1. Introduction

The question of the nature of health is one of the fundamental, but surprisingly underdetermined challenges of the human sciences. Despite an inflationary use of the term in medical, psychological, social and political discourses, the definition of health often remains diffuse, contradictory or ideologically overlaid (Saracci, 1997; Nordenfelt, 2007). The classic formula of the World Health Organization (WHO) that health is "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being" (WHO, 1948) has on the one hand broadened the horizon beyond the purely biomedical view, but on the other hand has attracted massive criticism – especially because of its utopia, its immeasurability and its ignorance of the processual nature of human life (Huber et al., 2011).

Modern health research has therefore begun to develop alternative concepts that understand health not as a static state, but as a dynamic, systemically contextualized ability to adapt (Jull et al., 2017; Frank, 2013). These approaches include, for example, Antonovsky's (1987) Salutogenesis model, which emphasizes the resistance resources in dealing with stressors, or Engel's biopsychosocial model (1977), which understands the human being in his somatic, psychological and social complexity. These integrative models are groundbreaking, but they often remain flat in their hierarchical differentiation of functional health levels and largely ignore deep anthropological dimensions – such as meaning, purposefulness and generativity (Frankl, 1985; Cloninger, 2004). Out of this diagnostic gap, the present article proposes a new model: the homeodynamic health model according to Pazer. It is based on the assumption that health is a graded, adaptive and teleologically oriented process that ranges from mere survival to the generative transmission of life. The theory draws on systems theoretical, developmental psychology and existential philosophical perspectives and understands health as a multidimensional ability for inner integration, functional self-regulation and meaning-related transcendence (Canguilhem, 1991; McEwen, 2007; Ryff & Singer, 1998).

The term homeodynamics, in contrast to classical homeostasis (Cannon, 1932), does not describe a fixed setpoint, but a flexible equilibrium within an open, adaptable system (Selye, 1956; Bernard, 1865/1974). Health is thus not defined as a static optimum, but as a dynamic continuum between dysfunction, resilience and excellence – a process that can be realized at different levels and characterized by specific physiological, psychological and existential characteristics.

