Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

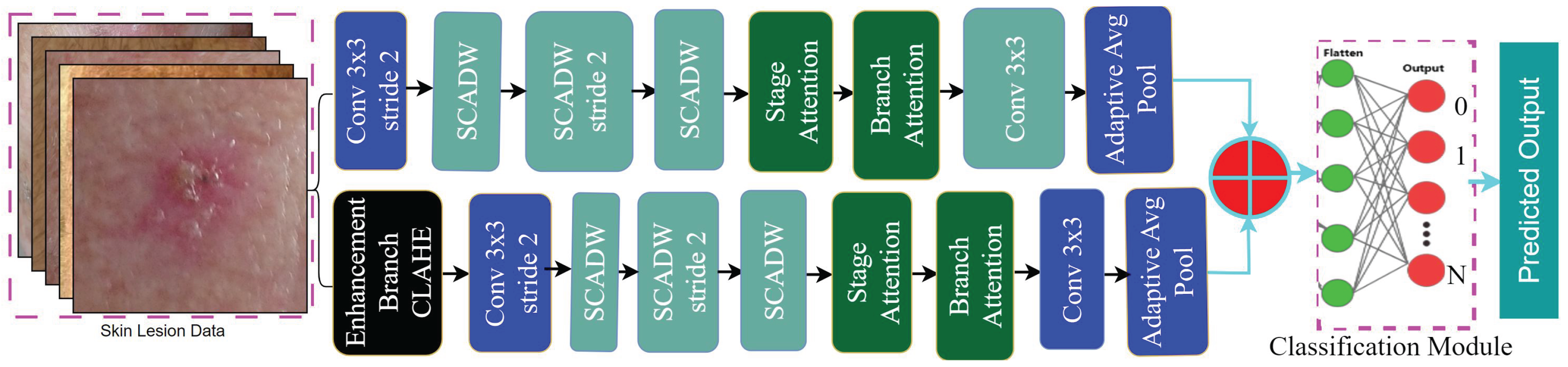

- We employed a novel hybrid attention dual-stream deep learning model specifically designed for skin lesion detection, which addresses the limitations of existing ensemble CNN models that are often too large and inefficient for contextual information processing.

- Our model effectively utilizes two distinct feature extraction branches: the first branch integrates a convolutional layer with three novel attention modules—Enhanced Separable Depthwise Convolution (SCAttn), branch attention, and stage attention—to capture both local and global hierarchical features from the original images.

- We enhance the input images in the second branch using Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to improve local contrast and reveal finer details. This enhancement allows for a more nuanced feature extraction through the same attention-based pipeline as the first branch, thereby achieving better feature representation while maintaining computational efficiency.

- The model combines features from both branches, leveraging the strengths of enhanced local contrast and advanced attention mechanisms to produce a comprehensive and robust feature set, which is subsequently fed into a classification module.

