1. Introduction

Cholesteatoma is a non-malignant growing accumulation of squamous epithelium in the middle ear. A cholesteatoma can lead to the destruction of the ossicular chain and the adjacent parts of the temporal bone as well as the skull base [

1]. Related destructions and the accompanying infection can cause progressive hearing loss and brain abscesses [

2,

3].

Surgery is the treatment of choice and can induce further destruction. Surgical main goal is the complete removal of the cholesteatoma [

4]. Secondary goals of the operation are to restore sound transmission and the skull base, if affected [

5].

In addition to autologous materials such as cartilage, foreign materials such as hydroxyapatite cement, gold or titanium can likewise be used for reconstruction [

6]. Titanium foreign materials (prostheses, meshes) are currently used most frequently [

5,

7].

Follow-up examinations are needed to detect residual cholesteatoma and recurrences after surgery. This can be done by means of second-look surgery or a magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) examination with a non-echo planar imaging diffusion weighted (non-EPI DWI) sequence [

8,

9].

Implants, like ossicular prothesis, made of titanium or other metals cause an artifact in MRI [

10]. The enlargement of the artifact is dependent on the chosen material, the form, and the size of the implant.

The evaluation of the limitation of cholesteatoma detection by non-EPI DWI sequence-generated MRI artifacts due to titanium foreign material (prosthesis, mesh) is of major relevance, which has been neglected so far.

This study is aimed to estimate non-EPI DWI sequence-generated MRI artifact size of titanium foreign material to get insights in a possible role for cholesteatoma detection.

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study we screened all patients who underwent a tympanoplasty with resection of a cholesteatoma in our tertiary university hospital between 2020 to 2023. To be included in the study, a partial ossicular replacement prosthesis (PORP), a total ossicular replacement prosthesis (TORP) or a titanium mesh had to be implanted during surgery.

In addition, an MRI with non-EPI-DWI sequence had to be performed after the implantation.

Furthermore, a second operation had to be performed based on the MRI results or the clinical findings. The reasons for the second operation were a suspected cholesteatoma on MRI or the clinical findings, a prosthesis protrusion, or an increasing air-bone gap.

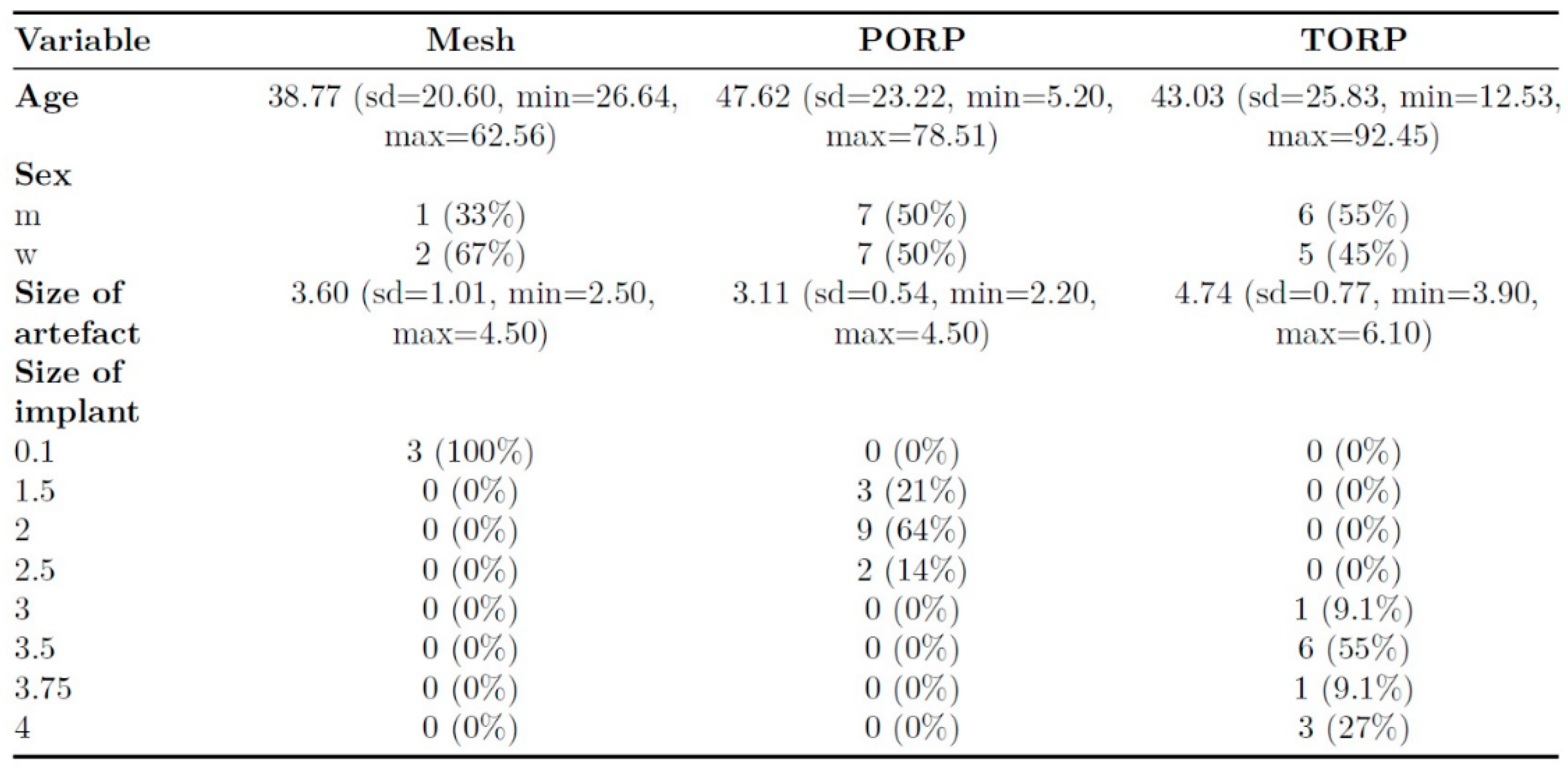

550 cases were screened. Altogether 27 patients and 28 MRI examinations were included. The mean age of the patients at the time of the MRI was 44,9 years and the median age was 51,4 years. The sizes of the PORP and TORP varied between the patients and the thickness of the titanium mesh was 0,1 mm.

This study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ärztekammer Westfalen- Lippe, University of Münster Faculty of Medicine, Bielefeld University, Medical Faculty- Reference: 2022-314-f-S).