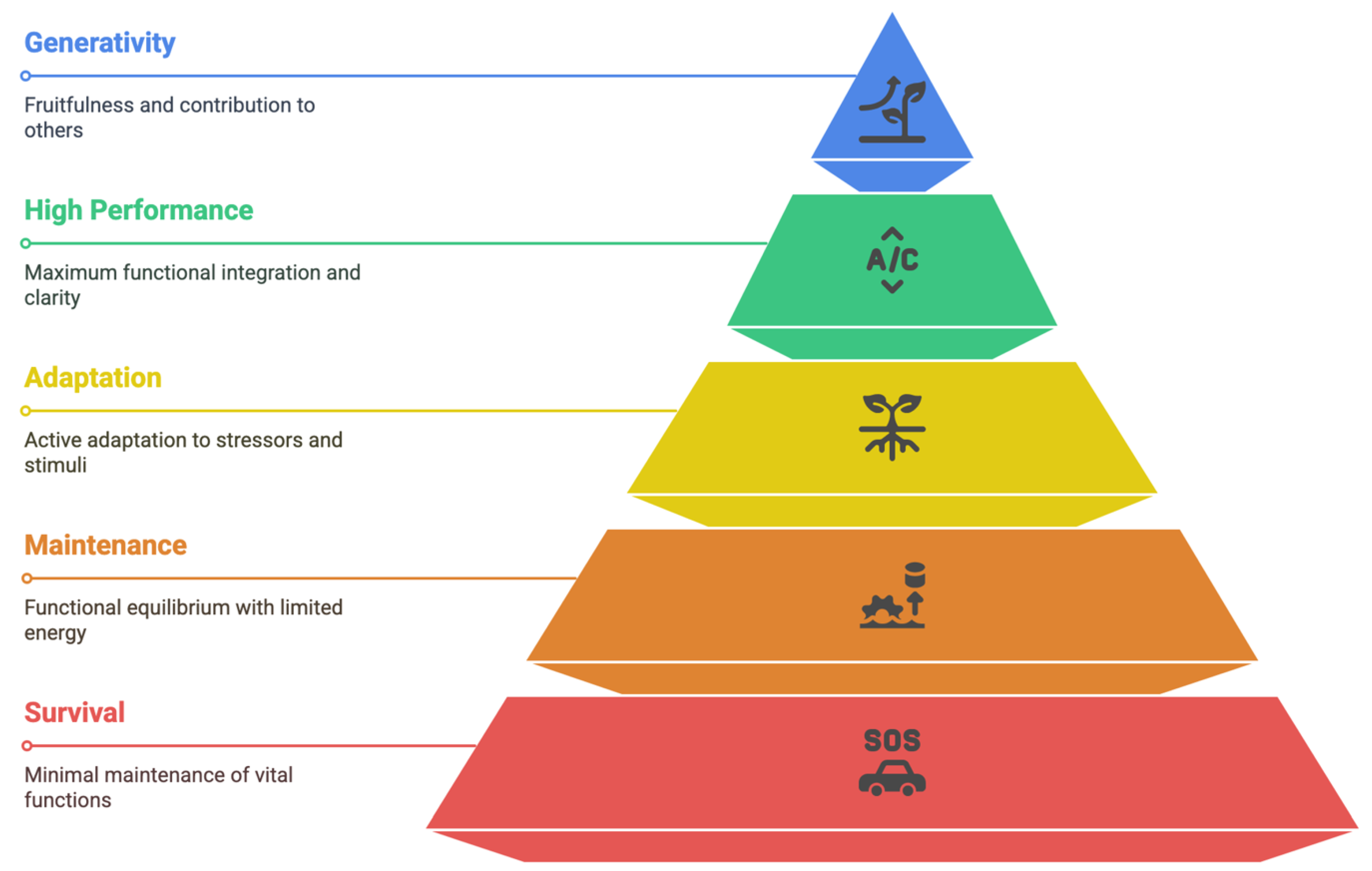

The aim of this article is to develop the homeodynamic health model in five clearly distinguishable phases: (1) survival, (2) preservation, (3) adaptation, (4) high performance and (5) generativity. Each stage is functionally, systemically and anthropologically justified and placed in the context of existing health concepts. The model is intended to be both theoretically sound and practically compatible – for medicine, psychology, social sciences and public health. The hope is that this systematization will open up a more differentiated and realistic approach to the question of health – as a dynamic field of tension between biological vitality, psychological coherence and existential fertility.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Health Between Homeostasis and Dynamics

The history of modern medicine is inextricably linked to the concept of homeostasis – the classical equilibrium principle that has been considered the basis of physiological stability since Claude Bernard (1865/1974) and Walter B. Cannon (1932). In this perspective, the organism is considered a self-regulating system that strives to correct deviations from an internal target value. This view is still deeply rooted in clinical practice today – especially in intensive care, endocrinology and circulatory regulation. But this model is coming under increasing pressure: because it ignores the fact that living systems are in constant interaction with a changing environment. An organism that only remains stable would be incapable of adaptation, development and resilience at the same time. In response to this deficit, the concept of homeodynamics was developed (Selye, 1956; McEwen, 2007), which no longer focuses on rigid equilibria but on dynamic regulatory processes. A person's health does not consist in remaining stable, but in successfully and functionally adapting to changing internal and external conditions – i.e. going through equilibriums, not preserving them (Goldstein, 1995). Especially in today's time of chronic stress, uncertain environmental conditions and complex stressors, this dynamic understanding of health is becoming increasingly important. The human being is not a thermostat, but an adaptive, plastic, open system. Health is thus no longer the opposite of illness, but an expression of the ability to regulate under conditions of complexity, ambiguity and stress.

2.2. Salutogenesis: The Human Being as an Adaptive System

Aaron Antonovsky (1987) made a paradigmatic break with the deficit perspective of classical pathogenesis with his model of salutogenesis. Health is not understood here as a goal, but as a process on a continuum between "health" and "disease". Central to this is the sense of coherence – the feeling of understandability, manageability and meaningfulness of life. The stronger this sense of coherence, the higher the ability to deal with stressors and stay healthy.

