1. Introduction

In recent years, the discourse surrounding curriculum reform has shifted toward more inclusive and culturally responsive paradigms (Luckett & Shay, 2020). This global trend underscores the importance of contextualizing educational content by incorporating local knowledge systems, indigenous epistemologies, and sociocultural realities into formal curricula, particularly in developing nations of the Global South (Ajani, 2025). The homogenizing tendencies of standardized education, often inherited from colonial structures, have led to a growing recognition of the limitations inherent in universalist models that overlook the value of local perspectives, community practices, and cultural heritage (Amin, 2024). Consequently, integrating local knowledge into curriculum design has emerged as a strategic imperative in creating more equitable, relevant, and transformative educational systems.

In Indonesia, this imperative is reflected in the government's national policy reform, known as Merdeka Belajar (Freedom to Learn), which was launched by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology in 2019. The policy envisions a decentralization of curricular authority, enabling schools and higher education institutions to tailor learning content to regional, cultural, and institutional contexts (Tobondo, 2024). One of its key aspirations is to foster student agency, interdisciplinary learning, and the revitalization of local content within academic structures (Tangwe & Benyin, 2025). Rather than treating local knowledge as ancillary or extracurricular, Merdeka Belajar encourages its integration as a core dimension of pedagogy and curriculum innovation, thereby challenging the dominance of nationally standardized and globally homogenized educational frameworks.

Aceh, located on the northwestern tip of Sumatra, provides a unique sociocultural and political landscape for examining such curricular transformations. As a region with special autonomy status following the 2005 Helsinki Peace Agreement, Aceh maintains a distinct identity shaped by Islamic jurisprudence (qanun), a history of protracted conflict, and strong communal traditions rooted in customary law (adat). These characteristics position Aceh not only as a symbol of local resilience and cultural pride but also as a strategic site for implementing context-sensitive curriculum reforms that reflect local wisdom, belief systems, and community values (Abubakar et al., 2022). While primary and secondary education in Aceh has seen efforts to integrate local content, such as folklore, traditional law, and historical narratives, there remains a paucity of empirical studies examining how local knowledge is operationalized within the context of higher education curriculum reform.

This study addresses that gap by focusing on curriculum innovation within universities and higher education institutions in Aceh. Despite national encouragement through the Merdeka Belajar policy, higher education institutions face multifaceted challenges in embedding local knowledge into teaching and learning processes. These include institutional inertia, accreditation rigidities, a lack of pedagogical training in culturally responsive approaches, and tensions between universal academic standards and regional particularities (Joshi, 2024). Given the tension between policy aspirations and institutional realities, it is crucial to examine how educators and curriculum developers in Aceh interpret, adapt, and apply local knowledge in their academic practices. Accordingly, this study is guided by the following research questions:

How do lecturers and curriculum developers perceive the role of local knowledge in higher education?

What strategies are employed to integrate local content into curriculum design and delivery?

What institutional, cultural, and systemic factors influence the success or limitation of such integration?

By engaging with these questions through a qualitative lens, this research aims to contribute to the broader theoretical and practical understanding of curriculum contextualization in higher education. It also seeks to offer insights for policy, curriculum development, and pedagogical design in regions seeking to reconcile global academic frameworks with local cultural integrity.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions and Frameworks of Local Knowledge in Education

Local knowledge, also referred to as Indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge, or community wisdom, has been conceptualized as the accumulated cultural, ecological, spiritual, and practical understandings specific to a particular geographic and sociocultural context (Brondízio et al., 2021). In education, local knowledge is not merely content to be taught; it constitutes a framework of knowing and being that challenges dominant epistemologies, especially those derived from Eurocentric models (Zidny et al., 2020). The incorporation of local knowledge into curricula is viewed as a means to promote cultural identity, linguistic preservation, and context-based problem-solving skills among learners (Assefa & Mohammed, 2022).

Pedagogically, integrating local knowledge aligns with constructivist learning theory, which posits that students build meaning through their interactions with the world around them (Al Abri et al., 2024). Scholars have argued that when learners encounter content that reflects their lived experiences, learning becomes more meaningful, transformative, and empowering (Al-Husban & Al’Abri, 2024). This integration also contributes to the development of what UNESCO terms "culturally sustaining education," wherein schools serve as platforms for the continued vitality of local traditions and values (Mould, 2022).

2.2. Global and Regional Models of Curriculum Contextualization

Efforts to contextualize curriculum have been undertaken across multiple regions, particularly in postcolonial and multilingual societies. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, countries such as Kenya and Ghana have sought to incorporate indigenous ecological knowledge into science and environmental education (Chimbutane, 2023). Similarly, in the Pacific Islands, curriculum reform has emphasized storytelling, communal practices, and traditional ecological management as valid sources of knowledge (Nunn et al., 2024).

In Southeast Asia, regional discourse around curriculum contextualization is gaining traction. Malaysia has developed "cultural modules" integrated into school curricula that reflect ethnic diversity and traditional values. The Philippines has also undertaken efforts to incorporate ethnolinguistic knowledge through its Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) program, reinforcing community identity while enhancing academic outcomes (Escarda et al., 2024). These models underscore a global consensus that curricular relevance is key to educational quality and equity, particularly in multicultural societies.

2.3. Studies on Merdeka Belajar and Cultural Responsiveness

Indonesia's Merdeka Belajar policy represents a shift toward educational democratization, granting autonomy to teachers and institutions to design context-specific curricula tailored to their needs. The framework emphasizes student-centered learning, interdisciplinary approaches, and the integration of local content as part of national learning outcomes (Putri, 2021). Within this policy, the concept of Profil Pelajar Pancasila advocates for six core student attributes, including cultural identity, creativity, and critical thinking elements, which are closely aligned with the goals of culturally responsive education (Suratmi & Hartono).

Several studies have examined the impact of Merdeka Belajar in primary and secondary education. For example, the research found that the policy encourages innovative pedagogies, yet its implementation often lacks alignment with teacher competencies and institutional readiness (Kuznetsova et al., 2024). The other researchers noted that, while there is a rhetorical emphasis on local content, many higher education institutions still rely on nationally standardized materials that marginalize regional diversity (Pineda & Mishra, 2023). These findings suggest that without systemic support and conceptual clarity, the policy's cultural responsiveness goals may remain aspirational rather than transformative.

