1. Introduction

The dental pulp is a specialized connective tissue encased within hard dentin, making it particularly vulnerable to injury from mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli during restorative dental procedures. This confined condition of the pulp mean that even slight inflammatory incidences can quickly intensify, jeopardizing the pulp's vitality and resulting in irreversible injury [

1,

2].

Cavity preparation is one of the most prevalent iatrogenic factors affecting the pulp. The extent of mechanical damage during cavity preparation—specifically, the depth of the preparation to the pulp chamber—significantly influences the intensity of the inflammatory reaction. Conservative procedures that retain a significant amount of dentin may preserve the pulp by reducing the transmission of noxious stimuli. Conversely, extensive preparations, particularly those leading to pulp exposure, can trigger severe inflammatory responses that render the pulp susceptible to necrosis [

3,

4].

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and nitric oxide (NO) are primary inflammatory mediators implicated in the initial stages of pulpal inflammation. PGE2, synthesized through the cyclooxygenase pathway, is recognized for its strong vasodilatory and nociceptive properties, increasing vascular permeability and sensitizing nociceptors to pain stimuli. Nitric oxide, predominantly produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in inflamed tissues, also has a role in vascular control and the recruitment of immune cells. Both molecules are promptly increased after tissue injury and are regarded as key contributors to the development of pulpitis [

5,

6].

While the functions of PGE2 and NO in pulpal inflammation have been thoroughly elucidated, there is a scarcity of data concerning the impact of varying degrees of mechanical injury, namely moderate versus deep cavity preparations, on their release dynamics. Understanding these patterns is essential for enhancing restorative techniques and reducing adverse pulpal outcomes [

7,

8].

The present study aims to evaluate the effects of moderate and deep cavity preparations (with and without pulp exposure) on the release of PGE2 and NO within the pulp tissue of rat mandibular incisors, measured at 3 and 9 hours post-injury intervals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

The animal experiment within this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Baghdad with project no. (902524) on (22-2-2024). 40 male Wistar rats (6-8 w) were selected in this study. The experimental model was a split-mouth design by preparing cavities with different depths on the mandibular left incisors while leaving the right incisors without cavities as controls. Animals were divided into two main groups (n=20) according to the cavity depth into; moderate depth cavities without pulp exposure and deep cavities with pulp exposure. These two groups were further subdivided according to time period (n=10) into early 3hr and delay 9hr groups [

8].

