1. Introduction

The dental pulp is vascularized and innervated connective tissue placed within the pulp chamber [

1]. Injuries from dental caries or trauma induce an inflammatory response that depends on the balance between inflammatory processes and regenerative capabilities [

2,

3,

4,

5]. To maintain pulp functionality, managing inflammation and removing extravasated fluids is essential, highlighting the critical roles of lymphatic vessels, blood vessels, and neural tissue [

6,

7].

Lymphatic vessel presence in human dental pulp remains controversial. Some studies have identified lymphatic vessels in healthy dental pulp [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], while others report their absence [

13,

14,

15]. Lymphatic vessels are vital for maintaining tissue homeostasis through the recirculation and absorption of interstitial fluid and provide defense against bacterial infections in pathological conditions[

6].

Upon activation during inflammation, sensory nerve fibers not only convey nociceptive signals but also induce neurogenic inflammation through neuropeptide release. These biomolecules trigger vasodilation, enhance vascular permeability, and facilitate immune cell recruitment and activation [

16,

17]. Additionally, pulp inflammation triggers the secretion of nerve growth factor (NGF), which plays a pivotal role in neuronal development, maintenance, and repair [

18].

Immunohistochemistry allows reliable identification of vascular and neural elements in dental pulp. The D2-40 monoclonal antibody specifically targets lymphatic endothelial cells [

19], CD31 is expressed by both blood and lymphatic vessel endothelium [

20], and PGP 9.5 specifically identifies neural elements [

21]. Despite these tools, the differential response of lymphatic vessels, blood vessels, and neural tissue to pulp inflammation has not been comprehensively characterized in a single study.

This study aimed to assess the presence and allocation of lymphatic vessels in normal and inflamed dental pulp. Determine whether pulp inflammation induces lymphangiogenesis. Evaluate changes in blood vessel density during acute and chronic pulp inflammation. Examine alterations in neural tissue characteristics during pulp inflammation. By investigating these parameters simultaneously, we seek to provide a comprehensive understanding of the neurovascular dynamics during pulpitis and identify potential targets for enhancing pulp healing and regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Reliability

Inter-examiner reliability for vessel counting demonstrated excellent agreement with an ICC of 0.92, indicating robust assessment methodology. This high level of agreement between independent examiners confirms the reliability of the vessel quantification data presented in this study.

2.2. Demographic Characteristics

Thirty-eight pulps were extirpated using a barbed broach. Fourteen pulps were diagnosed with acute pulpitis, and thirteen pulps were diagnosed with chronic pulpitis. The extirpation was performed for endodontic reasons. The remaining 11 pulp tissues were extirpated immediately after extraction of normal teeth for orthodontic reasons or impacted third molar. The extirpation approach was specifically chosen over decalcification methods to preserve tissue antigenicity and avoid false positive expression of D2-40 by lymphatics in the periodontal ligaments. All samples were submitted for histopathological evaluation using H&E stain for accurate diagnosis. Microscopical evolution was done with (leica DM750), and the image was captured by (leica ICC50 E) microscope camera. The ethics committee of Baghdad University College of Dentistry approved this study (protocol code 878). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to tissue collection and examination.

2.3. Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis of pulpitis was based on both clinical and histopathological criteria according to Folly [

22]. For acute pulpitis, clinical features included sharp pain upon thermal stimuli that subsides immediately after stimulus removal, tenderness to vertical percussion, and spontaneous severe pain, particularly nocturnal. Histologically, acute pulpitis was characterized by predominance of neutrophilic infiltration and dilated blood vessels.

Chronic pulpitis was clinically identified by dull pain upon thermal stimuli with prolonged duration after stimulus removal and large carious lesions with positive vitality tests but minimal spontaneous pain. Histologically, chronic pulpitis demonstrated chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells), fibrosis of the pulp tissue, and presence of dystrophic calcifications.

Normal pulp samples exhibited no clinical symptoms and demonstrated absence of inflammatory cell infiltrate with maintained normal tissue architecture upon histological examination.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

All specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours. Following fixation, specimens were embedded in paraffin wax, and 4 μm thick sections were prepared for immunohistochemical examination. The procedure included dewaxing and rehydration, followed by antigen retrieval using a heat-mediated method in a water bath with pH 6 for CD31 and Podoplanin and pH 9 for PGP 9.5 (Pathinsitu). After washing with immune buffer for 5 min, hydrogen peroxide blocking was performed, followed by two 5-minute washes and protein blocking. The tissue was washed twice for 5 minutes (Abcam) before applying the primary antibodies.

