1. Introduction

Obesity remains a global health concern with more than 600 million adults are classified as obese worldwide [

1]. It is estimated that around 20 % of world population will be obese by 2030[

2]. Morbid obesity has become a public health problem resulting in different comorbid conditions and subsequently substantial burden on healthcare system [

3]. It is managed with multimodal approach and in severe cases surgery is effective management option. As obesity rates ascend worldwide, bariatric surgeries have grown into a crucial intervention for individuals suffering from morbid obesity, facilitating significant weight loss. These procedures play a crucial role in managing weight and addressing associated health concerns. However, most of time they result in a great deal of skin as well as soft tissue redundancy following surgery, requiring additional body contouring procedures to fix these physical changes. The growing demand for these procedures highlights the complex impacts of significant weight loss, which include aesthetic, functional, as well as psychosocial components. Abdominoplasty is becoming more popular among individuals who suffered significant weight loss after bariatric surgery, providing a surgical solution to the difficulties that arise post-operation. [

4,

5].

The latest data indicates a rise in the prevalence for overweight, obesity, as well as abdominal obesity of 30.0%, 17.7% and 48.6% respectively when compared to the findings from the 2015 [

6]. The occurrence of overweight to adults aged 18 and older in Malaysia stays below the global rate of 39%. However, there has been a notable increase of the obesity category around 4.7% compared to worldwide incidence [

7].

A variety of therapeutic strategies might be implemented to facilitate weight loss [

8]. The initiatives include the promotion of a healthy lifestyle within various populations, which includes activities like walking and exercise, implementation of intervention programs in places of work, and concentrating on specific demographics including school kids and middle-aged women. Nonetheless, these programs tend to be transient as well as lack sustainability [

9,

10,

11]. There is an increasing trends of bariatric surgery procedures to address patients with a BMI over 35 with obesity-related complications, or patients with a BMI over 40 who have failed non-surgical management. The increasing prevalence of bariatric surgery has established abdominoplasty as a crucial intervention for patients going through excess abdominal tissue following essential weight loss. Abdominoplasty is an operation designed to remove excess skin and fat in abdominal area while also strengthening the abdominal wall muscles. This procedure aims to create an appealing abdomen, utilizing both direct excisional techniques and liposuction techniques [

12]. Additionally, individuals who was given procedures for body contouring adhering to bariatric surgery demonstrated significantly greater long-term weight loss contrasted to a matched group of patients [

13]. Previous studies have identified that alterations in blood components, such as leptin, low-density lipoprotein, as well as triglycerides, are linked to abdominoplasty [

14,

15]

Obesity and significant weight reduction via bariatric surgery may result in various physical, psychological, as well as social issues, such as surplus skin and unsatisfactory body shape. The identified issues have a substantial impact on patients' mobility, self-esteem, sexual activity, low confidence, negatively impacting the quality of life. Abdominoplasty effectively addresses body contour deformities, leading to improvements in physical appearance, positive body image and possibly improving psychological as well as social well-being with improvement in health-related quality of life. Different studies have demonstrated the improvement in overall quality of life after abdominoplasty. A study by Griego MP, et al has shown that 30 patients undergone post-bariatric surgery abdominoplasty experienced improvement in body image perception and quality of life. [

16,

17]. However, the sample size was small in size to generalize the results. Aim of this study is to assess the impact of abdominoplasty on multiple quality-of-life aspects in individuals who have undergone bariatric surgery to clarify how aesthetic surgery modifies self-awareness and self-esteem and influences the QoL. Results of this large cohort of 100 patients can help to generalize the abdominoplasty as a procedure of choice for post bariatric patients