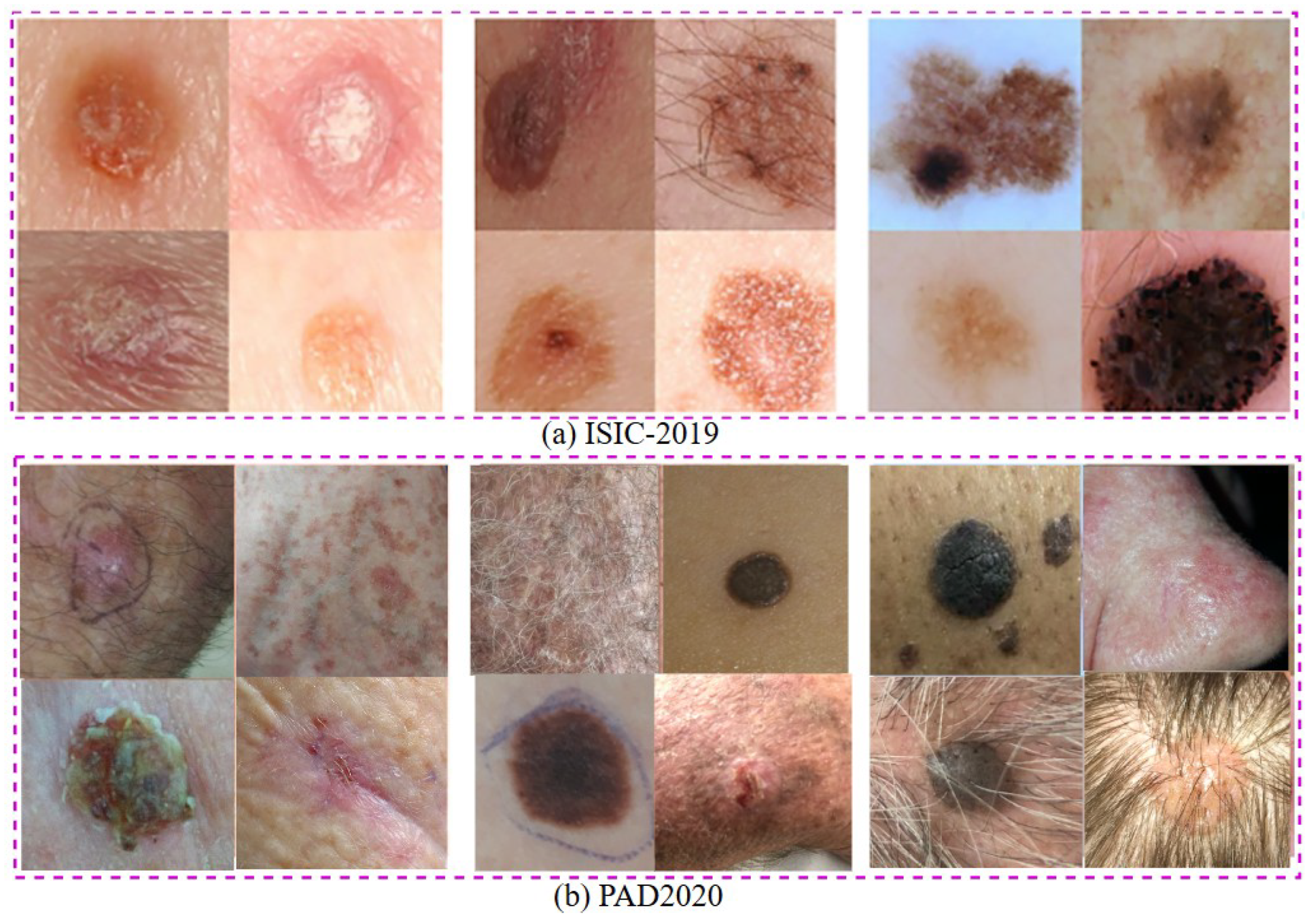

- In the extensive experiment with the PAD2020 and ISIC 2019 datasets, we assessed the proposed model and obtained an accuracy rate of 98.59%, of the PAD2020 surpassing the state-of-the-art performance by 2% and stable performance accuracy for the ISIC 2019 dataset. In addition, our model achieved stable performance accuracy for the ISIC-2019 dataset. This shows that the model is better at combining different attention mechanisms and feature improvement methods for accurate and useful skin cancer detection.

