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The performed sequences were a RESOLVE DWI (resolve_4scan_trace_tra_p2_192) and an EPI Sequence (ep2d_diff_4scan_trace_p2). For both scanners, a 20-channel head coil was used.

SAR values were calculated for each sequence. Related to the sequence installed on the different scanners, sequences could not be performed in all scanners.

The ethical board of the Westfälische Wilhelms Universität (2019, 135 fS, 20.08.2019) gave their approval for the study.

3. Results:

3.1. EP2D-Diff-Sequence

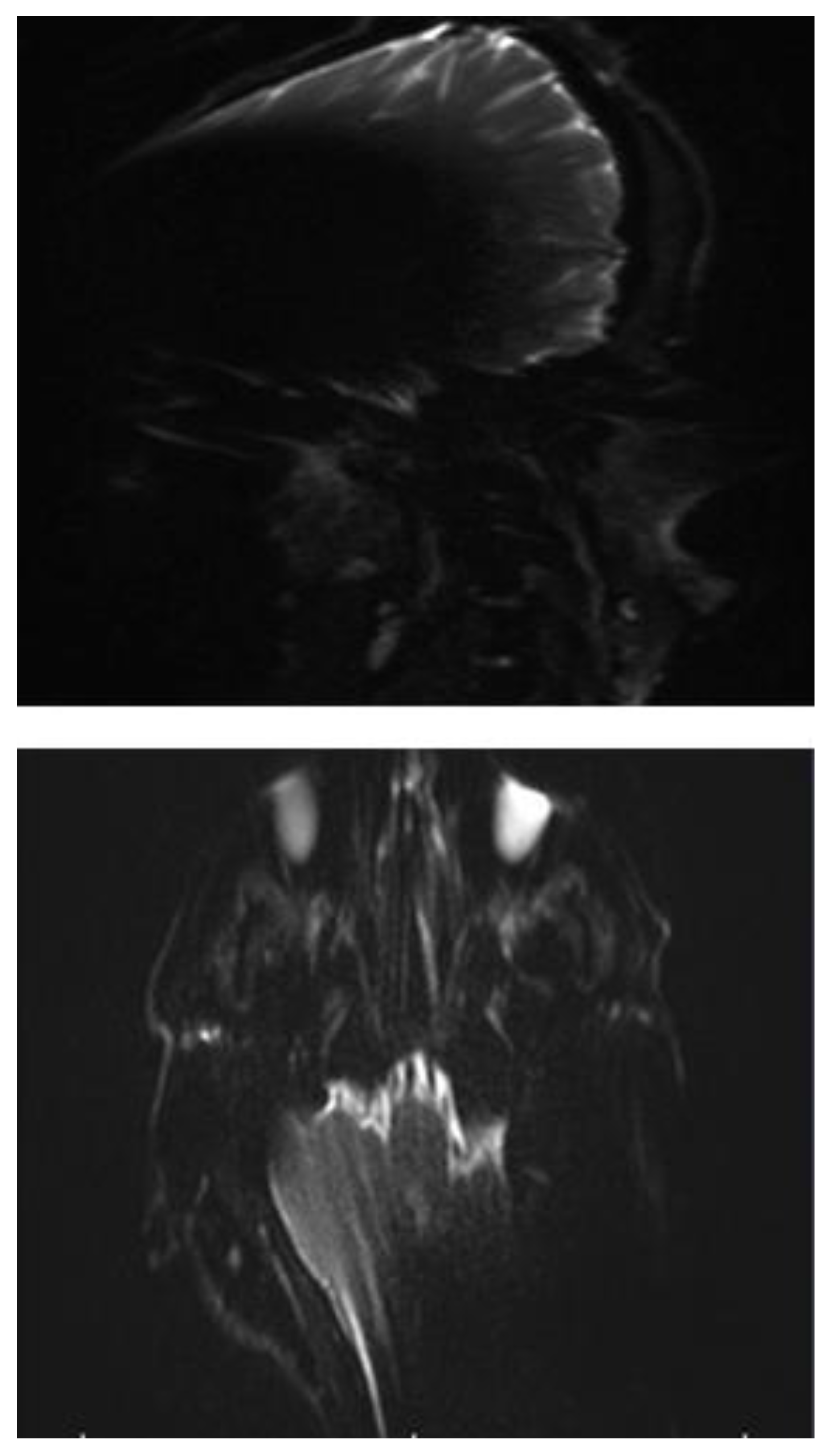

In all three subjects, the EP2D diffusion sequence shows a pronounced susceptibility artifact in both the axial and coronal planes with areal signal loss and, in some cases, considerable geometric distortions. Around the cochlear implant, central, hypointense signal losses with hyperintense fringes are impressive, whereby these fringe phenomena appear particularly pronounced in the coronal plane.

Due to the pronounced stretching and distortion effects, anatomically correct visualization of the mastoid cavities, the external auditory canal, and the internal auditory canal is considerably impaired on both sides. (

Figure 2a,b).