2. Methodology

2.1. Participnats

The cross-sectional survey-based study was conducted with a cohort of 100 patients subsequently selected for abdominoplasty at Villa Dei Fiori Hospital in Acerra from January 2024 to December 2024. Ethical approval from the hospital’s ethical review committee was waived due to retrospective nature and cross sectional survey. Participants ranged in age from 27 to 59 years and maintained a body mass index (BMI) not exceeding 30 kg/m² at the time of selection. To ensure a homogeneous sample and minimize confounding variables, inclusion criteria required that participants were non-smokers and non-diabetic with no history of additional surgical procedures beyond abdominoplasty during the study period. These strict criteria were applied to isolate the effects of abdominoplasty on quality of life without interference from smoking-related healing complications, diabetic comorbidities or other surgical interventions.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection occurred at two distinct time points, preoperatively and one year postoperatively. Each participant completed a quality-of-life questionnaire derived from the official IQMWL test. The questionnaire encompassed seven themes such as general health social and interpersonal relations. Mobility, self-esteem, comfort with food sexual life and work performance. To streamline analysis and enhance clarity for telephone-based responses, we modified the original IQMWL format which typically employs a multi-point scale into a binary response system of “Satisfied” and “Unsatisfied.” This adaptation was made to reduce ambiguity in patient self-reporting, facilitate statistical comparison using McNemar’s test for paired nominal data and accommodate the limitations of verbal communication during interviews ensuring responses were straightforward and reliable. The questionnaires were administered through anonymous telephone interviews conducted by a staff member external to the surgical department. This approach was deliberate aiming to eliminate potential response bias, that could arise from patients’ interactions with their treating surgeons or familiar hospital staff. Preoperative interviews were completed within one month prior to surgery, establishing a baseline while postoperative interviews occurred exactly one year following the procedure to assess long-term outcomes. Responses were recorded verbatim and later categorized into the “Satisfied” or “Unsatisfied” framework for analysis, preserving the anonymity of participants throughout the process.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For analysis we used SPSS 24. Data was assessed using mean along with standard deviation and frequencies along with percentages. For pre procedure and post procedure assessment we used McNemar’s test keeping the P value significant at < 0.05.