2.2. Sample Preparation

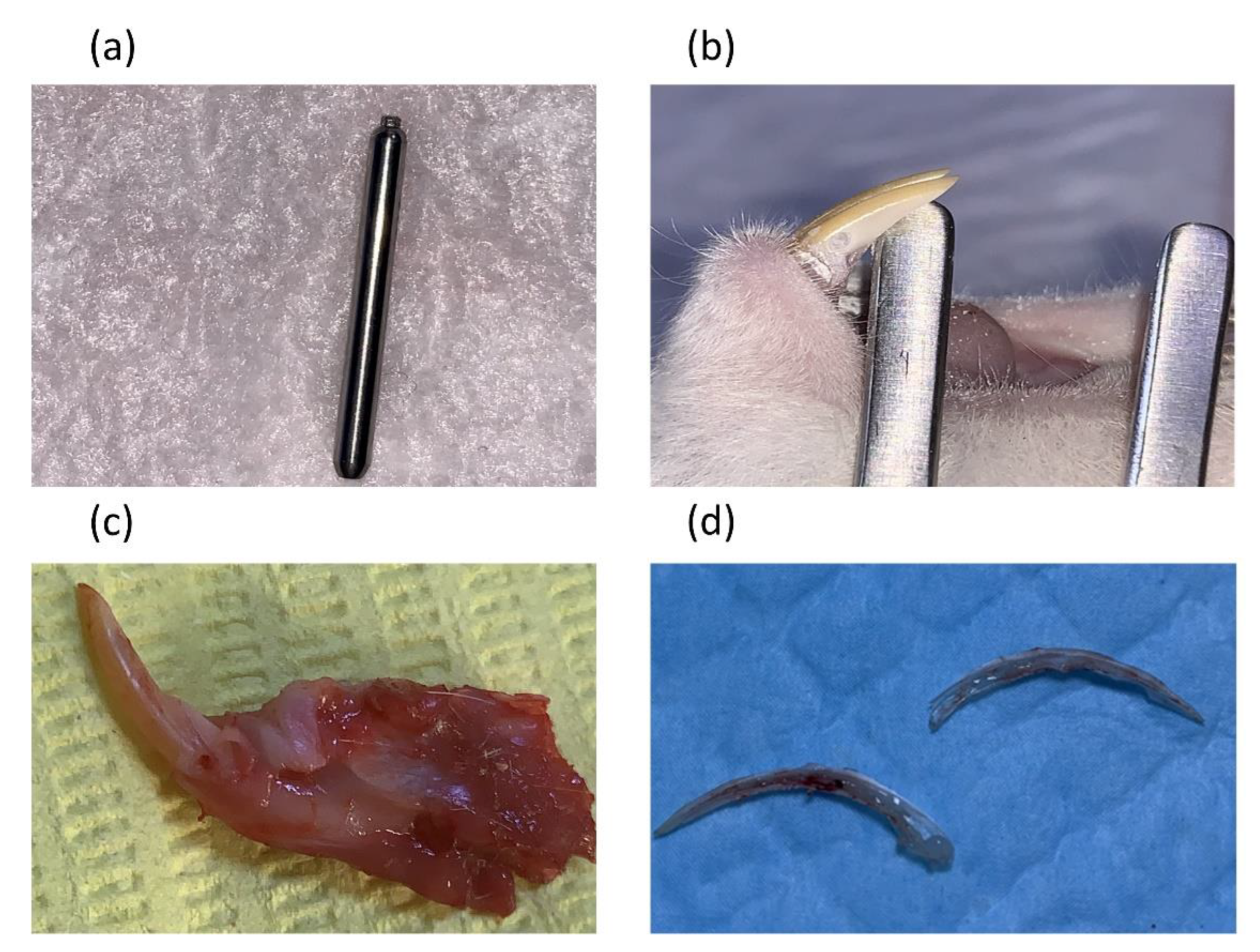

the levels of PGE2 and NO were measured from the pulp tissue after animal euthanasia and pulp tissue extractions. The rats were first anaesthetized by administering a combination of 0.1 ml ketamine and 0.2 ml xylazine intramuscularly. Depth cut diamond burs Komet® PrepMarker® instrument (DM05) were used to prepare a reproducible cavity of a controlled depth and dimensions that induce pulp exposure in the most cervical part of the mandibular incisor after reflecting the gingiva using a sterile scalpel blade. Bleeding at the exposure site was controlled by pressing a sterile saline soaked cotton pellet over the exposure for 1–2 min

Figure 1. Then the cavity was sealed using glass ionomer filling cement (Promedica Medifil) without any capping material. The cavities without pulp exposure group were made on the distal side of the mandibular incisor teeth using the same Komet® PrepMarker® instrument (DM05) diamond bur [

9]. After each period (3 and 9hr), animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation before surgical extraction of the mandibular incisors. Each tooth was sectioned longitudinally, under a magnifying binocular loupes (Jucheng, China), by making grooves on the dentin without exposing the pulp, using a cutting disc under water cooling. The teeth were then separated into two halves by using surgical blades before extracting pulp tissues by a sterile tweezer (

Figure 1 image d). Pulp homogenate was prepared following a procedure by Ellen Berggreen [

7]. Each pulp was weighted before being minced, and soaked into 0.5ml of phosphate buffered saline in an Eppendorf tubes to be stored overnight at 4◦C. Samples were then centrifuged (Eppendorff 5417 R, Germany) at a speed of 5000rpm for 20min and the supernatant was collected for ELISA testing. PGE2 (Biont, China) and NO (Biont, China) ELISA kits were used to detect the levels of these two biomarkers according to their manufacturer’s instructions at a wavelength of 450 ± 10nm.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Shapiro-Wilk test has been used to determine the normality of the results at p≤0.05. Multi-variance analysis was used to identify the effect of tooth (control vs. cavity), depth of cavity (without vs. with exposure) and time (3hr vs. 9hr) on levels of PGE2 and NO. Also, Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare levels of these markers at p≤0.05 between controls (n=20) and both cavity type groups (n=10 for each) within each time-period. In addition, Spearman correlation assay was used to identify the relation between the two biomarkers (PGE2 and NO).