Three primary mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for human antigens were used: anti-CD31 (0.5 μg/ml, positive control: human tonsil), anti-PGP9.5 (2 μg/ml, positive control: human brain), and anti-podoplanin (1/10000 dilution, positive control: human placenta). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight and rinsed 4 times in buffer, followed by application of biotinylated goat anti-polyvalent (10-minute incubation, 4 washes). Streptavidin peroxidase was applied for 10 minutes, followed by 4 buffer rinses. DAB chromogen, diluted in DAB substrate according to manufacturer specifications, was applied for 7 minutes, followed by 4 rinses. Harris hematoxylin was used as a counterstain before cover slipping.

2.5. Quantification and Assessment

For vessel counting, five high-power fields (40× magnification) were systematically selected from each sample: three fields from the coronal pulp and two from the radicular pulp. All positively stained vessels were counted in each field, and the mean vessel density was calculated for each sample. To ensure reliability, all counting was performed by two independent examiners who were blinded to the sample diagnoses, with any discrepancies resolved by consensus.

For nerve tissue assessment, the PGP9.5 immunoreactivity was scored on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 represented negative staining, 1 represented less than 10% positive staining, 2 represented 10-25% positive staining, 3 represented 25-50% positive staining, and 4 represented more than 50% positive staining.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Results are presented as means, standard deviations, 95% confidence intervals, and ranges. Categorical data is presented as frequencies and percentages. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normality of the data distribution. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) (two-tailed) test was used for normally distributed data, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for abnormally distributed data to compare the biomarkers between study groups. For pairwise comparisons, Tukey's post-hoc test was applied following ANOVA, and Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction was used following Kruskal-Wallis. Pearson's correlation coefficient assessed relationships between continuous variables. A power analysis was performed to ensure adequate sample size (power = 0.8, α = 0.05). Inter-examiner reliability for vessel counting was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

A total of 38 pulp tissues were analyzed in this study, comprising 14 with acute pulpitis, 13 with chronic pulpitis, and 11 normal pulp samples. Gender distribution showed no significant differences between groups, with 42.9% male (n=6) and 57.1% female (n=8) in the acute pulpitis group, 46.2% male (n=6) and 53.8% female (n=7) in the chronic pulpitis group, and 36.4% male (n=4) and 63.6% female (n=7) in the normal pulp group. The mean age of the individuals in this study was 24.23 ± 6.8 years. No significant differences in age were observed between the study groups (p = 0.78).