2. Literature Review

3. Dataset

4. Proposed Methodology

4.1. Image Pre-Processing

4.2. Data Balance

4.3. Image Enhancement CLAHE

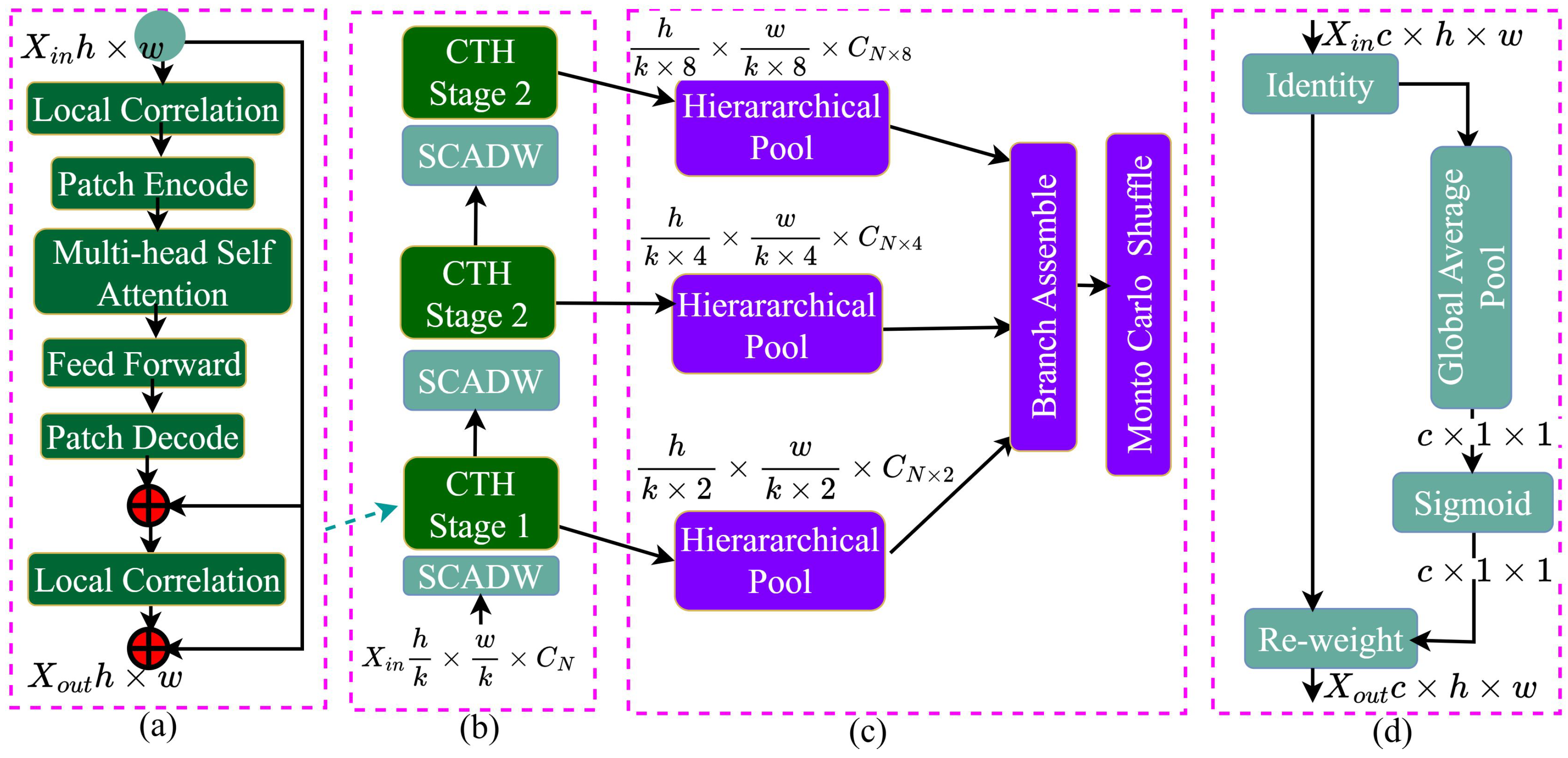

4.4. CTH Module

4.5. SCADW

- Depthwise Separable Convolution(DWSConv): The SCADW block begins with a depthwise separable convolution which consists of two main operations that are- 1) Depthwise Convolution operation that applies a single filter to each input channel separately, which helps in reducing the number of parameters and computational cost compared to standard convolution, 2) Pointwise Convolution that follows the depthwise convolution. Pointwise convolution (1x1 convolution) is applied to combine the outputs from the depthwise convolution across all channels.DWSConv reduces computational complexity by separating convolution into depthwise and pointwise operations, maintaining performance in tasks like image classification and object detection, and allowing for more complex architecture design without increasing computational requirements.

- Integration of SCAttn Module: After the depthwise separable convolution, the SCADW block integrates the SCAttn (Same Channel Attention) module. The SCAttn module utilizes global average pooling to extract global features from the output of the depthwise convolution. This process allows the model to focus on the most relevant features without redundantly processing channel-wise information. SCAttn uses global average pooling to extract global features from the depthwise convolution output, improving feature representation. It reduces redundant operations, lowers computational costs, and is compatible with lightweight models, making it ideal for mobile and edge device applications.

- Output: The output of the SCADW block is a feature map that has been enhanced through the attention mechanism, allowing the model to capture important global context while preserving local feature information [45].

4.6. Stage Attention

4.7. Branch Attention

4.8. Stream-1: Original Image Based Feature

4.9. Stream-2: Enhanced Image-Based Feature

4.10. Feature Concatenation and Classification

4.11. Classification and Training Procedure

5. Experimental Result

5.0.1. Environmental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

5.1. Ablation Study

5.2. Performance Accuracy for the PAD2020 Dataset

5.3. Performance Accuracy for the ISIC-2019 Dataset

5.4. Dicussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AlexNet | Alex Krizhevsky’s Network |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DenseNet121 | Densely Connected Network 121 |

| DenseNet201 | Densely Connected Network 201 |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| InceptionResNetV2 | Inception + ResNet Variant 2 |

| InceptionV3 | Inception Variant 3 |

| MobileNetV2 | Mobile Network Variant 2 |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| ResNet50 | Residual Network 50 |

| ResNet50V2 | Residual Network 50 Variant 2 |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VGG16 | Visual Geometry Group 16 |

| Xception | Extreme Inception |

References

- Nawaz, K.; Zanib, A.; Shabir, I.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Mahmood, T.; Rehman, A. Skin cancer detection using dermoscopic images with convolutional neural network. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. Washington (DC): Office of the Surgeon General (US), 2014. Skin Cancer as a Major Public Health Problem, Accessed: 2023-08-22. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK247164/.