3. Results

The data collected were not normally distributed as compared in Shapiro Wilk test (p˃0.05), therefore, all concentration measurements for PEG2 and NO were presented by medians and interquartile range

Table 1. It is obvious that the medians for both PGE2 and NO concentrations are higher within cavity groups in comparison to their controls. Also, medians for these biomarkers are higher in groups of cavities without pulp exposures than those with pulp exposures. While concentrations of PGE2 and NO after 9hr were slightly decreased compared with their values after 3hr for all groups except for the NO concentration in cavity with pulp exposure group where the concentrations were slightly higher.

The multivariate mixed model analysis shows that both tooth type (control vs. cavity) and cavity depth (without vs. with pulp exposure) have statistically significant differences (p≤0.001) on both PGE2 and NO concentrations. While, the time-periods show no statistical significant difference (p˃0.05)

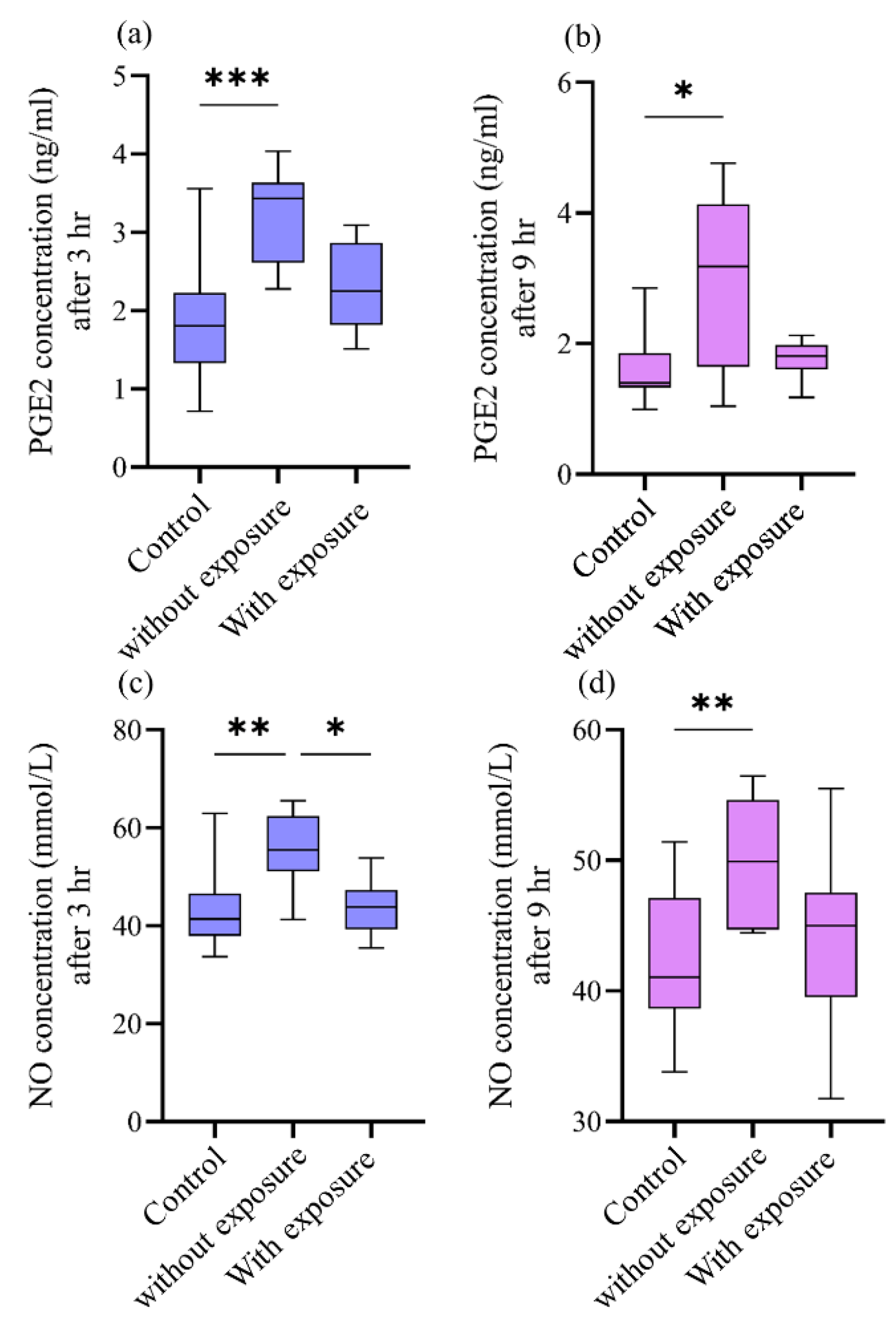

Table 2. To identify the significant differences in concentrations of PGE2 and NO between controls and the two types cavity groups Kruskal Wallis test was used. This test showed that there are statistically significant diffrences (p≤0.05) between all tested groups at the two time-periods. Multiple comparison tests for PGE2 and NO at each time-period are presented in

Figure 2. For PGE2 concentrations, only cavities without pulp groups showed the statisitical significant differences in comparison to their controls at both 3hr (p≤0.001) and 9hr (p≤0.05)

Figure 2 image (a) and (b) respectively. In the same way, NO concentrations also show statistical significant differences between cavities without pulp exposure groups in comparison to their controls at 3hr time-interval (p≤0.01)

Figure 2 image (c) and (d). Also, a statistical significant difference (p≤0.05) is present between groups without and with pulp exposure at 3hr time-period only. Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between PGE2 and NO concentrations at both time points. At 3 hours, a moderate correlation was observed (r = 0.507, p = 0.02), which became stronger at 9 hours (r = 0.602, p = 0.005), indicating that the increase in one mediator tends to be associated with a concurrent rise in the other

Table 3.

4. Discussion