In all cases the scans were performed in a 1,5 T MRI system (Achieva, Philips, Best, The Netherlands). The imaging protocol consisted of a T1-, a T2-, an isoDWI- and a non-EPI DWI sequence.

The parameters for the T1- sequence were time of repetition (TR) 550 ms, time of echo (TE) 10 ms, matrix size (MS) 256 x 256, field-of-view (FOV) 100 mm, slice thickness (ST) 3 mm; for the T2-sequence TR 5058,58 ms, TE 100 ms, MS 512 x 512, FOV 80,21 mm, ST 5 mm; for Non Epi DWI-sequence TR 4134,25 ms, TE 73,67 ms, MS 288 x 288, FOV 104,17 mm, ST 5 mm, B 1000 s/mm³; for TR 11726,62 ms, TE 205,65 ms, MS 128 x 128, FOV 100 mm, ST 3 mm, B 1000 s/mm³.

The artifact caused by the implanted prosthesis or meshes was depicted and measured in T1- respectively T2-Sequence and for the titanium meshes also in the non-EPI DWI sequence. The measured artifacts were correlated with the known size of the prosthesis and meshes.

The scans were screened for cholesteatoma. The screening results were compared to the findings of the second performed surgery.

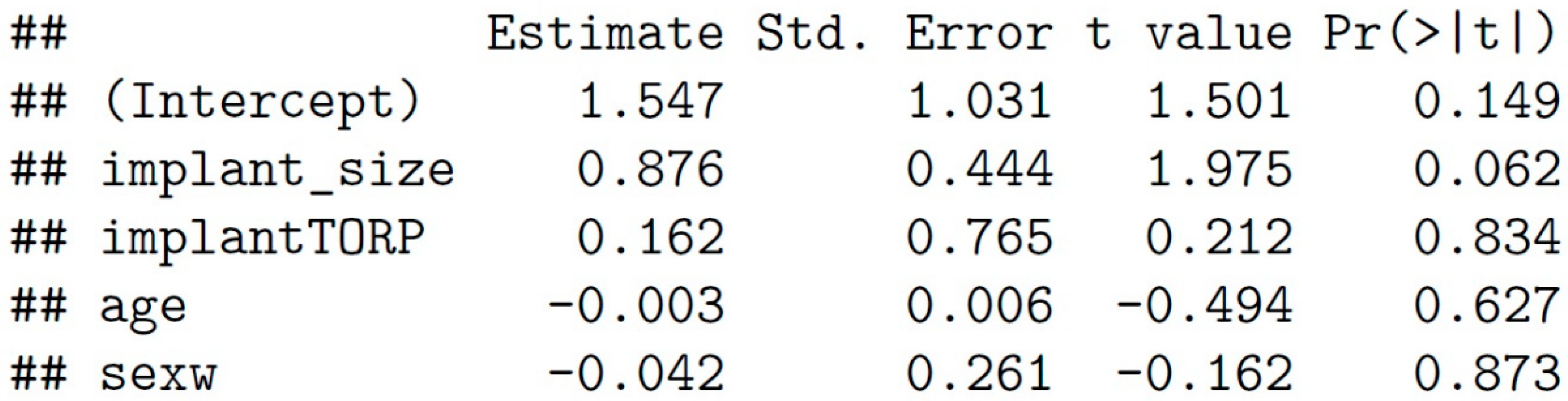

The analysis was performed in R (RStudio Team) based on Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft, Redmond, USA). A comparison between the MRI result and the findings of the second surgery was performed. A linear regression analysis was performed to assess the impact of the size and type of implant on the final artifact size. The regression was adjusted to age and sex.

3. Results

During the first operation a PORP was implanted in 14 cases, a TORP in 11 cases and a mesh in 3 cases. The sizes of the PORPs and TORPs varied between 3 respectively 4 different sizes (see

Table 1). All meshes had a thickness of 0,1 mm.

The time between the operation and the MRI amount to 619 d on average.

In 17 cases the MRI showed a cholesteatoma in the non-EPI DWI sequence. In 11 cases, no cholesteatoma was detected.

The second surgery confirmed the results of the MRI in 23 of 28 cases (82,1 %). The 5 not confirmed cases were false positive. The MRI indicated a cholesteatoma, but the surgery showed histopathological verified inflammatory and scar tissue. There were no false negative cases.