3.2. Immunohistochemical Findings

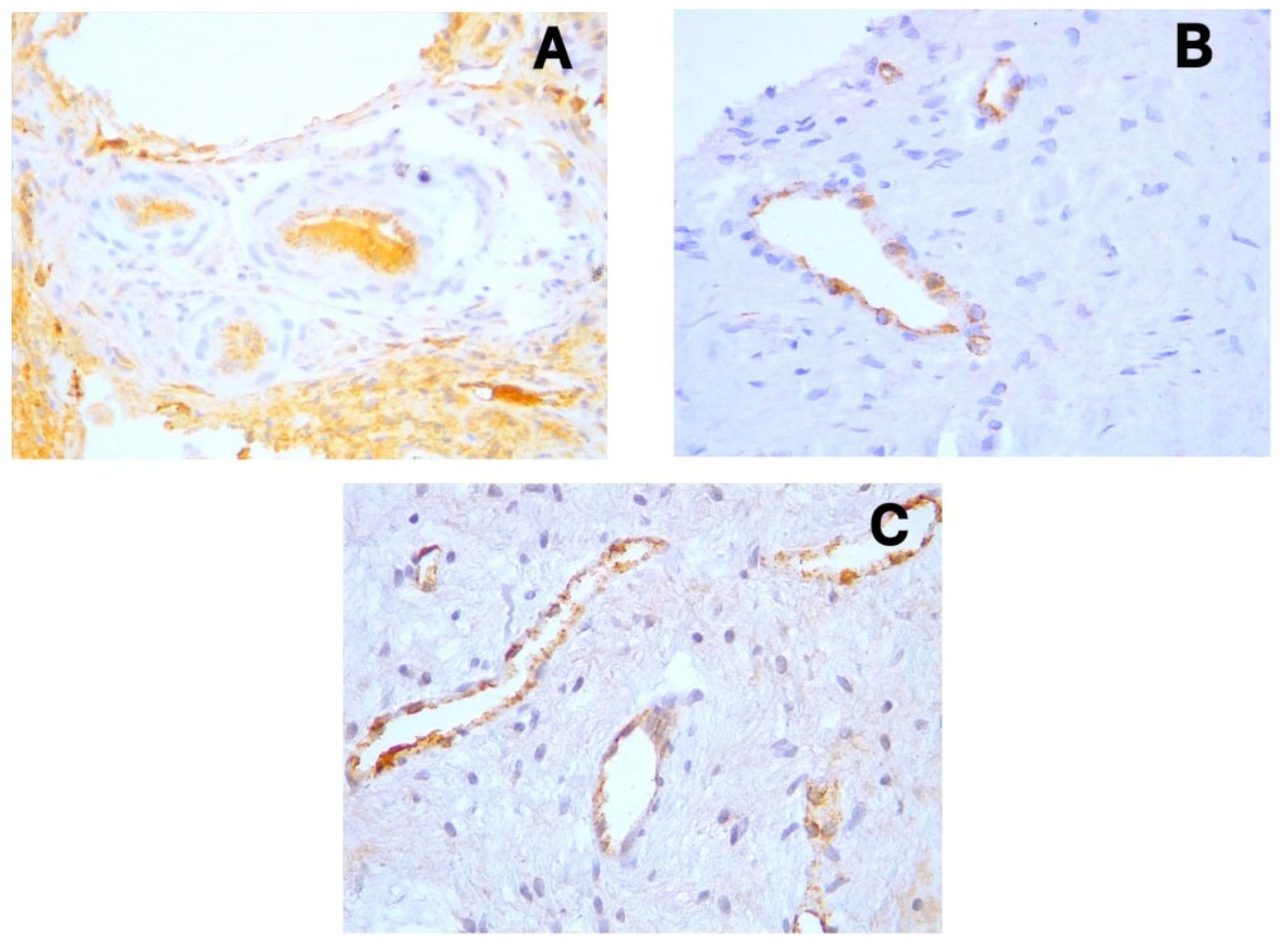

D2-40 (Podoplanin) displayed positive cytoplasmic expression in the endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels across all sample types (

Figure 1a-c). These lymphatic vessels were primarily distributed in the coronal pulp, with fewer observed in the radicular region. CD31 showed distinct cytoplasmic expression in the endothelial cells of both blood and lymphatic vessels (