This study identified that cavity causes higher levels of two pathways (PGE2 and NO) within the dental pulp as an early inflammatory response. This effect is apparent to be dependent on the depth of the cavity rather than the time of observation (3 and 9 hr). Both PGE2 and NO pathways are believed to play important roles in the regulation of normal physiological processes, inflammation and pathogenesis of pulp diseases [

10]. A deeper understanding of these processes can assist clinical procedures by suggesting the best therapeutic protocols, particularly for vital pulp therapy, to optimize the treatment outcomes. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study that directly assesses the impact of cavity preparation, and its depth on PGE2 and NO release from dental pulp homogenates.

Prostaglandin E2 is recognized as a crucial modulator of pulp inflammation by increasing vascular permeability, facilitating vasodilation, and sensitizing nociceptors, which results in pain perception [

2]. PGE2 is also recognized for sensitizing peripheral nociceptors, thereby reducing the pain threshold and facilitating the onset of hyperalgesia in inflamed pulp tissue [

4]. Nonetheless, high or sustained release of PGE2 may lead to chronic inflammation and pulpal necrosis [

5]. The increased levels of PGE2 observed in this study after cavity preparation further substantiate its essential role in triggering the inflammatory response after mechanical injury. Likewise, nitric oxide serves as a multifunctional signaling molecule that facilitates vasodilation, recruits inflammatory cells, and modulates immunological responses. NO also serves a dual function in the advancement of pulp inflammation. In the initial inflammatory phase (0–3 hours), NO exerts protective effects through many mechanisms: it promotes vasodilation by activating soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), resulting in elevated intracellular cyclic GMP, which facilitates relaxing of the pulp microvasculature and enhances blood perfusion. Furthermore, NO enhances the innate immune system by generating peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻) upon reaction with superoxide (O₂), demonstrating antibacterial properties. It also temporarily inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, hence regulating excessive inflammation [

11]. This study found that non-exposure cavities had increased NO levels at 3 hours (55.45 µmol/L), in contrast to 41.38 µmol/L in controls, suggesting vasodilation-mediated regulation of the acute inflammatory response.