- Mazhar, F.; Aslam, N.; Naeem, A.; Ahmad, H.; Fuzail, M.; Imran, M. Enhanced Diagnosis of Skin Cancer from Dermoscopic Images Using Alignment Optimized Convolutional Neural Networks and Grey Wolf Optimization. Journal of Computing Theories and Applications 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.B.; Akbar, S.; ul Ain, Q.; Naqvi, Z.; Urooj, F. Skin Cancer Detection and Classification Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Unbalanced Data: State of the Art. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging 2025, 124–146. [Google Scholar]

- Khullar, V.; Kaur, P.; Gargrish, S.; Mishra, A.M.; Singh, P.; Diwakar, M.; Bijalwan, A.; Gupta, I. Minimal sourced and lightweight federated transfer learning models for skin cancer detection. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.T.P.; Jewel, R.M.; Akter, A. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Automated Skin Cancer Detection: Advancements in Diagnostic Accuracy and AI Integration. The American Journal of Medical Sciences and Pharmaceutical Research 2025, 7, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorathi Jayaseeli, J.; Briskilal, J.; Fancy, C.; Vaitheeshwaran, V.; Patibandla, R.L.; Syed, K.; Swain, A.K. An intelligent framework for skin cancer detection and classification using fusion of Squeeze-Excitation-DenseNet with Metaheuristic-driven ensemble deep learning models. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Khatun, R.; Talukder, M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Uddin, M.A.; Ahamed, M.K.U.; Khraisat, A. An Integrated Deep Learning Model for Skin Cancer Detection Using Hybrid Feature Fusion Technique. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; GholamHosseini, H.; Lindén, M. Advanced Deep Learning Models for Melanoma Diagnosis in Computer-Aided Skin Cancer Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobahi, N.; Alhawsawi, A.M.; Damoom, M.M.; Sengur, A. Extreme Learning Machine-Mixer: An Alternative to Multilayer Perceptron-Mixer and Its Application in Skin Cancer Detection Based on Dermoscopy Images. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin Cancer Facts & Statistics. n.d. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts/ Accessed: 2025-06-13.