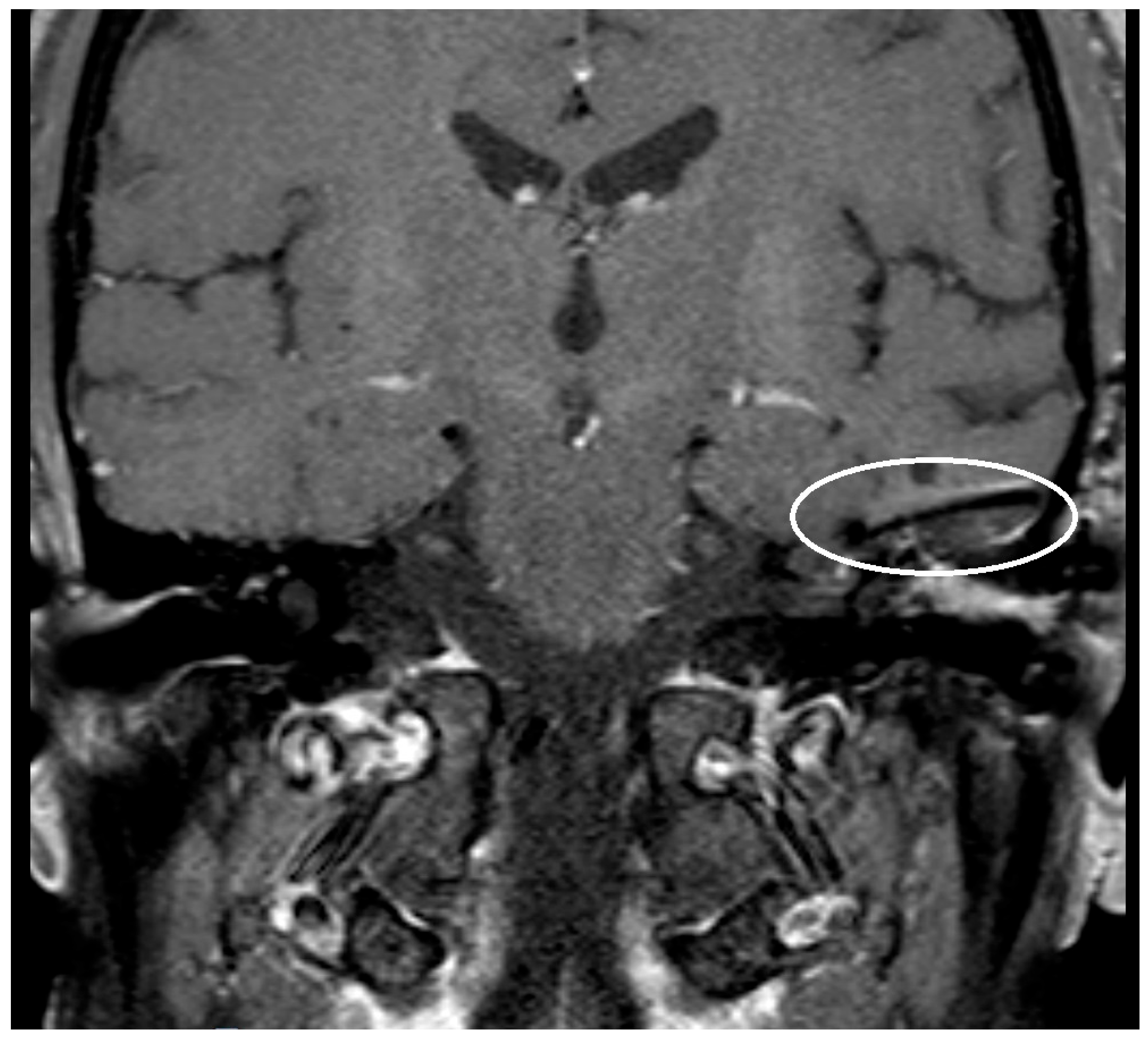

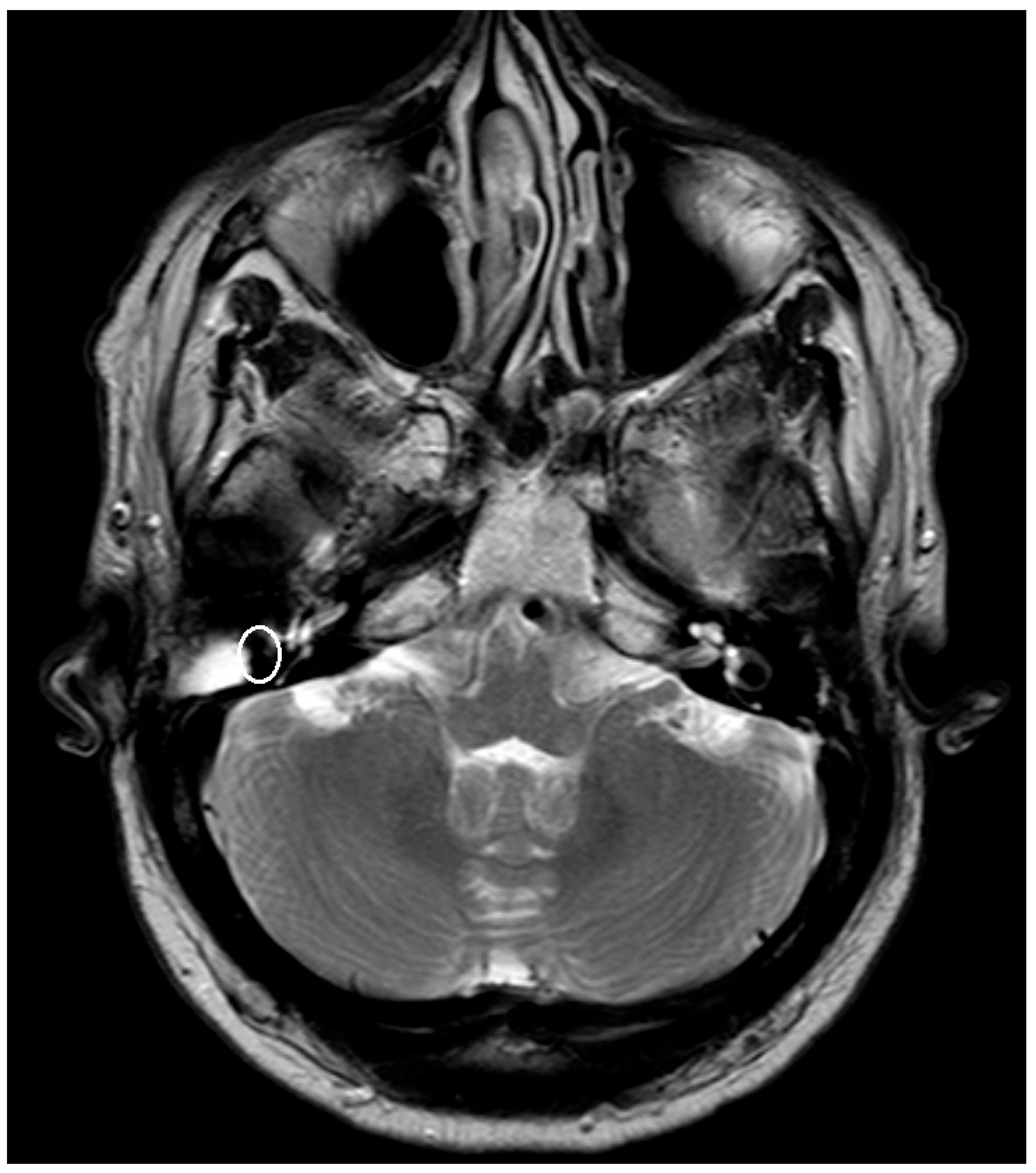

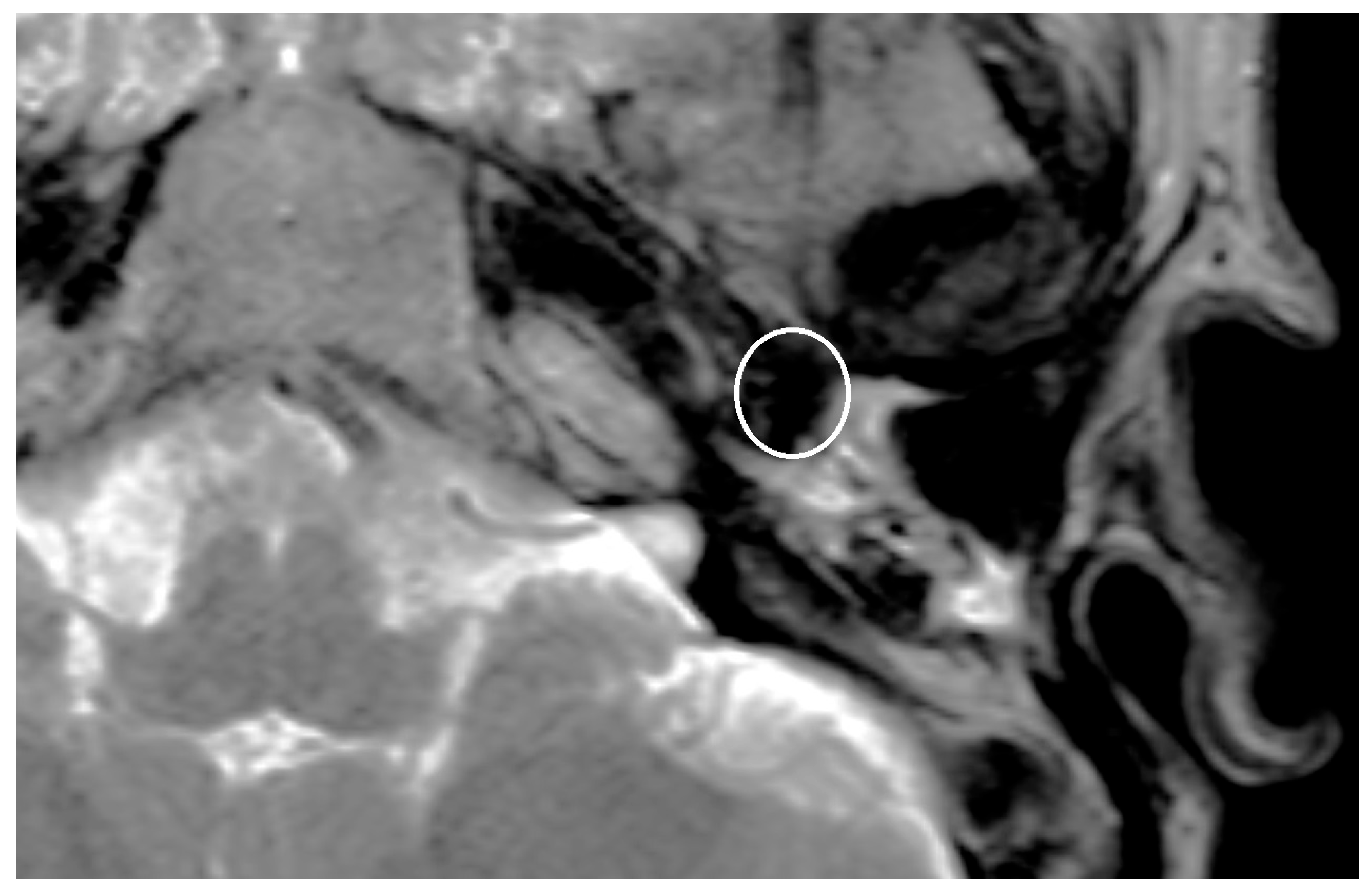

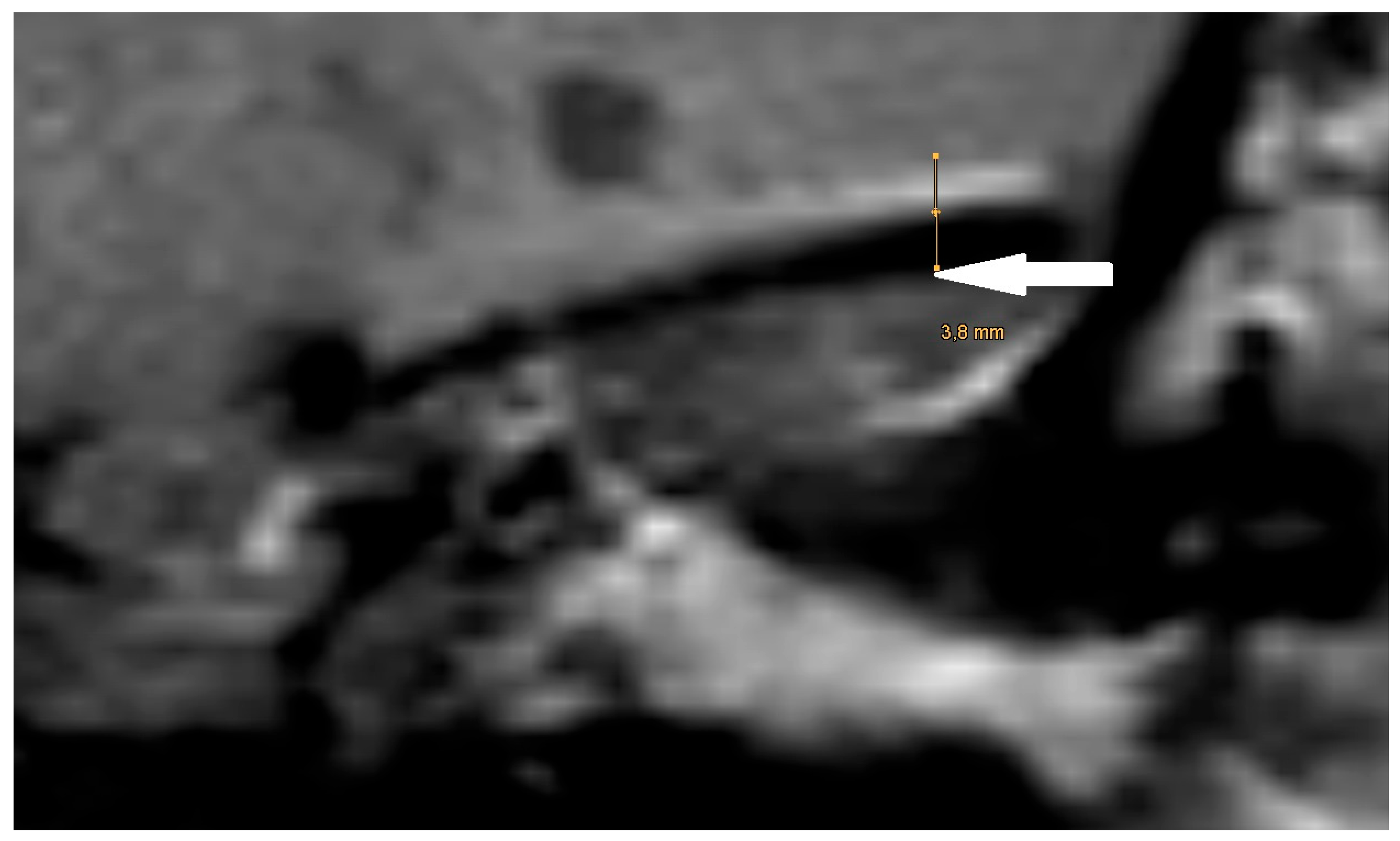