3. Results

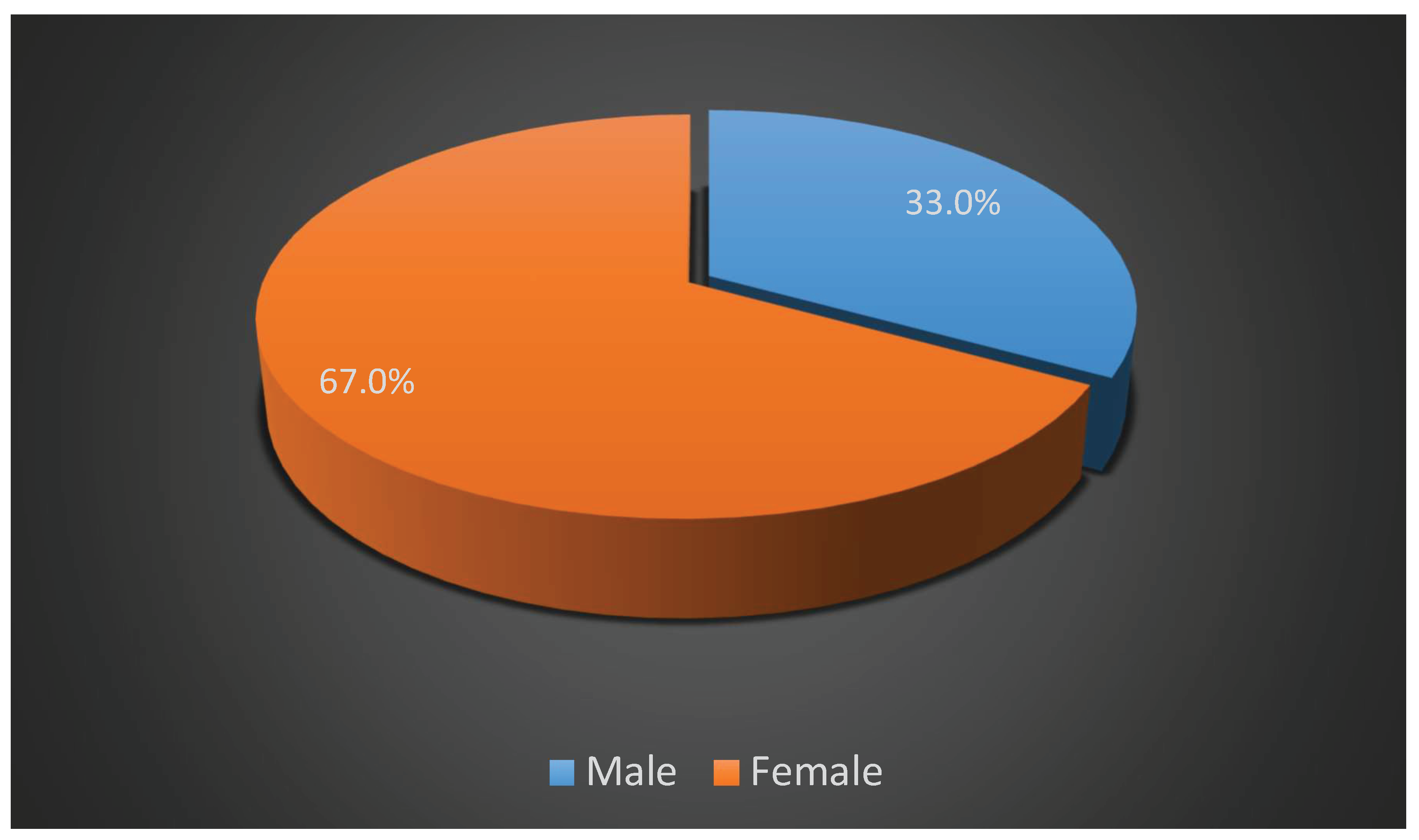

A total of 100 post bariatric patients who underwent abdominoplasty were included in this study. we explored a range of characteristics and quality-of-life outcomes before and after the procedure. The age range of patients was 27 to 58 years with an average age of 42.87 years and a standard deviation of ±9.219 years. Their body mass index (BMI) prior to surgery varied between 25.26 and 29.92 kg/m² averaging 27.8116 kg/m² with a standard deviation of ±1.32352 kg/m². Regarding gender distribution, we found that 33 patients were male (33%) while 67 were female, accounting for 67% reflecting a clear predominance of women in this cohort (

Figure 1). Turning to the quality-of-life assessments we examined seven key dimensions preoperatively using the IQMWL test. For overall health, only 24 patients (24%) expressed satisfaction before surgery leaving 76 (76%) feeling unsatisfied. In terms of social relations 32 patients (32%) reported satisfaction while 68 patients (68%) were dissatisfied. With regard to Mobility, 26 patients (26%) satisfied and 74 (74%) unsatisfied. Self-esteem exhibited the lowest preoperative satisfaction with just 11patients (11%) feeling content and 89patients (89%) expressed dissatisfaction. Dietary comfort showed 30 patients (30%) satisfied while 70 (70%) unsatisfied. Satisfaction rate for Sexual life had 42 patients (42%) as satisfied while 58 (58%) reported dissatisfaction. Finally work performance exhibited 45 patients (45%) satisfied and 55 (55%) unsatisfied (

Table 1).

After abdominoplasty, the postoperative assessments revealed a substantial improvement across all dimensions after one year. For overall health, satisfaction surged to 83 patients (83%) with only 17 (17%) unsatisfied. Social relations represented 90 patients (90%) reporting satisfaction, leaving 10 (10%) unsatisfied. Mobility improved notably as well with 88 patients (88%) satisfied and 12 (12%) still facing some challenges. There was marked improvement in Self-esteem with 84 patients (84%) feeling satisfied while 16 (16%) did not. Dietary comfort showed a more modest gain with 60 patients (60%) satisfied and 40 (40%) unsatisfied. Sexual life exhibited one of the strongest shifts with 92 patients (92%) reporting satisfaction and only 8 (8%) feeling unhappy still. Lastly work performance climbed to 93 patients (93%) satisfied with a mere 7 (7%) unsatisfied (

Table 1).

To evaluate the significance of changes in quality of life we applied McNemar’s test to compare preoperative and postoperative responses across all dimensions.