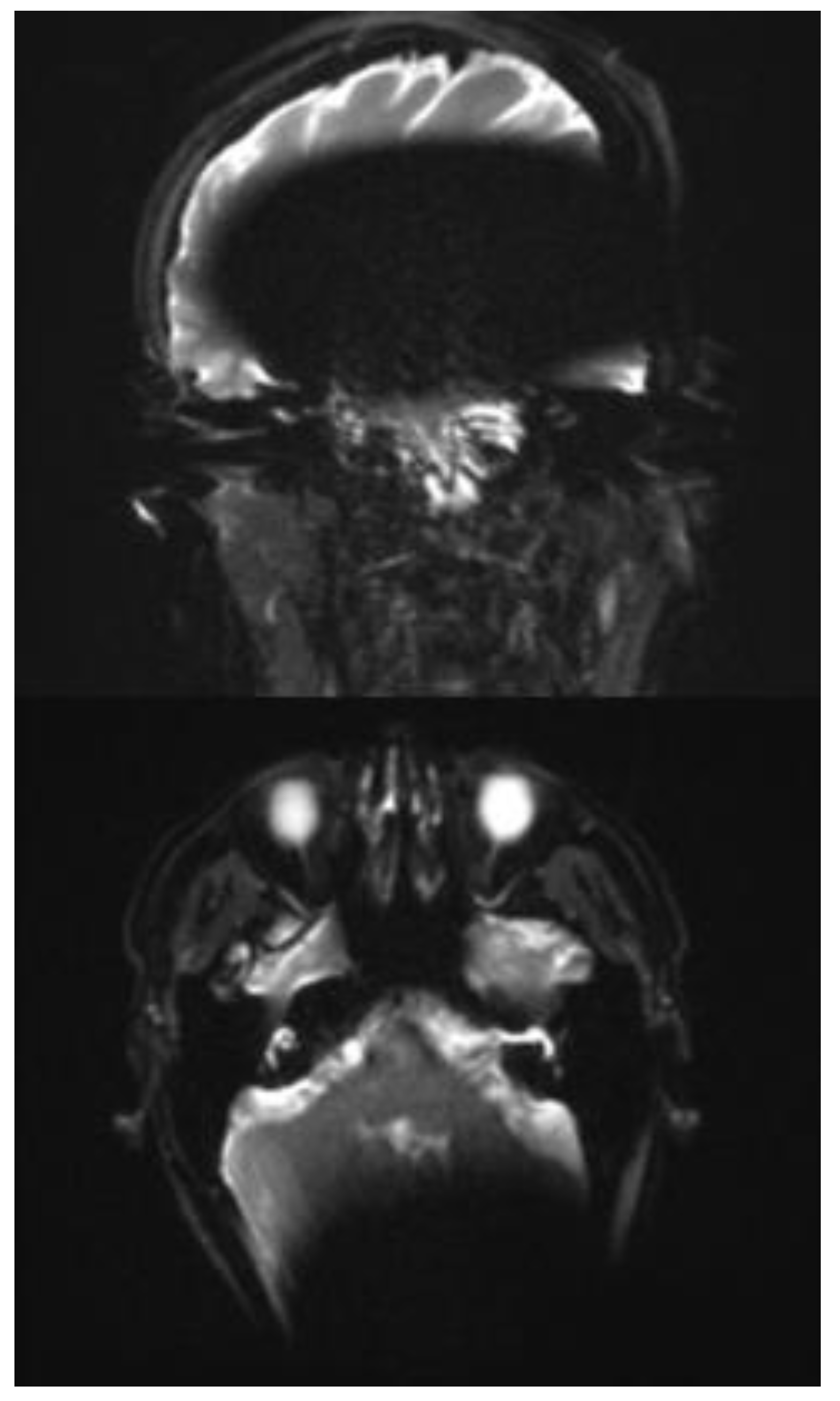

3.2. RESOLVE Sequence

In the transverse as well as in the coronal image plane, a localized signal loss in the region of the cochlear implant can be seen, corresponding to a pronounced metal-induced susceptibility artifact. The average artifact extension in the axial orientation is 108 mm (subject 1: 103 mm; subject 2: 106 mm; subject 3: 116 mm), while in the coronal plane, it is 146 mm (subject 1: 156 mm; subject 2: 147 mm; subject 3: 134 mm). In the coronal image, a disproportionate craniocaudal and mediolateral artifact extension is also impressive, which extends beyond the temporal lobe to the midline and projects into deeper contralateral brain sections.

In each case, the artifacts are accompanied by geometric distortions as well as grid- or band-like signal inhomogeneities in the peripheral area.

In all three cases examined, the ipsilateral mastoid air cell can be visualized mainly in both planes. In subjects 2 and 3, however, the distal section of the ipsilateral mastoid exhibits a partial artifact overlay, which limits assessment. The contralateral mastoid cavity can be assessed in its full extent in all subjects without restrictions.

In the axial plane, both the ipsilateral cochlea and the internal auditory canal remain unaffected by the artifact spread. The course of the internal auditory canal can be visualized artifact-free up to the cerebellopontine angle and assessed without any discernible geometric distortions. In the