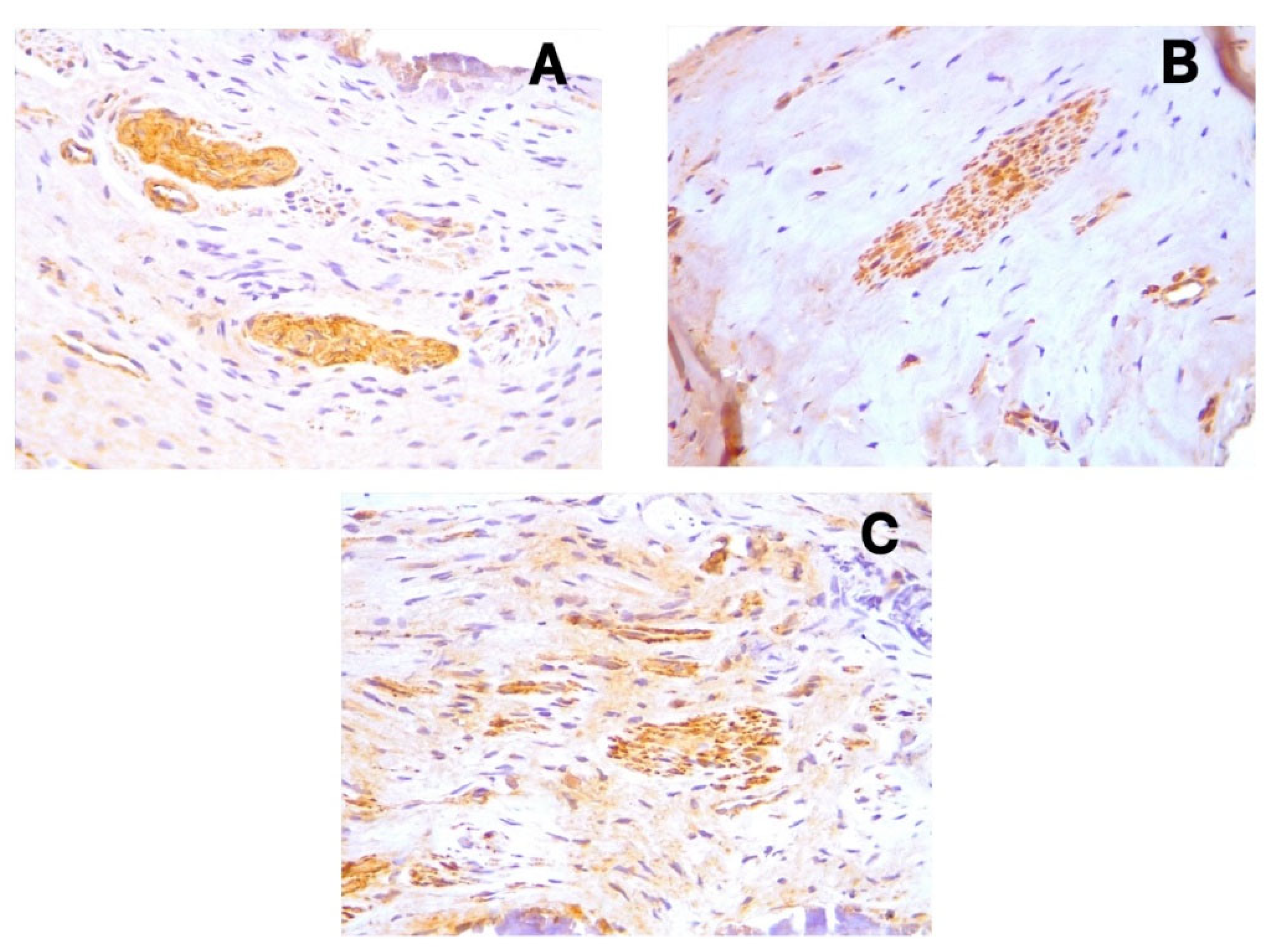

Figure 2a-c), with notably increased expression in acute pulpitis samples. PGP9.5 exhibited cytoplasmic expression in neuronal cells and pericytes surrounding blood vessel walls, with a relatively uniform distribution from coronal to radicular pulp across all groups (

Figure 3a-c).

The distribution of blood and lymphatic vessels was more pronounced in the coronal pulp than in the radicular pulp. However, during inflammation, particularly in acute pulpitis, increased angiogenesis was observed even in the radicular pulp regions. H&E staining confirmed the histopathological diagnoses of acute pulpitis (

Figure 4a), chronic pulpitis (

Figure 4b), and healthy pulp (

Figure 4c), validating the clinical classification of samples.

3.3. Vessel and Nerve Density Analysis

Acute pulpitis demonstrated a significant increase in blood vessel density as measured by CD31 immunoexpression (mean 50.3, 95% CI 43.1-57.5) compared to chronic pulpitis (mean 39.2, 95% CI 32.7-45.7) and control samples (mean 25.8, 95% CI 19.4-32.2) (p = 0.001) (

Table 1). The effect size for this difference (Cohen's d = 1.82 between acute pulpitis and control) indicates a large and clinically significant effect. In contrast, no significant differences were observed in lymphatic vessel density (D2-40 expression) or nerve tissue density (PGP9.5 expression) between the study groups (p ≥ 0.05).

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that CD31+ vessel density was significantly higher in acute pulpitis compared to both chronic pulpitis (50.3 vs. 39.2, p = 0.031) and control samples (50.3 vs. 25.8, p = 0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between chronic pulpitis and control samples (39.2 vs. 25.8, p = 0.386). This suggests that increased angiogenesis is primarily associated with acute inflammatory processes rather than chronic inflammation in dental pulp.