As valuable as this change of perspective is, it takes little account of how strong an individual actually is in his or her ability to function. The sense of coherence is subjective, not objectifiable – and says nothing about whether a person is merely stabilized or lives in a state of vitality, resilience or generative development. There is a lack of a functional hierarchy.

This is where the homeodynamic health model comes in: it takes up the dynamic salutogenesis approach, but complements it with a structured, hierarchically differentiated logic of human adaptivity. It's not just about whether a person can deal with stress, but how profoundly, creatively and fruitfully they do so – in other words, with what degree of inner integration.

2.3. Biopsychosocial Model and System Perspective

Another conceptual point of reference is the biopsychosocial model by George L. Engel (1977), which understands the human being as a networked unity of body, psyche and social context. It breaks with the reductionist logic of the biomedical model by recognizing psychological, emotional, and interpersonal factors as integral parts of health development. Since then, this model has been widely used in psychosomatic medicine, health psychology and social work (Borrell-Carrió, Suchman & Epstein, 2004).

Nevertheless, this model also usually remains structurally indifferent: it recognizes the multidimensionality of health, but does not arrange it along a developmental framework. The question of what functional state a person is in within this biopsychosocial system – acutely vitally endangered, functionally stabilized, adaptively resilient or even generatively active – remains open.

The homeodynamic health model sees itself as a further development of this perspective: it integrates biopsychosocial complexity into a dynamic developmental logic that comprises five clearly distinguishable phases. The focus is on the functional level and lifespan of a person, not just on his or her stress situation.

2.4. Anthropological Depth Dimensions of Health

While medicine is usually focused on the functional or organic level of the human being, philosophical anthropology opens up a deeper perspective: health is not only a physical or psychological state, but an expression of a successful human existence (Frankl, 1985; Jonas, 1984). Viktor Frankl (1985), for example, saw the human ability to make sense as the center of his health: "Not lust, not power, but meaning is the primary motivating force" (p. 52). A person who experiences his existence as meaningful not only has a higher resilience to illness, but also reaches deeper levels of viability.

The concept of generativity (Erikson, 1980; McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992) plays a central role in the later phase of the health model: the ability to have an impact beyond one's own life – through reproduction, education, cultural creation or spiritual transmission – is a highly demanding expression of health. It requires a high degree of inner integration, psychological stability and functional vitality.

3. The Homeodynamic Health Model According to Pazer

The homeodynamic health model according to Pazer understands health as a processual, multidimensional unfolding of viability. In the tradition of systems theory and developmental psychology approaches, it conceives of health not as a binary state (healthy vs. sick), but as a hierarchical continuum of functional organization in an open, adaptive organism. The five proposed stages – survival, preservation, adaptation, high performance and generativity – describe qualitatively different modes of physical, psychological and existential self-regulation. They can be used both retrospective-diagnostic and prospective-therapeutic.

3.1. Phase 1: Survival (Emergency Mode)

The first stage is characterized by the minimal preservation of vital functions . The organism is in emergency mode – all energy is focused on securing the absolute foundations of life. From a homeodynamic point of view, the system is severely limited, but has not yet collapsed; it tries to enforce stability through emergency programs (e.g., catecholamine release, cortisol flooding, centralization of blood flow) (McEwen, 2007; Goldstein, 1995). Psychologically, this phase is often characterized by acute fear, panic or dissociation . The ability to think reflectively, to form social relationships or to express oneself emotionally is greatly reduced – the repertoire is limited to primitive protective mechanisms (Porges, 2011; van der Kolk, 2014). Existentially, those affected often experience a state of being at the mercy of others in this phase, of alienation from themselves and the world. This phase clinically corresponds to conditions such as shock, trauma, severe hypoglycemia, panic attacks, suicidal tendencies or acute depression.