coronal view, however, complete traceability of these structures is not reliably possible due to superimposed artifacts. The same applies to the visualization of the external auditory canal, which can only be assessed to a limited extent in the coronal plane due to artifacts. (

Figure 3a and b).

3.3. HASTE Sequence

In the HASTE sequence (1.5 Tesla), all three subjects exhibited a signal extinction localized around the cochlear implant, consistent with a metal-induced susceptibility artifact. This is localized ipsilaterally, temporoparietally, and occipitally, and manifests as a centrally hypointense area. The mean extent of the artifact in axial orientation is 60 mm (subject 3: 61 mm; subject 4: 48 mm; subject 5: 71 mm). In the coronal plane, the average extension is 102 mm (test subject 3: 128 mm; test subject 4: 125 mm; test subject 5: 54 mm). In cases 3 and 4, the artifact extension in the coronal plane extends beyond the midline. A relevant geometric distortion of the surrounding structures is not recognizable in any of the cases. Minor, unspecific signal inhomogeneities can be seen at the edges of the artifact zones. Due to the image quality, the anatomical detail recognizability is limited in all three subjects.

In subjects 3, 4 and 5 both the ipsilateral and the contralateral mastoid can be displayed completely and without artifact overlay. The same applies to the internal and external auditory canals, which are imaged artifact-free on both sides. (

Figure 4a and b)