3.4. Correlation Analysis

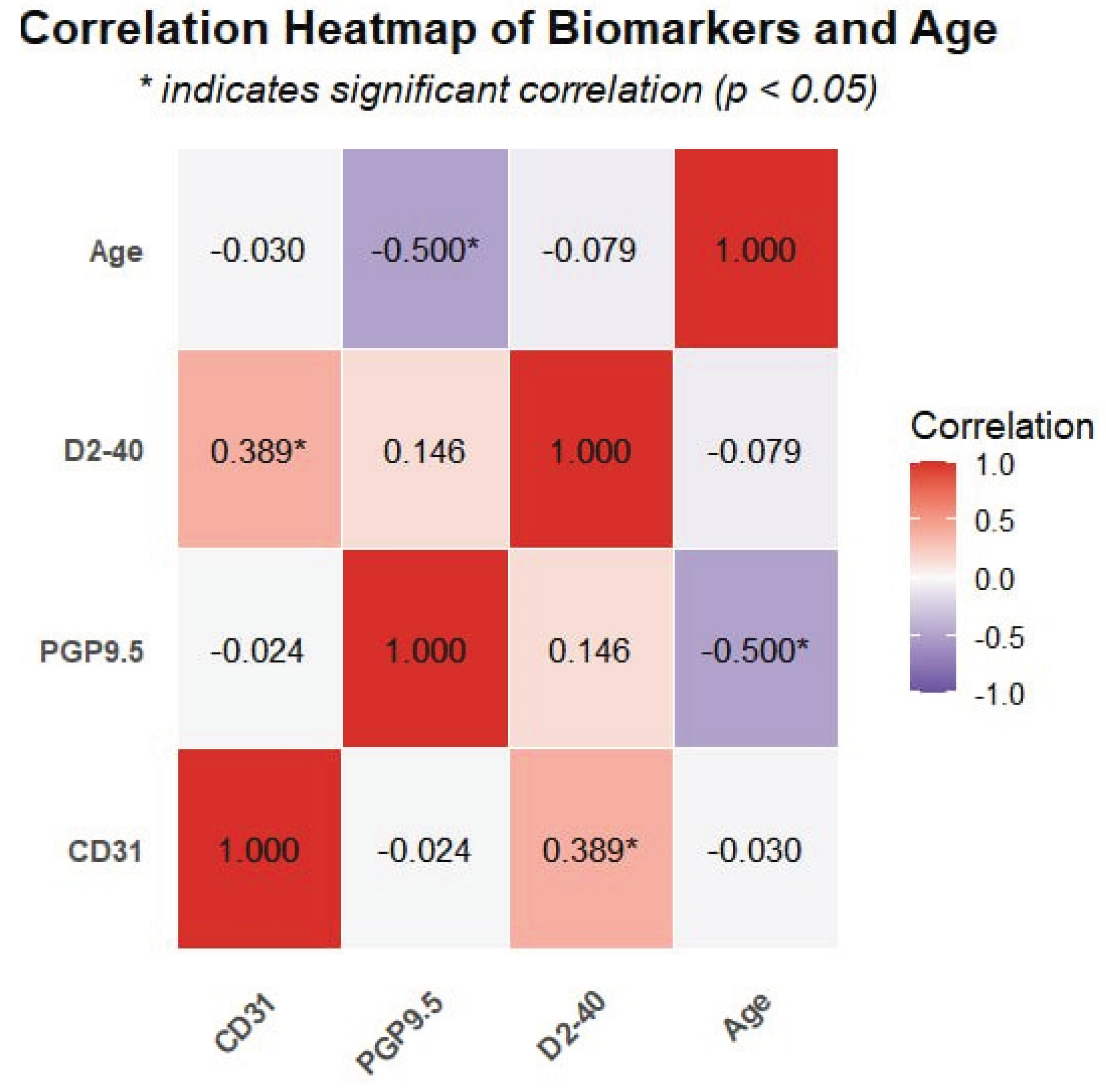

A significant positive correlation was observed between CD31 and D2-40 expression (r = 0.389, p = 0.016), suggesting coordinated development between blood and lymphatic vessels during pulpitis. However, no significant correlations were detected between PGP9.5 expression and either CD31 or D2-40 (p ≥ 0.05) (

Table 2), indicating that neural tissue regulation may follow independent pathways from vascular changes.

Notably, a significant negative correlation was detected between PGP9.5 expression and age (r = -0.5, p = 0.001), indicating a decrease in neural tissue density with advancing age. In contrast, neither CD31 nor D2-40 expression showed significant correlations with age (p ≥ 0.05), suggesting that vascular components may be less affected by aging compared to neural elements. The correlation patterns between all biomarkers and age are visually represented in the heatmap (

Figure 5), where the intensity of color indicates the strength of correlation and asterisks mark statistically significant relationships.

4. Discussion

4.1. Lymphatic Vessels in Dental Pulp

The omnipresence of lymphatic vessels in human dental pulp remains a contentious issue, particularly regarding whether inflammation in the dental pulp induces lymphangiogenesis. Our study provides important clarification on this controversial topic by demonstrating the presence of lymphatic vessels in all examined pulp samples, including normal pulp, using the highly specific D2-40 marker. This finding is significant because it resolves a fundamental question in pulp biology and contradicts several previous studies that reported the absence of lymphatics in dental pulp.

Numerous studies employing immunohistochemical techniques have affirmed lymphatic vessels presence in the dental pulp across various species [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Conversely, multiple authors have reported the absence of such vessels in the dental pulp of differing species [

13,

14,

15]. Gerli et al. assert that true lymphatic vessels are not typically present in human dental pulp but may emerge following inflammatory responses. Under physiological conditions, interstitial fluid that is not reabsorbed on the venular side would flow through 'non-endothelialized interstitial channels'[

13]. Martin et al. concluded that lymphatic vessels are absent in the dental pulp of canines, suggesting fundamental similarities in the endodontic biology of dogs and humans, in alignment with findings by Gerli et al. [

14].