2.4. Challenges in Curriculum Reform in Developing Nations

Curriculum reform efforts in developing nations frequently encounter a complex array of challenges. Institutional inertia, rigid accreditation frameworks, and limited professional development opportunities are among the most persistent barriers (Al-Worafi, 2024). Additionally, tension exists between national education policies, which often prioritize international competitiveness, and local demands for relevance and equity (Puad & Ashton, 2023). This dichotomy leads to what scholars term the "curriculum dilemma," where educators must navigate between global benchmarks and the cultural realities of their students (Fitzgerald et al., 2023).

In contexts like Indonesia, particularly in peripheral regions such as Aceh, logistical issues such as infrastructure, political decentralization, and socio-religious considerations further complicate curriculum innovation. The integration of local knowledge is often hampered by insufficient research on indigenous pedagogies, lack of institutional commitment, and the undervaluing of non-Western knowledge systems in academic settings (Silvestru, 2023). These structural and epistemic challenges necessitate a rethinking of how curriculum development is approached, especially in higher education settings tasked with cultivating both academic excellence and cultural integrity.

3. Theoritical Framework

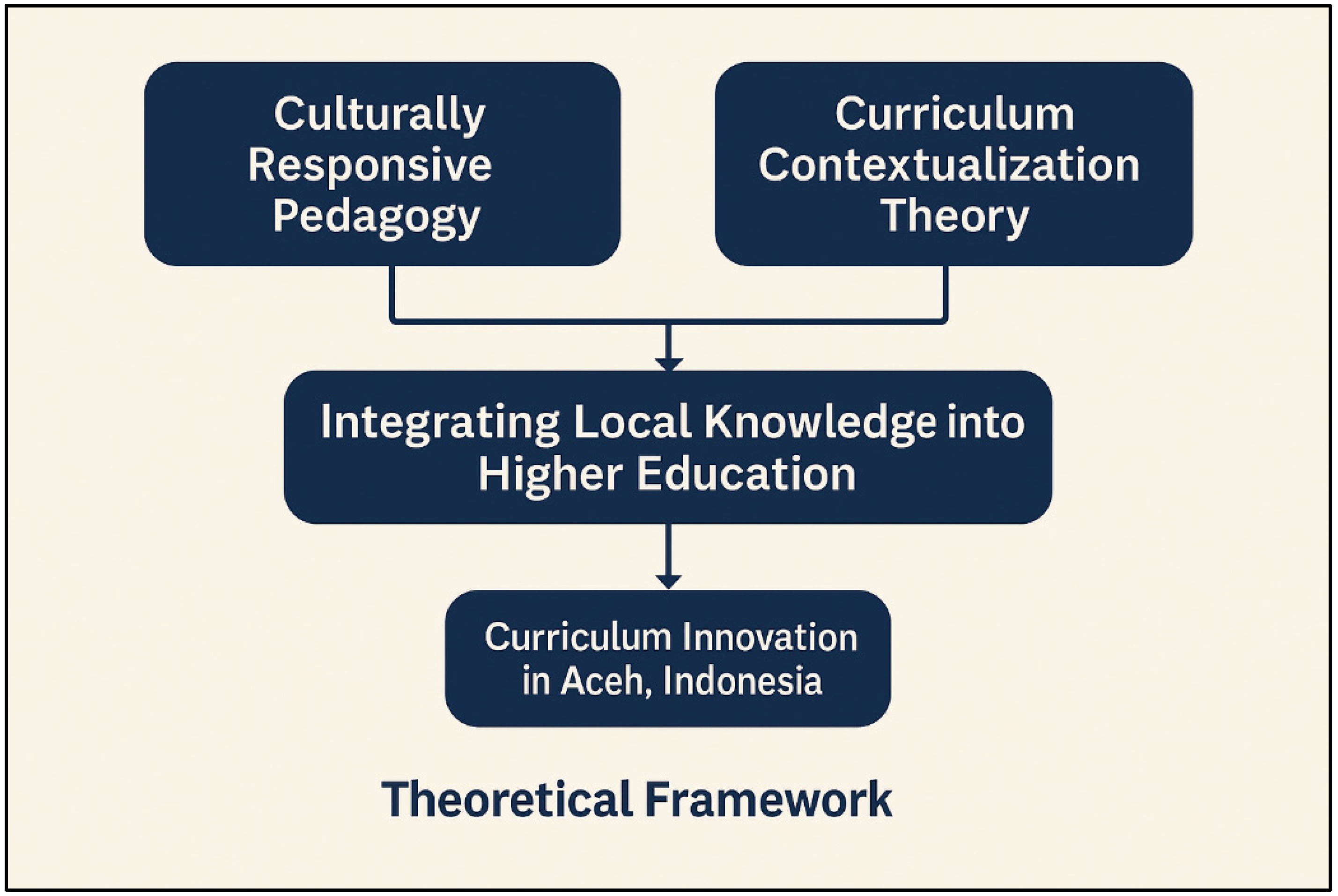

This study is grounded in two complementary theoretical frameworks: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) and Curriculum Contextualization Theory. Together, these frameworks provide a conceptual foundation for understanding how local knowledge can be meaningfully integrated into higher education curricula, particularly within the unique sociocultural and political context of Aceh.

3.1. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP)

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP), as articulated by Geneva Gay (2018), emphasizes the need for educators to incorporate students' cultural backgrounds, languages, and lived experiences into teaching and learning processes (Chang & Viesca, 2022). CRP posits that education should not be culturally neutral; instead, it must actively engage with and validate the cultural assets of learners to enhance academic success and identity development(Wahed & Pitterson, 2023). Within this framework, the inclusion of local knowledge is not merely additive but transformative. It reshapes the curriculum, pedagogy, and teacher-student relationships to reflect the sociocultural realities of the community.

CRP aligns with the goals of the Merdeka Belajar policy, which encourages localized curriculum design and student-centered learning approaches. In higher education, this requires lecturers and curriculum developers to engage in critical reflection about whose knowledge is privileged, how cultural knowledge is positioned in the curriculum, and what pedagogical strategies are appropriate in specific contexts (Rumondor, 2024).