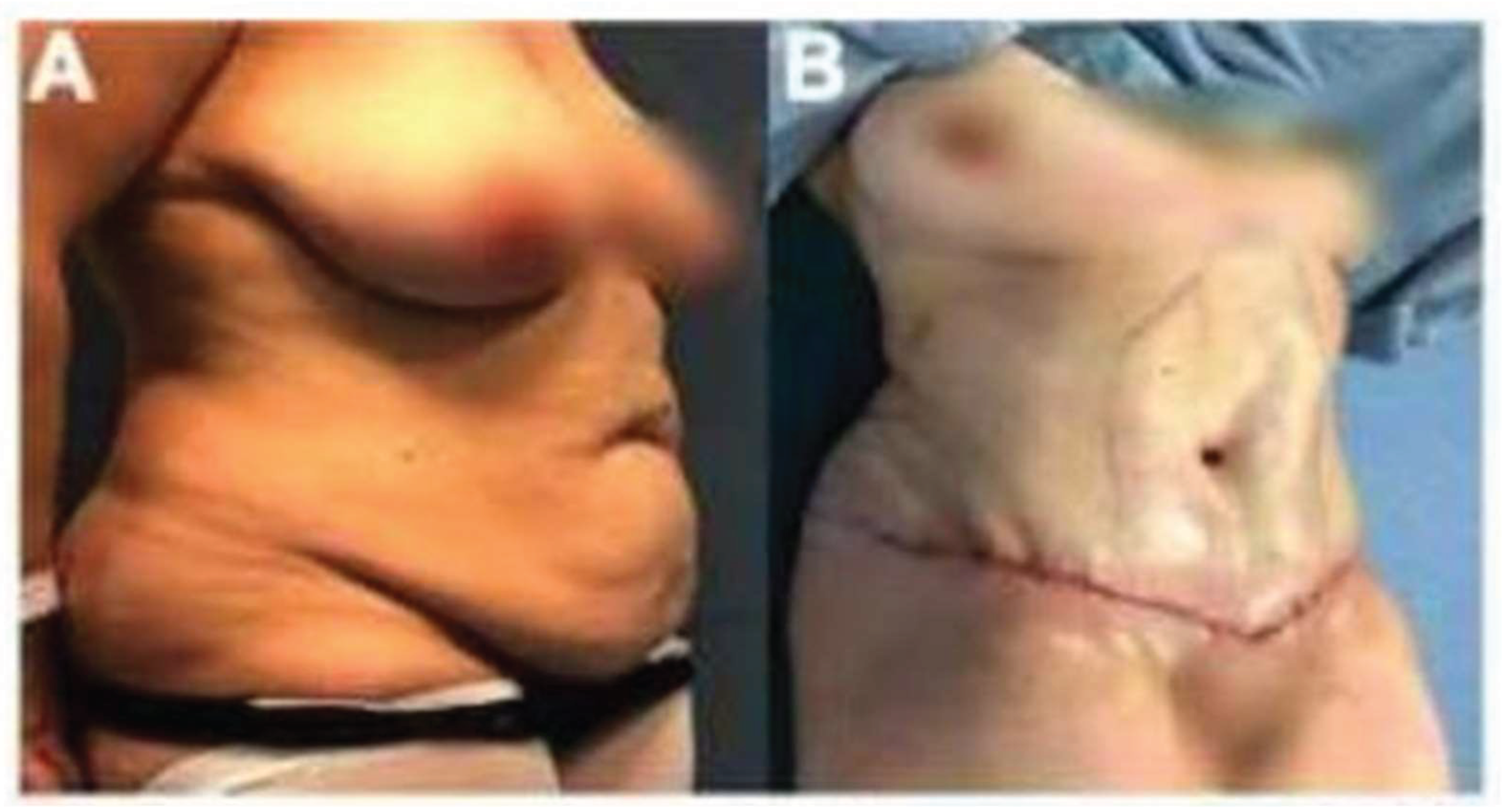

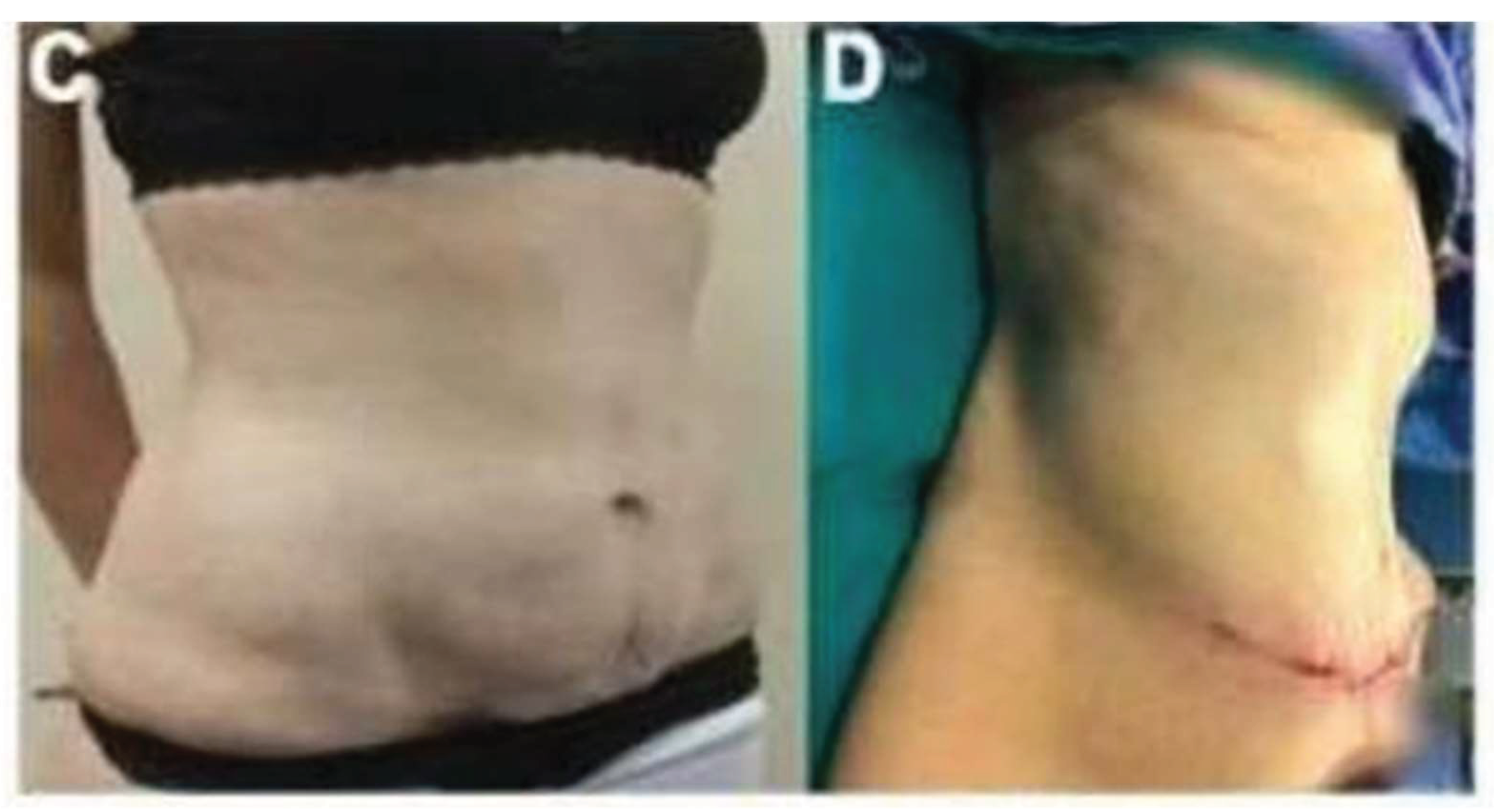

Figure 2 and figure 3, represents the before and after images of two female patients who underwent abdominoplasty. These findings highlight a transformative shift in the patients’ quality of life following abdominoplasty with satisfaction levels rising dramatically across physical, psychological and social spheres underscoring the procedure’s broader impact beyond mere physical contouring.

4. Discussion

Bariatric surgery aims not only to achieve substantial weight loss but also to improve related comorbidities and enhance overall QoL. Historically, surgical success was evaluated using clinical metrics, such as the absence of complications or procedural effectiveness. The assessment of QoL from the patient’s perspective has gained increasing importance across medical disciplines, including plastic surgery. This shift reflects the growing recognition of patient-reported outcomes as key measures of treatment success and overall well-being [

18].