3.2. Phase 2: Conservation (Stability Mode)

After acute emergency reactions have subsided, the organism can stabilize itself into a functional but precarious state of equilibrium. The system is no longer at risk of imminent collapse, but it still has limited energy and regulatory capacity. Characteristic is a chronic activation of stress axes (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), coupled with immunological weakness and metabolic instability (Chrousos, 2009). Psychologically, this phase manifests itself in lack of drive, reduced motivation, emotional irritability or withdrawal tendencies. Self-regulation is unstable: neither emotional resilience nor cognitive flexibility are fully available. Everyday life can often only be managed through routine and externally structured framework conditions (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Existentially, this phase is characterized by a lack of reference to meaning and the future. People live "from day to day", without an inner mission or overarching orientation – a state that Frankl (1985) described as an "existential vacuum".

3.3. Phase 3: Adaptation (Aufbaumodus)

In this phase, the organism develops the ability to actively adapt to stress and stimuli – both in the physiological and psychological sense. Homeodynamically, one speaks of an expansion of the range of adaptations: the organism can now not only react to changes, but also generate functional improvement from them (Selye, 1956; Sterling & Eyer, 1988). Physically, this means increased trainability, regenerative ability and system plasticity: heart rate variability, sleep quality, hormonal cycles and muscle building improve. The immune system reacts appropriately instead of excessively.

Psychologically, self-efficacy, creativity and motivation are now accessible again. Humans develop resources for emotional regulation, goal pursuit and social integration. Autonomy and competence are experienced subjectively – a state that self-determination theory describes as the basis of psychological well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Existentially, a conscious reference to meaning often occurs here for the first time: the question of "what for" is no longer fended off, but motivating. People begin to shape their lives instead of just surviving them.

3.4. Phase 4: High Performance (Peak Mode)

The fourth phase describes a state of maximum functional integration. The organism is able to operate at a high level – with high stress tolerance and flexible self-regulation at the same time. This applies not only to physical performance (e.g. VO2 max, muscle strength, responsiveness), but also to mental clarity, emotional depth and social effectiveness. Neurobiologically, this phase is associated with flow states, i.e. an optimal fit between requirement and ability (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Cortisol, dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin are in a balanced interplay – a state that modern neuroecology calls the "harmonious brain state" (Dietrich & Kanso, 2010). Psychologically, there is a high degree of coherence, goal orientation and creativity. People in this phase no longer act reactively, but proactively – they create, lead, teach. Affect regulation is also at a maximum level: emotions are not disturbing, but functionally integrated into self-control and interpersonal resonance. Existentially, the space for transcendent self-transcendence opens up in this phase. Man becomes a medium of something greater: responsibility, truth, vocation. Frankl (1985) speaks here of "self-transcendence as the essence of being human".

3.5. Phase 5: Generativity

The highest level in the homeodynamic health model is not performance, but fertility. Man becomes a source for others – biologically, spiritually, socially, culturally. Generativity, as Erikson (1980) described it, is the will to let one's own self survive, through children, works, values, or institutional design. Physiologically, generativity manifests itself in stable reproductive capacity, hormonal coherence (e.g., estrogen-testosterone balance), immunological robustness, and energetic sustainability. The aging process is also often slowed down or consciously shaped in this phase (Loeckenhoff & Cartensen, 2004). Psychologically, generativity is associated with empathy, care, responsibility, and vision. Man no longer lives primarily for himself, but in relation to a greater whole. This corresponds to the ability to empathize with others, to lead, to serve – without burning out.

Existentially, this phase is characterized by a deep sense of meaning. The question of the "why" of one's own life is no longer sought, but lived. Health here means: being able to understand one's own life as a contribution to the lives of others.

4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The homeodynamic health model according to Pazer unfolds its value not only on the level of theoretical systematics, but above all through its praxeological connectivity. By understanding health as a step-by-step hierarchy of functional and existential integration, it offers a differentiating instrument for analyzing, promoting and accompanying human development – in medicine, psychotherapy, public health, coaching and pastoral care in equal measure. In the following, three central implication axes of the model will be outlined: diagnostic depth sharpening, step-based intervention logic and interdisciplinary connectivity.