3.2. Curriculum Contextualization Theory

Curriculum Contextualization Theory draws on the curriculum studies literature, which challenges universalist models of education. This theory asserts that curriculum content, structure, and delivery must be adapted to reflect the unique cultural, historical, and geographic context in which it operates (Ngoasong, 2022). Contextualization involves aligning educational experiences with the local sociocultural context to enhance learner relevance, motivation, and critical engagement.

In the case of Aceh, curriculum contextualization implies embedding regional values, Islamic perspectives, local wisdom (kearifan lokal), and traditional ecological knowledge into the learning process. The theory encourages participatory curriculum development that involves local stakeholders, including educators, cultural leaders, and community members, to co-construct knowledge that is both academically rigorous and culturally grounded (Fernández-Villarán et al., 2024). This theoretical orientation is particularly relevant in post-conflict regions, where rebuilding educational identity is closely tied to cultural restoration and social reconciliation. It also serves as a response to critiques of the dominance of globalized Western knowledge systems in higher education, offering a pathway for decolonizing the curriculum and restoring epistemic sovereignty in marginalized regions.

3.3. Intersection of CRP and Contextualization in the Study

By combining Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Curriculum Contextualization Theory, this study situates the integration of local knowledge as both a pedagogical necessity and a curricular imperative (Nataño, 2023). This dual perspective enables the research to examine not only how local knowledge is incorporated (content-wise) but also how it is implemented (pedagogically and institutionally) within the framework of Merdeka Belajar. These theories inform the design of the research instruments, guide the interpretation of data, and provide the basis for deriving practical recommendations for inclusive, context-sensitive curriculum reform in Aceh and similar cultural settings.

Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework underpinning this study. The integration of local knowledge into higher education is informed by two foundational theories: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) and Curriculum Contextualization Theory

. CRP emphasizes the need for a pedagogy that acknowledges and validates students' diverse cultural backgrounds, thereby fostering their identity, motivation, and engagement in the learning process (Gay, 2010). This approach ensures that local values and indigenous epistemologies are not peripheral but central to educational design. Meanwhile, Curriculum Contextualization Theory supports the adaptation of curriculum content, structure, and delivery to align with the sociocultural, historical, and regional realities of learners (Schwab, 2013; Thaman, 2003). When applied together, these theories provide a synergistic foundation for embedding local knowledge as both content and process in higher education reform. The integration of these two perspectives enables a transformative approach to curriculum development, particularly in Aceh, a region with distinct religious, historical, and cultural characteristics. Ultimately, this theoretical synthesis leads to curriculum innovation as institutions respond to the

Merdeka Belajar policy by developing localized and culturally relevant academic programs..

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

A qualitative case study approach was employed to explore the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula within the context of Aceh, Indonesia. This design was chosen due to its ability to provide an in-depth understanding of complex educational phenomena in real-life settings (Amiruddin et al., 2024). Through this approach, the processes by which curriculum innovation was interpreted and implemented under the Merdeka Belajar policy were examined in detail.

4.2. Research Site and Participants

The study was conducted across several higher education institutions in Aceh Province, a region known for its unique sociocultural and political context. A total of 100 participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure representation from key stakeholder groups. These participants included 60 university lecturers from various academic departments, 25 curriculum developers and academic coordinators, and 15 policymakers involved in educational planning and curriculum oversight (Tabel 1). All participants were selected based on their experience, institutional roles, and direct involvement in curriculum design and implementation.

4.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted between January and March 2025. A total of 60 in-depth interviews were conducted, each lasting approximately 45 to 60 minutes. Additionally, eight focus group discussions were conducted, with 5 to 8 participants in each group. The interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in Bahasa Indonesia, audio-recorded with the participant's consent, and later transcribed verbatim. All data collection procedures were conducted following research ethics and confidentiality protocols approved by the institutional ethics committee.

4.4. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase model (Peel, 2020). In the initial phase, transcripts were read repeatedly to gain familiarity with the content. Codes were then generated systematically across the dataset. The resulting codes were organized into potential themes, which were reviewed, refined, and clearly defined. To facilitate coding and theme development, NVivo 12 software was utilized. To ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of findings, triangulation, member checking, and peer debriefing techniques were applied. Final themes were determined through iterative discussions among the research team.

Table 1.

University in Aceh, Indonesia, that organizes the Merdeka Curriculum.

Table 1.

University in Aceh, Indonesia, that organizes the Merdeka Curriculum.

| University Name |

Ownership Status |

Domicile |

Information |

| Universitas Syiah Kuala |

State University |

Banda Aceh City |

One of the largest universities in Aceh that offers a wide range of study programs and is renowned for its commitment to educational innovation |

| Universitas Islam Negeri Ar-Raniry Aceh |

State University |

Banda Aceh City |

The university is known for its programs that combine Islamic education with other disciplines. |

| Universitas Malikussaleh |

State University |

Lhoksumawe City |

Located in Lhokseumawe, the university is known for its engineering and science programs. |

| Universitas Teuku Umar |

State University |

Meulaboh City |

Located in Meulaboh, the university offers a range of educational programs and continually updates its teaching approach. |

| Universitas Samudra |

State University |

Langsa City |

Located in Langsa, the university offers numerous study programs and is recognized for its contributions to education and research in the eastern region of Aceh. |

| Universitas Almuslim |

Private University |

Bireun |

Located in Bireuen, the university is known for its science and technology programs. |

| Politeknik Lhoksumawe |

State University |

Lhokseumawe City |

Although it is a polytechnic, this institution may also be involved in implementing the Merdeka Belajar Curriculum, especially in technical and vocational programs. |

| Universitas Serambi Mekkah |

Private University |

Banda Aceh City |

The university focuses on Islamic education as well as other study programs. |

5. Results

This section presents the study's findings, derived from in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with 100 participants, including lecturers, curriculum developers, and policymakers from various higher education institutions across Aceh, Indonesia. Thematic analysis was used to organize and interpret the qualitative data, revealing key patterns and perspectives related to the integration of local knowledge into curriculum innovation within the framework of the Merdeka Belajar policy. The results are structured around four major themes that emerged during analysis: 1. Perceptions of Local Knowledge in Higher Education, 2. Strategies and Practices for Curriculum Integration, 3. Institutional and Systemic Challenges, and 4. Enabling Factors and Opportunities for Innovation. These themes reflect not only the participants' lived experiences and institutional realities but also illustrate broader sociocultural dynamics influencing educational reform in Aceh. Excerpts from participant narratives are included to support the analysis and enhance the credibility of the findings. A deeper interpretation follows the presentation of results in the discussion section, where connections are drawn between the findings and the theoretical framework, as well as the existing literature.

