1. Introduction

Animal models facilitate the investigation of genetic, environmental, and physiological variables within a controlled environment, making them an essential component in identifying critical mechanisms of lung injury and repair. The reproducibility and adaptability of these models across various experimental conditions enhance their utility in preclinical studies focused on validating potential pharmacological interventions.

An example of a well-established animal model is cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema. Mice subjected to prolonged smoke exposure consistently develop morphological changes characteristic of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including alveolar destruction, increased airspace enlargement, and persistent chronic inflammation [

1,

2,

3]. This model reproduces the progressive tissue remodeling and inflammatory milieu observed in COPD patients, enabling the analysis of pathogenic pathways and therapeutic targets. It can also be used to examine the effects of other toxic agents in enhancing smoke-induced lung injury. This approach was instrumental in demonstrating the synergistic relationship between cigarette smoke and LPS-induced lung injury, pointing to the increased risk of primary and secondary smoke exposure for the development of pulmonary infections and other inflammatory conditions [

4,

5].

In addition to their role in identifying pathogenetic mechanisms, animal models play an important role in the preclinical evaluation of drug candidates. The results obtained from animal studies can be used to determine dosages, possible side effects, and appropriate endpoints to assess the efficacy of these agents [

6,

7]. These studies can also identify potential biomarkers for detecting lung disease at an early stage, facilitating timely therapeutic intervention. Studies of elastase-induced emphysema have revealed significant increases in elastin-specific crosslinking amino acids, desmosine, and isodesmosine (DID) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, suggesting their use as a means of detecting pulmonary emphysema and monitoring the efficacy of therapeutic agents [

8,

9].

To further illustrate the critical role of animal models in facilitating a deeper understanding of various lung diseases, the current paper focuses on how these models may be utilized to identify critical mechanisms of pulmonary injury, interactions of toxic agents, and potential treatment targets. While these models have limitations in terms of extrapolation to their human counterparts, they nevertheless provide a unique opportunity to translate experimental findings into novel strategies that permit early detection of lung disease and timely therapeutic intervention.

2. LPS Model of Acute Lung Injury

2.1. Biochemical and Morphological Features

Acute lung injury (ALI) is an important feature of various pulmonary diseases, including pneumonia and respiratory distress syndrome [

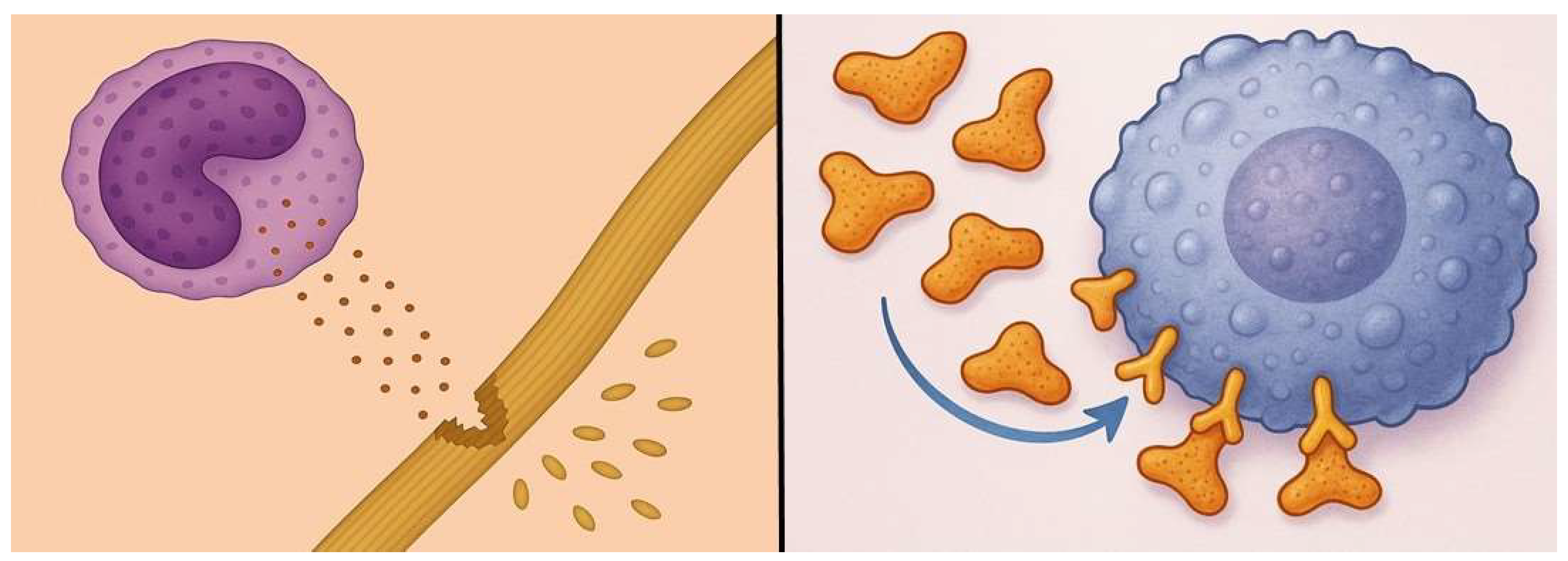

10]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of Gram-negative bacteria’s outer membrane, potentiates the acute inflammatory response in both humans and animal models by inducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines that activate an inflammatory cascade that recruits additional immune cells to the lung (

Figure 1) [

11,

12]. A critical component of this reaction is the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to endothelial cell injury, an influx of protein-rich edema fluid into the alveolar space, and impaired gas exchange [

13].

While a single intratracheal or intraperitoneal treatment with LPS consistently induces an acute inflammatory response, the influx of neutrophils and macrophages is transitory and may not fully encompass chronic lung injury or repair processes relevant to the human condition [

14,

15]. Furthermore, not all ALI is induced by infections involving LPS, which may limit the model’s extrapolation to other forms of the disease [

16].

Nevertheless, the LPS model provides a simple, reproducible means of determining the effects of anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic agents by allowing precise monitoring of drug effects on lung function parameters, histopathological changes, cytokine profiles, and immune cell dynamics [

17]. This information is critical to developing dosing regimens and appropriate endpoints in clinical trials.