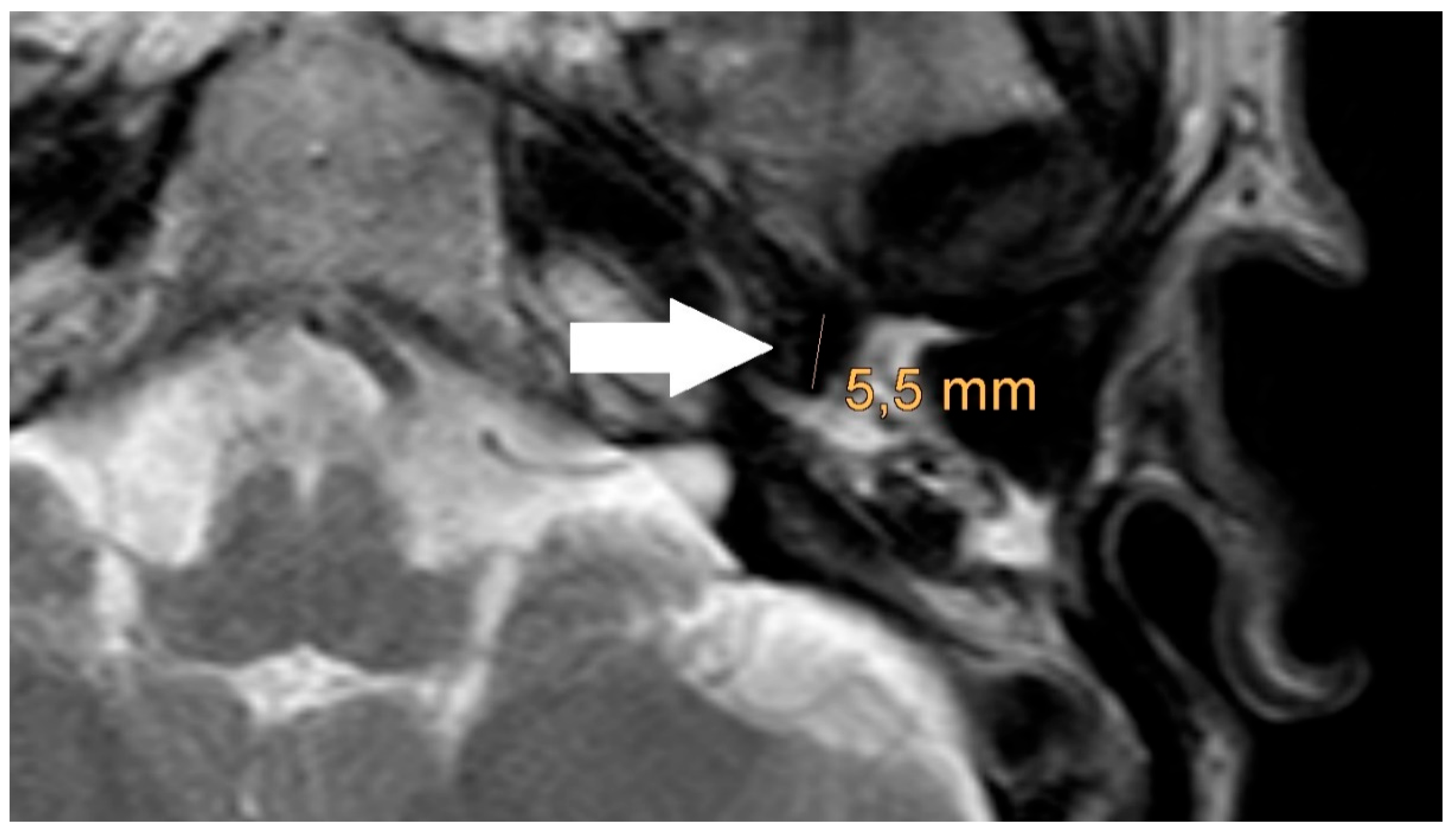

The artifact measurements firstly done in T1- or T2-sequence showed an average artifact of 3,1 mm for PORP, 4,7 mm for TORP and 3,6 mm for meshes (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The overall average artifact was 3,8 mm.