5.1. Demographic Profile of Participants

Table 2 presents the demographic profile of 100 participants involved in the study, comprising university lecturers (60%), curriculum developers (25%), and education policymakers (15%) across higher education institutions in Aceh. A majority (75%) were affiliated with state universities, while the remaining 25% came from private institutions. Geographically, 65% were based in urban areas and 35% in rural or regional locations, allowing for contextual representation. Among the lecturers, 40% had over 10 years of teaching experience, 40% had 6–10 years, and 20% had 1–5 years. Participants also came from diverse academic backgrounds, including Education and Social Sciences (38%), Islamic Studies (22%), Engineering and Technology (20%), and Science and Health (20%). This demographic diversity enriched the study's exploration of how local knowledge is integrated into higher education curricula under the

Merdeka Belajar policy.

5.2. Validity and Reliability of Research Data

Table 3 summarizes the strategies used to ensure the validity and reliability of the qualitative data in this study. To establish credibility, triangulation across participant groups, member checking, and prolonged engagement were applied to verify the accuracy and depth of findings. Transferability was addressed through rich contextual descriptions, enabling readers to assess the applicability of results to similar settings. Dependability was maintained by documenting a transparent audit trail and conducting peer debriefings to ensure consistency in coding and interpretation. Finally, confirmability was reinforced through reflexive journaling and the use of NVivo 12 software, which supported systematic data management and analytical traceability. These strategies collectively ensured the trustworthiness of the study, adhering to the qualitative rigor framework outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

5.3. Themes Finding of Research

5.3.1. Perceptions of Local Knowledge in the Curriculum

The perception of local knowledge (kearifan lokal) among participants was predominantly positive, with respondents recognizing its critical role in shaping a culturally responsive and contextually grounded higher education curriculum. Rather than viewing it as supplemental material, participants positioned local knowledge as a philosophical and pedagogical foundation—one that connects academic instruction with students' heritage, local environments, and societal values. The integration of local wisdom was widely viewed as a means to support character development, enhance cultural relevance, and align with the national vision of the Profil Pelajar Pancasila, as emphasized in Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar policy. Several lecturers and curriculum developers described the process as an effort to "membumikan ilmu"—literally “grounding knowledge”—to make academic learning more meaningful and reflective of students' lived experiences.

However, respondents also identified persistent barriers. A recurring concern was the academic marginalization of local knowledge, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) faculties, where such content is often viewed as lacking in scientific rigor or institutional relevance. This tension between the universalism of formal academic standards and the contextualism of local knowledge was frequently cited as a core challenge in achieving broader curricular acceptance.

Despite these obstacles, examples of innovation and promising practices emerged. Some institutions had institutionalized local knowledge through elective courses, while others had founded research centers dedicated to local culture and indigenous studies. Collaborative curriculum development involving community leaders, religious scholars, and cultural practitioners was also reported as an effective strategy for enhancing legitimacy and implementation. Particularly noteworthy were multidisciplinary models that integrated local wisdom with scientific knowledge, such as in agroecology and disaster risk education, which were seen to enhance relevance and engagement. “In our education faculty, we developed a learning model where students co-teach in pesantren using local proverbs to explain abstract concepts. It bridges language and logic beautifully.” (Lecturer, Universitas Syiah Kuala). In this theme, we summarize that While systemic challenges remain, especially in academic recognition and institutional frameworks, the drive to legitimize and innovate through local content was gaining momentum across higher education institutions in Aceh.

Table 4.

Participants’ Perceptions of Local Knowledge in the Curriculum.

Table 4.

Participants’ Perceptions of Local Knowledge in the Curriculum.

| Subtheme |

Quote |

Participant Role / Institution |

| Cultural identity and civic values |

“Local knowledge teaches students to understand who they are and where they belong in society.” |

Lecturer, Universitas Samudra |

| Pedagogical philosophy (membumikan ilmu) |

“It helps to bring abstract concepts down to the reality of our students’ communities.” |

Curriculum Developer, Universitas Teuku Umar |

| Alignment with Profil Pelajar Pancasila

|

“It supports the spirit of independent and context-based learning encouraged by Merdeka Belajar.” |

Academic Coordinator, Universitas Syiah Kuala |

| Academic marginalization in STEM |

“Local content is still seen as soft knowledge—our engineering faculty rarely touches it.” |

Lecturer, Universitas Malikussaleh |

| Curriculum innovation through pesantren |

“We co-teach with pesantren using local proverbs to explain abstract concepts. It bridges logic and culture.” |

Lecturer, Universitas Syiah Kuala |

| Multidisciplinary integration |

“We merged agroecological practices with indigenous knowledge to create sustainable farming modules.” |