2.2. Synergistic Effect Between LPS and Cigarette Smoke

While prolonged inhalation of cigarette smoke is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the more immediate effects are unclear [

18]. Brief exposure to smoke does not cause significant pulmonary injury and may have adverse consequences only if underlying disease is present [

19,

20]. This concept is particularly relevant to second-hand smoke, whose effects are more subtle and require concomitant lung injury to induce an inflammatory response.

Interactions between cigarette smoke and concurrent pulmonary disease may involve the activation of shared proinflammatory pathways [

21,

22]. For example, oxidants in smoke could amplify the effects of reactive oxygen species induced by secondary lung injury [

23]. Likewise, smoke-related increases in various cytokines could increase a pre-existing population of inflammatory cells [

24]. Consequently, even short-term exposure to second-hand smoke might enhance an otherwise indolent disease process. Such exposure to second-hand smoke could also predispose the normal lung to injury by other agents.

To test these hypotheses, hamsters were exposed to second-hand cigarette smoke for 2 hours per day over 3 days before or after intratracheal instillation of LPS [

25]. In both cases, short-term inhalation of cigarette smoke enhanced a number of inflammatory parameters. However, pretreatment with smoke had a greater proinflammatory effect than post-treatment, resulting in a 17% higher inflammatory index, a 25% increase in tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1)-labeled macrophages, a 27% increase in apoptotic cells, and a 284% increase in BAL neutrophils.

The reasons for this disparity are unclear, but it may involve differences in how the lung responds to the temporal relationship between cigarette smoke and LPS. Because cigarettes contain numerous toxins, pre-exposure to cigarette smoke may activate a large number of inflammatory mechanisms that are synergistically enhanced by endotoxin [

26]. Conversely, pretreatment with a single toxin such as LPS may activate fewer inflammatory processes, thereby limiting the degree of synergy with cigarette smoke.

Although these studies focused on the role of cigarette smoke, other inhaled toxins may have similar effects. Both outdoor and indoor air pollutants may potentiate the activity of underlying pulmonary disease. Synergistic interactions involving even very low levels of environmental toxins may perpetuate subacute inflammatory reactions that cause significant lung injury over time (

Figure 2).

2.3. Role of Endothelin in LPS-Induced Lung Injury

We have previously used the LPS model to determine whether the effects of LPS could be mitigated by decreasing the level of endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent vasoconstrictor [

27,

28]. This mediator was chosen as a target molecule because it also activates neutrophils and induces the release of a variety of proinflammatory cytokines by monocytes (

Figure 3) [

29,

30]. Our studies showed that pretreatment with a novel endothelin receptor antagonist (HJP272), one hour prior to intratracheal instillation of LPS, significantly reduced a number of inflammatory parameters, including lung histopathological changes, TNFR1 expression by BALF macrophages, and alveolar septal cell apoptosis. Conversely, exogenous administration of ET-1 increased LPS-induced lung injury, as measured by BALF neutrophils and TNFR1-positive macrophages [

31].

The anti-inflammatory effects of an endothelin-converting enzyme inhibitor, phosphoramidon, were also studied in the LPS lung model using a similar group of inflammatory endpoints [

32]. Pretreatment with this agent similarly attenuated the effects of LPS but to a greater extent than HJP272, which may be due to the fact that phosphoramidon completely blocks ET-1 activity, whereas HJP272 only binds to one of the two main endothelin receptors that regulate inflammatory cell influx into the lung.

In the case of both HJP272 and phosphoramidon, modifying the initial stages of the inflammatory process may be necessary to reduce the effects of LPS. Pretreatment with a single dose of HJP272 decreased a number of inflammatory processes, while administration of phosphoramidon at one hour following initiation of lung injury abrogated its inhibitory effect on the influx of neutrophils into the lung.

3. Elastase-Induced Pulmonary Emphysema

3.1. Biochemical and Morphological Features

In pulmonary emphysema, a subacute inflammatory process releases enzymes that slowly degrade alveolar wall elastic fibers, reducing their ability to store the energy needed to expel air from the lungs (

Figure 4) [

33,

34,

35,

36]. These fibers have a specialized structure consisting of a central elastin protein surrounded by layers of microfibrils [

37]. The elastin component consists of crosslinked peptide chains containing hydrophobic regions that absorb energy and are responsible for the elastic properties of the fibers [

38]. Loss of these fibers due to enzymatic or oxidative breakdown causes uneven transmission of mechanical forces in the lung, leading to alveolar wall distension and rupture [

39,

40].

Two of the elastin crosslinks, desmosine and isodesmosine (DID), are unique to this protein and may, therefore, serve as a biomarker for the breakdown of elastic fibers [

41,

42]. Increased levels of these crosslinks in sputum, blood, or urine may indicate the presence of COPD and emphysema in particular [

43,

44]. Measurements of BALF DID at 1 week following intratracheal instillation of elastase into hamster lungs showed a significant increase in these crosslinks compared to controls, consistent with elastic fiber injury [

45].

Microscopic examination of the elastase-treated lungs revealed a variable degree of alveolar wall distention and rupture due to the uneven distribution of the instilled elastase (

Figure 5). These changes were accompanied by interstitial and airway inflammation, which was reflected by a significant increase in the percentage of BALF neutrophils.