Conversely, in the late inflammatory phase (>6 hours), the function of NO becomes increasingly destructive. Prolonged nitric oxide levels interact with O₂ to generate elevated concentrations of peroxynitrite, which can initiate oxidative stress reactions such as lipid peroxidation, damage to odontoblast membranes, and DNA strand breaks resulting in fibroblast apoptosis. Nitric oxide also augments TRPV1 channel activity, facilitating pain sensitization. High NO levels act as a compensatory mechanism by suppressing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression over time, which may result in a reduction of NO production [

12]. This trend is supported by the mild rise of 8.2% detected in exposed cavities at 9 hours compared to 3 hours.

Clinically, early NO elevation correlates with positive results in reversible pulpitis, whereas sustained increase in the later phase may indicate irreversible damage and necrosis, frequently necessitating root canal treatment. Targeted manipulation of NO pathways may provide therapeutic advantages: early administration of L-NAME (a NOS inhibitor) could mitigate excessive vasodilation, while antioxidants such N-acetylcysteine (NAC) may counteract surplus peroxynitrite in the latter stages [

13,

14].

The presence and regulation of these mediators dictate both the severity of the inflammatory response and the potential for pulp healing or irreversible injury. Understanding their behavior in reaction to various injury types (with or without pulp exposure) might assist clinicians in choosing restorative methods that reduce adverse inflammatory reactions and facilitate healing, while conserving pulp vitality wherever feasible.

The findings of this study are in agreement with the literature [

15,

16,

17] were the PGE2 and NO secretion increase following trauma or injury to the pulp. Conversely, this study revealed paradigm-shifting observation regarding pulp inflammatory dynamics. The 'Non-Exposure Paradox' demonstrated that cavities stopping short of pulp exposure generated 96.3% higher PGE2 and 34.1% higher NO compared to controls at 3h (p<0.001), challenging the classical assumption that greater injury elicits stronger inflammation [

18].

Furthermore, the significant difference observed between the two cavity types at 3 hours but not at 9 hours suggests that cavity depth plays a more prominent role in modulating the immediate inflammatory response rather than the delayed one. The more pronounced mediator release at the early stage could be attributed to the initial mechanical stimulus and subsequent activation of COX-2 and iNOS pathways [

15,

16].

As mentioned earlier, the current results showed that cavities without pulp exposure have higher median concentrations of both PGE2 and NO compared to cavities with pulp exposure. This may indicate the impairment of cellular components generating PGE2 and NO, or a mere cessation of the signal due to tissue necrosis [

3]. The preservation of pulp structure seems to facilitate a regulated inflammatory response conducive to healing, while exposure may lead to significant cell death and disruption of mediator synthesis. This conclusion is consistent with Bletsa et al., who showed that intact pulp tissue exhibits more active inflammatory signaling than highly injured pulp [

7].

This study additionally noted that the levels of PGE2 and NO did not exhibit significant differences between the two time intervals (3 hours versus 9 hours). This suggests that the highest production of inflammatory mediators commenced shortly after injury and remains consistent during the initial hours, supporting previous research indicating that PGE2 and NO are among the earliest molecules upregulated in the acute inflammatory phase [

8].This sustained increase may facilitate vasodilation, immune cell recruitment, and local tissue perfusion, thereby promoting a regulated inflammatory environment. Nonetheless, the extended presence of such mediators, particularly beyond the acute phase, may facilitate persistent nociceptor sensitization and pain perception. It is commonly believed that these levels diminish as healing progresses, assuming the injury does not aggravate or get infected; otherwise, their persistence may lead to chronic inflammation and pulpal degeneration [

19].