Researcher, Universitas Almuslim |

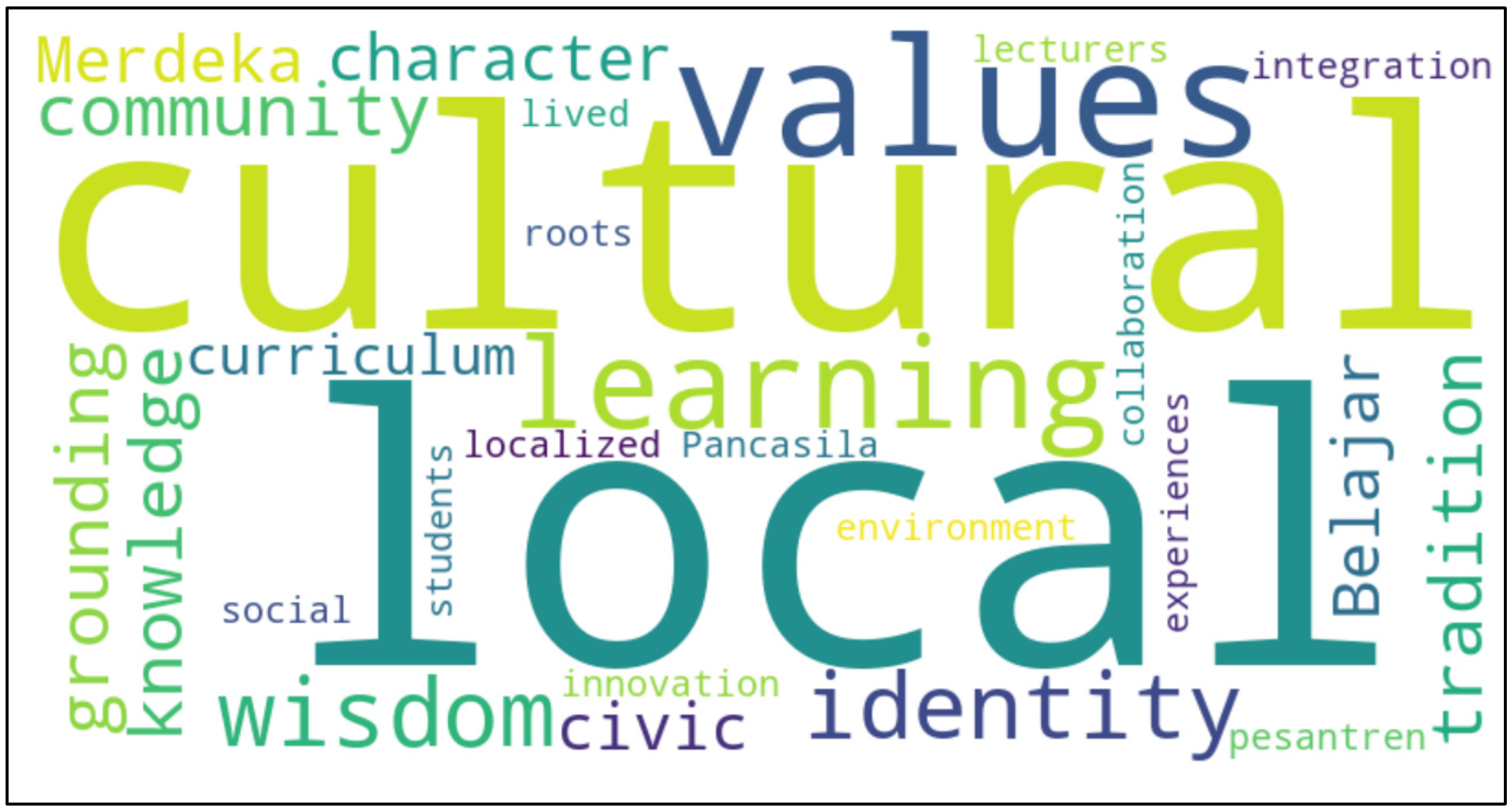

Figure 2 presents a word cloud depicting prominent thematic keywords derived from the qualitative data. The visualization illustrates the lexical emphasis placed by participants on core concepts, including “local wisdom,” “cultural identity,” “tradition,” “community,” and “curriculum integration.” These terms reflect recurring values and themes associated with efforts to contextualize education by incorporating local knowledge. Notably, terms like “grounding knowledge,” “civic values,” and “lived experiences” indicate the pedagogical and philosophical orientations embedded in the discourse. The presence of policy-linked keywords, such as Merdeka Belajar and Pancasila, reinforces the participants’ alignment with national educational reforms. At the same time, terms like

innovation,

collaboration, and

pesantren emphasize the varied strategies and cultural foundations shaping curriculum design. This word cloud serves as a visual summary of how local knowledge is conceptualized and articulated across roles, providing insight into the epistemological and practical dimensions of curriculum transformation in post-pandemic Indonesian higher education.