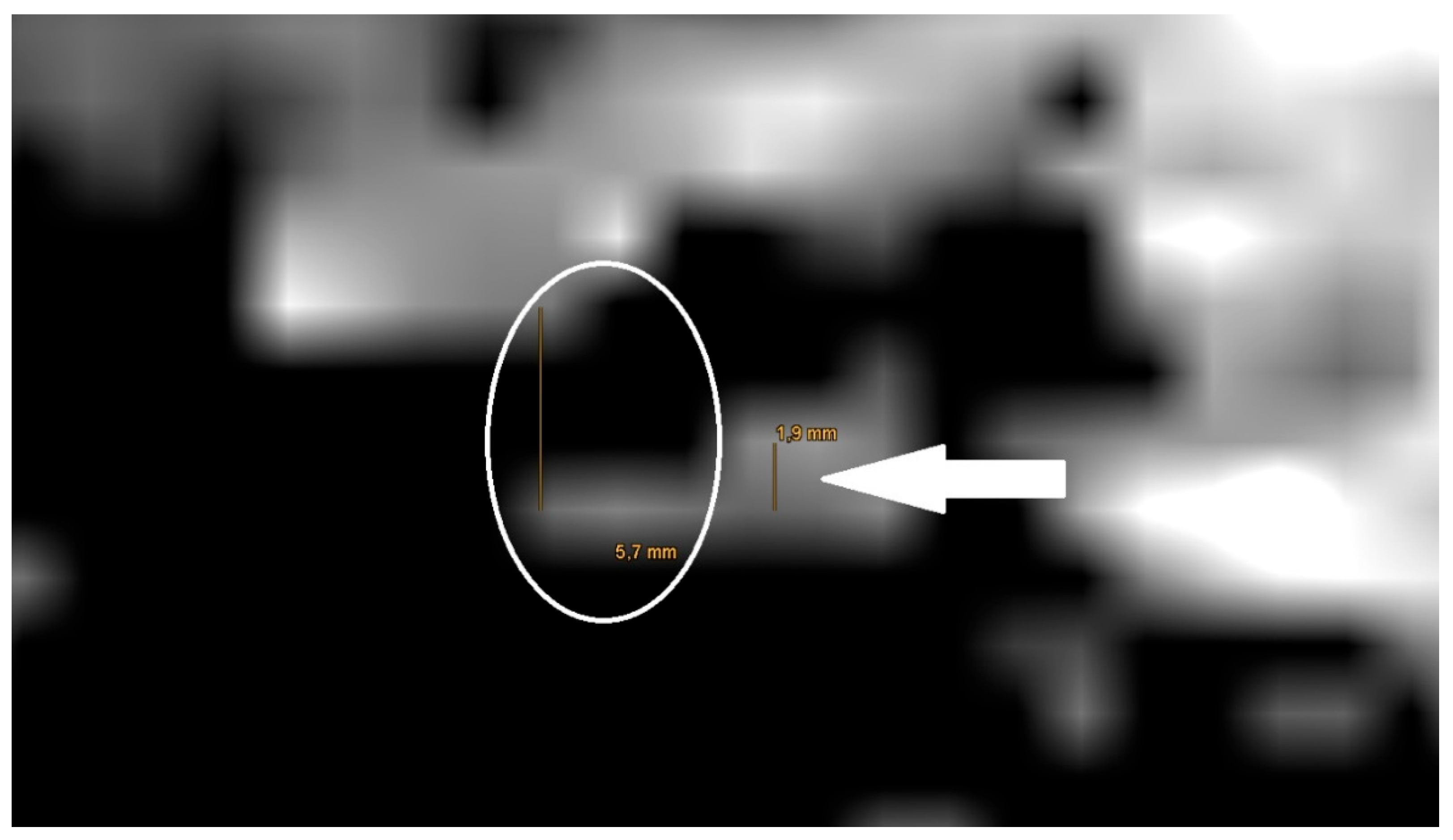

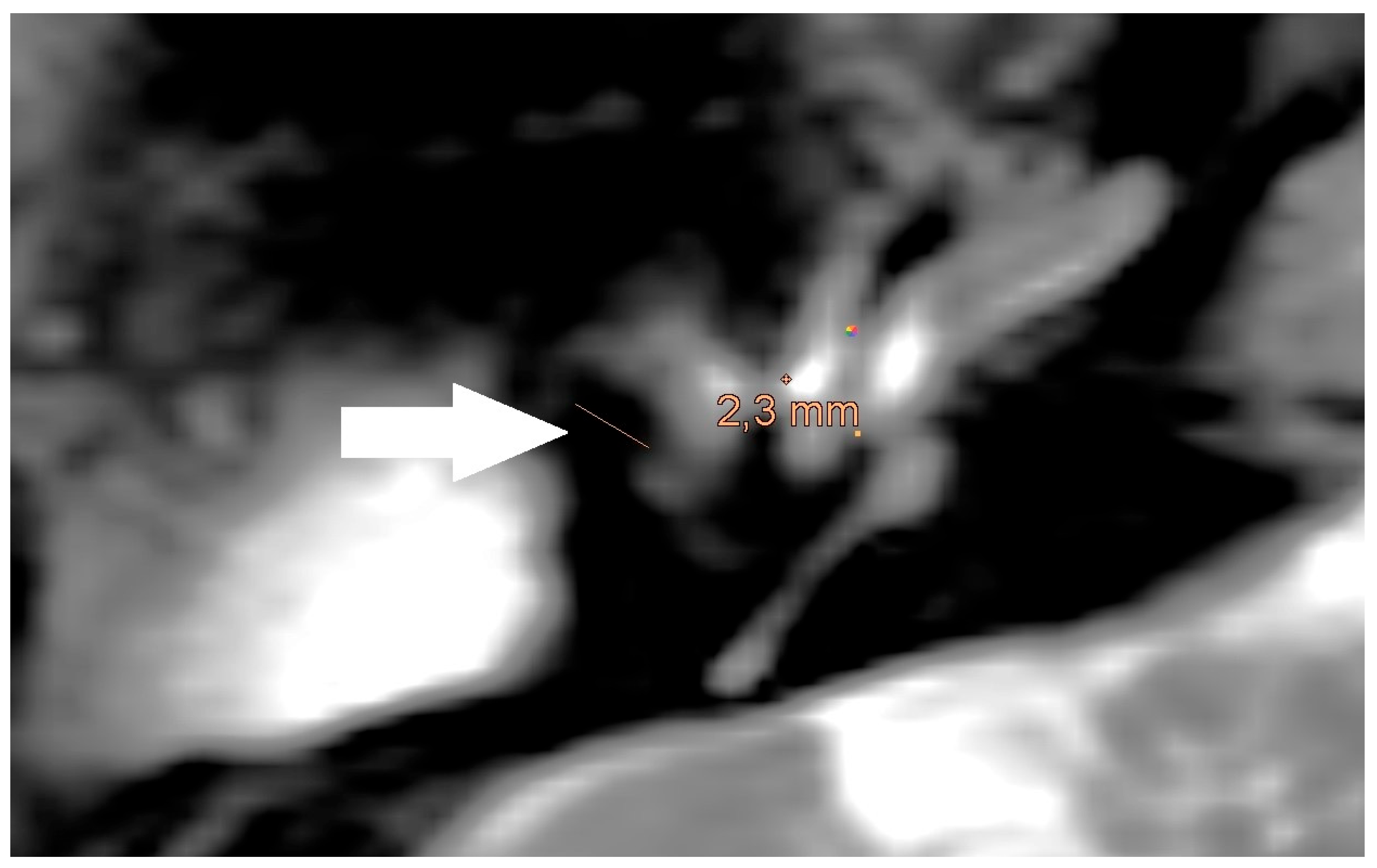

The also done measurement of the artifact for meshes in the non-EPI DWI sequence showed an average artifact size of 5,8 mm (see

Figure 3).

The measurement in the non-EPI DWI sequence revealed that the smallest edge length of the voxels in this sequence is 1,9 mm. Ensuing from this the smallest part that can be shown is one voxel (see

Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Magnification of the same artifact from

Figure 1c with measurement, see white arrow.

Figure 7.

Magnification of the same artifact from

Figure 1c with measurement, see white arrow.