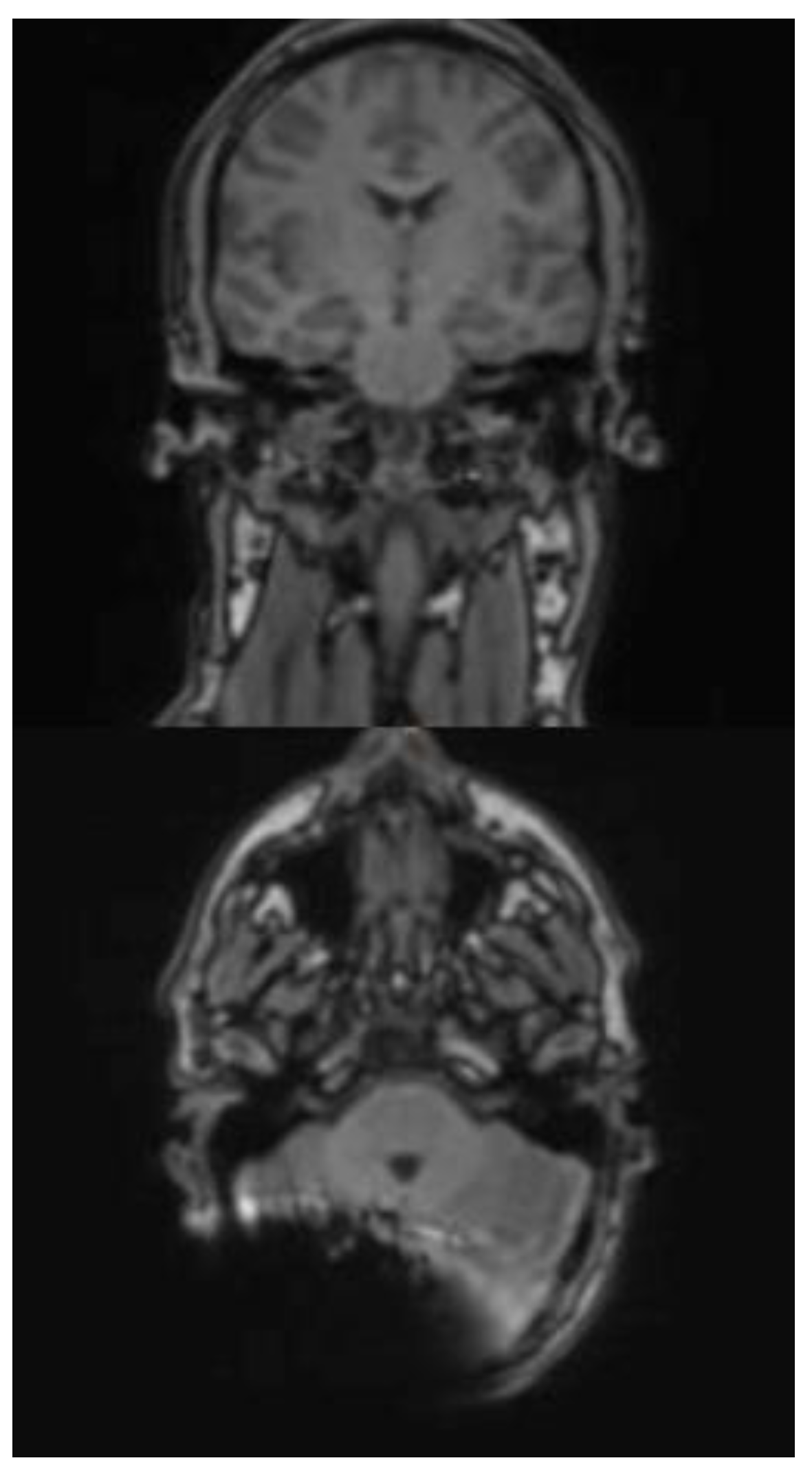

The effect of a closer position of the implant to the EAC and a non-anteverted head position inside the scanner is shown in

Figure 5a and b. Here, the ipsilateral mastoid and internal auditory canal (IAC) are not assessable.

SAR values calculated for all used sequences and scanners were between 0.18 and 0.36 (W/kg)

3.4. Discussion

Cholesteatoma assessment by MRI scanning has become a routine procedure in many otologic departments, as it offers an option for a non-surgical second look after cholesteatoma surgery. A high rate of sensitivity and specificity made it a reliable tool (Bozer et al., 2024).

A significant disadvantage of the commonly used epi and non-epi sequences in DWI is susceptibility to magnetic fields and the generation of distortional artifacts (Nassiri et al., 2024). This has, so far, made radiological cholesteatoma follow-up in cochlear implant recipients impossible. Therefore, the follow-up in cases of subtotal petrocectomy relied on clinical observation and CT scans (Morelli et al., 2025). Despite this limitation, the rate of cholesteatoma in this group is described to be between 9.3% and 20% (Yan et al., 2020; Aristigue et al., 2022; Gray et al., 1999).