Our study utilized D2-40, a marker with high specificity for lymphatic endothelium [

23], demonstrating that lymphatic vessels were present in all examined samples, including normal pulp. This finding contradicts studies reporting the absence of lymphatics in dental pulp but aligns with others that have identified these vessels[

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, the endothelium of these vessels expresses CD31, confirming the existence of an endothelial lining, given that CD31 serves as a pan-endothelial marker for both blood and lymphatic vessels [

20].

Our data indicate a moderate positive correlation between the expression of CD31 and D2-40 (r = 0.389), suggesting some degree of coordinated development between blood and lymphatic vessels. However, the density of lymphatic vessels in acute and chronic pulpitis does not significantly differ from control samples. This finding is particularly noteworthy as it suggests that, unlike angiogenesis, the lymphangiogenesis process appears to be inhibited during pulp inflammation, contradicting some studies that reported substantial lymphangiogenesis in inflamed pulps.

This impaired lymphangiogenesis may be attributable to elevated levels of nitric oxide (NO) produced during the inflammatory response. Nitric oxide interacts with superoxide (O2−) to yield toxic concentrations of peroxynitrite (OONO−)[

24]. According to Singla B. et al., low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are necessary for lymphangiogenesis, whereas excessive ROS production can inhibit lymphangiogenesis and impair lymphatic drainage[

25]. This molecular mechanism represents a potential therapeutic target for enhancing pulp healing by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment to promote lymphangiogenesis.

The inability to form new lymphatic vessels likely adversely influences the healing and regenerative capacity of the dental pulp, hindering the reabsorption of extravasated fluid and promoting its accumulation. This state predisposes the pulp to circulatory failure and potential necrosis. These findings have significant clinical implications, suggesting that therapeutic approaches aimed at enhancing lymphangiogenesis might improve pulp healing outcomes in pulpitis.

4.2. Blood Vessel Changes in Pulpitis

Our results demonstrate a striking difference in angiogenic response between acute and chronic pulpitis. While results indicate an increased presence of blood vessels in pulpitis during both acute and chronic inflammatory states, this increase is notably more pronounced in acute conditions. The mean vessel density in acute pulpitis (50.3) was nearly twice that of normal pulp (25.8), representing a large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.82). In contrast, the changes observed in chronic cases appear insignificant when compared to the normal group.

The significant angiogenesis noted in acute pulpitis can be attributed to hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia serves as a potent modulator of repair signals across various tissues, including dental pulp, as injuries—whether resulting from trauma or microbial-induced inflammation—often damage vascular structures, leading to diminished oxygen supply to the tissue. Dental pulp cells subjected to hypoxia act as the driving force behind new blood vessel formation. Furthermore, nitric oxide and other cytokines released by immune cells, fibroblasts, and odontoblasts propel angiogenesis [

26].

These findings highlight the dynamic nature of the vascular response during different stages of pulpitis and suggest that therapeutic strategies might need to be tailored differently for acute versus chronic conditions. The robust angiogenic response in acute pulpitis may represent an attempt at tissue repair that could potentially be harnessed therapeutically.

4.3. Neural Tissue Response to Inflammation

In response to inflammatory stimuli, sensory nerve fibers, besides pain signal transmission, can induce neurogenic inflammation through the secretion of neuropeptides [

27], particularly calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP). This process leads to an increase in vascular permeability, vasodilation, and angiogenesis, coupled with the recruitment and activation of immune cells [

28,

29].

The findings of this study reveal no significant variation in the density of nerve fibers (as indicated by PGP9.5 expression) in acute and chronic pulpitis compared to normal pulp. This stability in nerve density is notable since inflammation often causes damage to neural tissues. We hypothesize that dynamic regulation by nerve growth factor (NGF) facilitates neuronal differentiation) [

27], enhances nerve tissue density, and compensates for damaged nerve fibers. This indicates that neuropeptide secretion likely persists during inflammation, maintaining neurogenic inflammation in the dental pulp and engendering continuous pro-inflammatory mediator production.

Additionally, we observed a significant negative correlation between PGP9.5 expression and age (r = -0.5, p = 0.001), indicating a decrease in neural tissue density with advancing age. This finding is consistent with age-related neurodegeneration processes reported in other tissues [

30]. This age-related decline in neural elements might have implications for diagnosis and treatment outcomes in older patients with pulpitis, suggesting that age should be considered as a factor in treatment planning.