- Zhang, B.; Zhou, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Ma, J.; Ma, L. Opportunities and challenges: Classification of skin disease based on deep learning. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2021, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zarzà, I.; de Curtò, J.; Hernández-Orallo, E.; Calafate, C.T. Cascading and Ensemble Techniques in Deep Learning. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loescher, L.J.; Janda, M.; Soyer, H.P.; Shea, K.; Curiel-Lewandrowski, C. Advances in skin cancer early detection and diagnosis. In Proceedings of the Seminars in oncology nursing; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 29, pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, M.; Gilani, S.Q.; Syed, T.; Marques, O.; Kim, H.C. Skin Cancer Detection Using Deep Learning — A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethanan, K.; Pitakaso, R.; Srichok, T.; Khonjun, S.; Thannipat, P.; Wanram, S.; Boonmee, C.; Gonwirat, S.; Enkvetchakul, P.; Kaewta, C.; et al. Double AMIS-ensemble deep learning for skin cancer classification. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 234, 121047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Mamunur Rashid, M.; Redwanur Rahman, M.; Tofayel Hossain, M.; Shahidujjaman Sujon, M.; Nawal, N.; Hasan, M.; Shin, J. Alzheimer’s disease detection using CNN based on effective dimensionality reduction approach. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Computing and Optimization: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Optimization 2020 (ICO 2020). Springer, 2021; pp. 801–811. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.; Musa Miah, A.S.; Shin, J. Residual-Based Multi-Stage Deep Learning Framework for Computer-Aided Alzheimer’s Disease Detection. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Miah, A.S.M.; Hirooka, K.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Maniruzzaman, M. Parkinson Disease Detection Based on In-air Dynamics Feature Extraction and Selection Using Machine Learning. arXiv preprint 2024, arXiv:2412.17849. [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Izquierdo, J.A.; Molina-López, I.; Rodríguez-Lomba, E.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Suarez-Fernandez, R.; Lazaro-Ochaita, P. Who detects melanoma? Impact of detection patterns on characteristics and prognosis of patients with melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2016, 75, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkin, D.; Thomas, A.; Teicher, B.A. Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genetics 2024, 286-287, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dilger, J.P. Different strategies for cancer treatment: Targeting cancer cells or their neighbors? Chinese Journal of Cancer Research 2025, 37, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.M.; Telang, B.; Soni, G.; Khalife, A. Overview of perspectives on cancer, newer therapies, and future directions. Oncology and Translational Medicine 2024, 10, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Celebi, M.E.; Iyatomi, H.; Schaefer, G.; Stoecker, W.V. Lesion border detection in dermoscopy images. Computerized medical imaging and graphics 2009, 33, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruch, F.; Bogo, F.; Bonazza, M.; Cappelleri, V.M.; Peserico, E. Simpler, faster, more accurate melanocytic lesion segmentation through meds. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2013, 61, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; et al. Convolutional Neural Networks: An Overview and Application in Radiology. Insights into Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.M. Theoretical Understanding of Convolutional Neural Network: Concepts, Architectures, Applications, Future Directions. Computation 2023, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, D.; Undavia, J.N. A Comprehensive assessment of Convolutional Neural Networks for skin and oral cancer detection using medical images. Healthcare Analytics 2023, 3, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Qureshi, A.N.; Li, J.; et al. On the Analyses of Medical Images Using Traditional Machine Learning Techniques and Convolutional Neural Networks. Archive of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023, 30, 3173–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Shin, J. Dynamic Hand Gesture Recognition using Multi-Branch Attention Based Graph and General Deep Learning Model. IEEE Access 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapriya, S.; Karuna, Y. Pre-trained deep learning models for brain MRI image classification. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morid, M.A.; Borjali, A.; Del Fiol, G. A scoping review of transfer learning research on medical image analysis using ImageNet. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 128, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.W.; Khan, S.; Gupta, G.; Alabduallah, B.I.; Almjally, A.; Alsolai, H.; Siddiqui, T.; Mellit, A. A Study of CNN and Transfer Learning in Medical Imaging: Advantages, Challenges, Future Scope. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Arefin, M.B.; Akhtar, F.; Blake, J. Combining state-of-the-art pre-trained deep learning models: A noble approach for skin cancer detection using max voting ensemble. Diagnostics 2023, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Shin, J.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Okuyama, Y.; Nobuyoshi, A. Dynamic Hand Gesture Recognition Using Effective Feature Extraction and Attention Based Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Embedded Multicore/Many-core Systems-on-Chip (MCSoC); IEEE, 2023; pp. 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Shin, J.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Nobuyoshi, A. Skeleton-based hand gesture recognition using geometric features and spatio-temporal deep learning approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th European Workshop on Visual Information Processing (EUVIP); IEEE, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Nishimura, S.; Shin, J. Sign Language Recognition using Graph and General Deep Neural Network Based on Large Scale Dataset. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Okuyama, Y.; Tomioka, Y.; Shin, J. Spatial–temporal attention with graph and general neural network-based sign language recognition. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2024, 27, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Bulat, A.; Tan, F.; Zhu, X.; Dudziak, L.; Li, H.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Martinez, B. Edgevits: Competing light-weight cnns on mobile devices with vision transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer, 2022; pp. 294–311. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Musa Miah, A.S.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Hirooka, K.; Suzuki, K.; Lee, H.S.; Jang, S.W. Korean Sign Language Recognition Using Transformer-Based Deep Neural Network. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Miah, A.S.M.; Suzuki, K.; Hirooka, K.; Hasan, M.A.M. Dynamic Korean Sign Language Recognition Using Pose Estimation Based and Attention-Based Neural Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143501–143513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2110.02178. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Liu, R.; Wu, T.; Wang, M.; Yin, J.; Liu, J. Deeply supervised skin lesions diagnosis with stage and branch attention. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Scientific data 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, T.J.; Hekler, A.; Utikal, J.S.; Grabe, N.; Schadendorf, D.; Klode, J.; Berking, C.; Steeb, T.; Enk, A.H.; Von Kalle, C. Skin cancer classification using convolutional neural networks: systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research 2018, 20, e11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, K.; Turki, T. Automatic Classification of Melanoma Skin Cancer with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. AI 2022, 3, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Fatemi, M.I.; Khan, M.M.; Kaur, M.; Zaguia, A. Comparative Analysis of Skin Cancer (Benign vs. Malignant) Detection Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2021, 2021, Article ID 5895156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaha, H.; Hassan, A. Skin cancer diagnosis based on deep transfer learning and sparrow search algorithm. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 815–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, W.; Park, G.H.; Park, I.; Chang, S.E. Classification of the clinical images for benign and malignant cutaneous tumors using a deep learning algorithm. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2018, 138, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.C.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 international symposium on biomedical imaging (isbi), hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (isic). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2018); IEEE, 2018; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, D.; Codella, N.C.; Celebi, E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.; Mishra, N.; Halpern, A. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) 2016, hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). arXiv preprint, 2016; arXiv:1605.01397. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, C.; Celebi, M.E.; Marques, J.S. Improving dermoscopy image classification using color constancy. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2014, 19, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Sahinbas, K.; Catak, F.O. Transfer learning-based convolutional neural network for COVID-19 detection with X-ray images. In Data science for COVID-19; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, M.; Knackstedt, T.; Yan, S.; Hassanpour, S. Artificial intelligence-based image classification methods for diagnosis of skin cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Computers in biology and medicine 2020, 127, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dildar, M.; Akram, S.; Irfan, M.; Khan, H.U.; Ramzan, M.; Mahmood, A.R.; Alsaiari, S.A.; Saeed, A.H.M.; Alraddadi, M.O.; Mahnashi, M.H. Skin cancer detection: a review using deep learning techniques. International Journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, B.; Jun, S.; Palade, V.; You, Q.; Mao, L.; Zhongjie, M. Improving Skin Cancer Classification Using Heavy-Tailed Student T-Distribution in Generative Adversarial Networks (TED-GAN). Diagnostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, H.; Tanveer, M.A.; Aqeel Khan, H. Skin Lesion Classification Using GAN based Data Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2019; pp. 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rasheed, A.; Ksibi, A.; Ayadi, M.; Alzahrani, A.I.A.; Elahi, M.M. An Ensemble of Transfer Learning Models for the Prediction of Skin Lesions with Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging 2023, 2023, Article ID 5869513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebaili, A.; Lapuyade-Lahorgue, J.; Ruan, S. Deep Learning Approaches for Data Augmentation in Medical Imaging: A Review. Journal of Imaging 2023, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV); 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alexey, D. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, D.P.; Ji, G.P.; Zhou, T.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Pranet: Parallel reverse attention network for polyp segmentation. In Proceedings of the International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention; Springer, 2020; pp. 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Wang, W.; Shen, J.; Crandall, D.; Luo, J. Zero-shot video object segmentation with co-attention siamese networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 44, 2228–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiß, S.; Seibold, C.; Freytag, A.; Rodner, E.; Stiefelhagen, R. Every annotation counts: Multi-label deep supervision for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2021; pp. 9532–9542. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, X.; Lu, X.; Khan, F.S.; Hoi, S. Distilled Siamese networks for visual tracking. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 44, 8896–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, J.; Song, M. Spot-adaptive knowledge distillation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 3359–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV); 2018; pp. 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Chen, B.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Le, Q.V. Mnasnet: Platform-aware neural architecture search for mobile. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2019; pp. 2820–2828. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision; 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanwimolkul, S.; Komorita, S. Efficient linear attention for fast and accurate keypoint matching. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 international conference on multimedia retrieval; 2022; pp. 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Z.; Lin, Z.; Yuille, A. Lite vision transformer with enhanced self-attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2022; pp. 11998–12008. [Google Scholar]