3.2. The Ratio of Free to Total Desmosine as a Biomarker for Pulmonary Emphysema

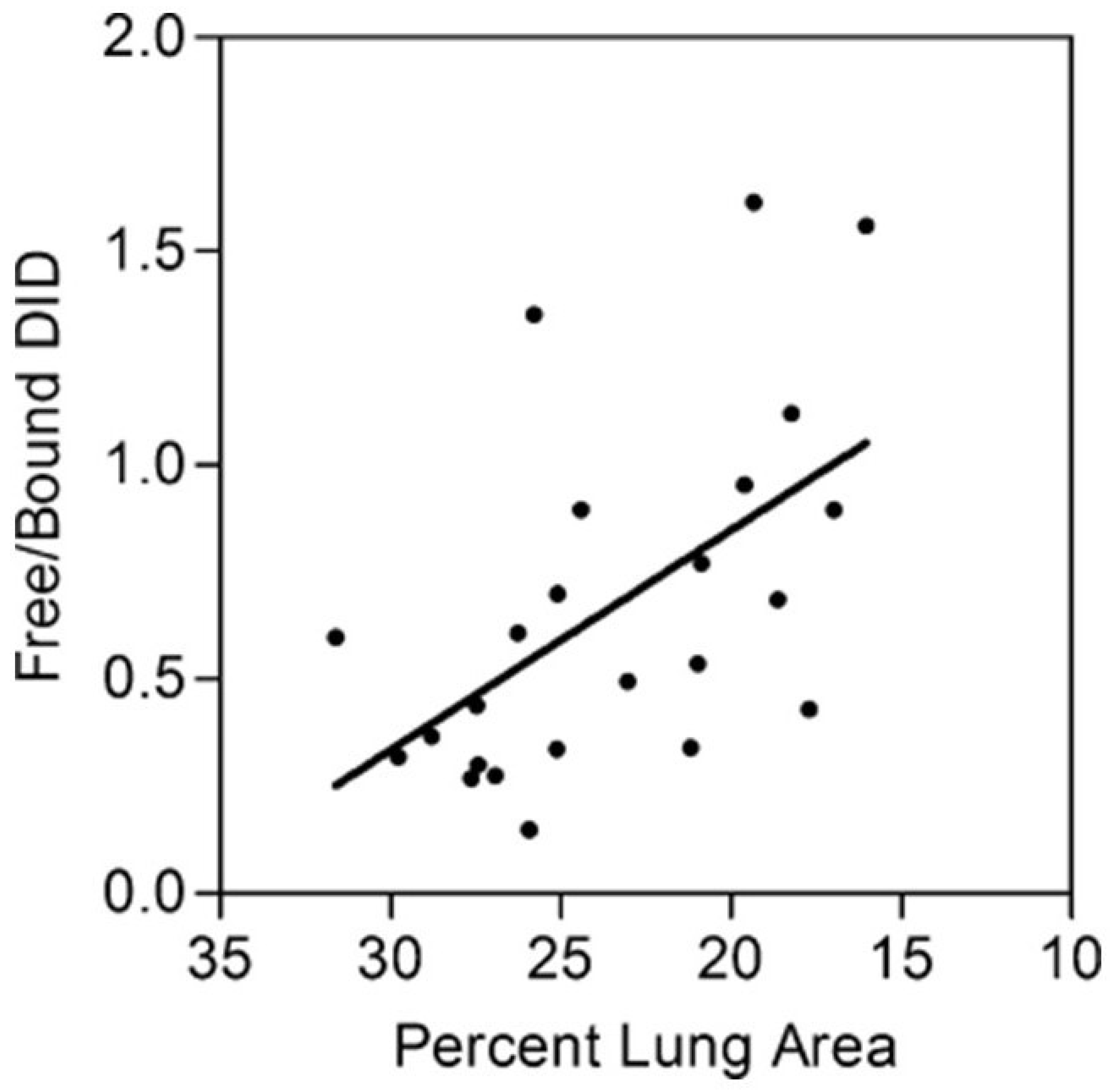

Since various studies have shown that total DID levels may not be a sensitive biomarker for airspace enlargement, we used the ratio of peptide-free to peptide-bound DID, rather than the absolute quantity of these crosslinks, as an indicator of airspace enlargement in a hamster model of elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema [

45]. Peptide-bound DID refers to crosslinks attached to the elastin protein, whereas free DID is not linked to other amino acids.

The free to bound DID ratio was measured in BALF recovered from hamsters instilled intratracheally with either 5 or 10 U of elastase and controls given the saline vehicle alone [

45]. Treating the lungs with different doses of elastase produced a range of emphysematous changes and facilitated the comparison of the free to bound DID ratio with emphysematous changes, as measured by relative lung surface area. The results showed a statistically significant negative correlation between this ratio and lung surface area, which is inversely proportional to alveolar diameter (

Figure 6). The relative increase in free DID may reflect the effects of both elastase activity and mechanical forces that facilitate the separation of intact crosslinks from their surrounding peptides.

3.3. Combining Elastase-Induced Emphysema with LPS

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) may result in accelerated loss of pulmonary function [

46]. To better understand the effects of acute inflammation on pre-existing elastic fiber injury, our laboratory developed a hamster model that uses intratracheal instillation of LPS to augment pulmonary emphysema previously induced by the administration of elastase [

47]. In contrast to previous models involving either multiple instillations of elastase before treatment with LPS or a single administration of LPS several weeks after elastase, this model uses a single low dose of the enzyme and decreases the interval between instillation of the two agents to a single week [

48,

49]. The design enhances the effect of LPS compared to elastase and facilitates the identification of potential synergistic interactions.

Using this model, we determined whether mild alterations in the structure of elastic fibers increased their susceptibility to LPS-induced injury, as measured by BALF levels of desmosine and isodesmosine (DID). The effect of combining elastin peptides with LPS was also examined to assess the proinflammatory role of fragmented elastic fibers (

Figure 7).

Animals treated with elastase and LPS displayed prominent fragmentation and splaying of lung elastic fibers. Less pronounced changes were seen following treatment with either elastase or LPS alone. These findings were reflected by significantly higher levels of free BALF DID following treatment with both agents compared to the elastase-only group or untreated controls. Consistent with this process, a marked increase in airspace enlargement was seen in animals given both elastase and LPS compared to all other groups.

4. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Pulmonary Emphysema

4.1. Biochemical and Morphological Features

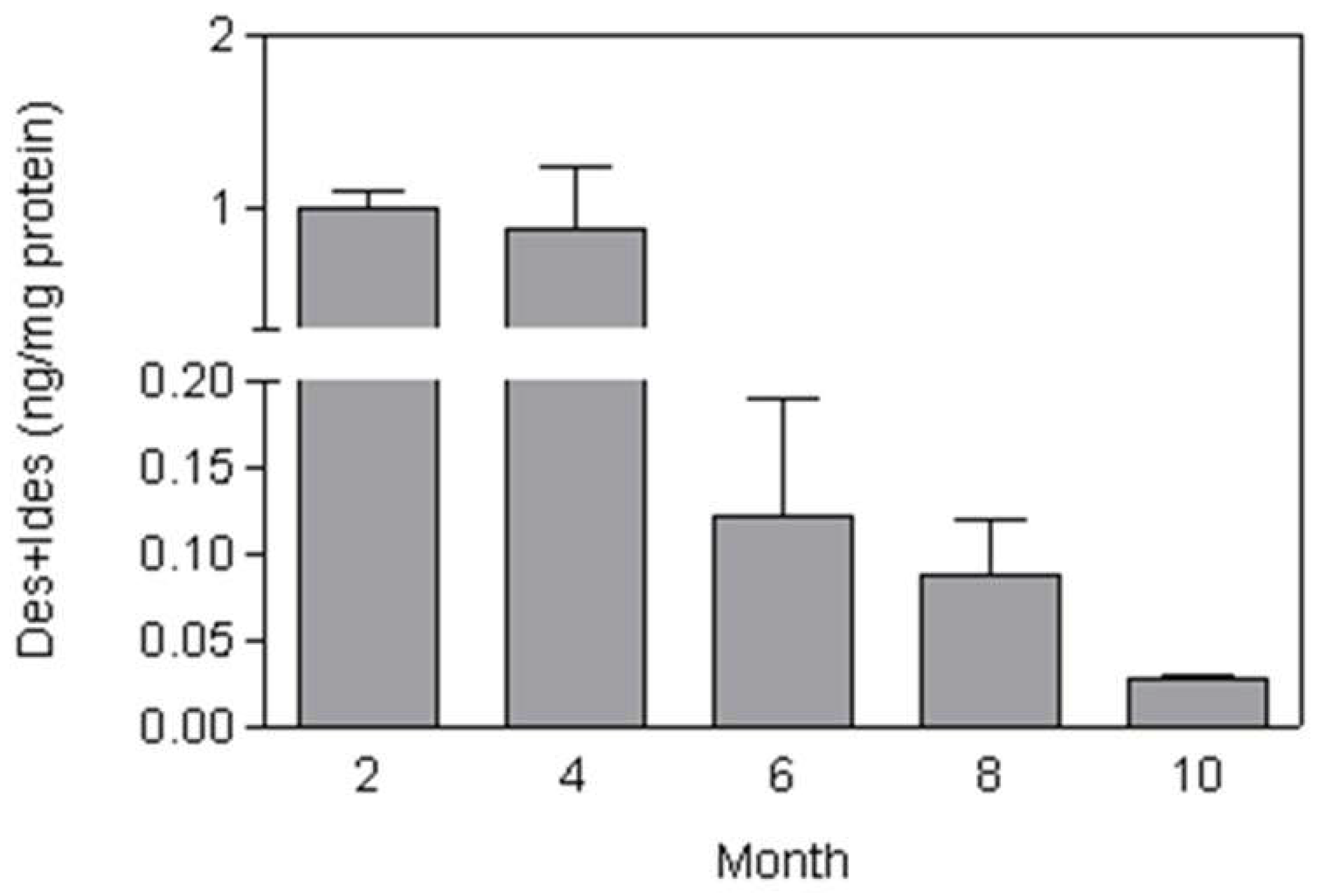

Mice treated with whole-body exposure to cigarette smoke for 2 hours each day, 5 days per week, over 10 months showed a gradual increase in airspace enlargement that became microscopically evident at 2 months [

50]. Total lung DID was increased at two months, then markedly decreased over the next four months before undergoing a secondary increase over the remaining course of the study. These findings reflect a dynamic balance between elastic fiber injury and repair over time and are consistent with the progressive decline in BALF DID levels between 4 and 10 months (

Figure 8).

Airspace enlargement leveled off in the smoke-exposed mice after 4 months, possibly related to increased lung DID content. Enhanced deposition of elastin and other extracellular matrix components could decrease alveolar wall rupture due to mechanical stress. This hypothesis is supported by clinical studies showing an association between interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and cigarette smoking [

51,

52].

4.2. The Effect of Aerosolized Hyaluronan on Airspace Enlargement

Although the investigation of potential agents for treating pulmonary emphysema has focused on elastase inhibitors, this laboratory has developed a novel method of preventing elastic fiber injury by administering aerosolized hyaluronan (HA). Animals exposed to HA before intratracheal instillation or elastase had significantly less airspace enlargement than untreated controls [

53]. This effect may be due to the attachment of HA to lung elastic fibers, which provides a protective coating against elastases and other injurious agents [

54].

To further test this concept, the effect of aerosolized HA was studied in a mouse model of cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema. The smoking model provides a more stringent test of the therapeutic effects of HA because airspace enlargement develops over a period of months and more closely resembles the development of the human disease [

55]. Mice were treated with an aerosolized solution of 0.1 percent HA (average molecular weight of 150 kDa) before a 2-hour exposure to cigarette smoke. The procedure was repeated 5 days per week over 6 months. While smoke-induced airspace enlargement leveled off over time, animals treated with HA nevertheless showed a significant reduction in airspace enlargement during the study (

Figure 9).

To determine the location of the HA within the lung, animals were treated with a single 1-hour exposure to fluorescein-labeled HA. Following treatment, a linear fluorescence pattern was associated with interstitial, pleural, and vascular elastic fibers (

Figure 10). At 24 hours, the fluorescence was diminished in intensity, consistent with the clearance of the exogenous HA from the lung.

These findings provided the rationale for translational studies involving a clinical trial to determine the efficacy of HA in COPD patients with alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency [

56]. Levels of DID in plasma, urine, and sputum were measured at weekly intervals to assess the effect of treatment on lung elastic fiber degradation. Inhalation of a 0.01 percent solution of aerosolized HA twice daily for 28 days significantly decreased the amount of free DID in urine. This finding was consistent with earlier measurements of free BALF DID in elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema, supporting its use as a biomarker for therapeutic efficacy.