Furthermore, it appears that these mediators are co-regulated during the early inflammatory response because of the positive correlation between PGE2 and NO at both 3 and 9 hours. Their simultaneous rise suggests a common upstream signaling pathway, which may be triggered by NF-κB activation or the production of cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β. This interaction may increase pain sensitivity and the local inflammatory response, but it may also help coordinate the healing process by boosting immune and vascular cell activity. Understanding this relationship may help clinicians develop treatment plans that target simultaneous modulation of both mediators to successfully manage pain and inflammation [

15].

Whilst the tooth model used in the current study was a rat incisor with a continuous growth pattern, its size and position within the rat's mouth make it a well-established model for studying pulp tissue [

20]. However, further assessment in teeth with limited growth is required for better clinical application and to avoid any anatomical and physiological variations [

21]. Also, this study concentrated on the early post-injury intervals (3 and 9hr), because levels of the selected markers are importantly acting within this period of inflammation [

8]. But understanding their levels further to this stage is also recommended. In addition, the testing procedure of ELISA yields quantitative data regarding mediator levels, it cannot provide spatial localization of their expression within the pulp tissue [

22]. Therefore, specific identification for the pulp cells responsible for the secretion of these markers should be considered.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasises the critical influence of cavity depth on the inflammatory response of dental pulp, as indicated by PGE2 and NO levels in a rat model. Three principal conclusions were derived from the analysis.

Firstly, cavities that maintained pulp integrity resulted in markedly elevated levels of inflammatory mediators, with a 96% rise in PGE2 and a 34% increase in NO compared to controls (p < 0.001), suggesting that a structurally intact pulp generates a more coordinated and vigorous immune response. This observation defies the common belief that increased tissue damage results in stronger inflammation, leading to what may be referred to as the 'Pulp Integrity Paradox.'

Secondly, direct pulp exposure resulted in a 35% decrease in PGE2 release compared to non-exposed cavities (p < 0.05), possibly attributable to necrosis-induced impairment of odontoblast function and the disintegration of paracrine signalling networks. This indicates that overt damage may hinder, rather than enhance, mediator production.

Third, temporal analysis demonstrated dynamic NO behavior: an initial peak at 3 hours (55.45 µmol/L), succeeded by a relative decrease at 9 hours. This biphasic pattern may indicate a transition from protective vasodilation in the initial phase—potentially facilitated by eNOS—to a cytotoxic condition characterised by peroxynitrite and iNOS pathways in the later phase. These findings provide insight into possible therapeutic opportunities for clinical intervention.

Clinically, these findings support the use of less invasive restorative procedures, including selective caries removal, to maintain the vitality of the pulp and any remaining dentin.

Data Availability Statement:

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; methodology, H.R.F. and A.F.M..; software H.R.F. and A.F.M..; validation, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; formal analysis, H.R.F. and A.F.M. investigation, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; resources, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; data curation H.R.F. and A.F.M.; writing—original draft preparation H.R.F. and A.F.M.,; writing—review and editing, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; visualization, H.R.F. and A.F.M.; supervision H.R.F. and A.F.M.; project administration, H.R.F. and A.F.M..; funding acquisition, H.R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, The research ethics committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad, reviewed and approved the research project (protocol code 902524, ref. number 902 on 22/2/2024).”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.”.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Kim, S. , "Microcirculation of the dental pulp in health and disease," (in eng), J Endod, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 465-71, Nov 1985. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Trowbridge, H.O.; Dorscher-Kim, J.E. , "The influence of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) on blood flow in the dog pulp," (in eng), J Dent Res, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 682-5, May 1986. [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.E.; Smith, A.J.; Windsor, L.J.; Mjör, I.A. , "Remaining dentine thickness and human pulp responses," (in eng), Int Endod J, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 33-43, Jan 2003. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.R. Dental iatrogenesis. Int Dent J 1994, 44, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodis, H.E.; Bowles, W.R.; Hargreaves, K.M. , "Prostaglandin E2 enhances bradykinin-evoked iCGRP release in bovine dental pulp," (in eng), J Dent Res, vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 1604-7, Aug 2000. [CrossRef]