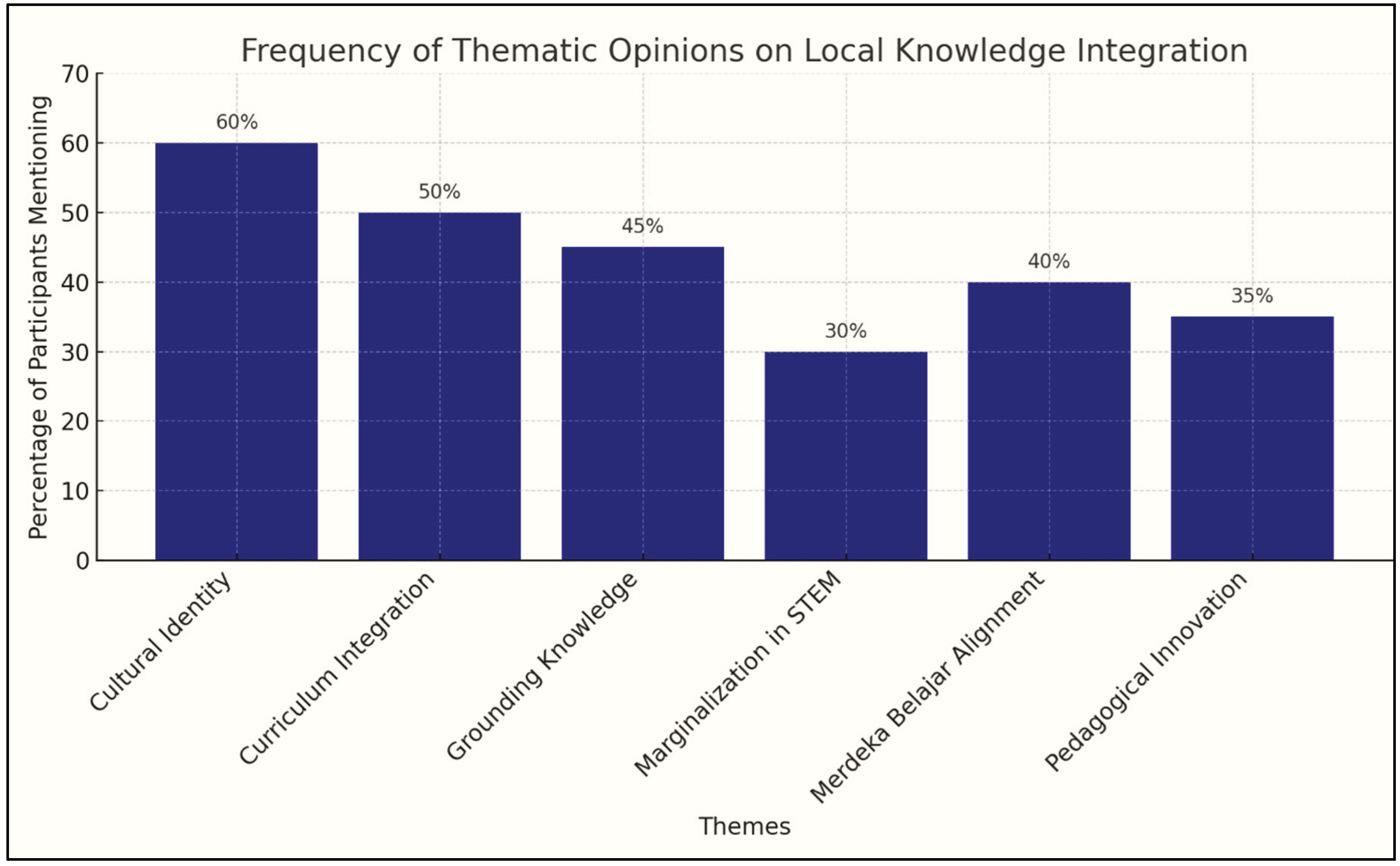

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of thematic opinions expressed by participants concerning the incorporation of local knowledge into higher education curricula. The most frequently mentioned theme was cultural identity (60%), underscoring the perception that integrating local knowledge serves as a key mechanism for strengthening students’ awareness of their heritage and societal roles. This aligns closely with the national agenda of

Profil Pelajar Pancasila. Curriculum integration (50%) and grounding knowledge in local realities (45%) were also widely cited, reflecting pedagogical concerns regarding how to embed local content in meaningful and context-sensitive ways. Meanwhile, alignment with Merdeka Belajar (40%) indicated institutional efforts to contextualize national policies with regional cultural practices. Conversely, marginalization in STEM disciplines (30%) emerged as a notable barrier, highlighting ongoing skepticism about the academic legitimacy of local knowledge, especially in technical fields. Pedagogical innovation (35%) was viewed as a strategic opportunity to bridge global competencies with local insights, particularly through interdisciplinary teaching and community-based projects. The distribution of responses reveals both strong support for the relevance of local knowledge and recognition of structural and epistemological challenges in realizing its full curricular potential.

5.3.2. Methods of Integration: Themes, Community-Based Learning, Assessment

Participants described a variety of pedagogical and institutional strategies for embedding local knowledge into higher education curricula. A widely recognized approach was the thematic embedding of culturally rooted content—such as Acehnese history, adat (customary law), traditional ecological knowledge, and oral literature—into course syllabi. This strategy was particularly prevalent in faculties of the humanities, education, and social sciences, where lecturers adapted teaching materials and classroom discussions to reflect local realities and cultural heritage better. Another prominent method was the implementation of community-based learning, notably through programs like Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN) and other forms of service learning. These initiatives enabled students to engage directly with local communities, co-producing knowledge through collaborative research, documentation, and social projects. Such field-based learning experiences were seen as vital in bridging theoretical instruction with the lived experiences and wisdom of Indigenous communities. As one curriculum developer from Universitas Teuku Umar noted: “Our curriculum includes modules where students work with coastal communities to document traditional fishing techniques, which they later analyze through sustainability frameworks.”

Assessment methods were also adapted to capture student engagement with local knowledge. Project-based evaluations, reflective journals, and participatory community mapping were commonly employed. These approaches encouraged students to critically analyze their field experiences, propose innovative solutions grounded in local contexts, and reflect on the cultural and environmental dimensions of their learning. In particular, participatory mapping stood out as both pedagogically enriching and socially empowering. Students worked alongside community members to document local spatial knowledge—such as traditional fishing zones, sacred spaces, and historical landscapes—thereby validating Indigenous perspectives while contributing to community development goals. Collectively, these methods reflect a pedagogical shift toward experiential, reflective, and collaborative learning, which aligns with the core principles of Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar policy. They also signify an institutional commitment to culturally responsive education that is grounded in local wisdom, socially relevant, and capable of fostering interdisciplinary thinking.

Table 5 summarizes the primary strategies employed by higher education institutions in Aceh to integrate local knowledge into the curriculum. The most common approach involved thematic embedding, whereby course content was aligned with local contexts such as Acehnese culture,

adat traditions, and ecological practices. This approach enabled instructors to contextualize academic knowledge and enhance student engagement by incorporating relevant sociocultural narratives. Community-based learning was also a prominent model, particularly through

Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN) or similar service-learning programs. These initiatives enabled students to collaborate directly with residents, facilitating two-way knowledge exchange and fostering social responsibility. In terms of assessment, project-based evaluations

, and reflective journaling were favored for their ability to capture both analytical and experiential dimensions of student learning. These tools not only assessed academic performance but also documented the development of civic values and critical awareness. Ultimately, participatory community mapping emerged as an inclusive and transformative practice that validated Indigenous spatial knowledge while enhancing student understanding of local development dynamics. Collectively, these methods demonstrate a holistic, student-centered, and culturally responsive approach to curriculum innovation, aligning with the

Merdeka Belajar framework.

5.3.3. Institutional and Policy-Related Challenges

Key challenges included the absence of institutional guidelines, limited lecturer capacity, and pressure to align with national accreditation standards that emphasize universal and standardized competencies. Respondents reported a lack of administrative support, insufficient training in culturally responsive pedagogy, and tensions between the need for curriculum flexibility and bureaucratic accountability. “We are encouraged to localize our content, but the accreditation system still uses national rubrics with no indicators for local integration.” (Academic Coordinator, Universitas Malikussaleh).

Table 4 synthesizes the key institutional and policy-related challenges that hinder the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh. A consistent concern among participants was the lack of institutional guidelines. Although the national

Merdeka Belajar policy encourages contextualization, many universities have not developed internal regulations or curriculum blueprints to operationalize the integration of local content. As a result, educators were left without clear directives or quality benchmarks, leading to fragmented or informal practices.