4.1. Diagnostic Depth Sharpening

Common health diagnostics – both in the medical and psychological fields – usually operate along categorical dichotomies: healthy vs. sick, functional vs. dysfunctional, symptom-free vs. in need of treatment. However, such binary models are only suitable to a limited extent for precisely capturing the functional state of a person in the context of his or her reality of life (Boorse, 1977; Huber et al., 2011). The homeodynamic model allows for fine-grained functional differentiation, in which not only symptoms but also the quality, depth and range of viability can be assessed. Two people with the same blood count or psychometric score can be at completely different levels of the health continuum – one in stabilized maintenance mode, the other in adaptive self-efficacy. For example, the diagnosis of a "mild depressive episode" (ICD-10: F32.0) in the Pazer model can correspond to either the second stage (maintenance) or the third stage (adaptation) – depending on whether it is a reactive overload or a developmental transitional state. This opens up a new form of functional diagnostics that not only records what, but also where a condition develops – prognostically instead of just descriptively.

4.2. Step-Based Intervention Logic

The model also opens up a developmental perspective on therapy, training and support, which reacts dynamically to the respective state of health. Instead of using "health-promoting measures" across the board, a distinction can be made: Which intervention fits the current phase – and which goal is realistically achievable?

Examples of interventions appropriate to the stage:

Phase 1 (survival): stabilization, emergency intervention, protection. No change work. Focus: Safety and vital function.

Phase 2 (maintenance): Rhythm, structure, basic health (sleep, nutrition, stress reduction). Goal: sustainable resilience.

Phase 3 (Adaptation): Training, coaching, target work, resource activation. Goal: Strengthening self-regulation and resilience.

Phase 4 (High Performance): Peak Performance, Flow Promotion, Leadership Coaching. Goal: effectiveness and personal excellence.

Phase 5 (Generativity): Mentoring, Parenting, Vocation, Ethics. Goal: Passing on life, value orientation, integration.

This logic makes it possible to avoid being overwhelmed and at the same time to promote targeted development. It is in line with processual approaches of developmental psychology (Lerner et al., 2005) and systemic therapy (Simon, 2006), but complements them with an explicit hierarchical order of functional levels.

4.3. Interdisciplinary Connectivity

The homeodynamic health model can be connected to central discourses of different disciplines:

In medicine , it complements the pathophysiology with a positive functional analysis that goes beyond pure organ values.

In psychotherapy , it offers a development-oriented framework model that interprets symptoms in the context of human development.

In public health , it can help to make prevention and health promotion more specific to the target group – e.g. through level-specific programmes in schools, communities or companies.

In theology and anthropology , it integrates the meaning of human existence as a health dimension and opens up the space for ethically founded health concepts, such as those indicated in the ethics of care (Tronto, 1993) or in Viktor Frankl's existential analysis (1985).

Due to this connectivity, the model has the potential to build bridges between scientific, psychological and human science interpretations of health – something that current models only provide fragmentarily.

5. Discussion and Outlook

The homeodynamic health model according to Pazer claims to describe health as a dynamic ability for inner self-regulation, functional adaptation and existential development. In contrast to traditional state models, it postulates a hierarchically structured developmental logic that takes the human being seriously as a body-soul-spiritual system and integrates physiological as well as psychological and anthropological dimensions. This chapter discusses the model in the light of existing theoretical landscapes, examines its epistemological implications, identifies critical methodological questions and outlines perspectives for research and application.

5.1. Ontological Deep Structure: Health as a Scalable Viability

For decades, health research has been dominated by a shortened concept of health, which occurs either pathological-reductionist (in the sense of biomedicine) or subject-centered-functionalist (in the sense of the WHO definition or the wellbeing paradigm). What both strands have in common is that they largely dispense with a systematic hierarchy of functional life performances. This is exactly where the present model comes in: It understands health as scalable viability in the sense of a gradual increase in complexity integration and effectiveness in life. From an ontological point of view, the human being is not only a surviving organism system, but a transcending being that – in the language of Viktor Frankl – is capable of realizing meaning (Frankl, 1985). Accordingly, health is understood not only as coherence under stress, as in salutogenesis (Antonovsky, 1987), but as a gradual differentiation of abilities that aim beyond mere existence to a generative, creative form of existence. The structural logic of the model can therefore be thought of as a teleological order: from survival to meaning.