5. Bleomycin Model of Pulmonary Fibrosis

5.1. Biochemical and Morphological Features

The bleomycin (BLM) model is commonly used to study pulmonary fibrosis because it has morphological features that resemble the human disease, including an influx of inflammatory cells, alveolar epithelial cell hyperplasia, airspace distention, and interstitial fibrosis [

57,

58]. Intratracheal instillation of BLM induces the formation of complexes between this agent and Fe

2+, which generate free radicals that damage DNA, leading to necrosis of type 1 alveolar epithelium and exposure to underlying basement membranes (

Figure 11) [

59]. This process is accompanied by a marked influx of neutrophils, proliferation of type 2 alveolar cells, and the deposition of collagen and other extracellular components in the lung interstitium [

60].

The rapid development of inflammation and fibrosis following the instillation of BLM suggests that this form of lung injury may be better characterized as a wound-healing phenomenon rather than irreversible lung remodeling. The changes induced by BLM do not replicate the gradual development of the human disease and can regress over time [

61]. Nevertheless, this model has provided insight into the mechanisms that may be responsible for the development of its human counterpart. The rapid development of fibrosis facilitates the evaluation of drug candidates over the entire course of the disease. By varying the temporal relationship between these agents and BLM instillation, it may be possible to determine where they exert their most significant effect on the disease process.

5.2. The Effect of Endothelin Inhibition

To evaluate the temporal relationship between BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis and treatment with the HJP272 endothelin antagonist, hamsters were given an intraperitoneal injection of this agent one hour before intratracheal instillation of BLM or 24 h afterward [

62]. During the following month, the pulmonary inflammatory response was assessed by measuring various parameters, including lung histopathological changes, neutrophil content in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), lung collagen content, BALF macrophage TNFR1, and alveolar septal cell apoptosis.

Pretreatment with HJP272 resulted in a significant decrease in all these parameters compared to animals receiving BLM alone, whereas post-treatment was ineffective in reducing their levels. This discrepancy was most evident morphologically, where the lungs of animals pretreated with HJP272 showed much less fibrosis, suggesting that the early inflammatory events may be primarily responsible for the extent of lung injury (

Figure 12). These findings are consistent with clinical trials showing that commercially available ERAs, such as ambrisentan and bosentan, are ineffective in treating pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis [

63,

64,

65]. However, this finding does not preclude the use of ERAs as prophylactic agents, which may be given in combination with drugs whose side effects include pulmonary fibrosis.

The limited efficacy of ERAs may be related to the emergent properties of pulmonary fibrosis, in which interactions at multiple levels of scale result in spontaneous reorganization of lung structure [

66,

67]. The process of emergence is a common feature of complex systems that include chemical reactions, epidemics, and disease pathogenesis [

68]. It may be represented by percolation models based on the random movement of fluids through interconnecting channels [

69]. The convergence of isolated currents in the network reaches a critical threshold involving a phase transition that changes the structure and behavior of the system. In the case of pulmonary fibrosis, the spread of the extracellular matrix through the lung interstitium is similar to the diffusion of fluid through a percolation network, producing analogous changes in the chemical and physical properties of the lung.

The deposition of matrix components alters the elastic modulus of the alveolar walls and modifies the transmission of mechanical forces related to breathing. This process induces further interstitial injury and repair, resulting in the self-propagation of the disease on a much larger scale [

70]. Computer-generated models of pulmonary fibrosis support the validity of this mechanism by showing that local changes in alveolar wall structure evolve into global morphological alterations that resemble those seen in the human disease [

71,

72].

The concept of emergence emphasizes the need for developing biomarkers with the sensitivity and specificity to detect and treat the disease before it evolves into more widespread lung injury that is amenable to therapeutic intervention [

73]. Identifying a biomarker with these properties might have the additional effect of permitting more timely administration of ERAs, thereby enhancing their therapeutic efficacy.

6. Chemical Versus Genetic Models

In contrast to chemical models that involve the administration of toxic substances such as LPS, elastase, and cigarette smoke, genetic models are designed to study the role of specific proteins in the pathogenesis of lung disease. Knockout models involve deleting or inactivating specific genes to study the resulting phenotypic changes. For instance, the genetic deletion of cytokines provides important information about various pulmonary inflammatory mechanisms [

74,

75].

Conversely, knock-in models are designed to insert a specific mutation into a gene, allowing investigators to study diseases that arise from particular genetic variants [

76]. Mice with a specific mutation in the CFTR gene, which causes cystic fibrosis, can simulate the human condition, enabling studies on the impacts of gene insertion on ion transport, mucus viscosity, and susceptibility to infections [

77]. These types of studies may be used to design clinical trials of therapies aimed at correcting the dysfunctional transport mechanism in cystic fibrosis.

While genetic models have become important tools in studying these diseases, they also have limitations. Many lung diseases arise from the interaction of multiple genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that these models cannot represent. Furthermore, lung diseases can manifest differently among individuals due to variations in genetics, immune responses, and environmental factors, limiting the predictive power of genetic models.

In contrast, chemical models can replicate the effects of pollutants or irritants, which are critical to the development of various lung diseases. Chemical models allow investigation of the immediate physiological effects of exposure to toxic substances, which is particularly useful in understanding the pathogenesis of diseases like ALI and COPD. These models can be precisely controlled with regard to the concentration, duration, and timing of exposures to single or multiple toxins, providing consistent conditions to study disease mechanisms. This approach also eliminates the potential confounding influence of genetic manipulation, making it easier to establish causal relationships.

7. Strategies for Addressing the Limitations of Animal Models

Based on the examples presented in the current paper, animal models play a critical role in investigating lung disease. Nevertheless, models involving a single dose of a toxic agent may not accurately represent the corresponding human disease [

78]. The compression of the timeline of the morphological changes in these models cannot reproduce the long-term evolution of changes at multiple levels of scale that are an essential characteristic of pulmonary emphysema, interstitial fibrosis, and other lung disorders [

79,

80].