- Gessert, N.; Nielsen, M.; Shaikh, M.; Werner, R.; Schlaefer, A. Skin lesion classification using ensembles of multi-resolution EfficientNets with meta data. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Ishfaq, M.; Ali, G.; Saeed, M.R.; Hussain, M.; Alkhalifah, T.; Alturise, F.; Samand, N. Skin cancer disease detection using transfer learning technique. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combalia, M.; Codella, N.C.; Rotemberg, V.; Helba, B.; Vilaplana, V.; Reiter, O.; Carrera, C.; Barreiro, A.; Halpern, A.C.; Puig, S.; et al. Bcn20000: Dermoscopic lesions in the wild. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1908.02288. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, A.G.; Lima, G.R.; Salomao, A.S.; Krohling, B.; Biral, I.P.; de Angelo, G.G.; Alves Jr, F.C.; Esgario, J.G.; Simora, A.C.; Castro, P.B.; et al. PAD-UFES-20: A skin lesion dataset composed of patient data and clinical images collected from smartphones. Data in brief 2020, 32, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV Team. Image Thresholding — OpenCV-Python Tutorials 1 documentation. 2024. https://docs.opencv.org/4.x/d7/d4d/tutorial_py_thresholding.html Accessed: 2025-06-20.

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural networks 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.R.; Martinez, T.; Giraud-Carrier, C. An instance level analysis of data complexity. Machine learning 2014, 95, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Alqahtani, F.; Tolba, A. A transformer-BERT integrated model-based automatic conversation method under English context. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 55757–55767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Hassan, N.; Bhatti, N.; Zia, M.; Shin, J. White balancing based improved nighttime image dehazing. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Ullah, S.; Bhatti, N.; Mahmood, H.; Zia, M. A cascaded approach for image defogging based on physical and enhancement models. Signal, image and video processing 2020, 14, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Ullah, S.; Bhatti, N.; Mahmood, H.; Zia, M. The Retinex based improved underwater image enhancement. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 1839–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Miah, A.S.M.; Suzuki, T.; Shin, J. Gradual Variation-Based Dual-Stream Deep Learning for Spatial Feature Enhancement with Dimensionality Reduction in Early Alzheimer’s Disease Detection. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderveld, K. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. Graphics gems IV, 1994; 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, L.S.; Hwang, S.H. An advanced contrast enhancement using partially overlapped sub-block histogram equalization. IEEE transactions on circuits and systems for video technology 2001, 11, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, R.; Ma, K. Contrastive deep supervision. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gollapudi, S. Learn computer vision using OpenCV; Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dozat, T. Incorporating Nesterov Momentum into Adam. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, Workshop Track; 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Inthiyaz, S.; Altahan, B.R.; Ahammad, S.H.; Rajesh, V.; Kalangi, R.R.; Smirani, L.K.; Hossain, M.A.; Rashed, A.N.Z. Skin Disease Detection Using Deep Learning. Advances in Engineering Software 2023, 175, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakid, G.; Gouda, W.; Humayun, M.; Sama, N.U. Melanoma Detection Using Deep Learning-Based Classifications. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, K.; Turki, T. Automatic Classification of Melanoma Skin Cancer with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Ai 2022, 3, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechelli, S.; Delhommelle, J. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Skin Cancer Classification from Dermoscopic Images. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Yilmaz, F.; Kose, O. Early Detection of Skin Cancer Using Deep Learning Architectures: ResNet-101 and Inception-v3. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO), Izmir, Turkey, October 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kaggle competitions. SIIM-ISIC Melanoma Classification. SIC 2018 - Winners Final 3 Submissions, 2020. SIIM-ISIC Melanoma Classification-Identify melanoma in lesion images. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/siim-isic-melanoma-classification/discussion/173086w Accessed: 2023-08-22.

- Gouda, W.; Sama, N.U.; Al-Waakid, G.; Humayun, M.; Jhanjhi, N.Z. Detection of Skin Cancer Based on Skin Lesion Images Using Deep Learning. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ablation Study | Augmentation Models | Stream-1 | Stream-2 | PAD2020 (Accuracy %) | ISIC-2019 (Accuracy %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Stream | First Augmentation → Then Splitting train-test | Stream-1 | - | 94.22 | 82.00 |

| Dual Stream | First Splitting train-test → Then Augmentation only on train set | Stream-1 | Stream-2 | 70.00 | 62.65 |

| Proposed Dual Stream | First Augmentation → Then Splitting train-test | Stream-1 | Stream-2 | 98.59 | 83.00 (Average), 88.62 (Best Fold) |

| K-Fold | BestAccuracy | BestRecall | BestSpecificity | BestPrecision | BestF1Score |