Another significant barrier was the limited capacity of lecturers. Respondents expressed that most teaching staff had not received adequate training in culturally responsive pedagogy or interdisciplinary curriculum design. This lack of capacity made it difficult for lecturers to confidently embed local knowledge into their syllabi or employ relevant assessment methods. Moreover, the misalignment between localized content and national accreditation standards was a recurring theme. Many participants feared that innovative, locally grounded modules might not fulfill standardized criteria set by national assessment bodies, thus threatening institutional performance indicators. Administrative support was also reported as insufficient. Several lecturers highlighted a lack of budgetary allocation, the absence of leadership support, and a general lack of institutional prioritization for integrating local knowledge. These limitations created practical barriers to implementation, even when faculty enthusiasm was high.

Finally, participants pointed to bureaucratic rigidity as a structural obstacle. Curriculum design and academic credit allocation remain highly centralized and inflexible, leaving little room for innovation. The pressure to adhere to strict program structures often discourages experimentation and adaptation, which are necessary for embedding local content in a meaningful way. Together, these challenges underscore the gap between national educational aspirations and institutional realities. Without systemic changes at both policy and administrative levels, efforts to incorporate local knowledge risk being inconsistent, symbolic, or unsustainable. Addressing these barriers is crucial for establishing a truly contextualized and culturally responsive higher education system in Indonesia.

5.3.4. Enabling Factors and Opportunities for Innovation

Several key enabling factors have supported the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh. Institutional leadership, particularly from rectors and deans, played a critical role in legitimizing curriculum reform, as reflected in the statement, “The Rector supported our local module and gave it a dedicated course slot.” Community-academic partnerships also contributed significantly, with syllabi often co-developed alongside village elders and NGOs, fostering culturally grounded content. Faculty-level autonomy enabled flexible curriculum adaptation without compromising national learning standards. As one lecturer stated, “We could adapt our modules as long as learning outcomes were met.” Moreover, research-based development—utilizing student theses and local fieldwork enabled local knowledge to be recognized as academically rigorous, while cross-disciplinary collaboration created space for innovative teaching practices, such as modules jointly designed by engineering and anthropology students. Collectively, these factors highlight a dynamic process of curriculum innovation that bridges academic standards with local cultural relevance.

The integration of local knowledge into higher education in Aceh has been enabled by a set of institutional and pedagogical factors that collectively foster innovation. As presented in

Table 7, institutional leadership played a pivotal role. Support from rectors, deans, or program heads created strategic momentum, whether through policy endorsements, course allocations, or resource provision. Participants consistently emphasized the importance of top-down encouragement in legitimizing efforts to localize curricula. Equally important were community-academic partnerships, particularly those that included village elders, traditional leaders, religious figures, or local NGOs. These collaborations not only enriched course content but also fostered mutual trust and relevance. In some cases, entire syllabi were co-developed with community input, ensuring that academic content remained grounded in a social context.

A critical enabling condition was curriculum autonomy at the faculty level. Faculties with flexibility in course design were able to innovate while still aligning with accreditation standards. Respondents noted that as long as learning outcomes were maintained, locally grounded materials could be introduced without bureaucratic constraints.

Several lecturers described how research-based content development, especially from student theses or faculty fieldwork, contributed to the formal curriculum. This not only created a feedback loop between research and teaching but also validated local knowledge as academically rigorous. Additionally, cross-disciplinary collaboration enabled different faculties to integrate local perspectives into diverse fields, such as disaster education, sustainable agriculture, and public health. Collectively, these enabling factors demonstrate that local knowledge integration is not only a cultural imperative but also an institutional innovation process, one that thrives on leadership, flexibility, collaboration, and grounded research.

The integration of local knowledge into higher education in Aceh is the result of collaborative efforts involving multiple stakeholders, each playing distinct but complementary roles in curriculum innovation. As illustrated in

Table 8, lecturers are at the forefront of curricular adaptation, embedding themes such as

adat (customary law), traditional ecological knowledge, and oral literature into course syllabi. They also implement innovative pedagogical approaches, such as reflective journals, problem-based learning, and contextual storytelling, while supervising students in community-based projects. Institutional leaders—such as rectors and deans—provide strategic support by approving localized courses, allocating resources, and promoting programs like

Kuliah Kerja Nyata (Community Service Learning) and applied research initiatives. Curriculum developers act as mediators between national policy and institutional practice, ensuring that learning outcomes incorporate cultural relevance through community consultations. Community leaders, including traditional and religious figures, contribute cultural legitimacy by participating in syllabus design, delivering guest lectures, and facilitating participatory learning activities. Students, meanwhile, serve as cultural intermediaries, conducting locally grounded projects and producing academic work that validates Indigenous perspectives. This narrative highlights that local knowledge integration is not an isolated academic endeavor but a systemic reform process driven by a shared commitment and cross-sector collaboration.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh, Indonesia, within the framework of the Merdeka Belajar policy. The findings revealed that local knowledge is widely regarded by educators, policymakers, and curriculum developers as a crucial foundation for contextual and culturally relevant education. Integration occurs through thematic content, community-based learning, and reflective assessment practices. However, structural challenges persist, including limited institutional guidelines, lack of lecturer capacity, and accreditation systems that prioritize standardized indicators over local relevance.

The study contributes to the ongoing discourse on curriculum reform by offering empirical insights into how educational innovation can emerge from the intersection of cultural identity, institutional autonomy, and national policy. It emphasizes that local knowledge is not merely supplementary but central to fostering inclusive, grounded, and socially responsive higher education. The research also underscores the importance of collaborative actor networks—across universities, communities, and policy institutions—in sustaining culturally meaningful curricular transformations.

Despite its contributions, the study is limited by its geographic scope, focusing only on institutions in Aceh. Future research should examine similar efforts across other Indonesian provinces or compare cross-national models to enrich the understanding of culturally responsive curriculum frameworks. Longitudinal studies may also be beneficial in assessing the long-term impact of localized curricula on student outcomes, civic engagement, and academic relevance in diverse educational contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abubakar, A., Aswita, D., Israwati, I., Ferdianto, J., Jailani, J., Anwar, A., Ridhwan, M., Saputra, D. H., & Hayati, H. (2022). The Implementation of Local Values in Aceh Education Curriculum. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 10(1), 165-182. [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O. A. (2025). Rethinking teacher development: blending socially responsible teaching approaches with Indigenous Knowledge to enhance equity and inclusivity. SN Social Sciences, 5(4), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Al-Husban, N., & Al’Abri, K. M. (2024). Cultivating global citizenship education in higher education: Learning from EFL university students’ voices. Citizenship Teaching & Learning, 19(1), 3-19. [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y. M. (2024). Curriculum Reform in Developing Countries: Public Health Education. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research (pp. 1-26). Springer.