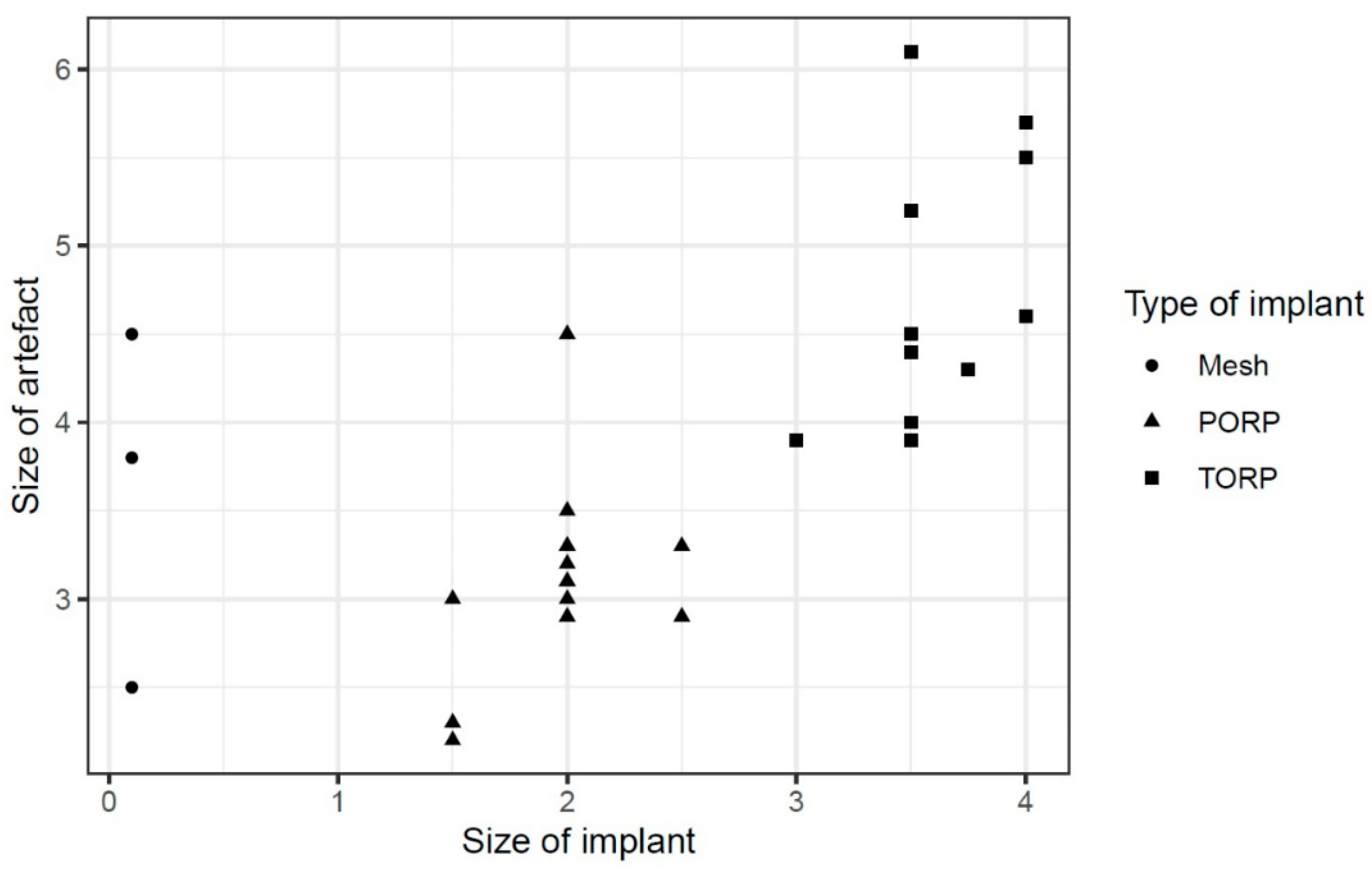

The regression showed that the implant size of PORP and TORP affects the artifact size positively by about 0.876 [95%-confidence interval (CI): -0.049; 1.802] (see

Diagram 1).

Other parameters such as age or gender of the patients showed insignificant influences [age: -0.003, 95%-CI: -0.015; 0.009, sex: -0.042, 95%-CI: -0.587; 0.503] (see

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Recurrence control in patients with cholesteatoma is of high importance [

11,

12,

13,

14]. There are different concepts of follow up for cholesteatoma control. While some clinics perform a second look in all cases other do not see the need for a second-look operation in all cases. A postoperative control with MRI with non-EPI DWI sequence is a possibility of control without the risk of another anesthesia and surgery [

15,

16].

MRI artifacts are an important topic in patients with metal implants. The form and enlargement of the artifact depends on the used metal and the size of the implant [

10].

The material used for all prothesis and meshes in our study was titanium. Our study shows that a larger size of the used prothesis leads to an increase of the artifact in MRI. This is similar to former studies [

17].

The MRI artifact also depends on the magnetic resonance (MR) scanner which is used for the examination and its magnetic field strength [

17]. In all examinations in this study, the same MR scanner was used.

Another impact on the artifact is the used MRI sequence. The local resolution varies between the different MRI sequences. A non-EPI DWI sequence has a higher detection rate for cholesteatoma than other MRI sequences [

14]. However, T1- and T2-sequences have a higher resolution than a non-EPI DWI sequence. The resolution of different MRI sequences has an impact on cholesteatoma detection [

18].

In our study the detection rate in the non-EPI DWI sequence (82.1%) was lower than in other studies. In these studies, a reconstruction with prostheses was not mentioned or ruled out [

15,

16,

19].

The detection rate of a cholesteatoma also depends on the presence of a prosthesis and the proximity of the cholesteatoma to the prosthesis. In our study, the prostheses cause artefacts of at least 2.2 mm in the T1-/T2 sequences. In the non-EPI DWI sequence, the voxel size is 1.9mm and larger than in T1-/T2 sequences. So, to detect a cholesteatoma the cholesteatoma must have a size of larger than 1.9 mm. A cholesteatoma smaller than 1.9 mm which is near to the prosthesis would be covered of the artifact of the prosthesis. Our findings are similar to former studies [

18].

There were false positive examination results in the MRI in our study but no false negative. Other studies show similar results. Thus false positive results can occur because of inflammation in the middle ear or cartilage grafts [

18,

20].

In former studies especially small cholesteatomas were found in second-look operations although the MRI showed no hint of a cholesteatoma [

13,

21]. This is similar to our assumptions for the non-EPI DWI sequence because of the limitations of the voxel size which is also similar to former studies [

18].

Our study's limitations are the small number of patients and the lack of artifact predictability.

A follow-up with MRI examinations should be considered to notice a growing cholesteatoma [

13,

21].

The thought of small cholesteatomas should be considered in the assessment of an ossicle reconstruction in single-staged or a later operation. The decision for a single-staged ossicle reconstruction in one operation with cholesteatoma excision leads to an effect on detection of a recurrent cholesteatoma and can be a reason for a second-look operation.