It should be emphasized that the model does not appear normativist in the moral sense, but structurally theoretical: it distinguishes between different qualities of viability without deriving moral value judgments from them. Someone in phase 1 is not "worth less" than someone in phase 4 or 5 – but they are limited in their ability to self-regulate and create. The model recognizes the intrinsic value of each person, but differentiates their functional degrees of development.

5.2. Systematic Classification: Difference and Connectivity

Compared to existing health concepts, the Pazer model has a double quality: it is both connectable and differentiating. Thus, it adopts from the biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977) the basic assumption that health represents a multidimensional reality that includes biological, psychological and social aspects. At the same time, it transcends this model by ordering the horizontal levels vertically: not only what is integrated is decisive, but at what level this integration takes place.

The situation is similar with Antonovsky's salutogenesis: the continuum between health and illness is expanded here by a functional deep structure that can analyze not only where someone stands on the continuum, but also how complex, adaptive and generative his or her way of life is. Although the sense of coherence is still relevant in this model, it is supplemented by objectifiable markers such as stress tolerance, degree of self-control, emotional depth and social fertility. Unlike the 1948 WHO definition, which defines health as a state of complete well-being, the Pazer model does not understand health as an ideal state, but as an open developmental structure. A person can already be considered "functionally healthy" at level 2 (preservation), even if he feels neither joy nor meaning - but the path to development remains open to him. In this way, the model eludes both the dogma of standardised perfection and the arbitrariness of subjective self-interpretation.

5.3. Methodological Reflection: Between Typology and Empiricism

The aim of the model is not to create a universally measurable index for health, but to develop a structurally valid typology that can serve as a heuristic order. The model thus joins a tradition of structuring theories such as Piaget's developmental stages, Erikson's psychosocial phases or Maslow's hierarchy of needs. What they all have in common is that they are not directly measurable, but plausible – through observation, qualitative analysis and contextualised interpretation. The biggest methodological challenge lies in operationalization: How can valid indicators be identified with reasonable effort that help to classify the functional health status of a person in the sense of the model? Initial suggestions could be to develop a combination of physiological (e.g. sleep quality, hormone profiles, heart rate variability), psychological (e.g. affective stability, self-efficacy experience, goal orientation) and existential (e.g. meaning construction, generativity, connectedness) markers for each stage.

Empirically, the model would be suitable for an exploratory mixed-methods study with depth psychological interviews, narrative health trajectories and standardized instruments on quality of life. Not only the current state would be relevant, but also transition dynamics – for example: Which interventions enable the leap from stage 2 to stage 3? What resources are constitutive of level 5?

A possible research design could be a longitudinal cohort study with qualitative grounded theory and quantitative physiological correlates – for example among chronically ill people, executives or spiritually engaged people. The aim would be a theoretical saturation of the phase boundaries, as well as a first validation of the structural hypothesis.

5.4. Perspectives for Practice and Interdisciplinary Development

In application, the model opens up several innovation potentials:

First, in clinical practice: Instead of relying solely on diagnostic criteria, the model could help to meet patients individually where they are systemically – i.e. not only in terms of their symptoms, but also in terms of their ability to develop. A person in the maintenance stage needs different interventions than someone in the adaptive phase. Psychosomatic rehabilitation programs, pain therapy or depression treatment could become more differentiated through step-based targeting.

Secondly, in prevention and public health: the division of the population into stage-related health clusters (e.g. resilient – unstable – generative) could help to develop more precise measures: from basic health to self-management to resource activation. The model thus offers a developmentally logically staggered intervention logic that goes beyond target group segmentation.

Thirdly, in educational work, pastoral care and personal development: The model is suitable for enabling people to gain a deep understanding of their own inner dynamics. It can form the basis for psychoeducational programs, spiritual mentoring or integrative coaching methods that aim to make people not only more "functional" but more viable .

In the long term, the model also offers the opportunity to develop an integrative health ethics that sees the good not in the state, but in the ability to develop. It thus combines individual diagnostic depth with a cultural anthropological horizon – and contributes to the question of what it means to live healthily as a human being.