With a cohort ranging in age from 27 to 58 years (mean 42.87 ± 9.219 years) and a preoperative body mass index spanning 25.26 to 29.92 kg/m² (mean 27.8116 ± 1.32352 kg/m²) our findings reveal substantial improvements across seven quality-of-life dimensions one-year post-surgery. The gender distribution with 33 males and 67 females reflects a female predominance consistent with trends in body contouring literature. Employing McNemar’s test to compare preoperative and postoperative responses via the IQMWL test, we documented a shift from pervasive dissatisfaction 24% satisfied with overall health 11% with self-esteem and 42% with sexual life to remarkable gains with postoperative satisfaction reaching 83% 84% and 92% respectively. These results underscore abdominoplasty’s role as a pivotal intervention for enhancing well-being beyond mere physical alteration aligning with and diverging from prior studies in ways that merit detailed discussion.

Comparatively Wan Makhtar et al., investigated weight loss outcomes in 98 patients including 23 post-bariatric individuals, who underwent abdominoplasty [

19]. They noted improved body image as a secondary benefit a finding that resonates with our dramatic self-esteem increase from 11% to 84%. This overlap hints at psychological benefits tied to contouring though their lack of formal quality-of-life metrics limits direct comparison positioning our work as an extension that quantifies these gains.

Papadopulos et al. examined abdominoplasty’s psychological impact in a non-bariatric cohort reporting significant enhancements in self-esteem and mental health six months post-surgery [

20]. Although their aesthetic focus differs from our post-bariatric context the self-esteem parallel is striking with our larger sample and longer one-year follow-up reinforcing the durability of such gains. Our broader assessment encompassing social relations (32% to 90%) and sexual life (42% to 92%) suggests that post-bariatric patients may experience more extensive multidimensional benefits likely due to the removal of excess skin a burden less prevalent in their cohort. This distinction highlights the unique needs of massive weight loss patients where physical and psychosocial restoration intertwine.

Song et al. assessed post-bariatric patients three to six months post-body contouring (including abdominoplasty). They reported notably improvement in the post procedure quality of life assessment of their patients in various domains including self-esteem, sexual satisfaction, physical health and work [

21]. Their findings resonate with our post procedure assessment of QOL.

Our findings highlight a transformative shift in the patients’ quality of life following abdominoplasty with satisfaction levels rising dramatically across physical psychological and social spheres underscoring the procedure’s broader impact beyond mere physical contouring.

Future research could integrate weight outcomes with quality-of-life metrics and complication rates to holistically assess abdominoplasty’s role. Extending follow-up beyond one year could clarify long-term durability while investigating dietary comfort’s lag might refine postoperative care. Our findings position abdominoplasty as a critical adjunct for post-bariatric patients enhancing well-being in ways that transcend physical metrics offering a compelling case for its broader adoption in this population.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion our study of 100 post-bariatric patients shows that abdominoplasty significantly enhances quality of life one-year post-surgery in domains with the highest turnover: social relations (32% to 90%) mobility (26% to 88%) self-esteem (11% to 84%) sexual life (42% to 92%) and work performance (45% to 93%). These findings emphasize its transformative potential though limitations like unreported complications and a one-year follow-up may obscure full long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Feliciano Ciccarelli and Felice Moccia are responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration and writing original draft of the manuscript. Vincenzo Vastarella, Roberto Cuomo and Gorizio Pieretti are responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration and editing the draft of the manuscript. Maria Giovanna Vastarella, Claudia Vastarella and Adelmo Gubitosi participated in resources, supervision, validation and visualization of data.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving the human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was waived due to retrospective nature and cross-sectional survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study will be available on reasonable demand through a valid official email from corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the participants who sincerely helped us with this research. The authors have checked to make sure that our submission conforms as applicable to the Journal’s statistical guidelines described here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed, B.; Konje, J.C. The epidemiology of obesity in reproduction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2023, 89, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vater, A.M.; Fietz, J.; Schultze-Mosgau, L.E.; Lamby, P.E.; Gerauer, K.E.; Schmidt, K.; Jakubietz, R.G.; Jakubietz, M.G. Understanding the Long-Term Effects of Inverted-T-Abdominoplasty on Quality of Life: Insights from Post-Bariatric Surgery Patients. Life 2025, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonio, B.; Ajan, K.; Gayatri, A.; et al. Quality of Life After Bariatric and Body Contouring Surgery in the Australian Public Health System. Journal of Surgical Research 2023, 285, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.R.; da Costa, P.R.; Maia, T.S.; Junior, A.C.; Resende, V. Prospective cohort of parameters of glycemic and lipid metabolism after abdominoplasty in normal weight and formerly obese patiens. JPRAS open 2023, 37, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uimonen, M.; Repo, J.P.; Homsy, P.; Jahkola, T.; Poulsen, L.; Roine, R.P.; Sintonen, H.; Popov, P. Health-related quality of life in patients having undergone abdominoplasty after massive weight loss. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2021, 74, 2296–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IfPH M. National Health & Morbidity Survey. Vol. II: Non-Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors & Other Health Problems. Institute for Public Health Malaysia Kuala Lumpur; 2015.