4.4. Clinical Implications and Limitations

The vascular and neural dynamics observed in our study offer important clinical insights. The imbalance between enhanced angiogenesis and impaired lymphangiogenesis likely creates an environment where inflammatory exudates accumulate, increasing intrapulpal pressure and pain. This understanding could inform targeted pain management approaches for pulpitis patients. The maintained neural tissue density during inflammation validates the continued use of pulp sensitivity testing throughout the disease process, though clinicians should consider potential reduced test reliability in older patients due to age-related neural density decline.

Therapeutically, our findings suggest that modulating the inflammatory environment to promote lymphangiogenesis while controlling excessive angiogenesis could improve pulp healing outcomes. Regenerative endodontic procedures might benefit from incorporating lymphangiogenic factors to enhance fluid drainage and reduce inflammatory pressure.

Our study has several limitations. The relatively small sample size may limit statistical power for detecting subtle differences between groups. Our immunohistochemical approach identified structures but could not assess functional lymphatic or vascular flow. The cross-sectional design prevents observation of temporal changes during disease progression, and we did not examine molecular mediators that could provide mechanistic insights into the differential vascular regulation observed.

4.5. Future Directions

Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms inhibiting lymphangiogenesis during pulp inflammation, particularly focusing on ROS and nitric oxide pathways. Investigating whether lymphangiogenic therapies improve pulp healing outcomes would be valuable for developing targeted treatments. Additional studies examining the relationship between NGF expression and nerve fiber maintenance during inflammation could identify neuroprotective strategies for pulp preservation. Longitudinal studies tracking vascular and neural changes during pulpitis progression would provide temporal insights, while more extensive investigation of age-related changes in pulp vasculature and innervation could inform age-appropriate treatment protocols.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that lymphatic vessels are present in all dental pulp samples, yet lymphangiogenesis remains impaired during pulpitis despite significant enhancement of angiogenesis in acute inflammation. This vascular imbalance—characterized by increased blood vessel formation without corresponding lymphatic development—likely contributes to inadequate clearance of inflammatory mediators and compromised healing in pulpitis. Our findings also reveal that neural tissue density remains stable during inflammation despite age-related decreases, suggesting persistent neurogenic inflammation throughout the disease process. These insights into the differential regulation of vascular and neural elements during pulpitis provide a foundation for developing targeted therapeutic approaches that promote lymphangiogenesis and improve pulp healing outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, BHA; methodology, NAA; investigation, NAA; resources, NAA; data curation, NAA; writing—original draft preparation, NAA; writing—review and editing, BHA; supervision, BHA; project administration, BHA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data collected by the researcher from which the statistical analysis obtained was saved completely and can be forward any time under your request.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghannam MG, Alameddine H, Bordoni B. Anatomy, head and neck, pulp (Tooth). 2019. https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk537112.

- Chen J, Xu H, Xia K, Cheng S, Zhang Q. Resolvin E1 accelerates pulp repair by regulating inflammation and stimulating dentin regeneration in dental pulp stem cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2021;12:1-14. [CrossRef]

- Vaseenon S, Weekate K, Srisuwan T, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S. Observation of inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dynamics, and apoptosis in dental pulp following a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis. European Endodontic Journal. 2023;8(2):148. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf MS, Khalaf BS, Abass SM. Management of trauma to the anterior segment of the maxilla: alveolar fracture and primary incisors crown and root fracture. Journal of baghdad college of dentistry. 2021;33(2):16-20. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahan ZA, Khalaf MS, Al-Assadi AH. Apexification and periapical healing of immature teeth using Mineral Trioxide Aggregate. Journal of baghdad college of dentistry. 2014;26(3):108-12. [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska K, Rybak Z, Szymonowicz M, Kuropka P, Dobrzyński M. Review on the lymphatic vessels in the dental pulp. Biology. 2021;10(12):1257. [CrossRef]

- Baru O, Nutu A, Braicu C, Cismaru CA, Berindan-Neagoe I, Buduru S, et al. Angiogenesis in regenerative dentistry: are we far enough for therapy? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(2):929. [CrossRef]

- Berggreen E, Haug SR, Mkonyi LE, Bletsa A. Characterization of the dental lymphatic system and identification of cells immunopositive to specific lymphatic markers. European journal of oral sciences. 2009;117(1):34-42. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta F, Sá A, Gomez R. Lymphangiogenesis in human dental pulp. International endodontic journal. 2003;36(12):853-6. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi S, Ambe K, Kon H, Takada S, Ohno T, Watanabe H. Immunohistochemical investigation of lymphatic vessel formation control in mouse tooth development: Lymphatic vessel-forming factors and receptors in tooth development in mice. Tissue and Cell. 2012;44(3):170-81. [CrossRef]

- Rodd HD, Boissonade FM. Immunocytochemical investigation of neurovascular relationships in human tooth pulp. Journal of anatomy. 2003;202(2):195-203. [CrossRef]

- Szeląg E, Popecki P, Puła B. Expression of CD31, podoplanin and Sox18 in dental pulp. Book ofAbstracts Katowice: 7th International ScientificConference of Medical Students and YoungDoctors. 2012:28.