6. Conclusions

The homeodynamic health model according to Pazer formulates a novel approach to the conceptual determination of human health as a dynamically graded ability to self-regulate, adapt and realize meaning. It thus consciously opposes static, dichotomous or purely subject-centered concepts of health and instead proposes a hierarchical order that functionally integrates biological, psychological and existential dimensions. The model focuses on five stages of development – survival, conservation, adaptation, high performance and generativity – which are not understood as a normative evaluation, but as a structural description of increasing viability. In this context, health is interpreted as a process of deepened coherence: a process in which people not only stabilize themselves, but are increasingly able to connect with themselves, their environment and their meaning of existence and become effective.

The model is compatible with existing concepts such as salutogenesis, the biopsychosocial model and anthropological understandings of health, but differs in its explicit vertical structuring and the integration of a generative-meaningful target level. It enables differentiated diagnostics, step-by-step intervention strategies and interdisciplinary applications in medicine, psychotherapy, public health, coaching and pastoral care. At the same time, the model faces methodological challenges: it requires theoretical condensation, empirical exploration and pragmatic translation. In its current form, it is a typological heuristic – but it is precisely in this openness that its strength lies: it invites us to describe health not only as a state, but as a living, tense movement between threat, function, excellence and fertility. At a time when health is increasingly becoming an object of technical control, economic exploitation and individual self-optimization, this model offers an alternative perspective: It is reminiscent of the originally humanistic ideal of medicine – not only to preserve life, but to make it viable.

References

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well; Jossey-Bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, C. Lessons on the Phenomena of Life Common to Animals and Plants; J. Vrin, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Boorse, C. Health as a theoretical concept. Philosophy of Science 1977, 44(4), 542–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell-Carrió, F., Suchman, A. L., & Epstein, R. M. (2004). The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Annals of Family Medicine, 2(6), 576–582. [CrossRef]

- Canguilhem, G. (1991). The normal and the pathological (C. R. Fawcett, Trans.). Zone Books. (Original work published 1966).

- Chrousos, G. P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 5(7), 374–381. [CrossRef]

- Cloninger, C. R. Feeling good: The science of well-being; Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience; Harper & Row, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, A., & Kanso, R. (2010). A review of EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies of creativity and insight. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 822–848. [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. W. W. Norton.

- Frank, A. W. (2013). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1985). The unheard cry for meaning: Psychotherapy and humanism. Simon & Schuster.

- Goldstein, D. S. Goldstein, D. S. (1995). Stress, catecholamines, and cardiovascular disease. Oxford University Press.

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., Horst, H. V. D., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., Leonard, B., Lorig, K., Loureiro, M. I., van der Meer, J. W., Schnabel, P., Smith, R., van Weel, C., & Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ, 343, d4163. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, H. (1984). The imperative of responsibility: In search of an ethics for the technological age. University of Chicago Press.

- Jull, J., Giles, A., & Graham, I. D. (2017). Community-based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: Advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implementation Science, 12, Article 150. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., Freund, A. M., De Stefanis, I., & Habermas, T. (2005). Understanding developmental regulation in adolescence: The use of the Selection, Optimization, and Compensation model. Human Development, 48(6), 326–349. [CrossRef]

- Loeckenhoff, C. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1395–1424. [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D. P., & de St. Aubin, E. (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(6), 1003–1015. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904. [CrossRef]

- Nordenfelt, L. (2007). The concept of health and illness revisited. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 10(1), 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. McGraw-Hill.

- Simon, F. B. (2006). Introduction to Systemic Therapy and Counselling (3rd ed.). Carl-Auer Verlag.

- Sterling, P., & Eyer, J. (1988). Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In S. Fisher & J. Reason (Eds.), Handbook of life stress, cognition and health (pp. 629–649). Wiley.

- ten Have, H., de Beaufort, I., Mackenbach, J., & van der Heide, A. (2013). Ethics and public health: Current issues and challenges. Bioethics, 27(1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Tronto, J. C. Tronto, J. C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge.

- van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

- World Health Organization. (1948). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).