Despite these limitations, the strength of animal models may involve the ability to study mechanisms of injury from different standpoints. The use of multiple models to determine the consistency of responses to therapeutic agents is an example of this process. The findings associated with the use of HJP272 in the BLM model were replicated in another model of pulmonary fibrosis induced by the cardiac antiarrhythmic agent, amiodarone. Since this model involves different mechanisms of injury than the BLM model, the similarity in results is more meaningful regarding the therapeutic potential of ERAs to mitigate human pulmonary fibrosis.

Furthermore, varying the routes of administration of the disease-inducing agent can yield important insights into the systemic factors involved in the development of human lung disease. Intratracheal versus intravenous instillation can lead to disparate responses in terms of the lung cells affected and the timeline of injury and repair. While intratracheal instillation may be more effective in producing lung changes, other toxin or drug delivery routes may better reflect the clinical circumstances surrounding the development and potential treatment of the human disease. In particular, the effect of endothelial cell injury on the influx of inflammatory cells and protein-rich fluid into the lung may be better studied using a model of lung injury induced by intravenous or intraperitoneal administration of toxic agents.

The current paper shows that animal models are especially suited to investigating the potential synergistic interactions between pulmonary toxins. For example, pretreatment with brief exposure to cigarette smoke significantly enhanced LPS-induced lung inflammation. Further investigation of this phenomenon revealed that exogenously administered endothelin facilitated the influx of neutrophils that may be sequestered in pulmonary capillaries following smoke exposure. This finding suggests that LPS-induced activation of endothelin may be responsible for the synergistic interaction of this agent with cigarette smoke.

Pretreatment with a low dose of elastase also had a synergistic effect on LPS-induced lung inflammation [

47]. This finding prompted the use of elastin peptides to determine their proinflammatory activity in the LPS model. Combining the two agents significantly increased BALF levels of neutrophils and free DID compared to either agent alone. These results emphasize the proinflammatory role of elastin peptides released from degraded elastic fibers and their ability to potentiate the effects of other injurious agents, such as pathogenic organisms and environmental pollutants. The synergistic interactions revealed by the combined use of elastin peptides and LPS may provide a better understanding of how acute exacerbations in patients with COPD may lead to the permanent loss of lung function.

8. Conclusions

Animal models have emerged as an invaluable tool in understanding the complex pathogenesis of various human lung diseases. These models serve as critical platforms for exploring the multifactorial mechanisms underlying these disorders. By illustrating various experimental approaches in multiple models of pulmonary disease, the current paper emphasizes the role of animal models in identifying potential synergic interactions between toxic agents and how the temporal dynamics of exposure can critically influence the severity of lung injury. The continued refinement of these models will improve their relationship to human pulmonary diseases and facilitate the translation of experimental findings to therapeutic interventions that can slow the progression of lung injury and reduce the risk of respiratory failure.