| val_1 | 98.31 | 78.68 | 99.66 | 79.13 | 78.90 |

| val_2 | 98.55 | 79.57 | 99.71 | 79.44 | 79.50 |

| val_3 | 98.54 | 79.20 | 99.70 | 80.19 | 79.67 |

| val_4 | 98.87 | 79.64 | 99.76 | 81.40 | 80.44 |

| val_5 | 98.68 | 79.68 | 99.73 | 80.18 | 79.92 |

| val_6 | 98.49 | 79.33 | 99.69 | 79.99 | 79.65 |

| val_7 | 98.27 | 78.81 | 99.64 | 79.33 | 79.06 |

| val_8 | 99.02 | 80.69 | 99.78 | 81.85 | 81.24 |

| val_9 | 98.76 | 80.48 | 99.75 | 80.24 | 80.35 |

| val_10 | 98.38 | 78.30 | 99.66 | 80.09 | 79.11 |

| Average | 98.59 | 79.44 | 99.71 | 80.18 | 79.78 |

| Reference | Published Year | Methodology | Dataset | Performance Accuracy [%] |

| VGG16 | VGG16 | PAD2020 | 70.83% | |

| ResNet101 | ResNet101 | PAD2020 | 90.67% | |

| MobileNetV2 | MobileNetV2 | PAD2020 | 91.44% | |

| MobileViT_s | MobileViT_s | PAD2020 | 89.22% | |

| MobileNetV3L | MobileNetV3L | PAD2020 | 91.78% | |

| ShuffleNetV2_1.× | ShuffleNetV2_1.× | PAD2020 | 91.89% | |

| RegNetY6.4gf | RegNetY6.4gf | PAD2020 | 90.67% | |

| MnasNet1.0 | MnasNet1.0 | PAD2020 | 91.33% | |

| EfficientNet_b0 | EfficientNet_b0 | PAD2020 | 91.13% | |

| Ensembled Model | Ensembled Model | PAD2020 | 94.11% | |

| HierAttn_xs [45] | 2024 | HierAttn_xs | PAD2020 | 90.11% |

| HierAttn_s [45] | 2024 | HierAttn_s | PAD2020 | 91.22% |

| Proposed Method | - | Two Stream Model | PAD2020 | 98.59% |

| K-Fold | BestAccuracy | BestRecall | BestSpecificity | BestPrecision | BestF1Score |

| val_1 | 83.44 | 83.29 | 97.64 | 83.49 | 83.34 |

| val_2 | 87.65 | 87.54 | 98.24 | 87.65 | 87.49 |

| val_3 | 79.85 | 79.64 | 97.12 | 79.80 | 79.49 |

| val_4 | 81.84 | 81.71 | 97.41 | 82.14 | 81.82 |

| val_5 | 84.14 | 84.01 | 97.73 | 84.48 | 84.08 |

| val_6 | 77.49 | 77.23 | 96.79 | 77.78 | 77.35 |

| val_7 | 82.49 | 82.37 | 97.50 | 82.31 | 82.22 |

| val_8 | 88.63 | 88.55 | 98.37 | 88.94 | 88.60 |

| val_9 | 86.25 | 86.02 | 98.04 | 86.45 | 86.14 |

| val_10 | 78.69 | 77.55 | 96.97 | 78.01 | 77.66 |

| Average | 83.05 | 82.79 | 97.58 | 83.11 | 82.82 |

| Authors and Paper | Dataset | Model | Published Year | Performance Accuracy with for first splitting then Augmentation only training set | Performance Accuracy with for the first augmentation then splitting their training and testing set | Specificity |

| Inthiyaz et al. [97] | Xiangya-Derm | CNN | 2023 | - | AUC = 0.87 | - |

| Alwakid et al. [98] | HAM10000 | CNN, ResNet50 | 2023 | - | F1-score = 0.859 (CNN), 0.852 (ResNet50) | - |

| Aljohani and Turki [99] | ISIC 2019 | Xception, DenseNet201, ResNet50V2, MobileNetV2, VGG16, VGG19, and GoogleNet | 2022 | - | Accuracy = 76.09% | - |

| Bechelli and Delhommelle [100] | HAM10000 | CNN, VGG16, Xception, ResNet50 | 2022 | - | Accuracy = 88% (VGG16) | - |

| Demir et al. [101] | ISIC archive | ResNet101 and InceptionV3 | 2019 | - | F1-score = 84.09% (ResNet101), 87.42% (InceptionV3) | - |

| Kaggle Compt. [102] | ISIC2018 | Top 10 model Average | 2020 | - | Accuracy = 86.7% | - |

| Gouda et al. [103] | ISIC 2018 | CNN | 2022 | 62.50 | Accuracy = 83.2% | - |

| Proposed Model | ISIC 2018 | Duel Strem | - | 62.65(Best Fold) | Accuracy = 88.62% (Best Fold) | 98.37 (Best Fold) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).