- Gerli R, Secciani I, Sozio F, Rossi A, Weber E, Lorenzini G. Absence of lymphatic vessels in human dental pulp: a morphological study. European journal of oral sciences. 2010;118(2):110-7. [CrossRef]

- Martin A, Gasse H, Staszyk C. Absence of lymphatic vessels in the dog dental pulp: an immunohistochemical study. Journal of Anatomy. 2010;217(5):609-15. [CrossRef]

- Lohrberg M, Wilting J. The lymphatic vascular system of the mouse head. Cell and Tissue Research. 2016;366(3):667-77. [CrossRef]

- Mahdee AF, Alhelal AG, Whitworth J, Eastham J, Gillespie J. Evidence for complex physiological processes in the enamel organ of the rodent mandibular incisor throughout amelogenesis. Medical Journal of Babylon. 2017;14(1):68-82. https://search.emarefa.net/detail/BIM-792238.

- Kim ME, Lee JS. Advances in the Regulation of Inflammatory Mediators in Nitric Oxide Synthase: Implications for Disease Modulation and Therapeutic Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025;26(3):1204. [CrossRef]

- Mahdee A, Eastham J, Whitworth J, Gillespie J. Evidence for changing nerve growth factor signalling mechanisms during development, maturation and ageing in the rat molar pulp. International Endodontic Journal. 2019;52(2):211-22. [CrossRef]

- Amita, K. Prognostic Significance of Lymphatic Vessel Density by D2-40 Immune Marker and Mast Cell Density in Invasive Breast Cancer: A Cross Sectional Study at Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. Online Journal of Health and Allied Sciences. 2022;21(1). https://www.ojhas.org/issue81/2022-1-5.html.

- Vyberg M, Nielsen S, Bzorek M, Røge R. External quality assessments of CD31 immunoassays-The NordiQC experience. Vascular Cell. 2020;12(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman A-qG, Endytiastuti E, Ardhani R, Sudarso ISR, Pidhatika B, Fauzi MB, et al. Evaluating the Efficacy of Gelatin-Chitosan-Tetraethyl Orthosilicate Calcium Hydroxide Composite as a Dental Pulp Medicament on COX-2, PGP 9.5, TNF-α Expression and Neutrophil number. F1000Research. 2025;13:1258. [CrossRef]

- Odell, EW. Cawson's Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine - E-Book: Cawson's Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine - E-Book: Elsevier; 2024. https://shortlink.uk/Zcyi+.

- Qi LW, Xie YF, Wang WN, Liu J, Yang KG, Chen K, et al. High microvessel and lymphatic vessel density predict poor prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18080. [CrossRef]

- Galler KM, Weber M, Korkmaz Y, Widbiller M, Feuerer M. Inflammatory response mechanisms of the dentine–pulp complex and the periapical tissues. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(3):1480. [CrossRef]

- Singla B, Aithabathula RV, Kiran S, Kapil S, Kumar S, Singh UP. Reactive oxygen species in regulating lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic function. Cells. 2022;11(11):1750. [CrossRef]

- Colombo JS, Jia S, D'Souza RN. Modeling hypoxia induced factors to treat pulpal inflammation and drive regeneration. Journal of Endodontics. 2020;46(9):S19-S25. [CrossRef]

- Zhan C, Huang M, Yang X, Hou J. Dental nerves: a neglected mediator of pulpitis. International Endodontic Journal. 2021;54(1):85-99. [CrossRef]

- Diogenes, A. Trigeminal sensory neurons and pulp regeneration. Journal of endodontics. 2020;46(9):S71-S80. [CrossRef]

- Caviedes-Bucheli J, Lopez-Moncayo LF, Muñoz-Alvear HD, Gomez-Sosa JF, Diaz-Barrera LE, Curtidor H, et al. Expression of substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and vascular endothelial growth factor in human dental pulp under different clinical stimuli. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H. Aging and senescence of dental pulp and hard tissues of the tooth. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2020;8:605996. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).