References

- Churg, A.; Cosio, M.; Wright, J.L. Mechanisms of cigarette smoke-induced COPD: insights from animal models. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2008, 294(4), L612–L631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, P.; Wu, C.W.; Pham, A.; Zeki, A.A.; Royer, C.M.; Kodavanti, U.P.; Takeuchi, M.; Bayram, H.; Pinkerton, K.E. Animal models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2023, 26(5), 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.L.; Churg, A. Animal models of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2010, 4(6), 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, F.; Lin, Y. Cigarette smoke synergizes lipopolysaccharide-induced interieukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor–α secretion from macrophages via substance P–mediated nuclear factor–κB activation. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 2011, 44(3), 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J. The Potential Role of Cigarette Smoke, Elastic Fibers, and Secondary Lung Injury in the Transition of Pulmonary Emphysema to Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(21), 11793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.; Morsy, M.A.; Jacob, S. Dose translation between laboratory animals and human in preclinical and clinical phases of drug development. Drug development research 2018, 79(8), 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G. Preclinical Drug Development. In Pharmaceutical Medicine and Translational Clinical Research; Academic Press, 2018; pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Iadarola, P.; Luisetti, M. The role of desmosines as biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2013, 7(2), 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J. Desmosine: The Rationale for Its Use as a Biomarker of Therapeutic Efficacy in the Treatment of Pulmonary Emphysema. Diagnostics 2025, 15(5), 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushianthan, A.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Postle, A.D.; Cusack, R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Postgraduate medical journal 2011, 87(1031), 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bai, C.; Wang, X. The value of the lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury model in respiratory medicine. Expert review of respiratory medicine 2010, 4(6), 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocco, A.; Ortiz, L.A. Role of metabolic reprogramming in proinflammatory cytokine secretion from LPS or silica-activated macrophages. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 936167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhayaza, R.; Haque, E.; Karbasiafshar, C.; Sellke, F.W.; Abid, M.R. The relationship between reactive oxygen species and endothelial cell metabolism. Frontiers in chemistry 2020, 8, 592688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domscheit, H.; Hegeman, M.A.; Carvalho, N.; Spieth, P.M. Molecular dynamics of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in rodents. Frontiers in physiology 2020, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, L.; Morales-Quinteros, L.; Puig, F.; Camprubi-Rimblas, M.; Guillamat-Prats, R.; Gómez, M.N.; Tijero, J.; Blanch, L.; Matute-Bello, G.; Artigas, A. Comparison of direct and indirect models of early induced acute lung injury. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute-Bello, G.; Frevert, C.W.; Martin, T.R. Animal models of acute lung injury. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2008, 295(3), L379–L399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Xu, S.; Lam, T.Y.W.; Liao, W.; Wong, W.F.; Ge, R. ISM1 suppresses LPS-induced acute lung injury and post-injury lung fibrosis in mice. Molecular Medicine 2022, 28(1), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vaart, H.; Postma, D.S.; Timens, W.; Ten Hacken, N.H. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: a review. Thorax 2004, 59(8), 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauchet, L.; Hulo, S.; Cherot-Kornobis, N.; Matran, R.; Amouyel, P.; Edmé, J.L.; Giovannelli, J. Short-term exposure to air pollution: associations with lung function and inflammatory markers in non-smoking, healthy adults. Environment international 2018, 121, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.E.C.; Shin, S.; Hwang, J.H. Inflammatory diseases of the lung induced by conventional cigarette smoke: a review. Chest 2015, 148(5), 1307–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, J.; Song, Q.; Cheng, W.; Chen, P. The role of HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 signaling pathways in cigarette smoke-induced inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immunity, inflammation and disease 2022, 10(11), e711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugg, S.T.; Scott, A.; Parekh, D.; Naidu, B.; Thickett, D.R. Cigarette smoke exposure and alveolar macrophages: mechanisms for lung disease. Thorax 2022, 77(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.S.; Park, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.Y. Cigarette smoke-induced reactive oxygen species formation: a concise review. Antioxidants 2023, 12(9), 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzelak, A.; Ratajczak, A.; Adamiec, A.; Feleszko, W. Tobacco smoke induces and alters immune responses in the lung triggering inflammation, allergy, asthma and other lung diseases: a mechanistic review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2018, 15(5), 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.S.; Nadkarni, P.P.; Cerreta, J.M.; Ma, S.; Cantor, J.O. Short-term cigarette smoke exposure potentiates endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation. Exp Lung Res. 2007, 33(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, D.K.; Hirata, F.; Rishi, A.K.; Gairola, C.G. Cigarette smoke, inflammation, and lung injury: a mechanistic perspective. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B 2009, 12(1), 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricio, A.S.; Rae, G.A.; D’Orléans-Juste, P.; Souza, G.E. Endothelin-1 as a central mediator of LPS-induced fever in rats. Brain research 2005, 1066(1–2), 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Kleniewska, P.; Kolodziejczyk, M.; Skibska, B.; Goraca, A. The role of endothelin-1 and endothelin receptor antagonists in inflammatory response and sepsis. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis 2015, 63, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.D.; Machado, F.S.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Desruisseaux, M.S. Endothelin-1 and its role in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Life sciences 2014, 118(2), 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarpelon, A.C.; Pinto, L.G.; Cunha, T.M. Endothelin-1 induces neutrophil recruitment in adaptive inflammation via TNFα and CXCL1/CXCR2 in mice. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012. Retrieved from https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/y11-116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, T.; Liu, X.J.; Patel, H.; Stephani, R.; Cantor, J.O. Preferential recruitment of neutrophils by endothelin-1 in acute lung inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide or cigarette smoke. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008, 3(3), 477–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhavsar, T.M.; Cerreta, J.M.; Liu, M.; Reznik, S.E.; Cantor, J.O. Phosphoramidon, an endothelin-converting enzyme inhibitor, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Experimental Lung Research 2008, 34(3), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J. The role of the extracellular matrix in the pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary emphysema. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(19), 10613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voynow, J.A.; Shinbashi, M. Neutrophil elastase and chronic lung disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11(8), 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.C.; De, S.; Mishra, P.K. Role of proteases in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Frontiers in pharmacology 2017, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagiola, M.; Reznik, S.; Riaz, M.; Qyang, Y.; Lee, S.; Avella, J.; Turino, G.; Cantor, J. The relationship between elastin cross linking and alveolar wall rupture in human pulmonary emphysema. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2023, 324(6), L747–L755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozel, B.A.; Mecham, R.P. Elastic fiber ultrastructure and assembly. Matrix Biology 2019, 84, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trębacz, H.; Barzycka, A. Mechanical properties and functions of elastin: an overview. Biomolecules 2023, 13(3), 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roan, E.; Waters, C.M. What do we know about mechanical strain in lung alveoli? American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2011, 301(5), L625–L635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.; Ochs, M. The micromechanics of lung alveoli: structure and function of surfactant and tissue components. Histochemistry and cell biology 2018, 150, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisetti, M.; Ma, S.; Iadarola, P.; Stone, P.J.; Viglio, S.; Casado, B.; Lin, Y.Y.; Snider, G.L.; Turino, G.M. Desmosine as a biomarker of elastin degradation in COPD: current status and future directions. European Respiratory Journal 2008, 32(5), 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.T.J.; Chaudhuri, R.; Albarbarawi, O.; Barton, A. Clinical validity of plasma and urinary desmosine as biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2012, 67(6), 502, https://thorax.bmj.com/content/67/6/502.short. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Leitao Filho, F.S.; Shahangian, K.; Takiguchi, H.; Sin, D.D. Blood and sputum protein biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Expert review of proteomics 2018, 15(11), 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrarotti, I.; Corsico, A.G.; Stolk, J.; Ottaviani, S.; Fumagalli, M.; Janciauskiene, S.; Iadarola, P. Advances in identifying urine/serum biomarkers in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency for more personalized future treatment strategies. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2017, 14(1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, S.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Turino, G.; Cantor, J. The ratio of free to bound desmosine and isodesmosine may reflect emphysematous changes in COPD. Lung 2015, 193, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogea, S.P.; Tudorache, E.; Fildan, A.P.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Marc, M.; Oancea, C. Risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. The clinical respiratory journal 2020, 14(3), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraban, S.; Gu, G.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Turino, G.; Cantor, J. The proinflammatory activity of structurally altered elastic fibers. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2020, 63(5), 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.V.; Rocha, N.N.; Santos, R.S.; Rocco, M.R.M.; de Magalhães, R.F.; Silva, J.D.; et al. Endotoxin-Induced emphysema exacerbation: a novel model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations causing cardiopulmonary impairment and diaphragm dysfunction. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Fujinawa, R.; Ota, F.; Kobayashi, S.; Angata, T.; Ueno, M.; et al. A single dose of lipopolysaccharide into mice with emphysema mimics human chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation as assessed by micro-computed tomography. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013, 49, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J.O.; Cerreta, J.M.; Ochoa, M.; Ma, S.; Liu, M.; Turino, G.M. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronan on smoke-induced elastic fiber injury: does delayed treatment affect efficacy? Lung 2011, 189, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, M.R. Pathologic features of smoking-related lung diseases, with emphasis on smoking-related interstitial fibrosis and a consideration of differential diagnoses. In Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology; WB Saunders, 2018; Volume 35, pp. 315–315. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, D.; Rosas, I.O. Tobacco smoke–induced lung fibrosis and emphysema. Annual review of physiology 2014, 76(1), 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J.O.; Cerreta, J.M.; Keller, S.; Turino, G.M. Modulation of Airspace Enlargement in Elastase-Induced Emphysema by Intratracheal Instalment of Hyaluronidase and Hyaluronic Acid. Experimental lung research 1995, 21(3), 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J.O.; Cerreta, J.M.; Armand, G.; Turino, G.M. Further investigation of the use of intratracheally administered hyaluronic acid to ameliorate elastase-induced emphysema. Experimental lung research 1997, 23(3), 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J.O.; Cerreta, J.M.; Ochoa, M.; Ma, S.; Chow, T.; Grunig, G.; Turino, G.M. Aerosolized hyaluronan limits airspace enlargement in a mouse model of cigarette smoke–induced pulmonary emphysema. Experimental lung research 2005, 31(4), 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J.O.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Campos, M.A.; Strange, C.; et al. A 28-day clinical trial of aerosolized hyaluronan in alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency COPD using desmosine as a surrogate marker for drug efficacy. Respiratory Medicine 2021, 182, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, A.; Yang, F.; Xie, C.; Du, W.; Mohammadtursun, N.; Wang, B.; Le, J.; Dong, J. Pulmonary fibrosis model of mice induced by different administration methods of bleomycin. BMC pulmonary medicine 2023, 23(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kuninaka, Y.; Mukaida, N.; Kondo, T. Immune mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24(4), 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Qin, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, F.; Huo, F.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; Lin, P.; Zhou, G.; Yan, J. Inhibition of ferroptosis and iron accumulation alleviates pulmonary fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Redox biology 2022, 57, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Latta, V.; Cecchettini, A.; Del Ry, S.; Morales, M.A. Bleomycin in the setting of lung fibrosis induction: from biological mechanisms to counteractions. Pharmacological research 2015, 97, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotton, C.J.; Chambers, R.C. Bleomycin revisited: towards a more representative model of IPF? American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2010, 299(4), L439–L441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Khadtare, N.; Patel, H.; Stephani, R.; Cantor, J. Time-dependent effects of HJP272, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics 2017, 45, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, G.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Egan, J.J.; Kawut, S.M.; Flaherty, K.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Nathan, S.D.; Wells, A.U.; Collard, H.R.; Costabel, U. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with ambrisentan: a parallel, randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 2013, 158(9), 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Wang, J.X.; Xie, Z.F.; Li, L.H.; Li, B.; Huang, F.F.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.L. Bosentan and ambrisentan in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a meta-analysis. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 28(3). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Y. A comprehensive comparison of the safety and efficacy of drugs in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a network meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2024, 24(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suki, B.; Bates, J.H. Lung tissue mechanics as an emergent phenomenon. Journal of applied physiology 2011, 110(4), 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard-Duke, J.; Agro, S.M.; Csordas, D.J.; Bruce, A.C.; Eggertsen, T.G.; Tavakol, T.N.; Comlekoglu, T.; Barker, T.H.; Bonham, C.A.; Saucerman, J.J.; Taite, L.J. Multiscale computational model predicts how environmental changes and treatments affect microvascular remodeling in fibrotic disease. PNAS nexus 2025, 4(1), pgae551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, P.; Mansi, O. Nonlinearity in the epidemiology of complex health and disease processes. Theoretical medicine and bioethics 1998, 19, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, A.G.; Sahimi, M. Flow, transport, and reaction in porous media: Percolation scaling, critical-path analysis, and effective medium approximation. Reviews of Geophysics 2017, 55(4), 993–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, C.; Ulldemolins, A.; Narciso, M.; Almendros, I.; Farré, R.; Navajas, D.; López, J.; Eroles, M.; Rico, F.; Gavara, N. Multi-step extracellular matrix remodelling and stiffening in the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(2), 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Bates, J.H.; Casey, D.T.; Bartolák-Suki, E.; Lutchen, K.R.; Suki, B. Predicting alveolar ventilation heterogeneity in pulmonary fibrosis using a non-uniform polyhedral spring network model. Frontiers in Network Physiology 2023, 3, 1124223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, D.T.; Bou Jawde, S.; Herrmann, J.; Mori, V.; Mahoney, J.M.; Suki, B.; Bates, J.H. Percolation of collagen stress in a random network model of the alveolar wall. Scientific reports 2021, 11(1), 16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, H.H.; Darrow, J.J.; Caicedo, J.C.; Pentland, A. Prioritizing Early Disease Intervention. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 2023, 57(6), 1148–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Su, L.; Deng, C.; Huang, J.; Chen, G. Incomplete knockdown of MyD88 inhibits LPS-induced lung injury and lung fibrosis in a mouse model. Inflammation 2023, 46(6), 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.H.; Hsieh, W.Y.; Hsieh, J.S.; Liu, F.C.; Tsai, C.H.; Lu, L.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Wu, C.L.; Lin, C.S. Alternative roles of STAT3 and MAPK signaling pathways in the MMPs activation and progression of lung injury induced by cigarette smoke exposure in ACE2 knockout mice. International journal of biological sciences 2016, 12(4), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, A.; McGarry, M.P.; Lee, N.A.; Lee, J.J. The construction of transgenic and gene knockout/knockin mouse models of human disease. Transgenic research 2012, 21, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawenis, L.R.; Hodges, C.A.; McHugh, D.R.; Valerio, D.M.; Miron, A.; Cotton, C.U.; Liu, J.; Walker, N.M.; Strubberg, A.M.; Gillen, A.E.; Mutolo, M.J. A BAC transgene expressing human CFTR under control of its regulatory elements rescues Cftr knockout mice. Scientific Reports 2019, 9(1), 11828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E. Replacement strategies for animal studies in inhalation testing. Sci 2021, 3(4), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, L.; Single, A.B. Animal models reflecting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related respiratory disorders: translating preclinical data into clinical relevance. Journal of innate immunity 2020, 12(3), 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, P.; Ruggeri, B. Animal models of human disease: challenges in enabling translation. Biochemical pharmacology 2014, 87(1), 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).