All in all, the detection of a cholesteatoma depends on several points. Foreign material, especially metal, used for reconstruction affects the size of the artifact in the MRI. The chosen MRI sequence also influences the artifact. The MRI sequence determines the size of the voxels in the depiction. The presumptive border of detection is around 2 mm.

Under these circumstances the size of the cholesteatoma influences the possibility of detection. A small cholesteatoma near to the implanted foreign material may not to be detected, while a large cholesteatoma can be detected. These considerations should be taken into account when deciding on immediate or delayed hearing reconstruction during ear surgery for cholesteatoma removal.

5. Conclusions

Artifacts associated with titanium material could affect the detectability of recurrent cholesteatoma on MRI. The detection border of a cholesteatoma is around two millimeters. A cholesteatoma smaller than this threshold could be missed. Single or two-stage reconstruction approaches after cholesteatoma surgery need to be discussed.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.P. and I.T.; methodology, C.J.P. and I.T.; validation, D. M., H.-B.G., L.-U.S., A.K., C.R. and D.V.; formal analysis, D.V.; investigation, C.J.P., D.M. and I.T.; resources, H.-B.G., L.-U.S. and I.T.; data curation, C.J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.P.; writing—review and editing, A.K., C.R.; visualization, C.J.P., D.M.; supervision, I.T.; project administration, H.-B.G., L.-U.S., I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Ärztekammer Westfalen- Lippe, University of Münster Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research, Bielefeld University Medical Faculty Ethics Committee (protocol code 2022-314-f-S, 6 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imagining |

| non-EPI DWI |

non-echo planar imaging diffusion weighted |

| PORP |

partial ossicular replacement prosthesis |

| TORP |

total ossicular replacement prosthesis |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| MR |

magnetic resonance |

References

- Aslıer, M.; Erdag, T.K.; Sarioglu, S.; Güneri, E.A.; Ikiz, A.O.; Uzun, E.; Özer, E. Analysis of histopathological aspects and bone destruction characteristics in acquired middle ear cholesteatoma of pediatric and adult patients. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 82, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, D.A.; Quaranta, N.; Baguley, D.M.; Hardy, D.G.; Chang, P. Staging and management of primary cerebellopontine cholesteatoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2002, 116, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucu, A.I.; Patrascu, R.E.; Cosman, M.; Costea, C.F.; Vonica, P.; Blaj, L.A.; Hartie, V.; Istrate, A.C.; Prutianu, I.; Boisteanu, O.; et al. Cerebellar Abscess Secondary to Cholesteatomatous Otomastoiditis-An Old Enemy in New Times. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesole, A.S.; Doyle, E.J.; Sarkovics, K.; Gharib, M.; Samy, R.N. Outcomes of Soft Versus Bony Canal Wall Reconstruction with Mastoid Obliteration. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, S.; Watters, C.; Winters, R. StatPearls: Tympanoplasty; Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Ascherman, J.A.; Foo, R.; Nanda, D.; Parisien, M. Reconstruction of cranial bone defects using a quick-setting hydroxyapatite cement and absorbable plates. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2008, 19, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boghani, Z.; Choudhry, O.J.; Schmidt, R.F.; Jyung, R.W.; Liu, J.K. Reconstruction of cranial base defects using the Medpor Titan implant: cranioplasty applications in acoustic neuroma surgery. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, A.; Covelli, E.; Confaloni, V.; Rossi-Espagnet, M.C.; Butera, G.; Barbara, M.; Bozzao, A. Role of non-echo-planar diffusion-weighted images in the identification of recurrent cholesteatoma of the temporal bone. Radiol. Med. 2020, 125, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz Zufiaurre, N.; Calvo-Imirizaldu, M.; Lorente-Piera, J.; Domínguez-Echávarri, P.; Fontova Porta, P.; Manrique, M.; Manrique-Huarte, R. Toward Improved Detection of Cholesteatoma Recidivism: Exploring the Role of Non-EPI-DWI MRI. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, P.; Waldeck, A.; Strutz, J. Wie verhalten sich metallhaltige Mittelohrimplantate in der Kernspintomographie? Laryngorhinootologie. 2003, 82, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senn, P.; Haeusler, R.; Panosetti, E.; Caversaccio, M. Petrous bone cholesteatoma removal with hearing preservation. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerckhoffs, K.G.P.; Kommer, M.B.J.; van Strien, T.H.L.; Visscher, S.J.A.; Bruijnzeel, H.; Smit, A.L.; Grolman, W. The disease recurrence rate after the canal wall up or canal wall down technique in adults. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond, S.L.; Stegeman, I.; Grolman, W.; Aarts, M.C.J. A Systematic Review of Non-Echo Planar Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detection of Primary and Postoperative Cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzaffar, J.; Metcalfe, C.; Colley, S.; Coulson, C. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for residual and recurrent cholesteatoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2017, 42, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosefof, E.; Yaniv, D.; Tzelnick, S.; Sokolov, M.; Ulanovski, D.; Raveh, E.; Kornreich, L.; Hilly, O. Post-operative MRI detection of residual cholesteatoma in pediatric patients - The yield of serial scans over a long follow-up. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 158, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoudi, H.; Levy, R.; Baudouin, R.; Couloigner, V.; Leboulanger, N.; Garabédian, E.-N.; Belhous, K.; Boddaert, N.; Denoyelle, F.; Simon, F. Performance of Non-EPI DW MRI for Pediatric Cholesteatoma Follow-Up. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peschke, E.; Ulloa, P.; Jansen, O.; Hoevener, J.-B. Metallische Implantate im MRT – Gefahren und Bildartefakte. Rofo 2021, 193, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baráth, K.; Huber, A.M.; Stämpfli, P.; Varga, Z.; Kollias, S. Neuroradiology of cholesteatomas. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudau, C.; Draper, A.; Gkagkanasiou, M.; Charles-Edwards, G.; Pai, I.; Connor, S. Cholesteatoma: multishot echo-planar vs non echo-planar diffusion-weighted MRI for the prediction of middle ear and mastoid cholesteatoma. BJR Open 2019, 1, 20180015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, H.; Lee-Warder, L.; Mentias, Y.; Arullendran, P. Cartilage grafts mimicking cholesteatoma recurrence on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: a case series. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2023, 137, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, M.; Riskalla, A.; Jiang, D.; Connor, S.; O'Connor, A.F. A systematic review of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of postoperative cholesteatoma. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).