- Al Abri, M. H., Al Aamri, A. Y., & Elhaj, A. M. A. (2024). Enhancing student learning experiences through integrated constructivist pedagogical models. European Journal of Contemporary Education and E-Learning, 2(1), 130-149. [CrossRef]

- Amin, T. (2024). Globalization and cultural homogenization: A critical examination. Kashf Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 1(03), 10-20.

- Amiruddin, A., Nurdin, A., Yunus, M., & Gani, B. A. (2024). Social Mainstreaming in the Higher Education Independent Curriculum Development in Aceh, Indonesia: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 12(1), 121-143.

- Assefa, Y., & Mohammed, S. J. (2022). Indigenous-Based Adult Education Learning Material Development: Integration, Practical Challenges, and Contextual Considerations in Focus. Education Research International, 2022(1), 2294593.

- Brondízio, E. S., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., Bates, P., Carino, J., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Ferrari, M. F., Galvin, K., Reyes-García, V., McElwee, P., & Molnár, Z. (2021). Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: Indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46(1), 481-509. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-C., & Viesca, K. M. (2022). Preparing teachers for culturally responsive/relevant pedagogy (CRP): A critical review of research. Teachers College Record, 124(2), 197-224. [CrossRef]

- Chimbutane, F. (2023). Multilingualism and languages of learning and teaching in post-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa. In The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 207-222). Routledge.

- Escarda, G., Petiluna, S., Perdaus, S., Mendoza, R., & Bula, M. (2024). Exploring English Teachers' Experiences on Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE). International Multidisciplinary Journal of Research for Innovation, Sustainability, and Excellence (IMJRISE, 1(3), 1-10.

- Fernández-Villarán, A., Guereño-Omil, B., & Ageitos, N. (2024). Embedding sustainability in tourism education: Bridging curriculum gaps for a sustainable future. Sustainability, 16(21), 9286. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A., Goff, W., & White, S. (2023). The dilemmas inherent in curriculum design: Unpacking the lived experiences of Australian teacher educators. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal)(90), 109-127. [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Teachers College. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=S0YkAQAAMAAJ.

- Joshi, S. C. (2024). Global Curriculum Standards and the Indian Education System: Challenges, Adaptation Strategies, and Policy Implications. Educational Quest, 15(3), 111-131. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, H., Danylchenko, I., Zenchenko, Т., Rostykus, N., & Lushchynska, O. (2024). Incorporating innovative technologies into higher education teaching: Mastery and implementation perspectives for educators. Multidisciplinary Reviews, 7. [CrossRef]

- Luckett, K., & Shay, S. (2020). Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Critical Studies in Education, 61(1), 50-65. [CrossRef]

- Mould, C. D. (2022). Leadership as Design: Using Human-centered Design as a Framework to Understand the Work of Leaders in Innovative Schools. The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Nataño, N. M. (2023). Perspectives on Curriculum Contextualization and Localization as Integral to Promoting Indigenous Knowledge. International Journal of Academic and Practical Research International Journal of Academic and Practical Research, 2(3), 67-76.

- Ngoasong, M. Z. (2022). Curriculum adaptation for blended learning in resource-scarce contexts. Journal of Management Education, 46(4), 622-655. [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P. D., Kumar, R., Barrowman, H. M., Chambers, L., Fifita, L., Gegeo, D., Gomese, C., McGree, S., Rarai, A., & Cheer, K. (2024). Traditional knowledge for climate resilience in the Pacific Islands. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 15(4), e882. [CrossRef]

- Peel, K. L. (2020). A beginner’s guide to applied educational research using thematic analysis. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation, 25(1).

- Pineda, P., & Mishra, S. (2023). The semantics of diversity in higher education: differences between the Global North and Global South. Higher Education, 85(4), 865-886. [CrossRef]

- Puad, L. M. A. Z., & Ashton, K. (2023). A critical analysis of Indonesia's 2013 national curriculum: Tensions between global and local concerns. The Curriculum Journal, 34(3), 521-535. [CrossRef]

- Putri, I. (2021). Engaging Creative Pedagogies to Reframe Environmental Learning in an Indonesian Teacher Education Program Victoria University].

- Rumondor, G. (2024). The Study of The Implementation of Kurikulum Merdeka in Higher Education and Its Effects on Promoting Local Job Opportunities in Northern Sulawesi Oslo Metropolitan University].

- Schwab, J. J. (2013). The practical: a language for curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(5), 591-621. [CrossRef]

- Silvestru, A. (2023). Weaving relations: Exploring the epistemological interaction between indigenous & traditional ecological knowledge and Eurowestern paradigms in education for sustainable development-an umbrella review.

- Suratmi, S., & Hartono, H. Literacy Character Education Planning to Strengthen the Pancasila Student Profile through Local Culture in Early Childhood Education. Golden Age: Jurnal Ilmiah Tumbuh Kembang Anak Usia Dini, 9(1), 145-158. [CrossRef]

- Tangwe, A. T., & Benyin, P. K. (2025). Reimagining Critical Interdisciplinarity. Shifting from the Traditional to the Transformative Paradigm in Higher Education Research and Learning. [CrossRef]

- Thaman, K. H. (2003). Decolonizing Pacific Studies: Indigenous Perspectives, Knowledge, and Wisdom in Higher Education. The Contemporary Pacific, 15(1), 1-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23722020 . [CrossRef]

- Tobondo, Y. A. (2024). Challenges and Solutions in the Implementation of Educational Policies in Indonesia: A Literature Analysis of Merdeka Belajar Kampus Merdeka and Teacher Reform. EDUKASIA: Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran, 5(1), 1157-1164. [CrossRef]

- Wahed, S., & Pitterson, N. (2023). Empowering Diverse Learners: Embracing Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) in Engineering, Higher Education, and K-12 Settings. International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning,.

- Zidny, R., Sjöström, J., & Eilks, I. (2020). A multi-perspective reflection on how indigenous knowledge and related ideas can improve science education for sustainability. Science & Education, 29(1), 145-185. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).