Subtotal petrosectomy is a reliable surgical technique in cases of COM, Cholesteatoma, temporal bone fractures, otosclerosis, vestibular schwannomas, and inner ear malformations, including a blind sac closure, which makes a visual microscopic observation impossible. Recent publications have reported high rates of recurrent cholesteatoma in patients without cochlear implants after 8 years (Macielak et al., 2023). The magnetic artifact of the cochlear implant currently makes radiological cholesteatoma follow-up by MRI impossible.

Our findings enable a radiologic assessment of the mastoid with a cochlear implant in place, thereby resolving this issue. The use of RESOLVE or HASTE sequences for cholesteatoma detection makes it possible to assess the mastoid region for the first time. However, it is worth noting that not only is the used sequence important. Additionally, the implant must be placed 12 cm behind the external auditory canal (EAC), and the patient’s head must be positioned inside the MRI scanner in a chin-to-chest position (Ay et al., 2021). (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The importance of not solely focusing on the used sequence becomes clear when examining

Figure 5. In this case. However, a proper sequence was used, but a visualization of the mastoid region was not possible because the implant position and head position were not as advised.

This proposed guideline needs to be tested in vivo now. Although the HASTE sequence is available at 3 T, we were unable to test it since it was not installed at the time of observation.

Although it has been shown that hair cells’ function (residual hearing) is not affected by MRI scanning in cochlear implant recipients (Eichler et al., 2023), specific SAR values are of high importance. The SAR values in our observations, ranging from 0.18 to 0.36 W/kg, were all within the manufacturer’s given limitations: 3.2 W/kg for head MRI (1.5T) and 1.6 W/kg for head MRI at 3T (MEDEL, Innsbruck, Austria). Therefore, all scans could be performed even in vivo without any risk to the patient.

4. Conclusion

Postoperative cholesteatoma assessment after CI implantation and subtotal petrosectomy appears to be possible under 1.5 T and 3 T, considering the MRI sequence, implant position, and head position.

Acknowledgement

MEDEL: Innsbruck, Austria supported this study.

References

- van de Heyning P, Mertens G, Topsakal V, de Brito R, Wimmer W, Caversaccio MD, Dazert S, Volkenstein S, Zernotti M, Parnes LS, Staecker H, Bruce IA, Rajan G, Atlas M, Friedland P, Skarzynski PH, Sugarova S, Kuzovkov V, Hagr A, Mlynski R, Schmutzhard J, Usami SI, Lassaletta L, Gavilán J, Godey B, Raine CH, Hagen R, Sprinzl GM, Brown K, Baumgartner WD, Karltorp E. Two-phase survey on the frequency of use and safety of MRI for hearing implant recipients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Nov;278(11):4225-4233. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Todt I, Rademacher G, Mittmann P, Wagner J, Mutze S, Ernst A. MRI Artifacts and Cochlear Implant Positioning at 3 T In Vivo. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. Juli 2015;36(6):972–6.

- Todt I, Tittel A, Ernst A, Mittmann P, Mutze S. Pain Free 3 T MRI Scans in Cochlear Implantees. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. Dezember 2017;38(10):e401–4.

- Ay N, Gehl HB, Sudhoff H, Todt I. Effect of head position on cochlear implant MRI artifact. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Off J Eur Fed Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Soc EUFOS Affil Ger Soc Oto-Rhino-Laryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2021;278(8):2763–7.

- Sudhoff H, Gehl HB, Scholtz LU, Todt I. MRI observation after intralabyrinthine and vestibular schwannoma resection and cochlear implantation. Front Neurol 2020;11:759.