- Mollace, V.; Muscoli, C.; Masini, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Salvemini, D. , "Modulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis by nitric oxide and nitric oxide donors," (in eng), Pharmacol Rev, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 217-52, Jun 2005. [CrossRef]

- Bletsa, A.; Berggreen, E.; Fristad, I.; Tenstad, O.; Wiig, H. , "Cytokine signalling in rat pulp interstitial fluid and transcapillary fluid exchange during lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation," (in eng), J Physiol, vol. 573, no. Pt 1, pp. 225-36, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, N.; Nakano-Kawanishi, H.; Suzuki, N.; Takagi, M.; Suda, H. , "Effect of NOS inhibitor on cytokine and COX2 expression in rat pulpitis," (in eng), J Dent Res, vol. 84, no. 8, pp. 762-7, Aug 2005. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mahdee, A.; Mohmmed, S. , "Cavity preparation model in rat maxillary first molars: A pilot study," Journal of Baghdad College of Dentistry, vol. 35, pp. 1-9, 12/15 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.M.; et al. , "Dual involvements of cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase expressions in ketamine-induced ulcerative cystitis in rat bladder," (in eng), Neurourol Urodyn, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1137-43, Nov 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mollace, V.; Muscoli, C.; Masini, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Salvemini, D. Modulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis by nitric oxide and nitric oxide donors. Pharmacological reviews 2005, 57, 217–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diogenes, A.; Henry, M.; Teixeira, F.; Hargreaves, K. , "An update on clinical regenerative endodontics," Endodontic Topics, vol. 28, 03/01 2013. [CrossRef]

- Di Spirito, F.; Scelza, G.; Fornara, R.; Giordano, F.; Rosa, D.; Amato, A. , "Post-Operative Endodontic Pain Management: An Overview of Systematic Reviews on Post-Operatively Administered Oral Medications and Integrated Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations," (in eng), Healthcare (Basel), vol. 10, no. 5, Apr 19 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nixdorf, D.R.; Law, A.S.; John, M.T.; Sobieh, R.M.; Kohli, R.; Nguyen, R.H. , "Differential diagnoses for persistent pain after root canal treatment: a study in the National Dental Practice-based Research Network," (in eng), J Endod, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 457-63, Apr 2015. [CrossRef]

- Petrini, M.; et al. Prostaglandin E2 to diagnose between reversible and irreversible pulpitis," International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2012, 25, 157–163. 25.

- Coleman, J.W. , "Nitric oxide in immunity and inflammation," (in eng), Int Immunopharmacol, vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 1397-406, Aug 2001. [CrossRef]

- Alhelal, A.; Mahdee, A.; Eastham, J.; Whitworth, J.; Gillespie, J. Complexity of odontoblast and subodontoblast cell layers in rat incisor. RRJDS 2016, 4, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge, H.O. , "Pathogenesis of pulpitis resulting from dental caries," (in eng), J Endod, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 52-60, Feb 1981. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, F. Pulpal response to restorative procedures and materials. Curr Opin Dent 1992, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mahdee, A.; Eastham, J.; Whitworth, J.M.; Gillespie, J.I. , "Evidence for programmed odontoblast process retraction after dentine exposure in the rat incisor," Archives of Oral Biology, vol. 85, pp. 130-141, 2018/01/01/ 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mahdee, A.; Eastham, J.; Whitworth, J.; Gillespie, J. Evidence for changing nerve growth factor signalling mechanisms during development, maturation and ageing in the rat molar pulp. International Endodontic Journal 2019, 52, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhelal, A.; Mahdee, A.; Gillespie, J.; Whitworth, J.; Eastham, J. Evidence for nitric oxide and prostaglandin signalling in the regulation of odontoblast function in identified regions of the rodent mandibular incisor. International Endodontic Journal 2016, 49, 39. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).