- Ahmad D. Malaysia and WHO call for more investment in primary health care the 21st century. Y. Yang, Interviewer; 2019.

- El Ansari, W.; Elhag, W. Weight regain and insufficient weight loss after bariatric surgery: definitions, prevalence, mechanisms, predictors, prevention and management strategies, and knowledge gaps—a scoping review. Obes Surg 2021, 31, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios-Diaz, A.J.; Morris, M.P.; Elfanagely, O.; Cunning, J.R.; Davis, H.; Shakir, S.; Broach, R.B.; Fischer, J.P. Impact of panniculectomy and/or abdominoplasty on quality of life: a retrospective cohort analysis of patient-reported outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150, 767e–75e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzita, A.T.; Mab, W.A.; Ismail, M.N. The effectiveness of nutrition education programme for primary school children. Malays J Nutr 2007, 13, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wan Mohamud, W.N.; Musa, K.I.; Md Khir, A.S.; Ismail, A.A.; Ismail, I.S.; Kadir, K.A.; et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult Malaysians: an update. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011, 20, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Berkane, Y.; Saget, F.; Lupon, E.; et al. Abdominoplasty and lower body lift surgery improves the quality of life after massive weight loss: a prospective multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 153, 1101e–10e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froylich, D.; Corcelles, R.; Daigle, C.R.; et al. Weight loss is higher among patients who undergo body contouring procedures after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016, 12, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Sámano, M.Á.; Guerrero-Castillo, A.P.; Abarca-Arroyo, J.A.; et al. Effect of liposuction on body weight and serum concentrations of leptin, lipids, glucose, and insulin: A meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2023, 151, 402e–11e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bas, S.; Oz, K.; Akkus, A.; Sizmaz, M.; et al. Effect of reduction mammoplasty on insulin and lipid metabolism in the postoperative third month: compensatory hip enlargement. Aesthet Plast Surg 2023, 47, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannistrà, C.; Lori, E.; Arapis, K.; et al. Abdominoplasty after massive weight loss. Safety preservation fascia technique and clinical outcomes in a large single series-comparative study. Front Surg. 2024, 11, 1337948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griego, M.P.; et al. Quality of life in post-bariatric surgery patients undergoing aesthetic abdominoplasty: Our experience. Surg Chrn 2016, 21, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vater, A.M.; Fietz, J.; Schultze-Mosgau, L.E.; Lamby, P.E.; Gerauer, K.E.; Schmidt, K.; Jakubietz, R.G.; Jakubietz, M.G. Understanding the Long-Term Effects of Inverted-T-Abdominoplasty on Quality of Life: Insights from Post-Bariatric Surgery Patients. Life 2025, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan Makhtar, W.R.; Mohamad Shah, N.S.; Rusli, S.M.; et al. The impact of abdominoplasty vs non-abdominoplasty on weight loss in bariatric and non-bariatric Malaysian patients: a multicentre retrospective study. Cureus 2022, 14, e23996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopulos, N.A.; Staffler, V.; Mirceva, V.; et al. Does abdominoplasty have a positive influence on quality of life, self-esteem, and emotional stability? Plast Reconstr Surg 2012, 129, 957e–962e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.Y.; Rubin, J.P.; Thomas, V.; Dudas, J.R.; Marra, K.G.; Fernstrom, M.H. Body image and quality of life in post massive weight loss body contouring patients. Obesity 2006, 14, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).