- Sudhoff H, Scholtz LU, Gehl HB, Todt I. Quality Control after Intracochlear Intralabyrinthine Schwannoma Resection and Cochlear Implantation. Brain Sci. 2021 Sep 16;11(9):1221. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Canzi P, Carlotto E, Simoncelli A, Lafe E, Scribante A, Minervini D, Nardo M, Malpede S, Chiapparini L, Benazzo M. The usefulness of the O-MAR algorithm in MRI skull base assessment to manage cochlear implant-related artifacts. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2023 Aug;43(4):273-282. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edmonson HA, Carlson ML, Patton AC, Watson RE. MR imaging and cochlear implants with retained internal magnets: reducing artifacts near highly inhomogeneous magnetic fields. Radiographics 2018;38:94 106.

- Winchester A, Cottrell J, Kay-Rivest E, Friedmann D, McMenomey S, Thomas Roland J Jr, Bruno M, Hagiwara M, Moonis G, Jethanamest D. Image Quality Improvement in MRI of Cochlear Implants and Auditory Brainstem Implants After Metal Artifact Reduction Techniques. Otol Neurotol. 2025 May 1. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran Ba Huy P, Lévy C, Bensimon JL, Cophignon J. Cinq cas de kyste épidermoïde (ou cholestéatome primitif) de la pyramide pétreuse.Aspects clinique, radiologique, pathogénique et thérapeutique. Intérêt de la RMN dans la diagnostic et la surveillance post-operatoire [5 cases of epidermoid cyst (or primary cholesteatoma) of the petrous pyramid. Clinical, radiologic, pathogenic and therapeutic aspects. Value of nuclear magnetic resonance in the diagnosis and postoperative monitoring]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1986;103(6):363-71. French. [PubMed]

- Jindal M, Riskalla A, Jiang D, Connor S, O’Connor AF. A systematic review of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of postoperative cholesteatoma. Otol Neurotol. 2011 Oct;32(8):1243-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Foer B, Vercruysse JP, Pilet B, Michiels J, Vertriest R, Pouillon M, Somers T, Casselman JW, Offeciers E. Single-shot, turbo spin-echo, diffusion-weighted imaging versus spin-echo-planar, diffusion-weighted imaging in the detection of acquired middle ear cholesteatoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Aug;27(7):1480-2. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fitzek C, Mewes T, Fitzek S, Mentzel HJ, Hunsche S, Stoeter P. Diffusion-weighted MRI of cholesteatomas of the petrous bone. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Jun;15(6):636-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozer A, Adıbelli ZH, Yener Y, Dalgıç A. Diagnostic performance of multishot echo-planar imaging (RESOLVE) and non-echo-planar imaging (HASTE) diffusion-weighted imaging in cholesteatoma with an emphasis on signal intensity ratio measurement. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2024 Nov 6;30(6):370-377. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rambo JH. Primary closure of the radical mastoidectomy wound: a technique to eliminate postoperative care. Laryngoscope,1958; 68(7):1216-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendet E, Cerenko D, Linder TE, Fisch U. Cochlear implantation after subtotal petrosectomies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol,1998; 255(4):169–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arístegui I, Aranguez G, Casqueiro JC, Gutiérrez-Triguero M, Pozo AD, Arístegui M. Subtotal Petrosectomy (SP) in Cochlear Implantation (CI): A Report of 92 Cases. Audiol Res. 2022 Feb 25;12(2):113-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gray F, Ray J, McFerran J, Further experience with fat graft obliteration of mastoid cavities for cochlear. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, October 1999, Vol. 113, pp. 881-884.

- Yan F, Reddy PD, Isaac MJ, Nguyen SA, McRackan TR, Meyer TA. Subtotal Petrosectomy and Cochlear Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Oct 15;147(1):1–12. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macielak RJ, Kull AJ, Carlson ML, Patel NS. Disease recidivism after subtotal petrosectomy and ear canal closure. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023 Mar-Apr;44(2):103743. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler T, Ibrahim A, Riemann C, Scholtz LU, Gehl HB, Goon P, Sudhoff H, Todt I. Prospective Evaluation of 3 T MRI Effect on Residual Hearing Function of Cochlea Implantees. Brain Sci. 2022 Oct 19;12(10):1406. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).